Abstract

Purpose

Immunotherapy-based approaches are standard first-line treatments for advanced/metastatic lung cancer or for chemoradiotherapy consolidation in locally advanced disease. Uncertainty on how to treat patients at disease progression prompted us to develop a consensus document on post-immunotherapy options in Spain for patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma.

Methods

After extensive literature review, a 5-member scientific committee generated 33 statements in 4 domains: general aspects (n = 4); post-durvalumab in locally advanced disease (n = 6); post-first-line immunotherapy ± chemotherapy in advanced/metastatic disease (n = 11); and post-first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced/metastatic disease (n = 12). A panel of 26 lung cancer experts completed 2 Delphi iterations through an online platform rating their degree of agreement/disagreement (first-round scale 1–5 and second-round scale 1–4, 1 = strongly disagree, 4/5 = strongly agree) for each statement. Second-round consensus: ≥ 70% of responses were in categories 1/2 (disagreement) or 3/4 (agreement).

Results

Consensus was reached for 2/33 statements in the first Delphi round and in 29/31 statements in the second round. Important variables informing treatment at disease progression with an immunotherapy-based treatment include: disease aggressiveness, previous treatment, accumulated toxicity, progression-free interval, PD-L1 expression, and tumour mutational burden. A platinum-based chemotherapy should follow a first-line immunotherapy treatment without chemotherapy. Treatment with docetaxel + nintedanib may be appropriate post-durvalumab in refractory patients or following progression to first-line chemotherapy + immunotherapy, or second-line chemotherapy after first-line immunotherapy, or first-line chemotherapy in some patients with low/negative PD-L1 expression, or second-line immunotherapy after first-line chemotherapy.

Conclusions

To support decision making following progression to immunotherapy-based treatment in patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma, a consensus document has been developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treatment landscape has completely changed with the coming of age of immunotherapy. The past decade has seen great advances in the treatment of patients with advanced lung cancer, with the first clinically relevant improvements in overall survival (OS) occurring in the later lines of treatment followed by significant advances in the first-line setting that have upended the treatment algorithm [1].

Upon progression to a platinum chemotherapy doublet, docetaxel or pemetrexed monotherapy was standard regimen for patients with advanced NSCLC. The addition of an anti-angiogenic agent (ramucirumab or nintedanib) to docetaxel increased OS in patients with lung adenocarcinoma who had progressed following first-line chemotherapy [2, 3]. The greatest survival improvement and reduction of tumour volume were reported in patients with particularly poor prognosis who rapidly progressed while receiving first-line chemotherapy and who had a larger tumour volume [4,5,6].

Also, in the post-chemotherapy setting, treatment with immunotherapy agents targeting PD-1/PD-L1 increased survival compared with docetaxel monotherapy, as second-line treatment (nivolumab) [7, 8], and as second- and third-line treatments (pembrolizumab and atezolizumab) [9,10,11,12]. Higher PD-L1 tumour expression correlated with a better outcome to immunotherapy in patients with adenocarcinoma [7,8,9,10, 12]. Analyses requested by the European regulatory authorities for nivolumab reported a greater risk of early mortality when receiving nivolumab compared with docetaxel in the group of patients with adenocarcinoma histology, rapid progression/refractoriness to a first-line chemotherapy, ECOG performance status (PS) 1, and low PD-L1 expression [13]. Similar analyses are not available for pembrolizumab or atezolizumab.

The greater effectiveness of immunotherapy conditioned by PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden (TMB) [14, 15] and the better outcomes in patients with rapid progression to first-line chemotherapy observed with anti-angiogenic agents in combination with docetaxel [2,3,4] appear to indicate that both therapeutic approaches could be complementary. Of note, there have been no randomized clinical trials directly comparing single-agent immunotherapy with the combination of an anti-angiogenic agent and docetaxel; cross-trial comparisons have been performed using the control arm of docetaxel monotherapy. This suggests that post-chemotherapy treatment and its subsequent therapeutic sequence require careful consideration.

On the other hand, several immunotherapy trials reported in 2017 and 2018 transformed the first-line treatment of metastatic NSCLC [1]. The preferred first-line treatment option for patients without targetable mutations is now an immunotherapy-based regimen alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

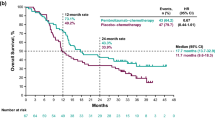

In patients with tumour PD-L1 expression ≥ 50%, the first-line recommendation is pembrolizumab alone, based on the KEYNOTE-024 Phase 3 study reporting a significant improvement in OS with pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy [after median follow-up of 25.2 months, median OS [mOS] of 30.0 months with pembrolizumab, and 14.2 months with chemotherapy, HR 0.63 (95% CI 0.47–0.86)] [16, 17].

