Abstract

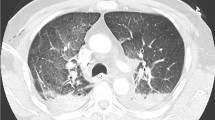

Iatrogenic consequences of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) include sternal or rib fractures, pulmonary bone marrow embolisms (BME) and fat embolisms (FE). This report aimed to analyze the frequency and intensity of pulmonary BME and FE in fatal cases receiving final CPR efforts with the use of automated chest compression devices (ACCD) or manual chest compressions (mCC). The study cohort (all cardiac causes of death, no ante-mortem fractures) consisted of 15 cases for each group ‘ACCD’, ‘mCC’ and ‘no CPR’. Lung tissue samples were retrieved and stained with hematoxylin eosin (n = 4 each) and Sudan III (n = 2 each). Evaluation was conducted microscopically for any existence of BME or FE, the frequency of BME-positive vessels, vessel size for BME and the graduation according to Falzi for FE. The data were compared statistically using non-parametric analyses. All groups were matched except for CPR duration (ACCD > mCC) but this time interval was linked to the existence of pulmonary BME (p = 0.031). Both entities occur in less than 25% of all cases following unsuccessful CPR. BME was only detectable in CPR cases, but was similar between ACCD and mCC cases for BME frequency (p = 0.666), BME intensity (p = 0.857) and the size of BME-affected pulmonary vessels (p = 0.075). If any, only mild pulmonary FE (grade I) was diagnosed without differences in the CPR method (p = 0.624). There was a significant correlation between existence of BME and FE (p = 0.043). Given the frequency, intensity and size of pulmonary BME and FE following CPR, these conditions may unlikely be considered as causative for death in case of initial survival but can be found in lower frequencies in autopsy histology.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Soar J, Nolan JP, Böttiger BW, Perkins GD, Lott C, Carli P, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 3. Adult advanced life support. Resuscitation. 2015;95:100–47.

Hashimoto Y, Moriya F, Furumiya J. Forensic aspects of complications resulting from cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Legal Med. 2007;9:94–9.

Buschmann C, Schulz T, Toskos M, Kleber C. Emergency medicine techniques and the forensic autopsy. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2013;9:48–67.

Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM, Berg RA, Bhanji F, Biarent D, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein resuscitation registry templates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2015;132:1286–300.

Truhlar A, Deakin CD, Soar J, Khalifa GE, Alfonzo A, Bierens JJ, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines for resuscitation 2015: section 4. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances. Resuscitation. 2015;95:148–201.

Marti J, Hulme C, Ferreira Z, Nikolova S, Lall R, Kaye C, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a mechanical compression device in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2017;117:1–7.

Newberry R, Redman T, Ross E, Ely R, Saidler C, Arana A, et al. No benefit in neurologic outcomes of survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with mechanical compression device. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22:338–44.

Ondruschka B, Baier C, Hartwig T, Gräwert S, Böhm L, Dreßler J, et al. Leitlinienadhärenz bei frustran verlaufenden Reanimationen mit automatischen Reanimationsgeräten. Notarzt. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1005/a-0669-9207.

Lardi C, Egger C, Larribau R, Niquille M, Mangin P, Fracasso T. Traumatic injuries after mechanical cardiopulmonary resuscitation (LUCAS™2): a forensic autopsy study. Int J Legal Med. 2015;129:1035–42.

Smekal D, Johansson J, Huzevka T, Rubertsson S. No difference in autopsy detected injuries in cardiac arrest patients treated with manual chest compressions compared with mechanical compressions with the LUCAS device – a pilot study. Resuscitation. 2009;80:1104–7.

Koster RW, Beenen LF, van der Boom EB, Spijkerboer AM, Tepaske R, van der Wal AC, et al. Safety of mechanical chest compression devices AutoPulse and LUCAS in cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial for non-inferiority. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:4006–13.

Arai H. Pulmonary bone marrow embolism: a review of 350 necropsy cases. Pathol Int. 1979;29:911–31.

Eriksson EA, Pellegrini DC, Vanderkolk WE, Minshall CT, Fakhry SM, Cohle SD. Incidence of pulmonary fat embolism at autopsy: an undiagnosed epidemic. J Trauma. 2011;71:312–5.

Dettmer M, Willi N, Thiesler T, Ochsner P, Cathomas G. The impact of pulmonary bone component embolism: an autopsy study. J Clin Pathol. 2014;67:370–4.

Carstens PH. Pulmonary bone marrow embolism following external cardiac massage. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1969;76:510–4.

Jarmer J, Ampanozi G, Thali MJ, Bolliger SA. Role of survival time and injury severity in fatal pulmonary fat embolism. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2017;38:74–7.

Baker PL, Pazell JA, Peltier LF. Free fatty acids, catecholamines, and arterial hypoxia in patients with fat embolism. J Trauma. 1971;11:1026–30.

Schinella RA. Bone marrow emboli. Their fate in the vasculature of the human lung. Arch Pathol. 1973;95:386–91.

Falzi G, Henn R, Spann W. Über pulmonale Fettembolie nach Traumen mit verschieden langer Überlebenszeit. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1964;21:978–81.

Janssen W. Forensic histology. Lübeck: Schmidt-Römhild; 1977. p. 111–50.

Krämer M, Penners BM. Postmortem tissue embolisms. Report of 3 cases. Arch Kriminol. 1989;183:29–36.

Barzdo M, Berent J, Markuszewski L, Szram S. A coronary artery crossed embolism of bone-marrox origin: proof of connections between pulmonary arteries and veins. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;149:47–50.

