Abstract

Aliphatic polyesters poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and foam plastic have been shown to be biodegradable by microorganisms, which possess cutinolytic enzymes. Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09, showed both high growth and enzyme activity on Yeast malt (YM) medium fed with PCL film than on YM medium. The hydrolytic enzyme activity of the culture on p-nitrophenyl butyrate indicated the occurrence of cutinase enzyme. This activity was confirmed by the degradation of PCL film which reached to the maximum (93.33 %) at 15 days and the degradation of foam plastic which reached 43.2 % at 30 days. These results suggest that the extracellular cutinase enzyme of Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 may be useful for the biological degradation of plastic wastes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastics become the essential ingredients to provide a quality due to their versatility. These are now rival metals in breadth of use and in severity of applications because of their flexibility, toughness, excellent barrier and physical properties and ease of fabrication (Seymour 1971; Andrady et al. 1998; Meenakshi et al. 2002; Fang and Fowler 2003; Orhan et al. 2004). The growing amount of plastic waste is generating more and more environmental problems worldwide. To overcome this problem, the biodegradation of plastics has been subjected to extensive studies during the past three decades. Biodegradation of plastics is seen by many as a promising solution to this problem as it is environmentally-friendly. Some types of plastics have been shown to be biodegradable by microorganisms which produce enzymes. Those biodegradable plastics such as aliphatic polyesters (polycaprolactone, PCL) which are used mainly in thermoplastic polyurethanes, resins for surface coatings, adhesives for shoes and synthetic leather and fabrics, also serve to make stiffeners for shoes and orthopaedic splints, and fully biodegradable compostable bags, sutures and fibres. The chemical structure of a PCL trimer is similar to two cutin monomers, which are inducer for cutinase activity. This knowledge was helpful to find microorganisms which are able to degrade PCL (Premraj and Doble 2005). Although numerous studies (El-Shafei et al. 1998; Howard 2003; Nishida and Tokiwa 1993; Tokiwa et al. 2009) have been reported on the biodegradation of different types of plastics, the published literature on the biodegradation of plastic foams appears to be scarce. Foam biodegradation is carried out by the enzymes associated with some microorganisms like bacteria and fungi (Gautam et al. 2007).

Recently, a special focus has been given to the endophytic microorganisms that live inside the plant tissue without causing any immediate, overt effects (Hirsch and Braun 1992). Endophytes are known to produce bioactive natural products, which offer an enormous potential for exploitation for medicinal, agricultural and industrial uses (Tan and Zou 2001; Zhang et al. 2006). Special concerns are given to endophytic yeasts isolated from different plants (Larran et al. 2001, 2002; Cao et al. 2002; Tian et al. 2004; Nassar et al. 2005; Xin et al. 2009). Among them, smut yeast-like fungi of the genus Pseudozyma have attracted considerable attention as producers of enzymes (Pandey et al. 1999). Seo et al. (2007) reported that Pseudozyma jejuensis is able to degrade plastics waste. However, very few information is available so far about the biochemical activity of endophytic Pseudozyma spp.

Although PCLs have been shown to be degraded by enzymes secreted by a number of bacteria (Benedict et al. 1983), little studies have been done using yeast. A new yeast strain isolated recently from the medicinal plant Hyoscyamus muticus in our laboratory was identified as a novel species of the genus Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09, (Abdel-Motaal et al. 2009). Evaluation of the PCL and foam plastic biodegradation by this new species was the objective of this study.

Materials and methods

Fungal strain and media

The yeast strain Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09, from Hyoscyamus muticus (Egyptian henbane) was isolated as a new species of the genus Pseudozyma.

Yeast culture and PCL films, foam plastics degradation assay

The Pseudozyma strain was grown on the yeast malt agar (YMA) (glucose 1.0 % w/v, peptone 0.5 % w/v, yeast extract 0.3 % w/v, malt extract 0.3 % w/v, agar 2.0 % w/v), and the plates were incubated for 2 days at 25 °C. A single colony of yeast species was inoculated into 5 ml of YM broth and cultured at 30 °C. After 24 h, 1 ml of culture broth was inoculated into 1,000-ml flask contain 50 ml YM broth and incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm over night. Sterilized dry PCL film of known weight was added to each culture in addition to positive control (YM broth culture of each Pseudozyma species without PCL film) and negative control (YM broth with PCL film only). Flasks were incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 200 rpm for 15 days. Three replicas from each flask have been done considering the different time intervals (3, 5, 8, 12 and 15 days) to study the degradation behaviour. Under the same conditions, foam plastics were incubated in yeast culture but for longer time (30 days). The PCL films and foams were taken out carefully in different intervals time, washed thoroughly by double distilled water to remove any media components or yeast cells if present on the their surface and were completely vacuum dried at 30 °C over night. The percentage of weight loss was recorded.

