Abstract

Background

Cross-sectional studies suggest many people are unaware that cancer risk increases with age, but this misbelief has rarely been studied prospectively, nor are its moderators known.

Purpose

To assess whether people recognize that cancer risk increases with age and whether beliefs differ according to gender, education, smoking status, and family history of cancer.

Methods

First, items from the cross-sectional Health Information National Trends Survey (n = 2069) were analyzed to examine the association of age and perceived cancer risk. Second, the prospective National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (n = 3896) was used to assess whether perceived cancer risk changes over a decade. Third, beliefs about the age at which cancer occurs were analyzed using the US Awareness and Beliefs about Cancer survey (n = 1080). As a comparator, perceived risk of heart disease was also examined.

Results

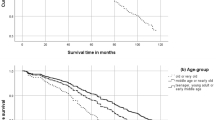

Cross-sectionally, older age was associated with lower perceived cancer risk but higher perceived heart disease risk. Prospectively, perceived cancer risk remained stable, whereas perceived heart attack risk increased. Seventy percent of participants reported a belief that cancer is equally likely to affect people of any age. Across three surveys, women and former smokers/smokers who recently quit tended to misunderstand the relationship between age and cancer risk and also expressed relatively higher perceived cancer risk overall.

Conclusions

Data from three national surveys indicated that people are unaware that age is a risk factor for cancer. Moreover, those who were least aware perceived the highest risk of cancer regardless of age.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Howlader N, Krapcho M, Garshell J, et al. Bethesda, MD, http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, 2015.

National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2014: With special feature on adults aged 55–64. Hyattsville. 2015.

Katapodi MC, Lee KA, Facione NC, Dodd MJ. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: A meta-analytic review. Prev Med. 2004, 38:388–402.

Rubinstein WS, O’Neill S M, Rothrock N, et al. Components of family history associated with women’s disease perceptions for cancer: A report from the family healthware impact trial. Genet Med. 2011, 13:52–62.

Peipins LA, McCarty F, Hawkins NA, et al. Cognitive and affective influences on perceived risk of ovarian cancer. Psychooncology. 2015, 24:279–286.

Gerend MA, Aiken LS, West SG, Erchull MJ. Beyond medical risk: Investigating the psychological factors underlying women’s perceptions of susceptibility to breast cancer, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Health Psychol. 2004, 23:247–258.

Vernon SW, Vogel VG, Halabi S, Bondy ML. Factors associated with perceived risk of breast cancer among women attending a screening program. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1993, 28:137–144.

Hamilton JG, Lobel M. Passing years, changing fears? Conceptualizing and measuring risk perceptions for chronic disease in younger and middle-aged women. J Behav Med. 2012, 35:124–138.

Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems: Conclusions from a community-wide sample. J Behav Med. 1987, 10:481–500.

Hay J, Coups E, Ford J. Predictors of perceived risk for colon cancer in a national probability sample in the United States. J Health Commun. 2006, 11 Suppl 1:71–92.

Buster KJ, You Z, Fouad M, Elmets C. Skin cancer risk perceptions: A comparison across ethnicity, age, education, gender, and income. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012, 66:771–779.

Honda K, Neugut AI. Associations between perceived cancer risk and established risk factors in a national community sample. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004, 28:1–7.

Breslow RA, Sorkin JD, Frey CM, Kessler LG. Americans’ knowledge of cancer risk and survival. Prev Med. 1997, 26:170–177.

Lucas-Wright A, Bazargan M, Jones L, et al. Correlates of perceived risk of developing cancer among African-Americans in South Los Angeles. J Community Health. 2014, 39:173–180.

McQueen A, Swank PR, Bastian LA, Vernon SW. Predictors of perceived susceptibility of breast cancer and changes over time: A mixed modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2008, 27:68–77.

DiLorenzo TA, Schnur J, Montgomery GH, et al. A model of disease-specific worry in heritable disease: The influence of family history, perceived risk and worry about other illnesses. J Behav Med. 2006, 29:37–49.

Erblich J, Bovbjerg DH, Norman C, Valdimarsdottir HB, Montgomery GH. It won’t happen to me: Lower perception of heart disease risk among women with family histories of breast cancer. Prev Med. 2000, 31:714–721.

