Opinion statement

Melanoma has several clinically and pathologically distinguishable subtypes, which also differ genetically. Mutation patterns vary among different melanoma subtypes, and efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors differs depending on the subtype of melanoma. In spite of the recent revolution of systemic therapies for advanced melanoma, access to innovative agents is still restricted in many countries. This review article aimed to describe the epidemiology and current status of systemic therapies for melanoma in Japan, where melanoma is rare, but access to innovative agents is available. Acral and mucosal melanomas, which are common in Asian populations, predominantly occur in sun-protected areas and share several biological features. Both the melanomas harbor KIT mutation in approximately 15% of the cases; BRAF or NRAS mutation is found in approximately 10–15% of acral melanoma, but these mutations are less frequent in mucosal melanoma. Combined use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors is one of the standards of care for patients with advanced BRAF-mutant melanoma. In patients with melanoma harboring KIT mutation in exon 11 or 13, KIT inhibitors can be a treatment option; however, none of them have been approved in Japan. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors are expected to be less effective against acral and mucosal melanomas because their somatic mutation burden is lower than those in non-acral cutaneous melanomas. A recently completed phase II trial of nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy in 30 Japanese patients with melanoma, including seven with acral and 12 with mucosal melanoma, demonstrated an objective response rate of 43%. Regarding oncolytic viruses, canerpaturev (C-REV, also known as HF10) and talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) are currently under review in early phase trials. In the adjuvant setting, dabrafenib plus trametinb combination, nivolumab monotherapy, and pembrolizumab monotherapy were approved in July, August, and December 2018 in Japan, respectively. However, most of the adjuvant phase III trials excluded patients with mucosal melanoma. A phase III trial of adjuvant therapy with locoregional interferon (IFN)-β versus surgery alone is ongoing in Japan (JCOG1309, J-FERON), in which IFN-β is injected directly into the site of the primary tumor postoperatively, so that it would be drained through the untreated lymphatic route to the regional node basin. After the recent approval of these new agents, the JCOG1309 trial will be revised to focus on patients with stage II disease. In conclusion, acral and mucosal melanomas have been treated based on the available medical evidence for the treatment of non-acral cutaneous melanomas. Considering the differences in genetic backgrounds and therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy, specialized therapeutic strategies for these subtypes of melanoma should be established in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic therapies for advanced melanoma have been dramatically revolutionized by the development of targeted therapies, such as BRAF and MEK inhibitors, and immunotherapies, such as anti-PD-1 antibodies alone or in combination with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Although these new agents have become the recommended up-front therapies in several international melanoma guidelines, a recently reported web-based worldwide survey revealed that access to these innovative agents is still restricted in many countries [1].

Melanoma has the following clinically distinguishable subtypes: cutaneous, mucosal, uveal, and unknown primary melanomas. Cutaneous melanomas are further categorized into superficial spreading melanoma (SSM), nodular melanoma (NM), lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM), and acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) [2] based on their clinical and pathological features. Recent advances in molecular biology have revealed that these subtypes are also genetically distinct [3]. Of these subtypes, ALM and mucosal melanoma occur in sun-protected areas and share several biological characteristics.

In Japan, a combination of dabrafenib and trametinib, pembrolizumab monotherapy, and nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab are currently employed for the treatment of melanoma; and there is a high incidence of ALM and mucosal melanoma in the Japanese population [4••]. Therefore, this review article aimed to describe the epidemiology and current status of systemic therapies for melanoma in Japan, where melanoma is rare, but access to innovative agents is available.

Epidemiology of melanoma in Japan

According to nationwide statistical surveys on skin malignancies in Japan, among the types of skin cancers including both melanomas and non-melanoma skin cancers, basal cell carcinoma (BCC) was the most common, followed by cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), cutaneous melanoma, and extra-mammary Paget’s disease. When carcinoma in situ is included, such as actinic keratosis and Bowen’s disease, cSCC would be the most common [5]. Melanoma is the third most common type of skin cancer, but comprising approximately half of all deaths from skin cancers in Japan; thus, it is considered to be the most common cause of death from skin cancers.

