Abstract

Background

Culinary nutrition education programs are increasingly used as a public health intervention for older adults. These programs often integrate nutrition education in addition to interactive cooking workshops or displays to create programs suitable for older adults’ needs, ability and behaviour change. Synthesising the existing literature on nutrition education and interactive cooking programs for older adults is important to guide future program development to support healthy ageing.

Objectives

To determine the extent of published literature and report the characteristics and outcomes of interactive culinary nutrition education programs for older adults (> 51 years).

Design

This scoping review followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines recommended for reporting and conducting a scoping review.

Methods

Five databases were searched of relevant papers published to May 2022 using a structured search strategy. Inclusion criteria included: older adults (≥ 51 years), intervention had both an interactive culinary element and nutrition education and reported dietary outcome. Titles and abstracts were screened by two reviewers, followed by full-text retrieval. Data were charted regarding the characteristics of the program and outcomes assessed.

Results

A total of 39 articles met the full inclusion criteria. The majority of these studies (n= 23) were inclusive of a range of age groups where older adults were the majority but did not target older adults exclusively. There were large variations in the design of the programs such as the number of classes (1 to 20), duration of programs (2 weeks to 2 years), session topics, and whether a theoretical model was used or not and which model. All programs were face-to-face (n= 39) with only two programs including alternatives or additional delivery approaches beside face-to-face settings. The most common outcomes assessed were dietary behaviour, dietary intake and anthropometrics.

Conclusion

Culinary nutrition education programs provide an environment to improve dietary habits and health literacy of older adults. However, our review found that only a small number of programs were intentionally designed for older adults. This review provides a summary to inform researchers and policy makers on current culinary nutrition education programs for older adults. It also recommends providing face-to-face alternatives that will be accessible to a wider group of older adults with fewer restrictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poor nutrition is a key contributor to the global burden of disease (1). It increases the risk of developing non-communicable diseases and mortality (1). A high-quality diet that is characterised by variety and that is high in vegetables, fruits and whole grains is well recognised to improve quality of life, better manage chronic diseases and to reduce mortality (2, 3). While nutrition is important at all ages, it is of particular importance for older adults (aged ≥ 65 years) and is fundamental to promoting functional ability that enables wellbeing in older age (4).

A number of physiological, psychosocial, and personal factors play key roles in older adults’ food choices (5). Age-related physiological changes can include changes in appetite, taste and smell, oral health and the efficiency of chewing (5, 6). A large and growing body of literature has reported an established connection between these physiological changes and sub-optimal nutritional intake in older adults (7). Changes in taste and smell affect food intake by reducing the enjoyment of eating and appetite, which in turn can affect portion sizes and food choices (6, 8). The loss of taste can lead to higher consumption of food high in salt and sugar to increase meal palatability (5, 6). In addition, poor dentition and compromised chewing tends to increase with age, and this may result in changes to food choices (5), for example, reducing the intake of certain foods that are crunchy, dry, solid and harder to chew such as nuts, fruit, vegetables and meats.

Psychosocial factors such as living alone, and bereavement and grief following the loss of a partner have also been reported to affect older people’s food intake. The number of older adults who live alone is about 28% in the United States, while in Australia, approximately about 25% of people aged 65 and over live alone (9). Living alone is associated with low motivation for older adults to shop, prepare and eat meals. Research suggests that people living alone eat less diverse food and lacks some core food groups such as fish, fruit and vegetables compared to people not living alone (10). They also skip meals or replace them with snacks (11, 12). This can occur as a result of losing pleasure while eating without companionship, which appears to affect women more than men (11, 13). Furthermore, personal factors such as nutrition knowledge, cooking skills and income affect food intake (14). Food budget directly impacts food choice and may lead to poor dietary intake, which may decrease with age and retirement (15). Cooking skills in older people varies based on education level and gender with women having a higher level of cooking skills than men in many populations (12, 16–18). While having good cooking skills does not necessarily ensure that older people meet their energy requirement, people with better cooking skills have shown to have a healthier diet intake compared with older people with lower level skills (12, 18)

Nutrition education programs and culinary classes are increasingly used as a public health intervention (19, 20). Combining nutrition education and culinary classes in a program helps individuals to gain understanding on how to replicate healthy meals and focus on healthy nutrition patterns (19). This integration allows participants to actively engage in the program, enhancing autonomy, empowerment, and behaviour modification (21). These are often referred to in the literature as culinary nutrition (22). The level of education and amount of cooking within existing programs is highly variable and can include nutrition information, group-based hands-on activities such as food demonstrations and taste-testing, as well as discussions on lifestyle topics such as meal planning, food safety and a supermarket tour (23). Integrating a hands-on cooking experience is important to provide cooking literacy and has shown to increase the consumption of fruit and vegetables (24). Depending on the style of program delivery and if the program is group-based these programs allow participants to meet new people and expand their social networks (21). Programs based on behavioural theory are more likely to achieve the desired change as they focus on activities that help individuals to reflect upon their risk behaviours and help change them to healthier habits, specifically addressing barriers and facilitators to eating (21, 25). Various theoretical frameworks have been used in the design of interventions based on the health problem, intervention goals, and practices (26). The most common theory applied to cooking programs is the social cognitive theory (27).

