Abstract

The risk of bleeding complications during regional anesthesia procedures is a significant patient safety consideration. Nevertheless, existing literature provides limited guidance on the stratification of bleeding risk for peripheral nerve and newly described interfascial plane blocks. Our objective was to produce an evidence-based consensus advisory that classifies bleeding risks in patients undergoing regional peripheral nerve and interfascial plane block procedures. This advisory is intended to facilitate clinical decision-making in conjunction with national or local guidelines and to guide consideration for appropriate alterations to anticoagulation regimens before specific regional anesthesia procedures. In pursuit of this goal, the Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Section of the Canadian Anesthesiologists Society (CAS) assembled a panel of seven Canadian experts to classify the risk of bleeding complications associated with regional peripheral nerve and interfascial plane blocks. At the 75th annual meeting of the CAS in June 2018, the panel’s expert opinion was finalized and the published literature was quantified within an organized framework. All common peripheral nerve and interfascial plane blocks were categorized into “low risk”, “intermediate risk”, and “high risk” based on the literature evidence, bleeding risk scores, and consensus opinion (in that order of priority). Clinical data is often limited, so readers of this consensus report should be reminded that these recommendations are mostly based on expert consensus. Hence, this advisory should not to be defined as a standard of care but rather serve as a resource for clinicians assessing the risk and benefits of regional anesthesia in management of their patients.

Résumé

Le risque de complications de saignements pendant les interventions sous anesthésie régionale constitue un enjeu important en matière de sécurité des patients. Cependant, la littérature publiée à ce jour ne fournit que peu de recommandations concernant la stratification du risque de saignement en cas de blocs des nerfs périphériques et des blocs du plan interfascial, une technique récemment décrite. Notre objectif était de créer des recommandations consensuelles fondées sur des données probantes qui stratifieraient le risque de saignements chez les patients subissant des interventions de blocs de nerfs périphériques et du plan interfascial. Ces recommandations ont pour but de faciliter la prise de décision clinique en conjonction avec les directives nationales ou locales et d’orienter la réflexion quant à des modifications adaptées à apporter à l’anticoagulation avant certaines interventions d’anesthésie régionale spécifiques. Pour ce faire, la Section d’anesthésie régionale et de douleur aiguë de la Société canadienne des anesthésiologistes (SCA) a rassemblé un panel de sept experts canadiens afin de stratifier le risque de complications de saignement associées aux blocs des nerfs périphériques et du plan interfascial. Lors du 75e Congrès annuel de la SCA en juin 2018, l’opinion du panel d’experts a été finalisée et la littérature publiée a été quantifiée dans un cadre structuré. Tous les blocs usuels des nerfs périphériques et du plan interfascial ont été classifiés en « risque faible », « risque intermédiaire » et « risque élevé » selon les données probantes de la littérature, les scores de risque de saignement et l’opinion consensuelle (dans cet ordre de priorité). Les données cliniques sont souvent limitées, c’est pourquoi les lecteurs de ce rapport consensuel doivent garder à l’esprit que ces recommandations sont principalement fondées sur le consensus d’experts. Par conséquent, ces recommandations ne doivent pas servir à définir une norme de soins; plutôt, elles devraient constituer une ressource pour les cliniciens évaluant les risques et bienfaits d’une anesthésie régionale dans la prise en charge de leurs patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Bleeding complications following peripheral regional anesthesia procedures are fortunately quite rare, but when they occur, they can result in significant patient morbidity. The risk of such bleeding complications following regional anesthesia procedures has been the subject of numerous articles and guidelines.1,2 Recent recommendations classify common regional or pain procedures according to the potential risk of serious bleeding3 and several excellent reviews1,2,3 describe appropriate alterations to anticoagulation regimens based on the risk of the regional anesthesia procedure.

While the most recent American Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines on regional anesthesia in the setting of anticoagulation or thrombolytic therapy acknowledge that the clinical consequences of bleeding following a regional anesthesia procedure differ depending on the location, body habitus, site compressibility, associated comorbidities, or anticoagulation status,1,2 it falls short of risk stratification for individual blocks. Nevertheless, without a clear classification of bleeding risk for specific peripheral nerve or interfascial plane procedures,1,2,3 current clinical decisions mostly depend on the individual clinician’s ad hoc opinion. Understanding the individual procedural bleeding risk may facilitate improved clinical decision-making.

An evidence-based or consensus-based risk assessment of peripheral nerve and interfascial plane blocks is needed. The goal of this advisory is therefore to define the risk of bleeding complications associated with common peripheral regional anesthesia procedures. We present the evidence basis for these recommendations and when insufficient evidence exists, the rationale for stratification based on risk scoring or expert consensus. This advisory is intended to complement existing regional anesthesia guidelines on the management of coagulation. In this way, clinicians can better apply their respective national or local guidelines with appropriate alterations to anticoagulation regimens based on the associated bleeding risk of the specific regional anesthesia procedure.

Panel creation and consensus process

Scope

This advisory focuses specifically on the risk of bleeding and its sequelae following peripheral nerve blocks, truncal blocks (such as paravertebral block or intercostal blocks), and interfascial plane blocks. The population considered includes both adult and pediatric patients. The advisory does not address bleeding complications following neuraxial regional anesthesia procedures (such as spinal or epidural anesthesia), facet joint/median branch blocks, or epidural steroid injection. It similarly does not address the risk of non-bleeding complications such as infection or non-bleeding-related neurologic injury related to these procedures. To provide context for the reported bleeding complications, we noted whether or not these occurred in the setting of an altered coagulation status. Nevertheless, the scope of the advisory includes all bleeding complications irrespective of patient’s coagulation status.

Panel composition

In April 2018, the Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Section of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society (CAS) convened a panel of seven recognized Canadian experts in regional anesthesia and acute pain medicine to review the evidence and classify the risk of bleeding complications following peripheral regional nerve blocks. The panel was chaired by one of the authors (B.C.H.T.) and the remaining panelists included the chair, vice-chair, two other executive and two general members of the CAS’ Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Section (2017-2018).

Definition of bleeding complications

For the purpose of this advisory, bleeding complications were defined as the occurrence of vascular puncture, active bleeding, or hematoma formation attributable to a peripheral nerve or interfascial plane block. Any such complications that at least necessitated further observation for outcomes such as hemodynamic instability or organ damage, were considered for this report. Reports were also included if trauma subsequent to the block procedure needed additional investigations or interventions to diagnose or treat such complications. Given the rarity of adverse events such as bleeding complications, these may be under-represented in both randomized and non-randomized studies. We therefore considered bleeding complications as attributable to the nerve blocks irrespective of the individual level of supporting evidence.

Literature review and consensus methodology

A first meeting of the panelists was convened at the World Congress on Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (New York, April 2018) to discuss the creation of a potential consensus document and to allocate individual panelists to perform the systematic literature reviews for specific anatomic regions including head and neck blocks, upper limb blocks, lower limb blocks, interfascial plane blocks, or paravertebral and intercostal blocks. Each panelist performed the literature search using the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases in May 2018 (see “Literature and search strategy” section).

The panel agreed to the following process for creating the procedure-specific recommendations:

-

1.

Prior to performing the in-depth literature review, each panelist provided their expert opinion of the bleeding risks for each of the common peripheral nerve and interfascial plane blocks.

-

2.

Panelists then participated in a survey assigning a score to each peripheral nerve and interfascial plane block according to a newly proposed bleeding risk Critical, Intervention, and Assessment (CIA) scoring system4 (Table 1) as a starting point of discussion and consensus formation. This CIA system is organized around three parameters: 1) whether the block is performed in proximity to a critical structure; 2) whether a bleeding complication would potentially require invasive intervention; and 3) whether it would be difficult to assess the severity of the bleeding complication. A score of 0 or 1 was assigned to each parameter depending on whether it was absent or present, with the total score ranging from 0 to 3. From the total score, the associated risk can be categorized as low risk (CIA = 0), intermediate risk (CIA = 1), or high risk (CIA = 2 or 3). The results of panelist CIA scores are summarized in the Appendix.

Table 1 Bleeding risk score system4 -

3.

A level of priority was established to give priority to literature evidence over the CIA score results, which in turn was given priority over consensus-based opinion.

-

4.

When a bleeding complication was attributable to a nerve block, the subsequent sequelae were considered in grading the risk.

-

5.