A recent statistics according to Hospital-Based Cancer Registries showed that the proportion relative to all types of melanoma and the crude incidence rate per 100,000 person-years for each subtype were as follows: cutaneous, 80.5% and 1.75; mucosal, 14.8% and 0.32; uveal, 2.9% and 0.064; and unknown primary melanoma, 1.8% and 0.039, respectively [4••]. The greater proportion of mucosal melanoma among all melanomas has been considered to be due to the low incidence of non-acral cutaneous melanoma in Asian populations. However, the study demonstrated that the incidence rate of mucosal melanoma might also be higher in Asian populations. Mucosal melanoma is primarily located in the head and neck regions in 52%, gastrointestinal tract in 28%, female genitalia in 9%, conjunctiva in 6%, and others in 5% of cases [4••]. The ALM subtype of cutaneous melanoma was observed in 41%, NM in 20%, SSM in 19%, LMM in 7%, and unknown or unclassified in 13% of cases [5] (Fig. 1). Only 4% of cutaneous melanomas are stage IV at diagnosis, whereas the proportion of patients with metastatic tumor at diagnosis in mucosal melanoma is as high as 25% [4••]; thus, mucosal melanoma comprised nearly 40% of all metastatic melanomas in Japan.

Primary sites and subtypes of melanoma in Japan, created from the statistics based on Hospital-Based Cancer Registries and nationwide statistical surveys [4, 5]. The numbers in round brackets refer to proportion among all types of melanoma. The numbers in square brackets refer to proportion among each subtype of melanoma. Abbreviations: ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma; NM, nodular melanoma; SSM, superficial spreading melanoma; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; GI, gastrointestinal

Targeted therapies for metastatic melanoma

Researchers with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Network identified four genomic subgroups of melanoma: BRAF, NRAS, NF1, and triple wild-type [6]. The mutation patterns vary among the melanoma subtypes, both in terms of the total numbers of mutations and the types of driver oncogenes [7, 8•]. KIT mutations were found in approximately 15% of acral and mucosal melanomas, and BRAF or NRAS mutation was found in approximately 10–15% of acral melanoma, but was less frequent in mucosal melanoma [8•, 9]. Acral and mucosal subtypes of melanoma are predominant in the Japanese population, and the overall detection rates of BRAF, NRAS, and KIT mutations are approximately 30%, 12%, and 13%, respectively [10, 11]. Since subungual melanoma specimens obtained from patients undergoing digital amputation are unlikely to have been included in the aforementioned studies due to the decalcification procedures in the bone, the actual detection rate of BRAF mutations in Japanese patients with melanoma may be lower than that reported in those studies.

In acral and mucosal melanomas, KIT has been considered to be one of the reasonable therapeutic targets [12, 13]. A KIT inhibitor, imatinib, demonstrated its clinical efficacy in phase II studies involving patients with KIT mutations [14,15,16], although it was not effective in another clinical trials that did not include KIT mutation or amplification in the eligibility criteria [17,18,19]. In a phase II study of 25 patients, six (24%) responders had a mutation with either KIT exon 11 or 13 [14]. In another phase II study of 43 patients, ten (23%) patients responded to imatinib, of these, nine had KIT gene mutations (exon 11 in six and exon 13 in three patients) and the other one had KIT gene amplification [15]. In a phase II study in which seven (29%) of 24 patients responded to imatinib, seven of 13 patients with KIT mutations responded, whereas none of 11 patients with KIT amplification responded [16]. At present, imatinib is likely most effective in patients with melanoma harboring KIT mutations (exon 11 or 13); however, the response rate is not that high, and a durable response seems not to be expected. In Japan, clinical studies focusing on patients with KIT mutations have not yet been conducted.

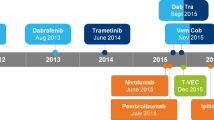

The activated BRAF-mutated kinase can be inhibited by BRAF inhibitors, and its downstream MEK activation can be inhibited by MEK inhibitors. Combined use of BRAF and MEK inhibitors can delay the emergence of drug resistance against BRAF inhibitors and can also reduce the risk of occurrence of skin toxicities such as cSCC. In patients with advanced melanomas harboring BRAF V600 mutation, three different combinations of BRAF plus MEK inhibitors have been shown to yield superior clinical outcomes over BRAF inhibitor alone: dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib (COMBI-d) [20,21,22], dabrafenib plus trametinib versus vemurafenib (COMBI-v) [23], vemurafenib plus cobimetinib versus vemurafenib (coBRIM) [24, 25], and encorafenib plus binimetinib versus encorafenib or vemurafenib (COLUMBUS) [26, 27]. In Japan, clinical studies on vemurafenib plus cobimetinib combination therapy have not been conducted, but a phase I/II study of vemurafenib monotherapy has been carried out [28]. A total of 11 patients with advanced melanoma were enrolled, with an overall response rate of 55%, and no patients developed cSCC. Vemurafenib monotherapy was approved in Japan in December 2014. Subsequently, a phase I/II trial of dabrafenib plus trametinib combination therapy was carried out on 12 patients with advanced melanoma [29]. The overall response rate was 83%, and the most common adverse event (AE) was pyrexia, which was observed in 75% of the participants. The efficacy and toxicities observed in this study were almost comparable to those reported in the international phase III studies. Dabrafenib plus trametinib combination therapy in the metastatic setting was approved in March 2016 in Japan. Japanese institutions also participated in the COLUMBUS trial, and the combination of encorafenib plus binimetinib was approved in January 2019 (Table 1). Some clinical trials comparing sequential regimens of BRAF plus MEK inhibitors followed by nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination with the reverse sequence are ongoing. Other clinical trials on concurrent BRAF plus MEK inhibitors with anti-PD-1 or anti-PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibodies are also ongoing. Of these, Japanese institutions are currently involved in the COMBI-i trial that evaluates BRAF plus MEK inhibitors along with the concurrent use of anti-PD-1 antibody (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02967692).

