Abstract

Background

Modification of expectancies (headache self-efficacy and headache locus of control) is thought to be central to the success of psychological treatments for migraine.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to examine expectancy changes with various combinations of Behavioral Migraine Management and migraine drug therapies.

Methods

Frequent migraine sufferers who failed to respond to 5 weeks of optimized acute migraine drug therapy were randomized to a 2 (Behavioral Migraine Management+, Behavioral Migraine Management−) × 2 (β-blocker, placebo) treatment design.

Results

Mixed models for repeated measures analyses (N = 176) revealed large increases in headache self-efficacy and internal headache locus of control and large decreases in chance headache locus of control with Behavioral Migraine Management+ that were maintained over a 12-month evaluation period. Chance headache locus of control and socioeconomic status moderated changes in headache self-efficacy with Behavioral Migraine Management+.

Conclusions

The “deficiency” hypothesis best explained how patient characteristics influenced changes in of headache self-efficacy with Behavioral Migraine Management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Studies that experimentally manipulate “perceived success” and/or other treatment elements (physiological learning) may provide information about change mechanisms, but have experimentally altered clinical treatment, and thus fail to provide information about changes in expectancies that occur when treatment is administered in the clinical setting [56–58].

All variables examined in the moderator analyses, other than ethnicity, are continuous variables. However, the terms “high” and “low” are used for readability.

The most recent clinical trials of preventative migraine medication tend to report dropout rates of 50% at 6 months. In contrast, the Treatment of Severe Migraine trial has a dropout rate of 35% at 10 months. Thus, crudely averaged over months, the dropout rate for the Treatment of Severe Migraine trial (≈3.5% per month) was less than half of the comparative dropout rate for other recent preventative medication trials (≈8% per month). Another way to compare dropouts across trials is to note that the dropout rate for the Treatment of Severe Migraine trial at 16 months is similar to the dropout rate for other recent trials at 6 months.

References

Nestoriuc Y, Martin A: Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: A meta-analysis. Pain. 2007, 128:111–127.

Penzien D, Rains J, Andrasik F: Behavioral management of recurrent headache: Three decades of experience and empiricism. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2002, 27:163–181.

Campbell J, Penzien D, Wall E: Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache: Behavioral and physical treatments. American Academy of Neurology Guidelines 2000. Retrieved May 03, 2010, from www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0089.pdf

Holroyd K, Penzien D: Pharmacological vs. nonpharmacological prophylaxis of recurrent migraine headache: A meta-analytic review of clinical trials. Pain. 1990, 42:1–13.

Silberstein S: Practice Parameter: Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2000, 55:754–762.

Bandura A: Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977, 84:191–215.

Bandura A: Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman, 1997.

Rotter JB: Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychol Monogr. 1966, 80:1–28.

Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K: Patient self management of chronic disease in primary care. JAMA. 2002, 288:2469–2475.

Marks R, Allegrante J, Lorig K: A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice. Health Promote Pract. 2005, 6:37–43.

Tobin D, Reynolds R, Holroyd K, Creer T: Self-management and social learning theory. In K. Holroyd and T. Creer (eds), Self-management of chronic disease: Handbook of clinical interventions and research. New York: Academic Press, 1986.

Rains J, Penzien D, Lipchik G: Behavioral facilitation of medical treatment for headache part II: Theoretical models and behavioral strategies for improving adherence. Headache. 2006, 46:1395–1403.

Nicholson RA, Hursey RG, Nash JM: Moderators and mediators of behavioral treatment for headache. Headache. 2005, 45:513–519.

Holroyd K, Penzien D, Rains J, Lipchik G, Buse D: Behavioral management of headaches. In S. Silberstein, R. Lipton and D. Dodick (eds), Wolff's Headache and Other Head Pain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2008, 721–746.

Holroyd K, Martin P: Psychological treatments for tension-type headache. In J. Olesen, P. Tfelt-Hansen and K. Welch (eds), The headaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000, 643–649.

French DJ, Holroyd KA, Pinnell C, et al.: Perceived self-efficacy and headache-related disability. Headache. 2000, 40:647–656.

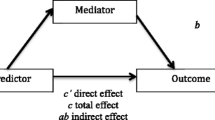

Holroyd KA, Labus J, Carlson BW: Moderation and mediation in the psychological and drug treatment of chronic tension-type headache: The role of disorder severity and psychiatric comorbidity. Pain. 2009, 143:213–222.