The consensus opinion and CIA risk scores were used if published evidence for a particular nerve block/interfascial plane block was absent.

-

6.

When a difference occurred between the CIA score and consensus opinion, the final risk assignment was based on overall agreement among all the panelists. In addition, the rationale for the consensus was recorded and described for each block in their corresponding sections.

A second meeting of the panelists was held at the 75th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society in Montreal, Canada (June 2018). The above process was applied at this session resulting in the consensus statement for each peripheral nerve and interfascial plane block.

Quality of evidence and grades of recommendation

The quality of evidence obtained from the literature searches was assessed by the panel. The final risk recommendations were subsequently graded using the previously described Statements of Evidence and Grades of Recommendation (Table 2).5

Literature search strategy

The literature search was conducted in May 2018 using the MEDLINE (January 1966 to April 2018) and EMBASE (January 1980 to April 2018) databases. Search strategies for the respective procedures are summarized as follows:

Head and neck blocks

For occipital neck blocks, the terms “occipital nerve block”, “occipital nerve blockade”, “occipital block”, “occipital blockade” were searched for using the “title/abstract” field. Articles from the initial search results were manually examined for appropriateness in this review. In the case of cervical plexus block, an initial strategy of combining the MeSH terms “cervical plexus” and “nerve block” yielded unsatisfactory results as highly relevant articles6,7 were not identified. As a result, the strategy was altered to query the “title/abstract” data field instead of MeSH terms. The query string used was “cervical plexus block” OR “cervical plexus nerve block” OR “cervical plexus blockade”. Articles were manually selected from the initial results for appropriateness in this review. After selecting the initial articles, we examined the respective reference lists for additional material.

Upper limb blocks

MeSH terms “brachial plexus block”, “radial nerve”, “median nerve” and “ulnar nerve” were searched for and combined with the MeSH term “nerve block” using the operator “AND”. Since “interscalene”, “supraclavicular”, “retroclavicular”, “infraclavicular”, “costoclavicular”, “axillary”, “suprascapular”, and “axillary nerve” are not MeSH terms, they were queried as keywords and combined with the MeSH term “nerve block”. From this initial search, only reports of bleeding/aneurysmal complications were retained. We also collected reports from any study or database with > 200 patients that assessed the frequency of vascular puncture with a particular upper extremity regional anesthesia technique. After selecting the initial articles, we examined the respective reference lists for additional material.

Lower limb blocks

MeSH terms “lumbosacral plexus”, “femoral nerve”, “obturator nerve”, “saphenous nerve”, “sciatic nerve”, “peroneal nerve”, and “tibial nerve” were searched for and combined with the MeSH term “nerve block” using the operator “AND”. Since “lumbar plexus”, “psoas compartment”, “psoas sheath”, “sacral plexus”, “fascia iliaca”, “three-in-one”, “3-in-1”, “femoral triangle”, “adductor canal”, “lateral femoral cutaneous”, “posterior femoral cutaneous”, “ankle”, and “ankle block” are not MeSH terms, they were queried as keywords and combined with the MeSH term “nerve block”. From this initial search, only reports of bleeding/aneurysmal complications were retained. After selecting the initial articles, we examined the respective reference lists for additional material.

Interfascial plane blocks

The terms “interfascial plane block”, “transversus abdominis plane block”, “serratus plane block”, “subcostal TAP block”, “posterior TAP block”, “four quadrant TAP block”, “dual TAP block”, “LM-TAP”, “lateral TAP block”, “rectus sheath block”, “quadratus lumborum block”, “QLB”, “PECS 1 block”, “PECS 2 block”, “PECS block”, “pectoral nerve block”, “serratus plane block”, “ilioinguinal nerve”, “iliohypogastric nerve”, “ilioinguinal nerve block”, “iliohypogastric nerve block”, “erector spinae plane block”, and “thoraco-lumbar interfascial plane block” were searched for and combined with the keywords “hemorrhage” or “hematoma” or “vascular system injuries” using the operator “AND”. The strategy to combine bleeding and nerve block-related search terms returned few results. Accordingly, all abstracts from the reports of interfascial blocks were manually reviewed to seek reports of procedural complications such as hematoma, bleeding, or visceral injury. The full text of studies reporting block-related complications were retrieved for data extraction with selected articles then categorized into prospective studies or case reports/case series. After selecting the initial articles, we examined the respective reference lists for additional relevant material.

Truncal blocks

For paravertebral block, the MeSH terms “nerve block” OR “conduction anesthesia” were searched for and combined with the keywords “regional anesthesia”, “regional anaesthesia”, “conduction block” OR “conduction anaesthesia” using the operator “OR”. The results of this search were combined with the keywords “paravertebral” OR “paravertebral block” using the operator “AND”. Articles from the initial search were manually examined for appropriateness in this review. In the case of intercostal block, the MeSH terms “nerve block” OR “conduction anesthesia” were searched for and combined with the keywords “regional anesthesia”, “regional anaesthesia”, “conduction block” OR “conduction anaesthesia” using the operator “OR”. The results of this search were combined with the keywords “intercostal” OR “intercostal block” using the operator “AND”. Similarly, all results from this initial search were manually reviewed for appropriateness in this review. After selecting the relevant articles from each search, we examined the respective reference lists for additional relevant material.

Evidence review and risk classification consensus

Head and neck blocks

Evidence review

Occipital nerve block

Both the greater and lesser occipital nerves can be blocked by superficial injections in the posterior neck along the inferior nuchal line.8 While the occipital artery is adjacent to the greater occipital nerve, it is commonly assumed that significant bleeding complications are rare because of the superficial nature of this block.

Eighty-one original articles involving occipital nerve blocks were identified. The majority involved isolated greater occipital nerve block (73 articles) or combined greater and lesser occipital nerve blocks (six articles). Jurgens et al. reported that two out of 20 study patients developed mild localized bleeding after greater occipital nerve blocks for craniofacial neuralgias.8 Similar mild bleeding occurred in two studies where patients received greater occipital nerve blocks for headaches.9,10,11 None of these bleeding complications resulted in invasive intervention or prolonged adverse effects.

Cervical plexus block (superficial/intermediate/deep)

Traditionally, cervical plexus blocks are classified as superficial (subcutaneous injection at the midpoint of the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle) or deep (injections next to C2–C4 transverse processes deep to the prevertebral fascia).12 More recently an “intermediate” approach has been proposed,12,13 where local anesthetic is injected deep to the investing fascia of the neck rather than the subcutaneous injection employed in the superficial approach.

In total, 209 articles were identified relating to the various depths of cervical plexus block. There were no reported cases of bleeding complications arising from cervical plexus blocks in the literature, regardless of approach. Several articles reported neck hematoma formation postoperatively after carotid endarterectomy, thyroidectomy, or maxillofacial surgery.7,14,15,16 Nevertheless, all of these hematomas were attributed to surgical complications rather than the block itself. The only block-related bleeding complication reported was not due to direct needle trauma.17 Instead, a combined superficial plus deep cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy inadvertently caused a recurrent laryngeal nerve block. Subsequent aspiration and coughing led to surgical site bleeding and hematoma formation.

Risk classification consensus

Occipital nerve block

The occipital nerves are located in an area that is easily compressible should bleeding occur. Even were significant bleeding to occur, the posterior scalp is devoid of any major structure that would be at risk from the mass effect of a hematoma. The evidence confirms that the occipital nerve block is a safe procedure with a low risk of bleeding complications as all bleeding/hematoma cases in the literature were self-limiting and required no interventions. The panel therefore recommends that the occipital nerve block be classified as low risk for bleeding complications.

Cervical plexus block

There is minimal evidence in the literature to guide risk stratification for the different approaches to the superficial cervical plexus block. In all approaches, the needle should only traverse the superficial tissue layers and its tip should remain superficial to the prevertebral fascia. As such, any bleeding will be easily assessable and compressible, and the mass effect of a hematoma in this location will be insignificant. The panel therefore recommends that the superficial cervical plexus block be classified as low risk for bleeding complications.