Pembrolizumab alone may also be an alternative for patients with PD-L1 expression of 1–49% who cannot receive chemotherapy, based on a significant improvement in OS with pembrolizumab compared with chemotherapy in the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-042 trial in patients with tumour PD-L1 expression of ≥ 1% [after median follow-up of 14 months, mOS of 16.4 months vs. 12.1 months, HR 0.82 (95% CI 0.71–0.93)] [18, 19]. However, this improvement in the overall population appeared to be driven by patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 50% (mOS of 20.0 months vs. 12.2 months [HR 0.70 (95% CI 0.58–0.86)]), representing 47% of the overall population [18, 19].

The Phase 3 CheckMate 227 trial evaluating first-line ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4) plus nivolumab vs. platinum-based chemotherapy met its co-primary endpoint of significantly prolonging PFS in patients with NSCLC with high TMB, defined as ≥ 10 mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) [15]. Median PFS (mPFS) in the immunotherapy combination arm was 7.2 months compared with 5.5 months (HR 0.58 [97.5% CI 0.41–0.81]; p < 0.001). This PFS benefit in the high TMB population was observed irrespective of PD-L1 expression. Preliminary results indicated a tendency toward improved OS in the high TMB population treated with the immunotherapy combination with a mOS of 23.0 months compared with 16.4 months in patients receiving chemotherapy [HR 0.79 (95% CI 0.56–1.10)] [20].

Four randomized studies in patients with non-squamous NSCLC showed that the addition of a PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor to standard chemotherapy is superior to standard chemotherapy alone.

In patients without targetable mutations, first-line pembrolizumab in combination with platinum–pemetrexed was more effective than chemotherapy alone [21, 22]. In the Phase 3 KEYNOTE-189 trial of non-squamous NSCLC, OS improved in the pembrolizumab/chemotherapy arm compared with the chemotherapy alone arm (with 18.7-month median follow-up, mOS was 22.0 months vs. 10.7 months [HR 0.56 (95% CI 0.45–0.70); p < 0.00001) [23]. The OS benefit obtained with pembrolizumab/chemotherapy was independent of PD-L1 expression and was also reported in patients with tumors with PD-L1 < 1% [HR 0.52 (95% CI 0.36–0.74)]. The co-primary endpoint of PFS also improved in the pembrolizumab arm.

Three Phase 3 studies of atezolizumab also showed survival improvement independently of PD-L1 expression. In IMpower150 in patients with non-squamous NSCLC, both OS and PFS improved in the four-drug combination arm of atezolizumab plus carboplatin paclitaxel and bevacizumab (ACPB) compared with a control chemotherapy arm without atezolizumab; mOS of 19.2 months was reported in the atezolizumab arm compared with 14.7 months in the control arm (HR 0.78 [95% CI 0.64–0.96]; p = 0.02) [24]. IMpower130 evaluated atezolizumab plus carboplatin and nab-paclitaxel vs. a control chemotherapy arm without atezolizumab. OS similarly improved in the atezolizumab arm, with a mOS of 18.6 months compared with 13.9 months in the control arm (HR 0.79 [95% CI 0.64–0.98]; p = 0.033) [25]. IMpower132 evaluated the combination of atezolizumab plus carboplatin or cisplatin with pemetrexed vs. a control chemotherapy arm without atezolizumab in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC. PFS improved in the atezolizumab arm [mPFS 7.6 vs. 5.2 months (HR 0.6; 95% CI 0.49–0.72; p < 0.0001)], but the improvement in OS did not reach statistical significance [mOS 18.1 vs. 13.6 months (HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.64–1.03; p = 0.0797)], albeit not being fully mature [26].

Consolidation immunotherapy with durvalumab following chemoradiotherapy significantly improved the outcome of patients with locally advanced, inoperable Stage III NSCLC in the Phase 3 PACIFIC study evaluating durvalumab vs. placebo [27, 28]. OS and PFS were both significantly prolonged in the durvalumab arm compared with the placebo arm [OS HR 0.68 (99.73% CI 0.47–0.997); p = 0.0025 and mPFS 17.2 vs. 5.6 months, HR 0.51 (95% CI 0.41–0.63)].

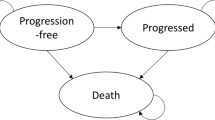

These clinical trials changed the treatment algorithm of patients with advanced wild-type EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and BRAF lung adenocarcinoma. Immunotherapy-based regimens are standard first-line treatments for advanced disease or for chemoradiotherapy consolidation in locally advanced disease. It is important to note that all clinical trials were performed using a control arm that is no longer considered a standard regimen and all second-line trials enrolled an immunotherapy-naïve patient population that no longer exists. Consequently, there is great uncertainty in the clinic as to how to best treat patients who progress after receiving immunotherapy. The new therapeutic scenario that results from great advances in the standard of care, although having the potential to bring the best outcomes to patients for upfront treatment, does not address the best treatment to administer upon progressive disease. There is a need to optimize the sequential treatment of currently available regimens to further improve the survival outcome of patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma [1].