Culture turbidity

Growth rate of yeast culture incubated with and without PCL films and foams was measured and assayed according to the culture turbidity (OD600nm).

pH values

Effect of variable pH values on the growth rate, protein concentrations and enzyme activity have been studied.

Preparation of polycaprolactone (PCL) film and market’s foam plastic

Poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL) with molecular weight 70,000–100,000 Da was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. PCL film was prepared in small glass petri dishes (3 cm) by dissolving polymer in acetone and left for air drying. The prepared PCL films and the 1 cm quadrate cutting foams (polystyrene with molecular weight 100,000–400,000 Da) were weighed and sterilized in 80 % ethanol for 2 min, well dried and then kept under UV lamp for 30 min and fed into the pre-grown yeast cultures.

Cutinolytic enzyme assays

Spectrophotometric assay was used to determine the cutinase activity with p-nitrophenyl butyrate (PNB; Sigma, ST Louis, MO, USA) and p-nitrophenyl palmitate (PNP; Sigma, ST Louis, MO, USA) as substrates (Kim et al. 2003).

96-well microplate was used for the hydrolysis reactions at 30 °C for 4 min. Each well contained 200 μl of an enzyme/substrate solution (solution A), comprising 106.7 μl of phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.0), 13.3 μl of Triton X-100 (4 g l−1), 13.3 μl of cell-free culture broth and 66.7 μl of substrate (PNB or PNP) solution. The PNB and PNP solutions were prepared with variable concentrations ranging from 0 to 1,000 mg l−1. The initial velocity [i.e. the initial maximum rate of change in absorbance (∆OD405nm s−1)] was measured using a Molecular Devices EMax 96-well microplate reader (MDS Analytical Technologies, Toronto, Canada), and the enzyme-free solution A was used as a blank. As the eight wells in each of the 12 columns of the 96-well microplate contained an equal content of enzyme and substrate, the eight initial velocities measured for each column were used to calculate an average initial velocity for a specific reaction condition, resulting in an SD <5 %.

Protein assay

Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford method using Bio-Rad reagent (Bradford 1976).

Results and discussion

Condition favouring the degradation of polycaprolactone

The rate of degradation of biodegradable plastics is controlled not only by their chemical structure but also by environmental conditions such as temperature (Kitamoto et al. 2011). The yeast strain Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 showed the best growth rate and degradation percentage of polycaprolactone (PCL) and foam plastics in yeast malt broth media at 30 °C and at pH 6 with shacking at 200 rpm. Maximal activity of the PNB and PNP was found in the same conditions.

Enzyme activity of Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09

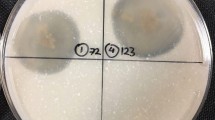

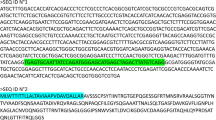

Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 showed higher growth on YM medium fed with PCL film than on YM medium (Fig. 1). The substrate-specific hydrolysis and high accessibility to PNB are intrinsic properties of cutinase that have never been observed for hydrolysis by lipases and esterases (Kim et al. 2003). Isolation of natural cutinase from variable microbial sources would be easy using this distinct characteristic. The hydrolytic activities of cell-free supernatant from Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 culture broth on twop-nitrophenyl esters (PNB and PNP) were estimated for a range of substrate concentrations on time courses. The hydrolytic activities are defined as the initial maximum rate of hydrolysis at each substrate concentration as described previously (Kim et al. 2003; Seo et al. 2007). On the time course, the hydrolytic enzyme activity of the culture on PNB rapidly increased after 3 days and the maximum activity was at day 5. The initial maximum rate of PNB hydrolysis in YM and PCL medium was higher than that in YM medium (Fig. 2), whereas the hydrolytic activity on PNP was very low with the same range of substrate concentrations, even in YM and PCL medium. Therefore, it is likely that the cutinase production by Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 was induced by PCL. These results are similar to those obtained by Kim et al. 2003, Seo et al. 2007 using Pseudozyma jejuensis OL71.