The bleeding risk for deep cervical plexus block is less clear. While there are no reports of significant bleeding directly resulting from deep cervical plexus blocks, various critical anatomical structures are at potential risk of injury when the needle penetrates the prevertebral fascia. These include blood vessels such as the vertebral artery, dorsal scapular artery, and suprascapular artery. There are reports of direct injection of local anesthetic into the vertebral artery18,19,20 and subarachnoid space20,21 during deep cervical plexus blocks. Bleeding from these deeper vessels may be occult, difficult to tamponade non-invasively, and the mass effect from an expanding hematoma in the neck could have significant consequences. The panel therefore recommends that the deep cervical plexus block be classified as high risk for bleeding complications.

One of the most common indications for cervical plexus block is anesthesia or analgesia for carotid endarterectomy. This population warrants special consideration as the pathology often dictates that the patients remain on antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapies up to the time of surgery. A prospective case series reported no bleeding complications with patients taking antiplatelet/anticoagulation medications at the time of the superficial plus deep cervical plexus blocks.22 The panel recommends that the decision to perform cervical plexus blocks in this population should rest on a careful assessment of specific risks and benefits applicable to the individual patient and practitioner.

Upper limb blocks

Evidence review

Interscalene block

Despite the superficial location, there are many arterial structures in the interscalene region of the neck, including the dorsal scapular, transverse cervical, and vertebral arteries, any of which may be punctured during needle advancement.

In large (> 200 patients) prospective and retrospective databases, there is a low incidence of vascular puncture during interscalene block, with reported rates between 0 and 0.63%.23,24,25,26,27,28,29 These databases together captured more than 5,700 interscalene blocks and reported no cases of hematoma. Nevertheless, it is possible that the incidence of both vascular puncture and hematoma are under-reported. There are three case reports of hematoma30,31,32 after interscalene block, though none of these occurred using an ultrasound-guided technique. There have been six spinal cord injuries33,34,35,36 reported after interscalene block, representing severe injury to a critical structure in close proximity to the needle position. Again, none of the reported spinal cord injuries occurred in the context of an ultrasound-guided technique.

Supraclavicular block

There are many arterial structures in the supraclavicular region, including the subclavian, dorsal scapular, and transverse cervical, which may be at risk during needle advancement.

In large (> 200 patients) prospective and retrospective databases, the incidence of vascular puncture during supraclavicular block was noted to be between 0 and 0.4% with no reported hematomas.23,37 Similarly, there are no published case reports of hematoma following supraclavicular block.

A single report of a patient who was receiving argatroban for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and underwent an ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block for postoperative analgesia described good analgesic effect and no hematoma or neurologic complications.38

Retroclavicular brachial plexus block

Though vascular puncture has been described during ultrasound-guided retroclavicular brachial plexus block,39 there have been no reports of other bleeding complications or hematoma formation. Nevertheless, this block was only recently described and reports of bleeding complications or hematoma may therefore be under-reported. Furthermore, the blind initial needle pass with this technique does not allow for the advantage of ultrasound visualization of arteries and veins over the entire needle path.

Infraclavicular brachial plexus block

The infraclavicular brachial plexus lies deep and inferior to the clavicle. While surrounding vascular structures including the axillary artery, axillary vein, and cephalic vein can routinely be anticipated, visualized, and avoided using ultrasound guidance, the risk of vascular puncture remains.

In large (> 200 patients) prospective and retrospective databases, the incidence of vascular puncture during infraclavicular block was noted to be between 0 and 6.6% with nerve stimulator guidance40,41,42 while it was 0.7% with ultrasound guidance,43 with no reports of hematoma formation.

There is only one case report of hematoma after infraclavicular brachial plexus block. This complication occurred in a patient with a history of intravenous drug use and a mechanical mitral valve placed secondary to endocarditis. After withholding anticoagulation, the patient received an ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block. The anticoagulation was subsequently restarted and two weeks postoperatively, the patient presented with an axillary hematoma and two mycotic aneurysms.44

Conversely, there is one case report of a patient who underwent an ultrasound-guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block for analgesia and sympathectomy while on therapeutic heparin after hand reimplantation.45 Though no bleeding resulted, it was noted that the surgeon was prepared to stop the heparin were an expanding hematoma to develop.

Axillary brachial plexus block

The axillary brachial plexus is the most distal site at which all of the sensory branches of the distal upper extremity can be targeted with a single needle insertion. Vascular puncture is a risk because of the multiple axillary veins and the axillary artery, all of which lay adjacent to the nerves of the brachial plexus at the level of the conjoint tendon. Nevertheless, the site is readily compressible, thus vascular puncture is usually of little clinical consequence, as evidenced in part by the time-honoured transarterial technique of axillary brachial plexus blockade.

Only one study of 605 patients examined the occurrence of inadvertent vascular puncture in nerve stimulator-guided axillary brachial plexus blocks and reported an overall incidence of 8.4%. Nevertheless, the rate was three times higher in obese than in non-obese patients within this cohort.46 Two large studies (1,346 patients in total) explored hematoma rates after transarterial axillary brachial plexus block. While one noted “no serious adverse reaction”,47 the other described a 0.2% incidence of small hematomas (0–2 cm).48 No other bleeding complications were noted in either study. Another trial assessed the combination of paresthesia and transarterial techniques for axillary brachial plexus block and found a 12% incidence of “axillary tenderness and bruising”.49

No studies or databases with > 200 patients have reported inadvertent vascular puncture in ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block. Nevertheless, based on smaller studies (29–64 patients per group), the incidence of vascular puncture is between 0 and 15%.50,51,52,53,54,55,56 No hematoma was recorded in any of these studies.

Hematoma formation has been noted in several studies and case reports using the paresthesia, nerve stimulation, or landmark-guided approaches.49,57,58,59,60 Nevertheless, only one “minor hematoma” has been documented when using an ultrasound-guided technique.53

Other blocks of the upper extremity

To date, no bleeding complications have been reported with suprascapular nerve block, axillary nerve block, or distal blocks of the median, ulnar or radial nerves, either with or without the use of ultrasound.

Risk classification consensus

Interscalene and supraclavicular brachial plexus block

Despite substantial vascularity in the region, the literature review would suggest a low incidence of vascular puncture and bleeding complications. With appropriate education and training, common vascular structures may be anticipated, visualized, and avoided with ultrasound guidance.61 If vascular puncture does occur, pressure can be readily applied to limit bleeding. Nevertheless, if a large expanding hematoma does occur, it could have serious consequences, including airway compromise. The panel therefore recommends that the interscalene and supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

Infraclavicular and retroclavicular brachial plexus block

The infraclavicular brachial plexus lies in a richly vascular area, but the literature review suggested that bleeding complications are low. Application of direct pressure to limit hematoma formation can be challenging and may require not only anterior to posterior thoracic pressure but also lateral to medial pressure via the axilla. The panel therefore recommends that the infraclavicular and retroclavicular brachial plexus blocks be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

Axillary brachial plexus block

Although one study (involving 200 patients) of a landmark-based approach noted a 12% incidence of axillary tenderness and bruising,49 hematoma formation following ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block was infrequent. The panel therefore recommends that the axillary brachial plexus block be classified as low risk for bleeding complications. Despite this, it is important that caution be exercised to avoid unnecessary vessel puncture while performing blocks in this vascular rich area.

Distal (median, ulnar, and radial) nerve blocks

There are no case reports of bleeding complications following blocks of the median, radial, or ulnar nerves, as the block sites are relatively superficial and easily compressible. Ultrasound guidance may allow visualization and avoidance of these blood vessels and thus likely decreases the risk of bleeding complications. The panel therefore recommends that distal blocks of the ulnar, median, or radial nerves be classified as low risk for bleeding complications.

Lower extremity blocks

Evidence review

With the exception of a single retroperitoneal hematoma reported in the context of a prospective series,28 the literature search yielded only case reports of bleeding or aneurysmal complications after lower extremity blocks.64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72 The reported complications from these articles are summarized in Table 7.

