Abstract

Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) are widely used for treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus; however, there have been concerns that GLP-1RA treatment may be associated with an increased incidence of pancreatitis. This study aimed to evaluate the incidence of pancreatitis in a pooled population of type 2 diabetes trials from the clinical development program of the GLP-1RA exenatide as well as to describe patient-level data for all reported cases.

Methods

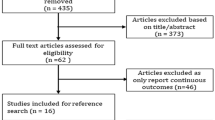

The primary analysis examined pooled data among patients with type 2 diabetes from the controlled arms of 35 trials (ranging from 4 to 234 weeks’ duration) in the integrated clinical databases for exenatide twice daily, once weekly, and once-weekly suspension, excluding comparator arms with other incretin-based therapies. The exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) of pancreatitis was calculated for exenatide and non-exenatide (non-incretin-based therapy or placebo) treatment groups. Patient-level data were described for all pancreatitis incidences.

Results

The primary analysis included 5596 patients who received exenatide and 4462 in the non-exenatide group. The mean duration of study medication exposure for the exenatide and non-exenatide treatment groups was 57.0 and 47.9 weeks, respectively. Pancreatitis was diagnosed in 14 patients (exenatide, n = 8; non-exenatide, n = 6), of whom 13 recovered with or without sequelae. The pancreatitis EAIR was 0.1195 events per 100 patient-years [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.0516–0.2154] in the exenatide group versus 0.1276 events per 100 patient-years (95% CI 0.0468–0.2482) in the non-exenatide treatment group. The EAIR ratio for the exenatide versus non-exenatide treatment group was 0.761 (95% CI 0.231–2.510).

Conclusion

In this pooled analysis of 10,058 patients among studies comparing exenatide with other glucose-lowering medications or placebo, pancreatitis was rare. The EAIRs of pancreatitis were low and similar between exenatide and non-exenatide treatment groups. No evidence of an association between exenatide and pancreatitis was observed.

Funding

Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain Language Summary

Exenatide is a noninsulin injectable treatment for type 2 diabetes. There have been concerns about whether exenatide and other drugs that work in a similar way might be associated with increased risk of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas). To assess new cases of pancreatitis occurring during treatment, we combined data from 35 clinical studies of exenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes. These studies included 5596 patients who received exenatide and 4462 patients who received placebo or a diabetes therapy that was unrelated to exenatide, in addition to their ongoing, usual treatment, for an average of about 1 year. The total treatment time (exposure) for exenatide across all 35 clinical trials was 6696 years. Fourteen patients developed pancreatitis (eight who had received exenatide and six who had received a different treatment). We provide details about each case of pancreatitis. After adjusting for different exposure times for each treatment, the number of new cases of pancreatitis expected to occur over 1 year was similar in patients treated with exenatide and those who received other unrelated treatments. We estimated that, for every 1000 patients who received exenatide or another treatment, we would expect to see 1.2 or 1.3 corresponding cases of pancreatitis per year, respectively. Our results were consistent with those from previous studies of pancreatitis in patients treated with exenatide or related therapies. In summary, our study found that pancreatitis occurred very rarely in patients treated with exenatide and at a similar rate as that in patients who received other treatments.

Introduction

Incretin-based therapies, including glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs) and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, are widely used for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Exenatide, the first approved GLP-1RA, effectively improves glycemic control through enhanced glucose-dependent insulin secretion, inhibition of glucagon release, delayed gastric emptying, and weight loss induced by reduced food intake [1,2,3,4]. Since 2007, a number of postmarketing cases of acute pancreatitis have been reported with GLP-1RA treatment (including exenatide, liraglutide, and others) as well as with DPP-4 inhibitors, prompting the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue safety warnings about a possible temporal relationship between pancreatitis and agents in these classes [5,6,7,8,9]. Subsequent to these reports, all currently marketed GLP1-RA and DPP-4 inhibitors have label warnings regarding pancreatitis.

