Abstract

Introduction

Oxycodone ARIR is a novel oral, abuse-deterrent, immediate-release (IR) formulation with physical and chemical properties that deter misuse and abuse by non-oral routes. In this single-dose pharmacokinetic study, we assessed the relative bioavailability of oxycodone for Oxycodone ARIR and IR oxycodone, and the effect of food on Oxycodone ARIR following oral administration.

Methods

This open-label, randomized study in healthy adults compared the relative bioavailability of Oxycodone ARIR 30 mg to IR oxycodone 30 mg under fasted conditions, and Oxycodone ARIR under fed versus fasted conditions. Pharmacokinetic parameters included area under the concentration–time curve from time 0 to the last measured concentration (AUC0–t) and the maximum oxycodone plasma concentration (Cmax). Equivalence was determined using an analysis of variance of the least-squares means.

Results

Fifty-eight subjects completed the study. Under fasted conditions, AUC0–t was 4% lower (90% CI 92.5–98.7%) and mean Cmax was 14% lower (90% CI 78.8–94.3%) for Oxycodone ARIR versus IR oxycodone. AUC0–t was 23% higher (90% CI 119.1–127.0%) and mean Cmax was higher (90% CI 108.6–129.4%) when Oxycodone ARIR was administered in the fed versus fasted state. Common adverse events included nausea, headache, and dizziness.

Conclusion

In this single-dose pharmacokinetic evaluation, fasted Oxycodone ARIR 30 mg had similar bioavailability to and is expected to have the same efficacy and safety profile as IR oxycodone. When administered in the fed state, pharmacokinetic parameters were slightly higher; however, these differences were considered not clinically meaningful and show that Oxycodone ARIR can be administered with or without food.

Funding

This study was funded by Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. funded the journal’s article processing charges and open access fee.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain Language Summary

Oxycodone is an opioid medication prescribed by doctors to treat moderate-to-severe pain when alternative therapies are ineffective. Immediate-release (IR) oxycodone is a tablet or capsule that is formulated to release oxycodone immediately after it is taken. IR oxycodone is prescribed to patients after surgery and for pain that occurs with conditions such as arthritis, fibromyalgia, and others. Unfortunately, IR oxycodone can be tampered with and misused. During the last 20 years, overdose deaths have increased. To tackle this very serious problem, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wants drug makers to develop new opioid formulations to help prevent misuse and abuse. Oxycodone ARIR is a new opioid formulation with physical and chemical properties that impede tampering and deter abuse.

The present investigation studied how the body absorbs oxycodone from Oxycodone ARIR when taken with and without food. To do this, we compared Oxycodone ARIR with a standard IR oxycodone formulation. Fifty-eight adults with no history of drug or alcohol addiction or abuse completed our study. Participants received one 30-mg Oxycodone ARIR tablet after fasting overnight for about 10 h, one 30-mg IR oxycodone tablet after similar fasting time, and one 30-mg Oxycodone ARIR tablet 30 min after eating a high-fat meal; each tablet was given to subjects at least 4 days apart. We discovered that Oxycodone ARIR has similar absorption characteristics as IR oxycodone when subjects fasted. During the study, subjects reported nausea, vomiting, indigestion, and headache, which are typical problems associated with opioids. We conclude that Oxycodone ARIR is expected to be just as effective and safe as IR oxycodone.

Introduction

Prescription opioids are often targeted for misuse and abuse, with the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, reporting their misuse by approximately 11.5 million individuals aged 12 years or older in the USA in 2016 [1]. There has been a steady increase in deaths resulting from overdoses associated with prescription opioids with 17,087 deaths involving overdose associated with prescription opioids in 2016, equivalent to about 47 people dying every day [2].

To achieve enhanced psychoactive effects of the drug, opioid abusers use several methods of abuse, including ingesting a larger-than-prescribed dose of intact tablets/capsules orally. Abusers also use alternative routes of administration, including intranasal and intravenous injection, after physical manipulation and/or chemical extraction. These alternative routes of administration yield quicker delivery of the drug to the brain resulting in a potent and rapid feeling of euphoria or “high” [3, 4].

The US FDA encourages the development of abuse-deterrent formulations (ADFs), and has developed final guidance for industry on the evaluation and labeling of ADFs [5]. Currently, seven extended-release (ER) and one immediate-release (IR) ADFs have been approved with labeling consistent with the FDA’s guidance [6].

