Abstract

Epidemiology of lymphoma is not well described in Mexico. We determined the frequencies and subtypes of the main non-Hodgkin’s and Hodgkin’s lymphomas in the Mexican population. Files for tissue samples for lymphomas stored in five different hospitals in Mexico City were retrieved for re-analysis and further immunostaining. The most common mature B cell, T cell/NK cell, Hodgkin’s, and precursor lymphoid neoplasms were identified according to the 2008 WHO classification of tumors. All stains were performed in the same laboratory and interpreted by three pathologists. Five thousand seven hundred seventy-two neoplasms were included. Of these, 4213 were mature B cell neoplasms (73%; 95% CI 71.83–74.12), 888 Hodgkin’s lymphomas (HLs) (15%; 95% CI 14.48–16.34), 496 mature T cell/NK neoplasms (9%; 95% CI 7.89–9.34), and 175 precursor lymphoid neoplasms (3%; 95% CI 2.62–3.5). Neoplasms had an even distribution between sexes. Main mature B cell lymphomas were diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (56%; 95% CI 54.39–57.39) and follicular lymphoma (FL) (20%; 95% CI 18.92–21.34). Hodgkin’s lymphomas were also classified into five main subtypes, with nodular sclerosis (47%; 95% CI 44.14–50.7) and mixed cellularity (38%; 95% CI 34.49–40.85) being the most common. The most common mature T cell/NK neoplasm was peripheral T cell lymphoma NOS/anaplastic large cell lymphoma ALK negative (44%; 95% CI 39.85–48.84). This is the first descriptive study in Mexico with a large sample of lymphomas classified according to the 2008 WHO classification. The results obtained are in keeping with the numbers described in other populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the USA and one of the three most common causes in higher income countries. Lymphomas, including both Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), are the sixth most common neoplasms in the USA, constituting 4.8% of all new cancers each year and 3.5% of yearly cancer deaths [1, 2]. Mexico is in epidemiologic transition, meaning that chronic-degenerative diseases and cancer are increasingly gaining importance with decreasing mortality of infectious diseases [3]. The recorded mortality rate in Mexico due to neoplastic diseases more than doubled between the years of 1955 and 2002, increasing from 28.1 to 57.2 cases per 100,000 individuals [4]. As of 2013, cancer became the third leading cause of death in Mexico [5].

In Latin America, NHLs are listed by the WHO as the eighth most common malignancy [6]. In Mexico, the latest registry of malignant neoplasms was completed in 2002. It listed lymphoma and leukemia among the 15th most frequent neoplasms constituting 8.2% of the total cancers. Unfortunately, accurate and up to date registries are lacking and an effort to improve this area of epidemiology in Mexico is important [4].

The World Health Organization (WHO) updated in 2017 the classification system for hematopoietic and lymphoid tissue tumors. The previous classification and fourth edition were published in 2008 and both serve as worldwide guidelines and consensus definitions to the different hematological malignancies. These are based on the revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms (REAL) proposed by the International Lymphoma Study Group (ILSG) [7, 8]. They are relevant to provide context and appropriate organization for epidemiologic, management, and future research. The 2008 and the updated 2017 WHO classifications consider each type of lymphoma as a unique entity which is defined by its morphology, immunophenotype, clinical findings, and cytogenetic abnormalities. Pathologists are advised to use this system in daily practice and be aware that the lymphoid neoplasms must be analyzed based not only on morphology but also on immunophenotype at a minimum, to reach an accurate diagnosis.

The epidemiology and distribution of lymphoma subtypes are well known in higher income countries [1, 9, 10]; however, in Mexico, the data is limited and dated and has several methodological limitations [11,12,13,14,15]. Thus, this study aimed to provide updated information about the epidemiology of lymphomas in Mexico from five high-volume referral centers, and report on their morphology and immunophenotype based on the 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid tissues.

Methods

Files from the period between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2014, for consecutive tissue samples with a diagnosis of lymphoma that were stored in five different hospitals in Mexico City (Hospital Español de México, Hospital Ángeles del Pedregal, Hospital Ángeles de las Lomas, Centro Médico Nacional La Raza, and Laboratorio de Patología, Inmunohistoquímica y Citopatología, SC (PIC)) were retrieved for re-analysis. Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) was used for the documentation of demographic data (i.e., age and sex) as well as for statistical analysis.