Research has been published to describe either nutrition education programs (20) or culinary education programs in children, women during childbearing years or adults (19, 28, 29). However, no review has described programs that combined these two modules together and in older adults. Existing culinary nutrition education programs are varied, with some specifically designed for older adults exclusively while others include older adults in their broader population. This scoping review synthesises the existing literature of culinary nutrition education programs for older adults aimed at improving the health and wellbeing of community-dwelling older adults in terms of the number, characteristics, strategies, delivery approach and theoretical framework used in these programs. This scoping review’s findings will help shape decisions regarding future evidence-based program development by identifying components of culinary nutrition education programs for older adults associated with success. This scoping review will answer the following questions: (1) What are the characteristics of culinary nutrition education programs for older adults? (2) What are the measured outcomes of culinary nutrition education interventions for older adults?

Research design and Methods

This scoping review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines and a study protocol (supplementary appendix A) that was developed prior to conducting the search (30).

Literature search

Five databases (MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), CINAHL, Scopus and Cochrane Library) were searched in May 2022 for all previous entries with no date limits. Keywords included “Cooking/or cook*,” “culinary or eating or dietary,” “taste test* or food sampl*,” “((cooking or food or recipe* or meal*) adj3 demonstrat*),” “((“meal* or food) adj3 (budget* or plan* or skill* or knowledge or education* or prepar* or literac* or shop*)), AND “nutrition* adj5 (intervention* or program* or workshop or workshops or knowledge or education)),” AND “aged/,” “((aged or elderly or older or senior) adj3 (male* or female* or men or women or citizen* or person or people or population))”. The search strategy was pilot tested and further refined with the assistance of a senior librarian before the final search was conducted.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible if they included older adults (≥ 51 years) and the intervention had both an interactive cooking element and nutrition education. Studies that were not exclusively for older people, but where some participants were aged ≥ 51 years were also included if the results were reported and stratified by age. This strategy was employed to provide a comprehensive synthesis of all culinary nutrition education programs whether they were specifically designed for older adults or for people of any age. An interactive cooking element was defined as any of the following: the cooking of meals, recipe demonstration, taste testing or food sampling. Participants needed to be living independently and be preparing their own meals. Studies were included regardless of comparator used, or methodological approach. Qualitative studies were included. Studies needed to report dietary outcomes which included but was not limited to food intake and dietary behaviours and be written in English. Studies were excluded if they did not combine nutrition education and interactive cooking activities (i.e. reported either one of these elements individually), were not in older adults (<51 years) or results were not stratified by age, did not measure dietary outcomes (e.g., measured physiological outcomes or presented an evaluation of program content only), not an original paper (e.g., review articles, commentaries, reports), if full text was not available (e.g., conference abstract), or if they were in a language other than English.

Screening

Studies were screened by two independent reviewers (MA and BB). Title and abstracts were first screened using Covidence (systematic review software). Remaining full text studies were extracted and screened for inclusion. A third reviewer (CC or TB) resolved any disagreements.

Data extraction

Data extracted included study details (including study design, program activities, class frequency and duration, education topics), participant characteristics, program characteristics, and program outcome measures (including dietary intake, anthropometric measurements, health measures, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours). Data were synthesised descriptively to report characteristics of the program and outcomes. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer (MA) and validated by another (BB, TB or CC), with any discrepancies resolved through consensus. Dietary outcomes were categorised into major groupings such as overall food intake based, dietary behaviours, malnutrition, fruit and vegetables and nutrient/food based, all other variables were considered non dietary outcomes. As this was a scoping review, no quality appraisal was performed for this study.

Results

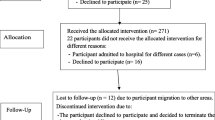

In total, 7937 articles were identified by the search. After removing duplicates, 4670 were eligible for title and abstract screening. Of these, 364 were eligible for full-text screening and 39 articles met the inclusion criteria of this review (Figure 1). The major reasons for exclusion were; wrong population (<50 years) (n=151), wrong intervention (did not combine nutrition education and interactive cooking activities but reported either one of these elements individually) (n=101), or wrong study design (i.e. report, review articles, conference abstracts) (n=61).