NRAS mutation is found in approximately 15% of acral melanoma, but it is rarely seen in mucosal melanoma [8•]. In patients with NRAS-mutant melanoma, a phase III randomized controlled trial assigned either MEK inhibitor, binimetinib, or dacarbazine (DTIC) at a ratio of 2:1 (NEMO). Japanese institutions also participated in the NEMO trial. The results revealed a significantly better median progression-free survival (PFS) in the binimetinib group (2.8 vs. 1.5 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.47–0.80; p < 0.001), but no statistically significant difference was noted in the median overall survival (OS) between the groups (11.0 vs. 10.1 months; HR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.75–1.33; p = 0.499) [63]. Other clinical trials of combination therapy, such as MEK inhibitor plus cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor or MEK inhibitor plus anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody, are ongoing; however, no Japanese institutions are involved.

Immunotherapies for metastatic melanoma

The efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors, such as ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) and nivolumab or pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1 antibodies), have been demonstrated to be superior to that of the conventional agents. Pembrolizumab was associated with a significantly prolonged PFS and OS as compared to ipilimumab in the KEYNOTE-006 randomized phase III trial [45, 46], and nivolumab followed by ipilimumab therapy was associated with improved outcomes as compared to treatment in the reverse sequence in the CheckMate 064 randomized phase II trial [64]. The clinical outcomes of nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab were shown to be superior to that of ipilimumab monotherapy in the CheckMate 067 randomized phase III trial [48, 49]. Therefore, nivolumab monotherapy, pembrolizumab monotherapy, and nivolumab combined with ipilimumab are the currently available first choices of systemic immunotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma.

The efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitor differs depending on the subtype of melanoma; for example, the efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy on metastatic uveal melanoma has been shown to be limited [65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. Melanomas occurring in sun-exposed skin tend to have higher numbers of mutations, whereas those occurring in sun-protected areas, such as mucosal or acral melanomas, have significantly lower total numbers of single-nucleotide variants [72••]. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors are known to be more effective against tumors with a higher mutation burden; therefore, they are expected to be less effective against acral and mucosal melanomas. A multi-institutional retrospective study evaluated the clinical efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibody in 25 and 35 patients with acral and mucosal melanoma, respectively. In this study, 51 patients (85%) had a previous history of systemic therapies, including ipilimumab. The objective response rate and median PFS were 32% and 4.1 months in patients with acral melanoma, and 23% and 3.9 months in those with mucosal melanoma, respectively [73]. Another study evaluated the efficacy and safety of nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab for mucosal melanoma, using data pooled from several clinical trials of nivolumab monotherapy or nivolumab plus ipilimumab combination therapy. The objective response rate and median PFS in nivolumab monotherapy in patients with mucosal melanoma were 23% and 3.0 months and those in the nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy were 37% and 5.9 months, respectively [74]. In a post hoc analysis of clinical trials on pembrolizumab monotherapy, the objective response rate, median PFS, and median OS associated with pembrolizumab monotherapy in 84 patients with mucosal melanoma were 19%, 2.8 months, and 11.3 months, respectively [75]. These studies consistently demonstrated a certain efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors against acral or mucosal melanoma; however, these therapies appear to be somewhat less efficacious than those against non-acral cutaneous melanomas.

