Abstract

Key message

Permanent sampling plots (PSPs) are a powerful and reliable methodology to help our understanding of the diversity and dynamics of tropical forests. Based on the current inventory of PSPs in Indonesia, there is high potential to establish a long-term collaborative forest monitoring network. Whilst there are challenges to initiating such a network, there are also innumerable benefits to help us understand and better conserve these exceptionally diverse ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Why monitoring tropical forests is important

Tropical forests are arguably the most important terrestrial ecosystems. Whilst occupying around 15% of the global land area, tropical forests store two thirds of all the carbon in terrestrial vegetation (Pan et al. 2013) and are the most important above-ground terrestrial carbon sink (Beer et al. 2010; Pan et al. 2011; Soepadmo 1993). They house half the world’s biodiversity and provide a wide range of goods, including sources of new medicines, and ecosystem services, including clean and sustained water supplies, climate regulation and pollinators for crops (Cámara-Leret et al. 2016; Ghazoul 2015; Peters et al. 1989; Ricketts et al. 2004). If suitably managed, tropical forests can provide economic benefits through ecotourism, non-timber forest products, a sustainable source of timber, and through carbon financing mechanisms for developing tropical countries such as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+). Therefore, understanding where, how and why the world’s tropical forests are changing is a key question of global importance (Hansen et al. 2013; Pan et al. 2011).

The periods over which trees establish, grow and die (tens to hundreds of years) do not make for rapid experimental tests of forest functioning. Instead, direct measurements of stands of trees over long time periods are essential to truly understand forest processes and dynamics (Lutz 2015). Permanent sample plots (PSPs) in which all trees are marked, identified and repeatedly measured provide a series of direct observations on forest condition, dynamics and change over time. As longitudinal data sets, PSPs offer an excellent opportunity to study forest dynamics and to separate short-term environmental impacts, such as drought, from long-term trends (Condit 1998). A forest monitoring network is a series of PSPs using a consistent protocol—such networks allow an assessment of numerous aspects of forest ecology, including biodiversity, biomass (analogous to carbon stocks), regeneration, dynamics (including succession) and ‘health’. Furthermore, forest monitoring networks distributed along large geographical and environmental gradients allow testing for the generality of factors controlling ecosystem functioning with increased statistical power (Craine et al. 2007) and allow space-for-time analyses to project potential impacts of global changes on forests.

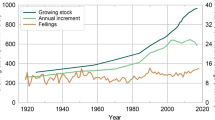

Numerous high-impact studies based on PSPs as the fundamental measurement unit have greatly advanced our understanding of the function, biodiversity and evolution of tropical forests. For example, PSPs have provided clear evidence that the tropical forest above-ground carbon stock has been increasing over time (Lewis et al. 2009; Pan et al. 2011; Qie et al. 2017) but that the sink strength into this stock appears to be declining, at least in Amazonia (Brienen et al. 2015). The above studies were conducted in ‘undisturbed’, i.e. primary, forests but a major proportion of tropical forests have been disturbed by human activities. Fewer PSP networks have been established to study forest recovery from logging (Rutishauser et al. 2015; Sist et al. 2014) or from shifting cultivation (Chazdon et al. 2016) yet they are also providing valuable data. Furthermore, PSPs contribute vital datasets to improve our still poor understanding of patterns in tropical tree species richness (Slik et al. 2015; ter Steege et al. 2013), biogeography (Slik et al. 2018) and evolution (Baker et al. 2014) at multiple scales. Field data collected on the ground from biogeographically well-replicated PSPs are also a prerequisite to calibrate remotely sensed biomass mapping (e.g. Asner et al. 2010; Avitabile et al. 2016; Réjou-Méchain et al. 2014).

Permanent sample plots are a standard method but can be supplemented by biodiversity observation networks such as the transect approach of the Asia-Pacific Biodiversity Observation Network (Yahara et al. 2012, 2014). Larger PSPs (~ 50 ha), such as those established by the Centre for Tropical Forest Science (CTFS, now ForestGEO), play an important role in furthering our understanding of community ecological patterns as they monitor a larger number of smaller (≥ 1 cm dbh) trees over bigger areas. In contrast, smaller PSPs (usually 1 ha), such as those established by the Amazon Forest Inventory Network (RAINFOR) and the Indonesian National Forest Inventory (see Section 2), offer extensive coverage that is more appropriate for a regional-scale forest monitoring network.