Yamamoto M. Pathology of experimental pulmonary bone marrow embolism. Initial lesions of the rabbit lung after intravenous infusion of allogeneic bone marrow with special reference to its pathogenesis. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1985;35:45–69.

Brinkmann B, Borgner M, von Bülow M. Fat embolism of the lungs as the cause of death. Etiology, pathogenesis and reasoning. Z Rechtsmed. 1976;78:255–72.

Voisard MX, Schweitzer W, Jackowski C. Pulmonary fat embolism - a prospective study within the forensic autopsy collective of the Republic of Iceland. J Forensic Sci. 2013;S1:S105–11.

Baringer JR, Salzmann EW, Jones WA, Friedlich AL. External cardiac massage. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:62–5.

Garvey JW, Zak FG. Pulmonary bone marrow emboli in patients receiving external cardiac massage. JAMA. 1964;187:59–60.

Yanoff M. Incidence of bone-marrow embolism due to closed-chest cardiac massage. N Engl J Med. 1963;269:837–9.

Jackson CT, Greendyke RM. Pulmonary and cerebral fat embolism after closed chest cardiac massage. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:25.

Schneider V, Kluge E. Pulmonary fat embolism after external cardiac massage. Beitr Gerichtl Med. 1971;28:76.

Flach PM, Ross SG, Bolliger SA, Ampanozi G, Hatch GM, Schön C, et al. Massive systemic fat embolism detected by postmortem imaging and biopsy. J Forensic Sci. 2012;57:1376–80.

Sinicina I, Pankratz H, Schöpfer J. Unusual cases of pulmonary embolism. Rechtsmedizin. 2018;28:214–8.

Dzieciol J, Kemona A, Gorska M, Barwijuk M, Sulkowski S, Kozielec Z, et al. Widespread myocardial and pulmonary bone marrow embolism following cardiac massage. Forensic Sci Int. 1992;56:195–9.

Jorens PG, Van Marck EV, Snoeckx A, Parizel PM. Nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:452–74.

Jenny-Möbius U, Bruder E, Stallmach T. Recognition and significance of pulmonary bone embolism. Int J Legal Med. 1999;112:195–7.

Blumenthal R, Saayman G. Bone marrow embolism to the lung in electrocution: two case reports. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2014;35:170–1.

Rappaport H, Raum M, Horrell JB. Bone marrow embolism. Am J Pathol. 1951;27:407–33.

Eckardt P, Raez LE, Restrepo A, Temple JD. Pulmonary bone marrow embolism in sickle cell disease. South Med J. 1999;92:245–7.

Hawley DA, McCarthy LJ. Sickle cell disease: two fatalities due to bone marrow emboli in patients with acute chest syndrome. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2009;30:69–71.

Targueta EP, Hirano ACG, de Campos FPF, Martines JADS, Lovisolo SM, Felipe-Silva A. Bone marrow necrosis and fat embolism syndrome: a dreadful complication of hemoglobin sickle cell disease. Autops Case Rep. 2017;7:42–50.

Kettner M, Ramsthaler F, Schmidt P, Padosch SA. Acute pulmonary embolism. Forensic assessment of accusations of diagnostic and treatment errors. Rechtsmedizin. 2013;23:255–62.

Margiotta G, Coletti A, Severini S, Tommolini F, Lancia M. Medico-legal aspects of pulmonary thromboembolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:407–18.

Zichner L. The importance of pulmonary embolism by bone fragments and bone marrow. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1970;326:367–79.

Pollak S, Reiter C, Stellwag-Carion C. 2-stage rupture of the liver as a complication of external heart massage. Z Rechtsmed. 1984;92:67–75.

Lau G. Pulmonary cartilage embolism: fact or artefact? Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1995;16:51–3.

Orlowski JP, Julius CJ, Petras RE, Porembka DT, Gallagher JM. The safety of intraosseous infusions: risks of fat and bone marrow emboli to the lungs. Ann Emerg Med. 1989;18:1062–7.

Fiallos M, Kissoon N, Abdelmoneim T, Johnson L, Murphy S, Lu L, et al. Fat embolism with the use of intraosseous infusion during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Am J Med Sci. 1997;314:73–9.

Maxeiner H. Congestion bleedings of the face and cardiopulmonary resuscitation – an attempt to evaluate their relationship. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;117:191–8.

Maxeiner H, Jekat R. Resuscitation and conjunctival petechial hemorrhages. J Forensic Legal Med. 2010;17:87–91.

Brunner P, Schellmann B. Is there a topography of posttraumatic fat embolism? Histological studies on lung whole-organ sections. Beitr Gerichtl Med. 1979;37:153–7.

Havig O, Grüner OP. Pulmonary bone marrow embolism. A histological study of a non-selected autopsy material. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A. 1973;81:276–80.

Meaney PA, Bobrow BJ, Mancini ME, Christenson J, de Caen AR, Bhanji F, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation quality: improving cardiac resuscitation outcomes both inside and outside the hospital: a consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:417–35.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Miss Cornelia Pietschmann for her skillful help in the histology laboratory and Miss Aqeeda Singh for proofreading the paper as a native speaker.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the given study.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig, Germany (code: 104/17-ek).

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ondruschka, B., Baier, C., Bernhard, M. et al. Frequency and intensity of pulmonary bone marrow and fat embolism due to manual or automated chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 15, 48–55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-018-0044-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-018-0044-1