Rokicki LA, Holroyd KA, France CR, et al.: Change mechanisms associated with combined relaxation/EMG biofeedback training for chronic tension headache. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 1997, 22:21–41.

Nestoriuc Y, Rief W, Martin A: Meta-analysis of biofeedback for tension-type headache: Efficacy, specificity, and treatment moderators. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008, 76:379–396.

Holroyd KA, Malinoski PT, Carlson BW: Patient characteristics and treatment adherence predict response to antidepressant medication and to cognitive-behavior therapy for chronic tension-type headache. Ann. Behav. Med. 2002, 24:S050.

Nicholson R, Nash J, Andrasik: A self-administered behavioral intervention using tailored messages for migraine. Headache. 2005, 45:1124–1139.

Thorn BE, Pence LB, Ward LC, et al.: A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J Pain. 2007, 8:938–949.

Mizener D, Thomas M, Billings R: Cognitive changes of migraineurs receiving biofeedback training. Headache. 1988, 28:339–343.

Lee S, Park J, Kim M: Efficacy of the 5-HT1A agonist, buspirone hydrochloride, in migraineurs with anxiety: A randomized, prospective, parallel group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache. 2005, 45:7.

Martin NJ, Holroyd KA, Penzien DB: The headache-specific locus of control scale: Adaptation to recurrent headaches. Headache. 1990, 30:729–734.

Wallston KA: The Validity of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scales. J Health Psychol. 2005, 10:623–631.

Nicholson RA, Houle TT, Rhudy JL, Norton PJ: Psychological Risk Factors in Headache. Headache. 2007, 47:413–426.

Hollon SD, DeRubeis J: Placebo-psychotherapy combinations: Inappropriate representations of psychotherapy in drug-psychotherapy comparative trials. Psychol Bull. 1981, 90:467–477.

Cox DJ, Freundlich, A., Meyer, R.G.: Differential effectiveness of electromyograph feedback, verbal relaxation instructions, and medication placebo with tension headaches. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1975, 43:892–898.

Sotsky SM, Glass DR, Shea MT, Pilkonis PA, et al.: Patient predictors of response to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy: Findings in the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Am J Psychiatry. 1991, 148:997–1008.

Holroyd K, Cottrell C, O'Donnell F, et al.: Does Preventive (Beta Blocker) Medication, Behavioral Migraine Management or Their Combination Improve Outcomes of Optimal Acute Therapy in Frequent Migraine: A Randomized Trial. Submitted.

Holroyd K, Cottrell C, O'Donnell F, et al.: Does preventive medication, behavioral migraine management or their combination add to optimal acute therapy in the management of frequent migraines: The TSM trial. Headache. 2006, 46:835.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society: Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988, 8:1–96.

Holroyd K, Cottrell C, Echelberger-McCune R: Behavioral management for migraine headaches: A treatment program. Athens, OH: Ohio University Headache Treatment and Research Project, 2000.

Jhingran P, Osterhouse JT, Miller DW, Lee JT, Kirchdoerfer L: Development and validation of the migraine-specific quality of life questionnaire. Headache. 1998, 38:295–302.

Heckman BD, Holroyd KA, Tietjen G, et al.: Whites and African-Americans in headache specialty clinics respond equally well to treatment. Headache. 2009, 29:650–661.

Williams DR, Collins C: US socioeconomic and racial differences in health: Patterns and explanations Annu Rev Sociol. 1995, 21:349.

Leon AM, CH, Chuang-Stein C, Archibald D, Archer G, Chartier K: Attrition in randomized controlled clinical trials: Methodological issues in pyschopharmacology. Biol Psychiatry. 2006, 59:1001–1005.

Mallinckrodt C, Clark W, David S: Accounting for dropout bias using mixed-effects models. J Biopharm Stat. 2001, 11:9–21.

Mallinckrodt C, Clark W, David S: Type I error rates from mixed-effects model repeated measures versus fixed effects ANOVA with missing values imputed via last observation carried forward. Drug Inf J. 2001, 35:1215–1225.

Mallinckrodt C, Sanger T, Dube S, et al.: Assessing treatment effects in longitudinal data. Biol Psychiatry. 2003, 53:754–760.

