Abstract

In this paper we argue that formal exchanges with poor consumers in emerging markets are hard to create and maintain, resulting in widespread market failure. More specifically, in emerging markets the institutions required for exchange either function poorly or are entirely absent, making it difficult for sellers to deliver affordable and accessible offerings to poor buyers in a financially sustainable manner. The marketing challenge thus becomes (1) developing a viable business model to facilitate market-based exchanges and (2) shaping the institutions needed to implement this business model. Drawing on institutional theory and extending it with insights from the marketing and business model innovation literatures, we develop a model of exchange in emerging markets. At the heart of our model is the idea that sellers often need to act as institutional entrepreneurs in order to create and deliver value when marketing to the poor in emerging markets. We discuss the implications of our model for future research on marketing, exchange and emerging economies, as well as the implications for managers seeking to market to the poor in emerging economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Marketing is the “social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating and exchanging products and values with others.” Kotler et al (2008).

“As emerging markets evolve from the periphery to the core of marketing practice, we will need to contend with their unique characteristics and question our existing practices and perspectives, which have been historically developed largely in the context of industrialized markets.” Sheth (2011)

At its core, marketing is the study of how firms create and maintain exchanges with customers (Bagozzi 1974, 1975; Hunt 1983; Houston and Gassenheim 1987; Vargo and Lusch 2004). Several decades of research have resulted in an impressive body of knowledge about how marketers should and do create and maintain such exchanges. Almost all of this knowledge, however, is based either implicitly or explicitly on a study of marketing in developed economies. Very little work has examined how firms create and capture value in emerging economies and virtually no work examines how this is done among the poorest segments of those economies (see Viswanathan et al. 2010).

Yet, over 2.5 billion people—nearly half the world’s population—live on less than $2 a day. Our understanding of how to market to the majority of the world’s inhabitants is negligible, and the field of marketing is impoverished by its lack of knowledge about such issues of macro importance (see Mick 2007). Moreover, marketing to the poor in emerging markets poses significant challenges that do not exist in developed economies (see Mahajan and Banga 2006; Wu 2013). For instance, the institutions required for the creation and maintenance of exchanges are often non-existent or fragmented in emerging markets (Khanna and Palepu 2000). Specifically, these markets frequently lack the institutions that help with assessing customer preferences (e.g. market research firms that specialize in poor segments) and responding to customer preferences (e.g. the absence of a distribution and sales infrastructure that reaches the poor) (Prahalad 2010). The attempt to create and maintain exchanges with the poor in emerging economies therefore requires a different approach to marketing than in developed economies (see Pauwels et al. 2013).

In this paper, we develop a model to examine the creation and maintenance of exchanges with the poor in emerging economies. To do so, we first explore why marketing to the poor in emerging markets entails a unique set of challenges relative to marketing in developed economies. We then argue that responding to these unique challenges (e.g. the lack of institutions that facilitate formal exchange) requires the creation of new business models that deliver an attractive value proposition to poor consumers in a financially viable and sustainable manner. Finally, we show how implementing such business models requires institutional entrepreneurship, namely working with existing institutions to create an environment that enables the business model and hence exchange to succeed. In sum, we show that marketers facilitate exchange in emerging economies by molding and re-molding existing fragmentary institutions or creating new institutions to deliver a value proposition in a financially viable manner.

Given the relative newness of the phenomenon we are studying and the lack of marketing theory in this area, our focus in this paper is on initiating theory development rather than assessing, enhancing or testing theory (Bansal and Clelland 2004; Cohen and Dean 2005; see Darden 1991). As such, following Yadav (2010) we employ multiple strategies for such theory development. Specifically, bringing institutional theory to bear on the phenomenon of creating and facilitating exchange with the poor in emerging markets enables us to draw analogies, invoke theory types, exploit interrelations, and move to new levels of analysis in order to spur theory development. Institutional theory is an established conceptual approach in sociology and organization science that has been applied to a range of social and technological contexts but seldom explicitly to exchanges involving the world’s poor (see Battilana and Dorado 2010; Tracey and Phillips 2011). However, as we show below, by combining institutional theory with existing knowledge in marketing and innovation, we are able to shed a great deal of light on the phenomenon of exchange with the poor. In particular, adopting an institutional lens allows us to consider the buyer-seller dyad in the context of the broader social processes within which innovation and exchange take place, thus helping us to draw analogies, exploit interrelations and incorporate multiple levels of analysis in our theorizing.

By building a framework that is designed to increase our understanding of marketing to the poor in emerging markets, we make three main contributions. First, we extend existing marketing theory to include a wider set of conditions, namely those that exist among poor segments in emerging economies. While a small number of marketing scholars have begun to consider the distinctive challenges of marketing in emerging markets (e.g., Baker 2009; Viswanathan et al. 2010), our understanding of marketing in this context remains limited. In developing our arguments, we respond to calls for more conceptual work in marketing and for marketing to broaden its relevance (see Kohli 2009; Yadav 2010).

Second, we develop and integrate with marketing theory the concepts of business model innovation and institutional entrepreneurship to build a more systemic and strategic view of marketing. These concepts and their accompanying theorizing have become central to the fields of strategy and organization theory, enabling those fields to engage with important issues of relevance to businesses worldwide (see Garud et al. 2002; Maguire et al. 2004; Zott and Amit 2008; Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Teece 2010; Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010; Thompson and MacMillan 2010; Tracey et al. 2010). By engaging with these concepts and building on them from a marketing viewpoint, we respond to calls by leading marketers for a focus on strategic and macro rather than merely tactical elements of marketing theory and methods (see Reibstein et al. 2009; Kumar 2004; Vargo and Lusch 2004; Varadarajan 2010; Day 1992; Mick 2007). We also hope, in the process, to forestall the ceding of terrain to cognate disciplines like strategy and organization theory, especially in areas that fall squarely within the purview of marketing.

Third, our framework has practical implications for firms seeking to engage poor consumers in emerging economies. Given the large numbers of such consumers, and their increasing ability and desire to consume, makes them attractive customer segments to serve. Yet, marketing to these segments also present firms from both developed and emerging economies with some severe difficulties. Specifically, while multinationals from developed economies stand to gain new sources of revenue from marketing to the poor in emerging markets, they also face significant challenges due to their relative lack of knowledge of such segments (Prahalad 2010). Conversely, while domestic firms from emerging economies have a relative advantage in terms of knowledge about these segments, they face equally significant challenges in scaling up their solutions to achieve a profitable scale and scope (Anderson et al. 2010). This paper therefore has the potential to help marketers of both types of firms to overcome the challenges they face in creating and capturing value in emerging economies.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, we briefly introduce the concepts of business models and business model innovation before setting out a framework for studying exchange in emerging markets. We employ this framework to examine market failures and the challenges involved in creating and maintaining exchanges with the poor in emerging economies. Next, we develop an institutional model of exchange with the poor in emerging economies. And we conclude with a discussion of the implications of our model for research and practice.

Business model innovation

The rise of digital technologies and e-commerce has made it necessary for managers and academics to rethink traditional ways of doing business. This in turn has led to the coining of the concept of a business model, described by Osterwalder et al. (2005) as a “blueprint” for how to run a business. While there is still some dispute regarding how exactly to define a business model, there is general agreement that business models: 1) are a new unit of analysis that span beyond the firm, 2) provide a more holistic approach to describing how a firm does business and 3) focus on both creating and capturing value (see Zott et al. 2011).

