Abstract

This paper tries to combine the natural history model of social problems with Foucauldian discourse analysis. Foucault tried to outline connections between knowledge and power, and this paper applied his method to qualitative content analysis of discourse on low birth rates in Japanese news articles and discussions among the Japan’s national Diet members. This paper focuses on two topics: how some policies to combat low birth rates were adopted, while other were rejected; and why the policies which were adopted tend to favor two-income families. In order to answer these two questions, this paper selects seven important events from 1990 to 2016 in order to understand what kind of power or knowledge operates, and what kind of similarities in the discourse appear repeatedly and regularly. This paper highlights four points. First, claim-makers who regarded declining birth rates as a serious social problem---population experts, politicians, bureaucrats, and feminists---influenced political decisions against low birth rates. The low birth rate issues can be considered a government-manufactured social problem. Second, the policies against low birth rates have emphasized that difficulty in balancing work and childrearing decreases the fertility rates. Therefore, gender-equality and work-life balance have been dominant within the discourses on low birth rates, and the more fundamental problem of why young people are postponing marriage have been ignored. Third, both bureaucrats in the Ministry of Finance balancing national revenue and expenditure and feminist activists emphasizing gender-equality and work-life balance often reject a child allowance which provides equal benefit to each child regardless of the parents’ lifestyle. Fourth, merely welfare policies that are adaptive to the ideologies of gender-equality and work-life balance have been implemented. Bureaucrats, lawmakers, and feminist activists gained ownership of a social problem. Similarly, the gender-equality ideology has only catered to heterosexual males and females who form a family, work outside, and raise children equally. Therefore, single persons with no family or singleincome families have been neglected. This should be described as the exertion of governmental power.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Another fruitful natural history model of social problem process is proposed by Joel Best (2016). Best lists six stages: Claimsmaking, Media Coverage, Public Reaction, Policymaking, Social Problems Work, and Policy Outcomes (Best ibid.:19). The model can focus on broad and macro structures, including social contexts and settings in which claim-making activities occur. This paper especially focuses on Policymaking, Media Coverage and Public Reaction because low birth rate issues in Japan are primarily claimed by population experts, policymakers, and media workers that follow them. Most Public Reactions are declined to be influenced by other stages.

This paper takes context constructionism stance proposed by Joel Best and Lawrence Nichols (Best 2016; Nichols 2015). As Nichols suggests, this paper accepts that contexts are constructed by claims-makers and social science analysts through their definitional ‘context work’ and, therefore, truths are complex and paradoxical (Nichols ibid., pp.82–4). In this paper, the causes of low birth rates to which claims-makers and analysts attribute are examples of contexts. Some might be correct, and others might be not from statistical and scientific point of view. The author of this paper takes the stance that analysts including the author can reasonably judge which causes are justifiable, and others are ‘distorted’ or not. By taking the stance, context constructionism can develop further research questions: some figures and/or statistics are distorted. And even so, how and why such ‘distorted’ figures or statistics can be prevalent in the social problem process.

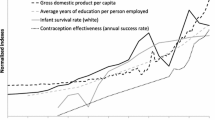

For instance, a Japanese economic demographer Yamaguchi Mitoshi argued that female labour participation along with their higher education decreased birth rates using longitudinal data between 1900 and 1970 (Yamaguchi 2001).

Akagawa (2004, p. 94) picks up ten well-known Japanese feminists, economists and bureaucrats between 2000 and 2004, who argued that gender equality causes higher birth rates among advanced countries.

In this section, the author of this paper has appeared as a claimsmaker on low birthrate issues in Japan. As a claimsmaker, the author challenged the diagram above and the discourse that gender-equality is related to low birthrates. However, in this paper, the author tries to analyze himself as an object of the research, in other words, as one of the claimsmakers in this issue. This reflexive analysis has been recommended by Kitsuse and Spector (1977, p.127).

A “society in which all citizens are dynamically engaged” is one of the key slogans of the Shinzo Abe administration.

According to Financial Times Lexicon, Abenomics is “the name given to a suite of measures introduced by Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe after his December 2012 re-election to the post he last held in 2007. His aim was to revive the sluggish economy with “three arrows”: a massive fiscal stimulus, more aggressive monetary easing from the Bank of Japan, and structural reforms to boost Japan’s competitiveness” (http://lexicon.ft.com/Term?term=abenomics).

References

Abe, S. (2016a). A remark at the 17 th Budget Committee in the 190th House of Representative (第190回国会・衆議院・予算委員会17号), February, 29.

Abe, S. (2016b). A remark at the 10 th plenary session of the 190th House of Councilors (第190回国会・参議院・本会議), March, 7.

Akagawa, M. (2004). What’s wrong with a low birthrate on earth! (子どもが減って何が悪いか!). Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo (筑摩書房).

Akagawa, M. (2005). Stop praying to increase birthrate. We have to redesign the system. Tokyo:Chuo Koron (中央公論), 120 (6), 126–135.