2 Opportunities from permanent sample plots in Indonesia

Indonesia has the third largest area of tropical forest globally (following Brazil and D.R. Congo; FAO 2015) including some of the largest extents of carbon-dense peat swamp forests. However, as with other regions of the world, Indonesia’s forests are undergoing rapid change and anthropogenic disturbance (Abood et al. 2014; Gaveau et al. 2014) and around half the country’s land area currently supports primary forest (Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan 2015b; Margono et al. 2014). The forests of western Indonesia are highly productive and the dominant trees, the dipterocarps (Brearley et al. 2016), have been favoured as commercial timber trees for many years leading to the majority of accessible forests being brought into timber production. By contrast, the forests of eastern Indonesia (especially Papua) contain few dipterocarps and remain more intact owing to the rugged topography and isolation. More recent challenges include droughts and fires associated with El Niño that have had marked impacts upon forest functioning (Page & Hooijer 2016; Slik 2004) and increasing forest fragmentation (Qie et al. 2017), yet large-scale analyses that test for such impacts across Indonesian forests are largely absent.

Numerous PSPs have been established across Indonesia over the last c. 60 years but not all have been maintained continuously. The earliest PSPs were established during the late Dutch colonial era, but they were mostly in plantation forests to study tree growth and timber yield (Hart 1928; Von Wulfing 1938). Among the first PSPs established in primary forest was the 1-ha plot set-up by Willem Meijer (1959) to study the ecology of Gunung Gede’s montane forests. Since then, PSPs have played an important role in silvicultural research such as the STREK (Silvicultural Techniques for the Regeneration of Logged-over Forest in East Kalimantan) project (Bertault & Kadir 1998).

The Indonesian National Forest Inventory (NFI) is a national program initiated by the Indonesia Ministry of Forestry in 1989 (and implemented by the Directorate General of Forestry Planning) utilising PSPs. Through this program, PSPs were established systematically with a 20 × 20 km grid across forested areas in Indonesia (< 1000 m above sea level) with the primary objective to monitor the growth of timber stocks. In total, 2735 1-ha PSPs were established, although not all have been monitored on more than one occasion (Kementerian Kehutanan 1996). Depending on the location, the NFI plots were not necessarily located in logging concessions but all logging companies were required to establish PSPs for monitoring growth and yield. In addition to monitoring timber growth and yield, data from these PSPs has provided a basis for estimating carbon stocks and changes associated with land-use change and forest management activities (Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan 2016; Krisnawati et al. 2014, 2015).

Despite the large-scale coverage of Indonesia’s NFI, the limited scientific access NFI offers to its data and the few large-scale analyses that have resulted from the NFI’s dataset limit our understanding of the composition and functioning of Indonesia’s tropical forests. Given the current threats to Indonesia’s forests, it is important that Indonesian and foreign scientists collaborate, with a consolidated scientist-led forest monitoring network having the flexibility to address ecological questions in a democratised and collaborative fashion, to jointly establish PSPs and analyse large datasets spanning Indonesia’s forests. To date, at least 150 ha of PSPs (besides those in the NFI) have been established in primary forest and are still maintained, in Indonesia (Table 1; Figs. 1a and 2). Although these PSPs have different sizes, re-measurement intervals and measurement protocols making direct comparisons challenging, they offer a starting point for developing an Indonesian forest monitoring network with a standardised protocol. The density of sampling across the whole of Indonesia is only about 3.4 ha of plots per 106 ha of primary forest, and there are clear differences in sampling density between different geographical regions (Table 1). The highest density (ratio of the plot area to primary forest area) of PSPs, by an order of magnitude, is found in Java and Bali (Table 1). Although the total area of PSPs is modest, the area of primary forest remaining is particularly low on these islands leading to an overall very high sampling density. Of the outer islands, Kalimantan has a high density of sampling—likely due to this being the centre of production forest logging activity coupled with an interest in its exceptional biodiversity since the times of early colonial explorers. Sumatra has a similar sampling density and has also been heavily exploited for timber in the past. Maluku also has a high sampling density but this is largely confined to Seram only. Sulawesi and Nusa Tenggara have sampling densities comparable to the mean for the whole of Indonesia (although note that there is only 2.5 ha of plots in Nusa Tenggara). Sampling density for Papua is, by far, the lowest among the Indonesian islands; this is partly due to the large remaining area of the forest combined with difficulties in establishing PSPs in areas with challenging access. Of these PSPs, nearly half have been measured on more than one occasion, thereby markedly increasing their value for assessing forest functioning, with the median monitoring period for those measured more than once being 8 years and the longest being 50 years (Fig. 2b). About half of the plots that have been measured on more than one occasion are in Kalimantan (e.g. Qie et al. 2017) so the total monitoring effort (plot area × monitoring length) at around 1300 ha years is an order of magnitude greater than Java + Bali, Maluku, Sulawesi or Sumatra; none of the PSPs in Nusa Tenggara or Papua have been re-measured (Fig. 2c). In addition, there are over 100 ha of PSPs in disturbed forest (Fig. 1b); many of these are forests that have been logged. In this case, the geographical foci are Kalimantan and Sumatra that have historically been important for timber and, secondarily, in Papua where logging activities are currently expanding.