Overall characteristics of nutrition and cooking programs

Studies were conducted in 14 countries with the majority in the United States (n=24) (31–53) followed by Brazil (n=2). The majority (n=29) of the articles were published between 2011 and 2021 (32, 34–36, 38, 40–46, 49–51, 53–66). Study designs were primarily pre-post studies (n=20) (33–35, 38–40, 43, 44, 47–51, 55–57, 59, 60, 65, 67), followed by randomised control trial (n=15) (37, 41, 42, 45, 46, 52, 53, 58, 61–64, 66, 68, 69) and quasi-experimental studies (n=4) (31, 32, 36, 54). Program duration ranged from 2 weeks to 2 years, and the number of classes ranged from 1 to 20 classes (Table 1). A majority of the educators were reported to be a dietitian and/or nutritionist (n=17) (31, 32, 35, 42, 43, 47–51, 55, 57, 61–63, 67, 69), a registered nurse and/or trained educator (n=10) (33, 34, 37, 44, 45, 52, 53, 58, 60, 64). Thirteen studies did not report the qualifications of the class instructor (36, 38–41, 46, 54, 56, 58, 59, 65, 66, 68).

Program Participants

This review identified 16 culinary nutrition education programs that were specifically designed for older adults aged ≥ 51 years (35, 36, 39, 40, 51, 54–56, 58–60, 64, 66, 67, 69) and 23 that were not specifically designed for older adults but included them in a broader population group (31–34, 37, 38, 41–50, 52, 53, 57, 61–63, 65, 68). Sample size ranged from 8 to 2519 participants, with the majority having less than 100 participants. Of the 39 studies, 10 studies targeted and included women only (33, 42, 43, 46, 50, 52, 53, 56, 61, 68) and the remaining 29 included men and women (Table 1). Some studies recruited participants from the general public (n=13) (35, 36, 40, 51, 54–56, 59, 60, 64, 65, 67, 69), while other studies targeted people with a specific health condition as follows; diabetes or pre-diabetes (n=8) (31, 32, 34, 38, 45, 47, 61, 62), hypertension/prehypertension (n=2) (35, 58), high cardiometabolic risk or undergoing cardiac rehabilitation (n=2) (48, 57), obesity (n=2) (35, 53), mild cognitive impairment (n=1) (66), chronic kidney disease (n=1) (63), and metabolic syndrome (n=1) (49). Remaining studies targeted breast cancer survivors (n=4) (42, 43, 50, 53), post-menopausal women (n=1) (68), low income earners (n=1) (41, 43), and specific ethnic groups in the US (n=8) such as Hispanic (42), Black (39), Latinas (46), and African Americans (31, 33, 37, 44, 52) (Table 2).

Program curriculum

Nutrition education content varied based on program aims and target population (Table 2). Some programs focused on disease management and provided specific dietary instructions to better manage diseases. Examples of this included reduction of salt intake in people with hypertension, management of low protein intake in people with chronic kidney diseases and increasing of calcium intake in postmenopausal women. Overall, the majority of programs (n=36) were reported as promoting healthy eating as per the relevant national health guidelines. With regards to specific diets, the Mediterranean diet was promoted in three different programs including one in a Mediterranean population (57), one for people with diabetes (57) and one for breast cancer survivors (53). Some programs reported the use of printed materials (n=18) (34, 36, 37, 40–43, 51–54, 59, 60, 63, 64, 66–68). Only a small number (n=6) used videos in the programs’ activities (31, 34, 41, 47, 55, 68). All programs were delivered face-to-face and only one program used both face-to-face and an online-telehealth approach (38).

Integrative cooking component

The integrative cooking component highly varied across the studies. However, the most common activities were taste testing (n=19) (31–33, 36, 37, 40, 41, 44, 46–48, 52–55, 59, 62, 63, 69), viewing a cooking demonstration (n=13) (32, 39, 41, 43, 46, 50–53, 57, 60, 66, 67), the act of cooking (n= 11) (31, 32, 35, 42, 44, 45, 49, 57, 64, 65, 68), and sharing the meal or eating (n=5) (36, 42, 49, 64, 65). Few programs reported using videos (n=6) (31, 34, 41, 47, 55, 68) or visual aids like PowerPoint slides or posters (n=7) (34, 46, 48, 53, 59, 68) to deliver information. Only two programs had an online component to provide additional information for participants (32, 35).

Theoretical framework

Of the 39 included articles, 18 studies used a behavioural theory to guide the development and implementation of program activities (31, 32, 34, 37, 40–42, 46, 49, 52, 54, 58–62, 64, 65). Theories underpinning programs varied, with some combining elements from two theories. The most commonly used theory was Social Cognitive Theory (n=8) followed by Self-Efficacy Theory (n=3) and Social Marketing Theory (n=2) (Table S1).

Stakeholder engagement

Ten programs reported meeting with stakeholders, who were primarily end-users such as older adults, to determine their needs before designing the program (31, 33, 40, 41, 43, 52, 55, 59, 62, 67). 4 of 10 programs were targeting older adults (Table 1). The most common method of engagement was via focus groups.