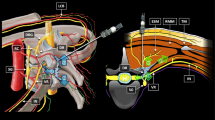

Lumbar plexus block

More than half of the reported bleeding complications after lower limb nerve blocks have occurred in the setting of loss of resistance or neurostimulation-guided lumbar plexus blocks.62,63,64,65,66,67 Clinical sequelae have included psoas hematoma with lumbar plexopathy,63 retroperitoneal hematoma,64,65,66,67 and renal subcapsular hematoma.62 In many cases where complications have occurred, the block was technically difficult and multiple attempts were required.63,65,66,67 Furthermore, administration of anticoagulants (heparin, low molecular weight heparin) and/or acetylsalicylic acid was also noted in more than half of the patients.63,64,65,66 Fortunately, in most instances, the hematoma resolved without invasive intervention or neurologic impairment. Nevertheless the resolution process was slow and required weeks66,67 to months.62,63,65

Femoral block

Although the femoral nerve is superficially situated, its proximity to the femoral artery has (presumably) led to the occurrence of retroperitoneal hematoma following perineural catheter placement.27 Furthermore, intraneural hematoma68 has also been reported in one patient with undiagnosed factor XI deficiency after neurostimulation-guided femoral nerve block. Despite aggressive management with surgical decompression, persistent neurologic impairment was observed in both cases.27,68

Other nerve blocks of the lower extremity

Thigh hematoma and pseudoaneurysm of a collateral branch of the superficial femoral artery have been reported after anterior sciatic and adductor canal blocks, respectively.69,70 The patient undergoing the anterior sciatic nerve block had received fondaparinux and the neurostimulation-guided block was reported to be technically difficult, requiring multiple attempts [69]. While the adductor canal block was performed under ultrasound guidance, the pseudoaneurysm occurred following placement of a perineural catheter.70 Although the thigh hematoma resolved spontaneously,69 the pseudoaneurysm required embolization.70 Fortunately, no permanent sequelae were noted following either case.

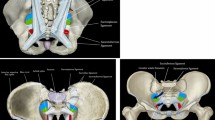

To date, the English-language literature contains no reports of major bleeding complications after lateral femoral cutaneous blocks, obturator nerve blocks, or other approaches to the sciatic nerve block. Nevertheless, the absence of evidence for complications should not be interpreted as evidence of absence of complications. For instance, although lateral femoral cutaneous blocks are performed in a superficial and avascular area, the same may not hold true for deeper procedures such as the parasacral sciatic nerve block. In fact, the latter’s perceived “safety” may attest more to a lack of popularity among anesthesiologists rather than true innocuity.

Risk classification consensus

Deep lower limb blocks

The available literature suggests that lower extremity blocks targeting nerves or plexi situated deep to the skin and close to vital non-compressible structures (e.g., kidney, retroperitoneum, pelvic organs) be considered high risk. These areas are richly vascularized, not easily compressible in the event of vascular puncture, and the clinical diagnosis of an expanding hematoma can be difficult. The panel therefore recommends that lumbar plexus and parasacral sciatic nerve blocks be classified as high risk for bleeding complications.

In contrast, blocks that target nerves or plexi situated deep to the skin but far from vital structures carry a lower risk of significant consequences following bleeding and hematoma formation. The panel therefore recommends that transgluteal sciatic, subgluteal sciatic, anterior sciatic, obturator, and suprainguinal fascia iliaca (i.e., “bow-tie”) blocks be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

Superficial lower limb blocks

Blocks targeting superficial nerves allow ease of compressibility in the event of bleeding. As such, vascular puncture occurring during performance of the femoral nerve, femoral triangle, adductor canal, lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, infrainguinal fascia iliaca, popliteal sciatic nerve, and ankle blocks should not cause significant bleeding complications if detected and treated early. The incidence of vascular puncture will also depend on the guidance modality (e.g., neurostimulation vs ultrasound guidance). The advantage of ultrasonography to visualize normal and aberrant vessels has been highlighted for the popliteal sciatic location,71 and may allow the operator to plan for a safer needle trajectory or to select an alternative approach. The risk assessment should be modified in obese patients in whom the structures may lie much deeper than usual; this increases the risk of inadvertent vascular puncture and may hinder effective compression of the bleeding site.

The panel recommends that lower extremity blocks performed close to large vessels (femoral nerve, adductor canal, and popliteal sciatic nerve blocks) be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications. The panel recommends that blocks of nerves in a very superficial location (lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, infrainguinal fascia iliaca, and ankle blocks) be classified as low risk for bleeding complications.

Interfascial plane blocks

Evidence review

The literature search identified 1,207 publications. After manual review, only reports of bleeding or aneurysmal complications and visceral or peritoneal injury were retained, yielding 16 relevant publications.72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87 The reported complications from these articles are summarized in Table 8. A majority of the studies that prospectively examined complications following interfascial blocks were unclear in their approach to measurement and were excluded because data was lacking. Most reports of complications during interfascial blocks are therefore derived from case series and case reports.

Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block

Two reports acknowledged bleeding-related complications after TAP block procedures including a case of vascular puncture79 and an intramuscular hematoma in a patient with peripartum coagulopathy.81 A total of four additional reports acknowledged non-bleeding but relevant complications related to TAP block procedures.76,78,79,87 These included peritoneal puncture,76,79 liver injury with peritonitis,78,87,88,89,90 and an unknown complication in a patient with a high BMI.75 When the blocks were performed before the surgical incision, complications were recognized during the subsequent laparotomy/laparoscopy. With blocks performed at the end of surgery, advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) scanning was required. The use of ultrasound and blunt tip block needles during the performance of these blocks was confirmed in four of six reports. All reported complications were managed conservatively and did not require additional intervention.

Ilioinguinal iliohypogastric nerve (IIN/IHG) block

Five case reports noted complications following IIN/IHG blocks,72,74,77,80,84 including one instance each of intrapelvic hematoma84 and retroperitoneal hematoma,80 as well as three reported cases of bowel injury.72,74,77 All IIN/IHG blocks performed in these five cases employed a double-pop technique. While in the case of retroperitoneal hematoma the patient was concurrently taking antiplatelet medications, the case of intrapelvic hematoma had no history of coagulopathy or medications altering coagulation. Both these complications required a CT scan for diagnosis following signs and symptoms of pain and blood loss. The patient with retroperitoneal hematoma experienced an injury to the deep circumflex iliac artery, which required embolization, while the case of intrapelvic hematoma was managed conservatively. Of the three patients developing bowel injury, two cases were recognized intraoperatively and managed with minimal surgical intervention74,77 while the third case was identified five days later following signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction and required small bowel excision.72

Rectus sheath block

Two reports noted complications secondary to rectus sheath blocks, both of which were performed using the loss of resistance technique.85,86 While the complication in one report was limited to intraperitoneal injection,86 the other resulted in retroperitoneal hematoma.85 During this later block, blood aspiration was noted during the procedure and the block was abandoned. The patient underwent postoperative CT imaging to determine the extent of the complication but was managed conservatively without the need for any further intervention.

Pectoral nerve (PECS) blocks

Two reports noted bleeding complications following a PECS block.73,83 In a randomized-controlled trial (RCT) of 127 patients receiving a PECS-1 block, three patients (2.3%) were noted to have bleeding and pectoral hematoma,73 while in another observational study of PECS block, eight of 498 patients (1.6%) developed a pectoral hematoma.83 Of the eight patients in this later report who developed a bleeding complication, five were on either an oral anticoagulant or an antiplatelet medication.

Other newer blocks

No published hematologic complications have been noted with the newer interfascial plane (transversalis fascia plane, serratus anterior, retrolaminar, quadratus lumborum, and erector spinae plane) blocks91,92 but this may simply reflect the limited experiences with these newer techniques. Further, the manifestation of hematologic complications with these newer blocks may be varied as exemplified with the recent reporting of quadratus lumborum hematomas in a pediatric population.93 One of the two patients having the complication received heparin 3.5 hr following the block while the coagulation status was not altered in the other patient. Both these complications resulted in lumbar pain out of proportion to surgical pain and manifested as bruising in the lumbar region a few days following these blocks, highlighting the delayed presentation of hematologic complications following the quadratus lumborum block.

Risk classification consensus

Although the interfascial plane blocks have been safely performed in patients receiving anticoagulation or on antiplatelet therapy, the risk of vascular or visceral injury and the related bleeding risks remain significant possibilities.

While the TAP blocks, IIN/IHG blocks, PECS block, serratus anterior blocks, and the rectus sheath blocks are superficial, serious complications such as bleeding, visceral injury, peritonitis, and hematoma have been reported in the literature. In applying the CIA scoring tool, blood vessels within the fascial plane and the viscera deeper may be deemed critical structures. Furthermore, the complications noted with many of these blocks were not immediately detected and were either recognized at laparotomy or following CT imaging for symptomatic patients. Most of the complications were managed conservatively and did not need additional interventions.

