Abstract

Introduction

It was hypothesized that patients experiencing at least one tacrolimus formulation switch may require more frequent therapeutic drug monitoring, subsequent dose adjustments, and a potential for untoward clinical outcomes than patients who remain on a single formulation.

Methods

Eligible patients were adult kidney transplant recipients with stable renal function at month 3 post-transplant and no evidence of acute rejection, receiving an oral, tacrolimus-based regimen. Patients were categorized into two groups (fixed or variable formulation) using the US National Drug Code (NDC) on the basis of tacrolimus formulation usage over the 12-month period.

Results

A total of 305 patients were enrolled from four US transplant centers; 44 (14.4%) received multiple formulations and 261 (85.6%) received a single formulation. Mean number of tacrolimus dose adjustments and mean cumulative milligram dose change were not statistically different between the two groups. Mean trough-to-dose ratio, frequency of trough level measurements, and mean number of excursions above 120% or below 80% of the patient’s mean trough concentration were significantly higher in the variable compared to the fixed formulation group.

Conclusion

A variable tacrolimus formulation regimen was associated with a higher frequency of trough level measurements and a greater number of excursions in trough levels compared with continuing on a fixed formulation regimen of tacrolimus in this retrospective chart review study.

Funding

Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc.

Plain Language Summary

Plain language summary available for this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Plain Language Summary

This retrospective study reviewed medical charts of patients who had kidney transplants in the USA from 2009 to 2013. The study aimed to determine whether switching between tacrolimus “formulations” (“brand” or “generic”) after kidney transplant was associated with adverse consequences when compared to remaining on a single tacrolimus “formulation.” Results showed that patients who received different formulations are monitored more often for therapeutic drug levels and experience more changes in levels of their medication than patients who remain on a single formulation of tacrolimus after kidney transplantation. Results did not show a significant difference between patients with the same or different tacrolimus formulations with regard to outcomes such as loss of the transplanted kidney or death.

Introduction

Tacrolimus is a macrolide-derived calcineurin inhibitor widely used as an immunosuppressant for preventing rejection in solid organ transplantation. Noteworthy is its narrow therapeutic index, which requires routine drug monitoring to assist the clinician in mitigating the potential for over- or under-immunosuppression, and the potential consequences thereof [1].

Tacrolimus was first approved by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1994 under the brand name Prograf® (Astellas Pharma, Ltd. Chertsey, UK). Subsequently, numerous generic formulations of tacrolimus have been approved on the basis of the FDA’s rules of bioequivalence. To establish pharmacokinetic bioequivalence in the USA, the calculated 90% confidence interval for the ratio of product averages for maximum concentration (Cmax) and area under the curve (AUC) [2] of the generic formulation should fall within 80–125% of the reference product [3]. This bioequivalence paradigm has proven controversial for drugs of narrow therapeutic index such as tacrolimus since the transplant population may not be accurately simulated in healthy volunteers [4, 5]. Moreover, generic preparations are approved against the reference-branded product and not each other, leading to questions regarding drug exposure when switches are made between various formulations [2].

A number of studies have evaluated the potential clinical and cost effects of converting from Prograf® to a generic formulation [6,7,8]. These studies consistently showed that tacrolimus dose requirements and trough concentrations were similar post-conversion. However, additional drug monitoring post-conversion was recommended. In the multicenter, controlled study by Momper et al. [7] there was a decrease in trough concentrations after switching to a generic formulation, but there were no differences in short-term outcomes compared with those who did not switch. Yet, the patients who switched necessitated a greater number of trough level measurements post-conversion to maintain trough concentrations within patient-specific target ranges. The authors indicated that the results suggest that the most significant risk may be if patients are switched from one generic product to another, potentially resulting in a difference in AUC or Cmax of greater than 20%. However, recently, Alloway and associates published the results of their randomized, three-treatment, six-period crossover bioequivalence study that compared the innovator and two generic formulations of tacrolimus in stable kidney and liver transplant patients. All three products fell within the FDA’s average bioequivalence acceptance criteria as well as the scaled average bioequivalence criteria, which took into account inter-patient variability [9].