For issues that frequently occur in routine clinical practice, but for which there is not enough evidence, a systematic approach that aims to generate a consensus among experts can provide reliable guidance. The Delphi technique is commonly used to develop guidelines with health professionals [29]. The Delphi process allows panelists to reach an agreement by iteratively urging them to consider a series of problematic issues about key health decisions in conditions of low-grade evidence and is considered an appropriate tool to measure agreements and delineate therapeutic options for advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma beyond the first-line setting.

Materials and methods

Objectives

We aimed to develop a consensus document using the Delphi technique on treatment options in Spain beyond the first-line setting for patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma without targetable mutations (wild-type EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and BRAF). An external expert in Delphi methodology guaranteed the quality of the overall process.

Study design

Scientific committee

In April 2018, a scientific committee of five experts in comprehensive lung cancer management met to define and lead this consensus project. The following steps were carried out by the scientific committee: (1) selection of expert panel; (2) generation of clinical statements based on the extensive narrative review of the current medical literature; (3) definition of the consensus levels and agreement on methodology; (4) interpretation of the results from the Delphi rounds; (5) final wording in the consensus document.

Expert panel

A panel of 26 medical oncologists specialized in lung cancer and renowned for their clinical and research experience were selected by the scientific committee. In this selection of an expert panel, a balanced territorial representation of Spain was considered.

Delphi

Generation of statements

After an extensive narrative literature review, 33 statements belonging to 4 major domains were drafted by the scientific committee. These domains covered general aspects and three clinical scenarios according to disease stages and treatment line:

- 1.

General aspects of the current treatment of advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma (four statements)

- 2.

Durvalumab as consolidation therapy after platinum-based chemoradiotherapy: impact on subsequent treatment lines (six statements)

- 3.

First-line immunotherapy ± chemotherapy: impact on optimal treatment sequencing in second- and further treatment lines (11 statements)

- 4.

Treatment after platinum-based chemotherapy without immunotherapy: options and optimal therapeutic sequencing (12 statements)

It was established that these statements would be evaluated in patients with wild-type lung adenocarcinoma with a good general condition (ECOG PS 0–1) without contraindications to any type of treatment. Non-immunotherapy treatment regimens included in the statements were limited to those approved and reimbursed by the Spanish National Health System. These prerequisites were included to simplify the interpretation and allow for a better clinical applicability of any consensus.

Consensus levels

The expert panel completed two Delphi rounds of the statements through an online platform. In the first round, the 26 panelists voted using the following answers: (1) “strongly disagree”; (2) “basically disagree”; (3) “doubtful”; (4) “basically agree”; and (5) “strongly agree”. A consensus existed if ≥ 70% of the responses were classified as “strongly agree” or “strongly disagree”. If the consensus was 100%, it was considered “unanimous”. All statements reaching consensus in the first round did not undergo the second Delphi round. The statements that had ≥ 15% of “doubtful” responses were reassessed by the scientific committee, to discern if this was due to the ambiguity of the statement itself, in which case it was reformulated, or due to the issue being controversial in itself, in which case the statement remained unchanged in the second Delphi round.

A second Delphi round was held for all statements without consensus in the first round. In this second round, the following answers were available: (1) “strongly disagree”; (2) “basically disagree”; (3) “basically agree”; and (4) “strongly agree”. The reduction to four answers in this second round is contemplated in the Delphi methodology to prompt experts to decide in favour or against a statement and avoids the tendency to give a neutral answer. A consensus was defined if ≥ 70% of the responses were in categories 1 and 2 (consensus in the disagreement) or in categories 3 and 4 (consensus in the agreement), and the consensus was considered unanimous if 100% was reached in either of the two categories. A majority was defined when the percentage of agreement or disagreement was ≥ 60% but < 70%. A dissent was defined as < 60% agreement.

All 26 panelists responded to both Delphi rounds. The first round took place from 11 July 2018 to 21 August 2018 and the second round took place from 7 September 2018 to 17 October 2018. This study consisted of a survey of expert opinions and no patient data were collected, so no specific independent ethical or research review or approval was necessary.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and ordinal variables were summarized with counts and percentages tabulated by round. The SPSS v25 (IBM) program package was used for the statistical analyses.

Development of the consensus manuscript

All five members of the scientific committee wrote the consensus manuscript, which was then enriched with feedback from three external experts (Enriqueta Felip, Pilar Garrido, and Luís Paz-Ares).

This project began in April 2018 and ended in March 2019. During this time and when this article was drafted, newly published literature and congress presentations were reviewed to analyze the clinical implications of any new data in patients with advanced NSCLC and to provide support for the consensus statements.

Results

In the first Delphi round, 33 statements were evaluated, and a consensus was reached for 2 statements (6%). In the second Delphi round, the remaining 31 statements were evaluated, including 1 statement that had been reformulated: in 7 statements, there was unanimity in the agreement and in 22 statements, there was consensus in the agreement (overall consensus: 94%). For one statement, there was majority in disagreement and in one statement, there was dissent.