Further, the literature on business models is broadly concerned with two issues. First, it is concerned with how firms use business models to create and capture value. The focus here is on how new technologies require a change in how the business is run in order to enable the creation and capture of value from customers (for example, see Mahadevan 2000; Amit and Zott 2001; Daft and Lewin 1993). Second, the literature is concerned with how the business model itself drives organizational innovation. The key question here is how business model innovation can drive organizational change and renewal, generate new sources of competitive advantage and lead to better performance (see for example Mitchell and Coles 2003).

Most of the growing literature on business models and business model innovation is based on business in developed markets. In developed economies, market based exchanges are generally supported by well-functioning financial, legal and social institutions, all of which facilitate such exchanges. The literature is, however, generally silent on how these concepts apply (or not) to emerging markets. Indeed, for reasons we elaborate on below, we argue that the existing literature is less applicable to firms operating in emerging markets. Specifically, emerging markets differ from developed markets in two important ways. First, they are characterized by a large proportion of their populations living and working in the informal economy: this means that most consumers have low incomes, typically earn and spend on a daily basis, and operate beyond the reach of formal institutions such as banks and courts. Second, emerging markets either lack or have poorly functioning institutions that facilitate market based exchanges. The combination of large numbers of informal economy consumers and poorly functioning institutions means that emerging economies are often characterized by market failures in core areas such as energy, health, education and finance. Thus, firms that operate in emerging markets face particular challenges in creating and capturing value through market based exchanges. We argue, therefore, that the nature of the business models needed to succeed in emerging markets differs from those in developed economies. We also argue that the process by which firms develop and implement these business models differs from the process needed in developed economies.

In the next section, we focus on the causes of market failure in emerging markets. We use this as a basis to develop a theoretical model of how firms can implement business model innovations to overcome these market failures and create viable exchanges particularly with the low-income consumers that form the majority of customers in emerging markets. In this context, we define business model innovation as finding a way to deliver an attractive value proposition to poor consumers in a financially viable and sustainable manner (see Prahalad 2010; Anderson and Markides 2007; Anderson et al. 2010). Specifically, this involves innovations in how the firm generates revenues while managing its costs.

Exchange in emerging markets: a model of exchange and market failures

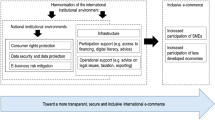

We draw on existing research in marketing to develop a general framework for the study of exchange (see Fig. 1). In identifying the key elements in the process of exchange we distinguish between focal and contextual elements. The focal elements of exchange include the seller, the buyer, and the offering itself (the marketing mix). The contextual elements include the institutions (both formal and informal) that potentially facilitate (or hinder) exchanges between sellers and buyers. These include financial institutions such as banks; social institutions such as family, clan or caste; cultural institutions such as social norms and practices; legal institutions such as the protection of property rights; and marketing institutions such as market research agencies, and distribution and sales agents.

We use this general framework to understand the conditions needed for exchange to take place between sellers and buyers from poor segments of emerging markets. Specifically, we examine a condition that particularly marks such exchanges: namely, market failure. We discuss details of this condition to show how marketing to poor segments in emerging economies differs from marketing to consumers in more developed economies.

Market failure among the poor in emerging markets

A distinguishing feature of the economic life of poor consumers in emerging economies is the prevalence of market failure for even basic needs such as financial services, energy and healthcare. For instance, some 2.2 billion adults in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East have no access to formal banking facilities (Chaia et al. 2009). Similar numbers of people live without access to the electricity grid and therefore do not benefit from regular sources of lighting and energy (Tanaka et al. 2010). Consequently, poor consumers have to rely on informal sources to supply these needs, leading to sub-optimal outcomes such as irregular supply, poor quality of supply or high prices (see Hammond et al. 2007).

We define market failure as a situation in which there is inefficient allocation of goods and services in a market (see Ledyard 2008). This means that there exist other forms of exchange which would leave buyers better off than the existing forms of exchange. But what explains this kind of market failure on a grand scale in emerging markets? More specifically, why do formal market exchanges for so many essential goods and services fail to occur among poor consumers in emerging economies? Drawing on the framework above, we argue that such market failure could be due to factors that operate on either the demand or supply side, involving both focal and contextual elements of exchange. See Tables 1 and 2 for details of causes of market failures for the examples discussed in this paper.

Demand side reasons for market failure

Assuming that the need for basic services such as finance, energy and healthcare exists, there are three main reasons for market failure from the point of view of buyers: lack of awareness, lack of accessibility and lack of affordability (see Prahalad 2010; Anderson and Markides 2007; Anderson et al. 2010; Kashyap and Raut 2006; Mahajan 2008; Mahajan and Banga 2006).

First, buyers may not be aware of the existence of a market offering that better satisfies their needs or how an existing market offering is used. Given the relative lack of marketing institutions such as media and advertising services targeted at these segments, poor consumers are likely to be relatively uninformed about the range of existing market solutions. Although the rapid spread of satellite television coupled with the longstanding prevalence of radio services among the poor mean that awareness is becoming less of a hindrance to exchange, it is certainly more difficult for poor consumers in emerging economies to learn about possible market solutions than their counterparts in developed economies. An example of this can be seen in India where 27% of all deaths occur with no medical attention at the time of death (Sivakumar 2015). This is to a great extent because the poor are unaware of services they can avail themselves of in a medical emergency. For instance, they are very unlikely to be aware of an emergency number to call, partly because there is the lack of a national equivalent to a 911 facility. Further, the poor often associate ambulance services with the transportation of deceased patients rather than with medical care which might prevent death, and therefore often avoid calling ambulance services (see Johar and Harries 2010).

Second, even if poor consumers are aware of market offerings to satisfy their needs, they might not be able to access such solutions easily (Mahajan and Banga 2006). For example, in the case of banks, the relative lack of infrastructure often means that bank branches are few and far between in the rural areas where the bulk of the world’s poor live (see Basu and Srivastava 2005). The lack of accessibility also affects the healthcare industry. India, for instance, has 20 million blind people, of whom 80% are visually impaired due to curable cataracts. This in turn is because two thirds of the country’s eye care infrastructure is concentrated in urban areas, leaving rural areas (where the majority of the population lives) without access to adequate eye care (see Chaudhary et al. 2012; Rangan 2009; Karamchandani et al. 2009).

Finally, even if poor consumers are aware of better market offerings and are able to access them, they might not be able to afford such offerings. In the case of financial services, for instance, the monthly management fee that poor consumers must pay to keep a bank account open might not justify the potential benefits of such a service (see Dupas and Robinson 2010). Or again, in East Africa, because accessing electricity from the grid is often impossible, large parts of the population are forced to spend 20% of their income on kerosene solely for lighting (Crainer 2013; Aglionby 2016).

Taken together, the relative lack of institutions in emerging markets that enable exchange are likely to result in poor consumers frequently being unable to enter into formal exchanges with sellers of market offerings.

Supply side reasons for market failure

From the viewpoint of suppliers, there are three main reasons for market failure in exchanges involving poor consumers in emerging markets: lack of awareness of a given market opportunity, lack of the means to reach poor consumers, and the lack of an economical means of initiating and fulfilling exchange with such consumers (Prahalad 2010; Anderson and Markides 2007; Anderson et al. 2010; Kashyap and Raut 2006; Mahajan 2008; Mahajan and Banga 2006).

