Abstract

The nocebo effect is defined as the incitement or the worsening of symptoms induced by any negative attitude from non-pharmacological therapeutic intervention, sham, or active therapies. When a patient anticipates a negative effect associated with an intervention, medication or change in medication, they may then experience either an increase in this effect or experience it de novo. Although less is known about the nocebo effect compared with the placebo effect, widespread interest in the nocebo effect observed with statin therapy and a literature review highlighting the nocebo effect across at least ten different disease areas strongly suggests this is a common phenomenon. This effect has also recently been shown to play a role when introducing a medication or changing an established medication, for example, when switching patients from a reference biologic to a biosimilar. Given the important role biosimilars play in providing cost-effective alternatives to reference biologics, increasing physician treatment options and patient access to effective biologic treatment, it is important that we understand this phenomenon and aim to reduce this effect when possible. In this paper, we propose three key strategies to help mitigate the nocebo effect in clinical practice when switching patients from reference biologic to biosimilar: positive framing, increasing patient and healthcare professionals’ understanding of biosimilars and utilising a managed switching programme.

Similar content being viewed by others

The nocebo effect is a non-pharmacological effect causing a negative subjective outcome on treatment, which cannot be objectivised. It is a known but often disregarded phenomenon, impacting patient outcomes across different therapy areas. |

Specific areas of nocebo-related research focusing on reference biologic to biosimilar biologic switching has rekindled interest in the nocebo effect and its clinical implications. |

A lack of knowledge regarding biosimilars is causing reticence to switch; improving communication strategies when transitioning patients to a biosimilar may improve clinical outcomes and discontinuation rates. A coherent approach across the full healthcare team is required to realise the cost-saving potential of biosimilars. |

1 Introduction

“But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought.” George Orwell [1].

The significant power of the physician–patient relationship has been documented for centuries. The power of words within that relationship is crucial. Words have the power to harm or to heal, and how one word is said, the emphasis placed on it, and both verbal and non-verbal cues are important. The same may be said of the relationship between the physician and the patient, previous patient experiences, preconceptions, and even the setting of the conversation and health state of the patient at the time. Each of these factors contribute to the understanding that a patient has following a consultation and their expectations of the medication that they receive, both of which can influence whether a nocebo effect is likely to occur [2].

2 What is the Nocebo Effect?

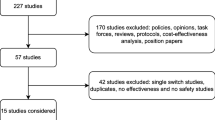

As a result of physician–patient communication and patient treatment expectations, two clinical phenomena can be described: the placebo effect and the nocebo effect [2, 3]. The placebo effect is a well-accepted phenomenon and has been widely studied [4]; it can provide clear clinical benefits, such as pain management, as was reported in 1978 [5]. The placebo effect conveys positive beliefs and beneficial outcomes from a positive communication about a sham treatment or medication that the patient is/will be receiving [2]. The nocebo effect is defined as the incitement or the worsening of symptoms induced by any negative attitude from non-pharmacological therapeutic intervention, sham, or active therapies (Fig. 1) [2, 3]. When a patient anticipates a negative effect associated with an intervention, medication or change in medication, they may then experience either an increase in this effect or experience it de novo [2, 3].

Although less is known about the nocebo effect than the placebo effect, a recent literature review (Table 1) highlights the nocebo effect across at least ten disease areas, strongly suggesting this is not a ‘new’ phenomenon [3]. Nocebo effects can play an important role when introducing a medication or changing an established medication. There have been interesting investigations concerning treatment of pain, epilepsy, and itch showing the influence of physician–patient communication [6,7,8]. Gagne et al. in 2010 were the first to document that anti-epileptic drug prescription refilling may be associated with an elevated risk of seizure-related events, indicating a pattern independent of any transitioning issues [7]. Additionally, the introduction of generic medicines brought new insights concerning the influence of negative expectations on the rate of adverse events (AEs) [9]. Kesselheim et al. in 2010 reported how observational studies have identified negative trends attributed to changes in epilepsy seizure control after transition to generic drugs [10]. In contrast, evidence from available randomised controlled trials was unable to provide an association between loss of seizure control and generic substitution [10]. Findings from the observational studies may be due to unnecessary concerns from patients or healthcare professionals (HCPs) about the effectiveness of generic anti-epileptic drugs after recent transition [10]. Today we face a similar situation with biosimilars.