a Plot areas, b total plot area under different lengths of monitoring and c total monitoring effort (i.e. sum of area multiplied by monitoring length for each plot) for permanent sample plots (PSPs) in primary forest (excluding the National Forest Inventory) on major islands of Indonesia. For panel (c), note that plots only measured once are given a monitoring length of 1 year and also note the logarithmic scale

From the brief analysis above, it is clear that key geographical gaps exist mainly in eastern Indonesia particularly for Maluku (excepting Seram), Nusa Tenggara and Papua. In terms of climate, many areas of drier forest are under-represented (e.g. Timor), as is montane forest and forest over edaphic variants (such as kerangas or ultramafic geology). There are some PSPs found in peat swamp forests but many have been burnt or otherwise disturbed in recent years.

3 Challenges facing an Indonesian forest monitoring network

3.1 Methods

Our aim here is not to provide a protocol or critique of methods for PSPs as this has been done in previous work (Alder & Synott 1992; Burslem & Ledo 2015; Condit 1998; Ledo 2015; Phillips et al. 2016; Sheil 1995) but to note concerns with particular relevance to the Indonesian situation.

Plot size

Too many PSPs reported in the Indonesian literature are simply too small to provide a generalisation of the area they study. Small plots (e.g. 0.04 ha) might be useful when installed in a series (e.g. 25) to provide data on forest biodiversity that does not require accurate scaling up to larger areas. However, for a more in-depth assessment of forest biodiversity, the larger the area sampled, the greater the number of species captured due to a large number of rare species (Plotkin et al. 2000). Of the PSPs noted in our analysis, the median size is 0.25 ha whilst the most frequently sized plot is 1 ha (Fig. 2a), which is comparable to forest monitoring networks on other continents (Brienen et al. 2015; Lewis et al. 2009; Phillips et al. 2009, 2016). Small plots cannot accurately predict forest biomass when scaled up to a larger area due to a high edge to interior ratio that elevates the relative importance of marginal boundary decisions (Burslem & Ledo 2015), a high coefficient of variation between plots and the likelihood they will not represent all forest stages (e.g. gap, building and mature, sensu Whitmore 1998). Calibration of remote sensing data for large-scale forest biomass mapping is more accurate if the PSPs can be ground-truthed accurately, which also requires larger plots (Avitabile et al. 2016; Réjou-Méchain et al. 2014). Finally, small plots are also prone to the ‘majestic effect’ where researchers may unconsciously select pristine forest with ‘majestic’ large trees and avoid disturbed areas (Sheil 1995).

Frequency of measurement

Whilst the definition of a PSP is that trees will be re-measured at some point in time, re-measurement intervals are not always regular. A typical re-measurement interval is 5 years as this allows increases in tree size to be seen more easily. Whilst intervals of 4 to 10 years are appropriate for most recording purposes of PSPs (Sheil 1995), an increasing census period leads to a greater likelihood of unobserved growth and therefore an underestimation of forest productivity (Talbot et al. 2014). In cases of annual censuses, this will allow much better predictions of forest dynamics in relation to annual climate fluctuations (Clark et al. 2010). Dendrometer bands are a possible inexpensive alternative to increase measurement frequency (Anemaet & Middleton 2013), but require much greater time investment at installation; such bands can also avoid errors due to changes of the point of measurement. Of course, the regularity of re-measurement depends upon plot security and accessibility, and funding is a key determinant of the frequency of fieldwork activities (see Section 3.3).

Parameters measured

Trunk diameter at breast height (usually 1.3 m) is the key parameter measured as this can be incorporated into allometric equations to estimate tree and stand biomass (Chave et al. 2014); including tree height and crown, size has been shown to increase the accuracy of such equations (Goodman et al. 2014). This is especially needed for dipterocarps that show different architectural patterns compared to other tropical trees (i.e. taller for a given diameter: Banin et al. 2012). Forests in Indonesia cover not only a wide range of soil and climatic types both within and across islands, but also represent a great biogeographical range. Due to variable architectures that require local height-diameter models for accurate biomass calculation, tree height data collected within plots are extremely useful to improve biomass estimates (Ledo et al. 2016; Sullivan et al. 2018).

3.2 Taxonomy

For assessment of species distributions and monitoring, accurate taxonomy, comparable among plots, is paramount. Good taxonomy is clearly challenging as PSPs often contain a large proportion of sterile individuals. Indonesia is fortunate in having a large and well-maintained national herbarium (Herbarium Bogoriense; BO) and a number of regional herbaria but many PSP investigators do not routinely collect voucher specimens but rely on vernacular names instead. Taxonomy takes on extra importance in a forest monitoring network where the aim is to make comparisons among plots, but technological advances have a key role to play here (Baker et al. 2017; Webb et al. 2010). Whilst some Indonesian tree genera are reasonably well known, for example, the commercially important dipterocarps (Ashton 2004) many large genera such as Syzygium (Myrtaceae) and Diospyros (Ebenaceae) have not been monographed. Similarly, digitization of herbarium sheets at BO is ongoing but progress remains slow.