Programs outcomes

Dietary outcomes

There were five categories of reported dietary outcomes; (i) Dietary behaviours (n=12) (31, 34, 35, 38, 41, 45, 46, 48, 51, 57, 60, 65), (ii) Overall dietary intake (n=12) (32, 38–40, 42, 44, 47, 52, 56, 61, 62, 66), (iii) Fruit and vegetable intake (n=6) (33, 36, 37, 41, 43, 50), (iv) Malnutrition (n=6) (40, 51, 54, 55, 64, 67) and (v) other specific nutrient/food based outcome such as protein (63), calcium (68), salt (58), whole grain (59), adherence to the Mediterranean diet (53), and functional food (48). Malnutrition was measured only in the programs that specifically targeted older adults (n=6). The most common assessment tools were 3-day food records (n=5) and 24-hour food recall (n=4). Most programs (n=32) showed improvement in the dietary outcomes assessed, however 6 reported no change.

Non-dietary outcomes

Non-dietary outcomes varied widely and included behavioural measures such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, practice, self-efficacy and physiological measures such as lipid profile, blood pressure, physical activity, and cognitive status. The most common non-dietary assessments used included anthropometric measures (n=15), knowledge (n=12) for example knowledge about whole grain and diabetes treatment regimen, and blood markers, with the most common biomarker collected being Triglycerides (n=9).

Further details on study outcomes are presented in Table S2.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to synthesise existing published literature in relation to culinary nutrition education programs that are aimed at improving the health and wellbeing of community-dwelling older adults. A total of 39 studies were identified and included in the review.

Of the included programs, 15 did not specifically target older adults and there were large variations in the reported culinary nutrition education programs. Examples of variations included the number, frequency and duration of sessions, session topics, group sizes, interactive format (i.e. viewing recipe demonstration or tasting food), providing companionship and sharing meals. Most programs measured outcomes pre-and post-program. Longer term outcomes at 2- or 3-years post-program were only reported by few studies (49, 52, 67).

Programs based on a behaviour change theory showed positive changes in dietary outcomes. This aligns with previous findings in the literature that showed favourable behaviour change using a theoretical framework to design health promotion programs (21, 25). Furthermore, findings showed that some study teams engaged with end-users as co-researchers, either through the conducting of focus groups with end users prior the program, and/or conducting of continuous evaluation during program to identify and ensure programs met their population needs. For example, the Evergreen Action program had an older adults’ advisory group, who reported that in their particular population, older men faced difficulties with cooking. In response to feedback, the team designed additional workshops focused on men called “Men can Cook” (67). These workshops helped participants to improve their confidence in cooking and finding healthy food alternatives (70). Engaging stakeholders and end-users in the design of programs can play a significant role in its effectiveness. Culinary nutrition education and cooking classes are more likely to succeed if they first identify participant needs and involve them in the design process (25, 71), as this ensures the program is relevant and beneficial for the stakeholders (72).

Programs tended to focus on country-specific dietary guidelines for older adults. Despite the Mediterranean diet being promoted for specific disease populations, there were no interventions that promoted one specific dietary approach over another for the general older population. Surprisingly, most programs were face-to-face only and did not offer online components or delivery except three programs (32, 35, 38). The program that used telehealth classes in some sites showed that there were no significant differences in outcomes between the face-to-face and telehealth delivery modes. Online and telehealth programs can be effective in older adults to promote health and can be beneficial for delivery with impacts such as covid (73–75). Given many programs encouraged eating a meal together, this may be why programs tended to be face-to-face. With telehealth or online technologies consuming a meal may still be achieved however has not yet been tested and explored as would also require use of technology and owning of devices which may be more limited in older adults than when compared with younger population groups (76). However, studies on older adults during COVID have shown that older adults are online, and they found online programs helpful (75). Online culinary nutrition programs will show recipes demonstrations and reach older adults who would not usually go to these programs due to some limitations and could include a virtual socialising group. Future programs might consider remote delivery or going online after the spread of global pandemic COVID-19. Reported studies were conducted before COVID-19.

Although visual aids (e.g. videos, handouts) are widely available and commonly used tools to deliver cooking demonstrations, few studies reported using them or reporting their use. Whole Grain nutrition education program provided some evidence on the benefit of using visuals to maintain active engagement with content. This program had two delivery modes, PowerPoints slides (sites=13) and non-PowerPoint slides (sites=12), reported that while all participants showed improvement in knowledge acquisition, participants who joined PowerPoint-based classes had significantly higher knowledge scores than participants in the non-PowerPoint-based classes (59). The decision to use the PowerPoint slides was based on older adults’ preference from a needs assessment conducted before designing the program. All participants from both delivery modes showed a significant increase in frequencies of eating whole-grain foods. Collectively visual aids help to reinforce health information especially in people with low literacy, leading to better comprehension, adherence, and outcomes (77).