In Japan, a phase II trial of ipilimumab 10 mg/kg plus dacarbazine was terminated early due to the high frequency of liver toxicity [40]. A subsequent phase II trial of ipilimumab 3 mg/kg monotherapy was completed, which showed an acceptable tolerability. The proportion of patients who developed immune-related AE in this trial was 60%. The best overall response and disease control rates were 10% and 20%, respectively [38]. Phase II trials of nivolumab (2 mg/kg, every 3 weeks) in patients with past history of systemic therapies [42] and nivolumab (3 mg/kg, every 2 weeks) in previously untreated patients [44] were conducted; in the former trial, in the second-line setting, 35 evaluable patients were enrolled. The best overall response rate was 29%, median PFS was 5.6 months, and median OS was 18.0 months. Grades 3–4 drug-related AEs were observed in 31% of patients [42]. In the latter trial, in the first-line setting, 24 patients were enrolled. The best overall response rate was 35%, median PFS was 5.9 months, and median OS was not reached. Grades 3–4 drug-related AEs were observed in 13% of patients [44]. A phase Ib trial of pembrolizumab was also carried out on 42 patients with 0–2 prior lines of systemic therapy, including 12 patients with ALM and eight patients with mucosal melanoma [47]. Among the 37 evaluable patients, the confirmed overall response rate was 24% in those with cutaneous melanoma and 25% in those with mucosal melanoma. A phase II trial of nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy was recently completed [50•]. A total of 30 patients, including seven with acral and 12 with mucosal melanoma, were enrolled. The overall response rate was 43%, and neither the median PFS nor OS was reached. Grades 3–4 and serious AEs occurred in 23 (77%) and 20 (67%) patients, respectively. This study confirmed a certain efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in previously untreated Japanese patients with advanced melanoma, including rare subtypes (Table 1). Although the clinical efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors has been shown to be somewhat lower in Japanese patients with melanoma than those in Caucasians, whether the differences are due to melanoma subtypes alone or also due to the ethnicity remains unclear.

Oncolytic viruses are injected directly into the tumor to promote the release of tumor-associated antigens and mediate the host’s antitumor immunity. Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) is a genetically modified herpes simplex virus-1, and T-VEC monotherapy demonstrated a durable response rate of 16% in the OPTiM phase III trial [76]. In that trial, responses are also observed in uninjected lesions including visceral sites [77]. In Japan, a multicenter phase I trial of T-VEC for melanoma is ongoing (NCT03064763). Another oncolytic virus, canerpaturev (C-REV, also known as HF10), is an attenuated, replication-competent mutant strain of herpes simplex virus-1. In Japan, a single-institutional phase I study of C-REV monotherapy was completed (NCT02428036), and a subsequent multicenter phase II study of C-REV combined with ipilimumab has also been completed (NCT03153085).

Adjuvant therapies for melanoma

Results of several clinical trials on new agents, such as immune-checkpoint inhibitors and BRAF/MEK inhibitors, in the adjuvant setting have been published. The EORTC18071 trial, a randomized phase III trial of adjuvant therapy with ipilimumab administered at the dose of 10 mg/kg in patients with postoperative stage III cutaneous melanoma, showed a significantly longer OS in the ipilimumab arm than in the placebo arm [54, 55]. However, adjuvant ipilimumab administered at 10 mg/kg was associated with high frequency of toxicities, including five (1.1%) treatment-related deaths. The COMBI-AD trial, in which patients with stage III disease (stage IIIA melanoma with a tumor deposit of > 1 mm diameter within the sentinel lymph node (SLN)) were assigned to either dabrafenib plus trametinib or placebo, showed a significantly longer relapse-free survival (RFS) in the dabrafenib plus trametinib treatment arm (HR 0.47; 95% CI, 0.39 to 0.58; p < 0.001) [52, 53]. The CheckMate238 trial, in which patients with stage III disease (stage IIIA melanoma with a tumor deposit of > 1 mm in diameter within the SLN) were assigned to either nivolumab 3 mg/kg or ipilimumab 10 mg/kg, showed a significantly longer RFS and more favorable toxicity profile in the nivolumab treatment arm (HR 0.65; 97.56% CI, 0.51 to 0.83; p < 0.001) [57]. Subsequently, the EORTC1325/KEYNOTE-054 trial, in which patients with stage III disease (stage IIIA melanoma with a tumor deposit of > 1 mm diameter within the SLN) were assigned to either pembrolizumab 200 mg/body or placebo, showed a significantly longer RFS in the pembrolizumab treatment arm (HR 0.57; 98.4% CI, 0.43 to 0.74; p < 0.001) [58]. Japanese institutions have participated in the COMBI-AD, CheckMate238, and EORTC1325/KEYNOTE-054 trials. In Japan, dabrafenib plus trametinib combination, nivolumab monotherapy, and pembrolizumab monotherapy were approved as adjuvant therapy in July, August, and December 2018, respectively.