General aspects of the current treatment of advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma

Table 1 shows the responses for the four statements in this domain. There was a high degree of consensus (92–100%) on the fact that the incorporation of new highly effective immunotherapy-based treatments as first-line treatment of advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma has generated uncertainty regarding optimal treatment upon disease progression. It is not possible to generate high-level scientific evidence because the second-line Phase 3 studies leading to regulatory approvals will not be repeated with patient populations that have received the current standard of first-line immunotherapy. In this case, expert opinion and clinical experience are necessary to define what is the best therapeutic sequence to offer patients who have reported disease progression.

Durvalumab as consolidation therapy after platinum-based chemoradiotherapy in Stage III wild-type lung adenocarcinoma: impact on subsequent treatment lines

Table 2 shows the responses for the six statements in this domain. There was high agreement (85–96%) that the following variables may define the optimal regimens to be administered upon progression to durvalumab in the locally advanced setting: progression-free interval, clinical aggressiveness of the progression (early progression and high symptomatic tumour load), accumulated toxicity from previous treatments, tumour PD-L1 expression, and TMB.

Patients treated with platinum-based chemoradiotherapy progressing during durvalumab consolidation, can be classified as refractory to platinum when the interval from the end of chemoradiotherapy to progression is less than 6 months. For this reason, the combination of docetaxel and nintedanib could be an appropriate therapeutic option. If this disease-free interval is longer than 12 months, during treatment with durvalumab or when it has already ended, a platinum-based chemotherapy would be an appropriate therapeutic option. If the interval is between 6 and 12 months, the decision could be based on the proximity to 6 vs. 12 months, the clinical aggressiveness of the progression (high symptomatic tumour burden) and reports of previously accumulated toxicity.

There is not much evidence that rechallenging patients with immunotherapy-based treatment is effective [30,31,32]. Moreover, there is no evidence for rechallenging patients after chemoradiotherapy consolidation with durvalumab, so patients should be encouraged to participate in clinical trials. In any case, an immunotherapy rechallenge might be justified with a longer interval between the end of durvalumab and the progression of the disease and with higher tumour PD-L1 expression and high TMB.

First-line immunotherapy ± chemotherapy in advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma: impact on optimal treatment sequencing in second- and further treatment lines

Table 3 shows the responses for the 11 statements in this domain. A high degree of consensus (88–100%) was established, confirming the overall acceptance that new first-line immunotherapy-based treatments in routine clinical practice will reduce its use in later lines. There was a shared concern for the resulting economic impact.

After progression to first-line platinum, pemetrexed, and pembrolizumab, the administration of docetaxel and nintedanib may be the most appropriate therapeutic option. After progression to first-line carboplatin, paclitaxel, bevacizumab, and atezolizumab, the combination of docetaxel and nintedanib could be a therapeutic option. Single-agent pemetrexed is also a reasonable therapeutic option as it has demonstrated efficacy in the second-line setting, but with a more favourable safety profile than docetaxel alone [33] and may be a preferred option for disease with low aggressiveness. In patients experiencing early disease progression to first-line treatment and/or a high symptomatic tumour load, the combination of docetaxel and nintedanib may be more appropriate. On the other hand, after progression to a first-line immunotherapy regimen without chemotherapy, the most appropriate second-line therapeutic option would be platinum-based chemotherapy.

Upon progression to second-line platinum-based chemotherapy after first-line immunotherapy, a third-line regimen should consider treatment with the combination of docetaxel and nintedanib, or single-agent docetaxel or pemetrexed. The following variables are important when selecting third-line treatment: previous treatments, aggressiveness of disease progression (early progression and a high symptomatic tumour load), and accumulated toxicity. Higher aggressiveness of the disease would favour the use of the docetaxel and nintedanib combination.

In this clinical context, there is no scientific evidence that the reintroduction of an immunotherapy-based treatment is effective, so it should be considered only in a clinical trial setting.

Treatment after platinum-based chemotherapy without immunotherapy in advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma: options and optimal therapeutic sequencing

Table 4 shows the responses for the 12 statements in this domain. A high degree of consensus was attained in 10 of the 12 statements (88–100%). One statement required reformulation, one statement had a majority in disagreement, and one statement was in dissent; reflecting the uncertainties of treating patients in this clinical scenario.

Statement 1 (“tumour PD-L1 expression is a fundamental criterion to help therapeutic decision making in a patient previously treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy”) obtained a high proportion of “doubtful” responses (23.1%) in the first Delphi round. The scientific committee considered that the word “fundamental” could lead to confusion, so it was eliminated in the second Delphi round, achieving consensus.

The following variables should be considered when deciding second-line treatment after a first-line chemotherapy regimen: aggressiveness of disease progression (early progression and a high symptomatic tumour load), tumour PD-L1 expression, previous treatment, and accumulated toxicity from previous treatments.

