Abstract

Background

Effective mental health interventions may reduce the impact that mental health problems have on young people’s well-being. Nevertheless, little is known about the cost effectiveness of such interventions for children and adolescents.

Objectives

The objectives of this systematic review were to summarize and assess recent health economic evaluations of universal mental health interventions for children and adolescents aged 6–18 years.

Methods

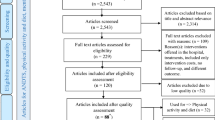

Four electronic databases were searched for relevant health economic studies, using a pre-developed search algorithm. Full health economic evaluations evaluating the cost effectiveness of universal mental health interventions were included, as well as evaluations of anti-bullying and suicide prevention interventions that used a universal approach. Studies on the prevention of substance abuse and those published before 2013 fell outside the scope of this review. Study results were summarised in evidence tables, and each study was subject to a systematic quality appraisal.

Results

Nine studies were included in the review; in six, the economic evaluation was conducted alongside a clinical trial. All studies except one were carried out in the European Union, and all but one evaluated school-based interventions. All evaluated interventions led to positive incremental costs compared to their comparators and most were associated with small increases in quality-adjusted life-years. Almost half of the studies evaluated the cost effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy-based interventions aimed at the prevention of depression or anxiety, with mixed results. Cost-effectiveness estimates for a parenting programme, a school-based social and emotional well-being programme and anti-bullying interventions were promising, though the latter were only evaluated for the Swedish context. Drivers of cost effectiveness were implementation costs; intervention effectiveness, delivery mode and duration; baseline prevalence; and the perspective of the evaluation. The overall study quality was reasonable, though most studies only assessed short-term costs and effects.

Conclusion

Few studies were found, which limits the possibility of drawing strong conclusions about cost effectiveness. There is some evidence based on decision-analytic modelling that anti-bullying interventions represent value for money. Generally, there is a lack of studies that take into account long-term costs and effects.

Systematic Review Registration Number

CRD42019115882.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Adolescent mental health in the European Region. 2018. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/383891/adolescent-mh-fs-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

Suhrcke M, Pillas D, Selai C. Economic aspects of mental health in children and adolescents. Social cohesion for mental well-being among adolescents. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2008.

Fenwick-Smith A, Dahlberg EE, Thompson SC. Systematic review of resilience-enhancing, universal, primary school-based mental health promotion programs. BMC Psychol. 2018;6(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-018-0242-3.

Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Wolfenden L, Hodder RK, et al. Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(10):813–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.07.780.

Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre. Threshold values for cost-effectiveness in health care. KCE Reports, report no. 100C. Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre; 2008.

York Health Economics Consortium. A glossary of health economic terms—economic evaluation. York. 2016. https://www.yhec.co.uk/glossary/. Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

Mihalopoulos C, Chatterton ML. Economic evaluations of interventions designed to prevent mental disorders: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9(2):85–92.

Mihalopoulos C, Vos T, Pirkis J, Carter R. The economic analysis of prevention in mental health programs. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:169–201.

Haggerty RJ, Mrazek PJ. Can we prevent mental illness? Bull N Y Acad Med. 1994;71(2):300–6.

Wang LY, Nichols LP, Austin SB. The economic effect of Planet Health on preventing bulimia nervosa. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(8):756–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.105.

Mihalopoulos C, Sanders MR, Turner KM, Murphy-Brennan M, Carter R. Does the triple P-Positive Parenting Program provide value for money? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41(3):239–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670601172723.

Le LK-D, Hay P, Mihalopoulos C. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies of prevention and treatment for eating disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;52(4):328–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417739690.

Amos A. Assessing the cost of early intervention in psychosis: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(8):719–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412450470.

Bustamante Madsen L, Eddleston M, Schultz Hansen K, Konradsen F. Quality assessment of economic evaluations of suicide and self-harm interventions. Crisis. 2018;39(2):82–95. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000476.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Thielen FW, Van Mastrigt G, Burgers LT, Bramer WM, Majoie H, Evers S, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for clinical practice guidelines: database selection and search strategy development (part 2/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):705–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2016.1246962.

Van Mastrigt GA, Hiligsmann M, Arts JJ, Broos PH, Kleijnen J, Evers SM, et al. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: a five-step approach (part 1/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):689–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2016.1246960.