Among these recent trials in the adjuvant setting, patients with mucosal melanoma were included only in the CheckMate238 trial, although the number of patients included was limited. In patients with mucosal melanoma, results of a phase II trial of adjuvant therapy have been published from China [78]. Patients with resected mucosal melanoma were randomized to observation, high-dose interferon (IFN)-alfa, or chemotherapy with temozolomide plus cisplatin. Patients in the chemotherapy arm showed a significantly longer RFS and OS than those in either the high-dose IFN-alfa or observation arm. Results of a subsequently conducted phase III trial comparing high-dose IFN-alfa with temozolomide plus cisplatin were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2018; they confirmed the superiority, in terms of the RFS, of temozolomide plus cisplatin over high-dose IFN-alfa [79]. However, no formal confirmatory trials of immune-checkpoint inhibitors for mucosal melanoma have been reported yet.

Before the recent breakthroughs in systemic therapies for melanoma, IFNs were the most frequently used agents in the adjuvant setting. High-dose or pegylated IFN-alfa has been shown to improve the RFS; however, its efficacy in terms of the OS is marginal, and the incidence of severe AEs is relatively high [59, 60, 80,81,82]. In Japan, pegylated-IFN-alfa was approved in May 2015 after the completion of a phase I trial [61]. Another type I IFN, IFN-β, has also been used for melanoma in Japan. The lymphatic route between the primary site and the regional node basin usually remains untreated even after a definitive curative surgery because the primary site of cutaneous melanoma is often located away from its regional node basin. To improve the outcome of adjuvant IFN therapy and lower its toxicity, the Dermatologic Oncology Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG-DOG) began a phase III randomized controlled trial of adjuvant therapy with locoregional IFN-β versus surgery alone in patients with stage II/III cutaneous melanoma (JCOG1309, J-FERON trial) in May 2015 [62•]. In this trial, IFN-β was injected directly into the surgical site of the primary tumor postoperatively, similar to the procedure used for SLN biopsy, so that it would be drained through the untreated lymphatic route to the regional node basin. The JCOG-DOG hypothesized that the locally injected IFN-β would reach clinically occult residual melanoma cells along the untreated lymphatic route and possibly induce systemic immunity. After the recent approval of new agents in the adjuvant setting in Japan, such as dabrafenib plus trametinib combination, nivolumab monotherapy, or pembrolizumab monotherapy, the JCOG-DOG plans to revise the protocol to focus on patients with stage II disease.

Conclusions

Acral and mucosal melanomas have been treated based on the available medical evidence for the treatment of non-acral cutaneous melanomas. Considering the differences in genetic backgrounds and therapeutic efficacy of immunotherapy, specialized therapeutic strategies for these subtypes of melanoma should be established in the future.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Kandolf Sekulovic L, Guo J, Agarwala S, Hauschild A, McArthur G, Cinat G, et al. Access to innovative medicines for metastatic melanoma worldwide: Melanoma World Society and European Association of Dermato-oncology survey in 34 countries. Eur J Cancer. 2018;104:201–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.013.

Teramoto Y, Keim U, Gesierich A, Schuler G, Fiedler E, Tuting T, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma: a skin cancer with unfavourable prognostic features. A study of the German central malignant melanoma registry (CMMR) in 2050 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(2):443–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15803.

Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(20):2135–47. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050092.

•• Tomizuka T, Namikawa K, Higashi T. Characteristics of melanoma in Japan: a nationwide registry analysis 2011–2013. Melanoma Res. 2017;27(5):492–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000375 This is the first nation-wide survey based on Hospital-Based Cancer Registries to demonstrate the epidemiology of all types of melanoma in Japan.

Ishihara K, Saida T, Otsuka F, Yamazaki N, Prognosis, Statistical Investigation Committee of the Japanese Skin Cancer S. Statistical profiles of malignant melanoma and other skin cancers in Japan: 2007 update. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13(1):33–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-007-0751-1.

Cancer Genome Atlas N. Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161(7):1681–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044.

Sullivan RJ, Fisher DE. Understanding the biology of melanoma and therapeutic implications. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28(3):437–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2014.02.007.

• Davis EJ, Johnson DB, Sosman JA, Chandra S. Melanoma: what do all the mutations mean? Cancer. 2018;124(17):3490–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31345 This article nicely described an overview of common mutations seen in melanoma and their clinical and biological implications.

Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(26):4340–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984.