Vouchers for morphotypes can be made available across sites permitting analysis of the distribution of taxa without any formal species names, but obtaining the species name increases the value of the voucher. Challenges for the taxonomy of PSP trees must be taken seriously, and we recommend the following: (i) make physical voucher collections of several specimens for each morphotype especially where variation appears to be high and collect silica gel-dried samples for subsequent DNA barcoding, (ii) carry out routine visits to PSPs to collect fertile specimens as they become available, (iii) take high-quality photographs of the fresh vouchers (Webb et al. 2010) and share images and metadata online, (iv) cross-match vouchers and images across different sites to both validate formal species name and provide distribution information, (v) avoid the use of vernacular names, except as an early step in the determination process yet value the experience of parataxonomists in the field and technicians in herbaria and (vi) publish details of how taxon names were acquired, and give a level of confidence in each formal name. Overall, it is far more useful to publish voucher collection codes, images, morphotype codes and matches of morphotypes to images at other sites than to simply list a botanical name with no additional information. Detailed primary data will also greatly assist taxonomic specialists in the future as they work on the large, complex genera of Indonesian trees.

3.3 Funding

Funding presents a perennial challenge for forest ecological work, particularly in developing countries. Within Indonesia, PSP censuses are not considered as applied research, which receives priority for funding, although NFI plots have been allocated governmental funding. Current funding opportunities through the development of the Indonesian Science Fund (DIPI) and via the UK Newton Fund are positive in this regard. There is also the potential for knowledge-exchange partnerships with logging companies who may fund PSPs in their concessions although, as funders, they may consider themselves data owners (see Section 3.4). REDD+ programmes bring similar opportunities for knowledge exchange and funding (Gibbs et al. 2007). Longer-term collaborations between Indonesian researchers, companies and NGOs coupled with leading international expertise are needed. Importantly, PSPs need to be locally owned, and international funding should be invested for pump-priming and capacity building in order to stimulate long-term funding input from Indonesian sources into tropical forest monitoring.

3.4 Data sharing

Developing an integrated picture on changes in forest functioning and biodiversity across a forest monitoring network requires the willingness to share data among researchers. Nevertheless, data sharing can present various challenges. There are a number of data sharing models in tropical ecology, ranging from the informal to the formal with rigid data sharing arrangements such as ForestPlots (López-González et al. 2011). What is shared can vary from whole plot data to only the numbers required for a particular analysis. Issues over intellectual property are of considerable concern and unwillingness to share data is often linked to concerns about the loss of control over such data and the lack of professional recognition or reward (Enke et al. 2012; Fecher et al. 2015). Furthermore, clarifying who is the ‘owner’ of data is essential. In some cases, the funder (often a logging company) may claim ownership, in others, such as the Indonesian NFI, public access to the data is limited. Any forest monitoring network needs clear guidelines on the sharing, use and publication of shared data and an obvious reward system for sharing (i.e. co-authorship).

Although in-country data owners will regularly be included as co-authors in large-scale data analyses, the lead authors have almost always been researchers from extra-tropical countries. Echoing the sentiments of Ruslandi et al. (2014), we note that simply ‘out-sourcing’ data analysis to extra-tropical researchers is still far from the goal of building local research capacity. Lack of institutional support and incentive may deter tropical scientists from becoming leading authors, but this appears to be changing lately with Indonesian institutions increasingly rewarding staff publishing in international journals. Investing in capacity-building and knowledge exchange to support Indonesian scientists to take leadership roles in agenda setting is also important in the medium term.

3.5 Land tenure and community engagement

Once a series of PSPs has been established, it is important to maintain a commitment to re-measure plots and obtain funding to do so. However, the location and accessibility of plots need to be considered for long-term measurements. Ideally, plot locations should not be too remote to make accessibility challenging and not too close to settlements put plots at risk from disturbances. If new PSPs are installed, there should be secure land tenure (Soraya 2011) to offer protection from land-use change and fire risk—particularly in peat swamp forests (Page & Hooijer 2016). Of the PSPs noted (Table 1; Figs. 1 and 2), less than half are within formally protected areas (e.g. National Parks or Nature Reserves); of those that are not, the presence of researchers may help in protecting them to some degree (Laurance 2013). In areas where forest land use classifications may jeopardise studies, it may be possible to re-designate land classifications (e.g. Kawasan Hutan Dengan Tujuan Khusus or ‘Special Use Forests’). Local stakeholder engagement is key, and local communities should be considered as valuable collaborators who value the presence of PSPs and can be employed to collect good quality data (Theilade et al. 2015). There are multiple opportunities for synergies between local communities, logging companies and scientists, with NGOs often in a strong position to act as facilitators. Still, unless direct payments to forest owners are established for missed opportunities of economic development, communities may well continue to prefer the economic benefits offered by logging companies over those from researchers or conservationists (Novotny 2010).