Akagawa, M. (2011). Is a shrinking population really a social problem? SSSP 2011 Annual Meeting Session 94: 2011.8.21 at Harrah's Las Vegas Hotel.

Akagawa, M. (2012). A Sociology of social problems (少子化問題の社会学). Tokyo: Kobundo(弘文堂).

Akagawa, M. (2014). The construction and transformation of low birth rate issues in Japan since 1990s. Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) Annual Meetings, 139.

An Anonymous Woman (2016). Hoikuen Ochita Nihon Shine!!! (保育園落ちた。日本死ね!!!).https://anond.hatelabo.jp/20160215171759 Accessed 2nd April 2019.

Best, J. (2015). Beyond case studies: Expanding the constructionist framework for social problems research. Qualitative Sociology Review, 11(2), 18–33.

Best, J. (2016). Social problems (3rd ed.). New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Foucault, M. (1972). The archeology of knowledge. London and New York: Routledge.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon Press.

Foucault, M. (1994 [1968]). Réponse à une question. Esprit, 371, 850–874. In Defert, D. & Evald, F. (eds.) Dits et écrits (1954–1988), tome I: 1954–1975, Gallimard. 673–695.

Foucault, M. (2000). The subject and power in J. Faubion (ed.) Power, trans., R. Hurley et al., New York: New Press.

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, territory, population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978, trans., G. Burchell, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gula, R. J. (2002). Non-sense: A handbook of logical fallacies. Virginia: Axios Press.

Gusfield, J. R. (1981). The culture of public problems: Drinking, driving and the symbolic order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Huffington Post. (2016). The most important for women. March 11 (https://www.huffingtonpost.jp/2016/03/11/the-most-important-for-women_n_9443990.html, )Accessed 2nd April 2019

Iwasawa, M. (2015). Declining marriage rate and change in couples which lead to declining birth rates. In Takahashi, S. & H. Obuchi (Eds.), Shrinking population and policy against low birth rate: Library in demography(人口減少と少子化対策). Tokyo: Hara Shobo (原書房).

Japan Times (2016). Blog rant sparks movement for better day care. February 17, p. 4.

Keller, R. (2012). Entering discourses: A new agenda for qualitative research and sociology of knowledge. Qualitative Sociology Review, 8(2), 46–55.

Keller, R. (2013). Doing discourse research: An introduction for social scientists. London: Sage.

Kendall, G., & Wickham, G. (1999). Using Foucault’s methods. London: Sage.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nichols, L. T. (2015). Contextual understanding in constructionism: A holistic, dialogical model. Qualitative Sociology Review, 6(2), 76–92.

Sato, M., & Miyake, K. (2016). Great transformation of world history (世界史の大転換). Tokyo: PHP Publishing Company (PHP出版社).

Shimbun, Asahi. (1990a). Tag of war on the revision of child allowance (児童手当の見直しで綱引き). November 13.

Shimbun, Yomiuri. (1990b). Female higher education declines birth rates(女性高学歴化で出生率低下). July 13.

Shimbun, Yomiuri. (1990c). Investigate falling birthrates: Accelerate improving child-bearing environment(検証 出生率低下 産める環境作り急務). August 29.

Shimbun,Asahi. (2006). Opposition to the ministry Inoguchi by six experts: Improvements in the childrearing environment rather than financial support (少子化対策、猪口氏に異論 6専門委員、抗議声明へ 「経済支援より環境整備」). May 21.

Shimbun, Asahi. (2009a). Issues in Japan: New allowance or free child-care service for infants? (にっぽんの争点: 子育て 新「手当」か幼児無償化か). August 18.

Shimbun, Asahi. (2009b). Eliminating the waiting list for children rather than child allowance (子ども手当より「待機児童解消を」OECDが政策提言). November 18.

Special committee on a low birthrate and gender equality. (2005). International comparative report on social circumstances as to low birth rate and gender equality(少子化と男女共同参画に関する社会環境の国際比較報告書). Tokyo: Gender equality bureau, Cabinet Office(内閣府男女共同参画局).

Spector, M., & Kitsuse, J. I. (1977). Constructing social problems. California: Cummings Publishing Company.

Takayama, N. & Harada, Y. (1993). Finance and Savings in the ageing society (高齢化の中の金融と貯蓄). Tokyo: Nihon Hyouron Sha (日本評論社).

Walters, W. (2012). Governmentality: Critical encounters. London: Routledge.

Yamaguchi, M. (2001), Population growth and economic development(人口成長と経済発展). Tokyo: Yuhikaku (有斐閣).

Yamatani, Y. (2005). A remark at the 2nd committee on aging society in the 163th house of councilors in Japan(第163回国会・参議院・少子高齢社会に関する調査会). October, 26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Akagawa, M. A Natural History Model of Low Birth Rate Issues in Japan since the 1990s. Am Soc 50, 300–314 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-019-9404-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12108-019-9404-x