Abstract

In the light of growing trade and investment flows, the investment relationship between the European Union (EU) and China needs to be revisited. Chinese firms face significant barriers in entering and operating in the European market whilst the European economy needs more investment. Support for investment may be crucial for both the EU and China to improve economic growth. The prospective International Investment Agreement (IIA) seeks to achieve this goal. This paper focuses on Chinese inward foreign direct investment into the EU and on the potential for generating greater mutual EU–China flows, improved market access and investor protection under the IIA.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper focuses on Chinese inward foreign direct investment (FDI) into the European Union and on the potential for progress in generating greater mutual EU–China flows, market access and investor protection under the prospective EU–China International Investment Agreement. An earlier 1985 EC–China Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement yielded the framework for bilateral trade and investment relationsFootnote 1 and, in January 2007, EU–China discussions began with the intention of upgrading and expanding this framework towards a Comprehensive Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA). Parallel to these, EU Member States have individually signed bilateral investment treaties (BITs) primarily to protect investment post entry in China, as well as double taxation treaties (DTTs) for the avoidance of double taxation.Footnote 2 It is true to say that many EU investors would not have dared to invest in China—in particular in the early years—without the protection of a BIT. However, all accept that the world has moved on, and that the relationship needs to be revisited, made coherent, and re-energised.Footnote 3 The EU–China International Investment Agreement (IIA) is precisely the right step in that direction: FDI is the medium through which business relations can best be intensified in the long term, given the vast physical distances between the EU member states and China, as a complement to the already strong EU–China trade relationship.

In addition to the barriers posed to the intensification of trade by physical distance, we have to recognise that Chinese firms face considerable “costs of foreignness” when they seek to establish in the EU. The “cost of foreignness” is a core concept within international business theory and it is something that Chinese firms are believed to face to a degree that is material to their ability to operate within the EU. These costs are not artificially imposed or officially created to discriminate, rather they arise naturally. Chinese enterprises are coming from an emerging economy—an economy that is very different from Europe. And, it can be argued, the Chinese experience encapsulates the sorts of problems that emerging economy investors generally face when arriving in advanced economies. To address this, we need to learn more from the existing arrangements that we have between the Member States of the EU and China, and we need to consider how the European Union’s bargaining power can be improved in order to get the right deal to promote investment relations for both sides.

2 Why FDI and why now?

Following the Treaty of Lisbon,Footnote 4 which entered into force on the 1st December 2009, competence for external investment policy with respect to foreign direct investment (FDI) transferred from Member States to the EU level, and therefore made possible an International Investment Agreement (IIA) between the EU and China. The EU’s enthusiasm for the IIA can be attributed to both EU enterprises’ commercial interests in China and to the growth and employment agenda within Europe.Footnote 5 The focus of the Treaty of Lisbon on FDI is clearly intended to extend the competence of the EU to encompass the entirety of the means used by commercial enterprises to operate and compete internationally. Competition through FDI is the most obvious addition to international trade, to which can be added non equity-based forms of international competition, such as technology licensing, franchising, subcontracting, and so on. The likely reason for the earlier omission of investment from international treaties, including multilateral trade negotiations is that, quite simply, the field of international economics historically poorly theorised anything other than international trade in final goods. Most officials and their advisers charged with designing treaties would easily overlook equity-based competition abroad, regarding FDI rather as private assets located in foreign countries, as if these were simply an indicator of the international standing of the home nation’s wealth. The training that officials would have received, particularly at university, would have looked upon capital flows simply as a balance of payments item, not as a part of the strategic armoury of commercial firms. To an extent, this tendency to lag academic thinking persists to this day. Chaisse has pointed out that EU Member States have historically shown reluctance to cede national control over foreign investment to the EU.Footnote 6 He also notes that “The new Article 207 TFEU includes expressly, and for the first time, ‘foreign direct investment’ under the Common Commercial Policy Title II of the TFEU without, however, providing a definition”.Footnote 7 The excessive precision in identifying, without defining, FDI in the Treaty of Lisbon (see below) almost certainly was precipitated by concern to transform market access for European firms in China. This now risks excluding other forms of investment which are no less important, given the objectives of the EU in wishing to accelerate capital formation across the piece within Europe.Footnote 8

The Treaty of Lisbon specifies the EU’s competence with respect to FDI (only) and, arguably through omission, as inapplicable to portfolio investment.Footnote 9 This might imply that equity investment holdings short of the 10 % threshold, should fall outside the EU’s competence. However, as the 10 % threshold could be argued to be an economic statistician’s convenience with which to infer an effective voice in the management of an enterprise, if such a voice can be proven at shareholdings below 10 %, then the EU’s competence could anyway yet apply.Footnote 10 The IMF manual goes on to specify that “Immediate direct investment relationships arise when a direct investor directly owns equity that entitles it to 10 % or more of the voting power in the direct investment enterprise.” (Id.. p. 101). We can note that in the context of international transactions, the terms "FDI" and "direct investment" can be used interchangeably. We should note that Shan and Zhang (2010) conclude that, in connection with the EU, this widely accepted definition of FDI published by international organization such as IMF, OECD and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) are now reflected in the European Court of Justice’s “Interpretation of the term ‘direct investment’ (used in former Article 57(2) TEC, now Article 64(2) TFEU) in accordance with Directive 88/361/EEC.59. This is given as “Investments of all kinds by natural persons or commercial, industrial or financial undertakings, and which serve to establish or to maintain lasting and direct links between the person providing the capital and the entrepreneur to whom or the undertaking to which the capital is made available in order to carry on an economic activity. This concept must therefore be understood in its widest sense.” As Shan and Zhang (2010) surmise “Although there has been no further clarification on the definition, it is understood that indirect or portfolio. investment, such as short-term loans, contractual claims, and intellectual property rights, is not covered as FDI under the CCP.” It is evident that there is a potential deficiency within the EU’s CCP to negotiate exclusively on the matter of portfolio foreign investment (and any type of investment other than FDI). This may be a gap with which certain Member States might be content, in the competition for inward investment.Clearly this might be an area of contention for the future, particularly as the sums of money invested by sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are considerable and, while theoretically possible, there may arise no element of control in holdings below 10 %.

