Abstract

Key message

Prescribed burning applied after a dry year increased (fall burns) or had no effect (spring burns) on pine resilience, measured as the capacity to reach pre-drought growth levels compared with unburned pines. In fall burns, there was a larger increase in resilience when the impact of drought and burning on pines was low and burning caused a significant release from tree competition.

Context

Prescribed burning after a dry year can decrease a tree’s resistance (inverse of growth reduction during disturbance); however, burning can increase resource availability and consequently tree resilience (capacity to reach pre-disturbance growth levels). In addition, the burning season can affect the latewood to earlywood ratio (latewood:earlywood) and thus have an impact on tree-ring density.

Aims

To study the effects of two consecutive disturbances (drought and burning) on Pinus nigra spp. salzmannii and Pinus sylvestris in terms of (i) total tree-ring resistance, (ii) total tree-ring, earlywood and latewood resilience, and (iii) post-stress latewood:earlywood.

Methods

We selected drought-affected trees (control) and drought-and-burning-affected trees (burned) for tree-ring sampling. For each tree, we measured total tree-ring, earlywood, and latewood widths to determine resilience and resistance indices and calculated pre- and post-stress latewood:earlywood as indicators of tree-ring density. We used linear mixed-effects models to relate these response variables to the pine species, burning characteristics, and competition release.

Results

Resistance was higher in control trees than burned trees. P. nigra showed lower resistance than P. sylvestris but higher resilience. Resistance positively influenced resilience. Specifically, as resistance increased, total tree-ring and latewood resilience increased significantly in pines burned during the fall compared with those burned in spring or control pines. In fall burns, the pines’ resilience increased, especially when pines were significantly released from tree competition. In P. nigra, post-stress latewood:earlywood increased after fall burns as pre-stress latewood:earlywood decreased.

Conclusion

Prescribed burning can be a valuable management tool for overcoming the effects of a dry year on tree growth by increasing resilience, especially in P. nigra.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Comparing tree growth before, during and after a drought event can be used as a proxy of tree resilience and resistance (Lloret et al. 2011). Resilience can be defined as the capacity to return to pre-disturbance functioning and growth levels (Holling 1973). However, resilience per se does not consider the impact of the disturbance; therefore, resistance, which is the reversal of the reduction in ecological performance during a disturbance (Kaufman 1982), can be included in the resilience analysis to avoid underestimating the resilience (Lloret et al. 2011).

Successive drought events can deplete an individual tree’s reserves, diminishing tree vitality and ultimately causing tree death (Galiano et al. 2011). If drought-weakened trees are further stressed by natural or management perturbations, such as prescribed burning, resilience can be affected because fire injured trees need their stored carbohydrates to replenish killed or injured tissues (Varner et al. 2009). In contrast, prescribed burning can have positive effects on tree growth as it increases resource availability by removing understory and small trees (Battipaglia et al. 2014) and releasing nutrients after the fire (Certini 2005). Although some studies have analyzed the effect on tree growth of prescribed burning and subsequent drought events (Bottero et al. 2017; Collins et al. 2014; Lloret et al. 2011), few studies have studied the reverse situation: prescribed burning after a drought event.

To fully understand a tree’s resilience to overlapping disturbances it is necessary to know the relative intensities (Bansal et al. 2013) and the stochastic extrinsic factors associated with the disturbances (e.g., release from tree competition) (Lloret et al. 2011; Van Mantgem et al. 2016; Van Mantgem et al. 2018). Resistance to drought and burning together with the fire severity experienced by each individual tree (e.g., crown, root and stem injury, death of neighbor trees), the specific characteristics of prescribed burns (e.g., intensity, season), tree attributes (e.g., species, size, tree reserves status), and time since burning, are all major sources of variability in tree resilience after drought and prescribed burning.

Trees that have survived drought events generally have a higher proportion of latewood compared with those that succumb to drought (Martinez-Meier et al. 2008). The tracheids in latewood have a smaller diameter and thicker cell walls than earlywood tracheids. Therefore, a higher proportion of latewood than earlywood likely increases the resistance to the future embolism of upcoming drought events. Burning season can influence the pine’s future resistance to cavitation because burning in spring or fall could have different impacts on the development of the next seasonal growth, producing changes in the proportion of latewood to earlywood in a tree ring. However, fire stem injury could lead to a lasting reduction in xylem conductivity due to conduit wall deformation, resulting in a permanent reduction in hydraulic safety and increasing the likelihood of embolism (Michaletz et al. 2012; Battipaglia et al. 2016; Bär et al. 2018).

As regards species, the boreo-alpine P. sylvestris L. is less tolerant to drought than the sub-Mediterranean P. nigra spp. salzmannii (Dunal) Franco (Martinez-Vilalta and Piñol 2002). P. nigra is more fire resistant than P. sylvestris due to its thicker bark, thicker needles, and higher canopy base height (see Fernandes et al. 2008 for review), which is evidenced by the lower mortality of P. nigra after prescribed burning compared with P. sylvestris (Fernandes et al. 2008; Valor et al. 2017). In terms of iso-hydric behavior, combining tree growth data with wood isotope C information can help to determine more specifically the physiological response of each species to the combined effect of fire and drought. δ13C is a good indicator of plant intrinsic water-use efficiency (WUEi) (Farquhar et al. 1989). It reflects the balance between assimilation rate and stomatal conductance, and thus is an indicator of the internal regulation of carbon uptake and water losses (Saurer et al. 2004) during prescribed burning (Battipaglia et al. 2016). Whereas earlywood is usually formed from carbohydrates assimilated in the previous year (Eilmann et al. 2010), latewood carbon isotope values are clearly related to the current environmental conditions and can contribute to explaining the physiological mechanism behind the growth during and after the disturbance. Thus, if prescribed burning enhances nutrient and water availability due to a reduction in tree competition, then WUEi may decrease (as observed in previous studies by Battipaglia et al. 2014). However, if fire causes tree damage, it is plausible that stomata conductance is reduced, and therefore, WUEi would increase (Niccoli et al. 2019).

