Abstract

We have published extensively on the neurogenetics of brain reward systems with reference to the genes related to dopaminergic function in particular. In 1996, we coined “Reward Deficiency Syndrome” (RDS), to portray behaviors found to have gene-based association with hypodopaminergic function. RDS as a useful concept has been embraced in many subsequent studies, to increase our understanding of Substance Use Disorder (SUD), addictions, and other obsessive, compulsive, and impulsive behaviors. Interestingly, albeit others, in one published study, we were able to describe lifetime RDS behaviors in a recovering addict (17 years sober) blindly by assessing resultant Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS™) data only. We hypothesize that genetic testing at an early age may be an effective preventive strategy to reduce or eliminate pathological substance and behavioral seeking activity. Here, we consider a select number of genes, their polymorphisms, and associated risks for RDS whereby, utilizing GWAS, there is evidence for convergence to reward candidate genes. The evidence presented serves as a plausible brain-print providing relevant genetic information that will reinforce targeted therapies, to improve recovery and prevent relapse on an individualized basis. The primary driver of RDS is a hypodopaminergic trait (genes) as well as epigenetic states (methylation and deacetylation on chromatin structure). We now have entered a new era in addiction medicine that embraces the neuroscience of addiction and RDS as a pathological condition in brain reward circuitry that calls for appropriate evidence-based therapy and early genetic diagnosis and that requires further intensive investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Role of Dopaminergic Genetics in Reward Dependence

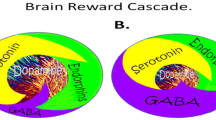

Neurotransmitter interactions regulate brain reward circuitry that result in the release of dopamine (DA) in the major loci for feelings of well-being and reward, the nucleus accumbens (NAc) part of the mesolimbic system of the brain. The inter-relationship of at least four important neurochemical pathways: serotonergic, endorphinergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic constitute the “brain reward cascade” (see Fig. 1) a natural sequence of events that produce feelings of well being. These activities including: the synthesis, vesicle storage, metabolism, release, and function of neurochemicals [1] are regulated by genes, and their expression, in terms of messenger RNA-directed proteins. Thus, genetic testing is a potential window that can be used to identify the specific neurochemistry of individuals and formulate the best treatment options for them [1–13].

Brain Reward Cascade [14, 15]. In this cascade, stimulation of the serotonergic system in the hypothalamus leads to the stimulation of delta/mu receptors by serotonin to cause a release of enkephalin. Activation of the enkephalinergic system induces an inhibition of GABA transmission at the substania nigra by enkephalin stimulation of mu receptors at GABA neurons. This inhibitory effect allows for the fine-tuning of GABA activity. This provides the normal release of dopamine at the projected area of the NAc [14, 15]

DA is a neurotransmitter with multiple important functions including behavioral effects such as “pleasure” and “stress reduction.” Simply stated, without the normal function of this substance, an individual will suffer from cravings and have an inability to cope with stress. Thus, genetic hypodopaminergic brain function predisposes individuals to seek substances and or behaviors that can be used to overcome this craving state by activating the mesolimbic dopaminergic centers [4, 13]. Psychoactive substances like alcohol, psychostimulants and opiates, and risky behaviors like gambling, overeating and thrill seeking [16] induce the release of neuronal DA into the synapse at the NAc, to overcome the hypodopaminergic state of that individual. Temporary relief from the discomfort and a pseudo sense of well-being is the product of this self-medication [17]. Unfortunately, chronic abuse of psychoactive substances leads to inactivation, or a downregulation, like for example, inhibition of neurotransmitter synthesis, neurotransmitter depletion, formation of toxic pseudo neurotransmitters, and through structural receptor dysfunction. Therefore, substance-seeking and pathological behaviors are both used as a means of providing a feel-good response (a “fix”) to lessen uncontrollable cravings. Individuals who possess reward gene polymorphisms or variations, will, given environmental insult be at risk for impulsive, compulsive, and addictive behaviors. Reward Deficiency Syndrome (RDS) is a term used to embrace and characterize these genetically induced behaviors. Any and all of these pathological behaviors, as well as psychoactive drug-abuse, are candidates for addiction including tolerance and dependence. The behavior or drug of choice by the individual is a function of both genes and environmental factors like availability and peer pressure.

Brain Reward Cascade Explanation

DA is crucial to the maintenance of natural rewards while the release of DA into NAc synaptic sites is a somewhat complex cascade of reactive activity that involves neurotransmitters and structures in the limbic system [1]. Blum and Kozlowski first proposed the concept of a “brain reward cascade” in 1990 as a cascade of interactive events and mesolimbic function that produces the net release of DA [1] (see Fig. 1). Simply, the interaction of activities in the separate subsystems of the brain’s reward circuitry combine into the much larger global system, and reveal the cascade of neurotransmission, which merges simultaneously and in a specific sequence. When these systems work normally, they result in a feeling of pleasure, well-being, and peace; an imbalance, or deficiency, on the other hand, will cause the system to function abnormally, displacing the sense of well-being with negative feelings like anxiety, anger, and low self-esteem. The need to mask these negative feelings leads to the use of substances such as alcohol and narcotics, meaning that excessive desires are spurred by the need for DA.

The DA pathway arises in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and culminates in the DA D2 receptors on neurons located in the cell membranes of in the hippocampus and the NAc. Blum and Kozlowski [1] describe a process that begins in the hypothalamus, where the excitatory activities of 5-HT-releasing-neurons cause the release of met-enkephalin, an opioid peptide. The opioid peptide regulates the activity of neurons responsible for the release of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) the inhibitory neurotransmitter at the substantia nigra. When DA-containing neurons in the VTA, and in certain parts of the hippocampus via the amygdala, are disinhibited, DA is allowed to be released into the NAc, permitting the completion of the cascade. If the cascade is functioning correctly, the reward sensation, or the feeling of well-being, is experienced, provided certain basic genetic conditions are fulfilled (see Fig. 1) [1]. However, when the genes that govern the function of the brain reward cascade have polymorphic variations, these risk alleles provide the basis for therapeutic targets.

RDS and Genetic Antecedents

The development of a blueprint for identifying certain candidate genes and polymorphisms that could negatively impact DA release is based on this understanding of the brain reward cascade [2]. Many genes are involved, and it has been adequately established in association studies and animal research literature that, for example, polymorphisms of the serotonergic-2 A receptor (5-HTT2a), DA D2 receptor (DRD2), and the catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT) genes (see Genetic Addiction Risk Score (GARS) test), predispose individuals to aberrant RDS behaviors. These behaviors include craving not only for drugs and alcohol but eating and other addictive behaviors such as pathological gambling (see Table 1) [3]. Gene polymorphisms of both 5-HT and DA can result in significantly lower than normal receptor densities. A COMT gene polymorphism can result in increased catabolism of synaptic DA and subsequent reduction of DA function. These are three examples of how the identification of polymorphisms on these three genes can provide a window into an impaired brain reward cascade, and the identification of individuals at high risk can be accomplished. Based on a published [11] mathematical Bayesian approach, it was found that individuals who carry the Taq A1 polymorphisms of the DRD2 have a 74.4 % chance of developing RDS behaviors, given an environmental insult and epigenetic effects (see Table 1).

Genomics: Evidence-Based Studies

In general, inconsistencies in the literature involving association studies using single gene analysis prompted Conner [4] and others to evaluate a number of dopaminergic gene polymorphisms as predictors of drug use in adolescents. We cannot ignore the importance of neurochemical mechanisms involved in drug-induced relapse behavior, as suggested by Bossert et al. [5] for understanding the interaction of multiple genes and environmental elements. Using a drug relapse model previously shown to induce relapse by re-exposing rats to heroin-associated contexts, these investigators found that after extinction of drug-reinforced responding in different contexts, re-exposure reinstated heroin seeking. This effect was diminished by inhibition of GABA transmission in the VTA and medial accumbens shell and components of the mesolimbic DA system; this process enhances net DA release into the NAc. Indeed, this fits well with Li’s Knowledgebase for Addiction-Related Genes (KARG) addiction network map [6] (see Fig. 2). Li et al. [6] also stressed the view that drug addiction is a serious problem worldwide with strong genetic and environmental influences. And that a variety of technologies were used to discover genes and pathways that underlie addiction however, each individual technology can be biased and incomplete. Li and his colleagues integrated evidence from peer-reviewed publications 2,343 items between 1976 and 2006 that inked genes and chromosomal regions to addiction by single-gene strategies, microarray, proteomics, or genetic studies. They identified 1,500 human addiction-related genes and developed the first molecular KARG (http://karg.cbi.pku.edu.cn), with a friendly web interface and extensive annotations. Their meta-analysis of 396 genes, each supported by two or more independent items of evidence, leads to the identification of 18 molecular pathways that were statistically significant and covered both upstream signaling events and downstream effects. For four different types of addictive drugs and five significant molecular pathways including two new ones; GnRH signaling pathway and gap junction were identified as common pathways that may underlie shared rewarding and addictive actions. In a hypothetical common molecular network for addiction, they connected the common pathways which linked all of these genes, to both the glutaminergic and dopaminergic pathways.

