Abstract

Colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R) gene mutations have been previously identified in chronic neutrophilic leukemia, atypical chronic myeloid leukemia, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, de novo acute myeloid leukemia, and severe congenital neutropenia, although there is limited data regarding lymphoid malignancies. Here, we present the first case of peripheral T cell lymphoma with CSF3R variant that developed persistent neutropenia in the follow-up visit and aplastic anemia after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on bone marrow aspiration (Qiagen clinical insight-QCI™). CSF3R single nucleotide variant (transcript variant 4), 46.0% (of 1081 reads) of variant allele fraction on exon 16 (lying to intronic region), nucleotide NM_172313.3, g36932463A > g, c.2041-35 T > C was identified by NGS. The case study presented here is an example of use of NGS in diagnosis, classification, prognostic or response indicator of hematologic malignancies, and identification of targeted therapy options in clinical practice. Additional work is needed to understand the clinical significance of this mutation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The peripheral T cell lymphoma (PTCL) corresponds to approximately 10% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. PTCL originates from mature T-cells and has heterogeneous features resulting in various morphologic subtypes. The most common subtype is PTCL-not otherwise specified (NOS) (26%), followed by angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma (nasal type), and subcutaneous panniculitis-like T cell lymphoma [1]. In terms of genetic features, PTCL generally has T cell receptor gene rearrangements, immunoglobulin germline mutations, chromosomal gains (7q, 8q, 17q, 22q), and chromosomal losses (4q, 5q, 6q, 9p, 10q, 12q, 13q). Gene expression profiling (GEP) studies have introduced two molecular subgroups of PTCL-NOS. These subgroups are high expression of transcription factors TBX-21 and GATA-3, and they are associated with differentiation of CD4 + T cells into Th1 and 2 [2, 3].

Colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (CSF3R) gene encodes the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor (G-CSFR, CD114) which is fundamental for binding G-CSF and provides subsequently granulocyte proliferation, differentiation and survival. The localization of gene on chromosome 1 was established by hybridization and polymerase chain reaction methods. CSF3R consists of an Ig-like domain, a cytokine receptor homologous domain, 3 fibronectin type III domains, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic region and contains 17 exons [4].

Acquired nonsense and frameshift truncation variants in the cytoplasmic domain and activating missense variants in the membrane proximal region of CSF3R have been frequently observed in chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) and rarely observed in atypical chronic myeloid leukemia (aCML), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) and de novo acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Germline homozygous and compound heterozygous nonsense and frameshift truncating variants in the extracellular domain of CSF3R and acquired cytoplasmic truncating CSF3R variants have been observed in severe congenital neutropenia (SCN) [5,6,7,8]. Furthermore, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and multiple myeloma cases with CSF3R mutation or variants have been recently observed [9, 10]. Significance of heterozygous germ line variants is unknown [9]. The association of CSF3R mutations/variants and lymphoid malignancies is limited even in T cell lymphoid malignancies. We have seen one case that was diagnosed with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma a concomitant CSF3R germline variant [11]. Here, we report the first case with cytopenia and relapsing febrile neutropenia during lymphoma treatment that resulted in aplastic anemia after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation co-occurrence peripheral T cell lymphoma and CSF3R variant in exon 16 at diagnosis.

Clinical history

A 69-year-old woman arrived at the hospital with anemia, leukopenia, and cervical and abdominal lymphadenopathies. The patient had mild leukopenia, moderate anemia, and multiple lymphadenopathies, liver-spleen-diffuse bone involvements in PET/CT scans. The patient was diagnosed with CD30 ( +) peripheral T cell lymphoma, NOS by axillary lymph node (Fig. 1A, B, C and D) and bone marrow biopsies via morphology and immunhistochemistry examination (Fig. 1E, F, G, and H). She had stage IVEB disease and International Prognostic Index (IPI) was 4. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP protocol) and entecavir due to hepatitis serology was initiated to the patient. During the treatment in every cycle, she had grade 2/3 febrile neutropenia without any proven origin of infection and needed broad-spectrum antibiotics and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) support. She was responsive to G-CSF administrations.

Material and methods

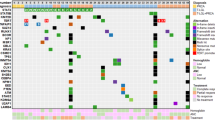

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed on somatic panel which consists of ASXL1, CALR, CBL, CEBPA, CSF3R, DNMT3A, EZH2, FLT3, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KIT, KRAS, MPL, NPM1, NRAS, RUNX1, SETBP1, SF3B1, SH2B3, SRSF2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, and ZRSR2 from bone marrow aspiration sample (Qiagen clinical insight-QCI™). Clinical significance of variants were interpreted as tier 1A and 1B, strong significance; tier 2C and 2D, potential significance, and tier 3, uncertain significance based on guidelines.