Given the risk of hematoma and visceral injury, the panel agreed that TAP blocks, rectus sheath blocks, and IIN/IHG blocks in patients at risk of bleeding should be performed using guidance techniques such as ultrasonography by personnel with adequate experience. The panel recommends that these blocks be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

The transversalis fascia plane block is very similar in anatomy and approach to a TAP block, and thus the panel recommends that it be similarly classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

The quadratus lumborum block, on the other hand, is a deeper block with a needle trajectory into a non-compressible space. The risk of bleeding complications and visceral injury may thus be considered similar to that of the lumbar plexus block, although there are sparse published data to either support or refute this. The panel therefore currently recommends that the quadratus lumborum block be classified as high risk for bleeding complications.

Pectoral nerve blocks and the other newer anterior chest wall blocks have only been described employing ultrasound guidance and the consequences of complications are at present unclear.

Based on the location of injection deep to the pectoral muscles, and the presence of nearby vascular structures such as the thoracoacromial artery, the panel recommends that these blocks be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

Bleeding complications or visceral injury with newer blocks, such as retrolaminar or erector spinae plane blocks, have not been reported. Hence, because there are no critical structures in close proximity, the panel recommends that these blocks be classified as low risk for bleeding complications.

Truncal blocks

Evidence review

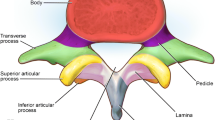

Paravertebral block

The paravertebral space can be accessed from a number of approaches that follow anatomic landmarks or employ ultrasound guidance. The region of the paravertebral space is richly vascular with each of the intercostal nerves and vasculature travelling to some degree within this compartment. In addition, the lung and major vessels deep to the space contribute to anatomic complexity with these blocks. Paravertebral blocks are among the most widely described and reported regional procedures over many decades, with few overall bleeding complications reported.

In this review, the search strategy identified 1,574 articles, which underwent manual review. A number of large retrospective studies have reported on local experience. Three such reports totalling 3,215 blocks identified no bleeding complications.94,95,96 Nevertheless, an additional series of 620 adult patients describe inadvertent vascular puncture in 6.8% of the procedures and superficial hematoma requiring external compression in 2.4%.97

Most bleeding complications associated with paravertebral blocks have been reported as secondary outcomes in unrelated trials. Inadvertent vascular puncture in particular has been reported in 13 publications.98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110 These were reported across a range of adult and pediatric populations, under anatomic and ultrasound guidance, during single shot and catheter blocks, and with rates in these reports of between one-in-527102 and one-in-eight.105 None of these cases resulted in serious bleeding outcomes, despite the presence of therapeutic anticoagulation in two reports.101,102 Of note, an additional case report describes vascular puncture of a thoracic aneurysm during single shot block, fortunately without catastrophic outcome.111 Superficial bleeding that did not require intervention has been reported in five publications102,112,113,114,115 exclusively in procedures performed using Tuohy needles for catheter placement. Bleeding in this location may be unrecognized superficially and one case series describes five of 26 patients (who received a percutaneous catheter via an 18G Tuohy needle) developing a hematoma that was visually confirmed internally during the video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) procedure.116 No intervention was necessary in these cases. Finally, one case report describes frank pulmonary hemorrhage detected via the endotracheal tube with concurrent spinal and periaortic hematoma found on a follow-up CT scan.117 This complication occurred in a patient with previous thoracotomy, leading to compromise of the paravertebral space by postsurgical scarring. The patient was managed conservatively.

Despite these reports, paravertebral blocks have been described in 13 publications as interventions specifically for anticoagulated patients. These publications include cardiac surgery patients,101,112,118,119 pre-existing coagulopathies,114,120,121,122 thrombocytopenia,123,124 and antiplatelet medications.102,125,126 No serious complications occurred in any of these reports.

Intercostal block

The intercostal nerves run in close approximation to the vascular bundle of the intercostal artery and vein, along the intercostal groove on the ventral caudal surface of each rib.127 While the location of these structures is superficial relative to the skin, the thoracic cavity below the pleura represents a large and hidden compartment in which blood may accumulate.

The search strategy returned 1,355 articles, which were manually reviewed for relevance. Large numbers of intercostal blocks have been reported without bleeding complications. In one study, 50,097 individual blocks in 4,333 patients were described without a single bleeding complication.128 Furthermore, case series and case reports have been described in anticoagulated, high bleeding risk patients without adverse outcomes.129,130 Nevertheless, three case reports highlight potential risks.131,132,133 One patient without bleeding risk factors received a series of diagnostic single shot blocks, followed by a catheter insertion, and subsequently a final single shot anatomic-guided block. After the catheter placement, a superficial hematoma was noted and the catheter was removed. Two weeks later, the single shot injection resulted in a 1,000 mL hemothorax that required drainage followed by conservative management. The hemothorax was detected after symptoms consistent with large volume blood loss led to a thoracic CT scan.131 Two additional case reports describe massive chest wall and flank hematomas that developed following intercostal nerve block in patients with impaired coagulation.132,133 In both cases, the bleeding was easily visible superficially and was managed conservatively. During a series of fluoroscopic-guided intercostal steroid injections, intravascular spread was noted in two out of 26 patients but without reported bleeding complications.134 Finally, during VATS in a series of 24 patients receiving intercostal catheters, local hematoma was observed when the chest was opened in two patients. Of note, pain in these patients was significantly higher in the postoperative period although no intervention for the bleeding was necessary.116

Risk classification consensus

Paravertebral block

The paravertebral space is a non-accessible and non-compressible space with a number of critical structures in close proximity. As such it has all the characteristics of a high-risk regional technique. In addition, bleeding within the space, or into the thoracic cavity is not readily detectable on clinical examination.116 The panel therefore recommends that paravertebral blocks be classified as high risk for bleeding complications. Nevertheless, we note that numerous authors have employed this block specifically as an alternative to neuraxial blockade in patients at high risk of bleeding complications.101,102 There may be circumstances where this block is an appropriate choice, even in patients at elevated risk of bleeding complications. Nevertheless this decision should be taken after careful consideration of the risk:benefit ratio and the expertise of the practitioner.

Intercostal block

Although the available literature reports only a small number of cases with bleeding complications, the degree of hemorrhage and size of hematoma formation reported in these cases is large. Furthermore, bleeding into the thoracic cavity may remain occult until hemodynamic effects from large volume blood loss are evident.131 In cases where bleeding complications have been noted, conservative management was the most common approach, although in one instance, evacuation of hemothorax was required. This risk of intrathoracic bleeding combined with difficulty in compressing the intercostal space increases the potential for negative outcome. While the distance from the neuraxis may presumably reduce the impact of any hematoma on the critical structures in this region, no evidence exists to guide clinical decisions based on this consideration. As a result of these issues, the panel recommends that intercostal blocks be classified as intermediate risk for bleeding complications.

Discussion

The consensus advisory recommendations are summarized in Table 3. Relevant key information from the cited references is summarized in Tables 4-9 according to anatomic regions. In recognition of the lack of systematic studies assessing the risk of bleeding complications as a primary outcome, data on bleeding complications reported as secondary outcomes in RCTs or cohort studies were assigned the same level of evidence as case report data.

In patients with an elevated risk of bleeding complications due to coagulopathy, anticoagulation, or antithrombotic therapy, the panel generally recommends the following:

-

Low risk: The risk of bleeding complications is expected to be low. Although rare events cannot be excluded, they are expected to be easily managed.

-

Intermediate risk: The risk of bleeding complications is a genuine possibility. The decision to perform a block should be made on a case-by-case basis after evaluating the risks and benefits of the block. The procedure should be performed by experienced personnel with additional monitoring of the block technique and potential complications. Monitoring aids should include ultrasound guidance for the block performance. The panel also recommends that these blocks be performed in a manner that would aid in early recognition of the complication. For example, TAP blocks or rectus sheath blocks may be performed preoperatively or presurgically rather than postoperatively, as the hematologic complication may be recognized during laparotomy or laparoscopy. The panel also recommends that intermediate risk blocks be monitored for hemodynamic changes and any bleeding manifestations following the procedure until deemed necessary. Routine monitoring such as ultrasound assessment of the block site for any fluid collections over time, impedance monitoring,135 or inclusion of a vascular marker in the local anesthetic mixture may be additional useful aids, but whether they improve the safety profile of block performance is currently unknown.

