Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a genetic multisystem disorder with prominent skin involvement including facial angiofibromas that often appear in early childhood. Here we report the case of a 12-year-old girl with widespread disfiguring facial angiofibromas that were successfully treated with topical rapamycin, a mTOR inhibitor. A sustained remission of skin lesions was documented in detail over a 3-year follow-up. This case highlights the fact that topical rapamycin is a useful option in treating TSC-associated skin lesions. Especially in medically complex patients topical treatment may lessen the need for surgical interventions, reducing the risks of surgery, its adverse effects and permanent scarring. However, there is no standard dose or formulation at present. Topical rapamycin appears safe, but long-term maintenance therapy is necessary to prevent facial lesions from regrowth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disease characterized by excess cell growth and proliferation, resulting in benign tumors and other abnormal tissue in multiple organs, including the skin [1, 2]. TSC is caused by inactivity of either of the two tumor suppressor genes, TSC1 or TSC2, encoding hamartin and tuberin [3, 4]. These proteins play an important role in the control of cell proliferation and differentiation through negative regulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). mTORC1 inhibitors such as rapamycin (sirolimus) or everolimus suppress tumor growth by reestablishing inhibition of mTORC1 and have been used as a targeted therapy for non-dermatologic manifestations in TSC (e.g., subependymal giant cell astrocytomas or kidney angiomyolipomas) [5].

Facial angiofibroma, previously known as ‘adenoma sebaceum’, is the most common TSC lesion to occur on the face [6] and represents a visible and often disfiguring stigma of the disease [7]. Invasive treatment options including cryosurgery, curettage, dermabrasion, chemical peeling, excision, and laser therapy are often used to treat disfiguring or bleeding lesions [8]. Benefits of these invasive procedures have to be balanced against the risks of permanent scarring, sedation in medically complex patients and incomplete removal of lesions as well as costs. Off-label use of topical rapamycin has been suggested as a non-invasive alterative approach to treating facial angiofibromas in pediatric TSC patients [9, 10].

Case Report

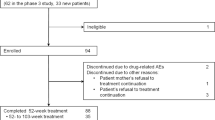

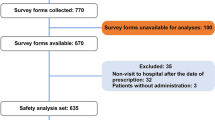

We present a 12-year-old girl with a definitive diagnosis of TSC (TSC2 mutation) [11] and wide-spread disfiguring facial angiofibromas (Fig. 1a, b). Other TSC-related manifestations include subependymal nodules, focal epilepsy, intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, a cardiac rhabdomyoma, renal angiomyolipoma, retinal astrocytoma, scoliosis and primary enuresis. After obtaining consent, the patient received a twice-daily treatment every-day schedule with a 0.1% rapamycin ointment. The 100 g ointment was compounded by a local pharmacy, using 100 crushed 1-mg sirolimus oral tablets, paraffin and petrolatum.

This treatment regimen, started in August 2013, led to a marked reduction of angiofibromas during the first 16 weeks (Fig. 1c). No adverse effects were observed during the treatment period, and negative plasma rapamycin levels were reassuring against significant systemic drug levels. After a course of almost 1 year, when almost all angiofibromas had vanished (Fig. 2), the topical treatment was discontinued for 3 months and recurrence was evaluated. Previously faded angiofibromas were found to reoccur (Fig. 3a). Therefore, topical rapamycin therapy was restarted, again with a marked treatment response (Fig. 3b). We evaluated the increased size of previously faded angiofibromas after discontinuing treatment because of the patient’s adolescence and not for any ‘rebound effect.’ At the time of this report, the patient is still using the off-label medication with good response. Informed consent was obtained from the patient and her parents for being included in the study.