In patients with aggressive disease progression with low or negative tumour PD-L1 expression, the combination of docetaxel and nintedanib could be a reasonable therapeutic option as a second-line treatment. On the other hand, second-line immunotherapy could be a reasonable therapeutic alternative in patients with a negative or unknown tumour PD-L1 expression in patients with slow disease progression.

At the time of progression to second-line immunotherapy, the third-line combination of docetaxel and nintedanib can be considered. Similarly, after a progression to second-line chemotherapy, the administration of third-line immunotherapy should be evaluated considering the aggressiveness of the progression to previous chemotherapy and tumour PD-L1 expression.

Statement 9 (“upon progression to second-line chemotherapy [docetaxel and nintedanib, docetaxel alone, or pemetrexed alone], one could consider administering immunotherapy as third-line treatment, but exclusively in patients with positive tumour PD-L1 expression”) obtained a majority in disagreement (61.5%). The point of disagreement was interpreted to be related to “exclusively patients with positive tumour PD-L1 expression”. If the disease progression to a second-line chemotherapy was not aggressive, the administration of third-line immunotherapy could be evaluated independently of tumour PD-L1 expression.

Statement 12 (“in a patient with negative tumour PD-L1 expression treated with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy plus bevacizumab attaining a disease control greater than 18 months, one could consider administering a second-line anti-angiogenic therapy [docetaxel and nintedanib] because of the benefit from the previous antiangiogenic”) obtained a dissent (42% disagree vs. 58% agree). Experts who frequently use a first-line combination of chemotherapy with bevacizumab to achieve a prolonged PFS, especially when tumour PD-L1 expression is negative, prefer to continue treatment at the time of progression with an anti-angiogenic with a different mechanism of action, such as the combination of docetaxel and nintedanib [34]. On the other hand, experts without extensive experience with bevacizumab value that when such a prolonged PFS is obtained with first-line chemotherapy, the most reasonable therapeutic option in the second-line setting is immunotherapy regardless of the negative tumour PD-L1 expression. The results from the LUME-Lung 1 study of docetaxel and nintedanib in patients with advanced NSCLC support the efficacy in all patients with adenocarcinoma; however, there is lower benefit in long-term progressors, particularly those patients who progressed at least 12 months after initiation of first-line therapy.

Discussion

The current Delphi study shows that a high degree of consensus exists among experts on how standard first-line immunotherapy-based regimens may be affecting decisions regarding subsequent treatment of patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma. This consensus document complements the information in the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO), Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica (SEOM), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and other guidelines [35,36,37], and aims to provide oncologists with a specific therapeutic decision process to optimize management of patients when their disease has progressed after receiving immunotherapy.

As the treatment of NSCLC further evolves, it is important to note that the following relevant scientific information was communicated after the second Delphi round took place:

- 1.

The use of durvalumab as a consolidation therapy after platinum-based chemoradiotherapy was limited by the European Medicine Agency (EMA) to patients with tumours expressing PD-L1 ≥ 1%. This restriction is a cause for concern among experts as it is judged to be based on non-robust analysis [38].

- 2.

In an updated analysis of CheckMate 227 trial, differences in OS between the nivolumab and ipilimumab arm and the chemotherapy arm were not statistically significant in the subgroup of patients with TMB ≥ 10 mut/Mb, with a HR of 0.77 (95% CI 0.56–1.06) [39].

- 3.

Two Phase 3 first-line studies of atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in non-squamous NSCLC reported improved PFS outcomes compared with the control arms [25, 26]. OS improved in one study [25], but not the other one, although not being yet fully mature [26].

After careful analysis of this new information, the scientific committee agreed that, despite its relevance, it did not affect the consensus statements or the elaboration of this document.

Although this consensus document aims to help therapeutic decision making, it has several limitations. First, this Delphi project has been developed under the premise of patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma with a good general condition (ECOG PS 0 and 1) and without medical contraindications. This may limit the potential applicability of the Delphi consensus to all patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma. This consensus document has been generated due to the lack of scientific evidence and with the realistic assumption that completed Phase 3 studies will not be repeated in a population that has received immunotherapy. We would encourage to use this document to help stimulate discussion on future real-world studies that could be carried out to support or question the consensus statements.

Several studies have suggested that treatment with immunotherapy does not condition the efficacy of subsequent chemotherapy. On the contrary, these studies seem to suggest an increase in the efficacy of chemotherapy [40,41,42,43,44], particularly when combined with anti-angiogenic agents [45,46,47], when administered after treatment with immunotherapy. Synergistic activity in both preclinical [48, 49] and clinical models [21, 22, 25, 26] support a hypothesis of a possible chemosensitization after prior exposure to immunotherapy. The changes induced by prior immunotherapy, as well as the “prolonged tissue half-life” of immunotherapy agents [50], could increase the efficacy of chemotherapy. The efficacy of chemotherapy in this setting, may be further increased when combined with an anti-angiogenic agent [51, 52].