Instant release of opioids from IR formulations is an important factor in deciding the route of administration among prescription opioid abusers; abusers prefer IR opioids for their ability to produce a quick high without needing too much manipulation to prepare the IR opioid for non-oral administration [7]. Findings from a recent study indicated that 66% of advanced opioid abusers prefer IR opioids, compared with only 4% preferring ER opioids [8].

Oxycodone abuse-resistant immediate-release (ARIR) (RoxyBond™, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Basking Ridge, NJ, USA) is the only FDA-approved IR opioid with ADF labeling. Oxycodone ARIR is formulated with proprietary SentryBond™ technology (Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC, Morristown, NJ) and has physical and chemical properties to deter abuse [9]. The active ingredient is contained within a polymer matrix of inactive ingredients. The active ingredient is difficult to visually distinguish or physically separate from the polymer matrix (Daiichi Sankyo data on file). Oxycodone ARIR is expected to deter abuse by the intranasal and intravenous routes of administration; however, abuse by the intranasal, oral, and intravenous routes is still possible [9]. Crushed intranasal Oxycodone ARIR has demonstrated a significant reduction in drug liking (Emax) and “take drug again” scores (Emax) compared with crushed intranasal IR oxycodone and intact oral Oxycodone ARIR [10]. Crushed intranasal Oxycodone ARIR also exhibited lower peak oxycodone plasma concentrations and slower time-to-peak concentration compared with crushed intranasal IR oxycodone, thus signifying the potential of Oxycodone ARIR to reduce abuse via the intranasal route [10]. In this single-dose pharmacokinetic (PK) study, we assessed the relative bioavailability of oxycodone for Oxycodone ARIR and IR oxycodone, and the effect of food on Oxycodone ARIR following oral administration.

Methods

Subjects

Healthy male and female adults aged 18 to 45 years with a body mass index (BMI) of 18.0–32.0 kg/m2 were enrolled in the study. All female subjects enrolled in the study must have been using at least one form of birth control, been surgically sterilized, or been of non-childbearing potential. Male subjects were required to use a form of birth control or have had a vasectomy. Subjects who were pregnant, lactating, or breastfeeding were excluded from the study. Positive drug screens or receipt of an investigational drug within 30 days before dosing resulted in exclusion from study participation. Other exclusions included a history of allergic responses to oxycodone hydrochloride, naltrexone or other related drugs, and a history of drug or alcohol addiction or abuse within the past year. The per-protocol population was defined as all subjects who completed at least two treatment periods of the study, with one of those periods representing the results for Oxycodone ARIR fasted, subjects who provided adequate data for estimates of PK parameters in both periods, and subjects who did not have any major protocol deviations.

The study was implemented in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013, concerning human and animal rights, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, local regulatory requirements, and US FDA Code of Federal Regulations, and Springer’s policy concerning informed consent has been followed. The protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the New England Institutional Review Board (approval on January 9, 2013). After receiving a sufficient explanation and achieving a full understanding of the study, all potential participants provided written consent to voluntarily participate in the study.

Study Design and Treatment

This study was an open-label, randomized, single-dose, three-period, three-treatment, six-sequence crossover study. The study included a study check-in day (day 1), followed by 2 days of participation in the study, and study exit (day 2) or early termination. A minimum washout period of 4 days separated each treatment. Subjects were required to stay at the clinic facility for 24 h after day 1 dosing.

The three treatments in the study included administration of Oxycodone ARIR 30-mg tablet and IR oxycodone 30-mg tablet under fasting conditions and administration of Oxycodone ARIR 30 mg under fed conditions. For the fasting condition, subjects were given a single dose of the test product, Oxycodone ARIR 30-mg tablet, or the reference product, IR oxycodone (Roxicodone®, Xanodyne Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Newport, KY, USA) 30-mg tablet, with 240 mL (8 fluid ounces) of room temperature water after an overnight fast of at least 10 h. For the fed condition, subjects underwent an overnight fast of at least 10 h, and were given a single dose of Oxycodone ARIR 30 mg with 240 mL of room temperature water 30 min after consuming a standardized meal. The standardized meal was high fat (approximately 50% of the total caloric content of the meal) and high calorie (approximately 800 to 1000 calories).

To block the major effects of oxycodone, subjects were given naltrexone (Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, St. Louis, MO, USA) 50 mg with 240 mL of water at approximately 12 h (± 30 min) before oxycodone administration, within 1.5 h (± 15 min) of oxycodone administration, and approximately 12 h (± 30 min) after oxycodone administration.