Biosimilars provide cost-effective alternatives to reference biologics, leading to an increase in physician treatment options and patient access to effective biologic treatment. However, considering a switch can be daunting [19], and it is the responsibility of the physician to ensure patients are fully confident in understanding the benefits and risks, so that they can help their patients make informed choices without bias [19]. Where confidence in biosimilars is not built through traditional clinical training, knowledge of and access to high-quality data, and subsequently unsuccessfully communicated to patients, the nocebo effect is a real risk with possible negative implications (Table 2) [20].

3 Nocebo Effect when Switching to Biosimilars

The NOR-SWITCH study, a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority, phase IV study, was conducted in adult patients with axial spondyloarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, or psoriasis. Patients with informed consent were randomised to either continue originator infliximab (IFX) or to transition to biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) [21]. This trial demonstrated that switching from IFX to CT-P13 was non-inferior to continued treatment with IFX [21]. However, discordance in patient and physician outcome reporting was observed, which is a phenomenon previously reported [22]. Using patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures such as patient global assessment—one of the most widely reported PROs in RA—allows a more holistic assessment of disease and provides the patients’ perspective on aspects of their condition [23]. Figure 2 highlights disease experience also worsened under reference treatment, stressing the necessity for adequate controls when interpreting results regarding the response to change in treatment in single-arm studies.

Global assessment of disease activity (NOR-SWITCH trial) [21]. Patients with informed consent were randomised to either continue IFX or to transition to CT-P13. CT-P13 biosimilar infliximab, IFX originator infliximab

Although data from controlled blinded trials have shown biosimilars used for treatment of autoimmune diseases to be equivalent to their reference biologic, data on open-label transitioning to biosimilars are scarce. BIO-SPAN, the abstract of which was presented at EULAR 2017, and BIO-SWITCH are two such observational studies [24, 25]. These two studies (BIO-SWITCH, from IFX to CT-P13, and BIO-SPAN, from reference etanercept [ETN] to biosimilar etanercept [SB4]) were conducted in patients with rheumatic disease using different communication strategies to assess how an effective communication strategy may impact on reducing the nocebo effect [24, 25]. In patients transitioning from ETN to SB4, communication around transitioning was enhanced with additional information on the lower costs of treatment and data regarding potentially fewer injection-site reactions. During 84 person-years of follow-up, 47 patients discontinued CT-P13 (56/100 person-years; 26% due to inefficacy, 74% due to AEs). In contrast, 36 patients discontinued SB4 during 230 person-years of follow-up (16/100 person-years; 53% due to inefficacy, 42% due to AEs and 5% due to remission) [24,25,26], demonstrating that improved communication resulted in much higher acceptance and persistence rates in those switching from a reference product to a biosimilar [24,25,26]. These data are also supported by five recent studies in which authors suggest a nocebo influence has occurred when patients were switched from reference biologics to biosimilars (Table 3).

In these examples, where effectiveness and safety were generally maintained, the authors hint to the nocebo effect to explain some of the observations where patient expectations may have affected the outcome, and not the pharmacological properties of the agents involved. Considering the widespread influence the nocebo effect can have, interest in how to negate this effect to improve clinical outcomes and reduce cost burdens is increasing [2, 3, 32].

4 Overcoming the Nocebo Effect: Triggers and Practical Guidance for Clinical Practice

It is clear from the literature that there are three key triggers for the nocebo effect, which may offer possible solutions to overcoming it in clinical practice in the future:

-

1.

Only one occasion of negative information can induce long-lasting negative clinical effects [33]. The process of ensuring informed consent before treatment can always be challenging, not only when deciding to transition from reference biologics to biosimilars. By definition the probability of an AE should be similar whether the patient remains on the reference biologic or switches to a biosimilar; informed consent of both agents would have similar positive aspects and negative side effects, and the transition should be communicated as such. Shared decision making, therefore, is critical in avoiding triggering a nocebo effect. Thus, an interesting ethical dilemma is raised about whether informing without qualification can compromise the Hippocratic Oath. To deliver the best possible care, shared decision making must be upheld and promoted [34], but physicians must be mindful to strike a balance between ethical conduct and optimal patient outcomes.