During growth of Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 culture broth, the protein concentration rapidly increased after 3 days with a maximum concentration at 5 days similar to enzyme activity. Protein concentration recorded higher concentration in PCL feed YM medium than that in PCL free YM medium (Fig. 3).

PCL degradation by Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09

PCL dimers and trimers, products of enzymatic PCL degradation, are structurally similar to cutin degradation products that are known to be inducers of cutinase activity. This implies that oligomers of PCL may be natural inducers and substrates of cutinase (Nishida and Tokiwa 1993).

In the present study, PCL degradation was achieved in the conditions favouring the yeast strain’s growth in the YM medium in Erlenmeyer flasks as described above for 15 days. The weight loss of the degraded film was recorded and compared as a function of time. Under those conditions, partial degradation of PCL film (26.88 %) was recorded at the third day of incubation. That degradation reached to the maximum (93.33 %) at the 15 days (Figs. 4, 5). Weight loss was negligible in the same medium but free yeast cells (Figs. 4, 5). In an early study (Oda et al. 1995) isolated five strains of filamentous fungi of which Paecilomyceslilacinus was able to degrade 10 % of PCL after 10 days incubation. Xu et al. (2007) investigated the ability of several stock bacterial strains to degrade PCL. After 30 days of incubation, the weight loss of PCL film by the strain Lysinibacillus sp. 70,038 was 9 % while other strains showed less weight loss degradation.

Foam degradation by Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09

During the growth of Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 in YM medium fed with foam disc for 30 days, the extracellular culture broth secretion exhibited an ability to degrade the foam disc. The loss weight percentage of the foam disc within 30 days incubation time was 43.2 % (Fig. 5). This ability was slower as compared to PCL degradation but it is promising for the biodegradation of foam since foams are considered to be highly resistant to biodegradation when compared with other types of synthetics plastics (Gautam et al. 2007). An increase in molecular weight results in a decline of polymer degradability by microorganisms. High molecular weights result in a sharp decrease in solubility making polymers unfavourable for microbial attack due to difficulties of the substrate to be assimilated through the cellular membrane and then further degraded by cellular enzymes. The breakdown of large polymers to carbon dioxide (mineralization) requires several different organisms, with one breaking down the polymer into its constituent monomers, one able to use the monomers and excreting simpler waste compounds as by-products and one able to use the excreted wastes. Our yeast strain is capable of being one in a potential series of microbial strains used for degradation of plastic foam.

Conclusions

Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 as a new yeast species exhibited high ability to degrade PCL and foam plastic. The hydrolytic activities of cell-free supernatant of Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 culture broth on twop-nitrophenyl esters (PNB and PNP) and its high accessibility to PNB are intrinsic properties of cutinase production. Further detailed studies of the enzymes produced by Pseudozyma japonica-Y7-09 to degrade other types of plastics are currently being undertaken, and the results of these will be important for the development of new technological processes for the biodegradation of plastic pollutants.

References

Abdel-Motaal FF, El-Zayat SA, Kosaka Y, El-Sayed MA, Nassar MS, Ito S (2009) Four novel ustilaginomycetous anamorphic yeast species isolated as endophytes from the medicinal plant Hyoscyamus muticus. Asian J Plant Sci 8(8):526–535

Andrady AL, Hamid SH, Hu X, Torikai A (1998) Effects of increased solar ultraviolet radiation on materials. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 46:96–103

Benedict CV, Cameron JA, Huang SJ (1983) Polycaprolactone degradation by mixed and pure cultures of bacteria and a yeast. J Appl Polym Sci 28:335–342

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254

Cao LX, You JL, Zhou SN (2002) Endophytic fungi from Musa acuminate leaves and roots in South China. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:169–171

EI-Shafei H, EI-Nasser NHA, Kansoh AL, Ali AM (1998) Biodegradation of disposable polyethylene by fungi Streptomyces species. Polym Degrad Stab 62:361–365

Fang J, Fowler P (2003) The use of starch and its derivatives as biopolymer sources of packaging materials. Food Agric Environ 1:82–84

Gautam R, Bassi AS, Yanful EK (2007) A review of biodegradation of synthetic plastic and foams. Appl Biochem Biotech 1:85–108