Pharmacokinetic Assessment

Blood samples were taken within 90 min before each subject’s scheduled dose time and after dose administration at 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 12, 16, and 24 h. Pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated using standardized, non-compartmental approaches. The following parameters were evaluated for oxycodone plasma concentration: the area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time 0 to the last measured concentration (AUC0–t), the area under the plasma concentration versus time curve from time to 0 infinity (AUC0–∞), the maximum plasma concentration observed over a time span (Cmax), and the time where the maximum plasma concentration or Cmax is observed (Tmax). The oxycodone plasma concentrations were measured by using a validated bioanalytical method completed by Sannova Analytical, Inc. (Somerset, NJ) according to the bioanalytical laboratory’s standard operating procedures and FDA guidelines.

Safety Assessment

The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 15.0 was used to code adverse events (AEs). All AEs, observed, queried, or spontaneously offered by subjects, were recorded. An AE inquiry was completed approximately every 12 h throughout the stay in the clinic facility, when subjects were released from the facility, and at each return visit.

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 70 subjects was calculated to provide 90% power to show that the test-to-reference confidence intervals (CIs) were within the 80–125% equivalence range. Analyses of the study were conducted with Statistical Analysis System (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA) version 9.2 or later. Descriptive statistics such as mean, median, standard deviation, standard error or mean, coefficient of variation, minimum, maximum, and number of subjects were calculated for each PK parameter and sampling time concentration for both test and reference products.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to model loge and was used to transform parameter values of the AUC0–t, AUC0–∞, and Cmax for the per-protocol population (defined as subjects who had completed at least two treatment periods, provided data for estimates of AUC and Cmax parameters in both periods, and did not have any major protocol deviations). Each ANOVA included calculation of least-squares means (LSMs), the difference between the adjusted formulation means, and the standard error of the difference. Statistical analyses were completed using the Proc Mixed analysis in SAS.

A 90% CI for the difference in the means between the test and the reference treatments was calculated for the log-scale value of each parameter. Confidence intervals were based off the estimated LSMs using a mean square error from the ANOVA models. The endpoints of the CIs were back-transformed to acquire CIs for the test-to-reference ratio of the geometric means from each parameter on the original scale expressed as a percentage. Analyses of the Tmax were completed by comparing the medians by ranking the values within subjects and by an ANOVA model performed on the ranks. The median and range for the Tmax for each treatment and the differences between medians of the two treatments of interest were provided. Statistical comparisons were made between Oxycodone ARIR (fasted) versus IR oxycodone (fasted) and Oxycodone ARIR fed versus fasted.

Results

Subjects

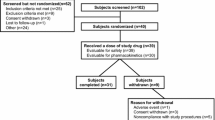

Of the 75 subjects enrolled, 58 completed the study (Fig. 1). Of the 17 subjects who discontinued prematurely, 10 discontinued because of AEs, 6 withdrew of their own accord, and 1 was lost to follow-up. Demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. In the safety population, which included all subjects who received at least one dose of the study medication, most subjects were male (74.7%) and white (92.0%). The mean age was 25.7 years and mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2.

Pharmacokinetic Analysis

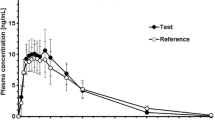

Fasted Conditions: Oxycodone ARIR Versus IR Oxycodone

The mean plasma concentrations over time for Oxycodone ARIR and IR oxycodone are shown in Fig. 2. AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ were each slightly lower (4%) for Oxycodone ARIR than for IR oxycodone (Table 2). The mean Cmax for Oxycodone ARIR was 14% lower than for IR oxycodone (57.8 versus 67.7 ng/mL). The 90% CIs for Oxycodone ARIR and IR oxycodone were within the equivalence range of 80–125% for total exposure (AUC0–t 92.5–98.7% and AUC0–∞ 92.8–98.9%) (Table 3). The 90% CI for Cmax was outside the 80–125% equivalence range (78.8–94.3%). The median Tmax was 30 min longer for Oxycodone ARIR compared with IR oxycodone (1.8 versus 1.0 h, respectively; LSMs difference, 0.48 h).

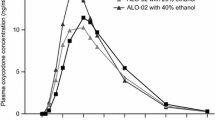

Fed Versus Fasted Conditions: Oxycodone ARIR

The mean plasma concentrations over time for Oxycodone ARIR under fed and fasted states are shown in Fig. 3. AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ were 23% and 24% higher, respectively, when Oxycodone ARIR was administered in the fed versus fasted state (Table 2). Mean oxycodone Cmax was 18% higher (68.0 versus 57.8 ng/mL) under fed compared with fasted conditions. The 90% CIs were outside the equivalence range of 80–125% for total exposure (AUC0–t 119.1–127.0%; AUC0–∞ 119.7–127.4%) and for Cmax (108.6–129.4%) (Table 3). The median Tmax for Oxycodone ARIR was 30 min longer in the fed versus fasted state (2.0 versus 1.8 h, respectively; LSMs difference, 0.5 h).