Results

In the genetic analysis, CSF3R single nucleotide variant (transcript variant 4), 46.0% (of 1081 reads) of variant allele fraction on exon 16 (lying to intronic region), nucleotide NM_172313.3, g36932463A > g, and c.2041-35 T > C was identified by NGS from bone marrow aspiration sample and was interpreted as tier 3 uncertain significance according to database (Qiagen clinical insight-QCI™). After favorable interim assessment, 6 courses of CHOP was completed and remission was achieved. The patient had autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) without any complications. Neutrophil and thrombocyte (> 20.000/mm3) engraftment occurred in the fourth week after the transplant and eltrombopag treatment started. Initially the response to eltrombopag was favorable. However, in the follow-up, the patient’s thrombocyte count started to drop. On the 100th day assessment, relapse was demonstrated with PET/CT scans and bone marrow biopsy. Afterwards, brentixumab and bendamustine treatment was initiated. The patient also had febrile neutropenia periods during the chemotherapy protocols which were responsive to antibiotherapy and G-CSF. She was admitted to hospital with febrile neutropenia after the third chemotherapy protocol, at which point pneumonia, pyelonephritis and pancytopenia were observed and broad-spectrum antibiotics and G-CSF treatments started. Cytopenia was attributed to primary disease infiltration, peripheral destruction and bone marrow suppression due to severe infection status. However, the patient did not respond to the antibiotic treatment, G-CSF, and blood transfusion support and deceased in the intensive care unit (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In recent years, use of NGS has been spreading. NGS has been especially useful in classification, diagnosis, prognostic indicator, and assessment of minimal residual disease of hematologic malignancies and targeted therapy options in clinical practice. However, these results may be confusing and may possess uncertain clinical significance in certain cases.

CSF3 and CSF3R are fundamental for production and proliferation of neutrophils. CSF3R mutations were observed in CNL, SCN, SCN-AML, de novo or secondary AML and limited B lymphoid malignancies such as B-ALL and multiple myeloma. As far as a germline mutation of CSF3R is concerned, we have encountered only one cutaneous T-cell lymphoma case in the literature [11]. There was no peripheral T-cell lymphoma report with this mutation/variant and consequently we initiated CHOP protocol for peripheral T-cell lymphoma. However, during the CHOP treatment, the patient (who had not have history of neutropenia or cytopenia and family history regarding cytopenia) had febrile neutropenia and needed broad-spectrum antibiotics and G-CSF support. The patient’s recovery from ASCT procedure occurred unexpectedly, and neutrophil and thrombocyte levels stayed under the targeted levels and continued in the follow up visits, similarly. After relapse, we tried to treat infection and cytopenia with the salvage chemotherapy. Ultimately, she deceased due to infection and cytopenia in the status of dependence of blood transfusion and G-CSF support.

At the beginning, CSF3R variant was not considered to be of importance due to mentioned tier 3 uncertain significance who was diagnosed with PTCL. However, we reevaluated the patient’s clinical history again due to the poor patient outcome. The patient’s family was questioned about the patient’s medical history and family history, especially her children’s medical status due to possibility of having germline (46% of variant allelic fraction) of this variant which can develop neutropenia. There was no finding of neutropenia in the patient and patient’s family. Because of no family history especially in her children and the possibility of being recessive, we did not analyze her children regarding this variant. We also could not obtain a sample from patient for verification of germline possibility due to death. We observed the ever-increasing rate of lipocytes and decreasing the cellularity in the bone marrow. Lipocyte/cellularity rate was 40/60, 60/40, and 90/10, at the diagnosis, before the transplant and first relapse, respectively. When lipocyte/cellularity rate was 90/10 in the bone marrow biopsy, WBC count was 2600/mm3, neutrophil count was 700/mm3, hemoglobin level was 9.6 g/dL, platelet count was 16.000/mm3 and corrected reticulocyte count was 0.9%. These results were indicative of severe aplastic anemia.

As a summary, we encountered a patient who was diagnosed with PTCL concomitant CSF3R variant and developed severe neutropenia and aplasia compatible with aplastic anemia. Aplastic anemia (AA) is a disease of bone marrow failure associated with hypoplasia or aplasia due to inherited/genetic disorders or acquired factors such as immune disorders, drugs, toxic chemicals, viral infections [12]. AA has a high morbidity and mortality rate, with severe form of the disease having approximately 70% mortality risk in 2 years if the disease was not treated optimally. Somatic mutation rate is between 5 and 70% in the studies while germline mutations are establishing more frequent recently. In AA DNMT3A, BCOR, BCORL1, and ASXL1 can be detected in the molecular analysis [13,14,15].