In 2013, the FDA and the European Medicines Agency independently conducted comprehensive evaluations of preclinical and clinical data submitted in support of marketing applications of incretin-based drugs and collected additional postmarketing safety data [10, 11]. Both the FDA and the European Medicines Agency concluded that the current data do not suggest an increased risk of pancreatitis events with incretin-based therapies but warned that pancreatitis would continue to be considered a risk associated with these therapies until additional definitive clinical and real-world data become available [10, 11].

Since that time, multiple studies have been conducted to investigate the potential relationship between incretin-based therapies—GLP-1RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors—and pancreatitis. Importantly, several long-term randomized controlled clinical trials to evaluate cardiovascular outcomes with GLP-1RAs and DPP-4 inhibitors were recently completed [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Most of these trials, including results of EXSCEL (Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01144338) [12], adjudicated pancreatic events to enhance understanding of the risk of pancreatitis associated with incretin-based therapies.

The present study, which complements adjudicated data on pancreatic events from the EXSCEL trial, aimed to investigate the incidence of pancreatitis and review the clinical data associated with identified pancreatitis events using pooled data from 35 randomized trials across multiple exenatide formulations in the exenatide clinical development program. To account for differences in the duration of drug exposure, the exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) for pancreatitis, which provides a measure of the number of patients who had pancreatitis divided by the person-time at risk, was calculated for exenatide-treated and non-exenatide-treated patients. To better understand the nature of observed cases, patient-level data were compiled and reviewed for all cases of pancreatitis.

Methods

Study Design

The primary analysis included integrated, pooled clinical data from 35 clinical trials for the exenatide twice daily (BID), once weekly (QW), and QW suspension programs that were completed before 2016. The analysis included randomized, placebo-, or active comparator-controlled phase 2/3 studies of exenatide used as monotherapy or add-on therapy to metformin, a sulfonylurea, a thiazolidinedione, or insulin for 4–234 weeks in patients with T2DM. Both double-blind and open-label studies were included; however, uncontrolled extension periods of studies were excluded. Studies with short exenatide exposure (defined as < 4 weeks) and studies conducted in healthy participants (e.g., patients without T2DM) were also excluded. In addition, GLP-1RAs other than exenatide and other incretin-based comparator therapies were excluded from the analysis. Two groups were analyzed: a group treated with exenatide and a non-exenatide group, which was treated with a non-incretin-based active comparator therapy or placebo. Detailed methodology and primary findings for each study included in this analysis have been previously published (Electronic Supplementary Material Table S1). In all studies, patients were followed up until study completion or early discontinuation from study treatment. Notably, for most studies, pancreatitis events were not adjudicated by an external review committee.

Statistical Analysis

Adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs were reported by study investigators, consistent with guidance from the International Conference on Harmonisation. AEs were coded based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) versions 16.0 and 17.0. Cases of pancreatitis in the exenatide program were identified through the following MedDRA preferred terms: “Pancreatitis,” “Pancreatitis, acute,” “Pancreatitis, chronic,” “Pancreatitis haemorrhagic,” “Pancreatic haemorrhage,” “Pancreatitis necrotising,” “Pancreatitis necrotizing,” “Pancreatic necrosis,” “Pancreatitis relapsing,” “Pancreatic pseudocyst,” “Pancreatic pseudocyst drainage,” “Pancreatitic phlegmon,” “Hereditary pancreatitis,” “Ischaemic pancreatitis,” “Oedematous pancreatitis,” “Pancreatic abscess,” “Pancreatorenal syndrome,” and “Cullen’s sign.”

Descriptive statistics were provided for demographics and baseline variables. The duration of exposure was calculated using the time from first dose to last dose. The EAIR was calculated for pancreatitis events in the exenatide and non-exenatide groups. For EAIR calculations, exposure time was defined as the time to the first event, if an event occurred, or duration of drug exposure. The confidence interval (CI) of the EAIR was calculated from inverse gamma distribution assuming Poisson distribution for pancreatitis events. The ratio of EAIRs was computed from a Poisson regression weighted by the probabilities of receiving exenatide treatment in each individual study, known as the inverse probability of treatment weighted estimator. The Poisson regression was estimated using a generalized estimating equation with study as a cluster variable and compound symmetry covariance structure to account for within-study correlations. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