The present study was designed to perform a real-world evaluation describing the extent of tacrolimus formulation switching post-transplantation, to assess the variability in tacrolimus trough concentrations, and to catalogue the number of dose adjustments in kidney transplant patients who maintained a fixed treatment regimen versus a variable treatment regimen. Additional explorations were undertaken to assess the clinical and healthcare utilization burden of these treatment regimens during the 3- to 15-month post-transplantation observation period.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective, cohort, observational, non-randomized study of adult patients who received a kidney transplant in US transplant centers during or after September 2009. Patients required stable renal function at month 3 post-transplantation, no evidence of acute rejection, and ongoing treatment with an oral, tacrolimus-based, maintenance immunosuppression regimen. The transplant period was chosen to reflect the era of potential generic tacrolimus substitution, the first generic having been approved in August 2009. To minimize any potential temporal bias, patients were selected on the basis of the date of transplantation across three time periods: period 1—September 1, 2009, to December 31, 2010; period 2—January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011; and period 3—January 1, 2012, to March 31, 2013 (or later). Data were then collected from the index date of kidney transplantation onward, with a planned sample size of 816 patients. Approximately one-third of the patients enrolled at each study center had their index transplant within one of the individual time periods.

This study was a retrospective chart review. No specific procedures or interventions were required or specified in the protocol. The study was conducted in accordance with applicable policies and requirements at the following sites: California Pacific Medical Center [Sutter Health Institutional Review Board (IRB)], Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland Clinic IRB), Lehigh Valley Hospital (Lehigh Valley Health Network IRB), Massachusetts General Hospital (Partners Human Research Committee), University of Utah (University of Utah IRB), and Washington University (Washington University Human Research Protection Office), and in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. All sites submitted an informed consent waiver with IRB applications, as this study used de-identified patient data for a retrospective medical chart review. This trial was not registered with ClinicalTrials.gov because of the non-interventional, retrospective nature of the study.

Fixed Versus Variable Tacrolimus Formulation Regimen

Patients were categorized into the fixed or variable formulation groups on the basis of their tacrolimus formulation usage as identified by US National Drug Codes (NDCs) over the 12-month (months 3–15 post-kidney transplantation) observation period (Fig. 1). The NDC number is a unique identifier, assigned by the FDA to a pharmaceutical product in the USA, which distinguishes the labeler, the product, and the commercial package size. For the present study, a fixed regimen was classified as remaining on a single tacrolimus formulation, whilst switching between formulations was classed as a variable regimen. Specifically, a variable formulation regimen was defined as a change in NDC within a specific dose strength or a dose adjustment that resulted in a change in NDC for one or more continuing dose strengths. All other patients were categorized as having received a fixed formulation regimen. This included patients who received a dose adjustment that did not deviate from their continuing dose strength formulation, or those who experienced a dose adjustment discontinuing all dose strengths for an entirely new dose strength, regardless of NDC, as no individual dose strengths underwent a change in NDC in this case.

Study Population

Eligible patients were at least 18 years of age at the time of transplantation who had received a kidney-only transplant (living or deceased donor, primary or re-transplant) during or after September 2009. For eligibility, a complete patient data set was required from the time of transplant to either the time of graft loss, death, or elapse of 15 months following transplantation, whichever occurred first. To ensure that the impact of formulation could be reliably compared, clinical stability was required for all patients, defined as a serum creatinine below 1.5 mg/dL at 3 months post-transplantation without occurrence of acute rejection. Patients with fewer than three tacrolimus trough concentration values during the 12-month period or who had become pregnant during the 15-month study period were excluded.

Sample Size

The planned sample size was based on data reported by Borra et al. [10] that demonstrated an expected number of dose adjustments during the 12-month post-transplant period to be 1.22 per patient. It was estimated that 816 patients were required to achieve an 80% power for detection of a clinically significant increase (α = 0.05, two-sided significance) based on a standard deviation (SD) of 1.15 dose adjustments per patient and an expected difference of at least 25% in the number of dose adjustments per patient in the variable compared with the fixed treatment regimen.

Data Collection

Donor and recipient baseline characteristics, transplant-related information, tacrolimus dosing and trough concentration, and clinical outcome data were obtained through electronic transfer of electronic medical records (EMR) by the site into the study database. All data were de-identified prior to transfer. Information on tacrolimus dose and NDC number were obtained from hospital or outpatient pharmacy records by the study site.