This review identified the absence of online programs that offer flexibility compared to face-to-face programs. Reported face-to-face programs were limited by class size, specific geographic location, time, and inclusion criteria such as ethnicity or church membership. These limitations may have existed for a variety of reasons such as limited resources, limited budget, and cost of foods. Online programs, on the other hand, reach a larger number of participants with lower cost. They can provide an opportunity for participation for vulnerable older adults and others who might be restricted from attending face-to-face programs due to location, transportation restrictions or health status. Online programs also can provide unlimited access to evidence-based content giving older adults a reliable and practical source of information. Access to evidence-based content is especially important as research has shown that many older adults were confused by changing and mixed messages in public nutrition campaigns which made them question the credibility of food messages (78). Our findings show a need to develop online culinary nutrition education programs targeting older adults considering the COVID-19 pandemic. Such a program will provide a nutrition knowledge base for preparing meals at home and maintaining healthy eating patterns. This scoping review can inform researchers and identify implications for practice to maintain health for older adults.

Although this study provided an in-depth review of the literature on culinary nutrition education programs for older adults, this study has some limitations. It only included papers that were published in peer-reviewed journals, and was limited to English language, excluding any articles that may be relevant that do not meet these specific criteria. As this was a scoping review, a quality assessment of included papers was not conducted, so no evaluation on the quality of the included articles can be made. Information about the programs was inconsistently reported; this was a particular issue in regard to the structure of education topics included in the programs.

Strengths of this review include an extensive search conducted in five electronic bibliographic databases, ensuring a broad search of the literature. Search terms included were comprehensive, and there was no time limit applied capturing programs available in the literature.

Conclusion

Culinary nutrition education programs may provide an optimal environment to improve the dietary habits and health of older adults. Despite this, very few programs have intentionally designed for older adults. This review provides a summary to inform researchers and policy makers on current culinary nutrition programs for older adults. Further research assessing the quality and effectiveness of cooking and nutrition programs is needed. In the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, it appears that very few online-only programs exist, indicating a need for new online programs to be designed for older adults.

References

Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, Hanson SW, Chatterji S, Vos T. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2021;396(10267):2006–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32340-0.

Neuhouser ML. The importance of healthy dietary patterns in chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res. 2019;70:3–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2018.06.002.

Cena H, Calder PC. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):334. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020334.

Shlisky J, Bloom DE, Beaudreault AR, Tucker KL, Keller HH, Freund-Levi Y, et al. Nutritional considerations for healthy aging and reduction in age-related chronic disease. Advances in nutrition. 2017;8(1):17. doi: https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.013474.

Host A, McMahon A-T, Walton K, Charlton K. Factors influencing food choice for independently living older people—a systematic literature review. Journal of nutrition in gerontology and geriatrics. 2016;35(2):67–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2016.1168760.

Whitelock E, Ensaff H. On your own: older adults’ food choice and dietary habits. Nutrients. 2018;10(4):413. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040413.

Toniazzo MP, Amorim PdSA, Muniz FWMG, Weidlich P. Relationship of nutritional status and oral health in elderly: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Clinical nutrition. 2018;37(3):824–30. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2017.03.014.

Holmes B, Roberts C. Diet quality and the influence of social and physical factors on food consumption and nutrient intake in materially deprived older people. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2011;65(4):538–45. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2010.293.

Australian Institute of Health Welfare (2021) Older Australians. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/older-people/older-australians.

Hanna KL, Collins PF. Relationship between living alone and food and nutrient intake. Nutrition reviews. 2015;73(9):594–611. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv024

Wang X, Shen W, Wang C, Zhang X, Xiao Y, He F, et al. Association between eating alone and depressive symptom in elders: a cross-sectional study. BMC geriatrics. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0197-2.

Hughes G, Bennett KM, Hetherington MM. Old and alone: barriers to healthy eating in older men living on their own. Appetite. 2004;43(3):269–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2004.06.002.

Tiedt AD. The gender gap in depressive symptoms among Japanese elders: evaluating social support and health as mediating factors. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology. 2010;25(3):239–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-010-9122-x.

Dean M, Raats MM, Grunert KG, Lumbers M. Factors influencing eating a varied diet in old age. Public health nutrition. 2009;12(12):2421–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980009005448.

Sawyer ADM, van Lenthe F, Kamphuis CBM, Terragni L, Roos G, Poelman MP, et al. Dynamics of the complex food environment underlying dietary intake in low-income groups: a systems map of associations extracted from a systematic umbrella literature review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2021;18(1):96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01164-1.

Tani Y, Fujiwara T, Kondo K. Cooking skills related to potential benefits for dietary behaviors and weight status among older Japanese men and women: a cross-sectional study from the JAGES. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2020;17(1):1–12. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00986-9.

McGowan L, Pot GK, Stephen AM, Lavelle F, Spence M, Raats M, et al. The influence of socio-demographic, psychological and knowledge-related variables alongside perceived cooking and food skills abilities in the prediction of diet quality in adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2016;13(1):1–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0440-4.