The power to detect a meaningful difference in incidence was limited by the low incidence of pancreatitis and short follow-up time in the study. For example, assuming that the background EAIR is 0.12 per 100 patient-years and patients treated with exenatide have twice the risk of pancreatitis than the comparator group (i.e., an EAIR ratio of 2, which is usually considered a large difference), to achieve 80% power for detecting this difference, a sample size of at least 39,208 patients with 0.5 years of follow-up or 5596 patients with > 3.5 years of follow-up in each treatment group would be needed for a one-sided type-1 error rate of 0.025. In our data, a sample size of 5596 patients (n for pooled exenatide patients) in each treatment group, with a median follow-up time of 0.5 years, will provide only 20% power for detecting an EAIR ratio of 2.0. The power calculation assumed a constant incidence rate over time and was conducted using Power Analysis and Sample Size 2008 software (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, UT, USA).

Patient-level data were compiled and reviewed by the authors, including patient characteristics, pertinent medical history, risk factors associated with pancreatitis, concomitant medication use, biochemical findings such as lipase and amylase levels (where available), radiologic reports (where available), pancreatitis event latency, and outcomes and management.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study involves only analysis of previously published data and contains no new data from human participants. Therefore, informed consent and approval by an Institutional Ethics Committee were not required. All subjects consented, and ethics approvals were obtained for the original data collection as part of the original clinical trials.

Results

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Demographics and clinical characteristics were well balanced between patients who were treated with exenatide (n = 5596) and those in the non-exenatide group (n = 4462) (Table 1). Both groups were similar in terms of age, sex, duration of T2DM, body weight, body mass index, and glycated hemoglobin. Baseline blood pressure, serum triglycerides, and serum cholesterol concentrations were similar between groups. Use of concomitant medications that have been associated with the development of acute pancreatitis, including statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium-channel blockers, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was also similar.

Duration of Exposure to Exenatide

Mean (minimum–maximum) exposure of study medication was 57.0 weeks (0.1–251.9 weeks) and 47.9 weeks (0.1–233.6 weeks) in the exenatide and non-exenatide treatment groups, respectively. Only 7.5% of exenatide-treated patients (n = 422) were exposed to exenatide for ≤ 30 days, while 30.6% (n = 1714) were exposed to exenatide for > 1 year. The total exposure to exenatide was 6696 years.

Incidence of Pancreatitis with Exenatide Versus Non-Exenatide Treatment

Pancreatitis was reported in 14 patients across the clinical development program [exenatide, n = 8 (0.14%); non-exenatide treatment, n = 6 (0.13%)] (Table 2). No patient reported > 1 pancreatitis event. Among exenatide-treated patients, five were treated with exenatide BID and three with exenatide QW. No cases of pancreatitis were reported in patients treated with exenatide QW suspension, although only 204 of the 5596 exenatide-treated patients received this formulation. In the non-exenatide group, patients with pancreatitis received placebo (n = 1), insulin (n = 2), a sulfonylurea (n = 1), or pioglitazone (n = 2).

The EAIR of pancreatitis was similar between the exenatide and non-exenatide groups [0.1195 events per 100 patient-years (95% CI 0.0516–0.2154) and 0.1276 events per 100 patient-years (95% CI 0.0468–0.2482), respectively], with an EAIR ratio of 0.761 (95% CI 0.231–2.510; P = 0.6535) (Table 2).

Review of Pancreatitis Cases

Pancreatitis events ranged from mild to severe, and most events resolved with or without sequelae (Table 3). Four of the exenatide-treated patients and five of the non-exenatide-treated patients were hospitalized, and three and two patients, respectively, withdrew from the study. No deaths occurred. Ten of the 14 events were reported as serious AEs (n = 5 in each group). Four cases of pancreatitis were assessed by the investigator as study-drug related or possibly study-drug related (exenatide BID, n = 2; exenatide QW, n = 2). The mean time to pancreatitis was comparable between groups.