First, sellers might not be aware of the market opportunity for their offerings among poor consumers. Given the relative lack of marketing institutions such as market research agencies that specialize in these segments, sellers may have limited knowledge of the nature and extent of the market opportunity offered by poor consumers in emerging markets. In the absence of thorough market research, sellers all over the world fall victim to the typical myopia of assuming (all) consumers are like themselves. Foreign multinationals, for instance, often talk to only a few people in the emerging markets they are entering, because they incorrectly believe that those few people represent the entire country or are aware of major developments in it. In Mexico, for example, 34% of the population lives in poor quality housing. CEMEX, the country’s largest producer of building materials, realized that this segment represented a large proportion of their end-users with whom they had never directly interacted and who they therefore knew very little about. In order to reach this large untapped market, the company had to invest heavily in market research to better understand the needs of this segment (see Segel et al. 2006; London and Lee 2006; London et al. 2012).

Second, even if sellers are aware of the market opportunity, they might not be able to reach these consumers easily. The remoteness of many of the world’s poor from urban centers, combined with the relative lack of distribution and sales infrastructure in emerging economies, means that reaching poor consumers is likely to be very difficult if not impossible in many cases. In Asia and Africa, multinational firms in sectors like fast moving consumer goods face a huge supply chain challenge in reaching the upwards of 50% of the population that lives in remote rural areas. In India, for instance, Unilever faces the twin challenge of poor transport infrastructure and over 300,000 small villages dispersed across the country; taken together these challenges make traditional supply chain structures economically unviable (see Rangan and Rajan 2007).

Finally, even if sellers are aware of market opportunities among poor consumers and are able to reach them, they might not be able to do so in an economical way. The cost of conducting market research on such consumers, developing a solution to meet their needs, and delivering this solution to remote locations might be higher than the likely returns from such exchanges. Going back to eye care in India, the World Bank estimates that over $200 million is needed yearly to expand and build eye care infrastructure to the required level. Even large multinationals often do not have the financial resources needed to reach out to poor consumers in a financially viable manner (see Chaudhary et al. 2012; Rangan 2009; Karamchandani et al. 2009).

Taken together, the relative lack of institutions that enable exchange with poor consumers in emerging markets is likely to mean that sellers are frequently unable or unwilling to enter into such exchanges, resulting in market failure.

Business model innovation in emerging markets

Given the significant barriers to exchange that exist on both the demand and supply sides of the buyer-seller dyad, the question then arises as to how, if at all, exchanges involving poor consumers in emerging markets might be facilitated. How, for instance, might a persistent firm or entrepreneur overcome such barriers to enable these exchanges to occur? We argue that initiating and fulfilling exchanges with poor consumers in emerging markets requires business model innovation, namely finding a way to deliver an attractive value proposition to poor consumers in a financially viable and sustainable manner (see Prahalad 2010; Anderson and Markides 2007; Anderson et al. 2010). We now discuss examples of companies that corrected market failures in emerging markets through business model innovation (see Table 3 for a summary of all business model innovations discussed in the paper).

Business model innovation to address market failure due to affordability

Aravind Eye Hospitals offer an example of business model innovation focused on addressing the challenge of preventable blindness in India (see Prahalad 2010). The key obstacle that the founder of the hospital network, Dr. Govindappa Venkataswamy, faced was the high cost of starting and operating such hospitals, which in turn made them unaffordable to most consumers. To overcome these obstacles Dr. Venkataswamy reinvented the cataract surgery business model. Instead of using a cost-based approach to pricing, he set the price of his service based on the economic stratum of the community he served: those who could afford the full price, paid it; those who couldn’t, got the service at a reduced rate or even free. He then worked backwards from what people could pay to focus on ways of reducing the cost structure to fit the average price.

To reduce the cost structure, he focused on one main type of surgery, namely cataract surgery: the main cause of blindness in India. This allowed him to focus on reducing fixed costs through reproducibility (i.e. standardizing the process to reduce the core skills and discretionary elements needed). This in turn allowed him to reduce surgery time from 30 min to 10 min. Further, he found ways to ensure that the level and quality of surgery received by paying versus non-paying customers was the same. For instance, by having doctors rotate between paying and non-paying wards, he ensured that the quality of surgery did not vary across patients. Aravind’s business model innovation can therefore be summarized as: 1) the adoption of the assembly line approach (i.e. high volumes, low margins) to cataract surgery and 2) pricing the service based on the economic stratum of the consumer. Finally, it is worth noting that the market failure in this example, caused by the lack of government resources, has been solved through business model innovation on the part of a private enterprise.

Business model innovation to address market failure due to lack of awareness

As previously noted, 34% of Mexico’s population faces a housing deficit. Homes for this large section of the population are often either incomplete or poorly built. CEMEX, Mexico’s biggest producer of building material, realized that the people affected by this housing deficit were end users of CEMEX products, and yet the company knew almost nothing about them. To address this issue, CEMEX issued a “Declaration of Ignorance” to publicly acknowledge their limited knowledge and to initiate actions to remedy the problem. In 1998, CEMEX launched an initiative called Patrimony Hoy (“Personal Property Today” in Spanish) which began by conducting extensive market research to better understand customer behaviors and needs (see Segel et al. 2006; London and Lee 2006; London et al. 2012).

There were two key findings of this research. First, poor consumers often just lack the financial means to access adequate building material. Second, even when poor families were able to afford some of the building materials needed, they often faced unexpected financial hardship that forced them to halt the building process, leading to degradation and waste of the purchased materials due to lack of adequate storage facilities.

In response to the first finding, CEMEX innovated and changed their business model to better serve and meet the needs of their poor customers. They developed a product that gave poor families direct access to building materials as well as technical support. They also gave families access to different financing plans, ranging from micro-credit to micro-saving, based on their needs and income. In response to the second finding, CEMEX also offered families access to storage facilities, in case they ran into financial difficulties and needed to pause the project for a period of time.

In order to make the business model financially viable, CEMEX had to think about sustainable revenue streams and cost reduction mechanisms. The company’s sustainable revenue stream came from the service fees they charged the customer, which were often covered by the different financing schemes offered to the customer. In order to drive down costs CEMEX had to negotiate new deals with distributers participating in the program (see Segel et al. 2006; London and Lee 2006; London et al. 2012).

Business model innovation to address market failure due to the inaccessibility of poor consumers

Over 70% of consumers in India live in villages dispersed all over the country. Given the poor transportation infrastructure in India, reaching these consumers is not only costly but also difficult using traditional supply chain structures. To address this challenge, Unilever India developed a new business model titled Project Shakti. The project focused on driving down the cost of long, complex supply chains, by providing female entrepreneurs in rural India with access to micro-credit that they could use to purchase Unilever products to sell in their villages. This project not only reduced the cost of reaching poor consumers in rural villages, it also created employment for thousands of Shakti entrepreneurs whose income was doubled as a result. The key challenge in making this business model work was pricing the products at a level that guaranteed a high enough margin to keep the Shakti entrepreneurs motivated, while at the same time not causing conflict with other channel members (see Rangan and Rajan 2007).