KARG an addiction network map [6]

Following the initial finding of Blum et al. in 1990 [7] showing a positive association of the single gene DRD2 polymorphism in chromosome 11 and severe alcoholism, replication, although favorable has, to date, been fraught with inconsistent results. This has also been true for other complex behaviors [9] when gene-gene and gene-environment interactions are tested the idea that complex gene-relationships may account for inconsistent findings across many different single gene studies is supported [8]. The reasons for inconsistencies in trying to predict drug use are many and varied: they include single gene analysis, poorly screened controls, stratification of population, personality traits, co-morbidity of psychiatric disorders, gender-base differences, positive and negative life events, and neurocognitive dysfunctioning and epigenetic effects [6, 7].

In order to gain a more complex but stronger predictive set of genetic antecedents rather than continue to evaluate single gene associations, we embarked on a study to evaluate multiple candidate genes, especially those linked to the Brain Reward Cascade to predict future drug abuse [1] and identify risk for hypodopaminergic functioning. Although exploratory, the goal is to develop an informative panel based on numerous known risk alleles to provide treatment facilities a means of stratifying patients entering treatment as having a high, moderate, or low, genetic risk prediction.

As noted above, an association between dopaminergic gene polymorphisms and addictive, compulsive, and impulsive behaviors classified as RDS has been revealed in numerous studies. We evaluated subjects derived from two families for a potential association with polymorphisms of the DA D2 receptor gene (DRD2), DA D1 receptor gene (DRD1), DA transporter gene (DAT1), and DA beta-hydroxylase gene (DBH). This association if found would demonstrate the relevance of a generalized RDS behavior set, as the phenotype.

An experimental group derived from up to five generations of two independent multiple-affected families n = 55 were genotyped and compared to very rigorously screened controls. In addition to these subjects, data related to RDS behaviors was collected from 13 deceased family members. The genotyped family members carried the DRD2 Taq1 allele at 78 % the DAT1 10/10 allele at 58 %, the DBHB1 allele at 66 %, and the DRD1 A1/A1 or the A2/A2 genotypes at 35 %. Interestingly, all probands (n = 32) from Family A genotyped for the DRD2 gene carried the TaqA1 allele (100 %). The experimental positive rate for the DRD2 Taq1 allele with an odds ratio of 103.9 (12.8, 843.2) was significantly greater (X 2 = 43.6, P < 0.001). The experimental positive rate for the DAT1 10/10 allele with an odds ratio of 2.3 (1.2, 4.6) was also significantly greater (X 2 = 6.0, P < 0.015). Between the experimental and control positive rates of the DBH, DRD1 A1/A1, or A2/A2 genotypes no significant differences were observed [18].

Patients genetic risk for drug-seeking behavior needs to be evaluated prior to, or upon entry to chemical dependency programs. The importance of genotyping to establish genetic severity for patients undergoing treatment and in danger of relapse is described below in the, as yet, unpublished results from a study of the data from Comprehensive Analysis of Reported Drugs (CARD). We have followed up by evaluating a panel of genes and associated polymorphisms termed GARS in patients with RDS behaviors attending two treatment centers. In this and other studies, we use the GARS for purposes of study identification and commercial testing [9–11].

To determine risk severity of 72 addicted patients, the percentage of prevalence of selected risk alleles was calculated to provide a severity score. We genotyped the patients using a nine reward genes and their polymorphisms (F = 18 alleles; M = 17 alleles). This panel included: DRD 2, 3, 4; MOA-A; COMT; DAT1; 5HTTLLR; OPRM1; and GABRA3 genes. The three severity ratings were: Low severity = 1–36 %; moderate severity = 37–50 %, and high severity = 51–100 %. We studied two distinct treatment populations: Group 1 consisted of 37 addicts from a holistic addiction treatment center in North Miami Beach, Florida, and Group 2 consisted of 35 addicts from Malibu Beach Recovery Center [12]. We are in the process of analyzing 393 subjects using a multi-centered approach across the USA.

However, in the following unpublished experiment, we found risk stratification of the 72 genotyped patients to be as follows: 27 % low risk; 74 % moderate risk, and 4 % severe risk. We are exploring potential risk correlation with the Addiction Severity Index (ASI). Preliminary statistical analysis reveals that with N = 277, we found a significant trend whereby allelic risk above the means score associated with the ASI Alcohol Risk Severity Score at P < 0.07 (one sided P). Unlike CARD, the GARS could provide potential correlations to ASI to at least the alcohol risk composite score. If this finding is upheld through larger populations, it unequivocally demonstrates that objective genetic polymorphisms could predict clinical outcomes.

We are cognizant that, as the next steps in identifying candidate gene polymorphic associations with RDS as the overall phenotype, we must carefully dissect epigenetic effects such as miRNA and subsequent methylation and/or deacetylation of attached chromatin markers leading to altered gene expression in spite of DNA polymorphisms.

CARD™ Provides a Rationale for Genetic Testing

The primary reason to include some brief information regarding CARD is to provide a clear indication that genetic testing may provide valuable information about the risk that drives relapse. In an unpublished study but submitted article from our laboratory, a statistical analysis of unidentifiable data from a computer-based program called CARD was used to evaluate treatment adherence in a large clinical cohort from across a number of eastern states in America. This study consisted of 5,703 patients and 11,403 specimens, in various treatment settings across six eastern states. We found significant levels of both non-compliance and lack of abstinence (risk for relapse) during treatment. The CARD engine addresses issues of metabolism as well as contaminants in the production processes of some formulations. It addresses multi-faceted scenarios within and across drug classes, often involving the state of multiple analytes in order to reach a conclusion for each self-reported or prescribed drug. It evaluates thousands of rule sets to determine if the statement associated with each rule set is applicable to the specimen test results and reported drugs that are analyzed.

We are proposing a paradigm shift on the basis of these studies, whereby the predisposition to a risk for RDS (the true phenotype) can be accurately determined by utilizing GARS, and treatment outcome can be assessed by utilizing CARD. These results confirm the putative role of dopaminergic polymorphisms in RDS behaviors.

The Addiction Phenotype and the Need for Super Controls

The family-based study [18] demonstrates the importance of a nonspecific RDS phenotype and informed an understanding of how evaluating single subset of RDS behaviors, like for example, Tourette’s may lead to spurious results. Rather, the adoption of a nonspecific reward phenotype may be useful in future association and linkage studies involving neurotransmitter gene candidates as utilized in GARS. The putative role of dopaminergic polymorphisms in RDS behaviors is supported by the results [18], although linkage analysis is necessary and the sample size was limited. We believe that using a nonspecific reward phenotype in future association and linkage studies that involve dopaminergic polymorphisms and other neurotransmitter gene candidates may be a necessary paradigm shift.

This underscores the problem concerning appropriate controls. While thousands of studies have associated the various reward gene risk polymorphisms for all types of addictive behaviors (including drugs, smoking, alcohol, gambling, sex, shopping) against putative controls, there remains a real need to develop super controls whereby the true phenotype is not just drug addiction per se but the absence of any RDS behavior. To suggest that researchers can provide accurate data by enlisting comparison individuals who are from an unscreened general population as controls, is fraught with an inappropriate and potentially inaccurate assessment. In one, example, assessing the DRD2 A1 allele, we found that while screened controls (eliminating drug and alcohol abuse) in over 3,000 subjects showed a prevalence of approximately 26 %; when we eliminated all RDS behaviors in the probands and family surprisingly we found the DRD2 A1 allele prevalence to be only 3 % [19]. In the current GARS test being cognizant of this issue, we utilize the recognized method of counting risk alleles to provide addiction risk. Below, we provide a chart showing the remarkable Pub Med (3-16-14) list of articles published on each independent gene involving risk polymorphisms in RDS behavior and controls (Fig. 3).

