Abstract

People tend to think that they know others better than others know them (Pronin et al. in Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 639–656, 2001). This phenomenon is known as the “illusion of asymmetric insight.” While the illusion has been well documented by a series of recent experiments, less has been done to explain it. In this paper, we argue that extant explanations are inadequate because they either get the explanatory direction wrong or fail to accommodate the experimental results in a sufficiently nuanced way. Instead, we propose a new explanation that does not face these problems. The explanation is based on two other well-documented psychological phenomena: the tendency to accommodate ambiguous evidence in a biased way, and the tendency to overestimate how much better we know ourselves than we know others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

On another possible reading of Pronin et al.’s discussion of the introspection illusions, they do no seek to explain the illusion of asymmetric insight in terms of the introspection illusion, but rather seek to explain both of these illusions in terms of the knowability illusion. However, even if this is the correct interpretation, our new explanation still provides a unified account of all three illusions, by providing an independent explanation of the illusion of asymmetric insight, which in turn explains the other two.

See Vazire (2010) for further discussion of motivational limitations to self-knowledge.

See, e.g., Nisbett and Wilson (1977) for a classic study.

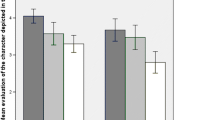

These effects are illustrated in Figure 1 (Pronin et al. 2001: 644).

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for bringing this effect to our attention.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for urging us to consider this.

References

Andersen, S.M., and L. Ross. 1984. Self knowledge and social inference: I. The impact of cognitive/affective and behavioral data. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 46: 280–293.

Carruthers, P. 2008. Cartesian epistemology: Is the theory of the self-transparent mind innate? Journal of Consciousness Studies 15 (4): 28–53.

Carruthers, P. 2010. Introspection: Divided and partly eliminated. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 80: 76–110.

Gilovich, T. 1991. How we know what isn’t so. New York: The Free Press.

Gilovich, T., and L. Ross. 2015. The wisest one in the room: How you can benefit from social psychology’s most powerful insights. New York: The Free Press.

Goffman, E. 1959. The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor Books.

Gopnik, A. 1993. How we know our minds: The illusion of first-person knowledge of intentionality. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 16 (1): 1–14.

Greenberg, J., T. Pyszczynski, and S. Sheldon. 1982. The self-serving attributional Bias: Beyond self-presentation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 18 (1): 56–67.

Greenwald, A. 1980. The totalitarian ego. American Psychologist 35: 603–618.

Ichheiser, G. 1949. Misunderstandings in human relations: A study in false perception. American Journal of Sociology 55 (Suppl): 1–70.

Jones, E., and R. Nisbett. 1972. The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the cause of behavior. In Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior, ed. E. Jones, D. Kanouse, H. Kelley, R. Nisbett, S. Valins, and B. Weiner, 79–94. New York: General Learning Press.

Kennedy, K., and E. Pronin. 2008. When disagreement gets ugly: Perceptions of Bias and the escalation of conflict. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 34 (6): 833–848.

Kozuch, B., and S. Nichols. 2011. Awareness of unawareness. Folk psychology and introspective transparency. Journal of Consciousness Studies 18 (11–12): 135–160.

Kunda, Z. 1990. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin 108: 480–498.

Lord, C., L. Ross, and M. Lepper. 1979. Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37: 2098–2109.

Lun, J., S. Kesebir, and S. Oishi. 2008. On feeling understood and feeling well: The role of interdependence. Journal of Personality 42 (6): 1623–1628.

Markus, H. 1983. Self-knowledge: An expanded view. Journal of Personality 51: 543–565.

Mezulis, A., L. Abramson, J. Hyde, and B. Hankin. 2004. Is there a universal positivity Bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychological Bulletin 130 (5): 711–747.

Nisbett, R., and T. Wilson. 1977. Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological Review 84: 231–259.

Oishi, S., S. Akimoto, J. Richards, and E. Suh. 2013. Feeling understood as a key to cultural differences in life satisfaction. Journal of Research in Personality 47 (5): 488–491.

Oswald, M., and S. Grosjean. 2004. Confirmation bias. In Cognitive illusions. A Handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgment and memory, ed. R. Pohl, 79–98. New York: Psychology Press.

Pronin, E. 2009. The introspection illusion. In Advances in experimental social psychology, ed. M. Zanna, vol. 41, 1–67. Cambridge: Academic Press.

Pronin, E., and M. Kugler. 2007. Valuing thoughts, ignoring behavior: The introspection illusion as a source of the bias blind spot. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (4): 565–578.

Pronin, E., J. Kurger, K. Savitsky, and L. Ross. 2001. You don’t know me, but I know you: The illusion of asymmetric insight. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81: 639–656.

Pronin, E., D. Lin, and L. Ross. 2002. The Bias blind spot: Perceptions of bias in self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 28 (3): 369–381.

Pronin, E., T. Gilovich, and L. Ross. 2004. Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: Divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others. Psychological Review 111 (3): 781–799.

Pronin, E., J. Fleming, and M. Steffel. 2008. Value revelations: Disclosure is in the eye of the beholder. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96: 795–809.

Riess, M., P. Rosenfeld, V. Melburg, and J. Tedeschi. 1981. Self-serving attributions: Biased private perceptions and distorted public descriptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 41 (2): 224–231.

Ross, L., and A. Ward. 1996. Naive realism in everyday life: Implications for social conflict and misunderstanding. In Values and knowledge, ed. T. Brown, E. Reed, and E. Turiel, 103–135. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Schlenker, B., and R. Miller. 1977. Egocentrism in groups: Self-serving biases or logical information processing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 35 (10): 755–764.

Vazire, S. 2010. Who knows what about a person? The self-other knowledge asymmetry (SOKA) model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98: 281–300.

Wason, P. 1960. On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 14: 129–140.

Wilson, T., and E. Dunn. 2003. Self-knowledge: Its limits, value, and potential for improvement. Annual Review of Psychology 55: 1–26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Steglich-Petersen, A., Skipper, M. Explaining the Illusion of Asymmetric Insight. Rev.Phil.Psych. 10, 769–786 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-019-00435-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-019-00435-y