This study takes advantage of a series of moderate-intensity prescribed burns that induced around 10–15% tree mortality 2 years post-burning (Valor et al. 2017). The burns were carried out in the spring and fall of 2013, 1 year after the drought in 2012, which was one of the driest years recorded in the region (Sánchez-Costa et al. 2015). We studied the effects of drought and burning season on total tree-ring, and earlywood and latewood resilience of P. nigra spp. salzmannii and P. sylvestris. We used dendrochronological and stable isotope analysis and selected pines of similar sizes without any apparent damage to the crown but in which stem or basal stem injury was evident.

We hypothesized that applying prescribed burning the year after a drought would increase pine resilience in comparison with unburned pines due to the release from resource competition induced by burning. This effect would be species-specific, as P. sylvestris is more sensitive to fire and drought than P. nigra. It would also be resistance dependent, as the magnitude of the impact of drought and/or burning on tree growth will determine the resilience capacity of individual pines. Finally, we hypothesized that burning season would have different impacts on the development of the next seasonal growth.

Understanding to what extent prescribed burning and burning season may exacerbate, cancel out or reverse the effects of drought on the resilience capacity of trees can contribute to the prescription of this management technique. This is an important issue given that drought frequency and intensity is predicted to increase with climate change.

2 Methodology

2.1 Study site, experimental design, and prescribed burning

The study was performed in two localities in the foothills of the Pyrenees, Miravé (41.9515° N, 1.4494° E) and Lloreda (42.0569° N, 1.5706° E), in the NE Iberian Peninsula. We selected one mixed P. sylvestris and P. nigra stand in each locality. Within each stand, we selected two paired sites (1 ha each) to perform prescribed burning either in spring or fall. One plot (30 × 30 m) in each of the four sites, was set up to monitor the effects of prescribed burning on tree growth and pine mortality.

The climate is sub-Mediterranean with a mean annual rainfall of 748 mm in Lloreda and of 677.3 in Miravé, and mean temperature of 11.4 °C in Lloreda and 11.5 °C in Miravé. The slope of all the plots was around 25–30% in both localities. Miravé plots were north oriented at an altitude of 723 m.a.s.l and Lloreda plots were northeast oriented at an altitude of 749 m.a.s.l. Soils developed from calcareous colluviums, classified as Calcaric inceptisols (FAO 2006), they were between 0.5 and 1 m deep, and basic (pH 6.8–7.5) with a fine texture.

At both sites, the forest overstory was dominated by Pinus nigra ssp. salzmanii (Dunal) Franco and P. sylvestris L. and broadleaf trees (i.e., Quercus pubescens Willd., Acer monspessulanum L., Sorbus aria (L.) Crantz) were also common. The understory was composed mainly of Buxus sempervirens L. and deciduous species (e.g., Lonicera etrusca Santi, Viburnum lantana L., Amelanchier ovalis Medik.). Other evergreen shrubs were also common in the understory (e.g., Juniperus oxycedrus L., Q. coccifera L.). The forest characteristics were similar across plots except for the understory phytovolume, which was lower in the Lloreda spring burn, and the basal area of the stands, which was higher in the Lloreda fall burn (Table 1).

Prescribed burning was carried out in late spring (5 June at Lloreda and 12 June at Miravé, 2013) and fall (17 October at Miravé and 8 November at Lloreda, 2013) by the Forest Actions Support Group (GRAF) of the Autonomous Catalan Government (Generalitat de Catalunya), to reduce surface and ladder fuels and thus reduce fire hazard. All burns were carried out following a strip headfire ignition pattern under similar meteorological conditions, although forest floor moisture was much lower in fall burns than in spring burns (Table 1). Fire behavior was comparable among sites and fire seasons, except in the Lloreda fall burn (Table 1) where the combustion time above 120°C at the soil surface was longer than in the other plots. Immediately after prescribed burning, we visually estimated the proportion of white ash in 1 m radius from the tree center for each tree. White ash indicates smoldering and potential damage to the basal stem and root collar (McCandliss 2002). Stem injury was characterized by bole scorch height (BSH) (Wyant et al. 1986). We measured the maximum (BSHmax) and minimum (BSHmin) bole scorch height. One week after prescribed burning, the crown volume scorched was visually estimated to the nearest 5% as the change in needle color resulting from heat transferred via convection. Details on tree mortality over time and on the experimental design for determining combustion times are reported in Valor et al. 2017.

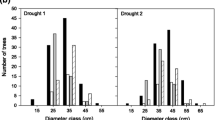

2.2 Tree selection and tree competition index

Pine’s resilience was analyzed by randomly selecting at each plot 15 trees per species and burning season, with similar DBH and without any damage on the crown (Table 2). Tree sampling was representative of the population of trees that experienced prescribed burning, as most pines, 70% of pines with DBH between 15 and 25 cm, did not experience crown damage. Additionally, we select 15 control trees per species growing in an adjacent site left unburned.

For each burned tree, we computed the Hegyi’s competition index (CI) (Hegyi 1974) before burning in 2012 (CI12) and 2 years post-burning in 2015 (CI15) (Table 2). The Hegyi’s index is a distance-dependent tree competition index, and it was calculated using the pairwise function of the Siplab package (Garcia 2014) for each year as follows:

where CIi is the competition index for the subject tree i, DBH the diameter at breast height, distij the distance between the subject tree i and the competitor tree j, and n is the number of competitors in the neighborhood zone. A search radius of 3.5 m defined the neighborhood zone. Following Lorimer (1983), the radius was defined by multiplying the mean crown radius of overstory, 1 m, by 3.5. Then, to quantify the release from tree competition experienced by each tree, we compute a relative competition index (RCI15) as the difference between pre (CI12) and post-burning competition (CI15) indices relative to pre-burning levels (Table 2).

