Abstract

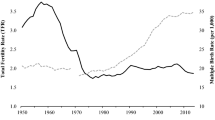

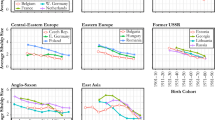

One of the most consistent patterns in the social sciences is the relationship between sibship size and educational outcomes: those with fewer siblings outperform those with many. The resource dilution (RD) model emphasizes the increasing division of parental resources within the nuclear family as the number of children grows, yet it fails to account for instances when the relationship between sibship size and education is often weak or even positive. To reconcile, we introduce a conditional resource dilution (CRD) model to acknowledge that nonparental investments might aid in children’s development and condition the effect of siblings. We revisit the General Social Surveys (1972–2010) and find support for a CRD approach: the relationship between sibship size and educational attainment has declined during the first half of the twentieth century, and this relationship varies across religious groups. Findings suggest that state and community resources can offset the impact of resource dilution—a more sociological interpretation of sibship size patterns than that of the traditional RD model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note the overlap between SRD and the quantity-quality model of fertility (Becker and Tomes 1976). The proponents write, “An increase in the quantity of children raises the cost or shadow price of the quality of children” (p. 143).

A less common phasing of the RD model is “resource depletion theory” (e.g., Fingerman et al. 2009).

Sibship size associations are generally stronger for educational outcomes, such as years of education attained and high school and college graduation, but are weaker for cognitive skills (Steelman et al. 2002).

Of course, pro-fertility communities likely support parents of both large and small families, but this help may matter more for children in large families, for whom parental resources are stretched thin.

Interestingly, as the relationship between education level and expected number of children is negative for the average American, the expected number of children increases modestly as education levels increase among Mormons (Heaton et al. 2004). Specifically, using the General Social Survey, Heaton et al. (2004) found a slight increase from 3.5 expected children among Mormon high school graduates (2.5 U.S. average) to about 4.0 among individuals with a graduate degree (2.0 U.S. average). Tests for statistical significance were not performed.

Curtis et al. (2015) found that tithing contributions are more likely among lifelong Mormons than among converts.

Unlike other denominations, the LDS congregation size is capped at approximately 600 members with membership in a given ward determined by preset “ward boundaries” (Chaves 2006). This results in two potentially advantageous outcomes for families in need. First, there are no large Mormon “megachurches,” which would likely limit interaction with leadership. Second, because ward boundaries are typically drawn to include a socioeconomically diverse membership, wards are more socioeconomically diverse than they might otherwise be if members were to choose their own congregations.

As with most studies of Mormons, these statistics are generated from a small number of cases (n ≈ 50).

Analyses performed with and without these restrictions reveal little change in the estimates. For the sibling measure, the cut point at 24 siblings is admittedly arbitrary but does represent a slight drop in the number of cases moving from 23 (n = 14) to 24 siblings (n = 4) reported. We also analyzed the sibling variable as categorical (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 compared with 5 or more), finding similar declining associations of educational attainment across decades of birth.

This measure does not allow us to distinguish siblings living in the household from those who are not, or to determine precisely how long a particular sibling lived in the home. For example, an individual may have a stepsibling who did not become part of the family until after the respondent completed his or her education.

We also considered separating Utah Mormons from other Mormons, but there were too few cases in Utah and surrounding states to conduct reliable analyses.

Because the wording for this question changed after 1993, we include a binary variable (Mother Employment Flag) indicating whether the survey was pre- or post-1993.

When comparing analyses with categorical versus continuous treatment of the family background measures, we found that these transformations did not meaningfully impact our results.

When these measures were analyzed as categorical variables (i.e. suburb, city, and so on; East South Central, Middle Atlantic, and so on), our substantive results were relatively unchanged.

Birth years of 1900–1904 and 1978–1979 had too few cases for independent regression analyses. Also, given that the data begin in 1905, Fig. 1 starts in 1915, an artifact of the 10-year smoothed averages.

Of course, one potential challenge for this analysis is the fact that the dependent variable is a moving target: years of education attained increased in significant ways over the century. The relationship between sibship size and years of education attained might be sensitive to this overall change. In supplemental analyses, we addressed this possibility by predicting the deviation from the average years of education attained for those born in the same year, thereby normalizing the dependent variable by each year. We also did this for sibling size. Normalizing the dependent variable in this way or the independent variable of siblings did not change the overall patterns (see Tables 5, 6, and 7 in the appendix). Also, in supplemental models, we found little evidence that these patterns vary by urban/rural status.

Including the most recent wave of GSS data (2014) reveals that the reversing trend line for cohorts in the 1970s only increases for cohorts in the 1980s. In other words, the more recent association between sibship size and educational attainment appears to be returning to pre-1960s cohort levels. Analysis available upon request.