There is little scientific evidence that rechallenging patients with immunotherapy-based treatment is effective [30,31,32]. Currently, immunotherapy rechallenge should be considered only in the setting of a clinical trial.

In summary, due to the lack of scientific evidence, a panel of experts has developed a consensus document via a Delphi process that can help therapeutic decision making for the optimal management of second-line treatment as well as subsequent treatment lines of patients with advanced wild-type lung adenocarcinoma. These decisions should carefully evaluate previous treatment(s) administered and the PFS obtained, aggressiveness of the disease progression (early progression and a high symptomatic tumour burden), accumulated toxicity, tumour PD-L1 expression, and TMB (Table 5). We hope that dedicated research efforts can generate missing real-world evidence to fill data gaps in the clinical frameworks covered in this consensus document.

References

Martinez P, Peters S, Stammers T, Soria JC. Immunotherapy for the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-3904.

Reck M, Kaiser R, Mellemgaard A, Douillard JY, Orlov S, Krzakowski M, et al. Docetaxel plus nintedanib versus docetaxel plus placebo in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (LUME-Lung 1): a phase 3, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(2):143–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70586-2.

Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, Prabhash K, Syrigos KN, Goksel T, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9944):665–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60845-X.

Gottfried M, Bennouna J, Bondarenko I, Douillard JY, Heigener DF, Krzakowski M, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib plus docetaxel in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: complementary and exploratory analyses of the phase III LUME-lung 1 study. Target Oncol. 2017;12(4):475–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-017-0517-2.

Reck M, Garassino MC, Imbimbo M, Shepherd FA, Socinski MA, Shih JY, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy for patients with aggressive or refractory advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the second-line setting. Lung Cancer. 2018;120:62–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.03.025.

Reck M, Mellemgaard A, Novello S, Postmus PE, Gaschler-Markefski B, Kaiser R, et al. Change in non-small-cell lung cancer tumor size in patients treated with nintedanib plus docetaxel: analyses from the Phase III LUME-Lung 1 study. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:4573–82. https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S170722.

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, Spigel DR, Steins M, Ready NE, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1627–39. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1507643.

Horn L, Spigel DR, Vokes EE, Holgado E, Ready N, Steins M, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: two-year outcomes from two randomized, open-label, phase III trials (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35):3924–33. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.74.3062.

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW, Felip E, Perez-Gracia JL, Han JY, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10027):1540–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01281-7.

Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(21):2018–28. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1501824.

Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M, Kowanetz M, Vansteenkiste J, Mazieres J, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (POPLAR): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10030):1837–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00587-0.

Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, Park K, Ciardiello F, von Pawel J, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10066):255–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32517-X.

Commmitee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). European Medicines Agency Assessment report of Opdivo. EMA/246304/2016. 2016.

Carbone DP, Reck M, Paz-Ares L, Creelan B, Horn L, Steins M, et al. First-line nivolumab in stage IV or recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2415–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1613493.

Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson GA, Audigier-Valette C, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in lung cancer with a high tumor mutational burden. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2093–104. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801946.

Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1823–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606774.

Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Updated analysis of KEYNOTE-024: pembrolizumab versus platinum-based chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score of 50% or greater. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(7):537–46. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.00149.

Lopes G, Wu Y-L, Kudaba I, Kowalski D, Cho BC, Castro G et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) versus platinum-based chemotherapy (chemo) as first-line therapy for advanced/metastatic NSCLC with a PD-L1 tumor proportion score (TPS) ≥ 1%: open-label, phase 3 KEYNOTE-042 study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(18_suppl):abstr LBA4. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.18_suppl.LBA4.

Mok TSK, Bondarenko I, Kubota K, Caglevic C, Karaszewska B, Penrod J et al. 102OFinal analysis of the phase III KEYNOTE-042 study: pembrolizumab (Pembro) versus platinum-based chemotherapy (Chemo) as first-line therapy for patients (Pts) with PD-L1–positive locally advanced/metastatic NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(Supplement_2):abstract 102O. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz063.

Hellmann MD, Ciuleanu TE, Pluzanski A, Lee JS, Otterson G, Audigier-Valette C et al. Nivolumab (nivo) + ipilimumab (ipi) vs platinum-doublet chemotherapy (PT-DC) as first-line (1L) treatment (tx) for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): initial results from CheckMate 227. Cancer Res. 2018;78(13 Suppl):Abstr CT077 and oral presentation. https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.Am2018-ct077.

Gandhi L, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801005.

Langer CJ, Gadgeel SM, Borghaei H, Papadimitrakopoulou VA, Patnaik A, Powell SF, et al. Carboplatin and pemetrexed with or without pembrolizumab for advanced, non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, phase 2 cohort of the open-label KEYNOTE-021 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(11):1497–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30498-3.