All the cases that had tissue sections available from storage in paraffin blocks were cut at a width of 2 to 3 μm and were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The biopsies were processed according to local protocols in the participating laboratories and were fixed in 10% formalin buffer for 6 to 48 h. Specific immunostaining (Table 1) was performed for the different diagnostic possibilities including diffuse large B cell lymphomas (DLBCL), small B cell lymphomas (SBCL), B cell lymphomas with plasmacytoid differentiation, Hodgkin’s lymphomas, and mature T/NK cell lymphomas. Immunostaining for all cases was completed in one laboratory (PIC) and interpreted by the same three pathologists. Diagnoses of precursor B cell lymphomas were excluded from further characterization. Hematopoietic neoplasia with null immunophenotype and plasma cell neoplasms were excluded from our analysis. Lymphomas were classified based on the morphological and immunophenotypic criteria specified by the 2008 WHO criteria [8] as provided by the three participating pathologists. Data is presented using simple proportions and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the Wilson score method [16].

Results

We included 5772 lymphoid neoplasms from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2014, in this study. Of these, 4213 were classified as mature B cell neoplasms (73%; 95% CI 71.83–74.12), 888 as Hodgkin’s lymphomas (15%; 95% CI 14.48–16.34), 496 as mature T cell/NK neoplasms (9%; 95% CI 7.89–9.34), and 175 as precursor lymphoid neoplasms (3%; 95% CI 2.62–3.5) (Table 2). An even distribution between sexes was observed throughout the different neoplasms, with 51% of the cases being male patients. Figure 1 summarizes the distribution of lymphoma cases in Mexico.

All four different categories of neoplasms were further analyzed and classified according to the 2008 WHO classification as specified in the “Methods” section. Six mature B cell lymphomas accounted for almost 95% of all B cell neoplasms. These included diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (56%; 95% CI 54.39–57.39), follicular lymphoma (FL) (20%; 95% CI 18.92–21.34), mantle cell lymphoma (6.7%; 95% CI 6.02–7.53), marginal zone/MALT lymphoma (5.2%; 95% CI 4.59–5.93), chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (4.6%; 95% CI 4.01–5.28), and Burkitt’s lymphoma (2.5%; 95% CI 2.04–2.98) (Table 2). Other B cell neoplasms accounting for almost 5% of the cohort were identified but consisted individually in less than 1.4% of the total cases. These included hairy cell leukemia, lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia, splenic B cell lymphoma, and unclassifiable B cell lymphoma with features intermediate between DLBCL and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Hodgkin’s lymphomas were also classified into the five main subtypes, with nodular sclerosis (47%; 95% CI 44.14–50.7) and mixed cellularity (38%; 95% CI 34.49–40.85) being the most common and accounting for 85% of all HL cases (Table 2). Lymphocyte depleted, lymphocyte rich, nodular lymphocyte predominant, and unclassifiable classical HL contributed each with less than 7% of the cases.

Several mature T cells/NK neoplasms were identified, with the majority of cases being peripheral T cell lymphoma NOS/anaplastic large cell lymphoma ALK negative (44%; 95% CI 39.85–48.84) and extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type (30%; 95% CI 25.5–33.76) (Table 2). Other identified lymphomas included ALK-positive anaplastic lymphoma, mycosis fungoides, and angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Again, about 5% of the total T cell lymphomas were accounted by rare lymphomas presenting with 9 or fewer cases in the cohort and including primary cutaneous gamma-delta T cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous CD8- or CD4-positive T cell lymphoma, and hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma.

Analysis of the cases by group age was also performed for mature B cell neoplasms and HL. Patients were classified into different age categories in intervals of 20 years. Figure 2 shows a graph comparing distribution in age groups for the main B cell neoplasms. The majority of the B cell neoplasms occurred in the age group between 61 and 80 years old, followed by the group between 41 and 60 years old. This applied also to the 2 most common B cell malignancies, DLBCL and follicular lymphoma. Eight hundred sixty-five (36.7%) cases of DLBCL were identified in the group between 61 and 80 years old and 660 (28%) in the 41–60 years old group. For follicular lymphoma, 309 (36.5%) cases were in the 41–60 years old age group and 274 (32.3%) in the 61–80 years old group. Burkitt’s lymphoma occurred evenly throughout age groups 2–20, 21–40, and 41–60 years old with an average of 25 cases per group.

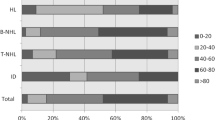

In the case of HL, the majority of nodular sclerosis subtypes were seen in the group age of 21–40 years old with 175 (41.6%) cases. Eighty-one (19.2%) cases were observed in the 2–20 years old group, although the majority was closer to 19 years of age. Sixty-one (14.5%) cases occurred in the 41–60 age group, with most of the cases presenting in the late 50’s. Mixed cellularity subtype showed a more even distribution in the age groups between 21 and 80 years old. Eighty-seven (26%) cases were identified in the 21–40 years old age group. The rest of HL subtypes also had an even distribution between age groups. Figure 3 shows more details related to age distribution in HL.