2.3 Tree-ring measurements

A total of 176 pines were cored to the pith during November and December 2016. Two cores per tree were extracted with an increment borer with a 4.5-mm diameter at a 50-cm height above the ground, with an angle of 120° between them. Cores were prepared following standard dendrochronological techniques (Stokes and Smiley 1968). Total tree-ring, earlywood and latewood widths of each annual tree-ring were measured from year 2015 until the pith, as latewood in early fall 2016 was still not defined in all cores. We used a Lintab 3 measuring system coupled to the TSAP tree-ring software (Frank Rinn, Heidelberg, Germany), with a precision of 0.001 mm. Cores of each locality, species, and plot were dated and visually cross-dated by comparing characteristic narrow rings present in all trees to detect the presence of false and missing rings. Cross-dating was validated in the 12 chronologies developed using the COFECHA software (Holmes 1983), which calculates cross-correlations among individual series of tree growths.

Using the Dendrochronology Program Library (dplR) package in R, Version 2.10.1, tree-ring series were detrended with a cubic smoothing spline with a 50% frequency response cutoff of 10 years to remove long-term growth trends embedded in the raw tree-ring series that were thought to be induced by non-climatic influences, such as aging and competition between trees (Fritts 1976). The standard chronology was calculated as the bi-weight robust mean value of each detrended series. In addition, individual series were subjected to autoregressive modeling and also averaged using a bi-weight robust mean to obtain the residual chronology (Cook 1985). The residual chronology was used to analyze climate-growth relationships because by removing the autoregressive component it is possible to determine stronger more reliable correlations with climate. We used the standard chronology to calculate common dendrochronological statistical measures, and thus determine by how much growth for any given year has been influenced by growth in the preceding year.

Total tree-ring, earlywood, and latewood were converted into basal area increments (BAI) using the INBAI function of the Dplr package (Bunn 2008). We preferred to use BAI over raw ring tree widths because it is less dependent on tree age and avoids the need for detrending, which could obscure the effects of reduction in tree competition on tree growth as it removes the low-frequency variability (Biondi 1999).

We studied tree responses to a dry year that occurred in 2012, just 1 year before prescribed burning was applied. To determine whether the 2012 event was a year with significant growth reduction in the two species we used the package PointRes (van der Maaten-Theunissen et al. 2015) (Fig. 5 Annex1).

2.4 Resistance and resilience indices

The resistance and resilience indices were calculated as in Lloret et al. (2011) as follows:

where BAISt is the average BAI during the stress period (drought 2012 and prescribed burning 2013), BAIpreSt is the average BAI of the 3 years preceding the stress period (2009 to 2011), and BAIpostSt is the average BAI of the 2 years after the stress period (2014 and 2015). Resilience was also calculated separately for years 2014 and 2015. Resilience was calculated for total tree-ring, earlywood, and latewood. Resistance was only calculated for total tree-ring, as the earlywood of the trees burned during the fall of 2013 was unaffected by fire. Thereafter, the resilience and resistance indices refer to the 2012 drought; however, these indices were calculated for individuals that were only drought-affected (control) and for individuals that were drought-and-burning-affected (burned).

To understand the effect of burning season on resistance to future drought events we used the latewood to earlywood ratio (latewood:earlywood) as an estimate of wood density (Bodig and Jayne 1993). The latewood:earlywood is an important hydrological trait as a higher proportion of latewood increases a tree’s resistance to embolism at low water potential and can act as water storage (Domec and Gartner 2002). For each tree, we subtracted the mean pre-stress latewood:earlywood (2006–2012) from the mean post-stress latewood:earlywood (2014–2015) (DIF_latewood:earlywood). Positive values of DIF_latewood:earlywood indicate higher latewood:earlywood than in the pre-stress period and negative values indicate lower latewood:earlywood than in the pre-stress period.

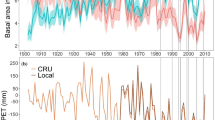

2.5 Climatic data

Monthly precipitation (P) and temperature (T) from 1975 to 2015 were obtained for both sites using climatic records and projections elaborated by the Spanish Meteorological Agency (AEMET) (see Ninyerola et al. 2000 for the spatial resolution of the original climatic data and the approach applied to downscale the climatic records). Monthly potential evapotranspiration (PET) was estimated using the Thornthwaite (1954) method. For each month, the difference between P and PET (P-PET) was calculated as a measure of water availability.

2.6 Carbon isotopes

Once we had obtained the chronologies for each site, species and burning season, we selected the five trees with the highest inter-series correlation with a similar age. One additional core was extracted from these selected trees using a 7-mm-diameter borer with a drill at a 50-cm height. We selected the section corresponding to the period 2011–2015 from each sampled core. Earlywood and latewood were divided and separated for each year. The earlywood and latewood of the five trees were pooled for each combination of year, site, species and burning season. To estimate the standard deviation of the samples, the earlywood and latewood of 2011 were not pooled. Pooled and individual samples were ground with a milling chamber. The carbon stable isotope composition was measured at the IRMS Lab of University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli” by continuous-flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry (Delta V Advantage, Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) using 0.06 mg of dry matter for 13C measurements. The δ13C series were corrected for the Suess Effect (decrease in δ13C of atmospheric CO2 since the beginning of industrialization) resulting from the emission of fossil carbon dioxide, which is depleted in 13C (Francey et al. 1999). The corrected series were used for all statistical analyses. Isotopic compositions are expressed in delta notation (‰) in accordance with accepted Vienna PeeDee Belemnite reference standards for carbon isotope values. The standard deviation for the repeated analysis of an internal standard (commercial cellulose) was lower than 0.2‰ for C.