While finding a viable business model is crucial, equally important is implementing the business model to facilitate and maintain exchange over the long term (Anderson and Markides 2007; Anderson et al. 2010). Because of the fragmented nature of the institutional environment, however, implementing new business models in emerging markets is likely to require institutional entrepreneurship – the purposive reshaping of existing institutions or the creation of new ones – on the part of sellers. Specifically, to create and facilitate exchange in emerging economies, marketers need to work with the existing institutional context to forge a set of institutional arrangements that allows them to deliver a value proposition in a financially viable and sustainable manner. We now turn to a detailed discussion of the role of institutional entrepreneurship in facilitating the implementation of business model innovation, and hence exchange, in the context of marketing to the poor in emerging economies.

Exchange in emerging markets: an institutional perspective

In this section we start by drawing on organization theory to build a set of institutional arguments (see Dacin et al. 2002; DiMaggio and Powell 1991; Greenwood et al. 2008) designed to explain how sellers introduce fundamentally new business models in an emerging market context. We then introduce in turn the three phases of our proposed institutional model of exchange (see Fig. 2), with reference to a variety of examples, to show how businesses have engaged in institutional entrepreneurship in order to implement business model innovations that addressed or fixed a market failure of the emerging market in which the firm was operating (see Table 4 for a summary of all examples). And finally, we use the example of solar lighting solutions to provide a comprehensive illustration of how our institutional model of exchange functions in practice.

Implementing business model innovation: an institutional perspective

Institutional theory was originally concerned with the ways in which institutions constrain behavior and promote organizational conformity to dominant norms and practices. Over the last two decades, however, institutional analysis has become increasingly concerned with explaining institutional change, with a particular focus on the role of firms and other actors in manipulating the institutional context in which they operate (e.g., Garud et al. 2002; Greenwood and Hinings 1996; Hargadon and Douglas 2001).

The notion of institutional entrepreneurship – the “activities of actors who leverage resources to create new institutions or to transform existing ones” (Maguire et al. 2004 p. 657) – has had an especially significant impact on the institutional literature, providing a powerful conceptual tool for researchers seeking to understand the role of strategic choice in institutional change. Institutional entrepreneurs might be individuals (Tracey et al. 2010), firms and other types of organization (Garud et al. 2002), or groups of individuals and/or organizations such as social movements (Hiatt et al. 2009). The key issue, however, is that these actors have a set of strategic objectives that they seek to achieve by altering the institutional arrangements in which they are embedded. The term institutional work is used to describe the particular strategies institutional entrepreneurs use when seeking to create, maintain or disrupt existing institutional arrangements in order to achieve a particular objective (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006).

These theoretical developments have underpinned the emergence of a significant body of research designed to explain how firms are able to influence their environments and engage in innovation. In this paper, we adapt this work to explain how sellers implement business model innovation in emerging markets in order to create and maintain formal exchanges with the poor. Our basic argument is that sellers need to operate in an institutional context that enables them to deliver a value proposition in a financially viable and sustainable manner. However, given the nature of emerging markets outlined above, sellers may be unable to do so within existing institutional configurations. This means that to innovate in this context sellers may have to engage in deliberate action designed to strategically engender changes in their institutional environment. In other words, a ‘solution’ to the problems of poorly functioning markets in emerging economies may be for sellers to act as institutional entrepreneurs.

We develop a model (see Process of Institutional Change in Fig. 2) that builds on prior work from institutional theory in its interface with the technology management literature (see Van de Ven and Garud 1993; Van de Ven et al. 1999, 2000a, b; Garud et al. 2003; Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006). Drawing on a key part of this body of work (Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006), our model comprises four institutional change processes – which we consider as four distinct types of institutional work – that institutional entrepreneurs need to engage in to affect institutional change. (1) Framing: frames are shared interpretive schemes or systems of meaning that help actors make sense of the world and provide templates for organizing (McAdam et al. 1996), (2) network construction, which is a political process characterized by competition and co-operation between the relevant actors in a given institutional setting (see Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006). (3) enactment of institutional arrangements, which entails working with powerful state and other regulatory actors in order to create or enact the formal and informal institutions necessary for a given business model innovation to become viable, and (4) legitimation through collective action processes, where legitimation involves proving that the business model works by getting consumers and other stakeholders committed to the new form of exchange and ensuring that the resources needed to sustain the model continue to flow toward it.

An institutional model of exchange in emerging markets

We will now introduce our institutional model of exchange (see Fig. 2) in which we argue that the process of creating and maintaining exchanges with poor consumers in emerging markets unfolds in three phases. In phase 1 buyers and sellers operate in a situation of market failure in which exchange is inefficient, partial or non-existent. In phase 2 sellers implement the four steps discussed above (framing, network construction, enactment of institutional arrangements and legitimation through collective action) to implement their business model by working to bring about the institutional change needed to support it. And finally phase three is a result of the successful implementation of the proposed business model which leads to buyers and sellers operating in a situation in which formal exchange occurs and a formal market exists. We will now discuss each of the three phases in more detail with examples illustrating the theoretical concept.

In phase 1, buyers and sellers operate in a situation of market failure in which exchange is inefficient, partial or non-existent. This is largely because the institutions needed to facilitate exchange are non-existent or fragmentary. To create the conditions for exchange, sellers need to develop a business model that delivers value for buyers in a financially viable and sustainable way.

Take Kenya’s banking and remittance industry as an example. In 2006, the industry was characterized by market failure leading to insufficient exchange: 74% of the population was unbanked and 85% of the population was sending remittances using informal and unsafe methods (for instance, a commonly used method was sending cash with friends, family or even complete strangers such as bus drivers). This led to a number of problems: money would not be delivered on time, or bus drivers might charge extensive fees for the transfer, or the money would get lost on the way without the sender or receiver having any way of holding the courier to account. The only safe alternative available at that time was Western Union, which used to charge up to 40% transfer fees, making this service expensive and unaffordable.

To address and fix the market failure and to create a better environment for exchange, Nick Hughes, head of Global Payment Solutions at Vodafone, developed M-PESA (M- for mobile and Pesa being Swahili for money): a service that allowed customers of Safaricom (Vodafone’s subsidiary in Kenya) to deposit and transfer money using their mobile phones. The value delivered to customers was that the service offers an affordable, safe and accessible mode of money transfer and remittance. The service also proved to be economically viable: it increased the company’s market share and revenues and built strong customer loyalty. Further, Hughes was able to reduce cost by 1) using a vast network of independent agents (often “mom and pop” retailers) to cash the money, 2) using big data to guarantee a sustained cash flow to the agents’ network and 3) raising 50% of the initial capital investment needed from DFID (Britain’s aid agency) (see Chandy and Duke 2011; Jack and Suri 2014; Sadoulet and Furdelle 2014).

In Phase 2, sellers implement the business model by working to bring about the institutional change needed to support it. This process requires sellers to frame the problem and solution appropriately; construct networks that facilitate the implementation of the business model; enact institutional arrangements to put in place the regulations, resources, demand and proprietary activities needed to support the business model; and achieve legitimacy for the business model to ensure that it is sustainable in the long run. We now discuss the specific steps that institutional entrepreneurs like Nick Hughes go through to implement and guarantee the success of their business model innovation.