Wijnen B, Van Mastrigt G, Redekop WK, Majoie H, De Kinderen R, Evers S. How to prepare a systematic review of economic evaluations for informing evidence-based healthcare decisions: data extraction, risk of bias, and transferability (part 3/3). Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(6):723–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737167.2016.1246961.

Saxena S, Jané-Llopis E, Hosman C. Prevention of mental and behavioural disorders: implications for policy and practice. World Psychiatry. 2006;5(1):5–14.

American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy in the promotion of health and well-being. Am J Occup Ther 2013;67(6_Supplement):S47–S59. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.67S47.

Campbell and Cochrane Economics Methods Group and Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre. CCEMG - EPPI-Centre cost converter. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/costconversion/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: consensus on health economic criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(2):240–5.

Humphrey N, Hennessey A, Lendrum A, Wigelsworth M, Turner A, Panayiotou M, et al. The PATHS curriculum for promoting social and emotional well-being among children aged 7–9 years: a cluster RCT. Public Health Research. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2018.

Persson M, Wennberg L, Beckman L, Salmivalli C, Svensson M. The cost-effectiveness of the Kiva Antibullying Program: results from a decision-analytic model. Prev Sci. 2018;19(6):728–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0893-6.

Ahern S, Burke LA, McElroy B, Corcoran P, McMahon EM, Keeley H, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of school-based suicide prevention programmes. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;27(10):1295–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1120-5.

Garmy P, Clausson EK, Berg A, Steen Carlsson K, Jakobsson U. Evaluation of a school-based cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program. Scand J Public Health. 2019;47(2):182–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817746537.

Lee YY, Barendregt JJ, Stockings EA, Ferrari AJ, Whiteford HA, Patton GA, et al. The population cost-effectiveness of delivering universal and indicated school-based interventions to prevent the onset of major depression among youth in Australia. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2017;26(5):545–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796016000469.

Ulfsdotter M, Lindberg L, Månsdotter A. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the Swedish universal parenting program all children in focus. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145201. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145201.

Stallard P, Skryabina E, Taylor G, Anderson R, Ukoumunne OC, Daniels H, et al. Public Health Research. A cluster randomised controlled trial comparing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a school-based cognitive-behavioural therapy programme (FRIENDS) in the reduction of anxiety and improvement in mood in children aged 9/10 years. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2015.

Beckman L, Svensson M. The cost-effectiveness of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: results from a modelling study. J Adolesc. 2015;45:127–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.07.020.

Anderson R, Ukoumunne OC, Sayal K, Phillips R, Taylor JA, Spears M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of classroom-based cognitive behaviour therapy in reducing symptoms of depression in adolescents: a trial-based analysis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(12):1390–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12248.

InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Cognitive behavioral therapy; 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279297/. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

York Health Economics Consortium. A Glossary of health economic terms—quality adjusted life year. York: York Health Economics Consortium; 2016. https://www.yhec.co.uk/glossary/. Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

York Health Economics Consortium. A glossary of health economic terms—utility. York: York Health Economics Consortium; 2016. https://www.yhec.co.uk/glossary/. Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

Annemans L. Gezondheidseconomie voor niet-economen—Een inleiding tot de begrippen, methoden en valkuilen van de gezondheidseconomische evaluatie. 4th ed. Ghent: Academia Press; 2010.

The University Of Sheffield. Paediatric quality of life. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/scharr/sections/heds/mvh/paediatric. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

Serrano-Aguilar P, Ramallo-Fariña Y, Trujillo-Martín Mdel M, Muñoz-Navarro SR, Perestelo-Perez L, De Las Cuevas-Castresana C. The relationship among mental health status (GHQ-12), health related quality of life (EQ-5D) and health-state utilities in a general population. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2009;18(3):229–39.

Beckman L, Svensson M, Frisén A. Preference-based health-related quality of life among victims of bullying. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(2):303–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1101-9.

The University Of Sheffield. The SF-6D: a new, internationally adopted measure for assessing the cost-effectiveness of health care interventions. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/economics/research/impact/sf6d. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, de Noordhout CM, Polinder S, Havelaar AH, et al. Disability weights for the global burden of disease 2013 study. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(11):e712–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(15)00069-8.

Persson M, Svensson M. The willingness to pay to reduce school bullying. Econ Educ Rev. 2013;35:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.02.004.

Fazel M, Hoagwood K, Stephan S, Ford T. Mental health interventions in schools 1: mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):377–87.