Molenberghs G, Thijs H, Jansen I, Beunckens C: Analyzing incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data. Biostatistics. 2004, 5:445–464.

Barnes S, Mallinckrodt C, Lindborg S, Carter M: The impact of missing data and how it is handled on the rate of false-positive results in drug development. Pharm Statist. 2008, 7:215–225.

Gadbury G, Coffey C, Allison D: Modern statistical methods for handling missing data. Obes Rev. 2003, 4:175–184.

Lipchik G, Holroyd K, Nash J: Cognitive-behavioral management of recurrent headache disorders: A minimal-therapist contact approach. In D. Turk and R. Gatchel (eds), Psychological Approaches to Pain Management. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2002, 356–389.

Lipton R, Bigal M, Diamond M, et al.: Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007, 68:343–349.

Link BG, Phelan J: Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995, Spec No:80–94.

Brandes J: The migraine cycle: Patient burden of migraine during and between migraine attacks. Headache. 2008, 48:430–441.

Silberstein S, Freitag F, Bigal M: Migraine treatment. In S. Silberstein, R. Lipton and D. Dodick (eds), Wolff's Headache and Other Head Pain. London: Oxford University Press, 2008, 177–292.

Ramadan N, Silberstein S, Freitag F, Gilbert T, Frishberg B: Evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache in the primary care setting: Pharmacological management for the prevention of migraine. American Academy of Neurology Guidelines 2002. Retrieved Accessed May 03 2010, from http://www.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/gl0090.pdf

Steiner T, Paemeiere K, Jensen RV, D, et al.: European principles of management of common headache disorders in primary care. J Headache Pain. 2007, 8 S3–47.

pt?>Kaniecki RL, S: Treatment of primary headache: Preventive treatment of migraine. Standards of care for headache diagnosis and treatment. Chicago: National Headache Foundation, 2004, 40–52.

Brandes J, Saper J, Diamond M, et al.: Topiramate for migraine prevention. JAMA. 2004, 291:965–973.

Silberstein S, Neto W, Schmitt J, Jacobs D: Topiramate in migraine prevention: Results of a large controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2004, 61:490–495.

Diener H-C, Tfelt-Hansen P, Dahlof C, et al.: Topiramate in migraine prophylaxis: Results from a placebo-controlled trial with propranolol as an active control. J Neurol. 2004, 251:943–950.

French DJ, Gauthier JG, Roberge C, Nouwen A: Self-efficacy in the thermal biofeedback treatment of migraine sufferers. Beh Ther. 1997, 28:109–125.

Holroyd KA, Penzien DB, Hursey K, et al.: Change mechanisms in EMG biofeedback training: Cognitive changes underlying improvements in tension headache. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984, 52:1039–1053.

Blanchard EB, Kim M, Hermann C, et al.: The role of perception of success in the thermal biofeedback treatment of vascular headache. Headache Q. 1994, 5:231–236.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following people for their assistance in carrying out the TSM trial: Constance Cottrell, Francis O’Donnell, Gary Cordingley, Carol Nogrady, Kimberly Hill, Victor Heh, Suzanne Smith, Bernadette Devantes Heckman, Brenda Pinkerman, Gregg Tkachuk, Sharon Waller, Donna Shiels, Kathleen Darchuk, Yi Chen, Timur Skeini, Manish Singla, Swati Dalmai, Lori Arnott, and Lina Himawan. Support for this trial was provided by grant NS-32374 (awarded to Dr. Holroyd) from the National Institutes of Health. Merck Pharmaceuticals, Inc and GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals donated triptans (5-HT1B/D-agonists) for acute migraine therapy, which was their only involvement.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Ms. Seng reports no conflicts of interest. Dr. Holroyd has received support from the National Institutes of Health (NINDS; NS32375), has consulted for ENDO Pharmaceuticals and Takeda Pharmaceuticals North America, and received an investigator initiated grant from ENDO Pharmaceuticals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Dr. Holroyd has full control of all primary data from the TSM trial. All analyses were conducted by Ms Seng.

About this article

Cite this article

Seng, E.K., Holroyd, K.A. Dynamics of Changes in Self-Efficacy and Locus of Control Expectancies in the Behavioral and Drug Treatment of Severe Migraine. ann. behav. med. 40, 235–247 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9223-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9223-3