4 Translating results from PSPs to forest policy and conservation

Quantification and assessment of carbon stocks in forests underpins international policies to mitigate carbon dioxide emissions such as the REDD+ program (Gibbs et al. 2007) and the recommendations of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Watson et al. 2000). For example, Indonesia’s forest reference emission level submitted to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan 2015a, refined in 2016) utilised NFI data as the primary source to generate information on carbon stocks (and thus emissions from forest change).

It is essential to understand not only carbon stocks in tropical forests through time but also the response of tropical forest to climate change and develop policies accordingly. Information from PSPs will allow us to determine whether Indonesian forests are sinks or sources of carbon and have the potential to help us understand the factors driving carbon stock changes. To derive national policies, information from PSPs needs to be combined with data on land use and land-use change, which is accessible through remote sensing data or national inventories.

In addition, tropical forests are also key repositories of global biodiversity, genetic resources and important ecosystem services for local communities. Reducing biodiversity loss is a target of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (Pereira et al. 2013) which is not only relevant from an aesthetic point of view, but can also threaten ecosystem functioning (Duffy 2009). Permanent sample plot data will foster a better understanding of the autecology, distribution and rarity of tree species and they also have the potential to obtain measures of biodiversity of various taxonomic groups at multiple scales and to link the abundances of each of these with one another. All of the above are needed to enhance Indonesia’s conservation planning efforts and manage forests in a way that allows biodiversity to flourish in this exceptionally diverse country.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- NFI:

-

(Indonesian) National Forest Inventory

- PSP:

-

Permanent sampling plot

- REDD+:

-

Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation

References

Abood SA, Lee JSH, Burivalova Z, Garcia-Ulloa J, Koh LP (2014) Relative contributions of the logging, fiber, oil palm, and mining industries to forest loss in Indonesia. Conserv Lett 8:58–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12103

Alder D, Synott TJ (1992) Permanent sample plot techniques for mixed tropical forest, tropical forestry papers 25. Oxford Forestry Institute, Oxford

Anemaet ER, Middleton BA (2013) Dendrometer bands made easy: using modified cable ties to measure incremental growth of trees. Appl Plant Sci 1:1300044. https://doi.org/10.3732/apps.1300044

Ashton PS (2004) Dipterocarpaceae. In: Soepadmo E, Saw LG, Chung RCK (eds) Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak, vol 5. Forest Research Institute of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, pp 63–388

Asner GP, Powell GPN, Mascaro J, Knapp DE, Clark JK, Jacobson J, Kennedy-Bowdoin T, Balaji A, Paez-Acosta G, Victoria E, Secada L, Valqui M, Hughes RF (2010) High-resolution forest carbon stocks and emissions in the Amazon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:16738–16742. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004875107

Avitabile V, Herold M, Heuvelink GBM et al (2016) An integrated pan-tropical biomass map using multiple reference datasets. Glob Change Biol 22:1406–1420. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13139

Baker TR, Pennington RT, Magallon S et al (2014) Fast demographic rates promote high diversification rates of Amazonian trees. Ecol Lett 17:527–536. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12252

Baker TR, Pennington RT, Dexter KG, Fine PVA, Fortune-Hopkins H, Honorio EN, Huamantupa-Chuquimaco I, Klitgård BB, Lewis GP, de Lima HC, Ashton PS, Baraloto C, Davies SJ, Donoghue MJ, Kaye M, Kress WJ, Lehmann CER, Monteagudo A, Phillips OL, Vásquez R (2017) Maximising synergy among tropical plant systematists, ecologists, and evolutionary biologists. Trends Ecol Evol 32:258–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.01.007

Banin L, Feldpausch TR, Phillips OL et al (2012) What controls forest architecture? Testing environmental, structural and floristic drivers. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 21:1179–1190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2012.00778.x

Beer C, Reichstein M, Tomelleri E, Ciais P, Jung M, Carvalhais N, Rödenbeck C, Arain MA, Baldocchi D, Bonan GB, Bondeau A, Cescatti A, Lasslop G, Lindroth A, Lomas M, Luyssaert S, Margolis H, Oleson KW, Roupsard O, Veenendaal E, Viovy N, Williams C, Woodward FI, Papale D (2010) Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: global distribution and covariation with climate. Science 329:834–838. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1184984

Bertault J-G, Kadir K (1998) Silvicultural research in a lowland mixed dipterocarp forest of East Kalimantan: the contribution of STREK project. CIRAD-forêt, Ministry of Forestry Research and Development Agency (FORDA) & P.T. Inhutani 1, Montpellier, France & Jakarta, Indonesia