Shan and Zhang point out that pre-Lisbon the EU did not have exclusive, but rather shared competence with Member States in international investment matters.Footnote 11 In singling out FDI for EU competence (which is a subset of international investment) in the Treaty of Lisbon, the EU would necessarily have to recruit the competence of Member States to conclude a broader IIA covering all forms of investment. Member States’ pre-Lisbon bilateral investment treaties customarily were comprehensive in covering all investment, therefore embracing both FDI and portfolio foreign investment (PFI). So a comprehensive IIA that is, in effect, a super-BIT at the EU level, would need Member States’ agreement to widen the scope of the IIA beyond FDI alone. It would be necessary to include every kind of asset having an economic value—regardless of whether the investor is eligible to exercise an effective voice in the management of the undertaking in which the investment is held. Annacker (2011) notes that ‘Under the common broad definitions of “investment” covering “every kind of asset” owned or controlled by a protected investor, the source of the funds invested and the motivation of the investor in making the investment have been deemed to be irrelevant’.Footnote 12

However, once clarified and agreed, the IIA would bind all Member States, so producing a truly comprehensive common investment policy.Footnote 13

Whether sovereign investors benefit from investment Treaty protection depends on the definitions of “investor” and of “investment”.Footnote 14 As these are yet to be specified within the prospective IIA, and we can only assume that they will be carefully constructed so as to admit capital from whatever source, as the interest of the EU is precisely to encourage all forms of capital.Footnote 15 The fact that Germany amended its legislation in 2009 “Prompted by the concern that investments by sovereign wealth funds could gain political influence in Germany”, warns that, should these concerns persist, or be present in other Member States, then some pressure may arise to limit investment according to the state-related nature of the investor.Footnote 16

The use of the term “market access”, in connection with investment, necessarily implies FDI, rather than any other type of investment, as the “market” referred to references a locus of commercial competition within the host. And with regard to the right of establishment, Annacker notes that few BITs grant investors rights with respect to the acquisition and establishment of investments.Footnote 17 However, it is also fair to say that there are received theoretical motives for FDI that go beyond market access, notably in this connection the motive to compete outside the host state, e.g., through employing lower cost labour with the intention of exporting, or the extraction, or processing of natural resources, or both. Although the low-cost-labour motive is lessening in importance with respect to FDI in China, the growth of the vertical disintegration of production since the 1960s, and the “fine-slicing” of international (or “global”) value chains (GVCs) mean that there is some theoretical imprecision in using the term “market access”.Footnote 18 The right of establishment is more generic in this connection and either should be preferred or used in conjunction with market access.

There are many details that could be addressed in any discussion regarding international investment, such as the extension of national treatment (NT) in ambitious investment agreements,Footnote 19 negative lists of industries, the eligibility of state-related investors, recourse to ICSID, and so on. However, it is not the purpose of this discussion to address these, as we take it for granted that the intention of the IIA is effectively to promote, primarily FDI, but also other forms of beneficial investment. We can only presume that the details will be attended to in the negotiations that are to come. For the same reason, the complex issue of whether EU Member States’ existing BITs should be considered to have been automatically terminated following the Treaty of Lisbon, so creating a void is, again, something with which we will not concern ourselves in this paper.Footnote 20

The fact that EU Member States’ BITs typically did not impose on the host state any compulsion to admit FDI, that is, to extend market access beyond any obligations such as those agreed under the auspices of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) simply means, for the EU–China IIA that for the first time both pre-and post-entry phases will be encompassed within one agreement.Footnote 21

3 The trajectory of EU–China investment

It is very easy to feel deprived of understanding when confronted by data, and this is particularly true of data to do with China as, despite its status as a developing economy, the numbers are always very large indeed. Rather than scale per se, we shall focus on judicious comparisons, on growth rates and, in particular, the flows of FDI, because it is really these that are important for our purpose. In 2012 the growth rate of Chinese FDI to the European Union was 28.6 % year-on-year, and then in 2013, 16.8 % year-on-year. And in 2014, during the first 10 months, the flow had increased by 17.8 % year-on-year. These are the sorts of figures that signify some measure of success for any host economy. But the antidote to these impressive rises is that, currently, the Chinese footprint (the FDI stock) in the European Union is very small, so the increases are in absolute terms, very modest indeed when set again advanced economy investments in the EU. As is often the case with international investment, sometimes it makes sense to look at the stock, while at other times it makes sense to look at the flow. With China it is especially important that we look at the flow. And if we focus on the nature of Chinese investment, we can see that its industrial diversity is growing, which signifies a maturing of Chinese outward FDI, and a stabilisation of the rate of flow that can be expected in the future.

In international negotiations over investment relations between the EU and China there is a basic asymmetry. The EU is very open to inward foreign investment across the majority of economic sectors, so the main scope within the European Union to encourage inward FDI from China lies in investment facilitation and in investment protection. This is effectively what the EU has to offer in exchange for greater market access for EU firms in China. This sort of approach is designed to intervene to counter costs bearing upon firms seeking to transact international business, known as “costs of foreignness”,Footnote 22 costs created by “psychic distance”Footnote 23 and costs arising from a liability of outsidership,Footnote 24 referenced again later. And if Chinese firms invest in the European Union it can, and does on quite a number of occasions, open up export opportunities from the EU into China. That is, actions to reduce costs on one side may have a beneficial effect on investment promotion in both directions. Such greater economic inter-dependence means to say that the EU’s and China’s interests become bound more solidly together.

In Fig. 1 we can see that Chinese global OFDI stock is rising, though it was checked a little by the financial and economic crisis, it is now back on trend, notwithstanding a shift down in the intercept. The bars themselves are less important than the numbers on the vertical axis, which indicate the percentages that Chinese global OFDI stock represents of the world total and that, in 2012–2013, Chinese FDI passed through the 2 % barrier, which is an impressive rate of increase for an emerging economy.