Hartmann C, Dohle S, Siegrist M. Importance of cooking skills for balanced food choices. Appetite. 2013;65:125–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.01.016.

Hasan B, Thompson WG, Almasri J, Wang Z, Lakis S, Prokop LJ, et al. The effect of culinary interventions (cooking classes) on dietary intake and behavioral change: a systematic review and evidence map. BMC Nutrition. 2019;5(1):29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-019-0293-8.

Bandayrel K, Wong S. Systematic Literature Review of Randomized Control Trials Assessing the Effectiveness of Nutrition Interventions in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2011;43(4):251–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2010.01.004.

Lyons BP. Nutrition education intervention with community-dwelling older adults: research challenges and opportunities. Journal of community health. 2014;39(4):810–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-013-9810-x.

Kerrison DA, Condrasky MD, Sharp JL. Culinary nutrition education for undergraduate nutrition dietetics students. British Food Journal. 2017. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/bfj-09-2016-0437.

Rees R, Hinds K, Dickson K, O’Mara-Eves A, Thomas J. Communities that cook: A systematic review of the effectiveness and appropriateness of interventions to introduce adults to home cooking: Executive summary. Journal of the Home Economics Institute of Australia. 2012;19(3):31–2.

McGowan L, Caraher M, Raats M, Lavelle F, Hollywood L, McDowell D, et al. Domestic cooking and food skills: a review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2017;57(11):2412–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2015.1072495.

Juckett LA, Lee K, Bunger AC, Brostow DP. Implementing Nutrition Education Programs in Congregate Dining Service Settings: A Scoping Review. The Gerontologist. 2020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa109.

Sussman SY. Handbook of program development for health behavior research and practice. Sage; 2001. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412991445.

Reicks M, Trofholz AC, Stang JS, Laska MN. Impact of cooking and home food preparation interventions among adults: outcomes and implications for future programs. Journal of nutrition education and behavior. 2014;46(4):259–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.02.001.

Muzaffar H, Metcalfe JJ, Fiese B. Narrative review of culinary interventions with children in schools to promote healthy eating: directions for future research and practice. Current developments in nutrition. 2018;2(6):nzy016. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/cdn/nzy016.

Taylor RM, Wolfson JA, Lavelle F, Dean M, Frawley J, Hutchesson MJ, et al. Impact of preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum culinary nutrition education interventions: a systematic review. Nutrition reviews. 2021;79(11):1186–203. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa124.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of internal medicine. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850.

Anderson-Loftin W, Barnett S, Sullivan P, Bunn PS, Tavakoli A. Culturally competent dietary education for southern rural African Americans with diabetes...including commentary by Melkus GD. Diabetes Educator. 2002;28(2):245–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/014572170202800210.

Archuleta M, Vanleeuwen D, Halderson K, Jackson K, Bock MA, Eastman W, et al. Cooking schools improve nutrient intake patterns of people with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior. 2012;44(4):319–25. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2011.10.006.

Barnhart JM, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Nelson M, Raiford Y, Wylie-Rosett J. An innovative, culturally-sensitive dietary intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake among African-American women: a pilot study. Topics in Clinical Nutrition. 1998;13(2):63–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00008486-199803000-00007.

Bielamowicz MK, Pope P, Rice CA. Sustaining a creative community-based diabetes education program: motivating Texans with type 2 diabetes to do well with diabetes control. The Diabetes Educator. 2013;39(1):119–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721712470605.

Black M, LaCroix R, Hoerster K, Chen S, Ritchey K, Souza M, et al. Healthy teaching kitchen programs: experiential nutrition education across Veterans Health Administration, 2018. American Journal of Public Health. 2019;109(12):1718–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2019.305358.

Brewer D, Dickens E, Humphrey A, Stephenson T. Increased fruit and vegetable intake among older adults participating in Kentucky’s congregate meal site program. Educational gerontology. 2016;42(11):771–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2016.1231511.

Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, Kalsbeek WD, Dodds J, Cowan A, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. American journal of public health. 1999;89(9):1390–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1390.

Dexter AS, Pope JF, Erickson D, Fontenot C, Ollendike E, Walker E. Cooking education improves cooking confidence and dietary habits in veterans. The Diabetes Educator. 2019;45(4):442–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721719848429.

Doshi NJ, Hurley RS, Garrison ME, Stombaugh IS, Rebovich EJ, Wodarski LA, et al. Effectiveness of a nutrition education and physical fitness training program in lowering lipid levels in the black elderly. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 1994;13(3):23–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/j052v13n03_02.

Francis SL, MacNab L, Shelley M. A theory-based newsletter nutrition education program reduces nutritional risk and improves dietary intake for congregate meal participants. Journal of nutrition in gerontology and geriatrics. 2014;33(2):91–107. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2014.906336.