2.7 Data analysis

A linear mixed-effects model (LMM) was used to test whether resistance and resilience in P. nigra and P. sylvestris differed between control (drought-affected trees) and burned trees (drought-and-burning-affected trees), and by how much resilience was influenced by resistance. Thus, we modeled resistance as a function of burning treatment (burned and control trees) with species as fixed factors; and total tree-ring, earlywood and latewood resilience as a function of burning season (control, fall, and spring burns), species, and resistance.

To test whether resistance and resilience were influenced by prescribed burning characteristics, we modeled, using LMM, resistance as a function of BSHmin and burning season (spring and fall); and total tree-ring, earlywood, and latewood resilience as a function of pine species, resistance, BSHmin, RCI15 (release from tree competition), and CI12 (pre-burning competition index). Models were developed separately for each burning season and for the whole post-stress period and separately for 2014 and 2015.

To test the influence of burning season and pre-stress latewood:earlywood on post-stress latewood:earlywood, for each species we modeled, using LMM, DIF_latewood:earlywood as a function of burning season and pre-stress latewood:earlywood.

Model selection was based on a robust form of Akaike’s information criterion (AICc) (Burnham and Anderson 2004). All models included two-way interactions except for the interaction between species and C12. Maximum likelihood was used for computing the AICc, while restricted maximum likelihood was used to estimate model coefficients. All mixed models developed included a random factor (locality). Residuals of the final mixed models did not show a pattern. Highly correlated explanatory variables were not used. All analyses were conducted with the software R (v. 3.2.1, the R Foundation for Statistical Computing) using the package nlme (Pinheiro et al. 2007) for linear mixed-effects modeling, and the package AICcmodavg (Mazerolle 2019) for model selection. The model variances explained by fixed effects (marginal R2) and by both fixed and random effects (conditional R2) are provided (Nakagawa and Schielzeth 2013).

The following parameters were calculated to assess the goodness of the determined chronologies: Mean inter-series correlation (Rbar), to assess agreement between individual series in each fire severity class; expressed population signal (EPS), to determine to what extent the chronologies, which are based on a limited number of trees, were representative of the “hypothetical” true chronologies (Wigley et al. 1984).

For each species, we used a general linear model to analyze the relationship between the δ13C earlywood and δ13C latewood of the current year and between the δ13C earlywood of the current year and the δ13C latewood of the previous years in the pre-burning years (2011–2012–2013) and the post-burning years (2014–2015). We included 2013 as pre-burning years because as spring burns occurred late in the season, we consider that prescribed burning did not impact the earlywood of pines burned in spring. Lastly, to detect time variations in the δ13C latewood, the mean and standard error of δ13C latewood for each species, site and burning season were plotted over time.

Climate-growth relationships were analyzed for each species by calculating Pearson’s correlations between control residual chronologies (total tree-ring, earlywood, and latewood) and P-PET of monthly data, and data of two and three consecutive months using the package TreeClim (Zang and Biondi 2015). The results of this analysis can be found in Annex 2 Figs. 6 and 7.

3 Results

3.1 Tree-ring chronologies

Trees had a similar age within and between chronologies (Table 6 ESM 1). In all chronologies, the EPS had high values (> 0.85), indicating that the chronologies constructed from detrended individuals were representative of the whole tree population (Table 6 ESM 1). The mean BAI for each chronology revealed a similar growth pattern during the entire period (Fig. 1).

Mean and standard error of total tree-ring basal area increment (BAI) for the whole-time span for P. nigra (a and b) and for P. sylvestris (c and d) at Miravé and Lloreda localities for control (black line), spring (green) and fall (brown) plots. Gray shading underlines the year of prescribed burning (2013) and the post-burning period 2014–2015. n = 15 trees per locality, fire treatment and species, except in Lloreda for P. nigra in fall burns (n = 14) and for P. sylvestris in spring burns (n = 12)

3.2 Resistance and resilience of burned and control pines

Resistance was higher in control pines compared with burned pines (Fig. 2a) and in P. sylvestris compared with P. nigra (Table 3), and the species per treatment interaction was not significant. In contrast, resilience was higher in P. nigra than in P. sylvestris independently of burning treatment (Table 3). Total tree-ring and latewood resilience increased in pines burned in the fall compared with control and spring burned pines, as resistance increased (interaction resistance × burning, Table 3 and Fig. 2b).

3.3 Resistance and resilience of burned pines

The resistance of pines burned in fall was lower than that of pines burned in the spring as BSHmin increased (Table 4, Fig. 3a). For pines burned in fall, the interaction between RCI15 and CI12 indicated a positive effect of the release of tree competition (estimated as RCI15), especially in pines with a high pre-burning competition index (CI12) in the total tree-ring and latewood resilience (Table 4 and Fig. 3b for total tree-ring resilience).

Prediction line and partial regression residuals of the models showing for burned pines, the significant interaction in Table 4 between burning season and minimum bole scorch height on resistance (a); and the interactions in Table 4 between the release from tree competition (RCI15) and the pre-burning competition index (CI12) (b) and between the release from tree competition (RCI15) and the minimum bole scorch height (BSHmin) on total-tree ring resilience in 2015 (c)

In agreement with the model that included the control pines (Table 3) resistance had a positive effect on the total tree-ring and latewood resilience of both species (Table 4). Differences between species resilience were mainly found for the latewood resilience and were higher in P. nigra than in P. sylvestris, except in 2015 when the species factor was not significant (Table 4). In 2015, the positive effect of competition release on total tree-ring resilience decreased when individuals experienced higher fire severities (Interaction RCI15 x BSHmin, Table 4; Fig. 3c).

