Abstract

Alongside citizens’ belief in the legitimacy of democracy, public support for the political regime is crucial to the survival of (democratic) political systems. Yet, we know fairly little about the relationship between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their evaluation of democratic performance from a global comparative perspective. In this article, we argue that the cognitive ability of citizens to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian characteristics constitutes the individual yardstick for assessing democracy in practice. Furthermore, we expect that the effect of citizens’ democratic knowledge on their evaluation of democratic performance is moderated by the institutional level of democracy. We test these assumptions by combining data from the sixth and seventh wave of the World Values Survey and the third pre-release of the European Values Study 2017, resulting in 114 representative samples from 80 countries with 128,127 respondents. Applying multilevel regression modeling, we find that the higher a country’s level of democracy, the more positive the effect of democratic knowledge on citizens’ assessment of democratic performance. In contrast, we find that the lower the level of democracy in a country, the more negative the effect of citizens’ democratic knowledge on their evaluation of democracy. Thus, this study shows that citizens who are more knowledgeable about democracy are most cognitively able to assess the level of democracy in line with country-level measures of democracy. These results open up new theoretical and empirical perspectives for related research on support for and satisfaction with democracy as well as research on democratization.

Zusammenfassung

Die zentralen Werte und Normen, die das Überleben eines (demokratischen) politischen Systems sichern, sind neben dem Glauben der Bürgerinnen und Bürger an die Legitimität der Demokratie ihre öffentliche Unterstützung für das politische Regime. Allerdings wissen wir aus einer vergleichenden globalen Perspektive noch recht wenig über die Beziehung zwischen dem demokratischen Wissen der Bürgerinnen und Bürger und ihrer Einschätzung der demokratischen Performanz. In diesem Artikel argumentieren wir, dass die kognitive Fähigkeit der Bürgerinnen und Bürger, zwischen demokratischen und autoritären Merkmalen zu unterscheiden, den individuellen Maßstab für die Beurteilung der Demokratie in der Praxis darstellt. Wir erwarten zudem, dass der Effekt des demokratischen Wissens der Bürgerinnen und Bürger hinsichtlich ihrer Bewertung der demokratischen Performanz durch das institutionelle Niveau der Demokratie moderiert wird. Wir testen diese Annahmen unter Verwendung von Individualdaten aus der sechsten und siebten Welle des World Values Survey und des dritten pre-release der European Values Study 2017, woraus 114 repräsentative Stichproben aus 80 Ländern mit insgesamt 128.127 Befragten resultieren. Basierend auf der Anwendung von Mehrebenenmodellen kommen wir zu dem Ergebnis, dass der Einfluss des demokratischen Wissens auf die Bewertung der demokratischen Performanz durch die Bürgerinnen und Bürger umso positiver ist, je höher das Niveau der Demokratie eines Landes ist. Im Gegensatz dazu stellen wir fest, dass sich das demokratische Wissen der Bürgerinnen und Bürger umso negativer auf ihre Einschätzung der Demokratie auswirkt, je niedriger das Niveau der Demokratie in einem Land ist. Mit dieser Studie zeigen wir folglich, dass Bürgerinnen und Bürger, die über mehr Wissen über die Demokratie verfügen, kognitiv am ehesten in der Lage sind, das Niveau der Demokratie in Übereinstimmung mit Bewertungen der Demokratie auf der Länderebene zu beurteilen. Die Ergebnisse eröffnen darüber hinaus neue theoretische und empirische Perspektiven für die verwandte Forschung zur Unterstützung und Zufriedenheit mit der Demokratie sowie zur Demokratisierung.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Recent developments indicate that democracy is facing challenges across the world. While some established democracies are backsliding due to the erosion of liberal principles such as civil liberties and the rule of law (Abramowitz and Repucci 2018; Mechkova et al 2017; Repucci 2020; Schenkkan and Repucci 2019), governmental attacks on the media and freedom of expression are accelerating and deepening the third wave of autocratization (Lührmann and Lindberg 2019; Lührmann et al 2019; Maerz et al 2020). These developments are accompanied by the global rise of (right-wing) populist parties and authoritarian leaders that embody alternative concepts of democracy and oppose fundamental liberal principles and democratic procedures (Galston 2018; Heinisch and Wegscheider 2020; Huber and Schimpf 2017; Mudde 2007; Norris and Inglehart 2019; Pappas 2016; Plattner 2019).

Studies on the global support for democracy highlight the uncertain future of democractic governance and raise the question whether democracy is (still) “the only game in town” (Linz and Stepan 1996, 15): Recent research suggests that citizens’ support for democracy has declined, while openness to illiberal and authoritarian alternatives has increased (Foa and Mounk 2016, 25,26,a,b; Global Barometer Surveys 2018; Howe 2017). These findings are particularly worrying in light of evidence that indicates that public support for democracy helps democracy to survive (Claassen 2020), while a lack of democratic support and openness to illiberal and authoritarian alternatives is associated with democratic backsliding (Foa and Mounk 2019).

Alongside citizens’ belief in the legitimacy of democracy, however, public support for the political regime is crucial to the survival of (democratic) political systems (Easton 1965, 1975; Norris 1999, 2011; Pickel 2016). Yet, several long-term trends and observations indicate high levels of distrust towards political institutions and dissatisfaction with their democratic performance (Armingeon and Guthmann 2014; Crozier et al 1975; Dalton 2004; Global Barometer Surveys 2018; Klingemann 1999; Norris 2011; Pharr and Putnam 2000; Wike and Fetterolf 2018). While some scholars argue that this lack of regime support is an expression of a growing assertive and critical citizenry with higher expectations and demands on political institutions (Dalton and Welzel 2014; Norris 1999, 2011; Welzel 2013), others argue that it is rooted in a lack of belief in fundamental principles of democracy and a widespread openness to illiberal and authoritarian alternatives among younger cohorts (Foa and Mounk 2016, 25,26,a,b, 2019).