O’Reilly M, Svirydzenka N, Adams S, Dogra N. Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(7):647–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1530-1.

Boot WR, Simons DJ, Stothart C, Stutts C. The pervasive problem with placebos in psychology: why active control groups are not sufficient to rule out placebo effects. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2013;8(4):445–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613491271.

Mihalopoulos C, Vos T, Pirkis J, Carter R. The population cost-effectiveness of interventions designed to prevent childhood depression. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e723–30. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1823.

Simon E, Dirksen C, Bögels S, Bodden D. Cost-effectiveness of child-focused and parent-focused interventions in a child anxiety prevention program. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(2):287–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.008.

Simon E, Dirksen CD, Bogels SM. An explorative cost-effectiveness analysis of school-based screening for child anxiety using a decision analytic model. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(10):619–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0404-z.

Lynch FL, Hornbrook M, Clarke GN, Perrin N, Polen MR, O’Connor E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an intervention to prevent depression in at-risk teens. JAMA Psychiatry. 2005;62(11):1241–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1241.

O’Mahony JF, Newall AT, van Rosmalen J. Dealing with time in health economic evaluation: methodological issues and recommendations for practice. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(12):1255–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-015-0309-4.

York Health Economics Consortium. A glossary of health economic terms—time horizon. York: York Health Economics Consortium; 2016. https://www.yhec.co.uk/glossary/. Accessed 17 Jan 2019.

Hummel S, Naylor P, Chilcott J, Guillaume L, Wilkinson A, Blank L, et al. Cost effectiveness of universal interventions which aim to promote emotional and social wellbeing in secondary schools. Sheffield: University of Sheffield; 2009.

Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M. Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: the economic case. London: Department of Health; 2011.

Zechmeister I, Kilian R, McDaid D, MHEEN Group. Is it worth investing in mental health promotion and prevention of mental illness? A systematic review of the evidence from economic evaluations. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-20.

Sari N, de Castro S, Newman FL, Mills G. Should we invest in suicide prevention programs? J Socio Econ. 2008;37(1):262–75.

Gray D, Dawson KL, Grey TC, McMahon WM. Best practices: the Utah Youth Suicide Study: best practices for suicide prevention through the juvenile court system. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(12):1416–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.014162011.

Byford S, Harrington R, Torgerson D, Kerfoot M, Dyer E, Harrington V, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of a home-based social work intervention for children and adolescents who have deliberately poisoned themselves. Results of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:56–62. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.174.1.56.

EBSCO Information Services. ERIC. https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/eric. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

American Psychological Association. PsycINFO®. https://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/psycinfo/index.aspx. Accessed 18 Jan 2019.

Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs en Vorming. Leerplicht van 6 tot 18 jaar. https://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/leerplicht-van-6-tot-18-jaar. Accessed 3 Mar 2019.

World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Adolescent health and development. 2019. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/child_adolescent/topics/adolescent_health/en/. Accessed 26 Aug 2019.

Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):223–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-4642(18)30022-1.

Godoy Garraza L, Peart Boyce S, Walrath C, Goldston DB, McKeon R. An economic evaluation of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Program. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(1):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12321.

World Health Organization. Early child development. 2019. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/themes/earlychilddevelopment/en/. Accessed 26 Aug 2019.

Anderson R. Systematic reviews of economic evaluations: utility or futility? Health Econ. 2010;19(3):350–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1486.

International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook database. 2018. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2019/01/weodata/index.aspx.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MS and AW developed the search strategy and screened the studies for eligibility. MS extracted and synthesised data with input from AW and LA. MS drafted the manuscript, with input from AW, LA, SS, KP and NV. MS acts as the overall guarantor for the systematic review and accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the review and the decision to publish.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Masja Schmidt, Amber Werbrouck, Nick Verhaeghe, Koen Putman, Steven Simoens and Lieven Annemans declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to this systematic review.

Funding

This study was funded by ‘Vlaams Agentschap voor Zorg en Gezondheid’ (VAZG, The Flemish Agency for Care and Health, grant number AZG/PREV/GE/2016-01). VAZG was involved in the selection of the topic but had no role in study selection, data collection, data synthesis or in writing the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, M., Werbrouck, A., Verhaeghe, N. et al. Universal Mental Health Interventions for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Health Economic Evaluations. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 18, 155–175 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00524-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00524-0