We did not describe the effects of fire severity on spring burns because no differences were detected in the total tree-ring or latewood resilience between pines burned in spring and control pines (Table 3); however, the models can be found in ESM 1 (Table 7).

3.4 Impact of burning season on the post-stress latewood:earlywood

The pre-stress latewood:earlywood of P. sylvestris was significantly lower than that of P. nigra (P < 0.05), without differences between the control and prescribed burning sites.

In P. nigra, the latewood:earlywood was higher after fall burns than after spring burns and in control pines (Table 5). In addition, post-stress latewood:earlywood increased significantly as pre-stress latewood:earlywood decreased (Table 5). In P. sylvestris, neither burning treatment nor pre-stress latewood:earlywood were significant.

3.5 Carbon isotope ratios in P. sylvestris and P. nigra

For 2012 and 2013, in P. nigra, the δ13C of earlywood was related to latewood δ13C of the current year (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.90) (Fig. 4a) but not to the previous δ13C of latewood (Fig. 4b). For 2014 and 2015, the δ13C of earlywood did not significantly correlate with the current or previous δ13C of latewood (data not shown). Considering only latewood, the δ13C of P. nigra tended to be lower in the year of burning and the years after in comparison with pre-burning years, without clear differences between burning seasons (Fig. 4 c and d).

δ13C values in current earlywood (EW (t)) versus current latewood (LW(t)) (a) and in current earlywood (EW (t)) versus previous latewood (LW (t − 1)) (b) for P. nigra and P. sylvestris for pre-burning years 2012 and 2013. The regression for P. sylvestris in b was y = 0.44x - 14.08, R2 = 0.53, n = 8, P < 0.05 and for P. nigra in a was y =1.80x+20.60 , R2 = 0.90, n = 8, P < 0.001). δ13C pool values in current latewood (LW(t)) for P. nigra burned in fall and spring at Lloreda (c) and Mirave (d) sites and for P. sylvestris burned in fall and spring at Lloreda (e) and Mirave (f). The std is showed for the 2011 year (n = 5)

For 2012 and 2013, in P. sylvestris the δ13C of the current earlywood was directly correlated to the latewood δ13C of the previous season (P < 0.05, R2 = 0.53) (Fig. 4b) but not to the latewood δ13C of the current year (Fig. 4a). As in P. nigra, for 2014 and 2015, the earlywood δ13C did not significantly correlate with the current or previous latewood δ13C (data not shown). Considering only latewood, just after burning (2013), at the Lloreda site, the latewood δ13C of P. sylvestris was higher in fall burns than in spring burns (Fig. 4, e). Two years after burning, P. sylvestris burned in fall had lower latewood δ13C than in spring burns at both sites (Fig. 4, e and d).

4 Discussion

4.1 Effects of prescribed burning after a dry year on pine resilience and resistance

Prescribed burns performed the year after a dry year did not reduce pine resilience compared with pines growing in control (unburned) stands. Moreover, individuals’ resilience was positively influenced by resistance and varied between pine species and burning seasons. First, the resilience of those individuals with lower resistance indices was similar in both burned and control pines. This suggests that the impact of burning on drought-stressed individuals in spite of being additive was irrelevant. Second, individuals that resisted drought and burning well showed higher resilience when burning was executed in the fall after the dry year compared with those burned in the spring or left unburned. Two years post-burning, tree mortality was greater in fall burns than in spring burns (Valor et al. 2017). Therefore, the release from tree competition in fall burns may have had a greater positive effect on pine resilience compared with those burned in the spring. The effect of competition release was especially marked in pines with a high pre-burning competition index, suggesting that prescribed burning benefited the growth performance of the more stressed individuals. However, not only was the competition release higher after fall burns, but also the fire damage to the surviving pines. Prolonged heating in fall burns, as indicated by the higher combustion times recorded during fall burns compared with spring burns (Valor et al. 2017), may have caused basal stem girdling and killed small pine roots (Varner et al. 2009). This explains why the effect of competition release was more noticeable in those pines less damaged by burning (low bole scorch height) as well as the lower resistance of fall burned pines compared with spring burned pines. Overall, fire severity after fall burns negatively impacted the resistance of some individuals but enhanced the resilience through the release of competition as time since burning increased.

4.2 Differences in resistance and resilience between species

P. sylvestris had a higher resistance index than P. nigra, which indicates that P. nigra is, unexpectedly, more sensitive to drought and prescribed burning. If resistance and resilience depend on the amount of stored reserves (Galiano et al. 2011; Lloret et al. 2011), then the differences observed between species could reflect a trade-off. Therefore, higher resistance in P. sylvestris would have resulted later in lower resilience while lower resistance in P. nigra would have resulted in higher resilience. Species differences in climate-growth relationships could also explain the unexpected higher resistance of P. sylvestris. The growth of P. nigra showed a stronger correlation with the P-PET of the current year (contrary to Martin-Benito et al. 2013) and thus, growth during the drought year probably reflects the climatic conditions of that year. However, in P. sylvestris the effect of the previous-year climate was more important, and therefore, growth in the drought year was influenced by the favorable conditions of the previous year. The relationship between δ13C in earlywood and current or previous δ13C latewood suggests a tight coupling of wood formation and currently canopy photosynthesis in P. nigra, while wood formation of P. sylvestris seems to rely more on stored carbohydrates from the previous year. In addition, the lower resilience of P. sylvestris compared with P. nigra can be related to the higher sensitivity of P. sylvestris to fire than P. nigra (Fernandes et al. 2008; Valor et al. 2017). Although P. sylvestris was more resistant than P. nigra, the higher latewood δ13C in the year of prescribed burning in fall burns suggests a decrease in stomata conductance due to fire stress. This may have affected the physiology of post-burning pines, which would explain the lower resilience observed in P. sylvestris; however, the loss of resilience could also be attributed to structural changes in the xylem caused by the fire (Bär et al. 2018). Nevertheless, 2 years post-burning there was no difference between P. sylvestris and P. nigra in total tree-ring resilience. This was supported by the more negative values with respect to the pre-burning years of latewood δ13C in P. sylvestris. This probably indicates an improvement in water availability induced by the higher release from tree competition observed in fall burns.