-

High risk: The bleeding complications may be associated with significant morbidity or may be difficult to detect. Given the risk of bleeding complications and associated sequelae with the procedure, these blocks should be reconsidered if the patient has an elevated bleeding risk—i.e., these blocks should be avoided in these patients except in exceptional circumstances where the benefits clearly outweigh the increased complication risk.

High-quality evidence is lacking, therefore the recommendations of this practice advisory are largely contingent on expert opinion rather than being evidence based. Indeed, the level of evidence for the bleeding risks and complications for most procedures is either very low or nonexistent. This may be in part due to the rarity of these events, making studies evaluating them hard to design. Apart from the rarity of trials evaluating complication rates as a primary outcome measure, there is also a significant reporting and publication bias for case reports especially those which do not report positive outcomes.136,137 This often requires non-traditional data collection methods and analysis leading to potentially very poor external validity.138 Such prospective studies, while important to the quality improvement perspective of our practice are unfortunately sparse in regional anesthesia literature. One of the reasons for the rare occurrence of bleeding complications may be the enhanced safety from the implementation of guidelines in the management of patients with altered coagulation undergoing regional anesthesia. Nevertheless, one of the potential limitations of this work was that we chose our literature search to include only MEDLINE and EMBASE. While we believed that it would encompass the majority of the available literature, one may argue that additional database searches potentially strengthen the evidence for our recommendations. Given the absence of available clinical data, whether or not such a broader search strategy would have increased the number of unique references remains uncertain.139,140

Conclusions

Bleeding complications following regional peripheral nerve and interfascial plane blocks are rare, but when present, they may lead to significant patient morbidity and the need for further investigations and interventions. The risk of bleeding complications following regional anesthesia procedures depends on the degree of trauma produced by the needle, patient coagulation status, and the type of block. The present advisory describes the risk and subsequent clinical implications from the perspective of the individual type of block. The risk of bleeding complications and the subsequent sequelae vary between blocks. This needs to be weighed against the potential benefits, while offering these procedures on a case-by-case basis. The paucity of evidence in anticoagulated patients does not necessarily translate into a lower risk of bleeding complications as most of these blocks will not routinely be offered to such patients given existing regional anesthesia guidelines.

The best efforts of the panel were employed to categorize bleeding risk for peripheral regional anesthesia procedures using published evidence combined with the panel’s clinical experience. Nevertheless, the actual risk of a given procedure is indeterminate and the quality of published evidence for most blocks remains low. The ratings are in part based on theoretical principles and consensus because sufficient evidence from quality-controlled studies was absent. The risks categories determined by applying this methodology should therefore not be construed as absolute and the consensus will be subject to periodic revision as warranted by evaluation of the evolving knowledge base. Hence, it is critical to reemphasize that many recommendations stated here are based on limited or nonexistent clinical data. As such, interpretation of the literature by this panel may differ from that of other equally qualified experts. More importantly, the clinician must exercise their clinical judgement when determining the risks and benefits in individual patient cases and how to proceed should inadvertent vascular puncture be noted.

Given these facts, readers of this consensus advisory should be reminded that these recommendations are not to be defined as a standard of care but rather serve as a resource for clinicians assessing the risk and benefits of regional anesthesia in management of their patients.

References

Horlocker TT, Vandermeuelen E, Kopp SL, Gogarten W, Leffert LR, Benzon HT. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Fourth Edition). Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018; 43: 263-309.

Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano DA, et al. Interventional spine and pain procedures in patients on antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications: guidelines from the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40: 182-212.

Bolash RB, Rosequist RW. Regional anesthesia and anticoagulation. In: Finucane B, Tsui BC, editors. Complications of Regional Anesthesia, Principles of Safe Practice in Local and Regional Anesthesia. 3rd ed. NY: Springer; 2017. p. 139-48.

Tsui BC. A systematic approach to scoring bleeding risk in regional anesthesia procedures. J Clin Anesth 2018; 49: 69-70.

Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med 1999; 170: 348-51.

Kim JS, Lee J, Soh EY, et al. Analgesic effects of ultrasound-guided serratus-intercostal plane block and ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical plexus block after single-incision transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41: 584-8.

Alilet A, Petit P, Devaux B, et al. Ultrasound-guided intermediate cervical block versus superficial cervical block for carotid artery endarterectomy: the randomized-controlled CERVECHO trial. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2017; 36: 91-5.

Jürgens TP, Müller P, Seedorf H, Regelsberger J, May A. Occipital nerve block is effective in craniofacial neuralgias but not in idiopathic persistent facial pain. J Headache Pain 2012; 13: 199-213.

Na SH, Kim TW, Oh SY, Kweon TD, Yoon KB, Yoon DM. Ultrasonic doppler flowmeter-guided occipital nerve block. Korean J Anesthesiol 2010; 59: 394-7.

Naja Z, Al-Tannir M, El-Rajab M, Ziade F, Baraka A. Nerve stimulator-guided occipital nerve blockade for postdural puncture headache. Pain Pract 2009; 9: 51-8.

Sahin BE, Coskun O, Ucler S, Inan N, Inan LE, Ozkan S. The responses of the greater occipital nerve blockade by local anesthetics in headache patients. J Neurol Sci 2016; 33: 20-9.

Pandit JJ, Dutta D, Morris JF. Spread of injectate with superficial cervical plexus block in humans: an anatomical study. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 733-5.

Telford RJ, Stoneham MD. Correct nomenclature of superficial cervical plexus blocks. Br J Anaesth 2004; 92: 775-6.

Ucci A, D’Ospina RM, Fanelli M, et al. One-year experience in carotid endarterectomy combining general anaesthesia with preserved consciousness and sequential carotid cross-clamping. Acta Biomed 2018; 89: 61-6.

Egan RJ, Hopkins JC, Beamish AJ, Shah R, Edwards AG, Morgan JD. Randomized clinical trial of intraoperative superficial cervical plexus block versus incisional local anaesthesia in thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Br J Surg 2013; 100: 1732-8.

Perisanidis C, Saranteas T, Kostopanagiotou G. Ultrasound-guided combined intermediate and deep cervical plexus nerve block for regional anaesthesia in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2013; 42: 29945724.

Harris RJ, Benveniste G. Recurrent laryngeal nerve blockade in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy under cervical plexus block. Anaesth Intensive Care 2000; 28: 431-3.

Fielmuth S, Uhlig T. The role of somatosensory evoked potentials in detecting cerebral ischaemia during carotid endarterectomy. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2008; 25: 648-56.

Hakl M, Michalek P, Ševcik P, Pavlikova J, Stern M. Regional anaesthesia for carotid endarterectomy: an audit over 10 years. Br J Anaesth 2007; 99: 415-20.

de Sousa AA, Filho MA, Faglione W Jr, Carvalho GT. Superficial vs combined cervical plexus block for carotid endarterectomy: a prospective, randomized study. Surg Neurol 2005; 63(Suppl 1): S22-5.

Basagan-Mogol E, Goren S, Tokat O, Uckunkaya N. Acute respiratory distress after cervical plexus block caused by acute brainstem anaesthesia. Pain Clin 2005; 17: 331-4.

Davies MJ, Murrell GC, Cronin KD, Meads AC, Dawson A. Carotid endarterectomy under cervical plexus block - A prospective clinical audit. Anaesth Intensive Care 1990; 18: 219-23.

Liu SS, Gordon MA, Shaw PM, Wilfred S, Shetty T, Yadeau JT. A prospective clinical registry of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia for ambulatory shoulder surgery. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 617-23.

Taenzer A, Walker BJ, Bosenberg AT, et al. Interscalene brachial plexus blocks under general anesthesia in children: is this safe practice? A report from the Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (PRAN). Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014; 39: 502-5.

Orebaugh SL, Williams BA, Vallejo M, Kentor ML. Adverse outcomes associated with stimulator-based peripheral nerve blocks with versus without ultrasound visualization. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 251-5.

Ekatodramis G, Macaire P, Borgeat A. Prolonged Horner syndrome due to neck hematoma after continuous interscalene block. Anesthesiology 2001; 95: 801-3.

Wiegel M, Gottschaldt U, Hennebach R, Hirschberg T, Reske A. Complications and adverse effects associated with continuous peripheral nerve blocks in orthopedic patients. Anesth Analg 2007; 104: 1578-82.