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2015)

Chinese global outward FDI stock.

The financial and economic crisis depressed the growth of EU-27 inward FDI stock coming from China, but as Fig. 2 shows, after 2010 the trend has rebounded with, by 2012, the percentage of inward FDI stock coming from China (indicated on the left hand axis) being well on the way to the 1 % mark. At the time of writing, this 1 % threshold may well have been achieved, but it is perhaps apposite to note that—particularly with EU-level data—it is inevitably only available with a considerable time lag. For data to be consolidated for the entire EU, it requires that statistics from (since the accession of Croatia in 2013) 28 member states should be finalised. It follows that the date at which EU-level figures become available is determined by the most laggardly national statistical office, whichever that might be.

Source: Eurostat (2014a)

EU-27 inward FDI stock coming from China.

4 The scale and scope of investment

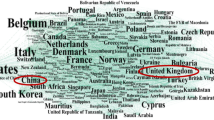

One means of visualising, and putting into perspective, the relative importance of inward FDI into the EU is presented in Fig. 3.

Source: Eurostat (2014b)

FDI Flows to the EU, 2012.

This is an instructive diagram because the arrows-with-national-flags convey plainly that, in terms of FDI flows into the European Union, it is difficult to understand why China is lionised as a front-running potential source country for inward FDI into the EU. At below 1 %—at just 0.68 %—of the total FDI flows into the EU from third countries (in 2012), it is a mystery how precisely Chinese FDI comes to be targeted by the multitude of investment promotion agencies (IPAs) dotted around the Union. The USA alone accounts for 60.81 % of inflows into the EU, that is, two orders of magnitude higher than China. Also ahead are Canada at 3.59 %, the EFTA countries summing to just under 16 %, Japan at 4 %, and Brazil—a fellow “BRIC” economy, reaching 2.49 % in 2012.

Why should the EU be looking to China for FDI when its contribution is so small? The explanation requires an understanding of FDI flows, and of how expectations are formed. One leading proposition is that, in a sense, Chinese investment is characteristically un-hypothecated by location. This means to say it could go anywhere, and the possibility of attracting it is therefore seen as higher, so raising the expected value of investment from targeted investment promotion efforts. Chinese FDI is also seen by EU member state governments and their agencies, as offering the promise of economic regeneration, with capital (however realistic this is) and an entrepreneurial infusion felt to be needed in stalling EU regions. Chinese FDI has almost assumed a mythical status imbued with panacean qualities in the eyes of some inward investment policy makers, but there is a rationale behind this.

It is a fact that much of the investment flows that we observe are reinvested earnings—they are earnings from existing investment in foreign affiliates that are returned for reinvestment into the same companies. It follows that these funds, in effect, stay within the overseas affiliates that generated them, and are held outside the home country of the multinational. These funds are available for reinvestment, though they may not be actually employed for investment until business conditions justify this. But, in principle, there is relatively little competition over where these reinvestment flows (when actually invested in real assets) go: they tend to follow the existing geographical pattern of FDI, by member state and by enterprise. But in the case of Chinese investment, capital flows are far more attractive for targeting, because these are overwhelmingly new capital flows. They are typically not reinvested earnings. Whatever the success, or the financial performance, of Chinese affiliate firms in the European Union, the new capital inflows are more significant. This is simply because the Chinese investment stock is as yet so small, and so new, that even if these investments were to transpire to be highly productive and lucrative, they have not yet had the opportunity to proceed far enough into their business plan to earn substantial income capable of becoming reinvested earnings. So the 0.68 % of Chinese FDI inflow to the EU is small in terms of its importance, but it is large in terms of its significance for the future. It is for this reason that the EU, and many other economies as well, spend so much time studying, and courting, inward investment from China.

While to date the European Union has received a very small share of inward investment from China, now we see the very real possibility of improving upon that, particularly in the context of an international investment agreement. The destination of Chinese outward foreign investment stock, as presented in Fig. 4, suggests good news for the EU—that it appears to be pulling ahead as a host economy. If so, this is timely, as it underlines that the EU–China International Investment Agreement has very real potential to consolidate this trend. Asia, to date the dominant host region for China, is losing share, and, in fact, this explains why all the trend lines that are shown (but not Asia’s) are rising over the period. It can be seen that, of this non-Asia pack of economies, the EU-27 is pulling ahead by 2012, and the EU’s share is moving towards the 7 % mark.

Source: NBS MOFCOM, and SAFE (2013)

Destination of Chinese OFDI Stock, 2003–2012 (€ billion, %).

So far the discussion has not concerned the distribution by industry of Chinese investment into the European Union. This distribution is not the same all around the world (see Table 1).

In the case of manufacturing, the European Union is receiving relatively more than the rest of the world, both in stock and flow terms, while it is taking rather less in terms of wholesale and retail activities. With respect to leasing and business services, however, the EU is a major recipient. It is reasonable to say that, if a significant proportion of Chinese investment is now being directed towards particular sectors, then we need to understand a lot more about these sectors, and to ask whether we expect investment in them to have significant benefits for the European Union. The question of whether Chinese investment in particular is likely to generate the benefits that might be considered normal for these sectors is, then, altogether another matter. The aggregate figures are inadequate to address these questions. If we are to understand what the impact of Chinese investment is, then we really need to drill down to the level of the sector, the industry and, indeed, the activity. To date no such analysis has been completed, though it will yield considerable insights when it is.

For the present, however, there are yet more prominent challenges to our ability to reckon the impact of inward investment from China. The true distribution of Chinese investment is only poorly understood. Figure 5 compares the valuation of Chinese FDI into the EU obtained from using Chinese Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) data (indicated by the white hemispheres) with data from the European Union’s statistical agency, Eurostat (represented by the grey or the black hemispheres, for 2010 and 2011, respectively). It is not so much the absolute amount of the investment that we wish to gauge here, so much as the size of the divergence between the two hemispheres, indicating the respective estimates according to these two different sources—which, ideally, should be yielding the same figures. The discrepancies evident here pervade the data and are severe. At the centre of the distortions are practices arising in member states. In particular Luxembourg is problematic as a “gateway” economy to the European Union, whereby Chinese investment lands in Luxembourg, and is then re-filed as investment elsewhere within the EU.