This is a list of Pub Med articles that associate polymorphisms of reward genes with risk of RDS behaviors. For each gene, there are many polymorphisms, and there are multiple receptors for each listed transmitter. The DRD2 gene is the most widely studied as a single receptor type. Reward Gene Publications 3/16/2014

Theoretical Implications: Substance Abuse and Pain Medications

Understanding that there is a thread between opioid prescribed compounds for pain and addiction liability especially in subjects genetically predisposed to RDS risk provides the rationale to address this growing epidemic globally. The GARS test modified for pain clinics provides an analysis of about 14 genes and associated risk alleles. Thousands of studies in peer reviewed scientific journals have revealed significant associations between certain reward genes, with reward circuitry imbalances in the brain and risk for high substance seeking behavior. The predictive value for just one gene such as the DA D2 receptor gene is as high as 74.4 % as described by Blum et al. [12]. Simply, the occurrence or absence of these single nucleotide polymorphisms may determine a patient’s predisposition to potential treatment outcome and relapse. In addition to addiction risk, it may help guide the physician in determining the use of chronic opioid therapy, and a rationale for continuing urine monitoring consistent with the American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine (ACOEM) guidelines. Most importantly, ACOEM suggests that genetics are an important factor in pain management, and according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), as well as the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), genes are responsible for a 60 % contribution toward addictive behaviors. Not surprisingly, according to the American Pain Society, a physician’s ability to predict an opioid abuser is no better than chance (50 %). In fact, Bornstein’s group [20] found that when clinicians’ only urine test patients suspected of medication misuse, they are missing a significant group; up to 72 % and are quick to make wrong judgments. The ACOEM guidelines on Chronic Opioid Therapy suggest “screening for risk of addiction should be performed before starting a long-term opioid treatment in patients with chronic pain”, thus providing the physician with clues about the necessity for increased attention in susceptible patients. If opioid treatment results in pain control, better functioning, and improved health-related quality of life, the treatment should be continued, even in patients susceptible for addiction. However, these patients will need special attention with a focus on compliance, abstinence from other drugs of abuse and with discussion of the potential consequences of chronic treatment of pain with opioids.

Although the principal pain pathways ascend to the brain from the dorsal horn of the spinal cord the control of sensitivity to pain may reside in the mesolimbic system of the brain at the reward center, where gene polymorphisms may impact pain tolerance and/or sensitivity. These polymorphisms may associate with a predisposition to pain intolerance or tolerance to pain. It is hypothesized that the identification of certain gene polymorphisms may provide a unique therapeutic target to assist in pain treatment. Thus, testing for certain candidate genes like the mu receptors and PENK could assist in the design of pharmacogenomic solutions personalized to each patient and guided by their unique genetic makeup [10], with potential for improvement in clinical outcomes [11].

Understanding the role of neurogenetics in pain relief, including pharmacogenomics and nutrigenomic aspects, will pave the way to better treatment for the millions suffering from both acute and chronic pain. We now know that dopaminergic tone is involved in pain sensitivity mechanisms and even buprenorphine outcome response. The identification of certain gene polymorphisms as unique, therapeutic targets may assist in the treatment of pain. Pharmacogenetic testing for certain candidate genes, like mu receptors and PENK, is proposed, as a means to improve clinical outcomes by the provision of treatment. The use of GARS, as described above, to identify clients with high addiction risk by providing valuable information about genetic predisposition to opioid addiction, could become an important frontline approach, on admission to pain clinics.

One notable study evaluated the role of both mu-opioid receptors (MORs) and delta-opioid receptors (DORs) two genes expressed in the VTA that may be involved in the addictive properties of opiates. Researchers David et al. [21] found that intra-VTA morphine self-administration was abolished in knockout MOR gene mice at all doses tested. While male and female WT and DOR−/− mice exhibited self-administration similarly, however, this behavior was disrupted without triggering physical signs of withdrawal by the administration of Naloxone (4 mg/kg) to WT and DOR mutants. An increase in fos was associated with Morphine ICSA within the NAc, striatum, limbic cortices, amygdala, hippocampus, lateral mammillary nucleus, and the ventral posteromedial thalamus where high levels of fos were expressed exclusively in self-administering WT and DOR−/− mice. Abolition of morphine reward in MOR−/− mice was associated with a decrease in fos positive neurons in the mesocorticolimbic DA system, amygdala, hippocampus (CA1), lateral mammillary nucleus, and a complete absence within the ventral posteromedial thalamus. David et al. [21] concluded that (a) ventral posteromedial thalamus MORs, but not DORs, are critical for morphine reward and (b) the role of VTA-thalamic projections in opiate reward warrants further exploration.

Moreover, clinical and laboratory studies have indicated that the MOR gene contributes to inheritable vulnerability to the development of opiate addiction. Polymorphisms that occur naturally have been identified in the MOR gene. Substitutions occur at high allelic frequencies (10.5 and 6.6 %) in two coding regions single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the A118G and C17T respectively, of the MOR gene. These SNPs cause amino acid changes in the receptor that impact on an individual’s response to opioids and can influence increases or decreases in vulnerability to opiate addiction [22]. Thus, in response to beta-endorphin in cellular assays, the A118G substitution encodes a variant receptor with differences in binding and signal transduction [22]. Finally, to firmly establish the role of MOR in reward and response to buprenorphine, Ide et al. [23] assessed buprenorphine anti-nociception by hot-plate and tail-flick tests, and found that it was significantly reduced in heterozygous mu-opioid receptor knockout (MOR-KO) mice and abolished in homozygous MOR-KO mice. Buprenorphine, on the other hand, was able to establish a conditioned place preference in homozygous MOR-KO, although as the number of copies of wild-type mu-opioid receptor genes was reduced, the magnitude of place preference was reduced. This study revealed that mu-opioid receptors mediate most of analgesic properties of buprenorphine [23]. We are proposing that to determine patient addiction liability, genetic testing should be incorporated into the beginning of Occupational Medical Clinic programs to reduce iatrogenic opioid prescription addiction, and should include both opioid and dopaminergic risk alleles.

Explanation of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms

RDS-associated SNPs can be identified by any suitable method, including DNA sequencing of patients diagnosed with one or more RDS behaviors. After validation, newly identified RDS-associated SNPs can be used in the test. As will be appreciated, once identified and validated, the presence, if any, of one or more RDS-associated SNPs in the nucleic acids derived from a biological sample taken from a patient can be determined using any suitable now known or later-developed assay, including those that rely on site-specific hybridization, restriction enzyme analysis, or DNA sequencing. Table 2 lists a number of particularly preferred RDS-associated SNPs, whereby, the detection of which can be used for the GARS test.

Serotonin (5-Hydroxytriptamine5-HT) Genes (2AReceptor1438G/a)

Serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT, is a neurotransmitter and peripheral NH2 signal mediator that was discovered in the late 1940s. By the early 1950s, neurotransmitter function was identified in the central nervous system of animals. In the late 1950s, there was evidence for 5-HT receptor peripheral heterogeneity, and by 1979, 5-HT binding sites were identified in the brain: 5-HT1 and 5-HT2. 5-HT 2A receptor (5-HT2A) is one of several proteins to which 5-HT binds when brain cells communicate. 5-HT receptors located on the membranes of nerve and other cell types mediate the effects of 5-HT as the endogenous ligand. 5-HT receptors are heptahelical; G protein coupled seven trans-membrane receptors, activated by an intracellular second messenger cascade except for the 5-HT3 receptor, a ligand gated ion channel. The 5-HT receptor contains 471 amino acids in rats, mice, and humans and is widely distributed in peripheral and central tissues. 5-HT receptors mediate contractile responses in a series of vascular smooth muscle preparations. In addition, platelet aggregation and increased capillary permeability following exposure to 5-HT have been linked to 5-HT receptor-mediated functions. Centrally, these receptors are located principally on cells in the cerebral cortex, claustrum, and basal ganglia. 5-HT receptors reduce cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and modify the activity and release of other neurotransmitters like glutamate, enkephalin, DA, and GABA. 5-HT2A receptors increase glutamate activity of in many areas of the brain, some of the other 5-HT receptors have the effect of suppressing glutamate. The therapeutic actions that result from increased stimulation of 5-HT receptors in anti-depressant and anxiolytic treatments seems to be opposed by increased stimulation of the 5-HT2A receptors.