The coefficient for sibship size from Model 3 in Table 3 is –0.25 (–0.25 × 6 = –1.5).

Results indicate that the relationship between family background and educational attainment became weaker during the twentieth century. Family income (0.62), father’s occupational prestige (0.34), and parental education (1.11) all have positive coefficients for the main effect. All three measures have a negative coefficient for the interaction with cohort, indicating that the relationship with educational attainment became weaker (i.e., less positive).

The analyses require access to the GSS sensitive data, which contain information on the state in which the respondent was raised at age 16. We link the GSS sensitive data with data from the U.S. Census of Governments, which captures all spending on higher education from state and local sources every five years. State spending is measured the decade after the respondent’s birth. Because of sample size limitations, we also have to restrict analyses to those born in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.

In supplemental analyses we also explored whether the Mormon pattern also changed over time. We found little evidence that the religion-based patterns also interacted with the historical changes, but sample sizes became small, limiting our confidence in this analysis.

We also attempted to explain the Mormon interaction with indicators in the GSS of “community support.” We relied on past research that gauged “social capital” (Paxton 1999) using the GSS data with indicators such as trust in individuals and voluntary associations. In supplemental analyses, these indicators did not reduce the interaction to nonsignificance. We are uncertain about the value of these analyses, however, because our measures of social capital were taken among adults, and we are most interested in community-level investments respondents received while growing up.

We find evidence of this pattern with the inclusion of the 2014 GSS data. Results available upon request.

In supplemental analyses, we attempted to move in this direction but confronted data obstacles. For example, to understand mechanisms for the Mormon interaction coefficient, we performed supplementary analyses of the relationship between sibship size and educational outcome with the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) (Harris et al. 2003). We found that the estimate for the Mormon–sibling size interaction was in the right direction but not statistically significant. This may be partly due to the Add Health data, which had a relatively small sample of Mormons (n = 210).

References

Aaronson, D., & Mazumder, B. (2008). Intergenerational economic mobility in the United States, 1940 to 2000. Journal of Human Resources, 43, 139–172.

Albrecht, S. L. (1998). The consequential dimension of Mormon religiosity. In J. T. Duke (Ed.), Latter-day Saint social life: Social research on the LDS church and its members (pp. 253–292). Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Albrecht, S. L., & Heaton, T. B. (1998). Secularization, higher education, and religiosity. In J. T. Duke (Ed.), Latter-day Saint social life: Social research on the LDS church and its members (pp. 293–314). Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Alwin, D. F. (1991). Family of origin and cohort differences in verbal ability. American Sociological Review, 56, 625–638.

Angrist, J., Lavy, V., & Schlosser, A. (2010). Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Labor Economics, 28, 773–824.

Anh, T. S., Knodel, J., Lam, D., & Friedman, J. (1998). Family size and children’s education in Vietnam. Demography, 35, 57–70.

Atkinson, A. B., Piketty, T., & Emmanuel, S. (2011). Top incomes in the long run of history. Journal of Economic Literature, 49, 3–71.

Becker, G. S., & Tomes, N. (1976). Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 84, 143–162.

Biblarz, T. J., Bengtson, V. L., & Bucur, A. (1996). Social mobility across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58, 188–200.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2007). Older and wiser? Birth order and IQ of young men (NBER Working Paper No. 13237). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2010). Small family, smart family? Family size and the IQ scores of young men. Journal of Human Resources, 45, 33–58.

Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography, 18, 421–442.

Blake, J. (1986). Number of siblings, family background, and the process of educational attainment. Social Biology, 33, 5–21.

Blake, J. (1989). Family size and achievement (Vol. 3). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American occupational structure. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Bobbitt-Zeher, D., Downey, D. B., & Merry, J. (2013, August). Are there long-term consequences to growing up without siblings? Likelihood of divorce among only children. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, New York, NY.

Boudon, R. (1976). Comment on Hauser’s review of education, opportunity, and social inequality. American Journal of Sociology, 81, 1175–1187.

Bound, J., & Turner, S. (2002). Going to war and going to college: Did World War II and the GI Bill increase educational attainment for returning veterans? Journal of Labor Economics, 20, 784–815.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buchmann, C. (2000). Family structure, parental perceptions, and child labor in Kenya: What factors determine who is enrolled in school? Social Forces, 78, 1349–1378.

Cáceres-Delpiano, J. (2006). The impacts of family size on investment in child quality. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 738–754.

Chaves, M. (2006). All creates great and small: Megachurches in context. Review of Religious Research, 47, 329–346.

Chernichovsky, D. (1985). Socioeconomic and demographic aspects of school enrollment and attendance in rural Botswana. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 33, 319–332.