Safety Assessment

AEs were typical of opioid-related events and were mild or moderate in severity. Nausea, headache, and dizziness occurred more often with the Oxycodone ARIR treatment given to fasted subjects than the fed subjects or the subjects who received IR oxycodone (Table 4). Common AEs included gastrointestinal disorders such as nausea, vomiting, or dyspepsia, and nervous system disorders such as dizziness, headache, and somnolence. Eight subjects withdrew from the study because of nausea and/or vomiting during the naltrexone treatment. One subject withdrew from the study prematurely during Oxycodone ARIR treatment under fed conditions because of headache; one subject who received IR oxycodone treatment withdrew from the study prematurely because of vomiting.

Discussion

Prescription opioid overdose is associated with 47 deaths each day on an average in the USA, making the misuse and abuse of prescription opioids a national health crisis [2]. To combat the problem of opioid abuse, several organizations including the FDA, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the Department of Health and Human Services have implemented a multifaceted opioid risk management plan over the past few years [11]. The FDA encourages the development of ADFs of opioids to combat abuse and considers this approach to be a high public health priority [5]. To minimize the adverse effects of opioid abuse, most ADFs have been designed to deter the potential for abuse by physical manipulation and/or chemical extraction and administration through non-oral routes, while providing the same pain relief as non-ADF opioids [12].

This study investigated the relative bioavailability of Oxycodone ARIR to IR oxycodone in healthy adults. Under fasted conditions, AUC0–t and AUC0–∞ were 4% lower for Oxycodone ARIR than for IR oxycodone. The mean Cmax for Oxycodone ARIR was 14% lower than for IR oxycodone. Because of the wide intersubject variability in opioid absorption and metabolism, opioid dosing must be titrated to effect for each individual; therefore, these lower measurements are not expected to be clinically meaningful. The abuse quotient (AQ = Cmax/Tmax) is an indicator of the abuse potential of the formulation, where a higher AQ indicates a larger, quicker “high” for the abuser [13]. When compared with IR oxycodone, Oxycodone ARIR had a lower Cmax and a longer Tmax, indicating a lower AQ and potentially a lower abuse potential.

Food can alter the PK of some ADFs [14, 15]. High-fat meals may delay Cmax or increase bioavailability [14,15,16,17]. When Oxycodone ARIR was taken with food, the oxycodone Cmax was 18% higher and Tmax was 30 min longer than in the fasted conditions. In a single-dose PK study, a Cmax outside the confidence interval is less significant than if the AUC is outside the limits, as AUC is an indicator of the overall exposure. Oxycodone ARIR exhibited a 24% increase in total exposure when administered with a high-fat meal. Pharmacokinetic evaluations of other immediate-release oxycodone formulations have shown similar results [16, 17]. We and the FDA considered these differences to be moderate, indicating that Oxycodone ARIR can be administered with or without food and requires no specific food-related dosing requirements in the product’s prescribing information. In comparison, another currently marketed oxycodone ADF exhibits a 50% to 60% increase in AUC when administered with a high-fat, high-calorie meal; the food effect with that formulation required a recommendation in the prescribing information to instruct patients to take each dose of the formulation with the same amount of food to avoid fluctuations in plasma drug levels [18]. Non-ADF IR oxycodone exhibits a 27% increase in total exposure and a 1.3-h delay in maximum plasma concentration when administered with a high-fat meal [19], indicating that the effect of food on the bioavailability of Oxycodone ARIR is a property of oxycodone PK parameters, rather than the abuse-deterrent formulation.

The most common AEs were gastrointestinal disorders (i.e., nausea, vomiting, and dyspepsia) followed by nervous system disorders (dizziness, headache, and somnolence) consistent with the safety information provided for IR oxycodone [9]. All AEs were mild or moderate in severity and typical of opioid-related AEs. Of note, a common side effect of naltrexone is nausea [20]. Together, these data show that Oxycodone ARIR has similar bioavailability to the reference-listed drug, IR oxycodone.