Yamazaki N, Tanaka R, Tsutsumida A, Namikawa K, Eguchi H, Omata W, et al. BRAF V600 mutations and pathological features in Japanese melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2015;25(1):9–14. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000091.

Sakaizawa K, Ashida A, Uchiyama A, Ito T, Fujisawa Y, Ogata D, et al. Clinical characteristics associated with BRAF, NRAS and KIT mutations in Japanese melanoma patients. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80(1):33–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.07.012.

Nakamura Y, Fujisawa Y. Diagnosis and management of acral lentiginous melanoma. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2018;19(8):42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-018-0560-y.

Oba J, Kim SH, Wang WL, Macedo MP, Carapeto F, McKean MA, et al. Targeting the HGF/MET Axis counters primary resistance to KIT inhibition in KIT-mutant melanoma. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/PO.18.00055.

Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD, Chapman PB, Roman RA, Teitcher J, et al. KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2327–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.746.

Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, Flaherty KT, Xu X, Zhu Y, et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(21):2904–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9275.

Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, Fletcher JA, Zhu M, Marino-Enriquez A, et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3182–90. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7836.

Ugurel S, Hildenbrand R, Zimpfer A, La Rosee P, Paschka P, Sucker A, et al. Lack of clinical efficacy of imatinib in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2005;92(8):1398–405. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602529.

Wyman K, Atkins MB, Prieto V, Eton O, McDermott DF, Hubbard F, et al. Multicenter phase II trial of high-dose imatinib mesylate in metastatic melanoma: significant toxicity with no clinical efficacy. Cancer. 2006;106(9):2005–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21834.

Kim KB, Eton O, Davis DW, Frazier ML, McConkey DJ, Diwan AH, et al. Phase II trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(5):734–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604482.

Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1877–88. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1406037.

Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, Larkin J, et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):444–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60898-4.

Long GV, Flaherty KT, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Levchenko E, de Braud F, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib versus dabrafenib monotherapy in patients with metastatic BRAF V600E/K-mutant melanoma: long-term survival and safety analysis of a phase 3 study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1631–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx176.

Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, Rutkowski P, Mackiewicz A, Stroiakovski D, et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(1):30–9. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1412690.

Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Maio M, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–76. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1408868.

Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dreno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Di Giacomo AM, et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAF(V600)-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(9):1248–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30122-X.

Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, Arance A, Mandala M, Liszkay G, et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(5):603–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30142-6.

Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, Arance A, Mandala M, Liszkay G, et al. Overall survival in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma receiving encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(10):1315–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30497-2.

Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Sugaya N, Uhara H. Phase I/II study of vemurafenib in patients with unresectable or recurrent melanoma withBRAFV600mutations. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):661–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.12873.

Yamazaki N, Tsutsumida A, Takahashi A, Namikawa K, Yoshikawa S, Fujiwara Y, et al. Phase 1/2 study assessing the safety and efficacy of dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy in Japanese patients with BRAF V600 mutation-positive advanced cutaneous melanoma. J Dermatol. 2018;45(4):397–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.14210.

Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, Haanen JB, Ascierto P, Larkin J, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1103782.

McArthur GA, Chapman PB, Robert C, Larkin J, Haanen JB, Dummer R, et al. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAF (V600E) and BRAF(V600K) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):323–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70012-9.

Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Sugaya N, Uhara H. Phase I/II study of vemurafenib in patients with unresectable or recurrent melanoma with BRAF(V) (600) mutations. J Dermatol. 2015;42(7):661–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.12873.

Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, Jouary T, Gutzmer R, Millward M, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):358–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60868-X.

Fujiwara Y, Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Yoshikawa S, Yamamoto N, Tsutsumida A, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic profile of dabrafenib in Japanese patients with BRAF (V600) mutation-positive solid tumors: a phase 1 study. Investig New Drugs. 2018;36(2):259–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-017-0502-8.

Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, Nathan P, Garbe C, Milhem M, et al. Improved survival with MEK inhibition in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):107–14. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1203421.

Kasuga A, Nakagawa K, Nagashima F, Shimizu T, Naruge D, Nishina S, et al. A phase I/Ib study of trametinib (GSK1120212) alone and in combination with gemcitabine in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Investig New Drugs. 2015;33(5):1058–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-015-0270-2.

Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–23. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1003466.

Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Uhara H, Fukushima S, Uchi H, Shibagaki N, et al. Phase II study of ipilimumab monotherapy in Japanese patients with advanced melanoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76(5):997–1004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2873-x.

Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, O'Day S, Weber J, Garbe C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2517–26. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1104621.