-

2.

A lack of knowledge of biosimilar therapies: An international survey was conducted to assess medication–class awareness, biosimilar versus reference biologic therapy comprehension, perceptions of clinical trials, and any involvement in advocacy groups. In the USA and EU, a clear link was demonstrated between lack of knowledge and awareness of biosimilars and an increase in the experienced nocebo effect. Only 27% of the general population were aware of what biosimilar products were, and rates of knowledge in clinicians and caregivers fluctuated from 45 to 78% [35, 36]. Better education of both HCPs and patients around biosimilar awareness may help reduce the likelihood of triggering a nocebo effect.

-

3.

A lack of coherence between what is being communicated to patients about biosimilar medications across healthcare by physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and others. One solution would involve improved communication through public relations by reporting clinical and observational results that support the use of biosimilars.

When considering the key triggers, some basic strategies that can be implemented in daily clinical practice may help to avoid/minimise a nocebo effect.

5 Strategies for Clinical Practice

A potential strategy to improve physician–patient communication consists in positive framing. Attribute framing refers to the positive versus negative description of a specific attribute of a single piece of information, e.g. “the chance of survival with cancer is 2/3” versus “the chance of mortality with cancer is 1/3” [37]. Improving the quality of physician–patient interaction/communication can minimise nocebo effects and optimise patient adherence [21].

In late-stage labour, before an epidural injection, women were told one of two things: “We are going to give you a local anaesthetic that will numb the area and you will be comfortable during the procedure” versus “You are going to feel a big bee sting; this is the worst part of the procedure”. Women reported significantly higher rates of pain associated with the second statement. Therefore, including words of encouragement and avoiding totally neutral statements in this setting has demonstrated a reduced nocebo effect and a lower experience of pain [38].

Physicians should strive to avoid instilling negative expectations during the informed consent process, procedural information, and follow-up assessments so that the most effective physician–patient communication can be pursued while unwarranted and untenable nocebo responses can be avoided [39]. In the context of a reference biologic to biosimilar switch, discussion of the equality of the treatments as assessed by independent regulators should be stressed instead of overemphasising the remote chance of a small difference with unknown clinical consequence.

A second important aspect is the knowledge about biosimilars. An immediate need exists to educate HCPs and patients about biosimilars to ensure that informed decisions are made regarding use [35]. Reference to the wealth of evidence available can build physician confidence (Fig. 3)—confidence that is transferred to patients, enabling them to make informed choices with their physician about their healthcare [40].

Reprinted by permission from the RightsLink Permissions Springer Customer Service Centre GmbH: Springer Nature, Rheumatology and Therapy, Treatment Outcomes with Biosimilars: Be Aware of the Nocebo Effect, Rezk MF and Pieper B, copyright 2017

Translating the breadth of data in this field for the patient. Confident HCPs regarding biosimilar agents result in empowered patient treatment decisions in rheumatoid arthritis. HCPs aware of the depth and breadth of biosimilar data and able to explain this information effectively to a patient will result in patient confidence in their treatment choice, ultimately leading to an increase in medication adherence and a reduction in the probability of a nocebo effect [42]. HCP healthcare professional, PD pharmacodynamics, PK pharmacokinetics.

Moreover, a managed switching programme from a reference biologic to a biosimilar may reduce possible nocebo effects, utilising the One Voice package [41]. The One Voice package provides an entire healthcare institution with guidance on lexicon and language use, from receptionist to physician, to ensure a standardised, unified approach to communications around biosimilar medications. This principle ensures that no divergent opinions are being expressed to patients regarding the agreed treatment strategies, and preferably that all HCPs involved in their management ‘speak the same language’. An example of such an approach is the Dutch Hospital Pharmacists/Medical Specialist Biosimilars Toolbox, containing a project plan and training materials, and example letters, etc. [41].