There is more clarity on the Chinese share of EU-27’s outward FDI stock with still more potential for future growth. In the eight years from 2004 to 2012, the share more than doubled to 2.7 %. If, as part of the process of moving towards the EU–China IIA, an improved grasp of the true statistical picture can be achieved, then it will be not before time.

5 Investment promotion

In the discussion that follows, we draw on two sources in particularFootnote 25 which are studies for the European External Action Service (EEAS) under the Europe-China Research and Advice Network (ECRAN) initiative, led by Kerry Brown, formerly of Chatham House, London, and now of King's College, London. These two studies focused on the phenomenon of Chinese investment in the European Union, and investigated what policy direction the EU should go in, and what effective policy actions might consist of in the future.

Previous studies have supported the idea that the EU should be welcoming Chinese investment: in principle, there are direct benefits, from employment, tax revenues, and indirect advantages to local economies and to growth, all of which are standard in the canon of spillover effects from inward FDI. Given the fact that the EU currently has a small amount of investment from China, relative to the major investors, it is hardly problematic to conclude that the EU should be positive about encouraging Chinese inward FDI. And there is clear agreement on the motives of Chinese investors. They are interested in anything that can help them move up the value chain. Chinese firms want access to markets and to technology, access to skilled labour, and they want to learn how to generate technology and to develop capabilities to improve their competitiveness not just in foreign markets, but in their home economy as well. All of these motives for internationalising are perfectly reasonable and well known within the theory of international investment. The one noteworthy feature—which policy makers should bear in mind—is that China today arguably has more firms in the condition of needing these sorts of development opportunities than any other economy, and perhaps more than any other economy has in the past.

The question of how to attract investment is well studied. The European Union member states employ, broadly speaking, two alternative, approaches. First, there is one we designate as the ‘Broad Approach’ whereby EU member states’ embassy and consular staff widely promote the general investment opportunities available in their home economies—for example, via trade fairs and, at the same time, profiling their home economies in government-to-government discussions. Second, there is the ‘Deep Approach’ to encouraging inward investment, through the investment promotion agencies (IPAs)—the trade and investment promotion arms of member states’ governments, and local governments. These agencies, and their branches located within China, target and contact businesses directly, and can offer matchmaking services. They are supported by dedicated promotion staff at embassies and consulates—giving potential Chinese investors a strong feeling of being genuinely and sincerely wanted. In view of the fact that the way of doing business, certainly in Asia, is very much more personalised than in the West, this approach is often felt to be more effective. Reaching out to potential investors in terms that the investor recognises and would understand best, is likely to achieve a better result for both sides, and a meeting of the minds about the projects in question.

Pre-establishment of FDI, Chinese firms do lack knowledge and understanding about the local market. This deters investment as, wherever there is inadequate information and knowledge, this risks negative investment experiences. The EU regulatory environment for Chinese investors can be a minefield because, notwithstanding the achievements of the Single Market, the Union is, in fact, quite bewildering, particularly for smaller firms. A leading contributor to this is that there are many business relevant factors that differ between member states, on a state-by- state basis. Chinese firms typically lack skills relevant to internationalisation, and their capabilities to organise themselves internationally may be weak. It is important to remember that these are firms that have only recently internationalised. They have not had decade upon decade of experience of operating at scale. And they have not had the long track record of operational experience that many western firms have had before they took the first steps to internationalise. Naturally, this lack of experience can affect business performance.

Investment promotion agencies aim to work closely with potential investors to help them, but gaps in Chinese firms’ understanding, and in their capabilities, inevitably persist. Invest in Sweden, the Swedish investment promotion agency reported that it observed Chinese first-comers into the Swedish domestic market characteristically to be small entrepreneurial firms, subsequently followed by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), with the large private firms entering last.Footnote 26 Observations made by UK Trade and Investment (UKTI) were that Chinese firms follow the incremental increases in foreign market commitment that are a well-known feature of pioneering foreign investors—actually known as the Uppsala model of firm internationalisation—though, in this case seen for Chinese firms in the UK rather than Swedish firms venturing abroad, as in the original study by Johanson and Vahlne.Footnote 27

Investment promotion agencies recognise many different types of investment behaviour and preferences, which underscore the importance of having a good understanding of the customer. And, there are many different types of investors, while the European Union itself has a range of needs, including the improvement of its technology base. But generally speaking, no policy maker is expecting Chinese firms to come to the European Union en masse to bring technology with them. Rather, EU member states are hoping that Chinese firms be substantially based in the EU, and from this base to compete internationally. The desire is that they bring resources with which to stimulate the competitive environment, including investment in R&D-intensive activities, and thereby foster an environment in which the EU realises its full potential to generate technology. In short, Chinese firms are looked to, not to bring technology, but to create it.

There are three broad categories of governance of Chinese investors: privately owned, state-owned and sovereign wealth funds. Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are something of an anomaly, or even an enigma, in foreign investment terms: they are not really foreign direct investors in the received sense. They are not, unlike privately owned and even state-owned firms, commercial enterprises. They are impartial towards foreign investment in the form of FDI or portfolio foreign investment (PFI) in a commercial business sense per se.Footnote 28 They primarily seek solid returns. On occasion, they might appear to behave as foreign direct investors, but their equity ownership typically falls short of the 10 % threshold necessary to infer the existence of a foreign direct investment in economic-statistical terms. Their lack of motive to secure equity-based control is explained by this disinterest in strategic management. But it is compensated for by their determination to invest in firms which already have management in place in which they can have confidence, in particular to generate (ideally) predictable revenue streams, year after year. This is because SWFs are the custodians of a nation’s financial wealth. All sovereign states have such funds, and it is normal for individual states to have a number of funds. China happens to have some of the largest and fastest growing funds and, owing to these funds’ need to diversify away from a reliance on gilt-edged securities issued by foreign governments, the demand for portfolio investment in equities has been rising, seemingly inexorably.