Chu, C. Y. C., Xie, Y., & Yu, R.-R. (2007). Effects of sibship structure revisited: Evidence from intrafamily resource transfer in Taiwan. Sociology of Education, 80, 91–113.

Conley, D., & Glauber, R. (2006). Parental educational investment and children’s academic risk estimates of the impact of sibship size and birth order from exogenous variation in fertility. Journal of Human Resources, 41, 722–737.

Cooper, M. (2014). Cut adrift: Families in insecure times. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Curtis, D. W., Evans, V., & Cnaan, R. A. (2015). Charitable practices of Latter-day Saints. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44, 146–162.

Dahl, G. B., & Ransom, M. R. (1999). Does where you stand depend on where you sit? Tithing donations and self-serving beliefs. American Economic Review, 89, 703–727.

Davies, D. J. (2003). An introduction to Mormonism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, J. A., Smith, T. W., & Marsden, P. V. (2009). General Social Surveys, 1972–2006 [Cumulative file]. Storrs, CT; and Ann Arbor, MI: Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, University of Connecticut; and Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributors]. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04697.v4

Dean, K. C. (2010). Almost Christian: What the faith of our teenagers is telling the American Church. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Desai, S. (1995). When are children from large families disadvantaged? Evidence from cross-national analyses. Population Studies, 49, 195–210.

Downey, D. B. (1995). When bigger is not better: Family size, parental resources, and children’s educational performance. American Sociological Review, 60, 746–761.

Downey, D. B. (2001). Number of siblings and intellectual development. The resource dilution explanation. American Psychologist, 56, 497–504.

Downey, D. B., & Condron, D. J. (2004). Playing well with others in kindergarten: The benefit of siblings at home. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 333–350.

Dumont, A. (1890). Dépopulation et civilisation; Étude démographique [Depopulation and civilization: A demographic study]. Paris, France: Lecrosnier et Babé.

Dunn, E. (1996). Money, morality and modes of civil society among American Mormons. In C. Hann & E. Dunn (Eds.), Civil society: Challenging western models (pp. 27–49). London, UK: Routledge.

Dynarski, S. M. (2003). Does aid matter? Measuring the effect of student aid on college attendance and completion. American Economic Review, 93, 279–288.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Erickson, L. D., McDonald, S., & Elder, G. H. (2009). Informal mentors and education: Complementary or compensatory resources? Sociology of Education, 82, 344–367.

Erickson, L. D., & Phillips, J. W. (2012). The effect of religious-based mentoring on educational attainment: More than just a spiritual high? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51, 568–587.

Featherman, D. L., & Hauser, R. M. (1978). Opportunity and change. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Fingerman, K., Miller, L., Birditt, K., & Zarit, S. (2009). Giving to the good and the needy: Parental support of grown children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 1220–1233.

Fischer, C., & Hout, M. (2006). Century of difference: How America changed in the last one hundred years. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gailbraith, R. C. (1982). Sibling spacing and intellectual development: A closer look at the confluence model. Developmental Psychology, 18, 151–174.

Gomes, M. (1984). Family size and educational attainment in Kenya. Population and Development Review, 10, 647–660.

Grusky, D. B., & DiPrete, T. A. (1990). Recent trends in the process of stratification. Demography, 27, 617–637.

Guo, G., & VanWey, L. (1999a). Sibship size and intellectual development: Is the relationship causal? American Sociological Review, 64, 169–187.

Guo, G., & VanWey, L. (1999b). The effects of closely spaced and widely spaced sibship size on intellectual development. American Sociological Review, 64, 199–206.

Harris, K. M., Florey, F., Tabor, J., Bearman, P. S., Jones, J., & Udry, J. R. (2003). The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health [Study design]. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design

Hauser, R. M., & Featherman, D. L. (1977). The process of stratification. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Heaton, T. B., Bahr, S. J., & Jacobson, C. K. (2004). A statistical profile of Mormons: Health, wealth and social life. Lewiston, NY: Edsim Mellen.

Hoffmann, J. P., Lott, B. R., & Jeppsen, C. (2010). Religious giving and the boundedness of rationality. Sociology of Religion, 71, 323–348.

Hout, M. (1988). More universalism, less structural mobility: The American occupational structure in the 1980s. American Journal of Sociology, 93, 1358–1400.

Kidwell, J. S. (1981). Number of siblings, sibling spacing, sex, and birth order: Their effects on perceived parent-child relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 43, 315–332.

Kuo, H. H. D., & Hauser, R. M. (1997). How does size of sibship matter? Family configuration and family effects on educational attainment. Social Science Research, 26, 69–94.

Li, H., Zhang, J., & Zhu, Y. (2008). The quantity-quality trade-off of children in a developing country: Identification using Chinese twins. Demography, 45, 223–243.