Study Endpoints

Study endpoints included the number of tacrolimus dose adjustments; cumulative milligram dose changes in tacrolimus; number of excursions above 120% or below 80% of mean tacrolimus trough level for each patient; frequency of therapeutic drug monitoring; tacrolimus trough to dose ratio; incidence of acute rejection, graft loss, and death; and healthcare utilization. Measures of healthcare utilization included the number of patients hospitalized; the number of inpatient, emergency room, and outpatient visits, and the number of phone contacts with the transplant clinic.

For each patient, the total number of dose adjustments was determined across all visits from month 3 through month 15 post-transplantation. A dose adjustment was defined as a change in a patient’s dose for any reason. A change in tacrolimus dose from the previous visit was counted as a dose adjustment.

Excursions below 80% and above 120% were selected as a clinically meaningful difference in tacrolimus trough concentrations. The total number of excursions above 120% or below 80% of the overall mean trough level from months 3 to 15 per patient was determined using the following procedure. For each patient, the mean tacrolimus trough concentration [nanograms/milliliter (ng/mL)] was calculated on the basis of all trough concentrations reported from month 3 through month 15. Tacrolimus trough concentrations that were above 120% or below 80% of the mean were flagged and counted over the same time period.

Statistical Methods

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median and interquartile range while categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Summary statistics are compared using a general linear model, Fisher’s Exact test, or Chi-square test.

Analysis was performed using SAS statistical software (SAS v. 9.0 or higher, Cary, NC). A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No adjustments for multiplicity were made because of the exploratory nature of this observational study.

Results

Data from 305 patients from four US study sites were collected; 88 (28.9%) were from transplant period 01 September 2009 to 31 December 2010, 93 (30.5%) from 01 January 2011 to 31 December 2011, and 124 (40.7%) from 01 January 2012 to 31 March 2013. The study was stopped early because of challenges with identifying patients who met all of the study criteria (i.e., availability of tacrolimus NDC numbers for prescriptions dispensed during the study period). Of the 305 patients included in the analysis, 261 patients (85.6%) received a fixed tacrolimus formulation regimen and 44 (14.4%) met the definition of a variable tacrolimus regimen. Of these, 35 patients (79.5%) were identified from one study site.

Donor, recipient, and post-transplant allograft characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The variable tacrolimus regimen group tended to be non-white, were on dialysis longer prior to their index kidney transplant, had received an expanded criteria donor (ECD) kidney, had a higher kidney donor risk index (KDRI), and had government as their primary insurance (versus private or self-insured). Measures of renal function at 3 months post-index transplantation were comparable between the two groups.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in use of antibody induction, with the majority of patients receiving a T cell depleting agent. At month 3 post-transplant, the majority of patients were on maintenance immunosuppression with mycophenolate and/or corticosteroids in combination with tacrolimus.

Table 2 summarizes the tacrolimus formulations, the mean total daily dose, and the mean trough concentration at 3 months post-transplantation (entry into the study). Over half of the patients in the fixed tacrolimus regimen group (56%) had received branded tacrolimus (Prograf®) versus 25% in the variable tacrolimus regimen group. The mean total daily dose was also significantly lower in the variable compared with the fixed regimen group (3.69 mg versus 4.85 mg, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference in mean tacrolimus trough concentrations between the two groups at 3 months post-transplantation, nor between the groups with regard to mean number of tacrolimus dose adjustments and the cumulative milligram dose change during the observation period (Table 3). However, mean trough to dose ratio [2.22 (1.7) versus 2.02 (1.7); p < 0.001] and mean number of trough level measurements [29.2 (12.7) versus 22.6 (9.5); p < 0.001] over the 3- to 15-month period were significantly higher in the variable compared with the fixed treatment regimen (Table 3).