Serotonin Receptors (2A) Genetics

Everyone inherits two copies of the 5-HT2A receptor gene, one from each parent. Small differences in the chemical sequence results, in some people having an adenine (A), switched at the same point for a guanine (G). So a subject can have gene types AA, AG, or GG. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, “whether depressed patients will respond to an antidepressant depends in part, on which version of a gene they inherit.” The chance of a positive response to an antidepressant increase by up to 18 % in those who have two copies of one version of a gene that codes for a component of brain mood-regulation. It is well known that polymorphisms at the 5-HT2A receptor gene vary in terms of frequency, for example, Whites have six times more of the minor allelic version compared to Blacks. These and other findings add to evidence that the component is a receptor for chemical antidepressant action. Serotonergic genes have been also associated with suicide ideation, trauma in children, and criminality [24, 25].

Specifically related to chemical dependencies, these particular genes have been associated with heroin dependence. The 5-HT2A-1438A allele was significantly more common in heroin dependent patients than controls [0.55 and 0.45, respectively; corrected P = 0.042]. An interaction between A-1438G of 5-HT2A and 5-HTT polymorphisms was observed, in the presence of short 5-HTTLPR alleles and 12-repeat 5-HTT VNTR the association between heroin dependence and the −1438AA vs. AG/GG genotypes was enhanced [24.8 % in heroin-dependent patients vs. 12.6 % in controls; corrected P = 0.045] [26]. Moreover, genetic analyses showed that the frequency of 102C allele and C102C genotype in alcoholic subjects was significantly higher than in controls. In addition, alcoholic patients homozygous for C allele had alcoholic problems at significantly earlier age of onset than subjects having at least one T allele. These results point to the possibility of a role for the T102C HTR2A polymorphism in development of alcohol dependence and even relapse [27, 28]. Additionally, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C receptors that innervate the DA meso-accumbens pathway may play a prominent role in the behavioral effects of cocaine [29]. Smoking behavior is influenced by genetic factors affecting the dopaminergic system, and dopaminergic polymorphisms have been linked to smoking habits [30]. Since this T102C polymorphism of the 5-HT2A receptor gene modulates the mesolimbic DA system and is associated with reduced receptor gene expression, the purpose of one study [31] was to investigate the relationship it has to tobacco use. The T102C polymorphism was found to be associated with maintenance, but not with the initiation of the smoking habit. The CC genotype was more frequent in current smokers than in never- or former-smokers (chi2 = 6.825, P = 0.03) with an odds ratio of 1.63, 95 % CI 1.06–2.51. Interestingly, Nichols et al. [32] found that the gene response to LSD was quite dynamic. The expression of some genes increased rapidly and decreased rapidly while other genes changed more gradually. Dose-response studies showed two classes: (1) gene expression maximally stimulated at lower doses, and (2) gene expression that continued to rise at the higher doses. In a series of experiments that used receptor specific antagonists, the role of the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in mediating the increases in gene expression, was examined and found that the 5-HT2A receptor activation was responsible for the majority of expression increases.

5-HTTLPR (Serotonin Transporter-Linked Polymorphic Region)

The human 5-HT transporter is encoded by the SLC6A4 gene on chromosome 17q11.1-q12. This is the site for cellular reuptake of 5-HT and a site where many drugs with central nervous system effects are activated. They include therapeutic agents like antidepressants and psychoactive drugs of abuse like cocaine. The 5-HT transporter has a prominent role in the metabolic cycle of many antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, anti-emetics, and anti-migraine drugs. Higher expression of brain 5-HTT is associated with the (long allele) insertion variant compared to the (short allele) deletion variant. The results of some studies show that long allele is responsible for increased 5HT transporter mRNA transcription in human cell lines. Further, this may be due to the A-allele of rs25531, so that subjects with the long-rs25531 (A) allelic combination (LA) have higher levels, with the long-rs25531(G) earners have levels more similar to short-allele carriers. Saiz et al. [26] found an excess of -1438G and 5-HTTLPR L carriers in alcoholic patients in comparison to the heroin dependent group, the polymorphisms A-1438G and 5-HTTLPR also distinguished, alcohol from heroin dependent patients. The association of -1438A/G was especially pronounced with alcohol dependence when 5-HTTLPR S/S was present, less evident with 5-HTTLPR L/S, and not present with 5-HTTLPR.

The 5-HT transporter, encoded by the SLC6A4 gene, influences the synaptic actions of 5-HT and is responsive to stress hormones. In fact, the risk for suicidal behavior in CT exposed individuals is independently affected by the 5′ and 3′SLC6A4 functional variants [25]. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health data shows that there is a significant gene-environment correlation between 5-HTTLPR and neglect for females only. Findings also reveal that 5-HTTLPR is associated with an increased risk of neglect for females and neglected females’ risk of abusing marijuana [33]. Socialization scores were significantly lower in males (greater sociopathy), with the L′L′ genotype (i.e., those homozygous for the L (A) allele) than males who carried the S′ allele (P = 0.03). In contrast, women with the S′S′ genotype tended to have a lower Socialization Index on the California Psychological Inventory than women with one copy of the L′ allele (P = 0.07) and lower socialization scores than women with two L′ alleles (P = 0.002). The tri-allelic 5-HTTLPR polymorphism had opposite effects on socialization scores in men than women with alcohol use disorders [34].

The genotype coding for low 5-HTT expression is associated with a better opioid analgesic effect, while the 5-HTTLPR s-allele has been associated with higher risk of developing chronic pain conditions. Downregulation of 5-HT1 receptors has been associated with the s-allele, and Kosek et al. [35] have suggested that individuals have an increased analgesic response to opioids during acute pain stimuli with a desensitization of 5-HT1 receptors, but may still be at increased risk of developing chronic pain conditions. The risk of alcohol dependence and co-occurring clinical features is increased in the presence of the short (S) allele of the 5-HT transporter gene promoter polymorphism (5-HTTLPR). While no other factor that were measured played a significant role, the S allele was significantly associated with relapse (P = 0.008). Thus, in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients the risk of relapse may be influenced by S allele of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, possibly through intermediate phenotypes [36].

Catecholamine-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met Polymorphism

Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) was discovered in 1957 by the Nobel Prize Winner biochemist Julius Axelrod. COMT is an extra cellular enzyme that breaks down DA, adrenaline, and noradrenaline in the synapse. COMT is involved in the metabolism of the catecholamine neurotransmitters (DA, epinephrine, and norepinephrine). The enzyme introduces a methyl group donated by SA-denosyl-methionine to the catecholamine. Any compound having a catechol structure, like catechol-estrogens and catechol-containing flavonoids, are substrates of COMT, for example, l-dopa, a precursor of catecholamines and an important substrate of COMT. Variability of the COMT activity has previously been associated with the Val158Met polymorphism of the COMT gene and alcoholism. Serý et al. [37] found an association between alcoholism in male subjects and the Val158Met polymorphism of the COMT gene. Serý et al. also found the significant difference between allele and genotype frequencies of male alcoholics and male controls. In one of the subjects genotyped with heroin addiction, carries of the DRD2 A1 allele, also carried the low enzyme COMT activity genotype (A/A). This is in agreement with the work of Cao et al. [38] in 2003 who found no association with the high G/G and heroin addiction. No significant differences in genotype and allele frequencies of 108 val/met polymorphism of COMT gene were observed between heroin-dependent subjects and normal controls. No differences in genotype and allele frequencies of 900 Ins C/Del C polymorphism of COMT gene were observed between heroin-dependent subjects and normal controls. While there is still some controversy regarding the COMT association with heroin addiction, it was also interesting that the A allele of the val/met polymorphisms (−287 A/G) found by Cao et al. [38] was found to be much higher in heroin addicts than controls. Faster metabolism results in reduced DA availability at the synapse, which reduces postsynaptic activation, inducing hypodopaminergic functioning. Generally, Vandenbergh et al. [39] in 1997, and others [40] supported an association with the Val allele and Substance Use Disorder, but others did not [41]. Li et al. [42] found the COMT rs737866 gene variants were independently associated with both novelty seeking (NS) and age of onset of drug use. Those subjects with the TT genotype had higher NS subscale scores and an earlier onset age of heroin use than individuals with CT or CC genotypes. In a multivariate analysis, the inclusion of the NS sub score variable weakened the relationship between the COMT rs737866 TT genotype and an earlier age of onset of drug use. Li’s findings that COMT is associated with both NS personality traits and with the age of onset of heroin use helps to clarify the complex relationship between genetic and psychological factors in the development of substance abuse. Case-control analyses did not show any significant difference in allele or genotype distributions. However, a dimensional approach revealed a significant association between the COMT-Val (158) Met and NS. Both controls and opiate users with Met/Met genotypes showed higher NS scores compared to those with the Val allele. Demetrovics et al. [43] reported the NS scores also were significantly higher among opiate users; however, no interaction was found between group status and COMT genotype. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism (a common normal variant) of the gene for COMT has been shown to affect cognitive tasks broadly related to executive function, such asset shifting, response inhibition, abstract thought, and the acquisition of rule sorting structure. This polymorphism in the COMT gene results in the substitution of the amino acid valine for methionine. It has been shown that this valine variant catabolizes DA at up to four times the rate of its methionine counterpart resulting in a significant reduction of synaptic DA following neurotransmitter release, ultimately reducing dopaminergic stimulation of the post-synaptic neuron [44] another driver in the GARS.