Details of each pancreatitis case are provided in Table 4. Of the 14 patients with a pancreatitis event, 13 had events that resolved with or without sequelae, and one had an ongoing event during the study period that was of mild intensity and considered unrelated to the study drug. The time of event onset (latency) ranged from 9 to 772 days. For the 13 patients whose event resolved with or without sequelae, the duration of the pancreatitis events ranged from 3 to 101 days; nine patients had an event duration of < 14 days. Of the 14 patients with a pancreatitis event, 13 had > 1 risk factor for pancreatitis, including prior or concomitant treatment with a non-glucose-lowering therapy that is associated with increased risk of pancreatitis. Patients most commonly presented with abdominal pain, often accompanied by nausea. Eight patients had a history of cholecystitis, had prior cholecystectomy, or experienced cholelithiasis during the pancreatitis event. Diagnostic imaging results were available for ten patients (see Table 4 for details). Elevated amylase and lipase clinical laboratory measures were reported for ten and seven patients, respectively. No obvious differences in the case details were apparent between patients in the exenatide and non-exenatide groups.

Discussion

In this pooled analysis of 10,058 patients with T2DM from 35 clinical trials in the exenatide clinical development program, few cases of pancreatitis were reported. Treatment with exenatide was not found to be associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis compared with placebo or non-incretin–based active comparator in this population.

These data show that 8 of 5596 patients (0.14%) treated with exenatide had pancreatitis, of whom seven recovered with or without sequelae. For most cases, the study drug was not discontinued. Approximately half the patients who developed pancreatitis had a history of gallbladder disease, and most had received therapy from ≥ 1 of the drug classes known to be associated with pancreatitis. Importantly, T2DM itself is associated with a risk of pancreatitis [19, 20].

The results of the current study add to multiple studies that had previously explored the potential relationship between incretin-based therapies and pancreatitis, including preclinical experiments [21,22,23,24,25,26,27]; retrospective cohort, case–control, population-based, and other observational analyses [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]; meta-analyses of clinical study results [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]; and, as discussed below, large cardiovascular outcomes trials [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Previous studies have examined data pooled across 19 randomized clinical trials (n = 5594) of exenatide BID [52] or eight phase 3 studies (n = 4328) of exenatide QW [53]. These studies reported EAIRs for pancreatitis that were not statistically significantly different between exenatide BID and comparator (0.27 vs. 0.18 events per 100 patient-years; risk difference, 0.09) or were comparable between exenatide QW and comparator (0.5 vs. 0.5 events per 100 patient-years); however, these studies did not examine individual cases of pancreatitis.

Similar findings to those reported in the current article were observed with pooled analyses of pancreatitis in the clinical development program of two other GLP-1RAs, liraglutide and dulaglutide [54, 55]. A post hoc analysis of 18 phase 2 and phase 3 randomized clinical trials of a total of 9016 patients treated with liraglutide (5021 patient-years of exposure), placebo (397 patient-years of exposure), or active comparator (1354 patient-years of exposure) reported eight cases of acute pancreatitis with liraglutide and one case with an active comparator (glimepiride) [54]. The EAIRs of acute pancreatitis were 0.16 and 0.07 cases per 100 patient-years with liraglutide and total active comparators, respectively. Recognized risk factors for pancreatitis were observed in 75% of the acute pancreatitis cases with liraglutide treatment. In an assessment of 6005 patients in nine phase 2 and 3 clinical trials of dulaglutide (3531 patient-years of exposure), EAIRs were 0.085 patients per 100 patient-years for dulaglutide, 0.352 patients per 100 patient-years for placebo, and 0.471 patients per 100 patient-years for sitagliptin [55]. Adjudication confirmed three cases of acute pancreatitis with dulaglutide, three cases with sitagliptin, and one case with placebo; no adjudicated cases of pancreatitis occurred in the exenatide, metformin, or insulin glargine comparator groups. In our analysis, exenatide- and non-exenatide-treated patients had EAIRs of 0.12 and 0.13 events per 100 patient-years, respectively.