Pöpping DM, Zahn PK, Van Aken HK, Dasch B, Boche R, Pogatzki-Zahn EM. Effectiveness and safety of postoperative pain management: a survey of 18 925 consecutive patients between 1998 and 2006 (2nd revision): a database analysis of prospectively raised data. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101: 832-40.

Bert JM, Khetia E, Dubbink DA. Interscalene block for shoulder surgery in physician-owned community ambulatory surgery centers. Arthroscopy 2010; 26: 1149-52.

Borgeat A, Ekatodramis G, Kalberer F, Benz C. Acute and nonacute complications associated with interscalene block and shoulder surgery: a prospective study. Anesthesiology 2001; 95: 875-80.

Clendenen SR, Robards CB, Wang RD, Greengrass RA. Continuous interscalene block associated with neck hematoma and postoperative sepsis. Anesth Analg 2010; 110: 1236-8.

Howell SM, Unger MW, Colson JD, Serafini M. Ultrasonographic evaluation of neck hematoma and block salvage after failed neurostimulation-guided interscalene block. J Clin Anesth 2010; 22: 560-1.

Benumof JL. Permanent loss of cervical spinal cord function associated with interscalene block performed under general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2000; 93: 1541-4.

Mostafa RM, Mejadi A. Quadriplegia after interscalene block for shoulder surgery in sitting position. Br J Anaesth 2013; 111: 846-7.

Porhomayon J, Nader ND. Acute quadriplegia after interscalene block secondary to cervical body erosion and epidural abscess. Middle East J Anaesthesiol 2012; 21: 891-4.

Yanovski B, Gaitini L, Volodarski D, Ben-David B. Catastrophic complication of an interscalene catheter for continuous peripheral nerve block analgesia. Anaesthesia 2012; 67: 1166-9.

Perlas A, Lobo G, Lo N, Brull R, Chan VW, Karkhanis R. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block: outcome of 510 consecutive cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 171-6.

Khelemsky Y, Rosenblatt MA. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block in a patient anticoagulated with argatroban. Pain Pract 2008; 8: 152.

Charbonneau J, Frechette Y, Sansoucy Y, Echave P. the ultrasound-guided retroclavicular block: a prospective feasibility study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2015; 40: 605-9.

Salazar CH, Espinosa W. Infraclavicular brachial plexus block: variation in approach and results in 360 cases. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1999; 24: 411-6.

Gürkan Y, Hoşten T, Solak M, Toker K. Lateral sagittal infraclavicular block: clinical experience in 380 patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008; 52: 262-6.

Keschner MT, Michelsen H, Rosenberg AD. e Safety and efficacy of the infraclavicular nerve block performed at low current. Pain Pract 2006; 6: 107-11.

Sandhu NS, Manne JS, Medabalmi PK, Capan LM. Sonographically guided infraclavicular brachial plexus block in adults: a retrospective analysis of 1146 cases. J Ultrasound Med 2006; 25: 1555-61.

Gleeton D, Levesque S, Trépanier CA, Gariépy JL, Brassard J, Dion N. Symptomatic axillary hematoma after ultrasound-guided infraclavicular block in a patient with undiagnosed upper extremity mycotic aneurysms. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 1069-71.

Bigeleisen PE. Ultrasound-guided infraclavicular block in an anticoagulated and anesthetized patient. Anesth Analg 2007; 104: 1285-7.

Hanouz JL, Grandin W, Lesage A, Oriot G, Bonnieux D, Gérard JL. Multiple injection axillary brachial plexus block: Influence of obesity on failure rate and incidence of acute complications. Anesth Analg 2010; 111: 230-3.

Aantaa R, Kirvelä O, Lahdenperä A, Nieminen S. Transarterial brachial plexus anesthesia for hand surgery: a retrospective analysis of 346 cases. J Clin Anesth 1994; 6: 189-92.

Stan TC, Krantz MA, Solomon DL, Poulos JG, Chaouki K. The incidence of neurovascular complications following axillary brachial plexus block using a transarterial approach. A prospective study of 1,000 consecutive patients. Reg Anesth 1995; 20: 486-92.

Pearce H, Lindsay D, Leslie K. Axillary brachial plexus block in two hundred consecutive patients. Anaesth Intensive Care 1996; 24: 453-8.

Chan VW, Perlas A, McCartney CJ, Brull R, Xu D, Abbas S. Ultrasound guidance improves success rate of axillary brachial plexus block. Can J Anesth 2007; 54: 176-82.

Vazin M, Jensen K, Kristensen DL, et al. Low-volume brachial plexus block providing surgical anesthesia for distal arm surgery comparing supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary approach: a randomized observer blind trial. Biomed Res Int 2016; 2016: 7094121.

Tran DQ, Pham K, Dugani S, Finlayson RJ. A prospective, randomized comparison between double-, triple-, and quadruple-injection ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012; 37: 248-53.

Frederiksen BS, Koscielniak-Nielsen ZJ, Jacobsen RB, Rasmussen H, Hesselbjerg L. Procedural pain of an ultrasound-guided brachial plexus block: a comparison of axillary and infraclavicular approaches. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2010; 54: 408-13.

Cho S, Kim YJ, Baik HJ, Kim JH, Woo JH. Comparison of ultrasound-guided axillary brachial plexus block techniques: perineural injection versus single or double perivascular infiltration. Yonsei Med J 2015; 56: 838-44.

Bloc S, Mercadal L, Garnier T, et al. Comfort of the patient during axillary blocks placement: a randomized comparison of the neurostimulation and the ultrasound guidance techniques. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010; 27: 628-33.

Tran DQ, Russo G, Muñoz L, Zaouter C, Finlayson RJ. A prospective, randomized comparison between ultrasound-guided supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary brachial plexus blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 366-71.

Ben-David B, Stahl S. Axillary block complicated by hematoma and radial nerve injury. Reg Anesth Pain Med 1999; 24: 264-6.

Groh GI, Gainor BJ, Jeffries JT, Brown M, Eggers GW Jr. Pseudoaneurysm of the axillary artery with median-nerve deficit after axillary block anesthesia. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990; 72: 1407-8.

Zipkin M, Backus WW, Scott B, Poppers PJ. False aneurysm of the axillary artery following brachial plexus block. J Clin Anesth 1991; 3: 143-5.

Torres Moreta MD, Rosado R, Gilsanz F. Brachial fascial compartment hematoma after brachial plexus anesthesia with axillary nerve stimulation (Spanish). Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2008; 55: 52-3.

Muhly WT, Orebaugh SL. Sonoanatomy of the vasculature at the supraclavicular and interscalene regions relevant for brachial plexus block. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011; 55: 1247-53.

Aida S, Takahashi H, Shimoji K. Renal subcapsular hematoma after lumbar plexus block. Anesthesiology 1996; 84: 452-5.

Klein SM, D’Ercole F, Greengrass RA, Warner DS. Enoxaparin associated with psoas hematoma and lumbar plexopathy after lumbar plexus block. Anesthesiology 1997; 87: 1576-9.

Weller RS, Gerancher JC, Crews JC, Wade KL. Extensive retroperitoneal hematoma without neurologic deficit in two patients who underwent lumbar plexus block and were later anticoagulated. Anesthesiology 2003; 98: 581-5.

Aveline C, Bonnet F. Delayed retroperitoneal haematoma after failed lumbar plexus block. Br J Anaesth 2004; 93: 589-91.

Dauri M, Faria S, Celidonio L, Tarantino U, Fabbi E, Sabato AF. Retroperitoneal haematoma in a patient with continuous psoas compartment block and enoxaparin administration for total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103: 309-10.

Warner NS, Duncan CM, Kopp SL. Acute retroperitoneal hematoma after psoas catheter placement in a patient with myeloproliferative thrombocytosis and aspirin therapy. A A Case Rep 2016; 6: 28-30.

Rodríguez J, Taboada M, García F, Bermudez M, Amor M, Alvarez J. Intraneural hematoma after nerve stimulation-guided femoral block in a patient with factor XI deficiency: case report. J Clin Anesth 2011; 23: 234-7.

Poivert C, Malinovsky JM. Thigh haematoma after sciatic nerve block and fondaparinux (French). Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2012; 31: 484-5.

Cappelleri G, Molinari P, Stanco A. Iatrogenic pseudoaneurysm after continuous adductor canal block. A A Case Rep 2016; 7: 200-2.