Monoamine Oxidase-A

Monoamine oxidase-A (MAOA) is an enzyme that degrades the neurotransmitters 5-HT, norepinephrine, and DA in the mitochondria. MAOA is involved with both physical and psychological functioning and classified as a flavoprotein since it contains the covalently bonded cofactor FAD. MAOA is an oxidative catalyst that uses oxygen to deaminate-remove an amine group from molecules, resulting in the corresponding aldehyde and ammonia.

Both forms of MOA (A and B) enzymes are substrates for the activity of a number of monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs and are, therefore, well known in pharmacology. They are particularly important in the catabolism of monoamines ingested in food and vital to the inactivation of monoaminergic neurotransmitters. They display different specificities MAO-A primarily breaks down serotonin, melatonin, norepinephrine, and epinephrine while phenylalanine and benzyl amine are mainly broken down by MAO-B. Both forms break down DA, tyramine and tryptamine equally.

The gene that encodes MAOA is found on the X chromosome is located 1.2 kb upstream of the MAOA coding sequences and contains a polymorphism (MAOA-uVNTR) [45]. The MAOA-uVNTR consists of a 30-base pair repeated sequence, six allele variants containing either 2-, 3-, 3.5-, 4-, 5-, or 6-repeat copies [46]. Functional studies have indicated the alleles confer variations in transcriptional efficiency, for example, the 3.5- and 4-repeat alleles result in higher efficiency, whereas, the 3-repeat variant conveys lower efficiency [47]. To date, there are fewer consensuses regarding the transcriptional efficiency of the other less commonly occurring alleles, for example, 2-, 5-, and 6-repeat. The MAOA gene is a highly plausible candidate for effecting differences in the manifestation of psychological traits and psychiatric disorders based on its primary role in regulating monoamine turnover, and thereby influencing levels of norepinephrine, DA, and 5-HT [48]. Levels of MAO-A in the brain of patients with major depressive disorder, measured using positron emission tomography (PET), are elevated by an average of 34 %. Recently, evidence has indicated that the MAOA gene may associate with depression [49] and stress [50]. Evidence regarding whether lower or higher transcriptional efficiency of the MAOA gene, is positively associated with psychological pathology, has however, been mixed. The MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism low-activity 3-repeat allele has been positively related to symptoms of cluster B personality disorders and antisocial personality [51]. Other studies suggest that unhealthy psychological characteristics such as trait aggressiveness and impulsivity are related to alleles associated with higher transcriptional efficiency. Low MAO activity and the neurotransmitter DA are both important factors in the development of alcohol dependence. Huang et al. [52] investigated whether the association between the DRD2 gene and alcoholism is affected by different polymorphisms of the MAO type A (MAOA) gene since MAO is an important enzyme associated with the metabolism of biogenic amines. They found that the genetic variant of the DRD2 gene associated with the anxiety, depression (ANX/DEP) alcoholic phenotype, and the genetic variant of the MAOA gene was associated with alcoholism. Specifically, subjects carrying the MAOA 3-repeat allele and genotype A1/A1 of the DRD2 were 3.48 times more likely to be ANX/DEP alcoholics than the subjects carrying the MAOA 3-repeat allele and DRD2 A2/A2 genotype. Thus, the MAOA gene may modify the association between the DRD2 gene and ANX/DEP alcoholic phenotype. Overall, Vanyukov et al. [53] suggested that, although not definitive, variants in MAOA account for a small portion of the variance of risk for Substance Use Disorder, possibly mediated by liability to early onset behavioral problems.

Dopamine D1 Receptor Gene

The DA receptor D1, also known as DRD1 a subtype of the DA receptor is a protein encoded by the DRD1 gene and the most abundant DA receptor in the human central nervous system where it expresses primarily in the caudate putamen. This G-protein-coupled receptor activates cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinases and stimulates adenylyl cyclase. D1 receptors regulate neuronal growth and development, modulate DA D2 receptor-mediated events and mediate some behavioral responses. There are two transcript variants of the DRD1 gene that are initiated at alternate transcription sites.

The DA D1 receptor has been associated with many brain functions that include, motor control, inattentive symptoms, and reward and reinforcement mechanisms. Betel et al. [54] found that the DRD1 gene polymorphism T allele of the rs686 was significantly (P = 0.0008) more frequent in patients with alcohol dependence. Frequency increased with severe dependence and was even higher for patients with severe complications like withdrawal seizures. Alcohol dependence was significantly, more precisely associated with a specific haplotype rs686*T-rs4532*G within the DRD1 gene. In another study, Kim et al. [55] found that the severity of the alcohol-related problem as measured by the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test in a gene dose-dependent manner, was significantly associated with one 5′ UTR polymorphism in the DRD1 (DRD1-48A>G) gene; 24.37 (±8.19) among patients with −48A/A genotype, 22.37 (±9.49) among those with −48A/G genotype, and 17.38 (±8.28) among those with −48G/G genotype (P = 0.002). Novelty seeking, harm avoidance and persistence were also found to be associated with the DRD1-48A>A genotype. Most recently, Peng et al. [56] indicated that DRD1 gene polymorphism may be associated with the rapid acquisition of heroin dependence, from first drug use but may not play an important role in the susceptibility to heroin dependence in the Chinese Han population. Others have also found significant associations with opiate abuse relative to controls [57]. DRD1 antagonists may indeed reduce the acquisition of cocaine-cue associations and cocaine-seeking behavior. Genetic association studies revealed that polymorphisms of the DRD1 gene significantly associated with nicotine dependence [58]. Ni et al. [59] found a significant association between DRD1 and bipolar disorder for haplotype TDT analysis. Thus, these results suggest DRD1 may play a role in the etiology of bipolar disorder.

Dopamine D2 Receptor Gene (DRD2)

DA receptor D2, also known as DRD2, is a protein that is encoded by the DRD2 gene which encodes the D2 subtype of the DA receptor in humans. This G protein-coupled receptor inhibits adenyl cyclase activity. Two transcript variants encode different isoforms and a third variant that has been described are the result of alternative splicing of the gene. In mice, of D2R surface expression is regulated in the dentate gyrus by the calcium sensor NCS-1 and controls exploration, synaptic plasticity, and memory formation.

DA has the chemical formula (C6H3 (OH)2-CH2-CH2-NH2) is a member of the catecholamine family. DA is a precursor to the chemical messengers’ epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). Arvid Carlsson won a share of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for showing that DA is not just a precursor to these substances, but is also a neurotransmitter.

Older antipsychotic drugs, like haloperidol and chlorpromazine are DRD2 antagonists, however they are exceedingly nonselective, being selective for the “D2-like family” receptors; binding to D2, D3, and D4 and many other receptors, such as, those for 5-HT and histamine. This lack of selectivity makes them difficult to research and results in a range of side effects. Similarly, older DA agonists like bromocriptine and cabergoline used to treat Parkinson’s disease are also poorly selective. However, the number of selective D2 ligands available for scientific research is likely to increase.