Discussion

The incidence of lymphoma continues to increase in Mexico, with various factors playing a role on it including improvements in detection systems, increase in the population’s life expectancy, chronic viral and bacterial infections, exposure to chemical products as benzene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, pesticides, and ionizing radiation [17, 18], genetic factors, and probably ethnicity [19]. However, no accurate data exist in the distribution of the different lymphoma types. This is the first descriptive study with a large sample of confirmed lymphoid neoplasms, using a standardized method of staining, classified according to the 2008 WHO classification of tumors representative of the Mexican population. It serves as a complement to the current epidemiologic registry of neoplasms in Mexico, adding classification details according to global standards set by the WHO. Our study showed a distribution of about 85% NHLs and 15% HLs. Eighty-six percent of the NHLs corresponded to B cell neoplasms, with the rest being T cell lymphomas. This is consistent with similar series published for Latin America [20] and the world [21, 22].

Unfortunately, until today, a complete histopathologic record of lymphoid malignancies with accurate classification according to WHO criteria does not exist in Mexico [23]. In the present study, we observed consistency and certain differences throughout our results with the prevalence of lymphomas reported in other areas of the world. For example, all grades of follicular lymphoma comprised 20.1% of our B cell lymphomas, comparable with values reported for Central and South America but lower than the 33.8% for North America [20] and higher than the 15.9% for Western Europe [17]. DLBCL accounted for 55.9% of B cell neoplasms in our series, being slightly higher than the average 40% reported for Central and South America and the WHO’s 42%, but consistent with Peru’s average [20]. A possible explanation of the higher frequencies of DLBCL in Mexico is the late presentation and search of medical attention by some patients due to low education and socioeconomic status. This allows for low-grade lymphomas to progress and transform into aggressive lymphomas without a diagnosis being made prior to the development of significant symptomatology [24,25,26].

Histopathologic diagnosis of T cell lymphomas is complex and requires a greater number of antibodies as compared to B cell lymphomas [27]. Our series reports T cell lymphomas comprising around 10% of NHLs, again consistent with what has been observed in Central and South America [20]. It is known that T cell neoplasms vary from geographical area to another, with Japan for example reporting them as up to 18% of their NHLs [28, 29]. Most of our cases (44.3%) are peripheral T cell lymphomas NOS. It is possible that this group is overrepresented as some of the subclassifications of T cell neoplasms were unable to be tested for due to economical limitations. As such, some lymphomas were classified as peripheral T cell lymphomas NOS but may have belonged to another category if further testing could have been performed. A high number (29.5%) of extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type was observed. Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma nasal type is more common in Asia and is associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [30]. In our series, it represents 2.8% of the NHLs, showing a relatively higher incidence than other areas in the world but consistent with reports from other areas of Latin America like Peru and Chile [20, 31].

Hodgkin’s lymphoma represented 15% of our series. Nodular sclerosis subtype was the most common comprising 47% of the HL cases and 7.33% of the series. Most of the remaining cases (38%) were of the mixed cellularity subtype. Nodular lymphocyte predominant comprised 4% of our HL cases. This pattern of predominance, where classical HL conforms the majority and nodular lymphocyte predominant conforms only a minority and usually less than 10% of all HL, is widely observed in the world [7]. The distribution of HL in Mexico followed the usual pattern reported in other series in North America [32,33,34,35].

Our study has strengths and limitations. The hospitals involved in providing the data are referral centers for a heterogeneous group of patients from all the Mexican regions. The participating hospitals have distinct population catchment areas, providing a varied socioeconomic and ethnic background to our study. This selection of hospitals provides us with an appropriate cohort of cases required to represent a diverse Mexican population [36]. However, none of the institutions involved in our series are reference centers for pediatric cases, so the population between 2 and 20 years old is most likely underrepresented. Our goal was to provide a distribution of lymphomas mainly in adult population.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest series and the first descriptive study of its kind in Mexico studying and analyzing the frequency of lymphoid neoplasms using a consistent and standardized morphological and immunohistochemical approach. The results obtained are in keeping with the numbers described in other population studies worldwide. This study offers an emphasis on the correct classification of these neoplasms based on internationally accepted criteria. It does not intend to replace formal epidemiological records of lymphoid neoplasms in Mexico but it should complement existent epidemiological information.