Brearley FQ, Banin LF, Saner P (2016) Ecology of the Asian dipterocarps. Plant Ecol Divers 9:429–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/17550874.2017.1285363

Brienen RJW, Phillips OL, Feldpausch TR et al (2015) Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 519:344–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14283

Burslem DFRP, Ledo A (2015) High carbon stock consulting study 1: review of forest inventory methods for estimating biomass carbon stocks. Available online: http://www.simedarby.com/sustainability/clients/simedarby_sustainability/assets/contentMS/img/template/editor/HCSReports/Consulting%20Report%201_Review%20of%20forest%20inventory%20methods%20for%20estimating%20biomass%20carbon%20stocks.pdf (Accessed on 26 September 2017)

Cámara-Leret R, Faurby S, Macía MJ, Balslev H, Göldel B, Svenning J-C, Kissling WD, Rønsted N, Saslis-Lagoudakis CH (2016) Fundamental species traits explain provisioning services of tropical American palms. Nat Plants 3:16220. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2016.220

Chave J, Réjou-Méchain M, Búrquez A et al (2014) Improved allometric models to estimate the aboveground biomass of tropical trees. Glob Change Biol 20:3177–3190. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12629

Chazdon RL, Broadbent EN, Rozendaal DMA et al (2016) Carbon sequestration potential of second-growth forest regeneration in the Latin American tropics. Sci Adv 2:e1501639. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501639

Clark DB, Clark DA, Oberbauer SF (2010) Annual wood production in a tropical rain forest in NE Costa Rica linked to climatic variation but not to increasing CO2. Glob Change Biol 16:747–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02004.x

Condit R (1998) Tropical Forest Census Plots. Springer, Berlin

Craine JM, Battersby J, Elmore AJ, Jones AJ (2007) Building EDENs: the rise of environmentally distributed ecological networks. BioScience 57:45–54. https://doi.org/10.1641/B570108

Duffy JE (2009) Why biodiversity is important to the functioning of real-world ecosystems. Front Ecol Environ 7:437–444. https://doi.org/10.1890/070195

Enke N, Thessen A, Bach K, Bendix J, Seeger B, Gemeinholzer B (2012) The user’s view on biodiversity data sharing—investigating facts of acceptance and requirements to realize a sustainable use of research data. Ecol Inform 11:25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.03.004

FAO (2015) Global forest resources assessment 2015. Food and agriculture organisation of the United Nations, Rome, Italy

Fecher B, Friesike S, Hebing M (2015) What drives academic data sharing? PLoS One 10:e0118053. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118053

Gaveau DLA, Sloan S, Molidena E, Yaen H, Sheil D, Abram NK, Ancrenaz M, Nasi R, Quinones M, Wielaard N, Meijaard E (2014) Four decades of forest persistence, clearance and logging on Borneo. PLoS One 9:e101654. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101654

Ghazoul J (2015) Forests: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Gibbs HK, Brown S, Niles JO, Foley JA (2007) Monitoring and estimating tropical forest carbon stocks: making REDD a reality. Environ Res Lett 2:045023. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/2/4/045023

Goodman RC, Phillips OL, Baker TR (2014) The importance of crown dimensions to improve tropical tree biomass estimates. Ecol Appl 24:680–698. https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0070.1

Hansen MC, Potapov PV, Moore R, Hancher M, Turubanova SA, Tyukavina A, Thau D, Stehman SV, Goetz SJ, Loveland TR, Kommareddy A, Egorov A, Chini L, Justice CO, Townshend JRG (2013) High-resolution global maps of 21st-century global forest cover change. Science 342:850–853. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244693

Hart HMJ (1928) Stamtal en Dunning: Een Oriënteerend Onderzoek Naar de Beste Plantwijdte en Dunningswijze Voor den Djati. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië, Batavia, Nederlandsch-Indië

Kementerian Kehutanan (1996) National Forest Inventory of Indonesia: Final Forest Resources Statistics Report, Field Document 55, UTF/INS/066/INS. Directorate General of Forest Inventory and land use planning, Ministry of Forestry. Indonesia & Food and agriculture organisation of the united nations. Jakarta, Indonesia

Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan (2015a) National Forest Reference Emission Level for REDD+: In the Context of Decision 1/CP.16 Paragraph 70. Directorate General of Climate Change, Ministry of Environment and Forestry: Jakarta, Indonesia

Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan (2015b) Statistik Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan Tahun 2014. Ministry of Environment and Forestry. Jakarta, Indonesia

Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan (2016) National Forest Reference Emission Level for Deforestation and Forest Degradation: In the Context of Decision 1/CP.16 para 70 UNFCCC (Encourages developing country parties to contribute to mitigation actions in the forest sector). Directorate General of Climate Change, Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Jakarta, Indonesia