Yamazaki N, Uhara H, Fukushima S, Uchi H, Shibagaki N, Kiyohara Y, et al. Phase II study of the immune-checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in Japanese patients with previously untreated, unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76(5):969–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-015-2870-0.

Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D, Hodi FS, Gutzmer R, Neyns B, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):375–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8.

Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Uhara H, Iizuka H, Uehara J, Otsuka F, et al. Cytokine biomarkers to predict antitumor responses to nivolumab suggested in a phase 2 study for advanced melanoma. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(5):1022–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13226.

Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, Dutriaux C, Maio M, Mortier L, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1412082.

Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Uhara H, Uehara J, Fujimoto M, Takenouchi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in Japanese patients with previously untreated advanced melanoma: a phase II study. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(6):1223–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13241.

Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2521–32. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1503093.

Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival results of a multicentre, randomised, open-label phase 3 study (KEYNOTE-006). Lancet. 2017;390(10105):1853–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31601-X.

Yamazaki N, Takenouchi T, Fujimoto M, Ihn H, Uchi H, Inozume T, et al. Phase 1b study of pembrolizumab (MK-3475; anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) in Japanese patients with advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-041). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2017;79(4):651–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-016-3237-x.

Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and Ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1345–56. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709684.

Hodi FS, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Rutkowski P, Cowey CL, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab alone versus ipilimumab alone in advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067): 4-year outcomes of a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1480–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30700-9.

• Namikawa K, Kiyohara Y, Takenouchi T, Uhara H, Uchi H, Yoshikawa S, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in Japanese patients with advanced melanoma: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre phase II study. Eur J Cancer. 2018;105:114–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.025 This study showed the efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in Japanese patients with advanced melanoma including rare subtypes.

Maio M, Lewis K, Demidov L, Mandala M, Bondarenko I, Ascierto PA, et al. Adjuvant vemurafenib in resected, BRAF(V600) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM8): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(4):510–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30106-2.

Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, Atkinson V, Mandala M, Chiarion-Sileni V, et al. Adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in stage III BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1813–23. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1708539.

Hauschild A, Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Santinami M, Atkinson V, Mandala M et al. Longer follow-up confirms relapse-free survival benefit with adjuvant dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with resected BRAF V600-mutant stage III melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018:JCO1801219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01219.

Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, Dummer R, Wolchok JD, Schmidt H, et al. Adjuvant ipilimumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma (EORTC 18071): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(5):522–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70122-1.

Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, Dummer R, Wolchok JD, Schmidt H, et al. Prolonged survival in stage III melanoma with Ipilimumab adjuvant therapy. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1845–55. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1611299.

Tarhini AA, Lee SJ, Hodi FS, Rao UNM, Cohen GI, Hamid O et al. A phase III randomized study of adjuvant ipilimumab (3 or 10 mg/kg) versus high-dose interferon alfa-2b for resected high-risk melanoma (U.S. Intergroup E1609): preliminary safety and efficacy of the ipilimumab arms. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):9500-. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9500.

Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(19):1824–35. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709030.

Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, Long GV, Atkinson V, Dalle S, et al. Adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo in resected stage III melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(19):1789–801. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1802357.

Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Santinami M, Testori A, Kruit WH, Marsden J, et al. Adjuvant therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2b versus observation alone in resected stage III melanoma: final results of EORTC 18991, a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):117–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61033-8.

Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Testori A, Santinami M, Kruit WH, Marsden J, et al. Long-term results of the randomized phase III trial EORTC 18991 of adjuvant therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2b versus observation in resected stage III melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(31):3810–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.41.3799.

Yamazaki N, Uhara H, Wada H, Matsuda K, Yamamoto K, Shimamoto T, et al. Phase I study of pegylated interferon-alpha-2b as an adjuvant therapy in Japanese patients with malignant melanoma. J Dermatol. 2016;43(10):1146–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1346-8138.13338.

• Namikawa K, Tsutsumida A, Mizutani T, Shibata T, Takenouchi T, Yoshikawa S, et al. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant therapy with locoregional interferon beta versus surgery alone in stage II/III cutaneous melanoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG1309, J-FERON). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47(7):664–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyx063 This article introduced a clinical trial design of the ongoing JCOG1309 (J-FERON) study, which is the first rondomized controlled trial conducted by the Dermatologic Oncology Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG-DOG).

Dummer R, Schadendorf D, Ascierto PA, Arance A, Dutriaux C, Di Giacomo AM, et al. Binimetinib versus dacarbazine in patients with advanced NRAS-mutant melanoma (NEMO): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(4):435–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30180-8.