At the heart of this discussion lies the question which democratic norms and values citizens have internalized through their political socialization, thus constituting their democratic knowledge, and how this understanding of democracy affects their evaluation of their country’s political regime. This question is particularly important given that substantial gaps between citizens’ democratic knowledge and perceived democratic practice may foster potential pro- or anti-democratic mobilizations (Stark 2019; Welzel and Klingemann 2008). However, besides a few studies focusing primarily on established democracies in Europe (Ferrín 2016; Heyne 2019b; Markowski 2016; Pickel 2016, 2017; Torcal and Trechsel 2016; Weßels 2016), we know fairly little about the relationship between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their evaluation of democratic performance from a global comparative perspective.

In this article, we argue that citizens’ democratic knowledge constitutes the individual yardstick for assessing democracy in practice. In other words, we expect that the extent to which citizens are cognitively able to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian characteristics entails different evaluations of political institutions. This argument is based on the assumption that citizens’ support for political objects is rooted in a certain understanding of democracy which is the result of the political socialization process (Pickel 2016). In this case, the understanding of democracy is operationalized through citizens’ knowledge of the academic distinction between democratic and authoritarian regime principles. Accordingly, we expect that the extent of citizens’ democratic knowledge affects whether and to what extent they are satisfied with the level of democracy provided by the country.

However, we further argue that citizens tend to evaluate democracy in their country more positively if political institutions meet their knowledge about democracy. We therefore anticipate that the effect of citizens’ democratic knowledge on their evaluation of democratic performance is moderated by the institutional level of democracy. While we expect the effect of democratic knowledge on citizens’ assessment of democratic performance to be more positive the higher a country’s level of democracy, we assume the effect to be more negative the lower a country’s level of democracy. Accordingly, our research question is how citizens’ democratic knowledge and the institutional level of democracy affect their evaluation of democratic performance?

To answer this research question, the remainder of this article is structured as follows: First, we give a brief overview of the importance of citizens’ assessment of democracy within the concept of political support and explain why it is essential to consider citizens’ democratic knowledge and the institutional level of democracy. After presenting our hypotheses, we operationalize the theoretical concepts using data from the sixth and seventh wave of the World Values Survey and the third pre-release of the European Values Study 2017. Using data from 114 representative samples of 80 countries with a total of 128,127 respondents, we test our hypotheses by applying multilevel regression modeling. In the final section, we conclude with important theoretical and empirical considerations for further research.

2 Theoretical Framework

In this article, we argue that citizens’ evaluation of democratic performance is significantly shaped by their democratic knowledge and that this relationship is moderated by their country’s level of democracy. To highlight the relevance of this assumption for political culture research, we begin by locating citizens’ assessment of democracy within the concept of political support. In a second step, we explain the need to consider the knowledge of democracy that citizens have acquired during their political socialization, since this specific understanding of democracy is considered the foundation of support for the political system (Pickel 2016). In a final step, we outline how the relationship between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their evaluation of democracy is influenced by their country’s level of democracy. We assume that citizens who have a distinct knowledge of democracy but live under different political regimes hold different perceptions of how democratic their country is. The following section provides a framework for this study and outlines our assumptions.

2.1 Political Support and Citizens’ Assessment of Democratic Performance

The significance of people’s political attitudes and values for the stability of political systems has been theorized in detail since the civic culture study by Almond and Verba (1963). Accordingly, the persistence of a political system is largely determined by citizens’ cognitive, affective and evaluative orientations towards political objects. Easton defines these orientations as political support, “an attitude by which a person orients himself to an object either favorably or unfavorably, positively or negatively” (Easton 1975, 436). However, a political object only receives support if it corresponds to the value orientations and attitudes as well as the expectations and knowledge of the people (Pickel 2016). While citizens may have positive or negative views towards political authorities and the political community, public support for the political regime and belief in the legitimacy of democracy are crucial for the survival of (democratic) political systems (Claassen 2020).

Regime support is frequently measured using citizens’ satisfaction with or evaluation of the democratic performance, as these indicators are available in most surveys and therefore well suited for comparative studies (Dalton 2004; Klingemann 1999; Martini and Quaranta 2020; Norris 1999, 2011; Torcal and Montero 2006). Several studies have shown that while these indicators tap into multiple dimensions of political support and also cover the evaluation of non-democratic aspects (e.g. economic wealth), they still provide an acceptable measure for citizens’ assessment of democracy (Canache et al 2001; Ferrín 2016; Linde and Ekman 2003; Quaranta 2018). Thus, these indicators provide an evaluation of the extent to which democratic institutions and their functioning in practice meet the preferences of citizens. These preferences for democracy are shaped by the knowledge about fundamental principles, institutions and procedures associated with the concept of democracy that people acquire in the course of their political socialization. Accordingly, democratic knowledge refers to the cognitive dimension of attitudes towards democracy, which is synonymous with the understanding of democracy (Shin and Kim 2018). Citizens’ assessment of democracy should therefore be considered in the light of their knowledge about democratic procedures.

Despite this explicit connection, only few studies consider the gap between attitudes towards democracy and democratic practice when explaining citizens’ satisfaction with or evaluation of democratic performance (Ferrín 2016; Heyne 2019b; Markowski 2016; Torcal and Trechsel 2016; Weßels 2016). Overall, the results show that citizens’ attitudes towards democracy significantly influence their evaluation of democracy in their country. However, these studies mainly refer to established democracies in Europe, which significantly reduces the variance in the level of democracy at the country level. As a result, we still know fairly little about the relationship between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their assessment of democratic performance within different institutional settings ranging from highly democratic to authoritarian regimes.

2.2 The Concept of Democratic Knowledge

As Galston argues, democracies “require democratic citizens, whose specific knowledge, competences, and character would not be as well suited to nondemocratic politics” (Galston 2001, 217). Yet alongside good education, literacy and access to free media, the type of political regime and its historical development of democracy in particular give rise to distinctive democratic knowledge and competences among citizens (Cho 2014, 2015; Kirsch and Welzel 2019; Kruse et al 2019; Norris 2011; Welzel 2013; Welzel and Alvarez 2014). Accordingly, what people know about democracy is closely linked to the process of political socialization, because “political knowledge, behavioral norms, and cultural values are acquired from formative experiences occurring during earliest childhood through adolescence and beyond” (Norris 2011, 143–144). Hence, the yardstick by which citizens evaluate democratic institutions does not only depend on the acquired democratic knowledge, but also on the democratic or authoritarian context in which this knowledge was conveyed.