Phase 2: step 1: framing

The first type of institutional work that sellers in emerging markets need to engage in when seeking to implement innovative business models is framing. Frames are shared interpretive schemes – or systems of meaning – that help actors make sense of the world and provide templates for organizing (McAdam et al. 1996). Stable institutional contexts are characterized by dominant collective action frames, which are taken for granted by the constituent actors in that context. However, institutional entrepreneurs can challenge dominant frames through the development of strategically constructed alternatives. This involves institutional entrepreneurs critiquing current institutional arrangements and specifying their shortcomings, then proposing an alternative set of arrangements that challenge these shortcomings.

For example, the entrepreneurial firm trying to sell solar lighting solutions to the rural poor in India (see Miller 2009) first had to challenge a dominant frame which assumed that the lighting needs of those off the electricity grid could only be met by the state or aid agencies investing large amounts of money in expanding the central grid. This firm then needed to propose an alternative arrangement that involved small-scale, decentralized solutions such as those involving solar technology, i.e. a new business model. Further, while the selling of solar technologies in developed economies typically involves an appeal to sustainability and “green” agendas, the entrepreneurial firm in India found such framing to be less effective in the context of its target market. Instead, the firm found that its discourse had to be primarily centered on the fundamental need for affordable lighting solutions and only secondarily about the sustainability benefits of solar technology (see Miller 2009).

Institutional entrepreneurs need to engage in three main framing tasks when seeking to alter a particular system of meaning (Benford and Snow 2000). The first task is diagnostic framing, which involves the articulation of a particular problem and an attempt to identify the causes of that problem. In the context of selling solar lighting to the rural poor in India, this required the entrepreneur to identify and highlight the huge unmet need that those off the electricity grid have for affordable lighting, along with the fact that expanding the grid to reach 600,000 Indian villages was not a viable solution, even over the medium to long term (Miller 2009).

The second task is prognostic framing, which involves articulating a potential solution to the problem that has been identified, and proposing a specific strategy or set of strategies for how the solution might be implemented. There is clearly a close relationship between diagnostic and prognostic framing; thus “the identification of specific problems and causes tends to constrain the possible ‘reasonable’ solutions and strategies advocated” (Benford and Snow 2000, p. 616). In the context of selling solar lighting to the rural poor in India, prognostic framing meant that the entrepreneurial firm had to propose a solution built around a de-centralized strategy in which households off the grid are able to generate their own power rather than rely on expensive and unlikely outcomes such as the expansion of the electricity grid (Miller 2009). Identifying the unworkable nature of a centralized solution (expanding the electricity grid through large government investment) at least partially enabled the entrepreneurial firm to come up with a decentralized solution to the problem.

The third core framing task is motivational framing. This provides the rationale or justification for a particular course of action through which institutional entrepreneurs can galvanize support and convince others to commit time and effort toward a particular goal. Here the outline of a clear mission combined with a workable business model become crucial. Again, in the case of selling solar lighting solutions, the company selling the solution made it its mission to prove 1) that poor people could afford sustainable technology and 2) that the company could make a profit from selling such technology to the poor (Miller 2009).

Nick Hughes used diagnostic, prognostic and motivational framing to convince the top management of Vodafone’s HQ in the UK to invest approximately $3 million into M-PESA. VF’s management had two main objections to the mobile money solution: 1) M-PESA was too far from Vodafone’s core business (i.e., voice and data) and 2) VF’s top management wanted to see return on investment in the short run to justify the high initial capital investment required. Both objections are typical of a firm like Vodafone that is accountable to a large number of stakeholders and needs to justify to them any risk that the company is taking. However, this mindset and way of operating was the biggest obstacle in the way of M-PESA and could have killed the idea very early on.

Despite this, Nick Hughes decided to continue to pursue his idea and change the institutional arrangements standing in his way. Instead of depending on Vodafone to finance 100% of the project, Hughes legitimized his idea by securing 50% of the required funding from DFID (the UK’s international aid agency) and asking Vodafone to match this funding. DFID as an institution operates with a different mindset: because they have a better understanding of emerging markets, they understand the time it might take for such a project to be implemented and show a return on investment.

Securing the DFID funding helped Hughes with diagnostic framing in the sense that it showed Vodafone’s top management that Hughes’ articulation of the problem was accurate, that the idea was promising and that the problem lay in their short term focus. It also helped in prognostic framing in the sense that securing the DFID funding solved half the problem and showed Vodafone that the M-PESA idea was legitimate. This in turn motivated Vodafone’s top management to agree to fund the remaining 50% of the project and to give Nick Hughes more time to show results. At the time, Nick Hughes was a pioneer in looking for funding from an aid agency for the implementation of a new business idea (see Chandy and Duke 2011; Jack and Suri 2014; Sadoulet and Furdelle 2014).

Phase 2: step 2: network construction

The second type of institutional work that sellers must perform when implementing business model innovation in emerging markets is network construction. Most studies of institutional entrepreneurship show that it is a political process characterized by competition and co-operation between the relevant actors in a given institutional setting (see Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006). For example, Levy and Scully (2007, p. 985) describe institutional entrepreneurs as “Modern Princes” who use their skills to create networks in order to “outmanoeuvre dominant actors with superior resources”. Similarly, Wijen and Ansari (2007) note that institutional entrepreneurship poses a “collective action problem” in which actors need to balance their own individual interests with co-operation, while at the same time guarding against actors who seek to free-ride on the efforts of others.

While some studies have focused on institutional entrepreneurs with obviously dominant positions (e.g. Hoffman 1999), others have focused on the ways in which actors with apparently marginal positions have helped to shape new institutional configurations (e.g. Hensmans 2003; Maguire et al. 2004). Regardless of their relative power and the nature of their resources, however, all institutional entrepreneurs are required to construct strategic networks to achieve their objectives.

The role of networks is particularly significant in the context of exchange with the poor in emerging markets (Anderson and Markides 2007; Anderson et al. 2010). The absence of existing institutions that facilitate distribution and after sales service, as well as the lack of institutions that ensure consumer education and protection, mean that sellers in these markets must develop an ecosystem of partners to help make their products and services accessible and acceptable to consumers (see Mahajan 2008; Mahajan and Banga 2006). Given the remoteness of these consumers, it is often the case that marginal rather than dominant actors have a major role to play in the creation and functioning of these networks. The importance of networks holds for a range of industries, including fast moving consumer goods, cellular phones and financial services.

In financial services, many different forms of microfinance have involved the creation of a network of self-help groups (Yunus et al. 2010). Each self-help group is itself a network of like-minded women without access to credit who pool their resources to invest, lend to and borrow from each other. Moreover, fast moving consumer goods manufacturers like Unilever now engage with networks of such self-help groups to distribute their products to remote consumers in an efficient and cost effective way (see Rangan and Rajan 2007). Indeed, working with microfinance institutions provides Unilever with access to self-help groups and their members. Under such arrangements, individual members of self-help groups may take loans from their group to buy material from Unilever which they then sell on to consumers in their local communities, thus acting as semi-formal members of a Unilever “retail” network. Finally, cellular phone service providers in emerging markets, such as Safaricom in Kenya or Bharti Airtel in India, have over time worked with a large number of “mom-and-pop” retailers to create a vast retail network that serves consumers in far-flung rural communities (see Prahalad and Mashelkar 2010). The successful adoption of mobile telephony in emerging markets has been largely a consequence of the development and use of such distribution networks.