Hamilton JG, Lobel M. Psychosocial factors associated with risk perceptions for chronic diseases in younger and middle-aged women. Women Health. 2015, 55:921–942.

Weinstein ND. Unrealistic optimism about susceptibility to health problems. J Behav Med. 1982, 5:441–460.

Stock ML, Gibbons FX, Beekman JB, Gerrard M. It only takes once: The absent-exempt heuristic and reactions to comparison-based sexual risk information. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015, 109:35–52.

Heiniger L, Butow PN, Charles M, Price MA. Intuition versus cognition: A qualitative exploration of how women understand and manage their increased breast cancer risk. J Behav Med. 2015, 38:727–739.

Orom H, O’Quin KE, Reilly S, Kiviniemi MT. Perceived cancer risk and risk attributions among African-American residents of a low-income, predominantly African-American neighborhood. Ethn Health. 2015, 20:543–556.

Vernon SW, Myers RE, Tilley BC, Li S. Factors associated with perceived risk in automotive employees at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10:35–43.

Cameron LD. Illness risk representations and motivations to engage in protective behavior: The case of skin cancer risk. Psychol Health. 2008, 23:91–112.

Berkowitz Z, Hawkins NA, Peipins LA, White MC, Nadel MR. Beliefs, risk perceptions, and gaps in knowledge as barriers to colorectal cancer screening in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008, 56:307–314.

Grunfeld EA, Ramirez AJ, Hunter MS, Richards MA. Women’s knowledge and beliefs regarding breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002, 86:1373–1378.

Dolan NC, Lee AM, McDermott MM. Age-related differences in breast carcinoma knowledge, beliefs, and perceived risk among women visiting an academic general medicine practice. Cancer 1997, 80:413–420.

Meischke H, Sellers DE, Robbins ML, et al. Factors that influence personal perceptions of the risk of an acute myocardial infarction. Behav Med. 2000, 26:4–13.

Renner B, Knoll N, Schwarzer R. Age and body make a difference in optimistic health beliefs and nutrition behaviors. Int J Behav Med. 2000, 7:143–159.

McQueen A, Vernon SW, Meissner HI, Rakowski W. Risk perceptions and worry about cancer: does gender make a difference? J Health Commun. 2008, 13:56–79.

Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Hesse BW, et al. The Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS): development, design, and dissemination. J Health Commun. 2004, 9:443–460.

Rutten LF, Moser RP, Beckjord EB, Hesse BW, Croyle RT. Cancer communication: Health Information National Trends Survey. Washington, DC.: National Cancer Institute, 2007.

Aiken, LS, West, SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 1991.

Forbes LJ, Simon AE, Warburton F, et al. Differences in cancer awareness and beliefs between Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK (the international cancer benchmarking partnership): Do they contribute to differences in cancer survival? Br J Cancer. 2013, 108:292–300.

Simon AE, Forbes LJ, Boniface D, et al. An international measure of awareness and beliefs about cancer: Development and testing of the ABC. BMJ Open. 2012, 2:e001758.

Grenen EG, Ferrer RA, Klein WM, Han PK. General and specific cancer risk perceptions: How are they related? J Risk Res. 2015:1–12.

Downs JS, Bruine De Bruin, W, Fischhoff, B, Hesse, BW, Maibach E. How people think about cancer: A mental models approach. In D. O’Hair (ed), Handbook of risk and crisis communication. Mahwah: Erlbaum, 2015.

Tomasetti C, Vogelstein B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science. 2015, 347:78–81.

Hay JL, Baser R, Weinstein ND, et al. Examining intuitive risk perceptions for cancer in diverse populations. Health Risk Soc. 2014, 16:227–242.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards

Jennifer M. Taber, William M.P. Klein, Jerry M. Suls, and Rebecca A. Ferrer declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

About this article

Cite this article

Taber, J.M., Klein, W.M.P., Suls, J.M. et al. Lay Awareness of the Relationship between Age and Cancer Risk. ann. behav. med. 51, 214–225 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9845-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-016-9845-1