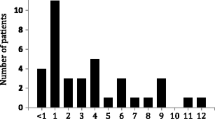

The mean (± SD) number of excursions above 120% or below 80% of the patient’s mean trough concentration was significantly higher in the variable (13.9 ± 7.9) compared with the fixed treatment regimen (10.5 ± 6.1; p < 0.001) group (Table 3). The majority of the excursions occurred from months 3 to 6 post-transplantation (mean = 4.1 ± 3.2 in the fixed versus 6.1 ± 3.6 in the variable treatment regimen; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

One patient (fixed treatment regimen) died with a functioning graft during the observation period. There were no other cases of graft failure. A total of 17 (6.5%) patients in those receiving the fixed and 2 (4.6%) patients in the variable treatment group experienced acute rejection during the 12-month interval.

Healthcare utilization, as documented in the patient’s EMR at their respective transplant center, is summarized in Table 4. There were no significant differences between tacrolimus regimen groups in the rate of hospitalization, emergency room or outpatient visits. There was, however, a significantly greater number of phone contacts with the transplant clinic in the variable versus the fixed tacrolimus regimen group.

Discussion

In any retrospective study examining transplant outcomes as a function of immunosuppressant usage, a significant operational challenge is ascertaining the specific agent used and over what length of time. This particularly holds true for an agent like tacrolimus, where there are multiple formulations available, both branded and generic. We determined that the accurate collection of such information could be gleaned from the NDC number of each individual tacrolimus product. To our knowledge, this is the first study attempting to characterize the usage of available tacrolimus formulations in this manner.

In the USA, the NDC number is a unique 10-digit, three-segment number (e.g., the NDC number for Prograf® 1 mg gelatin capsule is 0469-0607-73) present on all non-prescription and prescription medication packages as well as inserts dispensed nationwide. The first set of numbers in the NDC identifies the labeler (manufacturer, re-packager, or distributer). The second set of numbers is the product code, which identifies the specific strength, dosage form (i.e., capsule, tablet, or liquid), and formulation of a drug from a specific manufacturer. Finally, the third set is the package code, which identifies package sizes and types. The labeler code is assigned by the FDA, while the product and package codes are assigned by the labeler (https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/). Thus, by utilizing the NDC number, we were able to determine the exact tacrolimus formulation and strength dispensed to each patient.

The majority of study sites that were approached about participating in this study were unable to obtain NDC numbers for their patients over the whole study period. Most study sites were unable to reliably obtain NDC information after the patient was discharged and receiving prescriptions dispensed from community-based pharmacies. This resulted in only four study sites participating in the study and the inability to meet the required sample size. Three of the four study sites obtained NDC numbers through their hospital-based pharmacy system and the fourth study site was able to obtain NDC numbers from a large national community-based pharmacy system. Interestingly, the patients from the fourth site had the greatest proportion of variable treatment patients. This suggests that to accurately ascertain the extent of tacrolimus formulation switching, a representative sample of patients using hospital-based and community-based pharmacies would need to be included.

Despite these limitations, the data are suggestive of an association between type of tacrolimus formulation (remaining on a single formulation vs. switching between formulations) and trough measurements. The higher frequency of trough concentration measurements in the variable group is consistent with other studies evaluating the effects of switching from the innovator product to a generic [6,7,8, 11, 12].

Perhaps of potential greater clinical consequence was the significantly greater number of excursions in trough levels in the variable group compared with the fixed group. While this study did not demonstrate any significant differences between the fixed and variable group in renal function out to 15 months post-transplantation, the potential long-term consequences of repeated excursions or high intra-patient variability in tacrolimus exposure have been suggested in a number of studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Rodrigo et al. reported on a cohort of 252 deceased donor kidney transplants who were alive at least 1 year post-transplantation and who were maintained on a twice-daily regimen of tacrolimus. The median follow-up was 6 years. Patients who had a coefficient of variation (CV) of 30% or higher (CV defined as the ratio of the SD to the mean tacrolimus concentrations for all outpatient visits within 3–12 months post-transplant) had significantly worse death-censored graft survival, were independently at risk for development of death-censored graft loss, and had worse 1-year serum creatinine levels compared with those with lower variability [3]. Because of the potential long-term consequences of variability in tacrolimus exposure, it would be interesting for future studies to analyze the time period between formulation switching and excursions in trough levels, in order to ascertain whether excursions were a result of switching or were due to extrinsic factors.