4.3 Effects of burning season on latewood:earlywood

Prescribed burning mainly impacted resilience through its effect on latewood, while earlywood resilience was not clearly affected. In pines with an improved condition due to increased environmental resources caused by burning, a long-lasting differentiation between latewood tracheids in summer and fall months could have occurred. Our findings are similar to those of Linares et al. 2009, who found that the greatest difference between unthinned and intensively thinned treatments in Abies pinsapo was the number of latewood tracheids. Other studies have found crown scorch or releases from tree competition to be possible causes of increases in post-fire latewood (Alfaro-Sánchez et al. 2018; De Micco et al. 2013).

In P. nigra, post-stress latewood:earlywood was higher in pines burned in fall compared with pines burned in spring and control pines. This may be due to the use of available carbohydrates to replenish dead tissues after fall burns, which were more severe than spring burns, rather than for earlywood cells (Cown 1977) and/or to the higher reduction in tree competition after the fall burns that resulted in an increase in latewood.

Recently, Alfaro-Sánchez et al. (2018) found a higher latewood proportion in burned P. halepensis compared with unburned ones at sites with high water availability but not at water-limited sites. The increase in post-stress in the latewood:earlywood compared with control pines, may confer a higher resistance to embolism and provide a minimal hydraulic conductivity at lower water potentials (Mayr and Cochard 2003) as latewood can act as water storage (Domec and Gartner 2002). Moreover, the increase in post-stress latewood:earlywood in P. nigra was higher in those individuals with low pre-stress latewood:earlywood, suggesting that the whole population enhances resistance to upcoming drought events.

5 Conclusions

Prescribed burning after a dry year reduced tree resistance (inverse of growth reduction during disturbance) compared with pines that were only exposed to drought; however, tree resilience (capacity to reach pre-disturbance growth levels) was higher in fall burned pines compared with spring burned pines and control pines. After fall burns, as resistance increased, total tree-ring and latewood resilience was enhanced, especially when pines experienced a release from tree competition.

P. nigra had higher resilience than P. sylvestris. This may be explained by (1) P. sylvestris having higher resistance, suggesting a trade-off between resistance and resilience in terms of tree reserves, (2) P. nigra having higher pre-stress latewood:earlywood, (3) differences in the climate-growth relationship of the species to the same dry year, and 4) P. sylvestris having higher sensitivity to fire compared with P. nigra. For P. nigra, our results suggest that the increase in resource availability induced by prescribed burning increases the proportion of latewood with respect to earlywood, which most likely increases the pines’ resistance to cavitation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Zenodo repository (Valor et al. 2019) at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3520731.

Change history

18 March 2020

The article was originally published with duplicate information appearing in the work.

References

Alfaro-Sánchez R, Camarero JJ, Sánchez-Salguero R, Trouet V, Heras JL (2018) How do droughts and wildfires alter seasonal radial growth in Mediterranean Aleppo pine forests? Tree-Ring Res 74:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3959/1536-1098-74.1.1

Bansal S, Hallsby G, Löfvenius MO, Nilsson MC (2013) Synergistic, additive and antagonistic impacts of drought and herbivory on Pinus sylvestris: leaf, tissue and whole-plant responses and recovery. Tree Physiol 33:451–463. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpt019

Bär A, Nardini A, Mayr S (2018) Post-fire effects in xylem hydraulics of Picea abies, Pinus sylvestris and Fagus sylvatica. New Phytol 217:1484–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14916

Battipaglia G, Strumia S, Esposito A, Giuditta E, Sirignano C, Altieri S, Rutigliano FA (2014) The effects of prescribed burning on Pinus halepensis mill. As revealed by dendrochronological and isotopic analyses. For Ecol Manag 334:201–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.09.010

Battipaglia G, Savi T, Ascoli D, Castagneri D, Esposito A, Mayr S, Nardini A (2016) Effects of prescribed burning on ecophysiological, anatomical and stem hydraulic properties in Pinus pinea L. Tree Physiol 36:1019–1031. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpw034

Biondi F (1999) Comparing tree-ring chronologies and repeated timber inventories as forest monitoring tools. Ecol Appl 9:216–227

Bodig J, Jayne B (1993) Mechanics of wood composites, Reprinted edn. Kreiger Publishing Company, USA

Bottero A, D'Amato AW, Palik BJ, Kern CC, Bradford JB, Scherer SS (2017) Influence of repeated prescribed fire on tree growth and mortality in Pinus resinosa forests, northern Minnesota. For Sci 63:94–100. https://doi.org/10.5849/forsci.16-035

Bunn AG (2008) A dendrochronology program library in R (dplR). Dendrochronologia 26:115–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2008.01.002

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2004) Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Methods Res 33:261–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124104268644

Certini G (2005) Effects of fire on properties of forest soils: a review. Oecologia 143:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1788-8