It is essential to understand the different motives between these types of investors, if we are to be able to anticipate how they might respond to changes in policy towards international investment, in particular, as part of an International Investment Agreement. Private firms tend to want to improve their existing competitive capability, to gain technology, and some seek capital that cannot be secured at home. State owned firms, on the other hand, have subsidised access to capital and, at least historically, have enjoyed soft budget constraints through their close relationship with the state (at one or more levels). State owned enterprises are motivated to learn how to compete effectively in markets abroad, as reform of the state owned sector at home necessarily means that they have to become far more like privately owned enterprises in terms of performance. Exemplars for many SOEs are firms such as Huawei. The success of Huawei, the major telecommunications equipment manufacturer and supplier, is iconized at home. Its combination of technological innovation built around anticipating the buyer’s needs, and low-cost manufacturing (in China) means that its value proposition to client enterprises and many governments is hard to beat.

These different types of investors have different needs when it comes to investment abroad, and in particular with respect to investment in the EU. But the difference in governance between them may also have implications for post- establishment behaviour, as well as performance. State-owned enterprises, through their close relationship with the Chinese government in the home economy, are generally thought to enjoy preferential access to capital for investment. And this may well extend into the international sphere, somewhat de-linking investment performance from the availability and cost of capital to the firm—perhaps especially if the industry concerned is one of indentified importance to the Chinese government. There is good reason to expect more “churn” in investment for the smaller, more numerous privately-owned firms. The barriers to exit are likely to be lower for privately owned firms, some of which have had very mixed success. Some have withdrawn and had to liquidate investments. Scientifically, not enough is known about the difference in behaviour according to governance by ownership type. There has not yet been a long enough run of data to establish reliable relationships, and to arrive at conclusions. But we should expect that smaller privately owned firms will likely have to pay their way relatively quickly within the European market, and so their contribution to investment in the EU may be more volatile.

6 The prospects under the International Investment Agreement

What are the opportunities for the future? For certain the patchwork of EU member states’ bilateral investment treaties (BITs) has been in need of an overhaul even before the Lisbon Treaty. Existing BITs had already been recognised as ineffective with regard to the promotion of inward FDI into EU members.Footnote 29 The treaties of the twenty-six member states with BITs—at the time of the Lisbon Treaty the Republic of Ireland was the exception—focused on protection in China rather than on bringing Chinese FDI into the EU. It follows that, for the future, the EU needs robust market access for EU firms in China and, in return, the EU needs to be able to afford comprehensive investment protection—and protection of the right to invest right across the EU—to Chinese investors. Chinese firms fear non-transparent national barriers, often linked to security concerns that transpire only at the time of the proposed investment. There might appear to be no barriers ex ante but, when an intention to invest is declared, a barrier might arise from some quarters—most commonly in response to the wish to make an acquisition. Such pressures are not uncommon at the member state level, much less so at the European level. The good news is that all of the parties—governments and firms—view the reform agenda in China as congruent, so improving the prospects for negotiating a mutually beneficial International Investment Agreement. It follows that the effect of an EU–China IIA will necessarily involve binding the hands of Member States in times of latent public controversy.

As of 2015, the EU China IIA negotiation process is nascent. So far “talks have been about talks”—the third round of discussions was held in June 2014, with the main negotiations yet to come at the time of writing. The EU negotiators will need a clear view of the current position of investment relations, and the barriers to investment, across a range of key sectors in both China and the EU. They will need to have a command of the way in which the existing barriers have shaped current international investment positions and, therefore, what the potential is for mutual gain. The EU must surely aim to replace the existing legacy external investment regime by a comprehensive IIA that exploits the EU’s collective bargaining power. China does not have any similar gains available to it, as it is already a unitary bargaining entity. However, China does have regional and local development ambitions and, given that China’s economic rise largely utilized a large and sustained inward inflow of FDI under the Open Door Policy, it would be logical for discussions with the EU to pay attention to China’s regional dimension, and how the EU can contribute to realizing these. Such are the likely starting positions, but the methodology for the EU to reach these theoretical gains is likely to be the application of the elements of best practice drawn from member states’ existing bilateral investment treaties. In principle, the use of the most ambitious BITs as a template for the IIA will mean that the EU will then be shifted into a better position to offer greater benefits for Chinese investors.Footnote 30 The bilateral nature of the prospective IIA means that a benefit extended to the other party demands a justification in terms of benefit received in exchange.

Member states with the least ambitious BITs would therefore, at the minimum, secure improved terms. At the one extreme is the Republic of Ireland, having no bilateral investment treaty—for the very logical reason that those EU members’ with BITS were pursuing protection in China. Irish governments had judged that, as Ireland did not—until relatively recently—have significant outward investment and, given that bilateral investment treaties are costly to negotiate, it did not, at the time, merit the effort. It is clear, that there should be substantial economies of collective action in external investment relations. And it is then no surprise that the EU is moving into a very active phase of international trade and investment treaty negotiation.

So far our discussion has focused on the rationale for the EU to pursue the IIA. For the Chinese government, the strength of its desire for Chinese firms to invest abroad—and the desire of Chinese firms themselves—is the main bargaining chip for the EU. Private sector, and especially smaller, Chinese investors are now very much more outward looking, not least for the reason that they face intense competition in their home economies. And, while Chinese firms might bring enterprise and investment in R&D, they nevertheless may need mentoring. The smaller Chinese firms do not typically bring substantial amounts of capital, but they characteristically do bring enterprise, which is a quality needed in the European economy. The Chinese government feels its firms are often poorly informed, and lack capabilities in terms of FDI. Very often that is the case, exacerbated by the anecdotal evidence that Chinese firms, perhaps especially the smaller investors, begrudge the payment of fees for market intelligence and due diligence in the prospective host market. It follows that Chinese enterprises could be assisted by the establishment of chambers of commerce, the development of improved investment facilitation, and the training of Chinese firms in how to do business in the EU.