While ordinary citizens may lack knowledge about what constitutes a democracy, political scientists have established distinct criteria that characterize democratic regimes. The normative core of every procedural definition of democracy is determined by the integrity of the electoral process (Diamond and Morlino 2005; Ferrín and Kriesi 2016a; Held 2006; Norris 2014). A representative democracy can only generate legitimacy among its citizens if the electoral competition is protected by additional measures aimed at accountability and responsiveness (Bühlmann and Kriesi 2013). Proceeding from this electoral dimension, the concept of democracy can be expanded by a liberal, social or direct dimension if certain elements such as the rule of law and civil liberties, protection against poverty or direct popular participation are included (Coppedge et al 2011; Ferrín and Kriesi 2016a; Hernández 2016; Kriesi et al 2016).

While some scholars argue that these concepts of democracy are too complex and controversial to be clearly identified by ordinary citizens (Schaffer 1998), others add the methodological criticism that attitudes towards democracy are in general difficult to measure with surveys (Converse 2006). Furthermore, the mere focus on democratic principles is criticized since citizens only really know about democracy if they are cognitively able to identify authoritarian principles as undemocratic (Schedler and Sarsfield 2007; Schmitter and Karl 1991). In contrast to Ferrín and Kriesi (2016b) or Heyne (2019b), who measure support for the electoral, liberal, social and direct dimensions of democracy, we thus focus on citizens’ democratic knowledge as their cognitive ability to distinguish democratic from authoritarian regime principles. This ties in with previous research, according to which citizens are knowledgeable about democracy only if they are also able to recognize and reject authoritarian regime characteristics (Cho 2014, 2015; Kirsch and Welzel 2019; Norris 2011; Welzel 2013; Welzel and Alvarez 2014). Furthermore, this simplification allows us to examine knowledge about democracy from a cross-cultural perspective that covers the entire spectrum from highly democratic countries to authoritarian regimes.

2.3 The Interaction of Citizens’ Democratic Knowledge and Institutional Level of Democracy

In addition to citizens’ knowledge about democracy, previous research emphasized to consider the influence of macro-level factors on the evaluation of democracy. Thus, recent studies show that the individual assessment of democracy largely depends on a country’s historical experience with democracy (Kruse et al 2019; Heyne 36,35,b,a; Norris 2019), the number of parties (Berggren et al 2004), the quality of government (Martini and Quaranta 2020) and the economic performance (Daoust and Nadeau 2020; Pennings 2017).

Despite these findings, only few studies have examined causes of citizens’ assessment of democracy outside established (Western) democracies and have included non-Western democracies and authoritarian regimes. In addition, the institutional level of democracy has rarely been considered as a moderating variable. Consequently, we consider the level of democracy across different democratic and authoritarian regimes, which enables us to examine to what extent a country’s level of democracy meets citizens’ democratic knowledge and whether this influences their evaluation of the democratic performance. This further allows us to assess the extent to which citizens’ evaluation of democracy results from a gap between democratic knowledge and democratic practice.

To sum up, we argue that the cognitive ability of citizens to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian characteristics constitutes their individual yardstick for the evaluation of democratic performance in their country. Yet, citizens should be more likely to support the political regime in their country, the more the level of democracy corresponds to their knowledge of democracy. This implies that the evaluation of democracy is also determined by the institutional framework, and that citizens with high knowledge of democracy should be most cognitively able to assess the level of democracy in line with country-level measures of democracy. Citizens with high levels of democratic knowledge should therefore evaluate democracy in their country higher in highly democratic countries, as these political regimes are most likely to meet their knowledge about democracy. In contrast, citizens with a high level of democratic knowledge should evaluate democracy lower the more authoritarian a country is, since this increases the gap between democratic knowledge and democratic practice. Accordingly, we expect the effect of democratic knowledge on citizens’ assessment of democratic performance to be more positive the higher a country’s level of democracy (H1), while we expect the effect to be more negative the lower a country’s level of democracy (H2).

3 Data and Methods

We test these hypotheses by combining survey data from the sixth and seventh wave of the World Values Survey (WVS) (Haerpfer et al 2020; Inglehart et al 2014) and the third pre-release of the European Values Study (EVS) 2017 (EVS 2020). The WVS and EVS use a common questionnaire and include representative samples from almost one hundred countries, making it the largest cross-national survey project on people‘s value orientations and attitudes. The most recent surveysFootnote 1 are particularly well suited as they contain questions both on citizens’ assessment of their country’s democratic performance and on their cognitive skills to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian characteristics. In addition, the combination of these surveys allows covering respondents from the whole range of highly democratic countries such as Sweden, New Zealand, Uruguay and Germany to authoritarian regimes like Nicaragua, Tajikistan, Libya and Rwanda. Given that some countries are included in both the sixth and the seventh wave of the WVS or the EVS 2017, we use the year in which the survey was conducted as a suffix (country-year) for unique identification. After deleting observations with missing values for the variables of interest described below, the final data include 114 representative samples from 80 countries with a total of 128,127 respondents. Table 3 in the Appendix lists all country samples included in the analysis.

Table 4 in the Appendix provides further information on all variables used in our analyses, such as question wording and coding. We normalize all variables within a range from 0 to 1.0 to allow for comparison of coefficients and simplify the interpretation of our analyses. The dependent variable is citizens’ assessment of their country’s democratic performance and thus their individual perception of the functioning of democratic institutions in practice. We measure this evaluation by the extent to which respondents indicate how democratically their country is governed, on a ten-point scale ranging from not at all democratic (0) to completely democratic (1.0).