References

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma - Cancer Stat Facts 2018. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/nhl.html

Hodgkin lymphoma - Cancer Stat Facts 2018. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/hodg.html

Meneses-García A, Ruiz-Godoy LM, Beltrán-Ortega A, Sánchez-Cervantes F, Tapia-Conyer R, Mohar A (2012) Main malignant neoplasms in Mexico and their geographic distribution, 1993-2002. Rev Investig Clin 64(4):322–329

Benitez-Aranda H (2002) Epidemiologia de las enfermedades hematologicas en el ambito nacional. Gac Med Mex 138(2):S12–SS8

Soto-Estrada G, Moreno-Altamirano L, Palma-Diaz D (2016) Panorama epidemiologico de Mexico, principales causas de morbilidad y mortalidad. Rev Fac Med UNAM 59(6):8–22

Cancer today 2018. Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home

Swerdlow SH, World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer (2017) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon 585 pages

Swerdlow SH, International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization (2008) WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 4th edn. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon 439 p

Morton LM, Slager SL, Cerhan JR, Wang SS, Vajdic CM, Skibola CF, Bracci PM, de Sanjose S, Smedby KE, Chiu BCH, Zhang Y, Mbulaiteye SM, Monnereau A, Turner JJ, Clavel J, Adami HO, Chang ET, Glimelius B, Hjalgrim H, Melbye M, Crosignani P, di Lollo S, Miligi L, Nanni O, Ramazzotti V, Rodella S, Costantini AS, Stagnaro E, Tumino R, Vindigni C, Vineis P, Becker N, Benavente Y, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Cocco P, Foretova L, Maynadie M, Nieters A, Staines A, Colt JS, Cozen W, Davis S, de Roos AJ, Hartge P, Rothman N, Severson RK, Holly EA, Call TG, Feldman AL, Habermann TM, Liebow M, Blair A, Cantor KP, Kane EV, Lightfoot T, Roman E, Smith A, Brooks-Wilson A, Connors JM, Gascoyne RD, Spinelli JJ, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, Holford TR, Lan Q, Zheng T, Orsi L, Dal Maso L, Franceschi S, la Vecchia C, Negri E, Serraino D, Bernstein L, Levine A, Friedberg JW, Kelly JL, Berndt SI, Birmann BM, Clarke CA, Flowers CR, Foran JM, Kadin ME, Paltiel O, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS, Sampson JN (2014) Etiologic heterogeneity among non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: the InterLymph Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Subtypes Project. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2014(48):130–144

Huh J (2012) Epidemiologic overview of malignant lymphoma. Korean J Hematol 47(2):92–104

Mendoza-Sanchez HF, Quintana-Sanchez JA, Rivera-Marquez H, Mejia-Dominguez AM, Fajardo-Gutierrez A (1998) Epidemiology of lymphomas in children residing in Mexico City. Arch Med Res 29(1):67–73

Ortega V, Verastegui E, Flores G, Meneses A, Ocadiz R, Alfaro G (1998) Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas in Mexico. A clinicopathological and molecular analysis. Leuk Lymphoma 31(5–6):575–582

Rendon-Macias ME, Valencia-Ramon EA, Fajardo-Gutierrez A, Rivera-Flores E (2015) Childhood lymphoma incidence patterns by ICCC-3 subtype in Mexico City metropolitan area population insured by Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 1996-2010. Cancer Causes Control 26(6):849–857

Ron-Guerrero CR-MA, Medina-Palacios CL, Lopez-Flores F (2015) Epidemiologia de los linfomas del Centro Estatal de Cancerologia de Nayarit. Rev Hematol Mex 16:109–114

Rivera-Luna R, Shalkow-Klincovstein J, Velasco-Hidalgo L, Cardenas-Cardos R, Zapata-Tarres M, Olaya-Vargas A et al (2014) Descriptive epidemiology in Mexican children with cancer under an open national public health insurance program. BMC Cancer 14:790

Newcombe RG (1998) Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med 17(8):857–872

Ambinder AJ, Shenoy PJ, Malik N, Maggioncalda A, Nastoupil LJ, Flowers CR (2012) Exploring risk factors for follicular lymphoma. Adv Hematol 2012:626–635

Fisher SG, Fisher RI (2004) The epidemiology of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Oncogene 23(38):6524–6534

Cerhan JR, Slager SL (2015) Familial predisposition and genetic risk factors for lymphoma. Blood 126(20):2265–2273

Laurini JA, Perry AM, Boilesen E, Diebold J, Maclennan KA, Muller-Hermelink HK et al (2012) Classification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Central and South America: a review of 1028 cases. Blood 120(24):4795–4801