The International Investment Agreement in prospect would cover investment only. But this agreement could serve as an element in a later, and broader, free trade agreement. An international bilateral investment agreement would help to create a framework for supporting Chinese FDI into, and around which, other initiatives could nest. And there may well be some coordination with the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), for example, the provisions for the one agreement may well be re-used, in some way, in the other.

The International Investment Agreement between the EU and China not only needs to be informed by member states’ existing BITs, particularly those that are the most effective, it also needs to draw on investment promotion agencies’ best practice. However, each of the member states will have somewhat distinct interests when it comes to investment in China, in terms of industries and sectors. But, with regard to investment into the EU, the interests of each member state are far more congruent. The problem is that post-, as pre-, IIA, there will remain natural competition between member states to attract investment. The demand upon the EU is to find a single voice, otherwise member states will continue to undercut each other, in a competitive chase after inward FDI. Such internal competition is not so much a problem for China, though competition does exist. Large and experienced EU firms are generally well informed enough to identify the best locations in which for them to invest. But this is less true of smaller, and more naïve, Chinese investors.

7 The impact of an EU–China IIA

Shan underscores an important point that is often lost in the analysis of legal provisions—that of impact upon investor behaviour. Referring to FDI into China, the author concludes that the purposeful establishment of a favourable legal system towards inward FDI has made a considerable contribution to China’s success in attracting foreign firms to locate locally.Footnote 31 By extension, the law has then had a fundamental impact on China’s achievements in terms of economic growth, as the Chinese growth and development strategy has been built upon inward FDI bringing capital, technology, know how, management and marketing skills, and so on, under the Open Door Policy. Shan also makes another pertinent point, unrelated to the provisions in the law itself. His earlier surveyFootnote 32 identifies the two-stage behavioural nature of decision making in investor behavioural responses to policy, and is worth quoting in full:

“The author’s survey has shown that although most EU investors tried to investigate the governing national and international laws before they invested in China, less than 50 % of them knew that there were bilateral investment treaties to be taken advantage of, and the knowledge of MIGA Convention and ICSID ConventionFootnote 33 was much worse (less than 20 %). Unsurprisingly, such a lack of legal knowledge has prevented EU investors from taking full advantage of the market opportunities provided by China.”Footnote 34

Clearly, if investors are unaware of the availability of support, then they cannot make investment decisions in the light of it. The critical point here is that the issue of awareness is certainly no less important for Chinese investment in the EU. Arguably, it is a matter of paramount importance, as potential Chinese investors, and existing Chinese investors, are comparatively naïve compared with EU enterprises, having only been exposed to international competition for a remarkably short space of time.

The implication is that there is clearly great scope for policy impact, not only via the quality of legal provisions but also via their effective promulgation and the targeting of potential investors—on both sides. This would have to be bound into the EU–China IIA from the outset for the Agreement to be effective. What is more, as China is a developing economy, it has extensively employed differential industrial policies and non-uniform trade administration instrumentally by location. This has created an internal patchwork that is a matter of concern for WTO members.Footnote 35 This internal heterogeneity might be seen as offering opportunities for foreign investors into China, but at the same time creating a potentially bewildering environment that might heighten the problem of ensuring awareness and certainty in potential investors. At the same time, it follows symmetrically that Chinese investors from different parts of China can vary dramatically in their readiness, capability and preparedness to invest in the EU.

8 Conclusion

Promotion is, as noted above, especially important for inward investment into the EU, both in terms of quantity, and quality, as those EU member states with REIO exception clausesFootnote 36 have, in practice, not invoked them. There is little incentive to bar inward investment in a world in which capital is highly sought after—a situation that has obtained since the 1990s, spurred by widespread market liberalisations during the 1980s, and the competition for investment created by this. For the negotiators, the link between investment promotion and investor behaviour, investment performance and, ultimately, impact must be top of the agenda. Understanding impact means dispensing with the assumption that “more investment is better” and asking “what is the benefit?”. Scientifically we do not know enough as yet. For this reason we need better quality statistics—data on FDI and on barriers, but particularly research on the effect of barriers. Negotiators, and those preparing analyses, need robust operational data if sound policy advice, and evaluation, is to be achievable. Ultimately, we need to be able to gauge investment impact. There is a wealth of anecdotal evidence that Chinese firms face significant barriers in entering and operating in the European market. These are summed up in theoretical terms, such as the “costs of foreignness” and the more all-embracing “costs of outsidership”. In what is now the fairly dim and distant past, these excess costs bearing upon foreign enterprises were perhaps seen by governments as a competitive advantage to incumbent domestic firms. But when, as now, the European economy is in need of attracting investment, it behoves the EU to attack these costs of outsidership, through improving investment facilitation and the ease with which Chinese firms can navigate through, and across, member states that are as diverse in character as any advanced economies can be.

At present we know too little about what the impact of legal changes will be upon behaviour or uptake of the changed policy environment. But we can be sure that awareness of the availability of these changes will be a crucial factor in determining the ultimate benefit. There are likely to be challenges of ensuring wide awareness of the availability of support for investment and of investment opportunities, for both the EU and for China. However, the IIA is not only likely to yield significant and important benefits to mutual legal provisions, but also to raise awareness of the availability of opportunities. These two outcomes are jointly critical to the impact that the IIA will exert on mutual FDI flows, so enabling the two economies of the EU and of China, and their enterprises, to better exploit and develop economic growth within each other’s space.Footnote 37

It is truly now a two-way street between the EU and China. In the light of the intentions of the EU and China in seeking the IIA, we should have confidence that the current lack of certainty can be settled once and for all, in the light of rigorous analysis of the respective current investment positions and the opportunities, that exist.Footnote 38

Notes

Replacing the 1978 Trade Agreement (Shan 2002).

Both have the effect of promoting mutual investment, but only through intensifying investment in those industries and sectors in which establishment is permitted to foreign entities. That is, BITs customarily do not address pre-entry conditions. The effect of EU Member States’ BITs is presumed to be greater for EU investment in China than vice versa, as the standard of protection has been the bigger issue for EU outbound investment.