The main explanatory variable is citizens’ democratic knowledge and thus their cognitive abilities to distinguish democratic from authoritarian regime principles. As outlined in the theoretical section, we expect that the extent of democratic knowledge provides the individual yardstick for the evaluation of the functioning of democratic institutions in practice. We measure citizens’ democratic knowledge using the six indicators summarized in Table 1. Respondents are asked how essential they consider each characteristic for democracyFootnote 2 on a ten-point scale from not an essential characteristic of democracy (0) to an essential characteristic of democracy (1.0)Footnote 3. Drawing on previous research (Kirsch and Welzel 2019; Norris 2011; Welzel 2013; Welzel and Alvarez 2014), we assign three characteristics each to either democratic or authoritarian regime principles: While we consider free elections, gender equality and the protection of people through civil rights to be essential democratic principles, we assign preferences for a military coup, a theocratic regime and an obedient society to authoritarian regime principles.

The results of the principal component analysis, as presented in Table 1, confirm the theoretical dimensions of democratic and authoritarian regime principles. We measure citizens’ democratic knowledge using their cognitive ability to distinguish between these democratic and authoritarian characteristics. For this purpose, we first calculate an additive index, measuring knowledge of democratic regime principles by adding the values of the three indicators for each respondent and normalizing the resulting index between 0 and 1.0. Here the value of 1.0 indicates the respondent’s ability to identify all three democratic regime principles as essential characteristics for democracy. In contrast, we add the inverted values of the three authoritarian characteristics and normalize the index between 0 and 1.0, with 1.0 representing a comprehensive knowledge of authoritarian regime principles as non-essential characteristics of democracy. Following the logic of non-compensatory index construction (Wuttke et al 2020)Footnote 4, we multiply both indices. This results in an index of citizens’ democratic knowledge between 0 and 1.0, where 1.0 indicates a comprehensive knowledge about democratic principles as essential characteristics for democracy and of authoritarian regime principles as non-essential characteristics of democracy. When interpreting this index, it should be noted that this index only reflects citizens’ cognitive ability to distinguish between democratic and autocratic characteristics. Evaluating authoritarian characteristics as essential for democracy does not necessarily mean that citizens support them, but rather that they lack democratic knowledgeFootnote 5.

In addition, we include a number of control variables that we consider important for the individual assessment of democratic performance. We use general life satisfaction and household income as proxies for the evaluation of the perceived effectiveness and general performance of a country. We measure general life satisfaction on a ten-point scale ranging from completely dissatisfied (0) to completely satisfied (1.0) and household income on a ten-point scale from lowest income group (0) to highest income group (1.0). For political ideology, we use the self-positioning on a ten-point scale from left (0) to right (1.0). We measure cognitive skills using political interest on a four-point scale from not at all interested (0) to very interested (1.0) and the highest educational level on a nine-point scale from no formal education (0) to university-level education with degree (1.0). We also control for the gender and age of respondents.

To measure a country’s level of democracy, we rely on data from the tenth version of the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-Dem) (Coppedge et al 2020; Pemstein et al 2020). V‑Dem takes into account the multidimensionality of the concept of democracy (Coppedge et al 2011) and provides indices based on multiple indicators and sub-components coded by country experts, thereby reducing the measurement error (Teorell et al 2019). We use the liberal democracy index (\(v2x\_\textit{libdem}\)), which measures a country’s level of democracy on a scale from low (0) to high levels of liberal democracy (1.0). This index takes into account the extent to which electoral principles such as freedom of association and expression, universal suffrage and free and fair elections are implemented (\(v2x\_\textit{polyarchy}\)), as well as compliance with liberal principles such as the rule of law and protection of individual and minority rights (\(v2x\_\textit{liberal}\)). We use the value of the liberal democracy index for the year in which the survey was conducted in the respective country. For those countries surveyed in 2020, we use the value of the liberal democracy index from 2019. As an additional robustness test and to control for short-term fluctuations, we measure the level of democracy using the arithmetic mean of the values for the year in which the survey was conducted and the four previous yearsFootnote 6.

We test our hypotheses by applying multilevel regression modeling. This method has the advantage that it takes into account the hierarchical structure of our data from respondents nested in countries (Hox 2010; Steenbergen and Jones 2002). Applying multilevel modeling allows us to analyze the expected different slopes in the relationship between democratic knowledge and citizens’ assessment of democratic performance. Most importantly, it enables us to test our hypotheses about the cross-level interaction between democratic knowledge and the level of democracy. We provide further information such as descriptive statistics (Table 5) and distributions of the variables measuring citizens’ assessment of democratic performance (Fig. 3), democratic knowledge (Fig. 4) and level of democracy (Fig. 5) in the Appendix.

4 Empirical Analysis

Using the described data, measurements and methods, we analyze in this section how democratic knowledge and the level of democracy interact in influencing citizens’ assessment of democratic knowledge. We begin by analyzing the shape of the relationship between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their evaluation of democracy. As outlined in the theoretical section, we expect this relationship to be either positive or negative, depending on a country’s level of democracy. Specifically, we hypothesized that the higher a country’s level of democracy, the more positive is the effect of citizens’ democratic knowledge on their assessment of democratic performance (H1). In contrast, we expect the effect to be more negative the lower the level of democracy of a country (H2).

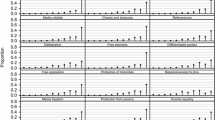

Figure 1 illustrates the bivariate relationship for a sample of forty countries. The eight countries in each of the five rows represent a group with a comparable level of democracy: While the first row comprises the eight countries with the lowest level of democracy in our data, the last row covers the most democratic countries. The row in the center shows the bivariate relationship for the eight countries grouped around the average level of democracy. The second and fourth rows show the eight countries grouped by minus and plus one standard deviation from the mean level of democracy.