Almost a decade before Carlsson and others were awarded the Nobel Prize the DA D2 receptor gene (DRD2) was first associated with severe alcoholism and is today the most widely studied gene in psychiatric genetics [7]. The Taq1 A is a SNP (rs: 1800497) originally thought to be located in the 3′-untranslated region of the DRD2 but has since been shown to be located within exon 8 of an adjacent gene, the ankyrin repeat and kinase domain containing 1 (ANKK1). Importantly, while there may be distinct differences in function, the miss-location of the Taq1A allele may be attributable to the ANKKI and the DRD2 being on the same haplotype or the ANKKI being involved in reward processing through a signal transduction pathway [60]. The ANKKI and the DRD2 gene polymorphisms may have distinct and different actions with regard to brain function [61]. Presence of the A1+ genotype (A1/A1, A1/A2) compared to the A− genotype (A2/A2) is associated with reduced receptor density [62–64]. This reduction causes hypodopaminergic functioning in the DA reward pathway. Other DRD2 polymorphisms such as the C (57T, A SNP (rs: 6277)) at exon 7 also associates with a number of RDS behaviors including drug use [65]. Compared to the T− genotype (C/C), the T+ genotype (T/T, T/C) is associated with reduced translation of DRD2 mRNA and diminished DRD2 mRNA, leading to reduced DRD2 density and a predisposition to alcohol dependence [66]. The Taq1 A allele is a predictive risk allele in families [67].

More recently, Kraschewski and colleagues [68] found the DRD2 haplotypes I-C-G-A2 and I-C-A-A1 to occur with a higher frequency in alcoholics. The rare haplotype I-C-A-A2 occurred less often in alcoholics and was less often transmitted from parents to their affected children (1 vs. 7). Among the subgroups, I-C-G-A2 and I-C-A-A1 had a higher frequency in Cloninger 1 alcoholics and alcoholics with a positive family history. Cloninger 2 alcoholics had a higher frequency of the rare haplotype D-T-A-A2 as compared with controls. In patients with a positive family history, haplotype I-C-A-A2 and Cloninger 1 alcoholics, haplotype I-T-A-A1 was less often present, confirming that haplotypes, which are supposed to induce a low DRD2 expression, were associated with alcohol dependence. Furthermore, supposedly high-expressing haplotypes weakened or neutralized the action of low-expressing haplotypes [68]. Moreover, Kazantseva et al. [69] found, significant effects of the ANKK1/DRD2 Taq1A on “Neuroticism” and of SLC6A3 rs27072 on “Persistence” in both genders. The association between ANKK1/DRD2 Taq1A A2/A2-genotype and higher Novelty Seeking and lower Reward Dependence was shown in men but not in women.

Dopamine D3 Receptor Gene

The DA D3 receptor is a protein that is encoded by the DRD3 gene in humans and is a subtype of the DA receptor which inhibits adenylyl cyclase through inhibitory G-proteins. This receptor is expressed in older regions of the brain phylogenetically. This suggests that it is important in emotional functions. It is a target for drugs that treat Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and drug addiction. Differently encoded isoforms from alternative gene splicing result in transcription of multiple variants. Some of these variants may be subject to nonsense-mediated decay, however, in rodent models of depression D3 agonists like pramipexole, rotigotine, and 7-OH DPAT, among others, display antidepressant effects.

Data from Vengeliene et al. [70] revealed an up-regulation of the DA D3 receptor (D3R) in the striatum after 1 year of voluntary alcohol consumption of alcohol preferring rats that was confirmed by qRT-polymerase chain reaction. This finding was further supported by up-regulation of striatal D3R mRNA found in non-selected Wistar rats, after long-term alcohol consumption when compared with age-matched control animals. Moreover, they examined the role of the D3R in mediating alcohol relapse behavior. They used the alcohol-deprivation-effect model, in long-term alcohol drinking Wistar rats and the model of cue-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior, using the selective D3R antagonist SB-277011-A (0, 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg) and the partial agonist BP 897 (0, 0.1, 1, and 3 mg/kg). Both treatments caused a dose-dependent reduction of relapse-like drinking in the alcohol-deprivation-effect model, as well as a decrease in cue-induced ethanol-seeking behavior. They concluded that long-term alcohol consumption led to an up-regulation of the DA D3R that might have contributed to alcohol-seeking and relapse. Moreover, the Gly9, Gly9 genotype of the DRD3 Ser9Gly polymorphism was associated with increased rates of obsessive personality disorder symptomatology [71].

Furthermore, several lines of evidence indicate that dopaminergic neurotransmission is involved in the regulation of impulsive aggression and violence and that genetically determined variability in dopaminergic gene expression modifies complex traits including that of impulsivity and aggression. In one study, Retz et al. [72] reported an association of the DRD3 polymorphism with impulsiveness according to Eysenck’s EIQ and scores on the German short version of the Wender Utah Rating Scale (WURS-k), which they used for the assessment of a history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms. This association was detected in a group of violent offenders, but not in non-violent individuals. Highest scores of EIQ impulsiveness and the WURS-k were found in heterozygous violent individuals while homozygotes showed significant lower rating scores, suggesting a heterosis effect. The results of their study suggest that variations of the DRD3 gene are likely involved in the regulation of impulsivity and some psychopathological aspects of ADHD related to violent behavior.

Finally, as opiates increase DA transmission, Spangler et al. [73] measured the effects of morphine on DA-related genes using a real-time optic PCR assay that reliably detects small differences in mRNA in discrete brain regions. As reported previously by others, there was no alteration in D1R mRNA and a 25 % decrease in D2R mRNA in the caudate-putamen, 2 h after the final morphine injection. Importantly, in the same RNA extracts, D3R mRNA showed significant increases of 85 % in the caudate-putamen and 165 % in the ventral midbrain, including the substantia nigra and VTA. There were no other significant morphine effects. The understanding of the ability of D3R agonists to reduce the effects of morphine was extended by the finding that chronic intermittent injections of morphine caused an increase in D3R mRNA extends.

Dopamine D4 Receptor Gene

The DA receptor D4 is encoded by the DRD4 gene on chromosome 11 located in 11p15.5 in humans. Like the DRD2 the D4 receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor, activated by the neurotransmitter DA. It also inhibits the adenylate cyclase enzyme which reduces the intracellular second messenger cyclic AMP concentration. The DRD4 has been associated with numerous psychiatric and neurological conditions including addictive behaviors, and eating disorders (like binge-eating anorexia and bulimia nervosa, bipolar disorder) schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. Slight variations (mutations/polymorphisms) in the human DRD4 gene include: A 48-base pair VNTR in exon 3; 13-base pair deletion of bases 235 to 247 in exon 1; C-521T in the promoter; Val194gLY; 12 base pair repeat in exon I; A polymorphic tandem duplication of 120 bp. These mutations have been associated with a number of behavioral phenotypes, including autonomic nervous system dysfunction, ADHD, schizophrenia, and the personality trait of novelty seeking. Specifically, the 48-base pair VNTR in exon 3 ranges from 2 to 11 repeats. Polymorphisms with 6 to 10 repeats are the “Long” versions of the alleles. The frequency of the alleles varies considerably between populations, for example, the incidence of the 7-repeat version is high in America and low in Asia. The DRD4 long variant, or more specifically the 7 repeat (7R), has been loosely linked to psychological traits and disorders like susceptibility for developing ADHD appears to react less strongly to DA molecules. The 7R allele appears to have been selected about 40,000 years ago then in 1999, Chen et al. [74, 75] showed that nomadic populations had higher frequencies of 7R alleles than sedentary ones. They also observed that higher frequency of 7R/long alleles in populations who migrated further from 1,000 to 30,000 years ago. Recently, it was found that Ariaals with the 7R alleles, who are newly sedentary (non-nomadic), are not as healthy as nomadic Ariaal men with 7R alleles [76].

Despite early findings of an association between the DRD4 48 bp VNTR and novelty seeking (characteristic of exploratory and excitable people), a 2008 meta-analysis compared 36 published studies of novelty seeking and the polymorphism and found no effect. The meta-analysis of 11 studies did find that another polymorphism in the gene, the −521C/T, showed an association with novelty seeking [77]. In any case, novelty-seeking behavior probably is mediated by several genes, and the variance attributable to DRD4 by itself is not particularly large.

Several studies have suggested that parenting may affect the cognitive development of children with the 7-repeat allele of DRD4 [78]. Parenting that has maternal sensitivity, mindfulness, and autonomy-support at 15 months was found to alter children’s executive functions at 18 to 20 months [78]. Children with poorer quality parenting were more impulsive and sensation seeking than those with higher quality parenting [78]. Higher quality parenting was associated with better effortful control in 4-year-olds [78] and these effects are impacted by epigenetic markers on chromatin structures.