Hirsch GU, Braun U (1992) Communities of parasitic microfungi. In: Winterhoff W (ed) Handbook of vegetation science: Fungi in vegetation science, vol 19. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp 225–250

Howard GT (2003) Biodegradation of polyurethane: a review. Int Biodeter Biodegrad 40:245–252

Kim YH, Lee J, Moon SH (2003) Uniqueness of microbial cutinases in hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl esters. J Microbiol Biotechnol 13:57–63

Kitamoto HK, Shinozaki Y, Cao X, Morita T, Konishi M, Tago K, Kajiwara H, Koitabashi M, Yoshida S, Watanabe T, Sameshima-Yamashita Y, Nakajima-Kambe T, Tsushima S (2011) Phyllosphere yeasts rapidly break down biodegradable plastics. AMB Express 29:1–44

Larran S, Monaco C, Alippi HE (2001) Endophytic fungi in leaves of Lycopersicon esculentum mill. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 17:181–184

Larran S, Perello A, Simon MR, Moreno V (2002) Isolation and analysis of endophytic microorganisms in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) leaves. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:683–686

Meenakshi P, Noorjahan SE, Rajini R, Venkateswarlu U, Rose C, Sastry TP (2002) Mechanical and microstructure studies on the modification of CA film by blending with PS. Bull Mater Sci 25:25–29

Nassar AH, El-Tarabily KA, Sivasithamparam K (2005) Promotion of plant growth by an auxin-producing isolate of the yeast Williopsis saturnus endophytic in maize (Zea mays L.) roots. Biol Fertil Soil 42:97–108

Nishida H, Tokiwa Y (1993) Distribution of poly(-hydroxybutyrate) and poly(-caprolactone) aerobic degrading microorganisms in different environments. J Environ Polym Degrad 1:227–233

Oda Y, Asari H, Urakami T, Tonomura K (1995) Microbial degradation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and polycaprolactone by filamentous fungi. J Ferment Bioeng 80(3):265–269

Orhan Y, Hrenovic J, Buyukgungor H (2004) Biodegradation of plastic compost bags under controlled soil conditions. Acta Chim Slov 51:579–588

Pandey A, Benjamin S, Soccol CR, Nigam P, Krieger N, Soccol VT (1999) The realm of microbial lipases in biotechnology. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 29:119–131

Premraj R, Doble M (2005) Biodegradation of polymers. Ind J Biotechnol 4:186–193

Seo H, Um H, Min J, Rhee S, Cho T, Kim Y, Lee J (2007) Pseudozyma jejuensis sp. nov., a novel cutinolytic ustilaginomycetous yeast species that is able to degrade plastic waste. FEMS Yeast Res 7:1035–1045

Seymour RB (1971) Additives for polymers, introduction to polymer chemistry. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, pp 268–271

Tan RX, Zou WX (2001) Endophytes: a rich source of functional metabolites. Nat Prod Rep 18:448–459

Tian XL, Cao LX, Tan MH, Zeng GQ, Jia YY, Han WQ, Zhou SN (2004) Study on the communities of endophytic fungi and endophytic Actinomycetes from rice and their antipathogenic activities in vitro. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 20:303–309

Tokiwa Y, Calabia BP, Ugwu CU, Aiba S (2009) Biodegradability of plastics. Int J Mol Sci 10:3722–3742

Xin G, Glawe D, Doty S (2009) Characterization of three endophytic, indole-3-acetic acid-producing yeasts occurring in Populus trees. Mycol Res 113:973–980

Xu S, Yamaguchi T, Osawa S, Suye S (2007) Biodegradation of poly(6-caprolactone) film in the presence of Lysinibacillus sp. 70038 and characterization of the degraded film. Biocontrol Sci 12(3):119–122

Zhang HW, Song YC, Tan RX (2006) Biology and chemistry of endophytes. Nat Pro Rep 23:753–771

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kazunobu Matsushita (Yamaguchi University) for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdel-Motaal, F.F., El-Sayed, M.A., El-Zayat, S.A. et al. Biodegradation of poly (ε-caprolactone) (PCL) film and foam plastic by Pseudozyma japonica sp. nov., a novel cutinolytic ustilaginomycetous yeast species. 3 Biotech 4, 507–512 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-013-0182-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-013-0182-9