Limitations

The use of naltrexone to block the pharmacodynamic effects of oxycodone is a potential limitation of this study. Opioids induce delay of gastric emptying (i.e., constipation); naltrexone may reverse this effect, possibly altering the assessment of PK parameters [21]. There is some potential overlap between the AEs caused by opioid administration and those induced by naltrexone, primarily nausea [20]. In theory, it is possible that in blocking the binding of opioids to opioid receptors and transporters, naltrexone may inadvertently increase the plasma concentrations of opioids; more in-depth pharmacological and pharmacokinetic studies are needed to prove this effect. Further, in clinical practice (and in the absence of naltrexone), opioids are always titrated to effect for each patient, so the naltrexone-related effect on PK parameters would be irrelevant. However, the use of naltrexone in PK studies in opioid ADFs is recommended by the FDA [5].

Another potential limitation of this study is that the majority of subjects were white. Because different races can carry alternate alleles of the cytochrome P450 drug-metabolizing enzymes [22], it is possible that other races would exhibit different pharmacokinetic results. However, because of the crossover design of the study, any racial or ethnic differences in drug metabolism or drug transport would apply to all evaluated treatments and would thereby not affect the conclusions of the study. Other limitations of the study include exclusion of adults over 45 years of age and of subjects with a BMI greater than 32 kg/m2. These factors may impact the generalizability of the findings across the US population at large.

Of note, a sample size of 70 subjects was calculated to demonstrate differences between treatments; however, only 58 subjects completed the study. It is possible that a larger number of subjects could have demonstrated more refined values that more clearly fell within or outside the equivalence range, not just marginally outside the equivalence range. A large number of subjects (n = 10) withdrew after naltrexone administration but before randomization to the treatment groups; it is unclear why this occurred. Further studies with a larger population could clarify these discrepancies.

This study follows the FDA’s requirement for a 505(b)(2) submission, which relies on the established efficacy and safety of IR oxycodone. Because of the similar bioavailability between the two formulations, Oxycodone ARIR is expected to have the same efficacy and safety profile as IR oxycodone. Patients can be converted from IR oxycodone to the same dose and dosing regimen of Oxycodone ARIR; however, much like non-ADF opioids, Oxycodone ARIR should be titrated to the lowest dose that provides effective pain relief.

Conclusion

In this single-dose PK study, Oxycodone ARIR has similar bioavailability to IR oxycodone, and Oxycodone ARIR is expected to have the same efficacy and safety profile as IR oxycodone when taken as indicated. In addition, these data indicate that Oxycodone ARIR can be administered without regard to food.

References

Ahrnsbrak R, Bose J. Key Substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review 2017. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/Key-Substance-Use-and-Mental-Health-Indicators-in-the-United-States-/SMA17-5044. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid data analysis. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/analysis.html. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Budman SH, Grimes Serrano JM, Butler SF. Can abuse deterrent formulations make a difference? Expectation and speculation. Harm Reduct J. 2009;6:8.

Katz N, Dart RC, Bailey E, Trudeau J, Osgood E, Paillard F. Tampering with prescription opioids: nature and extent of the problem, health consequences, and solutions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(4):205–17.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Abuse-deterrent opioids: evaluation and labeling: guidance for industry; 2015.

US Food and Drug Administration. Abuse-deterrent opioid analgesics. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm600788.htm. Accessed 10 Oct 2018.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. Oral and non-oral routes of administration among prescription opioid users: pathways, decision-making and directionality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:11–6.

Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Kasper ZA. Relative preferences in the abuse of immediate-release versus extended-release opioids in a sample of treatment-seeking opioid abusers. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(1):56–62.

RoxyBond (oxycodone HCl) [package insert]. Basking Ridge, NJ: Daiichi Sankyo. 2018.

Webster LR, Iverson M, Pantaleon C, Smith MD, Kinzler ER, Aigner S. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled, intranasal human abuse potential study of oxycodone ARIR, a novel, immediate-release, abuse-deterrent formulation. Pain Med. 2019;20(4):747–757.

Brady KT, McCauley JL, Back SE. Prescription opioid misuse, abuse, and treatment in the United States: an update. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(1):18–26.

Katz N. Abuse-deterrent opioid formulations: are they a pipe dream? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10(1):11–8.

Moorman-Li R, Motycka CA, Inge LD, Congdon JM, Hobson S, Pokropski B. A review of abuse-deterrent opioids for chronic nonmalignant pain. P T. 2012;37(7):412–8.