Krisnawati H, Adinugroho WC, Imanuddin R, Hutabarat S (2014) Estimation of forest biomass for quantifying CO2 emissions in Central Kalimantan: a comprehensive approach in determining forest carbon emission factors. Research and Development Center for Conservation and Rehabilitation, Forestry Research and Development Agency of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Bogor, Indonesia

Krisnawati H, Imanuddin R, Adinugroho WC, Hutabarat S (2015) Standard methods for estimating greenhouse gas emissions from the forestry sector in Indonesia (version 1). Research and Development Center for Conservation and Rehabilitation, Forestry Research and Development Agency of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Bogor, Indonesia

Laurance WF (2013) Does research help to safeguard protected areas? Trends Ecol Evol 28:261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2013.01.017

Ledo A (2015) Protocol for inventory of mapped plots in tropical forest. J Trop For Sci 27:240–247

Ledo A, Cornulier T, Illian JB, Iida Y, Kassim AR, Burslem DFRP (2016) Re-evaluation of individual diameter:height allometric models to improve biomass estimation of tropical trees. Ecol Appl 26:2376–2382. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1450

Lewis SL, López-González G, Sonké B et al (2009) Increasing carbon storage in intact African tropical forests. Nature 457:1003–1006. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07771

López-González G, Lewis SL, Burkitt M, Phillips OL (2011) ForestPlots.net: a web application and research tool to manage and analyse tropical forest plot data. J Veg Sci 22:610–613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01312.x

Lutz JA (2015) The evolution of long-term data for forestry: large temperate research plots in an era of global change. Northwest Sci 89:255–269. https://doi.org/10.3955/046.089.0306

Margono BA, Potapov PV, Turubanova S, Stolle F, Hansen MC (2014) Primary forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000-2012. Nat Clim Chang 4:730–735. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2277

Meijer W (1959) Plantsociological analysis of montane rainforest near Tjibodas, West Java. Acta Bot Neerl 8:277–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.1959.tb00540.x

Novotny V (2010) Rain forest conservation in a tribal world: why forest dwellers prefer loggers to conservationists. Biotropica 42:546–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7429.2010.00658.x

Page SE, Hooijer A (2016) In the line of fire: the peatlands of South-east Asia. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 371:20150176. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0176

Pan Y, Birdsey RA, Fang J, Houghton R, Kauppi PE, Kurz WA, Phillips OL, Shvidenko A, Lewis SL, Canadell JG, Ciais P, Jackson RB, Pacala SW, McGuire AD, Piao S, Rautiainen A, Sitch S, Hayes DA (2011) A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 333:988–993. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201609

Pan Y, Birdsey RA, Phillips OL, Jackson RB (2013) The structure, distribution, and biomass of the world’s forests. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 44:593–622. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135914

Pereira HM, Ferrier S, Walters M et al (2013) Essential biodiversity variables. Science 339:277–278. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1229931

Peters CM, Gentry AH, Mendelsohn RO (1989) Valuation of an Amazonian rainforest. Nature 339:655–656. https://doi.org/10.1038/339655a0

Phillips OL, Aragão LEOC, Lewis SL et al (2009) Drought sensitivity of the Amazon rainforest. Science 323:1344–1347. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164033

Phillips OL, Baker TR, Feldpausch TR, et al (2016) RAINFOR field manual for plot establishment and remeasurement. [http://www.rainfor.org/upload/ManualsEnglish/RAINFOR_field_manual_version_2016.pdf] Accessed 6 September 2017

Plotkin JB, Potts MD, Yu DW, Bunyavejchewin S, Condit R, Foster R, Hubbell SP, LaFrankie J, Manokaran N, Lee H-S, Sukumar R, Nowak MA, Ashton PS (2000) Predicting species diversity in tropical forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:10850–10854. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.20.10850

Qie L, Lewis SL, Sullivan MJP et al (2017) Long-term carbon sink in Borneo’s forests, halted by drought and vulnerable to edge effects. Nat Commun 8:1966. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01997-0

Réjou-Méchain M, Muller-Landau HC, Detto M et al (2014) Local spatial structure of forest biomass and its consequences for remote sensing of carbon stocks. Biogeosciences 11:6827–6840. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-6827-2014

Ricketts TH, Daily GC, Ehrlich PR, Mitchener CD (2004) Economic value of tropical forests for coffee pollination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:12579–12582. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0405147101

Ruslandi RA, Sist P, Peña-Claros M, Thomas R, Putz FE (2014) Beyond equitable data sharing to improve tropical forest management. Int For Rev 16:497–503. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554814813484112

Rutishauser E, Hérault B, Baraloto C et al (2015) Rapid tree carbon stock recovery in managed Amazonian forests. Curr Biol 25:R787–R788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.034