6 Conclusions and Further Work

The nocebo effect should be taken seriously, with proper avoidance planning encouraged. Although examples given here are largely tumour necrosis factor-based, ample research has demonstrated that this is very much a healthcare-wide issue already observed for decades in a variety of disease and treatment situations.

Studies on factors other than perceived diminished efficacy and serious AEs are warranted. These should focus on less tangible factors such as a priori personal beliefs (either those of patients or HCPs), chosen wording in information material, flow of communication and the impact of patient preferences on ease of administration (i.e. injection devices). Results should clarify the potential placebo/nocebo impact of each of these treatment-effect modifying factors.

We believe that successful transition programmes should be based on a comprehensive project plan, including training of all HCPs in biosimilar information and shared decision making, leading to a One Voice approach.

When discussing switching with patients, only the concept of the biosimilar and the available evidence regarding efficacy (non-inferiority) and safety (no additional signals or immunogenicity) should be mentioned. The patient has already been informed of the originator efficacy and safety. We should address the fact that in patients with good disease control, transitioning can be associated with maintenance, but obviously not improvement of the salutary effect of treatment, as the continued treatment is essentially the same. The One Voice package should prevent the expression of divergent opinions to patients. In this way, transition programmes can achieve the full potential of biosimilars—equally effective treatment at lower cost and potentially with increased patient access. It is a societal responsibility of each HCP to support these noble objectives to the benefit of a sustainable and affordable healthcare system.

References

Orwell G. Politics and the English language. 1st ed. London: Penguin Classics; 2013.

Häuser W, Hansen E, Enck P. Nocebo phenomena in medicine: their relevance in everyday clinical practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:459–65.

Planès S, Villier C, Mallaret M. The nocebo effect of drugs. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2016;4:e00208.

Shapiro AK, Shapiro E. The powerful placebo: from ancient priest to modern physician. 1st ed. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998.

Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet. 1978;2:654–7.

Aslaksen PM, Åsli O, Øvervoll M, Bjørkedal E. Nocebo hyperalgesia and the startle response. Neuroscience. 2016;339:599–607.

Gagne JJ, Avorn J, Shrank WH, Schneeweiss S. Refilling and switching of antiepileptic drugs and seizure-related events. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:347–53.

Napadow V, Li A, Loggia ML, Kim J, Mawla I, Desbordes G, et al. The imagined itch: brain circuitry supporting nocebo-induced itch in atopic dermatitis patients. Allergy. 2015;70:1485–92.

Weissenfeld J, Stock S, Lungen M, Gerber A. The nocebo effect: a reason for patients’ non-adherence to generic substitution? Pharmazie. 2010;65:451–6.

Kesselheim AS, Stedman MR, Bubrick EJ, Gagne JJ, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Seizure outcomes following the use of generic versus brand-name antiepileptic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs. 2010;70:605–21.

Mitsikostas DD, Mantonakis LI, Chalarakis NG. Nocebo is the enemy, not placebo. A meta-analysis of reported side effects after placebo treatment in headaches. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:550–61.

Papadopoulos D, Mitsikostas DD. A meta-analytic approach to estimating nocebo effects in neuropathic pain trials. J Neurol. 2012;259:436–47.

Okais C, Gay C, Seon F, Buchaille L, Chary E, Soubeyrand B. Disease-specific adverse events following nonlive vaccines: a paradoxical placebo effect or a nocebo phenomenon? Vaccine. 2011;29:6321–6.

Liccardi G, Senna G, Russo M, Bonadonna P, Crivellaro M, Dama A, et al. Evaluation of the nocebo effect during oral challenge in patients with adverse drug reactions. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2004;14:104–7.

Vernia P, Di Camillo M, Foglietta T, Avallone VE, De Carolis A. Diagnosis of lactose intolerance and the “nocebo” effect: the role of negative expectations. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:616–9.

Voelker R. Nocebos contribute to host of ills. JAMA. 1996;275:345–7.

Pollo A, Torre E, Lopiano L, Rizzone M, Lanotte M, Cavanna A, et al. Expectation modulates the response to subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinsonian patients. NeuroReport. 2002;13:1383–6.

Bootzin RR, Bailey ET. Understanding placebo, nocebo, and iatrogenic treatment effects. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:871–80.