Shan (2002) notes that “Bilateral legal instruments are playing a more important and substantial role in current EU-China investment relations, when contrasted with the role played by multilateral legal instruments.” And that “This is confirmed by the Author's (2001) Survey, which shows that EU investors tend to pay much more attention [to] bilateral agreements than multilateral agreements.” (Id.. p. 610). This has direct implications for the impact of the IIA on the awareness of potential investors, and existing investors, and so on their investment decision making.

Officially, the Treaty amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community, [2007] OJ C 306/1. Following Chaisse (2012) we employ the new numbering of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Gstöhl and Hanf (2014).

Chaisse (2012).

Id. p. 57. Before the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon, the EU had shared—but not exclusive—competence in international investment matters, as none of the treaty provisions, from the foundation of the EU, covered international investment. Lisbon was the first treaty to include international investment, in the form of exclusive competence for FDI at the EU level (Miron 2014).

Shan and Zhang (2010) record that “While it is clear that FDI is included in the CCP (Common Commercial Policy), there is no definition of the term ‘foreign direct investment’, nor is there any clarification of the exact scope of FDI under the CCP.” The authors then point out that “Article 206 TFEU [Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union] sets out the objectives of the CCP [Common Commercial Policy]” and, in doing so, “It follows the former Article 131 TEC [Treaty establishing the European Community] but adds ‘foreign direct investment’ in parallel to ‘international trade’ as the areas in which the Union intends progressively to prohibit restrictions.” They argue that “This parallel phrasing has implications in the interpretation of Article 207 TFEU particularly with regard to the question whether the FDI mentioned in Article 207(1) TFEU should be interpreted to cover the entire area of FDI or only ‘trade-related aspects’ of FDI’” (Id.. p. 1058). Again, this will need to be specifically addressed in the IIA.

Chaisse (2012), p. 57. Though opinion varies as, the EU Treaty, already before Lisbon, prohibits restrictions on capital movements, including those relating to third countries, and so would cover portfolio investment.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF 2013), following the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD 2008), defines FDI thus: “Direct investment is a category of cross-border investment associated with a resident in one economy having control or a significant degree of influence on the management of an enterprise that is resident in another economy.” (IMF 2013, p. 100).

Shan and Zhang (2010).

Id., 2011, p. 562. Shan (2002) draws on the 1982 Sino-Sweden BIT as representative, which determines investment to include, as is common with BITs, “Every kind of asset”:

-

Movable and immovable property as well as any other rights in rem, such as mortgage, lien, pledge, usufruct and similar rights;

-

Shares (or bonds) or other kinds of interest in companies;

-

Title to money or any performance having an economic value; Intellectual property rights such as copyright, industrial property rights, technical processes, trade-names and goodwill; and

-

Such business-concessions under public law or under contract, including concessions regarding the prospecting for, or the extraction or winning of natural resources, as given to their holder a legal position of some duration. (Id.., p. 605).

-

It is interesting that definitions of investment in treaty making may be excessively precise, or absent altogether. For example, as Shan (2002) notes, under the ICSID regime while a dispute must “arise directly out of an investment” the Convention does not define investment (Id.., p. 570).

Annacker (2011).

The definition of “investor” within BITs is not as comprehensive and universal as is the definition of “investment”, Shan (2002) points out that regarding natural persons most BITs use "nationality" as the defining criterion while, others use "residence" as the only or additional criterion. And for ‘juridical persons, partnership, or economic organisations … most BITs defines "investors" as those incorporated or established in accordance with the law of a contracting party and having their seat (residence, domicile, headquarter or registered head office) therein’ (Id.. p. 605). The IIA will need to address this definition, given the ease with which the seat of an ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) of an investment may change following international acquisition or merger. However, the seat of the proximate beneficial owner (PBO) may remain unchanged (i.e., within the EU or China) thereby simplifying the matter.

Annacker (2011), p. 545.

Annacker (2011). And note in particular the distinction between market access and the right of establishment. Market access is a General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) concept and prohibits quantitative restrictions. The right of establishment concerns non-discriminatory admission.

See UNCTAD (2003, Table III.1, p. 85) for the broad range of host country determinants of FDI.

That is, beyond most-favoured-nation (MFN) treatment, the EU and China both now being members of WTO.

See Miron (2014).

The WTO Agreement contains a further set of more recent agreements relevant to FDI, and therefore the IIA will concern issues in connection with these. They include the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (the TRIMs Agreement) regulating investment in conjunction with multilateral agreements on trade in goods (i.e., market access). The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) is relevant to investment as it is now recognised that services’ trade is often only feasible through the establishment of FDI, and so market access and national treatment of investment in service sectors can equate with trade access. The Agreement on Trade-related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs), the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCMs), the Dispute Settlement Understanding (DSU) and the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM) are all regarded as having continuous and direct relevance to FDI (Shan 2002, p. 590). Shan suggests that “Most of the WTO agreements and their implementation measures are related to FDI since they influence the FDI environment in its entirety” (Id., p. 590).

Hymer (1960, 1976).

Johanson and Vahlne (1977).

Johanson and Vahlne (2009).

Clegg and Voss (2012).

Johanson and Vahlne (1977).

Portfolio foreign investment does not reach the 10 % threshold of equity holding normally used by economic statisticians to infer the existence of a desire to have an effective voice in the management of an enterprise (that is, the enterprise in which the equity stake is held). It is therefore mutually exclusive with FDI.

The shortcomings of the 1985 EC-China Trade and Economic Cooperation Agreement and the tissue of Member States’ BITs are collectively insufficient to protect mutual investment and, in particular, fail to promote the extension of the right of establishment (“market access”) (see Shan 2002, pp. 610–611). As the EU is a regional economic integration organisation (REIO), incompatibilities and conflicts with Member States’ provisions are readily generated, and a harmonisation process is required (Radu 2008). The reader interested in the legal complexities, inconsistencies, conflicts, actual and potential, that attach to investment (variously defined or undefined) in the context of the EU and its Member States is advised to consult Karl (2004).