In four completed large, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that investigated long-term cardiovascular safety of a GLP-1RA in patients with T2DM, no significant difference in the incidence of pancreatitis was found between the GLP-1RA and placebo groups [12, 16,17,18]. Notably, each of these studies had an independent committee that adjudicated all potential cases of pancreatitis. In the EXSCEL trial, in which 14,752 patients were randomized to receive exenatide QW or placebo and were followed up for a median of 3.2 years, the percentage of patients who experienced acute pancreatitis was low [0.4% (n = 26) for exenatide QW and 0.3% (n = 22) for placebo] [12, 56]. The EAIRs of confirmed acute pancreatitis in the EXSCEL trial were similar for exenatide QW (0.12 events per 100 patient-years) and placebo (0.10 events per 100 patient-years). In the LEADER (Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01179048) trial of 9340 patients followed for 3.5–5 years, no statistically significant difference occurred in the percentage of patients who experienced acute pancreatitis between treatment groups [0.4% (n = 18) for liraglutide and 0.5% (n = 23) for placebo; P = 0.44] [18]. Furthermore, in LEADER the EAIRs for pancreatitis for patients treated with liraglutide or placebo were similar (0.11 or 0.17 events per 100 patient-years, respectively) [57]. The ELIXA (Evaluation of Lixisenatide in Acute Coronary Syndrome; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01147250) trial (n = 6068) demonstrated low and comparable percentages of confirmed pancreatitis events for patients treated with lixisenatide [0.2% (n = 5)] or placebo [0.3% (n = 8)], with mean durations of exposure of 690 and 712 days, respectively [16]. In SUSTAIN-6 (Trial to Evaluate Cardiovascular and Other Long-term Outcomes with Semaglutide in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01720446), 3297 patients were randomized to receive semaglutide QW 0.5 mg, semaglutide QW 1.0 mg, or volume-matched placebo for 2 years. The percentage of patients with acute pancreatitis was similar between groups treated with semaglutide [0.5% (n = 9)] or placebo [0.7% (n = 12)] [17]. The currently ongoing cardiovascular outcomes trial for dulaglutide, REWIND (Researching Cardiovascular Events with a Weekly Incretin in Diabetes; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01394952), will also adjudicate events of pancreatitis [58].

The results of the current study are consistent with recent meta-analyses of GLP-1RA clinical trials that do not observe an increased risk of pancreatitis with GLP-1RAs [59,60,61,62]. Conversely, three recent meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials of DPP-4 inhibitors reported an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. The first meta-analysis examined three prospective cardiovascular trials with 36,543 patients and reported an increased risk of acute pancreatitis with DPP-4 inhibitors [relative risk, 1.79 (95% CI 1.13–2.81)] [50]. The second meta-analysis examined 36 placebo-controlled studies with 54,664 patients and also found an increased risk of acute pancreatitis with DPP-4 inhibitors [relative risk, 1.57 (95% CI 1.03–2.39)] [51]. Finally, a meta-analysis of 38 randomized clinical trials including 59,404 patients reported an increased risk of acute pancreatitis with DPP-4 inhibitors compared with placebo or active comparators [Peto odds ratio, 1.72 (95% CI 1.18–2.53)] [63].

Several limitations were present in the current analysis. Patients had a relatively short exposure to exenatide, with most of the included studies having a duration of ≤ 6 months. Because many of these studies were conducted prior to the emergence of a potential pancreatic signal from postmarketing reports, limited confirmatory clinical data (e.g., amylase and lipase concentrations, imaging results) were available, detailed information on potential risk factors for pancreatitis (e.g., alcohol and tobacco use) was not collected, and pancreatic events were not formally adjudicated. As pancreatitis was a rare event, the integrated database that was used in the present study may not have been sufficiently large to investigate events of pancreatitis. Although the duration of the studies in the current analysis was limited, subsequently conducted long-term clinical trials and meta-analyses also have reported low incidences of pancreatitis [12, 16,17,18, 57, 59,60,61], and long-term data (up to 6 years) from the uncontrolled extension of DURATION-1 (n = 136) suggest a very low risk of pancreatitis, with only one case reported (EAIR of 0.1 event per 100 patient-years) [64].