Barsky AJ, Saintfort R, Rogers MP, Borus JF. Nonspecific medication side effects and the nocebo phenomenon. JAMA. 2002;287:622–7.

Mitsikostas DD, Mantonakis L, Chalarakis N. Nocebo in clinical trials for depression: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215:82–6.

Jørgensen KK, Olsen IC, Goll GL, Lorentzen M, Bolstad N, Haavardsholm EA, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 compared with maintained treatment with originator infliximab (NOR-SWITCH): a 52-week, randomised, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2304–16.

Khan NA, Spencer HJ, Abda E, Aggarwal A, Alten R, Ancuta C, et al. Determinants of discordance in patients’ and physicians’ rating of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:206–14.

Nikiphorou E, Radner H, Chatzidionysiou K, Desthieux C, Zabalan C, van Eijk-Hustings Y, et al. Patient global assessment in measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the literature. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18:251.

Tweehuysen L, Huiskes VJB, van den Bemt BJF, Vriezekolk JE, Teerenstra S, van den Hoogen FHJ, et al. Open-label non-mandatory transitioning from originator etanercept to biosimilar SB4: 6-month results from a controlled cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.40516 (epub ahead of print).

Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, de Jong AJL, van der Laan WH, van den Hoogen FHJ, et al. Subjective complaints as the main reason for biosimilar discontinuation after open-label transition from reference infliximab to biosimilar infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:60–8.

Tweehuysen L, Huiskes VJB, van den Bemt BJF, van den Hoogen FHJ, den Broeder AA. FRI0200 Higher acceptance and persistence rates after biosimilar transitioning in patients with a rheumatic disease after employing an enhanced communication strategy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:557.

Nikiphorou E, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, Asikainen J, Kokko A, Rannio T, et al. Clinical effectiveness of CT-P13 (infliximab biosimilar) used as a switch from Remicade (infliximab) in patients with established rheumatic disease. Report of clinical experience based on prospective observational data. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2015;15:1677–83.

Glintborg B, Sørensen IJ, Jensen DV, Krogh NS, Loft AG, Espesen J, et al. A nationwide non-medical switch from originator to biosimilar infliximab in patients with inflammatory arthritis. eleven months’ clinical outcomes from the Danbio Registry. Abstract 951. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/clinical-and-immunogenicity-outcomes-after-switching-treatment-from-innovator-infliximab-to-biosimilar-infliximab-in-rheumatic-diseases-in-daily-clinical-practice/. Accessed 1 Jan 2018.

Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, de Jong AJL, van der Laan WH, van den Hoogen FHJ, et al. Clinical and immunogenicity outcomes after switching treatment from innovator infliximab to biosimilar infliximab in rheumatic diseases in daily clinical practice. Abstract 627. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10). https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/clinical-and-immunogenicity-outcomes-after-switching-treatment-from-innovator-infliximab-to-biosimilar-infliximab-in-rheumatic-diseases-in-daily-clinical-practice/. Accessed 1 Jan 2018.

Glintborg B, Sørensen IJ, Loft AG, Esbesen J, Lindegaard H, Jensen DV, et al. FRI0190 Clinical outcomes from a nationwide non-medical switch from originator to biosimilar etanercept in patients with inflammatory arthritis after 5 months follow-up. Results from the danbio registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:553–4.

Scherlinger M, Germain V, Labadie C, Barnetche T, Truchetet ME, Bannwarth B, et al. Switching from originator infliximab to biosimilar CT-P13 in real-life: the weight of patient acceptance. Jt Bone Spine. 2017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.10.003 (epub ahead of print).

Boone NW, Liu L, Romberg-Camps MJ, Duijsens L, Houwen C, van der Kuy PHM, et al. The nocebo effect challenges the non-medical infliximab switch in practice. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74:655–61.

Rodriguez-Raecke R, Doganci B, Breimhorst M, Stankewitz A, Buchel C, Birklein F, et al. Insular cortex activity is associated with effects of negative expectation on nociceptive long-term habituation. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11363–8.

Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J, Burmester G, Chatzidionysiou K, Dougados M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:960–77.