While African-Americans typically require higher doses of tacrolimus to achieve target trough levels, it was interesting to note that the variable formulation group had a higher trough to dose ratio compared to the fixed formulation group, despite having a greater proportion of non-whites. We should also mention that the rate and extent of tacrolimus absorption are affected by the timing and content of meals and are greatest under fasted conditions. This is noteworthy in that we did not collect information about the timing of trough level measurements, which could have affected the interpretation of the trough to dose data.

While this study did not observe any differences in renal function or graft survival, it is important to note that it only included patients who had stable renal function and no episodes of rejection in the first 3 months post-transplantation. Patients receiving higher-risk donor kidneys or who experience rejection or delayed graft function post-transplantation may be at higher risk for adverse clinical outcomes than the patients captured in the present study.

As previously described, several studies have demonstrated that the use of generic tacrolimus is safe and bioequivalent to the innovator product [6,7,8]. Importantly, the recently published well-controlled bioequivalence crossover trial by Alloway et al. demonstrated the bioequivalency between the innovator tacrolimus formulation and two generic formulations as well as the bioequivalency between the two generic formulations [9]. Additionally, the US FDA analyzed the purity, potency, and quality of branded tacrolimus and available generic tacrolimus products using mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance, and bioactivity assay methods. The results demonstrated no discernable differences in the impurity profiles and potency between the generic and innovator products [13].

This study, however, sought to describe the extent of tacrolimus formulation switching post-transplantation and the subsequent consequences (i.e., frequency of therapeutic drug monitoring and excursions in trough concentrations), if any, of switching in a real-world setting. While this study did not meet the planned sample size because of the challenges in obtaining the NDC number for certain patients, the use of NDC numbers does, in fact, provide an accurate means to characterize specific formulations. Additionally, utilizing EMR-derived data holds promise as an efficient means to conduct retrospective observational studies. Despite these methodologic challenges, the study showed that 14.4% of stable kidney transplant patients received more than one tacrolimus formulation during the 1-year study period. Importantly, a variable tacrolimus regimen was associated with a higher frequency of trough concentration measurements and a greater number of excursions in trough levels compared with continuing on a fixed formulation.

This study had several limitations. As previously noted, study enrollment was limited by the challenges of obtaining NDC information on all patients in the post-transplant setting. This resulted in a relatively small sample size, which affected our ability to conduct some key analyses and limited the interpretability of the results. For example, the small sample size precluded an investigation of potential associations between the number of formulation changes and patient outcomes. The retrospective chart review design relied solely on the study sites’ ability to access the required data via their EMR system, which may have resulted in bias due to erroneous and missing data. A further study limitation is that the methodology did not allow examination of intra-patient variability in tacrolimus trough levels as a function of the time elapsed since NDC change. While this gives a real-world view of formulation switching in a clinically stable patient population, some patients may not have had stable tacrolimus levels prior to formulation switching, making associations between formulation switching and tacrolimus variability difficult to interpret. Despite these limitations, this study suggests that further evaluation is merited to assess the impact of using multiple tacrolimus formulations on long-term post-transplantation clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

This retrospective chart review study demonstrated the ability of using NDC numbers to collect precise information on the formulations patients use in a real-world setting. The study revealed that stable adult kidney transplant recipients receiving a variable tacrolimus formulation regimen had a higher frequency of trough level measurements and a greater number of excursions in trough levels compared with patients on a fixed formulation regimen of tacrolimus. Further evaluation is warranted to assess the impact of using multiple tacrolimus formulations on long-term post-transplantation clinical outcomes and healthcare utilization.

References

Peters DH, Fitton A, Plosker GL, Faulds D. Tacrolimus. A review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic potential in hepatic and renal transplantation. Drugs. 1933;46(4):746–94.

Molnar AO, Fergusson D, Tsampalieros AK, et al. Generic immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;350:h3163.

Rodrigo E, San D, Ruiz J, et al. High intra-patient variability in tacrolimus trough blood levels increases the risk of death-censored graft loss after kidney transplantation (abstract). Am J Transplant. 2015;15(Suppl 3). https://atcmeetingabstracts.com/abstract/high-intra-patient-variability-in-tacrolimus-trough-blood-levels-increases-the-risk-of-death-censored-graft-loss-after-kidney-transplantation/.