Conclusion

In this pooled analysis from 35 trials (4–234 weeks’ duration) in the exenatide clinical development program, pancreatitis events were very rare. The incidence of pancreatitis was similar among exenatide-treated patients and those who were treated with placebo or a non-incretin-based active comparator, and demographics and baseline characteristics were similar between groups. Results from this study are consistent with findings from both large observational studies that mostly suggest there is no increased risk of pancreatitis associated with exenatide and from large cardiovascular outcome trials and meta-analyses that do not report an increased risk of pancreatitis with GLP-1RAs. Although cases of pancreatitis in the exenatide clinical development program were rare, physicians should remain vigilant in monitoring for symptoms indicative of pancreatitis [65, 66].

References

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018: (8) Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S73–85.

Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2628–35.

DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1092–100.

Linnebjerg H, Park S, Kothare PA, et al. Effect of exenatide on gastric emptying and relationship to postprandial glycemia in type 2 diabetes. Regul Pept. 2008;151:123–9.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Information for healthcare professionals: exenatide (marketed as Byetta)-10/2007. 2007. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722190645/https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124712.htm. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Information for healthcare professionals: exenatide (marketed as Byetta)-8/2008 update. 2008. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722190642/https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm124713.htm. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Information for healthcare professionals—acute pancreatitis and sitagliptin (marketed as Januvia and Janumet). 2009. https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20170722191334/https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/DrugSafetyInformationforHeathcareProfessionals/ucm183764.htm. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Questions and answers—safety requirements for victoza (liraglutide). 2010. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm198543.htm. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA investigating reports of possible increased risk of pancreatitis and pre-cancerous findings of the pancreas from incretin mimetic drugs for type 2 diabetes. 2013. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm343187.htm. Accessed 19 Apr 2018.

Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs–FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:794–7.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Assessment report for GLP-1 based therapies. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2013/08/WC500147026.pdf. Accessed 13 May 2017.

Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1228–39.

Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1317–26.

White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1327–35.

Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:232–42.

Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2247–57.

Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834–44.

Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311–22.

Noel RA, Braun DK, Patterson RE, Bloomgren GL. Increased risk of acute pancreatitis and biliary disease observed in patients with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:834–8.

Gonzalez-Perez A, Schlienger RG, Rodriguez LA. Acute pancreatitis in association with type 2 diabetes and antidiabetic drugs: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2580–5.

Nachnani JS, Bulchandani DG, Nookala A, et al. Biochemical and histological effects of exendin-4 (exenatide) on the rat pancreas. Diabetologia. 2010;53:153–9.

Gier B, Matveyenko AV, Kirakossian D, Dawson D, Dry SM, Butler PC. Chronic GLP-1 receptor activation by exendin-4 induces expansion of pancreatic duct glands in rats and accelerates formation of dysplastic lesions and chronic pancreatitis in the Kras(G12D) mouse model. Diabetes. 2012;61:1250–62.

Koehler JA, Baggio LL, Lamont BJ, Ali S, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation modulates pancreatitis-associated gene expression but does not modify the susceptibility to experimental pancreatitis in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:2148–61.

Engel SS, Williams-Herman DE, Golm GT, et al. Sitagliptin: review of preclinical and clinical data regarding incidence of pancreatitis. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:984–90.

Tatarkiewicz K, Belanger P, Gu G, Parkes D, Roy D. No evidence of drug-induced pancreatitis in rats treated with exenatide for 13 weeks. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:417–26.

Chadwick KD, Fletcher AM, Parrula MC, et al. Occurrence of spontaneous pancreatic lesions in normal and diabetic rats: a potential confounding factor in the nonclinical assessment of GLP-1-based therapies. Diabetes. 2014;63:1303–14.

Usborne A, Byrd RA, Meehan J, et al. An investigative study of pancreatic exocrine biomarkers, histology, and histomorphometry in male Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats given dulaglutide by subcutaneous injection twice weekly for 13 weeks. Toxicol Pathol. 2015;43:1093–102.