Jacobs I, Singh E, Sewell KL, Al-Sabbagh A, Shane LG. Patient attitudes and understanding about biosimilars: an international cross-sectional survey. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:937–48.

Cohen H, Beydoun D, Chien D, Lessor T, McCabe D, Muenzberg M, et al. Awareness, knowledge, and perceptions of biosimilars among specialty physicians. Adv Ther. 2017;33:2160–72.

Akl EA, Oxman AD, Herrin J, Vist GE, Terrenato I, Sperati F, et al. Framing of health information messages. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD006777. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006777.pub2.

Varelmann D, Pancaro C, Cappiello EC, Camann WR. Nocebo-induced hyperalgesia during local anesthetic injection. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:868–70.

Colloca L, Finniss D. Nocebo effects, patient-clinician communication, and therapeutic outcomes. JAMA. 2012;307:567–8.

Edwards C, editor. Switching patients from originator to biosimilar medications in rheumatoid arthritis: limiting the ‘nocebo’ effect. Madrid: EULAR. 2017.

Federatie Medisch Specialisten, NVZA. NVZA Toolbox Biosimilars: Een praktische handleiding voor succesvolle implementatie van biosimilars in de medisch specialistische zorg. 2017. http://nvza.nl/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NVZA-Toolbox-biosimilars_7-april-2017.pdf. Accessed Mar 2018.

Rezk MF, Pieper B. Treatment outcomes with biosimilars: be aware of the nocebo effect. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4:209–18.

Acknowledgements

Rugina Ali, Sarah Balston and Philip Ford, from Syneos Health wrote the first draft of the manuscript based on input from authors, and Elisabeth Beatty and Robert Harries from Syneos Health copyedited and styled the manuscript as per journal requirements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This article was funded by Biogen International GmbH. Biogen International GmbH provided funding for medical writing support in the development of this paper, and reviewed and provided feedback on the paper to the authors. The authors had full editorial control of the paper, and provided their final approval of all content.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval regarding the version to be published.

Conflict of interest

Lars Kristensen has received grant/research support from UCB, Biogen, Janssen pharmaceuticals, and Novartis, and speakers bureau support from Pfizer, AbbVie, Amgen, UCB, BMS, Biogen, MSD, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, and Janssen pharmaceuticals. Rieke Alten has received honoraria from Biogen for advisory board meetings. Luis Puig has received grants/research support from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB; has received honoraria or consultation fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Baxalta, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Gebro, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Merck-Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Sandoz, and UCB; and has participated in a company sponsored speaker’s bureau with Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer. Sandra Philipp has received honoraria for speaker services from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS GmbH, Lilly, Leo Pharma, Celgene, Hexal, Janssen, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis and UCB Pharma; advisory board services from AbbVie, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, MSD and Novartis; and investigator services from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly, GSK, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma and VBL Therapeutics. Tore K. Kvien has received fees for speaking and/or consulting from AbbVie, Biogen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Epirus, Hospira, Merck-Serono, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Oktal, Orion Pharma, Hospira/Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz and UCB and received research funding to Diakonhjemmet Hospital from AbbVie, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. Maria Antonia Mangues and Frank van den Hoogen have received consultancy fees from Biogen, Celltrion, Mundipharma and Roche. Karel Pavelka has received honoraria for lectures and consultations from AbbVie, Roche, Egis, BMS, MSD, Pfizer, Biogen, UCB, Amgen and Novartis. Arnold G. Vulto has received consulting and speaker’s bureau honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, EGA/Medicines for Europe, Mundipharma, Pfizer/Hospira, Roche, Novartis/Sandoz, Samsung Bioepis, F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Eli Lilly, Febelgen and Hexal/Sandoz Ltd; he is a co-founder and has a societal interest in the Generics & Biosimilar Initiative (GaBI), Biosimilars Initiative, the Netherlands (Chair) and the KU Leuven MABEL research fund.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kristensen, L.E., Alten, R., Puig, L. et al. Non-pharmacological Effects in Switching Medication: The Nocebo Effect in Switching from Originator to Biosimilar Agent. BioDrugs 32, 397–404 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-018-0306-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-018-0306-1