FDA Briefing Document (Avridi). 2015; Joint Meeting of the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee. https://www.fdanews.com/ext/resources/files/09-15/9-15-FDA-Briefing.pdf?1520642200. Accessed 22 Oct 2018.

FDA Briefing Document (Xtampza). 2015; Joint Meeting of the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee. https://www.pharmamedtechbi.com/~/media/Supporting%20Documents/The%20Pink%20Sheet%20DAILY/2015/September/Collegium_oxycodone_AC_FDA_brfg.pdf. Accessed 22 Oct 2018.

Bass A, Stark JG, Pixton GC, et al. Dose proportionality and the effects of food on bioavailability of an immediate-release oxycodone hydrochloride tablet designed to discourage tampering and its relative bioavailability compared with a marketed oxycodone tablet under fed conditions: a single-dose, randomized, open-label, 5-way crossover study in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther. 2012;34(7):1601–12.

Benziger DP, Kaiko RF, Miotto JB, Fitzmartin RD, Reder RF, Chasin M. Differential effects of food on the bioavailability of controlled-release oxycodone tablets and immediate-release oxycodone solution. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85(4):407–10.

Xtampza ER (oxycodone) extended-release capsules [package insert]. Stoughton, MA: Collegium Pharmaceutical, Inc. 2018.

Roxicodone (oxycodone HCl) [package insert]. Hazelwood, MO: Mallinckrodt Brand Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2016.

Naltrexone hydrochloride [package insert]. Webster Groves, MO: Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals. 2017.

Holzer P. Pharmacology of opioids and their effects on gastrointestinal function. Am J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2014;2:9–16.

Zhou Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Lauschke VM. Worldwide distribution of cytochrome P450 alleles: a meta-analysis of population-scale sequencing projects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(4):688–700.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This study was funded by Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Daiichi Sankyo, Inc. funded the journal’s article processing charges and open access fee.

Medical Writing Assistance

Medical writing support in the preparation of this article was provided by Bhawana Bariar, MS, PhD, and Kelly M Cameron, PhD, ISMPP Certified Medical Publication Professional™ of JB Ashtin (Plymouth MI, USA). Support for this assistance was provided by Daiichi Sankyo, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship of this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Prior Presentations

(1) Webster L, et al. The relative bioavailability of Oxycodone ARIR (RoxyBond™), a novel abuse-deterrent formulation of immediate-release oxycodone, compared to immediate-release oxycodone. Presented at the International Conference on Opioids; June 10–12, 2018; Boston, MA. 2018. (2) Webster L, et al. The effect of food on the pharmacokinetic characteristics of Oxycodone ARIR (RoxyBond™), a novel abuse-deterrent formulation of immediate-release oxycodone. Presented at PAINWeek 2018; September 4–8, 2018; Las Vegas, NV. 2018. (3) Webster L, et al. The relative bioavailability of Oxycodone ARIR (RoxyBond™), a novel abuse-deterrent formulation of immediate-release oxycodone, compared to immediate-release oxycodone. Presented at PAINWeek 2018; September 4–8, 2018; Las Vegas, NV. 2018.

Disclosures

Lynn Webster is an employee of PRA Health Sciences. He has received honorarium for consulting or advisory boards from Alcobra, Daiichi Sankyo, Egalet, Elysium, Inspirion, Insys, Kempharm, Pain Therapeutics, Pfizer, Shionogi, and Teva. Eric R. Kinzler is an employee of or consultant for Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC., and may own stock or have stock options. Carmela Pantaleon is an employee of or consultant for Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC., and may own stock or have stock options. Matthew Iverson is an employee of or consultant for Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC., and may own stock or have stock options. Stefan Aigner is an employee of or consultants for Inspirion Delivery Sciences, LLC., and may own stock or have stock options.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was implemented in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013, concerning human and animal rights, the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines, local regulatory requirements, and United States Food and Drug Administration Code of Federal Regulations, and Springer’s policy concerning informed consent has been followed. The protocol and informed consent form were reviewed and approved by the New England Institutional Review Board. After receiving a sufficient explanation and achieving a full understanding of the study, all potential participants provided written consent to voluntarily participate in the study.

Data Availability

Deidentified individual participant data (IPD) and applicable supporting clinical trial documents may be available upon request at https://www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-DS.aspx.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8010635.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Webster, L.R., Kinzler, E.R., Pantaleon, C. et al. Relative Oral Bioavailability of an Abuse-Deterrent, Immediate-Release Formulation of Oxycodone, Oxycodone ARIR in a Randomized Study. Adv Ther 36, 1730–1740 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00963-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00963-0