There is evidence that the length of the D4 DA receptor (DRD4) exon 3 variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) affects DRD4 functioning by modulating the expression and efficiency of maturation of the receptor [79]. The 7R VNTR requires significantly higher amounts of DA to produce a response of the same magnitude as other size VNTRs [80], and this reduced sensitivity or DA resistance leads to hypodopaminergic functioning. Thus, 7R VNTR has been associated with substance-seeking behaviors [81, 82]. However, not all reports support this association. Biederman et al. [83] evaluating a number of putative risk alleles using survival analysis, revealed that by 25 years of age, 76 % of subjects with a DRD4 7R allele were estimated to have significantly more persistent ADHD compared with 66 % of subjects without the risk allele. In contrast, there were no significant associations between the course of ADHD and the DAT1 10-repeat allele and 5HTTLPR long allele. These findings suggested that the DRD4 7R allele, is associated with increased persistence in the course of ADHD. Moreover, Grzywacz et al. [84] evaluated the role of DRD4 exon 3 polymorphisms (48 bp VNTR) in the pathogenesis of alcoholism and found significant differences in the short alleles (2–5 VNTR) frequencies, between controls and patients with a history of delirium tremens and/or alcohol seizures. A trend also was observed in the higher frequency of short alleles amongst individuals with an early age of onset of alcoholism. The results of this study suggest that inherited short variants of DRD4 alleles (3R) may play a role in the pathogenesis of alcohol dependence and carriers of the 4R may have a protective effect for alcoholism risk behaviors. It is of further interest that work from Kotler et al. [85] in heroin addicts illustrated that central dopaminergic pathways figure prominently in drug-mediated reinforcement including novelty seeking, suggesting that DA receptors are likely candidates for association with substance abuse. These researchers showed that the 7R allele was significantly over-represented in the opioid-dependent cohort and conferred a relative risk of 2.46.

Dopamine Transporter Gene (DAT1)

The DA transporter, also known as DA active transporter (DAT, SLC6A3), moves DA the neurotransmitter out of the synapse back into the cytosol via a membrane-spanning protein pump. From there, DA and norepinephrine are sequestered by other transporters into vesicles for later storage and release. DA reuptake through which DA is cleared from synapses primary by the mechanism of the DAT gene, although in the prefrontal cortex, there may be an exception, where evidence points to a larger role for the norepinephrine transporter [86, 87].

DAT is thought to be implicated in a number of DA-related disorders, including ADHD, bipolar disorder, clinical depression, and RDS. The gene that encodes the DAT protein is located on human chromosome 5, consists of 15 coding exons and is roughly 64 kbp long. Evidence for the associations between DAT- and DA-related disorders has come from a type of genetic polymorphism, known as a VNTR, in the DAT gene (DAT1), which influences the amount of protein expressed. DAT is an integral membrane protein that removes DA from the synaptic cleft and deposits it into surrounding cells, thus terminating the signal of the neurotransmitter. DA underlies several aspects of cognition, including reward, and DAT facilitates regulation of that signal [88, 89].

In the model for monoamine transporter function that is most widely accepted, before DA can bind sodium ions must bind to the DAT extracellular domain. Once DA binds to sodium ions change in the conformation of the protein allows both the DA and the sodium to unbind intracellularly [90]. Studies using electrophysiology and radioactive-labeled DA have confirmed that DA is transported across the neuronal membrane with sodium ions. The chlorine ions are required to prevent a buildup of positive charge. These studies have demonstrated that the direction and rate of transport, depends on the sodium gradient [77]. It is known that any resultant activity changes in membrane polarity will profoundly affect transport rates and depolarization will induce DA release [91].

Like the GABA transporter, the brain distribution of DAT is highest in the nigrostriatal, mesocortical, and mesolimbic pathways [92] and gene expression patterns in adult mouse show that expression is high in the substantia nigra pars compacta [93]. It has been confirmed that DAT in the mesocortical pathway was also found in the VTA. DAT is localized in the axon terminals of the striatum and shown experimentally to be co-localized with nigrostriatal terminals, tyrosine, and DA D2 receptors. These results suggest that striatal DA reuptake may occur and DA diffuses into the substantia nigra from the synaptic cleft. It appears that DAT is transported into the dendrites, where it can be found in pre- and postsynaptic active zones, smooth endoplasmic reticulum, and plasma membrane. These localizations suggest that intracellular and extracellular DA levels of nigral dendrites are modulated by DAT.

Genetics and Regulation

The gene for DAT is located on chromosome 5p15, it is confirmed that the protein encoding for the gene is over 64 kb long and comprises 15 coding segments or exons [94]. The DAT gene has a VNTR at the intron 8 region and another at the 3′ end (rs28363170) [95]. VNTR differences have been shown to influence the basal level of expression of the transporter and associate with RDS behaviors, such as various addictions and other DA-related disorders [96]. Interestingly, Nurri, a nuclear receptor that regulates many DA-related genes, can bind the promoter region of this gene and subsequently induce expression [97]. In addition, the DAT promoter also may be the target of the transcription factor Sp-1. Kinases are essential for functional regulation of this protein. The rate at which DAT removes DA from the synapse affecting the quantitative amount of DA in the cell depends upon kinases. Understanding the molecular neurobiology of the DAT gene provides the basis for studies showing hyperactivity, severe cognitive deficits, and motor abnormalities of mice with no DA transporters [98]. Similarities of these effects to the symptoms of ADHD characteristics are striking. Differences in the functional differences, in VNTR, have been identified as risk factors for bipolar disorder [99] and ADHD [100]. Although controversial, data have emerged that suggest there also is an association with stronger alcohol withdrawal symptoms [101, 102]. On the other hand, non-smoking behavior and ease of quitting is associated with an allele of the DAT gene of the with normal protein levels [103]. Additionally, male adolescents in high-risk families, with an absence of maternal affection and a disengaged mother, who carry the 10-allele VNTR repeat, associate with a statistically significant affinity for antisocial peers [104]. Increased DAT activity is associated with clinical depression [105]. Decreased DAT levels of expression are associated with aging, and may underlie a mechanism that compensates for decreases in DA release as a person ages [106].

Cocaine reduces the rate of transport, blocking DAT by binding directly to the transporter [107]. In contrast, amphetamines trigger a signal cascade thought to involve PKC or MAPK that leads to the internalization of DAT molecules, which are normally expressed on the neuron’s surface [108]. Amphetamine on DAT also has a direct effect in the increased levels of secreted DA [109]. Lipophilic AMPH diffuses into the cytoplasm and the DA secretory vesicles disrupting the proton gradient established across the vesicle wall. This induces a leaky channel, and DA diffuses out into the cytoplasm. Additionally, AMPH causes a reversal of normal DA flow at the DAT. Instead of DA reuptake, in the presence of AMPH, a reversal in the mechanism of DAT occurs causing an outflow of DA released into the cytoplasm into the synaptic space changing it from a symporter to an antiporter-like functionality [110–112]. These mechanisms both result in less removal of DA from the synapse, increased signaling, which may underlie the pleasurable feelings elicited by these substances [113].

The DA transporter protein regulates DA-mediated neurotransmission by rapidly accumulating DA that has been released into the synapse [113]. Moreover, within 3 noncoding region of DAT1 lies a VNTR polymorphism [113]. There are two important alleles that may independently increase risk for RDS behaviors. The 9 repeat (9R) VNTR has been shown to influence gene expression and to augment transcription of the DA transporter protein [114]. Therefore, this results in an enhanced clearance of synaptic DA, yielding reduced levels of DA to activate postsynaptic neurons. Presence of the 9R VNTR has been linked to Substance Use Disorder [115], but not consistently [116]. Moreover, in terms of RDS behaviors, Cook et al. [117] was the first group that associated tandem repeats of the DAT gene in the literature. While there have been some inconsistencies associated with the earlier results, the evidence is mounting in favor of the view that the 10R allele of DAT is associated with high risk for ADHD in children and adults alike. Specifically, it was the non-additive association for the 10-repeat allele to be significant for hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms, but exploratory analyses of the non-additive association of the 9-repeat allele of DAT1 with HI and oppositional defiant disorder symptoms also was significant. However, Volkow’s [118] group found that 12 months of methylphenidate treatment significantly increased striatal DA transporter availability in ADHD (caudate, putamen, and ventral striatum) by 24 %, whereas there were no changes in control subjects retested at the 12-month interval.