The scatterplots show remarkable differences across countries in the relationship between citizens’ knowledge of democracy and their assessment of democratic performance. For the countries in the first two rows with comparatively low levels of democracy, we observe mainly negative correlations. Accordingly, citizens with high democratic knowledge living in more authoritarian regimes seem to evaluate the democratic performance more negatively. In the sample of countries with a medium level of democracy, we also find rather negative correlations, although less clear and with a flattening effect. In contrast, we find mainly positive relationships for the countries in the last two rows with comparatively high levels of democracy. Hence, citizens with a high level of democratic knowledge in highly democratic countries seem to evaluate democratic performance more positively. Alongside initial descriptive evidence for our assumptions, the differences in intercepts and slopes illustrate the importance of multilevel modeling for testing our hypotheses.

We follow a stepwise approach in building nested models to ensure that each more complex model adds substantial explanatory power. Table 2 summarizes the results of our analysis. Model 1 represents the null model and only includes the varying intercepts at the country level. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) is 0.195, which means that about 19% of the variance at the individual level can be explained by country level differences. Model 2 includes all independent variables, while we add a random slope for democratic knowledge in Model 3, which allows us to take into account the differences in the relationship between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their assessment of democratic performance. In the final Model 4, we also add the cross-level interaction between citizens’ democratic knowledge and a country’s level of democracy. All the following substantive interpretations refer to our final Model 4.

The first thing to note is that we do not find a general effect of democratic knowledge on citizens’ evaluation of democracy. When we include the random effect for democratic knowledge in Model 3 and thus control for the different slopes of the effect between countries, the effect turns out to be not significant. In other words, we find no evidence that there is an effect of democratic knowledge on citizens’ assessment of democratic performance that is independent of a country’s level of democracy. However, we find a significant positive effect of the level of democracy. The higher the level of democracy of a country, the higher citizens evaluate its democratic performance. In terms of effect sizes, a citizen living in the most democratic country rates the democratic performance on average about 0.16 points higher than someone living in the most authoritarian country included in our data. Thus, citizens across the globe seem to be quite well aware of how democratic their country really is. Indeed, they seem to be able to judge the level of democracy in their country based on the freedoms and opportunities it provides, although there are significant differences in accuracy between citizens (Kruse et al 2019).

Our main argument is that these differences can be explained by citizens’ democratic knowledge, which provides the individual yardstick for evaluating the functioning of democratic institutions in practice. According to this, citizens assess the democratic performance of their country based on their knowledge of democracy in relation to the perceived level of democracy. Consequently, citizens with a high democratic knowledge should be more likely to hold positive views about democracy in their country within a highly democratic context, whereas they should have a more negative view of the political institutions within an authoritarian context.

The significant positive coefficient of the cross-level interaction between citizens’ democratic knowledge and their country’s level of democracy confirms our hypotheses. Accordingly, a person with high democratic knowledge in the most democratic country in our data evaluates the democratic performance on average about 0.3 points higher than a person with high democratic knowledge in the most authoritarian country. We visualized the effects of the cross-level interaction in Fig. 2 to facilitate the interpretation. As the left-hand figure (2a) shows, the estimated effect of democratic knowledge becomes more positive the higher a country’s level of democracy. Accordingly, citizens who are knowledgeable about democracy rate the democratic performance in their country more positively the higher the actual level of democracy (H1). While we find no significant effect of democratic knowledge around the mean level of democracy, the estimated coefficient of democratic knowledge becomes more negative the lower a country’s level of democracy. Correspondingly, citizens with the cognitive abilities to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian regime principles evaluate the democratic performance of their country lower the more authoritarian it is (H2).

Cross-Level Interaction between Level of Democracy and Democratic Knowledge. Notes: Left-hand figure (a) shows the estimated coefficients (marginal effects) of democratic knowledge on assessment of democratic performance dependent on different levels of democracy. Right-hand figure (b) shows the predicted values of assessment of democratic performance at different levels of democratic knowledge (x-axis) and levels of democracy (+1 standard deviation of the mean level of democracy; mean level of democracy; -1 standard deviation of the mean level of democracy). Coefficients are from Model 4 in Table 2 with 95% confidence intervals

These results are further verified by the predicted values of the assessment of democratic performance shown in the right-hand figure (2b) of Fig. 2. For citizens living in countries with an above-average level of democracy, the assessment of democratic performance turns out to be higher with increasing democratic knowledge (H1). In contrast, citizens living in countries with a below-average level of democracy rate democracy in their country lower with increasing democratic knowledge (H2). As stated before, we find no significant effect of democratic knowledge for countries with an average level of democracy. Depending on the specific process of democratization or autocratization that these regimes are facing, it seems likely to find both positive and negative effects in this group of countries, resulting on average in a null effect.

Another important finding is that the level of democracy appears to make no difference at all for citizens who are less aware about democracy. Thus, we find that citizens with a lack of democratic knowledge evaluate democracy in their country regardless of the context in which they live. This raises an important question for further research, namely the criteria by which citizens who are less aware of democracy assess the democratic performance of their country. Furthermore, this study also shows that citizens who are knowledgeable about democracy are most cognitively able to assess the level of democracy in line with country-level measures of democracy (Pickel et al 2016). These results open up new theoretical and empirical perspectives for related research on support of and satisfaction with democracy as well as research on democratization.

5 Conclusion

We analyzed in this study how democratic knowledge and the level of democracy interact in influencing citizens’ assessment of democratic performance. We started from the point that both citizens’ belief in the legitimacy of democracy and their support for the political regime are crucial to the survival of a (democratic) political system. Our main argument was that the cognitive ability of citizens to distinguish between democratic and authoritarian characteristics constitutes the individual yardstick for the assessment of democracy in practice and that this relationship is moderated by the institutional level of democracy.

Our results show that citizens’ evaluation of democracy varies significantly depending on their democratic knowledge and their country’s level of democracy. We find that the more authoritarian the regime, the more negative the evaluation of democratic performance by people who are more knowledgeable about democracy. In contrast, we find that the more democratic the regime, the more positive is the assessment of democracy by people with high democratic knowledge. These results show that citizens who are knowledgeable about democracy are most cognitively able to assess the level of democracy in line with country-level measures of democracy.