Gans KM, Risica PM, Keita AD, Dionne L, Mello J, Stowers KC, et al. Multilevel approaches to increase fruit and vegetable intake in low-income housing communities: final results of the ‘Live Well, Viva Bien’cluster-randomized trial. International journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity. 2018;15(1):1–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0704-2.

Greenlee H, Gaffney AO, Aycinena AC, Koch P, Contento I, Karmally W, et al. ¡Cocinar Para Su Salud!: Randomized Controlled Trial of a Culturally Based Dietary Intervention among Hispanic Breast Cancer Survivors. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics. 2015;115(5 Suppl):S42–S56.e3. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.02.027.

Griffith KA, Royak-Schaler R, Nesbitt K, Zhan M, Kozlovsky A, Hurley K, et al. A culturally specific dietary plan to manage weight gain among African American breast cancer survivors: a feasibility study. Nutrition and health. 2012;21(2):97–105. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0260106012459938.

Kennedy BM, Ryan DH, Johnson WD, Harsha DW, Newton Jr RL, Champagne CM, et al. Baton rouge healthy eating and lifestyle program (BR-HELP): a pilot health promotion program. Journal of prevention & intervention in the community. 2015;43(2):95–108. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2014.973256.

Monlezun DJ, Kasprowicz E, Tosh KW, Nix J, Urday P, Tice D, et al. Medical school-based teaching kitchen improves HbA1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol for patients with type 2 diabetes: results from a novel randomized controlled trial. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2015;109(2):420–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2015.05.007.

Otilingam PG, Gatz M, Tello E, Escobar AJ, Goldstein A, Torres M, et al. Buenos habitos alimenticios para una buena salud: evaluation of a nutrition education program to improve heart health and brain health in Latinas. Journal of aging and health. 2015;27(1):177–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314549660.

Pedersen AL, Lowry KR. A regional diabetes nutrition education program: its effect on knowledge and eating behavior. The Diabetes Educator. 1992;18(5):416–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/014572179201800509.

Pelletier S, Kundrat S, Hasler CM. Effects of a functional foods nutrition education program with cardiac rehabilitation patients. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2003;23(5):334–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00008483-200309000-00002.

Powell LH, Appelhans BM, Ventrelle J, Karavolos K, March ML, Ong JC, et al. Development of a lifestyle intervention for the metabolic syndrome: Discovery through proof-of-concept. Health Psychology. 2018;37(10):929. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000665.

Schneeberger D, Golubic M, Moore HC, Weiss K, Abraham J, Montero A, et al. Lifestyle medicine-focused shared medical appointments to improve risk factors for chronic diseases and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2019;25(1):40–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0154.

Wunderlich S, Bai Y, Piemonte J. Nutrition risk factors among home delivered and congregate meal participants: need for enhancement of nutrition education and counseling among home delivered meal participants. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2011;15(9):768–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-011-0090-9.

Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Reports. 2001;116(1):68–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/phr/116.s1.68.

Zuniga KE, Parma DL, Muñoz E, Spaniol M, Wargovich M, Ramirez AG. Dietary intervention among breast cancer survivors increased adherence to a Mediterranean-style, anti-inflammatory dietary pattern: The Rx for Better Breast Health Randomized Controlled Trial. Breast cancer research and treatment. 2019;173(1):145–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-018-4982-9.

Chen SH, Huang YP, Shao JH. Effects of a dietary self-management programme for community-dwelling older adults: a quasi-experimental design. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2017;31(3):619–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12375.

Chung LM, Chung JW. Effectiveness of a food education program in improving appetite and nutritional status of elderly adults living at home. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014;23(2):315–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.2.18.

Friedrich M, Goluch-Koniuszy Z. The effectiveness of nutritional education among women aged 60–85 on the basis of anthropometric parameters and lipid profiles. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny. 2017;68(3).

Grimaldi M, Ciano O, Manzo M, Rispoli M, Guglielmi M, Limardi A, et al. Intensive dietary intervention promoting the Mediterranean diet in people with high cardiometabolic risk: a non-randomized study. Acta Diabetologica. 2018;55(3):219–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-017-1078-7.

Irwan AM, Kato M, Kitaoka K, Ueno E, Tsujiguchi H, Shogenji M. Development of the salt-reduction and efficacy-maintenance program in Indonesia. Nursing & health sciences. 2016;18(4):519–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12305.

MacNab LR, Davis K, Francis SL, Violette C. Whole grain nutrition education program improves whole grain knowledge and behaviors among community-residing older adults. Journal of Nutrition in Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2017;36(4):189–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21551197.2017.1384424.

Meethien N, Pothiban L, Ostwald SK, Sucamvang K, Panuthai S. Effectiveness of nutritional education in promoting healthy eating among elders in northeastern Thailand. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research. 2011;15(3):188–201.