Novelli S, Briones J, Sierra J (2013) Epidemiology of lymphoid malignancies: last decade update. Springerplus 2(1):70

Roman E, Smith AG (2011) Epidemiology of lymphomas. Histopathology 58(1):4–14

Tirado-Gómez L, Mohar-Betancourt A (2007) Epidemiología de las Neoplasias Hemato-Oncológicas. Cancerología 2:109–120

Smith A, Crouch S, Howell D, Burton C, Patmore R, Roman E (2015) Impact of age and socioeconomic status on treatment and survival from aggressive lymphoma: a UK population-based study of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol 39(6):1103–1112

Tadmor T, Shvidel L, Bairey O, Goldschmidt N, Ruchlemer R, Fineman R, Rahimi-Levene N, Herishanu Y, Yuklea M, Arad A, Aviv A, Polliack A, On behalf of the Israeli CLL Study Group (2014) Richter’s transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective study reporting clinical data, outcome, and the benefit of adding rituximab to chemotherapy, from the Israeli CLL Study Group. Am J Hematol 89(11):E218–E222

Lossos IS, Gascoyne RD (2011) Transformation of follicular lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 24(2):147–163

Warnke RA, Jones D, Hsi ED (2007) Morphologic and immunophenotypic variants of nodal T-cell lymphomas and T-cell lymphoma mimics. Am J Clin Pathol 127(4):511–527

Perry AM, Diebold J, Nathwani BN, MacLennan KA, Muller-Hermelink HK, Bast M et al (2016) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the Far East: review of 730 cases from the international non-Hodgkin lymphoma classification project. Ann Hematol 95(2):245–251

Yamaguchi K, Takatsuki K (1993) Adult T cell leukaemia-lymphoma. Baillieres Clin Haematol 6(4):899–915

Jhuang JY, Chang ST, Weng SF, Pan ST, Chu PY, Hsieh PP, Wei CH, Chou SC, Koo CL, Chen CJ, Hsu JD, Chuang SS (2015) Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type in Taiwan: a relatively higher frequency of T-cell lineage and poor survival for extranasal tumors. Hum Pathol 46(2):313–321

Cabrera ME, Martinez V, Nathwani BN, Muller-Hermelink HK, Diebold J, Maclennan KA et al (2012) Non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Chile: a review of 207 consecutive adult cases by a panel of five expert hematopathologists. Leuk Lymphoma 53(7):1311–1317

Laurent C, Do C, Gourraud PA, de Paiva GR, Valmary S, Brousset P (2015) Prevalence of common non-Hodgkin lymphomas and subtypes of Hodgkin lymphoma by nodal site of involvement: a systematic retrospective review of 938 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 94(25):e987

Salati M, Cesaretti M, Macchia M, Mistiri ME, Federico M (2014) Epidemiological overview of Hodgkin lymphoma across the Mediterranean Basin. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 6(1):2014048

Thomas RK, Re D, Zander T, Wolf J, Diehl V (2002) Epidemiology and etiology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol 13(Suppl 4):147–152

Hodgkin lymphoma incidence statistics 2015 [updated 2015-05-15. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/hodgkin-lymphoma/incidence

Moreno-Estrada A, Gignoux CR, Fernandez-Lopez JC, Zakharia F, Sikora M, Contreras AV, Acuna-Alonzo V, Sandoval K, Eng C, Romero-Hidalgo S, Ortiz-Tello P, Robles V, Kenny EE, Nuno-Arana I, Barquera-Lozano R, Macin-Perez G, Granados-Arriola J, Huntsman S, Galanter JM, Via M, Ford JG, Chapela R, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Rodriguez-Santana JR, Romieu I, Sienra-Monge JJ, Navarro BR, London SJ, Ruiz-Linares A, Garcia-Herrera R, Estrada K, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Jimenez-Sanchez G, Carnevale A, Soberon X, Canizales-Quinteros S, Rangel-Villalobos H, Silva-Zolezzi I, Burchard EG, Bustamante CD (2014) Human genetics. The genetics of Mexico recapitulates Native American substructure and affects biomedical traits. Science 344(6189):1280–1285

Authorship

AC-Z, AG-H, LP-B, PR-S, RS-V-L, JV-T, and LM-H abstracted the data. AG-H and AC-Z analyzed the data. AZ-O and AL-L conceived the study. AG-H, AC-Z, and AL-L drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version. All persons who contributed significantly to this work have been acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carballo-Zarate, A., Garcia-Horton, A., Palma-Berre, L. et al. Distribution of lymphomas in Mexico: a multicenter descriptive study. J Hematopathol 11, 99–105 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-018-0336-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-018-0336-0