Phase 2: step 3: enactment of institutional arrangements

Sellers often need to work with powerful state and other regulatory actors in order to create or enact the formal and informal institutions necessary for a given business model innovation to become viable. This may involve deliberately creating conflict between existing institutional structures and processes.

The institutional infrastructure needed for creating and implementing innovation typically comprises four building blocks (see Hargrave and Van de Ven 2006; Van de Ven and Garud 1993; Van de Ven et al. 1999). The first is institutional regulations. These are the rules created by the government agencies, trade bodies and technical communities that regulate a given product or technology, whose approval is required for its introduction. These actors must be persuaded to support the innovation and put the necessary formal institutional arrangements in place if it is to be viable. For instance, in selling financial services to the unbanked poor in emerging markets, a key challenge for sellers has been influencing central banks such as the Reserve Bank of India or Central Bank of Kenya to enable non-banking entities such as cellular phone operators to provide financial services like mobile payments without using the intermediation of banks (see The Economic Times 2008).

Often, the approval and support of these regulatory bodies is what makes or breaks a business model in an emerging market. To illustrate the importance of such institutional regulations, consider two emerging markets, Kenya and Egypt, where regulatory arrangements made all the difference for the success of mobile payment services. After a short but intense battle with the Central Bank of Kenya, Safaricom managed to gain their support and approval for the launch of M-PESA in 2007. The Central Bank of Kenya interfered very little in determining the number of agents allowed to work for M-PESA, as long as certain security measures such as “know-your-customer” conditions were guaranteed. The vast network of agents enabled by this approach was a key factor in the success of M-PESA in Kenya. In Egypt, on the other hand, the regulator capped the number of agents allowed per mobile operator at 2000, with very strict criteria governing who could be an agent; this in turn led to a concentration of agents in Egypt’s main cities, severely limiting the spread and success of the service (see Chandy and Duke 2011; Jack and Suri 2014; Sadoulet and Furdelle 2014).

The second building block is resource endowments, which comprise the basic knowledge required to develop the product and the pool of human resources needed for the business model to function effectively, as well as the appropriate financial mechanisms required to fund the development costs of the new business model. For instance, selling financial services to the unbanked poor in Bangladesh required the Grameen Bank to select and train service personnel to promote, distribute and serve a dispersed and relatively uneducated customer base (Yunus et al. 2010). It also required the Grameen Bank to work with investors to secure the finances needed to put such operations in place (Yunus et al. 2010). Given the relatively untested nature of such markets, securing these resources can be a particularly difficult and drawn out process (see Miller 2009).

In the case of M-PESA, one of the challenges that Nick Hughes faced with his new business model was a cash-flow bottleneck. Hughes realized that the flow of remittances was for the most part from urban to rural Kenya, which meant that the agents in urban areas had a cash surplus, while agents in rural areas suffered from a cash deficit. Leveraging his operations background, Hughes developed a sophisticated network of cash distribution between agents according to their needs and location. This step was essential in securing the necessary resources to guarantee the smooth running and success of the business model (see Chandy and Duke 2011).

The third building block is consumer demand, which for “new to the world” business models does not pre-exist; institutional entrepreneurs are required to raise awareness and stimulate demand for their products. In the case of introducing banking to the unbanked, convincing poor consumers – who earn and spend on a daily basis – of the benefits of saving and of paying a monthly fee for the privilege of doing so, is not a trivial exercise (Dupas and Robinson 2010). Educating these consumers and changing their existing patterns of behavior to create the necessary demand requires strategic action on the part of entrepreneurial actors and involves considerable resources, time and effort.

The fourth building block is proprietary activities which allow institutional entrepreneurs to capture value and create a commercially viable venture through business model innovation. Particularly important in this respect is the creation of complementary assets such as manufacturing, marketing and distribution. Again, in the context of bringing financial services to the unbanked poor, once sellers have persuaded these consumers to open a bank account, they then face the significant challenge of deepening consumers’ use of financial services. Enabling such consumers to ascend the financial ladder and move from savings to more sophisticated financial instruments such as loans and insurance after initial adoption requires a great deal of organization, effort and resources (Yunus et al. 2010). For example, it requires a salesforce that manages relationships with customers, constantly encouraging them to extend their existing custom while also cross-selling new services to them.

Phase 2: step 4: legitimation through collective action processes

Having framed the ‘problem’ and proposed a possible ‘solution’ in the form of a new business model, constructed a network to lobby in favor of that solution, and enacted an appropriate set of formal and informal institutional structures within a given emerging market to support it, the final type of institutional work required of sellers is the legitimation of the new business model through collective action. Thus while framing, network construction and institutional enactment lay the groundwork for the actual implementation of the business model, legitimation helps secure the long term sustainability of the model. Specifically, legitimation involves proving that the business model works by getting consumers and other stakeholders committed to the new form of exchange and ensuring that the resources needed to sustain the model continue to flow toward it.

Legitimacy is a foundational concept in institutional theory. While researchers have identified many different kinds of legitimacy, we focus on two core types: namely cognitive and sociopolitical legitimacy (see Aldrich and Fiol 1994). Cognitive legitimacy refers to the level of public knowledge about a new product, service or process. When actors in a given institutional context accept an activity as ‘taken for granted’ and no longer question its existence, the activity is said to have high levels of cognitive legitimacy. In the context of microfinance, for instance, once the basic model was shown by the Grameen bank to work in Bangladesh, terms such as micro-credit, self-help group, and Grameen entered the vocabulary of policymakers and investors worldwide (see Pearl and Phillips 2001).

Sociopolitical legitimacy refers to the extent to which key actors such as government officials and legislators, public figures, opinion leaders and the media openly endorse and support a new product, service or process. In the context of microfinance, if it began to achieve sociopolitical legitimacy when the World Bank and venture capitalists started to invest large sums on such schemes worldwide (see Pearl and Phillips 2001), then this process reached its apotheosis when Mohammed Yunus and Grameen Bank were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006. Cognitive and sociopolitical legitimacy are clearly closely related: institutional entrepreneurs need to build levels of public knowledge and then gain the support of powerful actors if they are to become legitimate and thus highly institutionalized. With respect to microfinance, this symbiotic relationship between the two types of legitimacy has clearly existed from the start; for instance, the interest and behavior of investors and policymakers have clearly influenced the opinions of the media and general public, and vice versa.

Legitimacy is closely linked to various positive performance outcomes (Bansal and Clelland 2004; Cohen and Dean 2005; Hannan and Carroll 1992; Pollock and Rindova 2003). Specifically, legitimacy has been shown to improve the likelihood of organizational survival and resource acquisition (Stuart et al. 1999). In the context of microfinance, the bank that Yunus started in 1976 by lending $27 to a group of families in a village has now become a billion-dollar micro-credit venture with more than eight million borrowers in Bangladesh alone.

In the case of M-PESA the service gained cognitive legitimacy 12 months after its launch when its active subscriber numbers increased by 30.6%, its subscriber market share was estimated at 79% and revenue market share was estimated at 83%. Additionally, the service spread beyond Kenya’s boundaries: other mobile operators invested and tried to implement the service in countries like Tanzania, Uganda and Afghanistan (see Chandy and Duke 2011; Jack and Suri 2014; Sadoulet and Furdelle 2014). Yet, the success of M-PESA in Kenya was unprecedented. Replications often failed due to barriers in implementing one or more of the 4 steps of the institutional model of exchange described above (e.g., enacting institutional arrangements in Egypt).