The results are less clear in regimes located between highly democratic and authoritarian regimes. For these countries, we find on average no significant effect of citizens’ democratic knowledge on their evaluation of democracy. This is quite reasonable from an empirical perspective, given that this group includes both positive and negative effects, which on average results in a null effect. From a theoretical perspective, it seems likely that unstable or changing political conditions also lead to different effects of democratic knowledge on the evaluation of democracy among the population. Further research should address not only the question of what kind of understanding of democracy prevails among citizens in these regimes, but also the resulting political consequences.

Hence, our results provide some important theoretical and empirical implications for further research. First, they prepare the ground for further research on the legitimacy and stability of authoritarian regimes. Follow-up studies could examine the mechanisms between democratic knowledge and regime support within authoritarian regimes in more detail (e.g. Kirsch and Welzel 2019). Second, further studies could look more closely at cohort effects within countries. Older cohorts that were socialized under a more authoritarian regime can be expected to have different evaluations of political institutions than younger generations that grew up in a more democratic context. Third, the use of time series data can be used to study changes in the effect of democratic knowledge on regime support due to changes in the level of democracy. If the effect of democratic knowledge on regime support changes as a result of the democratization or autocratization of a country, this has far-reaching consequences for the mobilization of pro- and anti-democratic movements (Stark et al 2017; Stark 2019; Welzel and Klingemann 2008). This brings us to a fourth possible application for party competition and electoral behavior: If political parties can mobilize voters based on a certain conception of democracy, and if this is a sufficient reason for people to support these parties, this represents both a potential and a threat to democratization.

Following the topic of this special section on measuring meanings of democracy, further reflection is needed on how to measure citizens’ attitudes towards democracy from a global comparative perspective. While we focus on the cognitive dimension of citizens’ attitudes towards democracy, and thus a certain understanding of democracy, its theoretical and empirical relationship to specific preferences for democratic procedures is still under-researched. While this requires a systematic review of the theoretical concepts and terms, taking into account available empirical items and scales (e.g. Shin and Kim 2018), it allows further advances and important insights for this field of comparative politics.

Notes

While the sixth wave of the WVS was conducted between 2010 and 2014, the seventh wave of the WVS and the third pre-release of the EVS 2017 cover the years 2017 to 2020.

The exact wording of the question is as follows: Many things are desirable, but not all of them are essential characteristics of democracy. Please tell me for each of the following things how essential you think it is as a characteristic of democracy.

In the seventh wave of the WVS and the EVS 2017, the category it is against democracy (0) was additionally coded. In order to compare the questions across countries, we recoded all values of 0 into 1 (not an essential characteristic of democracy).

We prefer a multiplicative index because we argue that low knowledge of authoritarian regime principles as non-essential characteristics of democracy cannot be compensated by high knowledge about democratic ones. As a robustness test, we perform the analysis using an additive combination of indicators. As shown in Tables 6 and 8, results remain substantially the same.

In contrast to Kirsch and Welzel (2019), we refrain from using the term liberal (notions of) democracy because we believe that the employed items are too thin to measure a concept as complex as liberal democracy.

References

Abramowitz, M.J., and S. Repucci. 2018. Democracy beleaguered. Journal of Democracy 29(2):128–142. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0032.

Almond, G.A., and S. Verba. 1963. The civic culture: political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Armingeon, K., and K. Guthmann. 2014. Democracy in crisis? the declining support for national democracy in european countries, 2007-2011. European Journal of Political Research 53(3):423–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12046.

Berggren, H.M., G.A. Fugate, R.R. Preuhs, and D.R. Still. 2004. Satisfied? institutional determinants of citizen evaluations of democracy. Politics & Policy 32(1):72–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2004.tb00176.x.

Bühlmann, M., and H. Kriesi. 2013. Models for democracy. In Democracy in the age of globalization and mediatization, ed. H. Kriesi, S. Lavenex, F. Esser, J. Matthes, M. Bühlmann, and D. Bochsler, 44–68. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137299871_3.

Canache, D., J.J. Mondak, and M.A. Seligson. 2001. Meaning and measurement in cross-national research on satisfaction with democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly 65(4):506–528. https://doi.org/10.1086/323576.

Cho, Y. 2014. To know democracy is to love it. a cross-national analysis of democratic understanding and political support for democracy. Political Research Quarterly 67(3):478–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912914532721.

Cho, Y. 2015. How well are global citizenries informed about democracy? ascertaining the breadth and distribution of their democratic enlightenment and its sources. Political Studies 63(1):240–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12088.

Claassen, C. 2020. Does public support help democracy survive? American Journal of Political Science 64(1):118–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12452.

Converse, P.E. 2006. The nature of belief systems in mass publics (1964). Critical Review 18(1-3):1–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913810608443650.

Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, D. Altman, M. Bernhard, S. Fish, A. Hicken, M. Kroenig, S.I. Lindberg, K. McMann, P. Paxton, H.A. Semetko, S.E. Skaaning, J. Staton, and J. Teorell. 2011. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: a new approach. Perspectives on Politics 9(2):247–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592711000880.

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Knutsen CH, Lindberg SI, Teorell J, Altman D, Bernhard M, Fish MS, Glynn A, Hicken A, Lührmann A, Marquardt KL, McMann K, Paxton P, Pemstein D, Seim B, Sigman R, Skanning SE, Staton J, Wilson S, Cornell A, Gastaldi L, Gjerløw H, Ilchenko N, Krusell J, Maxwell L, Mechkova V, Medzihorsky J, Pernes J, von Römer J, Stepanova N, Sundström A, Tzelgov E, Wang Yt, Wig T, Ziblatt D (2020) V‑dem [country–year/country–date] dataset v10. varieties of democracy (v-dem) project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20

Crozier, M., S.P. Huntington, and J. Watanuki. 1975. The crisis of democracy: report on the governability of democracies to the Trilateral Commission. New York: New York University Press.

Dalton, R.J. 2004. Democratic challenges, democratic choices: the erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199268436.001.0001.