Klintmalm GB. Immunosuppression, generic drugs and the FDA. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(9):1765–6.

Trofe-Clark J, Gabardi S, McDevitt-Potter L, Alloway RR. Immunosuppression, generic drugs and the FDA. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(3):792–3.

McDevitt-Potter LM, Sadaka B, Tichy EM, Rogers CC, Gabardi S. A multicenter experience with generic tacrolimus conversion. Transplantation. 2011;92(6):653–7.

Momper JD, Ridenour TA, Schonder KS, Shapiro R, Humar A, Venkataramanan R. The impact of conversion from prograf to generic tacrolimus in liver and kidney transplant recipients with stable graft function. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(9):1861–7.

Spence MM, Nguyen LM, Hui RL, Chan J. Evaluation of clinical and safety outcomes associated with conversion from brand-name to generic tacrolimus in transplant recipients enrolled in an integrated health care system. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(11):981–7.

Alloway RR, Vinks AA, Fukuda T, et al. Bioequivalence between innovator and generic tacrolimus in liver and kidney transplant recipients: a randomized, crossover clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(11):e1002428.

Borra LC, Roodnat JI, Kal JA, Mathot RA, Weimar W, van Gelder T. High within-patient variability in the clearance of tacrolimus is a risk factor for poor long-term outcome after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(8):2757–63.

Marfo K, Aitken S, Akalin E. Clinical outcomes after conversion from brand-name tacrolimus (Prograf) to a generic formulation in renal transplant recipients: a retrospective cohort study. Pharm Ther. 2013;38(8):484–8.

Rosenborg S, Nordstrom A, Almquist T, Wennberg L, Barany P. Systematic conversion to generic tacrolimus in stable kidney transplant recipients. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(2):151–5.

Sommers CD, Pang ES, Ghasriani H, et al. Analyses of marketplace tacrolimus drug product quality: bioactivity, NMR and LC-MS. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2013;85:108–17.

Acknowledgements

Data analysis was conducted by CTI Clinical Trial and Consulting Services, Covington, KY. We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

This study, the article processing charges, and Open Access fee were sponsored by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc., Northbrook, IL. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Erin Baker, PhD, of CTI Clinical Trial and Consulting Services, Covington, KY. Support for this assistance was funded by Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

W. Irish, D. Facklam, and A. Butler: contributed to the design of the study, data analysis and interpretation, and authorship of the manuscript. J. Schwartz, E. Lee, B. Franks, J. Spalding, M. Vassilakis, and G. Thal contributed to the design of the study, data interpretation, and critical review of the manuscript.

Prior Presentation

This study was presented as a poster at ASN Kidney Week 2016, November 15–20, Chicago.

Disclosures

Jason Schwartz is an employee of Astellas and has received a salary from Astellas. Billy Franks is an employee of Astellas and has received a salary from Astellas. James Spalding is an employee of Astellas and has received a salary from Astellas. Maria Vassilakis is an employee of Astellas and has received a salary from Astellas. Gary Thal is an employee of Astellas and has received a salary from Astellas. Edward Lee is a former employee of Astellas and has received a salary from Astellas. Ashley Butler reports that CTI was contracted as a CRO for this study. David Facklam reports that CTI was contracted as a CRO for this study. William Irish reports that CTI was contracted as a CRO for this study.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with applicable policies and requirements from California Pacific Medical Center (Sutter Health IRB), Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland Clinic IRB), Lehigh Valley Hospital (Lehigh Valley Health Network IRB), Massachusetts General Hospital (Partners Human Research Committee), University of Utah (University of Utah IRB), and Washington University (Washington University Human Research Protection Office) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All sites submitted an informed consent waiver with IRB applications, as this study used de-identified patient data for a retrospective medical chart review.

Data Availability

Access to anonymized individual patient level data will not be provided for this trial as it meets one or more of the exceptions described under the Sponsor Specific Information for Astellas on www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7937948.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, J.J., Lee, E., Butler, A.P. et al. The Association of Tacrolimus Formulation Switching with Trough Concentration Variability: A Retrospective Cohort Study of Tacrolimus Use Post-Kidney Transplantation Based on National Drug Code (NDC) Numbers. Adv Ther 36, 1358–1369 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00950-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00950-5