M-PESA gained a clear form of socio-political legitimacy once whole new business models started to be based on the service, as when micro-finance institutions started to integrate mobile payments into their business models in order to reduce the costs of collecting payments (Jack and Suri 2014; Sadoulet and Furdelle 2014). Nick Hughes himself subsequently founded M-Kopa, a provider of solar lighting solutions in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. The business model of M-Kopa is only possible because it leverages mobile payments to enable unbanked customers to pay off the up-front costs of solar lighting equipment using micropayments in instalments.

Finally, in Phase 3, buyers and sellers operate in a situation in which formal exchange occurs and a formal market exists. Buyers are aware of the seller’s offering and are able to afford and access it, while sellers are able to deliver the offering in a financially sustainable manner, thus ensuring that the conditions for exchange to happen are met.

Overall, the example of M-PESA in Kenya allows us to see in detail how an institutional entrepreneur like Nick Hughes might navigate the four stages of our proposed institutional model of exchange, altering the realities he initially faced, which were often obstacles in his way. Hughes successfully managed to turn around the remittance industry in Kenya from a market failure to a market success, while at the same time changing the nature and business model of the telecom industry more generally.

Our proposed institutional model of exchange in emerging markets can help organizations devise and implement successful business model innovations to tackle some of the most pressing market failures faced by our societies today. In order to demonstrate the practical and theoretical insights that the model affords – which have been suggested by the examples threaded through the foregoing discussion – the next section examines one case in depth: how a solar lighting company in India brought about change and gave thousands of households access to clean energy (see Miller 2009).

An illustration of the institutional model of exchange: the case of solar lighting

In order to provide a more comprehensive illustration of our proposed Model (see Fig. 2), consider again the case of selling solar lighting solutions to the rural poor in India (see Miller 2009). In the mid-1990s (Phase 1), the market for such solutions did not exist despite a large unmet need: while large numbers of poor consumers were off the electricity grid, formal exchanges for alternative energy solutions were rare if not nonexistent. On the buyer side, three major factors accounted for this market failure: lack of affordability, availability and awareness. On the seller side, the major reason for market failure was the challenge of delivering an affordable and accessible solar lighting solution in a financially viable and sustainable way.

The first step for the seller wishing to create such a market was to develop a business model that found a way around these obstacles to exchange. A potential business model that would achieve this involved creating a network of local entrepreneur-distributors who would use a bank loan guaranteed by the seller to buy the solar equipment and batteries; these local entrepreneurs would use the equipment to charge the batteries which would then be rented on a daily basis to end consumers. With such a model, the local entrepreneurs absorbed the capital cost of the equipment and made the solution affordable to end consumers, most of whom earned and spent money on a daily basis. The local presence of these entrepreneurs also ensured that the solution was available and accessible to end consumers, and provided an opportunity to increase awareness.

While elegant as a potential solution, actually implementing this business model was a far greater challenge because the institutions needed for its implementation were fragmentary or nonexistent. Thus, in Phase 2 (1995–2005), the seller had to do a great deal of institutional work to shape the institutions needed to implement the business model and to create and facilitate exchange. First, the seller had to frame the challenge and the proposed solution. This involved making the case to relevant stakeholders that the energy needs of those off the electricity grid could not be achieved by existing centralized, on-grid solutions, but would instead require decentralized, off-grid solutions involving new technologies such as solar. Framing also involved outlining a business model, like the one above, that would make such a solution possible in a financially sustainable way.

Second, implementing the business model required working to create the necessary networks needed to make the business model viable. The major step here was selecting, training and financing a network of local entrepreneurs who would act as intermediaries between the seller and end consumers. As described above, the proper selection, training and financing of these entrepreneurs ensured the affordability, accessibility and awareness needed to make the business model work.

Third, implementing the business model required a process of institutional enactment whereby the seller could secure the resources and formal contracts needed to finance the business model and make it financially sustainable. This in turn required working with banks to convince them to lend money to people (micro-entrepreneurs) who lacked a credit history in a sector in which the banks lacked prior investment experience (i.e. energy and solar technologies).

Finally, implementing the business model required gaining legitimacy among important stakeholders such as investors, government officials, public figures and opinion leaders. Achieving such legitimacy in turn required sustained interaction, negotiation and communication with these stakeholders to not only ensure that the business model was successfully implemented but also to ensure that this success was recognized and celebrated in various quarters.

Phase 2, namely the process of institutional work needed to implement the business model in this context, was difficult and time consuming and took over 10 years of sustained effort to realize. It was only after this process was completed that the market entered Phase 3. Specifically, it was only around 2005 that the conditions needed for a large number of formal exchanges to take place in this sector were finally met and a proper market came into existence for solar lighting solutions for the rural poor. Indeed, by 2005–2006 the seller had installed more than 100,000 solar lighting systems and generated sales of $3 million despite the fact that two-thirds of the firm’s customers lived on less than $4 per day. Moreover, a number of other players had entered the market, further establishing the legitimacy of the sector and ensuring its viability in the long run (Miller 2009).

Discussion and conclusion

We have developed a model designed specifically to understand exchange with poor consumers in emerging economies. To do so, we have integrated institutional theory with research in marketing and innovation to conceptualize sellers to the poor in emerging markets as institutional entrepreneurs who are required to (1) develop new business models and (2) shape the institutional environment in order to implement these business models. The institutional model of exchange that we have presented has several implications for research and practice, which we discuss in detail below.

Implications for theory

By focusing on how sellers create and maintain exchanges with buyers, we extend the existing marketing theory of exchange in a more strategic and macro direction. While exchange has rightly been identified as a key aspect of marketing (see Bagozzi 1974, 1975; Hunt 1983; Houston and Gassenheim 1987; Vargo and Lusch 2004), the progress of a theory of exchange has faltered, perhaps because marketing scholars have adopted a neutral focus between buyers and sellers in their theorizing about exchange. Specifically, institutions and the role of the seller (i.e., the marketer) in purposefully shaping these institutions to facilitate exchange have seldom been the focus of systematic analysis in marketing. Yet, as our model elaborates, the seller has a key role to play in making markets, especially in emerging economies. First, it is the seller who develops a given business model that creates and captures value for buyers. Second, perhaps more importantly, it is the seller who shapes the institutional context that enables the successful implementation of that business model. Extending marketing theory along these lines ensures that the market-making role of marketers is better understood and emphasized. It also helps ensure that marketing continues to engage with strategic and macro rather than merely tactical business issues, and does not cede important conceptual terrain to cognate fields such as strategy and organization theory on topics that are so obviously core to marketing as a field (see Reibstein et al. 2009; Kumar 2004; Varadarajan 2010; Day 1992; Mick 2007).

Our model also extends existing marketing theory to an economically vital context that is rarely studied by marketing researchers, namely exchange involving poor consumers in emerging markets. By doing so, we call attention to a central characteristic of such contexts, namely market failure, and shed light upon when and why exchange happens (and when and why it does not).