Customarily BITs have been North–South agreements, to bolster legal protection of investments in developing economies. Radu (2008) notes that the core rights granted to foreign investors include non-discrimination, fair and equitable treatment (FET), protection against expropriation, free transfer of funds and access to international dispute settlement mechanisms (Id.., p. 239).

Shan (2002).

Referenced in Shan (2002).

The Convention Establishing the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (the MIGA Convention, entering into force in 1988) and the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States (the ICSID Convention, 1966) are two familial World Bank Group multilateral agreements devoted to specific aspects of international investment. As also indicated by Shan (2002). The Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation (the WTO Agreement, 1995, joined by the EU and all Member States from the outset) is closely related to investment issues and, collectively, such bilateral and multilateral agreements constitute the international legal framework for investment between the EU and China. The conventions do not concern themselves with “market access” (pre-entry) rather with the protection of investment and dispute settlement (post-entry). While WTO accession does circumscribe the obligations of signatories pre-entry by industry and sector (as it did for China, which joined on 11 December 2001) it is left for future multilateral negotiations to amend these, or to agreements such as the IIA.

Shan (2002), p. 557.

Shan (2002) refers to differential administrative levels, and special economic areas (SEAs), consisting of Special Economic Zones (EZs), border trade regions (BTRs), minority autonomous areas (MAAs), open coastal cities (OCCs), economic and technical development zones (ETDZs) and “other areas where special regimes for tariff, taxes and regulations are established” (Id.. pp. 592–593).

Clauses generically to limit third country free riding on the advantages (pre- or post-establishment) resulting from REIO membership of the partner country.

As Karl (2004) rightly points out, the EU and its Member States have jointly concluded IIAs with third countries that include innovative features. These encompass the facilitation of administrative procedures for FDI, access to capital markets, the provision of information about investment opportunities and the pursuit of deregulation. Given the importance of widespread awareness of the availability of provisions, innovations such as these offer considerable scope within the IIA for the stimulation of mutual investment.

We should note that the World Investment Report (UNCTAD 2003) singled out the lack of predictability of host economy regulatory environments as a leading brake on FDI flows. For the IIA to achieve success, some have argued that the EU will require effective “Comprehensive FDI Competence” i.e. “Regarding admission, capital movement (transfer), post-admission treatment including FET [fair and equitable treatment], performance requirements and free movement of key personnel, expropriation, and investor–state dispute settlement. This effectively covers all major aspects covered by a typical BIT” (Shan and Zhang 2010, p. 1064) with a rider to also include competence for other investment types, notably portfolio investment by agreement with all Member States.

References

Annacker C (2011) Protection and admission of sovereign investment under investment treaties. Chin J Int Law 10(3):531–564

Chaisse J (2012) Promises and Pitfalls of the European Union Policy on Foreign Investment—How will the New EU Competence on FDI affect the Emerging Global Regime? J Int Econ Law 15(1):51–84

Clegg J, Voss H (2012) Chinese overseas direct investment into the European Union long briefing paper for the Europe-China Research and Advice Network (ECRAN) of the European Commission

Clegg J, Voss H (2014) Chinese overseas direct investment into the European Union in China and the EU in context. In: Brown K (ed), Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Eurostat (2014a) Foreign control of enterprises—breakdown by controlling countries. European Commission, Luxembourg

Eurostat (2014b) EU direct investment flows, breakdown by partner country and economic activity [bop_fdi_flows]. European Commission, Luxembourg

Gstöhl S, Hanf D (2014) The EU’s Post-Lisbon free trade agreements: commercial interests in a changing constitutional context. Eur Law J 20(6):733–748

Johanson J, Vahlne JE (1977) Internationalization process of firm—model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J Int Bus Stud 8(1):23–32

Johanson J, Vahlne JE (2009) The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: from liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J Int Bus Stud 40(9):1411–1431

Karl J (2004) The competence for foreign direct investment: new powers for the European union? J World Invest Trade 5(3):413–444

Miron S (2014) The last bite of the BITs—Supremacy of EU law versus investment treaty arbitration. Eur Law J 20(3):332–345

NBS, MOFCOM, and SAFE (2010) Statistical bulletin of China’s outward foreign direct investment (English version) [data of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS), Chinese Ministry of Commerce of China (MOFCOM) and State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)]. MOFCOM. http://hzs.mofcom.gov.cn/. Accessed 13 Mar 2016

NBS, MOFCOM, and SAFE (2011) Statistical bulletin of China’s outward foreign direct investment (English version) [data of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS), Chinese Ministry of Commerce of China (MOFCOM) and State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)]. MOFCOM. http://hzs.mofcom.gov.cn/. Accessed 13 Mar 2016

NBS, MOFCOM, and SAFE (2013) Statistical bulletin of China’s outward foreign direct investment (English version) [data of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS), Chinese Ministry of Commerce of China (MOFCOM) and State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE)]. MOFCOM. http://hzs.mofcom.gov.cn/. Accessed 13 Mar 2016

Radu A (2008) Foreign investors in the EU: which ‘Best Treatment’? Interact Bilater Invest Treaties EU Law Eur Law J 14(2):237–260

Shan W (2002) The international law of EU investment in China. Chin J Int Law 1(2):555–614

Shan W, Zhang S (2010) The treaty of Lisbon: half way toward a common investment policy. Eur J Int Law 21(4):1049–1073

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2003) World Investment Report 2003, FDI Policies for Development: National and International Perspective, New York and Geneva: United Nations

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2015) UNCTADstat [UNCTAD online database], New York and Geneva: United Nations. UNCTADstat. http://unctadstat.unctad.org/. Accessed 13 Mar 2016

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Joachim Karl, Chief of the Policy Research Section in UNCTAD, Division on Investment and Enterprise, Geneva, Switzerland, for his comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Clegg, J., Voss, H. The new two-way street of Chinese direct investment in the European Union. China-EU Law J 5, 79–100 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12689-016-0063-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12689-016-0063-x