Sheil D (1995) A critique of permanent plot methods and analysis with examples from Budongo Forest, Uganda. For Ecol Manag 77:11–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-1127(95)03583-V

Sist P, Rutishauser E, Peña-Claros M et al (2014) The tropical managed forests observatory: a research network addressing the future of tropical logged forests. Appl Veg Sci 18:171–174. https://doi.org/10.1111/avsc.12125

Slik JWF (2004) El Niño droughts and their effects on tree species composition and diversity in tropical rain forests. Oecologia 141:114–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1635-y

Slik JWF, Arroyo-Rodríguez V, Aiba S-I et al (2015) An estimate of the number of tropical tree species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:7472–7477. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1423147112

Slik JWF, Franklin J, Arroyo-Rodríguez V et al (2018) Phylogenetic classification of the world’s tropical forests. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:1837–1842. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714977115

Soepadmo E (1993) Tropical rain forests as carbon sinks. Chemosphere 27:1025–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-6535(93)90066-E

Soraya E (2011) Enhancing permanent sample plot system in Indonesian forest resource management. Poster presented at First International Conference of Indonesian Forestry Researchers (INAFOR) Bogor, 5–7 December 2011. Available online: http://www.forda-mof.org/files/Poster1-10-INAFOR_2011.pdf. (Accessed 16 December 2016)

Sullivan MJP, Lewis SL, Hubau W et al (2018) Field methods for sampling tree height for tropical forest biomass estimation. Methods Ecol Evol 9:1179–1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12962

Talbot J, Lewis SL, López-González G et al (2014) Methods to estimate aboveground wood productivity from long-term forest inventory plots. For Ecol Manag 320:30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.02.021

ter Steege H, Pitman NCA, Sabatier D et al (2013) Hyperdominance in the Amazonian tree flora. Science 342:1243092. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1243092

Theilade I, Rutishauser E, Poulsen MK (2015) Community assessment of tropical tree biomass: challenges and opportunities for REDD+. Carbon Balance Manag 10:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-015-0028-3

Von Wulfing HEW (1938) Opstandstafels voor djatiplantsoenen. Tectona 31:562–579

Watson RT, Noble IR, Bolin B, Ravindranath NH, Verardo DJ, Dokken DJ (2000) Land use, land-use change and forestry. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Webb CO, Slik JWF, Triono T (2010) Biodiversity inventory and informatics in Southeast Asia. Biodivers Conserv 19:955–972. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-010-9817-x

Whitmore TC (1998) An introduction to tropical rain forests. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Yahara T, Akasaka M, Hirayama H, Ichihashi R, Tagane S, Toyama H, Tsujino R (2012) Strategies to observe and assess changes of terrestrial biodiversity in the Asia-Pacific regions. In: S-i N, Yahara T, Nakashizuka T (eds) The biodiversity observation network in the Asia-Pacific region: toward further development of monitoring. Springer, Tokyo, pp 3–20

Yahara T, Ma K, Darnaedi D, Miyashita T, Takenaka A, Tachida H, Nakashizuka T, Kim E-S, Takamura N, S-i N, Shirayama Y, Yamamoto H, Vergara SG (2014) Developing a regional network of biodiversity observation in the Asia-Pacific region: achievement and challenges of AP BON. In: S-i N, Yahara T, Nakashizuka T (eds) Asia-Pacific biodiversity observation network: integrative observations and assessments. Springer, Tokyo, pp 3–28

Acknowledgments

We thank the British Council for the Researcher Links Workshop grant (through the UK Newton Fund) that brought most of the authors to an initial workshop in Bogor, Indonesia, in September 2016 and all our colleagues who kindly provided information on their PSPs throughout Indonesia.

Funding

This work was funded by the British Council through the UK Newton Fund. The funders had no role in the completion of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Erwin Dreyer

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contribution of the co-authors

FQB and HG obtained funding, FQB and APT organised the workshop and FQB led the workshop. FQB led the writing of the manuscript with major input from WCA, RC-L, HK, AL, LQ and COW and minor input from FG, SO, SRP, P, AHR, ES, TELS, S, HLT, LAT, TT and CEW. TELS produced the maps. A, FQB, ID, CDH, I, TEK, RK, RC-L, AM, ZM, R, P, LQ, MAQ, AS, IS, ES, S, LAT and COW provided data, and FA, FQB, NSL, MM, LQ, SO, and LAT obtained additional data. All authors (except CDH, I, TEK, RK, ZM, R, P, AS, IS, ES, S and LAT) discussed the manuscript contents at the workshop. All authors reviewed and agreed on the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brearley, F.Q., Adinugroho, W.C., Cámara-Leret, R. et al. Opportunities and challenges for an Indonesian forest monitoring network. Annals of Forest Science 76, 54 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0840-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0840-0