Gadgeel SM, Garassino MC, Esteban E, Speranza G, Felip E, Hochmair MJ et al. KEYNOTE-189: Updated OS and progression after the next line of therapy (PFS2) with pembrolizumab (pembro) plus chemo with pemetrexed and platinum vs placebo plus chemo for metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(15_suppl):abstr 9013.

Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288–301. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1716948.

Cappuzzo F, Mekhail T, Zer A, Reinmuth N, Sadiq A, Archer V et al. IMpower130: Progression-free survival (PFS) and safety analysis from a randomised phase III study of carboplatin + nab-paclitaxel (CnP) with or without atezolizumab (atezo) as first-line (1L) therapy in advanced non-squamous NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl_8):abstr LBA53. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy424.065.

Papadimitrakopoulou V, Cobo M, Bordoni R, Dubray-Longeras P, Szalai Z, Ursol G et al. IMpower132: PFS and Safety Results with 1L Atezolizumab + Carboplatin/Cisplatin + Pemetrexed in Stage IV Non-Squamous NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(10):S332 (abstr OA05.07). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.08.262.

Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1919–29. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709937.

Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Overall survival with durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(24):2342–50. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1809697.

McMillan SS, King M, Tully MP. How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(3):655–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0257-x.

Niki M, Nakaya A, Kurata T, Yoshioka H, Kaneda T, Kibata K, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor re-challenge in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2018;9(64):32298–30404. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.25949.

Spigel DR, Couture F, Chandler J, Goss G, Keogh G, Garon EB, et al. Randomized results of fixed-duration (1-yr) vs continuous nivolumab in patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl_5):abstract 1297O https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx380.002.

Herbst RS, Monnet I, Novello S, Szalai Z, Gubens MA, Su W-C, et al. Long-term follow-up in the KEYNOTE-010 study of pembrolizumab (pembro) for advanced NSCLC, including in patients (pts) who completed 2 years of pembro and pts who received a second course of pembro. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(suppl_10):abstract LBA4. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy511.003.

Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, Pereira JR, De Marinis F, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1589–97. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163.

Gutiérrez L, Cruz P, Martínez S, Casado G, Vilamayor J, Viñal D. Experiencia clínica con nintedanib en pacientes con cáncer de pulmón no microcítico metastásico. Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica (SEOM). 2018:P 329-E.

Majem M, Juan O, Insa A, Reguart N, Trigo JM, Carcereny E, et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (2018). Clin Transl Oncol. 2019;21(1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-018-1978-1.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Lung cancer: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG122]. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng122. Accessed Mar 2019.

Planchard D, Popat S, Kerr K, Novello S, Smit EF, Faivre-Finn C et al. Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(Supplement_4):iv192–iv237. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy275.

Peters S, Dafni U, Boyer M, De Ruysscher D, Faivre-Finn C, Felip E, et al. Position of a panel of international lung cancer experts on the approval decision for use of durvalumab in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Ann Oncol. 2019;30(2):161–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy553.

Bristol-Myers Squibb. Press Release: bristol-myers squibb provides update on the ongoing regulatory review of opdivo plus low-dose yervoy in first-line lung cancer patients with tumor mutational burden ≥10 mut/Mb. https://news.bms.com/press-release/corporatefinancial-news/bristol-myers-squibb-provides-update-ongoing-regulatory-review. Accessed 19 Oct 2018.

Costantini A, Corny J, Fallet V, Renet S, Friard S, Chouaid C, et al. Efficacy of next treatment received after nivolumab progression in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. ERJ Open Res. 2018;4(2). https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00120-2017.

Gettinger SN, Wurtz A, Goldberg SB, Rimm D, Schalper K, Kaech S, et al. Clinical features and management of acquired resistance to PD-1 axis inhibitors in 26 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(6):831–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2018.03.008.

Grigg C, Reuland BD, Sacher AG, Yeh R, Rizvi NA, Shu CA. Clinical outcomes of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving chemotherapy after immune checkpoint blockade. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):abstr 9082. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9082.

Park SE, Lee SH, Ahn JS, Ahn MJ, Park K, Sun JM. Increased response rates to salvage chemotherapy administered after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(1):106–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2017.10.011.

Schvartsman G, Peng SA, Bis G, Lee JJ, Benveniste MFK, Zhang J, et al. Response rates to single-agent chemotherapy after exposure to immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;112:90–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.07.034.

Corral J, Majem M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Carcereny E, Cortes AA, Llorente M, et al. Efficacy of nintedanib and docetaxel in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma treated with first-line chemotherapy and second-line immunotherapy in the nintedanib NPU program. Clin Transl Oncol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02053-7.

Grohe C, Gleiber W, Haas S, Mueller-Huesmann H, Schulze M, Atz J, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib + docetaxel in lung adenocarcinoma patients (pts) following treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs): First results of the ongoing non-interventional study (NIS) VARGADO. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(Supplement_2):abstract 119O. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz063.017.