Dalton, R.J., and C. Welzel (eds.). 2014. The civic culture transformed: from allegiant to assertive citizens. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139600002.

Daoust, J.F., and R. Nadeau. 2020. Context matters: Economics, politics and satisfaction with democracy. Electoral Studies https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102133.

Diamond, L.J., and L. Morlino (eds.). 2005. Assessing the quality of democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press.

Easton, D. 1965. A systems analysis of political life. New York: Wiley.

Easton, D. 1975. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5(4):435–457. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008309.

EVS. 2020. European values study 2017: integrated dataset (evs 2017). za7500 data file version 3.0.0. Cologne: gesis data archive. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13511.

Ferrín, M. 2016. An empirical assessment of satisfaction with democracy. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 283–306. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0013.

Ferrín, M., and H. Kriesi (eds.). 2016a. How Europeans view and evaluate democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.001.0001.

Ferrín, M., and H. Kriesi. 2016b. Introduction: democracy—the European verdict. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 1–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0001.

Foa, R.S., and Y. Mounk. 2016. The democratic disconnect. Journal of Democracy 27(3):5–17. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0049.

Foa, R.S., and Y. Mounk. 2017a. The end of the consolidation paradigm: a response to our critics. Journal of Democracy (Online Exchange). https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exchange-democratic-deconsolidation/. Accessed 10.02.2020.

Foa, R.S., and Y. Mounk. 2017b. The signs of deconsolidation. Journal of Democracy 28(1):5–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0000.

Foa, R.S., and Y. Mounk. 2019. Democratic deconsolidation in developed democracies, 1995-2018. https://ces.fas.harvard.edu/uploads/art/Working-Paper-PDF-Democratic-Deconsolidation-in-Developed-Democracies-1995-2018.pdf. Accessed 10.02.2020.

Galston, W.A. 2001. Political knowledge, political engagement, and civic education. Annual Review of Political Science 4(1):217–234. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.217.

Galston, W.A. 2018. The populist challenge to liberal democracy. Journal of Democracy 29(2):5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0020.

Global Barometer Surveys. 2018. Exploring support for democracy across the globe. report on key findings. https://www.globalbarometer.net/FileServlet?method=DOWNLOAD&fileId=1541553519620.pdf. Accessed 10.02.2020.

Haerpfer, C., R. Inglehart, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, B. Puranen, et al. 2020. World values survey: Round seven - country-pooled datafile. madrid, spain & vienna, austria: Jd systems institute & wvsa secretariat. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvsdocumentationwv7.jsp.

Heinisch, R., and C. Wegscheider. 2020. Disentangling how populism and radical host ideologies shape citizens’ conceptions of democratic decision-making. Politics and Governance 8(3):32–44. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i3.2915.

Held, D. 2006. Models of democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hernández, E. 2016. Europeans’ views of democracy. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 43–63. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0003.

Heyne, L. 2019a. Democratic demand and supply: a spatial model approach to satisfaction with democracy. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 29(3):381–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2018.1544904.

Heyne, L. 2019b. The making of democratic citizens: How regime-specific socialization shapes europeans’ expectations of democracy. Swiss Political Science Review 25(1):40–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12338.

Howe, P. 2017. Eroding norms and democratic deconsolidation. Journal of Democracy 28(4):15–29. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0061.

Hox, J.J. 2010. Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. New York: Routledge.

Huber, R.A., and C. Schimpf. 2017. Populism and democracy: theoretical and empirical considerations. In Political populism, ed. R. Heinisch, C. Holtz-Bacha, and O. Mazzoleni, 329–344. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Inglehart, R., C. Haerpfer, A. Moreno, C. Welzel, K. Kizilova, J. Diez-Medrano, M. Lagos, P. Norris, E. Ponarin, B. Puranen, et al. 2014. World values survey: round six - country-pooled datafile. madrid: Jd systems institute. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/wvsdocumentationwv6.jsp.

Kirsch, H., and C. Welzel. 2019. Democracy misunderstood: authoritarian notions of democracy around the globe. Social Forces 98(1):59–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy114.

Klingemann, H.D. 1999. Mapping political support in the 1990s: a global analysis. In Critical citizens, ed. P. Norris, 31–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0198295685.003.0002.

Kriesi, H., W. Saris, and P. Moncagatta. 2016. The structure of Europeans’ views of democracy. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 64–89. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0004.

Kruse, S., M. Ravlik, and C. Welzel. 2019. Democracy confused: when people mistake the absence of democracy for its presence. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 50(3):315–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118821437.

Linde, J., and J. Ekman. 2003. Satisfaction with democracy: A note on a frequently used indicator in comparative politics. European Journal of Political Research 42(3):391–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00089.

Linz, J.J., and A.C. Stepan. 1996. Toward consolidated democracies. Journal of Democracy 7(2):14–33. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1996.0031.

Lührmann, A., and S.I. Lindberg. 2019. A third wave of autocratization is here: what is new about it? Democratization 26(7):1095–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

Lührmann, A., S. Grahn, R. Morgan, S. Pillai, and S.I. Lindberg. 2019. State of the world 2018: democracy facing global challenges. Democratization 26(6):895–915. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1613980.

Maerz, S.F., A. Lührmann, S. Hellmeier, S. Grahn, and S.I. Lindberg. 2020. State of the world 2019: autocratization surges – resistance grows. Democratization 27(6):909–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2020.1758670.

Markowski, R. 2016. Determinants of democratic legitimacy. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 257–282. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0012.

Martini, S., and M. Quaranta. 2020. Citizens and democracy in Europe: contexts, changes and political support. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mechkova, V., A. Lührmann, and S.I. Lindberg. 2017. How much democratic backsliding? Journal of Democracy 28(4):162–169. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0075.

Mudde, C. 2007. Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492037.

Norris, P. (ed.). 1999. Critical citizens: global support for democratic government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Norris, P. 2011. Democratic deficit: critical citizens revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511973383.

Norris, P. 2014. Why electoral integrity matters. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, P. 2019. Do perceptions of electoral malpractice undermine democratic satisfaction? The US in comparative perspective. International Political Science Review 40(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118806783.