Studying such a context not only broadens the range of phenomena to which marketing theory applies, it also enriches what we know about more mainstream contexts such as marketing to middle to high income consumers in developed economies. Indeed, from a historical perspective, now-developed economies were once emerging economies. Specifically, even these countries, in earlier phases of their development, faced institutional voids that resulted in market failure. However, because most modern business research in general, and marketing research in particular, has been conducted in the developed economies of North America and Western Europe, our theories have not typically incorporated the role of institutions in facilitating market exchanges. It is only now that business and marketing researchers are beginning to study emerging markets that the crucial role of institutions and how they are built is coming into view. Further, it is also true that some sectors of even developed economies lack appropriate or adequate institutions to facilitate market exchanges. “Emerging sectors” such as drones, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, etc., are all so new that regulations and other market-facilitating institutions are yet to be formulated even in the West. Moreover, even as these institutions are being created in the West, their creation has to contend with the existence of legacy institutions designed for prior, now outdated technological regimes. The new regulations frequently come up against existing, outdated regulations making change hard.

It is here that emerging markets offer interesting new possibilities, even for developed economies. Emerging markets, because they are often creating technological infrastructure from scratch can leapfrog the West in this process, not only in terms of the physical aspects but also in terms of the regulatory institutions. For instance, many emerging economies leapfrogged straight to mobile telecommunications almost entirely by-passing a prior land-line phase. They are now also using the mobile infrastructure to leapfrog straight into mobile banking without passing through the bricks-and-mortar banking phase. It is entirely likely that many developing countries might create off-grid renewables infrastructures without ever reaching full electrification through a centralized grid. Emerging markets, in creating these technological infrastructures, have also been able to leapfrog developed economies in terms of creating regulatory backbones to support these new sectors. For instance, the Central Bank of Kenya was able to create a regulatory space for a non-banking entity (the mobile telecoms provider Safaricom) to provide financial services to unbanked Kenyan citizens. By applying an institutional model to emerging industries in developed economies, marketing theorists can begin to formulate a more general theory of exchange that applies across economic contexts and income segments. A particularly interesting line of enquiry in this regard concerns the relative importance of business model innovation and institutional change in emerging relative to developed economies.

Finally, our model highlights the type of work that marketers need to perform in creating and shaping the institutions needed to make exchange happen. The idea that marketers often act as institutional entrepreneurs has rarely been explored (for a recent exception see Humphreys 2010). In part this is because most marketing knowledge, whether academic or practical, has been built in the context of or applied to developed economies where the institutions needed to facilitate and maintain exchanges are typically well developed. By focusing on how exchange happens in a context where the institutions needed to facilitate exchange are fragmentary or non-existent we emphasize the importance of incorporating macro-level theorizing into marketing research. Marketing research is typically focused at a micro-level of analysis (i.e. the buyer-seller dyad). As a result, it often fails to take account of broader social processes as well as key stakeholders that are central to the exchange process, including actors in the financial, media and regulatory domains. Understanding how marketing managers interact with their environment and develop relationships with such stakeholders is arguably as important as understanding how marketing mangers interact and develop relationships with business customers and end consumers (see Kotler 1986).

Implications for method

The model we outline in this paper offers several methodological implications for marketing research. First, the complex, interdependent and emerging nature of the phenomena we study—exchanges with the poor, business model innovation and institutional entrepreneurship—suggest the need for significant grounded research into how market failure is overcome and formal exchange with the poor is created and maintained across geographical, sectoral and cultural contexts. This in turn suggests the need for deep ethnographies in order to build a more complete theory of exchange that not only examines the buyer side of the exchange equation (see Thompson et al. 2006; Fournier 1998; Holt 2002) but also that of the seller. The use of ethnographic techniques to understand seller rather than buyer behavior is a relatively undeveloped area of marketing methodologically (see Viswanathan et al. 2010; Gebhardt et al. 2006) and our model provides a framework to help guide such research.

Second, our model suggests significant opportunities for quantitative research into how markets for the poor are created and the impact that these markets have on the welfare of poor consumers. Specifically, given that business models for creating exchanges with the poor in fundamental areas such as energy, health, financial services and education are only just beginning to be implemented on a large scale (see Hammond et al. 2007), opportunities exist for marketing researchers to be present at the birth to conduct longitudinal field experiments that examine the impact of such offerings on the lives of the poor (see Levitt and List 2008). Such studies could shed light on how regulatory or technological shocks have facilitated exchange in emerging markets where formal exchanges did not exist before, and the moderating or mediating role of marketing in this process. Such quantitative studies, because they enable the researcher to be present from birth, and to compare outcomes in treatment relative to control groups in the field, offer the opportunity to make strong inferences about cause and effect in real environments (see Angrist and Krueger 2001). They thus leverage the internal validity of laboratory experiments with the external validity provided by the field setting. Such field experiments in emerging economies have been rare in marketing although they are gaining influence in areas such as development economics and finance (see Levitt and List 2008).

Finally, our model suggests the opportunity of combining quantitative and qualitative approaches by examining the role that language and discursive processes play in institutional work and exchange. Various aspects of institutional work such as framing and legitimacy require key actors to make creative use of language (Maguire et al. 2004; Phillips et al. 2004; Zilber 2006; Maguire and Hardy 2009). Shaping existing institutions and creating new ones often requires agents to persuade actors in a particular institutional setting to adopt a new system of meaning – a new way of thinking about a particular issue – which creates a shared sense of purpose and identity, and acts as a kind of social glue binding the key actors together. Understanding how this is done offers marketing researchers the opportunity to go beyond content analysis by venturing into areas such as psycholinguistics and discourse analysis in the study of market making (see Humphreys 2010; Yadav et al. 2007).

Implications for practice

In the next few decades, global economic growth will be driven by the emerging markets of Latin America, Africa and Asia (Mahajan 2008; Mahajan and Banga 2006). The growth of emerging markets will, in turn, be driven by the rise of the “next four billion” consumers as they make their way out of poverty into relative affluence (see Hammond et al. 2007). This large population of consumers offers huge opportunities for multinationals and domestic, large and small businesses alike. The model of exchange we develop suggests that managers of firms seeking to engage the poor in emerging markets would need to change at least three aspects of the way they go about the business of marketing.

First, our model suggests that firms seeking to make a profit from exchanges with the poor will need to think systemically about how they create and maintain exchanges with such consumers in emerging markets. Specifically, firms will need to think about all aspects of the business model needed to make such exchanges sustainable in the long run. This will require managers not only to think about the value proposition they offer to poor consumers but also about how they organize their operations in order to deliver this value proposition in a financially viable way. Further, delivering the value proposition will require systemic thinking around how to use 1) the product and price to deliver affordability to financially constrained consumers, 2) distribution to achieve availability and accessibility for widely dispersed markets, and 3) promotion to educate consumers with relatively low levels of awareness. Simply adopting existing practices developed for affluent consumers in developed economies will not work, given the significant differences in lifestyle and incomes between such consumers and those of the poor in emerging economies.

Second, our model suggests that implementing the business models needed to facilitate exchanges with the poor in emerging markets will require more than working with the focal elements of exchange (the marketing mix) alone; it will also require working with the contextual, institutional elements that influence exchange. Specifically, firms marketing to the poor will need to be able to carry out the institutional work needed to enable markets to function effectively. This will involve learning how to frame problems and solutions appropriately, working to create the necessary networks, negotiating and influencing regulators and policy makers, and building legitimacy with investors, the media and the public at large.