Menezes MC, Mingoti SA, Cardoso CS, Mendonca Rde D, Lopes AC. Intervention based on Transtheoretical Model promotes anthropometric and nutritional improvements — a randomized controlled trial. Eating Behaviors. 2015;17:37–44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.007.

Muchiri JW, Gericke GJ, Rheeder P. Effectiveness of an adapted diabetes nutrition education program on clinical status, dietary behaviors and behavior mediators in adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 2021;20(1):293–306. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00744-z.

Paes-Barreto JG, Silva MIB, Qureshi AR, Bregman R, Cervante VF, Carrero JJ, et al. Can renal nutrition education improve adherence to a low-protein diet in patients with stages 3 to 5 chronic kidney disease? Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2013;23(3):164–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2012.10.004.

Power JEM, Lee O, Aspell N, McCormack E, Loftus M, Connolly L, et al. RelAte: Pilot study of the effects of a mealtime intervention on social cognitive factors and energy intake among older adults living alone. British Journal of Nutrition. 2016;116(9):1573–81. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s000711451600369x.

Wallace R, Lo J, Devine A. Tailored nutrition education in the elderly can lead to sustained dietary behaviour change. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2016;20(1):8–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0669-2.

Johari SM, Shahar S, Ng TP, Rajikan R. A preliminary randomized controlled trial of multifaceted educational intervention for mild cognitive impairment among elderly Malays in Kuala Lumpur. International Journal of Gerontology. 2014;8(2):74–80. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijge.2013.07.002.

Keller HH, Hedley MR, Wong SS, Vanderkooy P, Tindale J, Norris J. Community organized food and nutrition education: participation, attitudes and nutritional risk in seniors. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2006;10(1):15–20.

Hien VTT, Khan NC, Lam NT, Phuong TM, Nhung BT, Van Nhien N, et al. Effect of community-based nutrition education intervention on calcium intake and bone mass in postmenopausal Vietnamese women. Public health nutrition. 2009;12(5):674–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980008002632.

Rydwik E, Lammes E, Frändin K, Akner G. Effects of a physical and nutritional intervention program for frail elderly people over age 75. A randomized controlled pilot treatment trial. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2008;20(2):159–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03324763.

Keller HH, Gibbs A, Wong S, Vanderkooy PD, Hedley M. Men can cook! Development, implementation, and evaluation of a senior men’s cooking group. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly. 2004;24(1):71–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/j052v24n01_06.

Garcia AL, Reardon R, McDonald M, Vargas-Garcia EJ. Community interventions to improve cooking skills and their effects on confidence and eating behaviour. Current nutrition reports. 2016;5(4):315–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-016-0185-3.

O’Brien N, Heaven B, Teal G, Evans EH, Cleland C, Moffatt S, et al. Integrating evidence from systematic reviews, qualitative research, and expert knowledge using co-design techniques to develop a web-based intervention for people in the retirement transition. Journal of medical Internet research. 2016;18(8):e210. doi: https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5790.

Sanchez-Villagomez P, Zurlini C, Wimmer M, Roberts L, Trieu B, McGrath B, et al. Shift to Virtual Self-Management Programs During COVID-19: Ensuring Access and Efficacy for Older Adults. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9:663875. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.663875.

Goldberg EM, Jiménez FN, Chen K, Davoodi NM, Li M, Strauss DH, et al. Telehealth was beneficial during COVID-19 for older Americans: A qualitative study with physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(11):3034–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17370.

Elbaz S, Cinalioglu K, Sekhon K, Gruber J, Rigas C, Bodenstein K, et al. A Systematic Review of Telemedicine for Older Adults With Dementia During COVID-19: An Alternative to In-person Health Services? Frontiers in Neurology. 2021;12:761965. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.761965.

Choi NG, DiNitto DM, Marti CN, Choi BY. Telehealth Use Among Older Adults During COVID-19: Associations With Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics, Technology Device Ownership, and Technology Learning. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2022;41(3):600–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211047347.

Lee K, Nathan-Roberts D. Using Visual Aids to Supplement Medical Instructions, Health Education, and Medical Device Instructions. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care. 2021;10(1):257–62. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2327857921101190.

Brownie S. Older Australians’ views about the impact of ageing on their nutritional practices: Findings from a qualitative study. Australasian journal on ageing. 2013;32(2):86–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00607.x.

Acknowledgement

Acknowledgement and thanks to Debbie Booth (Research and Scholarly Communication Advisor) for her invaluable guidance on conducting the search. Thanks are extended toward Maryam Alghamdi’s sponsors; Taibah University and the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission, for the grant support.

Funding

Funding: None reported / no funding was received for this review. Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest: All authors have no interests to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Alghamdi, M.M., Burrows, T., Barclay, B. et al. Culinary Nutrition Education Programs in Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Scoping Review. J Nutr Health Aging 27, 142–158 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-022-1876-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-022-1876-7