Sata S, Vandepitte C, Gobliewski M, Hadzic A. Aberrant vein within common connective tissue sheath of the sciatic nerve at the popliteal fossa. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2014; 39: 82-3.

Amory C, Mariscal A, Guyot E, Chauvet P, Leon A, Poli-Merol ML. Is ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block always totally safe in children? Paediatr Anaesth 2003; 13: 164-6.

Cros J, Sengès P, Kaprelian S, et al. Pectoral I block does not improve postoperative analgesia after breast cancer surgery: a randomized, double-blind, dual-centered controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018; 43: 596-604.

Frigon C, Mai R, Valois-Gomez T, Desparmet J. Bowel hematoma following an iliohypogastric-ilioinguinal nerve block. Paediatr Anaesth 2006; 16: 993-6.

Hotujec BT, Spencer RJ, Donnelly MJ, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block in robotic gynecologic oncology: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol 2015; 136: 460-5.

Jankovic Z, Ahmad N, Ravishankar N, Archer F. Transversus abdominis plane block: how safe is it? Anesth Analg 2008; 107: 1758-9.

Jöhr M, Sossai R. Colonic puncture during ilioinguinal nerve block in a child. Anesth Analg 1999; 88: 1051-2.

Lancaster P, Chadwick M. Liver trauma secondary to ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block. Br J Anaesth 2010; 104: 509-10.

Long JB, Birmingham PK, De Oliveira GS, Jr Schaldenbrand KM, Suresh S. Transversus abdominis plane block in children: a multicenter safety analysis of 1994 cases from the PRAN (Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network) database. Anesth Analg 2014; 119: 395-9.

Parvaiz MA, Korwar V, McArthur D, Claxton A, Dyer J, Isgar B. Large retroperitoneal haematoma: an unexpected complication of ilioinguinal nerve block for inguinal hernia repair. Anaesthesia 2012; 67: 80-1.

Shirozu K, Kuramoto S, Kido S, Hayamizu K, Karashima Y, Hoka S. Hematoma after transversus abdominis plane block in a patient with HELLP syndrome: a case report. A A Case Rep 2017; 8: 257-60.

Ueshima H. Pneumothorax after the erector spinae plane block. J Clin Anesth 2018; 48: 12.

Ueshima H, Otake H. Ultrasound-guided pectoral nerves (PECS) block: complications observed in 498 consecutive cases. J Clin Anesth 2017; 42: 46.

Vaisman J. Pelvic hematoma after an ilioinguinal nerve block for orchialgia. Anesth Analg 2001; 92: 1048-9.

Yuen PM, Ng PS. Retroperitoneal hematoma after a rectus sheath block. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2004; 11: 448.

Dolan J, Lucie P, Geary T, Smith M, Kenny GN. The rectus sheath block: accuracy of local anesthetic placement by trainee anesthesiologists using loss of resistance or ultrasound guidance. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2009; 34: 247-50.

Farooq M, Carey M. A case of liver trauma with a blunt regional anesthesia needle while performing transversus abdominis plane block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2008; 33: 274-5.

Manatakis DK, Stamos N, Agalianos C, Karvelis MA, Gkiaourakis M, Davides D. Transient femoral nerve palsy complicating “blind” transversus abdominis plane block. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2013; 2013: 874215.

Lee S, Goetz T, Gharapetian A. Unanticipated motor weakness with ultrasound-guided transversalis fascia plane block. A A Case Rep 2015; 5: 124-5.

Salaria ON, Kannan M, Kerner B, Goldman H. A rare complication of a TAP block performed after caesarean delivery. Case Rep Anesthesiol 2017; 2017: 1072576.

Melvin JP, Schrot RJ, Chu GM, Chin KJ. Low thoracic erector spinae plane block for perioperative analgesia in lumbosacral spine surgery: a case series. Can J Anesth 2018; 65: 1057-65.

Sondekoppam RV, Ip V, Johnston DF, et al. Ultrasound-guided lateral-medial transmuscular quadratus lumborum block for analgesia following anterior iliac crest bone graft harvesting: a clinical and anatomical study. Can J Anesth 2018; 65: 178-87.

Visoiu M, Pan S. Quadratus lumborum blocks: two cases of associated hematoma. Paediatr Anaesth 2019; . https://doi.org/10.1111/pan.13588.

Pace MM, Sharma B, Anderson-Dam J, Fleischmann K, Warren L, Stefanovich P. Ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral blockade: a retrospective study of the incidence of complications. Anesth Analg 2016; 122: 1186-91.

Kelly ME, Mc Nicholas D, Killen J, Coyne J, Sweeney KJ, McDonnell J. Thoracic paravertebral blockade in breast surgery: is pneumothorax an appreciable concern? A review of over 1000 cases. Breast J 2018; 24: 23-7.

Anderson-Dam J, Stefanovich P, Warren L, Fleischmann K, Sunder N. Review of single-center experience with 466 preoperative transverse, in-plane, ultrasound-guided thoracic paravertebral blocks for postoperative pain control for mastectomy with immediate reconstruction. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012; A57 (abstract).

Naja Z, Lonnqvist PA. Somatic paravertebral nerve blockade. Incidence of failed block and complications. Anaesthesia 2001; 56: 1184-8.

Visoiu M, Cassara A, Yang CI. Bilateral paravertebral blockade (T7-10) versus incisional local anesthetic administration for pediatric laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized clinical study. Anesth Analg 2015; 120: 1106-13.

Lonnqvist PA, MacKenzie J, Soni AK, Conacher ID. Paravertebral blockade. Failure rate and complications. Anaesthesia 1995; 50: 813-5.

Berta E, Spanhel J, Smakal O, Smolka V, Gabrhelik T, Lonngvist PA. Single injection paravertebral block for renal surgery in children. Paediatr Anaesth 2008; 18: 593-7.

Cantó M, Sánchez MJ, Casas MA, Bataller ML. Bilateral paravertebral blockade for conventional cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia 2003; 58: 365-70.

Gieri B, Conrad E, Alarcon L, Chelly J. Safety associated with the removal of paravertebral catheters in trauma patients receiving enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011; A602 (abstract).

Sopena-Zubiria LA, Fernandez-Mere LA, Munoz Gonzalez F, Valdes Arias C. Multiple-injection thoracic paravertebral block for reconstructive breast surgery (Spanish). Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 2010; 57: 357-63.

Borle AP, Chhabra A, Subramaniam R, et al. Analgesic efficacy of paravertebral bupivacaine during percutaneous nephrolithotomy: an observer blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Endourol 2014; 28: 1085-90.

Berta E, Spanhel J, Smakal O, Gabrhelik T. Single-shot paravertebral block in children - the initial experience. Anesteziol a Intenziv Med 2007; 18: 216-20.

Patnaik R, Chhabra A, Subramaniam R, et al. Comparison of paravertebral block by anatomic landmark technique to ultrasound-guided paravertebral block for breast surgery anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2018; 43: 385-90.

Fallatah S, Mousa W. Multiple levels paravertebral block versus morphine patient-controlled analgesia for postoperative analgesia following breast cancer surgery with unilateral lumpectomy, and axillary lymph nodes dissection. Saudi J Anaesth 2016; 10: 13-7.

Chalam K, Patnaik SS, Sunil C, Bansal T. Comparative study of ultrasound-guided paravertebral block with ropivacaine versus bupivacaine for post-operative pain relief in children undergoing thoracotomy for patent ductus arteriosus ligation surgery. Indian J Anaesth 2015; 59: 493-8.

Moawad HE, Mousa SA, El-Hefnawy AS. Single-dose paravertebral blockade versus epidural blockade for pain relief after open renal surgery: a prospective randomized study. Saudi J Anaesth 2013; 7: 61-7.

Sanchez F, Esturi R, Galbis J, Estors M, Llopis JE. Ultrasound-guided continuous paravertebral block in thoracic surgery: description of a new technique. Br J Anaesth 2012; 108: 415-6 (abstract).

Adriani J, Evangelou M. Complications of regional anesthesia. Curr Res Anesth Analg 1955; 34: 96-101.

Okitsu K, Iritakenishi T, Iwasaki M, Imada T, Fujino Y. Risk of hematoma in patients with a bleeding risk undergoing cardiovascular surgery with a paravertebral catheter. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017; 31: 453-7.