We reviewed the literature regarding nucleotide NM_172313.3 mutation/variant and co-morbidity peripheral T cell lymphoma, neutropenia, and/or aplastic anemia. We have not found any work concerning the identical circumstance due to identified NM_172313.3:g36932463A > g, c.2041-35 T > C, and non-protein coding. We also searched the databases such as ClinVar (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar), refSeq (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/RefSeq), dbSNP (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbSNP), MedGen (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/MedGen), and OMIM (www.omim.org) and have found no identical case. Hence, this is the first patient who is presented with CSF3R variant with NM_172313.3:g36932463A > g, c.2041-35 T > C up to date.

In this case, the first challenge is where to locate this variant in the clinical range. There are also unanswered questions, e.g., this mutation could be associated with aplastic anemia or peripheral T cell lymphoma or isolated neutropenia, could CSF3R mutation be an indicator of aplastic anemia, did intensive and conditioning chemotherapies and ASCT accelerate this aplasia process, should we approach to such cases more nonintensive or use prophylaxis due to susceptible to be neutropenic and severe infections during chemotherapy, could CSF3R be a targeted therapy option in the future. Literature needs to be clarified regarding NGS and challenges of interpretations. We think additional studies and reports are needed to reach a more accurate conclusion.

References

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris NL, Stein H, Siebert R et al (2016) The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood 127:2375

Wang T, Feldman AL, Wada DA, Lu Y, Polk A, Briski R et al (2014) GATA-3 expression identifies a high risk subset of PTCL, NOS with distinct molecular and clinical features. Blood 123:3007

Heavican TB, Bouska A, Yu J, Lone W, Amador C, Gong Q et al (2019) Genetic drivers of oncogenic pathways in molecular subgroups of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Blood 133:1664

Seto Y, Fukunaga R, Nagata S (1992) Chromosomal gene organization of the human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor. J Immun 148:259–266

Maxson JE, Gotlib J, Pollyea DA, Fleischman AG, Agarwal A, Eida CA et al (2013) Oncogenic CSF3R mutations in chronic neutrophilic leukemia and atypical CML. N Engl J Med 368(19):1781–1790

Zhang H, Wilmot B, Bottomly D, Dao KHT, Stevens E, Eide CA et al (2019) Genomic landscape of neutrophilic leukemias of ambiguous diagnosis. Blood 134(11):867–879

Triot A, Jarvinen PM, Arostegui JI, Murugan D, Kohistani N, Diaz JLD et al (2014) Inherited biallelic CSF3R mutations in severe congenital neutropenia. Blood 123(24):3811–3817

Cassinat B, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Notz-Carrere A, Lenot ML, Vaury C, Micheau M et al (2004) Screening for G-CSF receptor mutations in patients with secondary myeloid or lymphoid transformation of severe congenital neutropenia. A report from the French neutropenia register. Leukemia 18(9):1553–1555.

Trottier AM, Druhan LJ, Kraft IL, Lance A, Feurstein S, Helgeson M et al (2020) Heterozygous germ line CSF3R variants as risk alleles for development of hematologic malignancies. Blood adv 4(20):5269–5284

Schwartz MS, Wieduwilt MJ (2020) CSF3R truncation mutations in a patient with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a favorable response to chemotherapy plus dasatinib. Leuk Res Rep 14:100208

Scott AJ, Tokaz MC, Jacobs MF, Chinnaiyan AM, Phillips TJ, Wilcox RA (2021) Germline variants discovered in lymphoma patients undergoing tumor profiling: a case series. Fam Cancer 20(1):61–65

Young NS, Scheinberg P, Calado RT (2008) Aplastic anemia. Curr Opin Hematol 15(3):162–168

Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, Makishima H, Yoshida K, Townsley D et al (2015) Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med 373(1):35–47

Lane AA, Odejide O, Kopp N, Kim S, Yoda A, Erlich R et al (2013) Low frequency clonal mutations recoverable by deep sequencing in patients with aplastic anemia. Leukemia 27(4):968–971

Malcovati L, Galli A, Travaglino E, Ambaglio I, Rizzo E, Molteni E et al (2017) Clinical significance of somatic mutation in unexplained blood cytopenia. Blood 129(25):3371–3378

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed significantly. All authors are in agreement with the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate/informed consent

Obtained from patient legal representative.

Consent for publication

Obtained from patient legal representative.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kirkizlar, O., Can, N. The first case of peripheral T cell lyphoma with a CSF3R variant resulted in relapsing febrile neutropenia and aplastic anemia. J Hematopathol 15, 245–248 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-022-00513-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-022-00513-8