Collins BM, Das AJ, Battles JJ, Fry DL, Krasnow KD, Stephens SL (2014) Beyond reducing fire hazard: fuel treatment impacts on overstory tree survival. Ecol Appl 24:1879–1886. https://doi.org/10.1890/14-0971.1

Cown DJ (1977) Partial defoliation and wood properties of 5-year-old Pinus radiata. NZ J Forestry Sci 7:192–198

De Micco V, Zalloni E, Balzano A, Battipaglia G (2013) Fire influence on Pinus halepensis: wood responses close and far from the scars. IAWA J 34:446–458. https://doi.org/10.1163/22941932-00000036

Domec JC, Gartner BL (2002) How do water transport and water storage differ in coniferous earlywood and latewood? J Exp Bot 53:2369–2379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erf100

Eilmann B, Buchmann N, Siegwolf R, Saurer M, Cherubini P, Rigling A (2010) Fast response of scots pine to improved water availability reflected in tree-ring width and δ13C. Plant Cell Environ 33:1351–1360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02153.x

FAO I (2006) Working group WRB (2007). World reference base for soil resources

Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT (1989) Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 40:503–537. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443

Fernandes PM, Vega JA, Jiménez E, Rigolot E (2008) Fire resistance of European pines. For Ecol Manag 256:246–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.04.032

Francey R, Allison C, Etheridge D, Trudinger C, Enting I, Leuenberger M, Langenfelds R, Michel E, Steele L (1999) A 1000-year high precision record of δ13C in atmospheric CO2. Tellus B 51:170–193. https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v51i2.16269

Fritts H (1976) Tree rings and climate, 567 pp. Academic, San Diego, Calif

Galiano L, Martinez-Vilalta J, Lloret F (2011) Carbon reserves and canopy defoliation determine the recovery of scots pine 4 yr after a drought episode. New Phytol 190:750–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03628.x

Garcia O (2014) Siplab, a spatial individual-based plant modelling system. Comput Ecol and Softw 4:215–222

Hegyi F (1974) A simulation model for managing jack-pine stands. Growth models for tree and stand simulation 30:74–90

Holling CS (1973) Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 4:1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

Kaufman LH (1982) Stream aufwuchs accumulation: disturbance frequency and stress resistance and resilience. Oecologia 52:57–63

Linares JC, Camarero JJ, Carreira JA (2009) Plastic responses of Abies pinsapo xylogenesis to drought and competition. Tree Physiology 29 (12):1525–1536

Lloret F, Keeling EG, Sala A (2011) Components of tree resilience: effects of successive low-growth episodes in old ponderosa pine forests. Oikos 120:1909–1920. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19372.x

Martin-Benito D, Beeckman H, Canellas I (2013) Influence of drought on tree rings and tracheid features of Pinus nigra and Pinus sylvestris in a Mesic Mediterranean forest. Euro J Forest Res 132:33–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-012-0652-3

Martinez-Meier A, Sanchez L, Pastorino M, Gallo L, Rozenberg P (2008) What is hot in tree rings? The wood density of surviving Douglas-firs to the 2003 drought and heat wave. For Ecol Manag 256:837–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.05.041

Martinez-Vilalta J, Piñol J (2002) Drought-induced mortality and hydraulic architecture in pine populations of the NE Iberian Peninsula. For Ecol Manag 161:247–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(01)00495-9

Mayr S, Cochard H (2003) A new method for vulnerability analysis of small xylem areas reveals that compression wood of Norway spruce has lower hydraulic safety than opposite wood. Plant Cell Environ 26:1365–1371. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0016-8025.2003.01060.x

Mazerolle M (2019) AICcmodavg: model selection and multimodel inference based on (Q)AIC(c). R package version 2:2–2 https://cran.r-project.org/package=AICcmodavg

McCandliss DS (2002) Prescribed burning in the kings river ecosystems project area: lessons learned. In: proceedings of a symposium on the kings river sustainable Forest ecosystems project: progress and current status. USDA Forest Service general technical report PSW-GTR-183, pp. 37-46

Michaletz ST, Johnson E, Tyree M (2012) Moving beyond the cambium necrosis hypothesis of post-fire tree mortality: cavitation and deformation of xylem in forest fires. New Phytol 194:254–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.04021.x

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H (2013) A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol Evol 4:133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00261.x

Niccoli F, Esposito A, Altieri S, Battipaglia G (2019) Fire severity influences ecophysiological responses of Pinus pinaster Ait. Front Plant Sci 10:539. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00539

Ninyerola M, Pons X, Roure JM (2000) A methodological approach of climatological modelling of air temperature and precipitation through GIS techniques. Int J Climatol 20:1823–1841. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0088(20001130)20:14<1823::AID-OC566>3.0.CO;2-B

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, the R Core team DS (2007). nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1–86, https://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme

Sánchez-Costa E, Poyatos R, Sabaté S (2015) Contrasting growth and water use strategies in four co-occurring Mediterranean tree species revealed by concurrent measurements of sap flow and stem diameter variations. Agric For Meteorol 207:24–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2015.03.012

Saurer M, Siegwolf RT, Schweingruber FH (2004) Carbon isotope discrimination indicates improving water-use efficiency of trees in northern Eurasia over the last 100 years. Glob Chang Biol 10:2109–2120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00869.x

Stokes MA, Smiley TL (1968) An introduction to tree-ring dating. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois

Thornthwaite CW (1954) A re-examination of the concept and measurement of potential evapotranspiration. Publications in climatology, vol. VII, 1, Centerton, New Jersey, pp. 200–209

Valor T, Pique M, Lopez BC, Gonzalez-Olabarria JR (2013) Influence of tree size, reduced competition, and climate on the growth response of Pinus nigra Arn. salzmannii after fire. Ann For Sci 70:503–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-013-0284-x