Wenten M, Gaebler JA, Hussein M, et al. Relative risk of acute pancreatitis in initiators of exenatide twice daily compared with other anti-diabetic medication: a follow-up study. Diabet Med. 2012;29:1412–8.

Dore DD, Seeger JD, Arnold Chan K. Use of a claims-based active drug safety surveillance system to assess the risk of acute pancreatitis with exenatide or sitagliptin compared to metformin or glyburide. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:1019–27.

Dore DD, Bloomgren GL, Wenten M, et al. A cohort study of acute pancreatitis in relation to exenatide use. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13:559–66.

Romley JA, Goldman DP, Solomon M, McFadden D, Peters AL. Exenatide therapy and the risk of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer in a privately insured population. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:904–11.

Dore DD, Hussein M, Hoffman C, Pelletier EM, Smith DB, Seeger JD. A pooled analysis of exenatide use and risk of acute pancreatitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:1577–86.

Funch D, Gydesen H, Tornoe K, Major-Pedersen A, Chan KA. A prospective, claims-based assessment of the risk of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer with liraglutide compared to other antidiabetic drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:273–5.

Lai YJ, Hu HY, Chen HH, Chou P. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and the risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes in Taiwan: a population-based cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1906.

Tseng CH. Sitagliptin increases acute pancreatitis risk within 2 years of its initiation: a retrospective cohort analysis of the National Health Insurance database in Taiwan. Ann Med. 2015;47:561–9.

Yabe D, Kuwata H, Kaneko M, et al. Use of the Japanese health insurance claims database to assess the risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with diabetes: comparison of DPP-4 inhibitors with other oral antidiabetic drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:430–4.

Chang CH, Lin JW, Chen ST, Lai MS, Chuang LM, Chang YC. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor use is not associated with acute pancreatitis in high-risk type 2 diabetic patients: a nationwide cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2603.

Singh S, Chang HY, Richards TM, Weiner JP, Clark JM, Segal JB. Glucagonlike peptide 1-based therapies and risk of hospitalization for acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based matched case-control study. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:534–9.

Faillie JL, Babai S, Crepin S, et al. Pancreatitis associated with the use of GLP-1 analogs and DPP-4 inhibitors: a case/non-case study from the French Pharmacovigilance Database. Acta Diabetol. 2014;51:491–7.

Thomsen RW, Pedersen L, Moller N, Kahlert J, Beck-Nielsen H, Sorensen HT. Incretin-based therapy and risk of acute pancreatitis: a nationwide population-based case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1089–98.

Liao KF, Lin CL, Lai SW, Chen WC. Sitagliptin use and risk of acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;27:76–9.

Garg R, Chen W, Pendergrass M. Acute pancreatitis in type 2 diabetes treated with exenatide or sitagliptin: a retrospective observational pharmacy claims analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2349–54.

Meier JJ, Nauck MA. Risk of pancreatitis in patients treated with incretin-based therapies. Diabetologia. 2014;57:1320–4.

Giorda CB, Sacerdote C, Nada E, Marafetti L, Baldi I, Gnavi R. Incretin-based therapies and acute pancreatitis risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Endocrine. 2015;48:461–71.

Wang T, Wang F, Gou Z, et al. Using real-world data to evaluate the association of incretin-based therapies with risk of acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis of 1,324,515 patients from observational studies. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:32–41.

Li L, Shen J, Bala MM, et al. Incretin treatment and risk of pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised and non-randomised studies. BMJ. 2014;348:g2366.

Alves C, Batel-Marques F, Macedo AF. A meta-analysis of serious adverse events reported with exenatide and liraglutide: acute pancreatitis and cancer. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98:271–84.

Monami M, Dicembrini I, Mannucci E. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and pancreatitis risk: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:48–56.

Monami M, Dicembrini I, Nardini C, Fiordelli I, Mannucci E. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and pancreatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:269–75.

Abbas AS, Dehbi HM, Ray KK. Cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular safety of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled cardiovascular outcome trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:295–9.

Rehman MB, Tudrej BV, Soustre J, et al. Efficacy and safety of DPP-4 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:48–58.