Lu, Y., & Treiman, D. J. (2008). The effect of sibship size on educational attainment in China: Period variations. American Sociological Review, 73, 813–834.

Ludlow, D. H. (Ed.). (1992). Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Mangum, G. L., & Blumell, B. D. (1993). The Mormons’ war on poverty: A history of LDS welfare 1830–1990 (Vol. 8). Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

Maralani, V. (2008). The changing relationship between family size and educational attainment over the course of socioeconomic development: Evidence from Indonesia. Demography, 45, 693–717.

Marteleto, L. (2010). Family size and schooling throughout the demographic transition: Evidence from Brazil. Demographic Research, 23(article 15), 421–444. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.15

Marteleto, L. J., & de Souza, L. R. (2012). The changing impact of family size on adolescents’ schooling: Assessing the exogenous variation in fertility using twins in Brazil. Demography, 49, 1453–1477.

Mayer, S. E., & Lopoo, L. M. (2005). Has the intergenerational transmission of economic status changed? Journal of Human Resources, 40, 169–185.

Mayer, S. E., & Lopoo, L. M. (2008). Government spending and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Public Economics, 92, 139–158.

McBride, M. (2007). Club Mormon: Free-riders, monitoring, and exclusion in the LDS Church. Rationality and Society, 19, 395–424.

McHale, S. M., Updegraff, K. A., & Whiteman, S. D. (2012). Sibling relationships and influences in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 913–930.

Mercy, J. A., & Steelman, L. C. (1982). Familial influence on the intellectual attainment of children. American Sociological Review, 47, 532–542.

Murray, C. (1984). Losing ground: American social policy, 1950–1980. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Parcel, T. L., & Menaghan, E. G. (1994). Parents’ jobs and children’s lives. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyeter.

Parish, W. L., & Willis, R. J. (1993). Daughters, education, and family budgets Taiwan experiences. Journal of Human Resources, 28, 863–898.

Park, H. (2008). Public policy and the effect of sibship size on educational achievement: A comparative study of 20 countries. Social Science Research, 37, 874–887.

Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 88–127.

Pew Research Center. (2008). U.S. Religious Landscape Survey. Religious affiliation: Diverse and dynamic (Report). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. Retrieved from http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf

Pew Research Center. (2012). Mormons in America: Certain in their beliefs, uncertain of their place in society (Report). Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. Retrieved from http://www.pewforum.org/files/2012/01/Mormons-in-America.pdf

Powell, B., & Steelman, L. C. (1993). The educational benefits of being spaced out: Sibship density and educational progress. American Sociological Review, 58, 367–381.

Powell, B., Werum, R., & Steelman, L. C. (2004). Macro causes, micro effects: Linking public policy, family structure, and educational outcomes. In D. Conley & K. Albright (Eds.), After the bell—Family background, public policy, and educational success (pp. 111–144). New York, NY: Routledge.

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Murnane (Eds.), Whither opportunity? Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 91–116). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Rodgers, J. L., Cleveland, H. H., van den Oord, E., & Rowe, D. C. (2000). Resolving the debate over birth order, family size, and intelligence. American Psychologist, 55, 599–612.

Rosenzweig, M. R., & Wolpin, K. I. (1980). Life-cycle labor supply and fertility: Causal inferences from household models. Journal of Political Economy, 88, 328–348.

Shavit, Y., & Pierce, J. L. (1991). Sibship size and educational attainment in nuclear and extended families: Arabs and Jews in Israel. American Sociological Review, 56, 321–330.

Smith, C., & Denton, M. L. (2005). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

StataCorp. (2013). Stata statistical software: Release 13 [Software]. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Steelman, L. C., & Powell, B. (1989). Acquiring capital for college: The constraints of family configuration. American Sociological Review, 54, 844–855.

Steelman, L. C., Powell, B., Werum, R., & Carter, S. (2002). Reconsidering the effects of sibling configuration: Recent advances and challenges. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 243–269.

Sudha, S. (1997). Family size, sex composition and children’s education: Ethnic differentials over development in Peninsular Malaysia. Population Studies, 51, 139–151.

Taber, S. B. (1993). Mormon lives: A year in the Elkton Ward. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Tanzi, V., & Schuknecht, L. (2000). Public spending in the 20th century: A global perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Xu, J. (2008). Sibship size and educational achievement: The role of welfare regimes cross-nationally. Comparative Education Review, 52, 412–436.

Ye, H., & Wu, X. (2011, April). Fertility decline and educational gender inequality in China. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America, Washington, DC. Retrieved from http://paa2011.princeton.edu/papers/112516

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gibbs, B.G., Workman, J. & Downey, D.B. The (Conditional) Resource Dilution Model: State- and Community-Level Modifications. Demography 53, 723–748 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0471-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0471-0