Norris, P., and R. Inglehart. 2019. Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pappas, T.S. 2016. Distinguishing liberal democracy’s challengers. Journal of Democracy 27(4):22–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2016.0059.

Pemstein, D., K.L. Marquardt, E. Tzelgov, Yt Wang, J. Medzihorsky, J. Krusell, F. Miri, and J. von Römer. 2020. The v‑dem measurement model: latent variable analysis for cross-national and cross-temporal expert-coded data, 5th edn., University of Gothenburg: Varieties of Democracy Institute. v‑dem working paper no. 21.

Pennings, P. 2017. When and where did the great recession erode the support of democracy? Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 11(1):81–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-017-0337-x.

Pharr, S.J., and R.D. Putnam. 2000. Disaffected democracies: what’s troubling the trilateral countries? Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pickel, S. 2016. Konzepte und Verständnisse von Demokratie in Ost- und Westeuropa. In „Demokratie“ jenseits des Westens, ed. S. Schubert, A. Weiß, 318–342. Baden-Baden: Nomos. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845261904-319.

Pickel, S. 2017. Unequal democracies in Europe: modes of participation, understanding, and perception of democracy. In Inequality in America Publications of the Bavarian American Academy., ed. B. Hahn, K. Schmidt, 25–44. Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter.

Pickel, S., W. Breustedt, and T. Smolka. 2016. Measuring the quality of democracy: Why include the citizens’ perspective? International Political Science Review 37(5):645–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512116641179.

Plattner, M.F. 2019. Illiberal democracy and the struggle on the right. Journal of Democracy 30(1):5–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0000.

Quaranta, M. 2018. How citizens evaluate democracy: an assessment using the European social survey. European Political Science Review 10(2):191–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773917000054.

Repucci, S. 2020. The freedom house survey for 2019: the leaderless struggle for democracy. Journal of Democracy 31(2):137–151. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0027.

Schaffer, F.C. 1998. Democracy in translation: understanding politics in an unfamiliar culture. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press.

Schedler, A., and R. Sarsfield. 2007. Democrats with adjectives: linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support. European Journal of Political Research 46(5):637–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2007.00708.x.

Schenkkan, N., and S. Repucci. 2019. The freedom house survey for 2018: democracy in retreat. Journal of Democracy 30(2):100–114. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0028.

Schmitter, P.C., and T.L. Karl. 1991. What democracy is. . . and is not. Journal of Democracy 2(3):75–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1991.0033.

Shin, D.C., and H.J. Kim. 2018. How global citizenries think about democracy: an evaluation and synthesis of recent public opinion research. Japanese Journal of Political Science 19(2):222–249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1468109918000063.

Stark, T. 2019. Demokratische Bürgerbeteiligung außerhalb des Wahllokals: Umbrüche in der politischen Partizipation seit den 1970er-Jahren. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Stark, T., C. Wegscheider, E. Brähler, and O. Decker. 2017. Sind Rechtsextremisten sozial ausgegrenzt? Eine Analyse der sozialen Lage und Einstellungen zum Rechtsextremismus. Papers 2/2017. Berlin: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung.

Steenbergen, M.R., and B.S. Jones. 2002. Modeling multilevel data structures. American Journal of Political Science 46(1):218. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088424.

Teorell, J., M. Coppedge, S. Lindberg, and S.E. Skaaning. 2019. Measuring polyarchy across the globe, 1900–2017. Studies in Comparative International Development 54(1):71–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9268-z.

Torcal, M., and J.R. Montero. 2006. Political disaffection in contemporary democracies. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203086186.

Torcal, M., and A.H. Trechsel. 2016. Explaining citizens’ evaluations of democracy. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 206–232. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0010.

Welzel, C. 2013. Freedom rising: human empowerment and the quest for emancipation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Welzel, C., and A.M. Alvarez. 2014. Enlightening people: the spark of emancipative values. In The civic culture transformed, ed. R.J. Dalton, C. Welzel, 59–88. New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139600002.007.

Welzel, C., and H.D. Klingemann. 2008. Evidencing and explaining democratic congruence: the perspective of “substantive” democracy. World Values Research 1(3):57–90.

Weßels, B. 2016. Democratic legitimacy. In How Europeans view and evaluate democracy, ed. M. Ferrín, H. Kriesi, 235–256. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766902.003.0011.

Wike, R., and J. Fetterolf. 2018. Liberal democracy’s crisis of confidence. Journal of Democracy 29(4):136–150. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0069.

Wuttke, A., C. Schimpf, and H. Schoen. 2020. When the whole is greater than the sum of its parts: on the conceptualization and measurement of populist attitudes and other multidimensional constructs. American Political Science Review 114(2):356–374. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055419000807.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Susanne Pickel, Robert A. Huber, Zoe Lefkofridi, Jan Schilling, Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann, Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach, the editors of the journal and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We presented an earlier version of this paper at the authors’ conference on “Measuring Understanding of Democracy: Discussing Solutions for Methodological Fallacies” (Berlin/August 2018) and are grateful for the comments of all participants.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Appendix

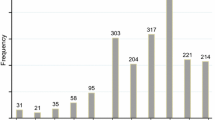

Random Effects of the Intercept. Notes: Coefficients are from Model 4 in Table 2 with 95% confidence intervals. If the point estimate or the 95% confidence intervals cross the horizontal line drawn at 0, the estimated coefficient is not significant. Blue points indicate a positive and red points a negative effect

Random Effects of Democratic Knowledge. Notes: Coefficients are from Model 4 in Table 2 with 95% confidence intervals. If the point estimate or the 95% confidence intervals cross the horizontal line drawn at 0, the estimated coefficient is not significant. Blue points indicate a positive and red points a negative effect

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wegscheider, C., Stark, T. What drives citizens’ evaluation of democratic performance? The interaction of citizens’ democratic knowledge and institutional level of democracy. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 14, 345–374 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-020-00467-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-020-00467-0