MacConell L, Brown C, Gurney K, Han J. Safety and tolerability of exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes: integrated analysis of 5594 patients from 19 placebo-controlled and comparator-controlled clinical trials. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2012;5:29–41.

MacConell L, Gurney K, Malloy J, Zhou M, Kolterman O. Safety and tolerability of exenatide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes: an integrated analysis of 4,328 patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2015;8:241–53.

Jensen TM, Saha K, Steinberg WM. Is there a link between liraglutide and pancreatitis? A post hoc review of pooled and patient-level data from completed liraglutide type 2 diabetes clinical trials. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1058–66.

Nauck MA, Frossard JL, Barkin JS, et al. Assessment of pancreas safety in the development program of once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist dulaglutide. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:647–54.

Mentz RJ, Bethel MA, Gustavson S, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients enrolled in the Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering (EXSCEL). Am Heart J. 2017;187:1–9.

Steinberg WM, Buse JB, Ghorbani MLM, et al. Amylase, lipase, and acute pancreatitis in people with type 2 diabetes treated with liraglutide: results from the LEADER randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:966–72.

Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of participants in the Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial on the cardiovascular effects of dulaglutide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:42–9.

Storgaard H, Cold F, Gluud LL, Vilsbøll T, Knop FK. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and risk of acute pancreatitis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:906–8.

Monami M, Nreu B, Scatena A, et al. Safety issues with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer and cholelithiasis): data from randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1233–41.

Bethel MA, Patel RA, Merrill P, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6:105–13.

Liu Y, Tian Q, Yang J, Wang H, Hong T. No pancreatic safety concern following glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist therapies: a pooled analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34:e3061.

Pinto LC, Rados DV, Barkan SS, Leitao CB, Gross JL. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, pancreatic cancer and acute pancreatitis: a meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:782.

Henry RR, Klein EJ, Han J, Iqbal N. Efficacy and tolerability of exenatide once weekly over 6 years in patients with type 2 diabetes: an uncontrolled open-label extension of the DURATION-1 study. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18:677–86.

Byetta (exenatide) [prescribing information]. Wilmington, DE; AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; 2015.

Bydureon (exenatide extended release) [prescribing information]. Wilmington, DE; AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP; 2015.

Acknowledgements

The analysis was performed by Ming Zhou, PhD. Andres Gomez, PhD, MPH, Ming Zhou, PhD, Sudeep Kundu, PhD, and Bridget Schmitz, PhD, of Bristol-Myers Squibb provided input on early drafts of the manuscript. Mary Beth DeYoung, PhD, of AstraZeneca critically reviewed the first draft of the manuscript. Peggy Lynch of AstraZeneca provided assistance with data management.

Funding

The analyses were supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb (Lawrenceville, NJ, USA) and AstraZeneca (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Article processing charges were funded by AstraZeneca. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing Assistance

Elizabeth Strickland, PhD, CMPP, and Amanda L. Sheldon, PhD, CMPP, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare (Philadelphia, PA, USA), provided medical writing support, which was funded by AstraZeneca.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the analyses, the interpretation of the data, provided critical review of all drafts, and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Disclosures

Kristina Johnsson is an employee of AstraZeneca. Elise Hardy is an employee of AstraZeneca. Nayyar Iqbal is an employee of AstraZeneca. Marion L. Vetter was an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb during the time of the original studies and is currently an employee of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson. Hui Wang was a consultant to AstraZeneca at the time of the studies and is currently a consultant to Fisher Clinical Research Institute.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study involves only analysis of previously published data and contains no new data from human participants. Therefore, informed consent and approval by an Institutional Ethics Committee was not required. All subjects consented and ethics approvals were obtained for the original data collection as part of the original clinical trials.

Data Availability

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8035517.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Vetter, M.L., Johnsson, K., Hardy, E. et al. Pancreatitis Incidence in the Exenatide BID, Exenatide QW, and Exenatide QW Suspension Development Programs: Pooled Analysis of 35 Clinical Trials. Diabetes Ther 10, 1249–1270 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0627-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-0627-1