Conclusion

Emerging evidence suggests that topical mTORC1 inhibitors, such as rapamycin, appear to be safe and effective treatment options for TSC-related cutaneous manifestations, although long-term outcome data are pending [8]. To the best of our knowledge, this report of a 3-year follow-up is the longest published to date. Table 1 summarizes previously used topical rapamycin therapy for angiofibromas with at least 6-month treatment regimes. Topical rapamycin appears safe, but long-term maintenance therapy is necessary to prevent facial lesions from regrowth. There is only a single published randomized controlled trial evaluating topical rapamycin therapy versus placebo [12]. Although the subjects in the treatment arms reported greater subjective improvement compared to subjects in the placebo arm, the study was not powered to reach statistical difference. Therefore, further randomized controlled clinical trials and direct comparison to invasive surgical treatment modalities are clearly desirable to establish the optimal treatment protocols and dosage for topical mTORC1 inhibitors.

References

DiMario FJ Jr, Sahin M, Ebrahimi-Fakhari D. Tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62:633–48.

Mann L, Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Heinrich B, Flotats-Bastardas M, Gortner L, von Gontard A, Niemcyzk J, Poryo M, Meyer S. [ESPED-Survey: TSC-disease in children and adolescents: preliminary results from a German epidemiological survey]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2016. doi:10.1007/s10354-016-0522-6.

Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:657–68.

Jozwiak J, Jozwiak S, Wlodarski P. Possible mechanisms of disease development in tuberous sclerosis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:73–9.

Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, Bebin EM, Frost MD, Kuperman R, Witt O, Kohrman MH, Flamini JR, Wu JY, Curatolo P, de Vries PJ, Berkowitz N, Niolat J, Jozwiak S. Long-term use of everolimus in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: final results from the EXIST-1 study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0158476.

Schwartz RA, Fernandez G, Kotulska K, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis complex: advances in diagnosis, genetics, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:189–202.

Muzykewicz DA, Newberry P, Danforth N, Halpern EF, Thiele EA. Psychiatric comorbid conditions in a clinic population of 241 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;11:506–13.

Jozwiak S, Sadowski K, Kotulska K, Schwartz RA. Topical use of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors in tuberous sclerosis complex—a comprehensive review of the literature. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;61:21–7.

Haemel AK, O’Brian AL, Teng JM. Topical rapamycin: a novel approach to facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:715–8.

Tu J, Foster RS, Bint LJ, Halbert AR. Topical rapamycin for angiofibromas in paediatric patients with tuberous sclerosis: follow up of a pilot study and promising future directions. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:63–9.

Northrup H, Krueger DA, International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus G. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243–54.

Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, Samuels J, Slopis J, Woerner A, Northrup H. Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topically applied rapamycin. Drugs R D. 2012;12:121–6.

Pynn EV, Collins J, Hunasehally PR, Hughes J. Successful topical rapamycin treatment for facial angiofibromata in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:e120–3.

Park J, Yun SK, Cho YS, Song KH, Kim HU. Treatment of angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex: the effect of topical rapamycin and concomitant laser therapy. Dermatology. 2014;228:37–41.

Knopfel N, Martin-Santiago A, Bauza A, Hervas JA. Topical 0.2% rapamycin to treat facial angiofibromas and hypomelanotic macules in tuberous sclerosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:802–3.

Salido R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Cuevas-Asencio I, Ruano J, Galan-Gutierrez M, Velez A, Moreno-Gimenez JC. Sustained clinical effectiveness and favorable safety profile of topical sirolimus for tuberous sclerosis—associated facial angiofibroma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:1315–8.

Foster RS, Bint LJ, Halbert AR. Topical 0.1% rapamycin for angiofibromas in paediatric patients with tuberous sclerosis: a pilot study of four patients. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:52–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Darius Ebrahimi-Fakhari (Boston, MA, USA) for discussions. The authors are very grateful to the patient and her family for their kind support of this study.

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Daniel Ebrahimi-Fakhari, Cornelia Sigrid Lissi Müller, Sascha Meyer, Marina Flotats-Bastardas, Thomas Vogt and Claudia Pföhler have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and her parents for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The data sets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/B887F0602946756B.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ebrahimi-Fakhari, D., Müller, C.S.L., Meyer, S. et al. Topical Rapamycin for Facial Angiofibromas in a Child with Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC): A Case Report and Long-Term Follow-up. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 7, 175–179 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-017-0174-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-017-0174-5