Shiono A, Kaira K, Mouri A, Yamaguchi O, Hashimoto K, Uchida T, et al. Improved efficacy of ramucirumab plus docetaxel after nivolumab failure in previously treated non-small cell lung cancer patients. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10(4):775–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.12998.

Bracci L, Schiavoni G, Sistigu A, Belardelli F. Immune-based mechanisms of cytotoxic chemotherapy: implications for the design of novel and rationale-based combined treatments against cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2014;21(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2013.67.

Roselli M, Cereda V, di Bari MG, Formica V, Spila A, Jochems C, et al. Effects of conventional therapeutic interventions on the number and function of regulatory T cells. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(10):e27025. https://doi.org/10.4161/onci.27025.

Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, Powderly JD, Picus J, Sharfman WH, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–75. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609.

Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(5):325–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29.

Lanitis E, Irving M, Coukos G. Targeting the tumor vasculature to enhance T cell activity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;33:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2015.01.011.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the panel experts for their participation in this Delphi study: Ángel Artal (Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Zaragoza); Reyes Bernabé (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla); Carlos Camps (Hospital General Universitario de Valencia); Enric Carcereny (Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona); Manuel Cobo (Hospital Universitario Carlos Haya, Málaga), Pilar Diz (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León), Manuel Dominé (Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz, Madrid), Enriqueta Felip (Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona), Pilar Garrido (Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid), Ignacio Gil Bazo (Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona), José Luis González-Larriba (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), Amelia Insa (Hospital Clínico de Valencia), Óscar Juan (Hospital Universitario Politécnico La Fe, Valencia), Martín Lázaro (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo), Marta López-Brea (Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander), Margarita Majem (Hopital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona), Bartomeu Masuti (Hospital General de Alicante), Teresa Morán (Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona), Ernest Nadal (Hospital Duran i Reynals, Hospitalet), Mariano Provencio (Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), Noemí Reguart (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona), Josefa Terrasa (Hospital de Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca), Nuria Viñolas (Hospital Clínic de Barcelona), Jesús Corral (Clinica Universidad de Navarra, Madrid), Natividad Martínez (Hospital General de Alicante), David Vicente (Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, Sevilla). We would like to thank Carmen González and Andreu Covas (GOT IT, Barcelona, Spain) for facilitating this Delphi project and Aurora O’Brate for providing copyediting editorial support.

Funding

The project was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. The opinions expressed are those of the authors. The funding party did not influence any aspect of the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors would like to disclose the following: Dolores Isla: personal financial interests: consulting and advisory services: Roche, MSD, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Abbvie, Guardant Health, Novartis, Lilly, Astra-Zeneca, Jansen, Sysmex, Blueprint Medicines, Takeda. Speaking, public presentations: Roche, MSD, BMS, Pfizer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Rovi. Institutional financial interests: financial support for clinical trials: Roche, MSD, BMS, Takeda, Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, Pharmamar, Celgene, Sanofi, GSK, Theradex Oncology, BluePrint Medicines. Financial support for contracted research: Guardant Health, Sysmex. Javier de Castro: educational grants: Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Roche. Scientific consulting: Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda. Rosario García Campelo: consulting, advisory role or speaker’s bureau: Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Astra-Zeneca, Roche, MSD. Pilar Garrido: personal financial interests: consulting and advisory services: Roche, MSD, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Abbvie, Guardant Health, Novartis, Lilly, Astra-Zeneca, Jansen, Sysmex, Blueprint Medicines, Takeda. Speaking, public presentations: Roche, MSD, BMS, Pfizer, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Rovi. Institutional financial interests: financial support for clinical trials: Roche, MSD, BMS, Takeda, Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, Pharmamar, Celgene, Sanofi, GSK, Theradex Oncology, BluePrint Medicines. Financial support for contracted research: Guardant Health, Sysmex. Enriqueta Felip: Consulting, advisory role or speaker’s bureau: Abbvie, Astra-Zeneca, Blue Print Medicines, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Eli Lilly, Guardant Health, Janssen, Medscape, Merck KGaA, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, Touchtime. Luis Paz-Ares: Consulting, advisory role or speaker’s bureau: Lilly, MSD, BMS, Roche, Pharmamar, Merck KGaA, Astra-Zeneca, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Servier, Sysmex, Amgen, Incyte, Pfizer, Ipsen, Adacap, Sanofi, Bayer, Blueprint Board Member: Genómica. Research grants to institution: MSD, BMS, Astra-Zeneca, Pfizer. José Manuel Trigo: consulting, advisory role or speaker’s bureau: Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, MSD, Takeda. All remaining authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study consisted of a survey of expert opinions and no patient data were collected, so no specific independent ethical or research review or approval was necessary.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Isla, D., de Castro, J., García-Campelo, R. et al. Treatment options beyond immunotherapy in patients with wild-type lung adenocarcinoma: a Delphi consensus. Clin Transl Oncol 22, 759–771 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02191-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-019-02191-y