Gamma Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) 1519T>CGABA(A)alpha6Gene

The role of GABA as the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter is the regulation of neuronal excitability throughout human central nervous system. First synthesized in 1883, as a plant and microbe metabolic product, it was not until 1950 that GABA was found to be an integral to brain functioning and directly responsible for muscle tone regulation [119].

GABA acts at the brains inhibitory synapses where it binds to specific transmembrane receptors. This binding in the plasma membrane of both pre- and postsynaptic neuronal processes opens the ion channels, discovered by Nobel Prize winner Erwin Neher in 1991. Ion channels allow chloride ions which are negatively charged into the cell or potassium ions which are positively charged to flow out of the cell. These actions change the transmembrane potential, causing hypo- or hyperpolarization. Polarization depends on the direction chloride flow. GABA is depolarizing (excitatory) when net chloride flows out of the cell and hyperpolarizing (inhibitory) when the net chloride flows into the cell. It is known that as the brain develops into adulthood the role of GABA changes from excitatory to inhibitory [120].

There are two known classes of GABA receptor: GABAA receptor, which is part, of a ligand-gated ion complex, and GABAB (G protein-coupled) metabotropic receptors that use intermediaries to open or close ion channels. GABAergic neurons that produce GABA have a mostly inhibitory action at receptors, although some GABAergic neurons, such as chandelier cells are able to excite their glutamatergic receptors or neurons counterparts [120–123].

In the metabolic pathway, called the GABA shunt, the enzyme l-glutamic acid decarboxylase and pyridoxal phosphate, the active form of vitamin B6, is used, as a cofactor, to synthesize GABA in the brain from glutamate, the principal excitatory neurotransmitter. In this process that converts glutamate into GABA [124, 125], the GABA transaminase enzyme catalyzes the conversion of 2-oxoglutarate and 4-aminobutanoic acid into glutamate and succinic semialdehyde. Then the enzyme succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase oxidizes succinic semialdehyde into succinic acid which enters the citric acid cycle as a usable source of energy [126].

Drugs, known as GABA analogues or GABAergic drugs act as allosteric modulators of GABA receptors, to increase the amount of available GABA and usually have, anti-anxiety, anti-convulsive, and relaxing effects [127, 128]. In general, GABA does not cross the blood-brain barrier [129]. At least one study suggests that blocking GABA increases the amount of DA released [130].

Genetics of GABA Receptor Gene Polymorphisms

GABA receptor genes have received some attention as candidates for drug use disorders. One reason for this is that the DA and GABA systems are functionally interrelated [112]. Research suggests that DA neurons projecting from the anterior VTA to the NAc are tonically inhibited by GABA through its actions at the GABAA receptor [131]. Moreover, it has been shown that alcohol [132] or opioids [133] enhancement of GABAergic (through GABAA receptor) transmission inhibits the release of DA in the mesocorticolimbic system. Thus, a hyperactive GABA system, by inhibiting DA release, could also lead to hypodopaminergic functioning. Because of this, GABA genes are of interest in the search for causes of drug use disorders. A dinucleotide repeat polymorphism of the GABA receptor β3 subunit gene (GABRB3) results in either the presence of the 181-bp G1 or 11 other repeats designated as non-G1 (NG1) [134]. Research indicates that the NG1 has an increased prevalence in children of alcoholics [134]. Presence of the NG1 has been associated with alcohol dependence [135, 136]. In addition, other GABA receptor genes have been associated with this disorder [137]. In fact, craving for alcohol and food has been studied in association with alcohol dependence and eating disorders, respectively. Thus, one subclass of the GABA receptor, 1519T>C GABA (A) alpha 6 has been associated with both ethanol dependence and weight gain. This gene polymorphism has been associated with hypo-cortisolism and perhaps abdominal obesity. Interestingly, the pathophysiology may involve various epigenetic factors, such as stress that destabilize the GABA-hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal systems in those with genetic vulnerability. In T-allele carriers, the change in craving for alcohol during treatment for alcohol dependence is negatively associated with changes in craving for food as well [137].

Expression patterns of GABAergic genes in rodent brains have been elucidated but not in humans. There are many GABAergic pathways and factor analysis involving global expression on 21 of these pathways has been performed. Specifically, postmortem data from hippocampus of eight alcoholics, eight cocaine addicts, and eight controls was evaluated to determine factor specificity for response to chronic alcohol/cocaine exposure. While RNA-Seq six gene expression factors were identified and loaded onto two factors, most genes loaded (≥0.5) onto one factor. These analyses led to the understanding that the chromosome 5 gene cluster was the largest factor (0.30 variance) and as such encodes the most common GABAA receptor, α1β2γ2, and genes encoding the α3β3γ2 receptor. Interestingly, within this factor, these genes were unresponsive to chronic alcohol/cocaine exposure. However, chronic alcohol/cocaine exposure affected chromosome 4 gene-cluster factor (0.14 variance) that encoded the α2β1γ1 receptor. Moreover, in both alcoholics and cocaine-dependent humans, two other factors (0.17 and 0.06 variance) included genes specifically involved in GABA synthesis and synaptic transport showed expression changes. It has been suggested that there is specificity of GABAergic gene groups, for response to chronic alcohol/cocaine exposure. Thus, understanding the nature of GABAergic gene group specificity could have therapeutic implications for combating stress-related craving and relapse [138].

Mu-Opioid Receptor Genes

Opioid receptors are a group of G-protein coupled receptors with opioids as ligands [139–141]. The original work on these receptors occurred in the late 1960s, with the first group being that of Avram Goldstein at Stanford [142]. The endogenous opioids are dynorphins, enkephalin, endorphins, endomophins, and nociception. In 1973, Pert and Snyder were first to publish a detailed binding study of what turned out to be the mu-opioid receptor using 3H-naloxone [143], although two other studies followed shortly after [144, 145]. The opioid receptors are ~40 % identical to somatostatin receptors (SSTRs). Opiate receptors are found in the spinal cord digestive tract and are distributed widely in the brain. The mu opiate receptor (OPRM) has high affinity for enkephalin, beta endorphins, and morphine.

An International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (IUPHAR) subcommittee has recommended that appropriate terminology for the four principal subtypes of opioid receptors the three classical (μ, δ, κ) receptors, and the non-classical (nociception) receptor, should be MOP, DOP, KOP, and NOP, respectively [146–148] (Table 3).

Genetics of the Mu Opiate Receptor Gene

The activity at the micro-opioid receptor is central to both pain responses and opioid addiction. The opioidergic hypothesis suggests variations at the opioid receptor mu 1 (OPRM1) gene locus associate with opiate addiction. Several SNPs in exon I contained in the OPRM1 gene, which encodes for mu-opioid receptor. The polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism method was used to genotype SNPs, A118G (rs 1799971) and C17T (rs 1799972) that have been associated with substance abuse. For the 118G allele, the opioid dependents (n = 126) had an approximately 2.5-fold higher frequency of 0.31 (odds ratio 3.501; CI(95 %) 2.212–5.555; P < 0.0001) while the control subjects (n = 156) showed a frequency of 0.12. For the C17T polymorphism, 0.83 seen in opioid dependents (n = 123; odds ratio of 0.555; CI(95 %) 0.264–1.147; P = 0.121) versus the controls (n = 57) showed a frequency of 0.89 for C allele. Thus, a significant association was observed between the 118G allele, and opioid dependence but no association was found with C17T polymorphism [149].

The effects of opiate drugs on pain experiences differ in humans. Recent twin studies documented individual differences, in several types of pain that are likely to be substantially determined by genetics. Genetic components to migraine pain susceptibility are documented in large twin studies, although in family studies have found substantial genetic heterogeneity in migraine. Humans μOR densities also differ. Both in vivo PET radioligand analyses and binding studies to postmortem brain samples suggest ranges of 30–50 %, or even larger, in individual differences in human μOR densities. Elucidation of the genetic basis for these differences based on receptor expression would advance substantially understanding of individual differences in and drug responses and nociceptive behaviors. The likelihood of high or low levels of expression in an individual can be predicted by information about μOR gene polymorphisms and may allow drug treatments to be individualized. These data could aid in optimization of dose ranges and selection of analgesic agents. Pain management for individuals with acute or long-term pain problems could be improved. These data could also add new therapeutic specificities and efficacies to this well-established opiate drug class, still a major weapon for amelioration of pain states [150].