Valor T, González-Olabarria JR, Piqué M, Casals P (2017) The effects of burning season and severity on the mortality over time of Pinus nigra spp. salzmannii (Dunal) Franco and P. sylvestris L. For Ecol Manag 406:172–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2017.08.027

Valor T, Battipaglia G, Piqué M, Altieri S, Gonzalez-Olabarria JR, Casals P. (2019). Data set of resilience indices to drought and prescribed burning of Pinus nigra ssp. salzmannii and P. sylvestris L. trees. Zenodo. [dataset]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3520731

Van der Maaten-Theunissen M, van der Maaten E, Bouriaud O (2015) PointRes: an R package to analyze pointer years and components of resilience. Dendrochronologia 35:34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dendro.2015.05.006

Van Mantgem PJ, Caprio AC, Stephenson NL, Das AJ (2016) Does prescribed fire promote resistance to drought in low elevation forests of the Sierra Nevada, California, USA? Fire Ecol 12:13–25. https://doi.org/10.4996/fireecology.1201013

Van Mantgem PJ, Falk DA, Williams EC, Das AJ, Stephenson NL (2018) Pre-fire drought and competition mediate post-fire conifer mortality in western U.S. National Parks. Ecol Appl 28:1730–1739. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1778

Varner JM, Putz FE, O'Brien JJ, Hiers JK, Mitchell RJ, Gordon DR (2009) Post-fire tree stress and growth following smoldering duff fires. For Ecol Manag 258:2467–2474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.08.028

Wigley TM, Briffa KR, Jones PD (1984) On the average value of correlated time series, with applications in dendroclimatology and hydrometeorology. J Climate App Meteor 23:201–213. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(1984)023<0201:OTAVOC>2.0.CO;2

Wyant JG, Omi PN, Laven RD (1986) Fire induced tree mortality in a Colorado ponderosa pine/Douglas-fir stand. For Sci 32:48–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestscience/32.1.49

Zang C, Biondi F (2015). Treeclim: an R package for the numerical calibration of proxy-climate relationships. Ecography, 38(4), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01335

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank GRAF (Bombers, Generalitat de Catalunya) who kindly executed the PB and the EPAF team, Dani Estruch, Ana I. Ríos, and Alba Mora, for their technical assistance in the field.

Funding

This research was funded by the Life Pinassa Project.

(LIFE13NAT/ES/000724) and by the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (projects, AGL2015–70425-R; EEBB-I-16-11003and BES-2013-065031 to T.V.) and by the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (RTI2018-098778-B-I00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TV and PC conceived the ideas and TV, PC, MP and JG designed methodology; TV and PC collected the data; GB and SA analyzed the isotopic data; TV, PC analyzed data and GB, MP, SA and JG help with the interpretation of the data; TV and PC led the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Paulo Fernandes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The article was originally published with duplicate information appearing in the work. The article has been updated and corrected with the removal of the duplicate material. The original article has been corrected.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 19 kb)

Appendices

Annex 1 Analysis of pointer years

To ascertain that the 2012 event was a year with significant growth reduction in both species we used the package PointRes (van der Maaten-Theunissen et al. 2015). For each tree and year, we calculate the relative growth change (in percentage) (RGC) of a specific year compared with the 3 preceding years in each species. A threshold of 25% was established, below which RGC in a specific tree and a year was considered a negative pointer year or a positive pointer year when the RGC was above 60%. For each year, when more than 50% of all trees within the control chronologies exceed the 25% or 60% threshold, the year was considered a negative or positive pointer year, respectively (Fig. 5).

Annex 2 Growth-climate relationships in P. sylvestris and P. nigra

Climate-growth relationships were analyzed for each species, by calculating Pearson correlations between control residual chronologies (total tree-ring, earlywood, and latewood) and P-PET of monthly data, and data of two and three consecutive months using the package TreeClim (Zang and Biondi 2015).

In P. sylvestris, total tree-ring was positively correlated with accumulated P-PET of previous November and December and current January and with current summer P-PET (June, July and August) (Fig. 6a). Earlywood showed higher positive correlations with P-PET of November–December-January (Fig. 6c) and latewood with the accumulate P-PET of summer months (Fig. 6e). In the 2012 dry year accumulated P-PET in previous November–December and current January, as well as in the summer months, was the lowest respect to the historical values (Fig. 7).

In P. nigra, total tree-ring was significantly correlated with accumulated P-PET of April–May-June and current fall (September, October, and November) (Fig. 6, b). Earlywood was highly correlated with P-PET in April–May–June and latewood with accumulated P-PET in the fall months (Fig. 6, d and f). In the 2012 dry year, accumulated P-PET in April–May–June and fall were lower compared with the historical values (Fig. 7).

Correlation between the TRW index of the residual chronologies of control pines and P-PET of three consecutive months in P. sylvestris for total tree ring (a), earlywood (c), and latewood (d) and in P. nigra for total tree ring (b), earlywood (d), and latewood (f). Months with small letters denote months of the year before tree-ring formation. The correlation showed for a given month includes the two preceding months (e.g., correlation showed in August represents the correlation of June, July and August). Significant coefficients are in dark gray

Precipitation minus Potential Evapotranspiration (P-PET) for the temporal windows that significantly correlated with the growth of P. nigra and P. sylvestris (see Fig. 6) during the period 2011–2015. The mean and standard deviation of P-PET over the entire period (1975–2015) is showed as a reference of historical values. Months with small letters denote months of the year before tree-ring formation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valor, T., Battipaglia, G., Piqué, M. et al. The effect of prescribed burning on the drought resilience of Pinus nigra ssp. salzmannii Dunal (Franco) and P. sylvestris L.. Annals of Forest Science 77, 13 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0912-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0912-1