Weber JS, Gibney G, Sullivan RJ, Sosman JA, Slingluff CL Jr, Lawrence DP, et al. Sequential administration of nivolumab and ipilimumab with a planned switch in patients with advanced melanoma (CheckMate 064): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):943–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30126-7.

Algazi AP, Tsai KK, Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Eroglu Z, Piulats JM, et al. Clinical outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with PD-1 and PD-L1 antibodies. Cancer. 2016;122(21):3344–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30258.

Karydis I, Chan PY, Wheater M, Arriola E, Szlosarek PW, Ottensmeier CH. Clinical activity and safety of pembrolizumab in ipilimumab pre-treated patients with uveal melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(5):e1143997. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402X.2016.1143997.

Kottschade LA, McWilliams RR, Markovic SN, Block MS, Villasboas Bisneto J, Pham AQ, et al. The use of pembrolizumab for the treatment of metastatic uveal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2016;26(3):300–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/CMR.0000000000000242.

van der Kooij MK, Joosse A, Speetjens FM, Hospers GA, Bisschop C, de Groot JW, et al. Anti-PD1 treatment in metastatic uveal melanoma in the Netherlands. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(1):101–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2016.1260773.

Heppt MV, Steeb T, Schlager JG, Rosumeck S, Dressler C, Ruzicka T, et al. Immune checkpoint blockade for unresectable or metastatic uveal melanoma: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2017;60:44–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2017.08.009.

Heppt MV, Heinzerling L, Kahler KC, Forschner A, Kirchberger MC, Loquai C, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes in metastatic uveal melanoma treated with programmed cell death-1 or combined PD-1/cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 inhibition. Eur J Cancer. 2017;82:56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.05.038.

Namikawa K, Takahashi A, Tsutsumida A, Mori T, Motoi N, Jinnai S et al. Nivolumab for patients with metastatic uveal melanoma previously untreated with ipilimumab: a single-institutional retrospective study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:114-.

•• Hayward NK, Wilmott JS, Waddell N, Johansson PA, Field MA, Nones K, et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature. 2017;545(7653):175–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22071 This study demonstrated the whole-genome mutation landscape of acral and mucosal melanoma, which were dominated by stractural variants and different from those previously identified in non-acral cutaneous melanoma.

Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Kuk D, Ott PA, Johnson DB, Tsai KK, et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer. 2016;122(21):3354–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30259.

D'Angelo SP, Larkin J, Sosman JA, Lebbe C, Brady B, Neyns B, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab alone or in combination with Ipilimumab in patients with mucosal melanoma: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(2):226–35. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.67.9258.

Hamid O, Robert C, Ribas A, Hodi FS, Walpole E, Daud A, et al. Antitumour activity of pembrolizumab in advanced mucosal melanoma: a post-hoc analysis of KEYNOTE-001, 002, 006. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(6):670–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0207-6.

Andtbacka RH, Kaufman HL, Collichio F, Amatruda T, Senzer N, Chesney J, et al. Talimogene laherparepvec improves durable response rate in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2780–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.58.3377.

Andtbacka RH, Ross M, Puzanov I, Milhem M, Collichio F, Delman KA, et al. Patterns of clinical response with talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC) in patients with melanoma treated in the OPTiM phase III clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(13):4169–77. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-016-5286-0.

Lian B, Si L, Cui C, Chi Z, Sheng X, Mao L, et al. Phase II randomized trial comparing high-dose IFN-alpha2b with temozolomide plus cisplatin as systemic adjuvant therapy for resected mucosal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(16):4488–98. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0739.

Lian B, Cui C, Song X, Zhang X, Wu D, Si L et al. Phase III randomized, multicenter trial comparing high-dose IFN-a2b with temozolomide plus cisplatin as adjuvant therapy for resected mucosal melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15_suppl):9589-. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.9589.

Kirkwood JM, Strawderman MH, Ernstoff MS, Smith TJ, Borden EC, Blum RH. Interferon alfa-2b adjuvant therapy of high-risk resected cutaneous melanoma: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial EST 1684. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14(1):7–17. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.7.

Kirkwood JM, Manola J, Ibrahim J, Sondak V, Ernstoff MS, Rao U, et al. A pooled analysis of eastern cooperative oncology group and intergroup trials of adjuvant high-dose interferon for melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(5):1670–7.

Mocellin S, Lens MB, Pasquali S, Pilati P, Chiarion SV. Interferon alpha for the adjuvant treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6(6):CD008955. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008955.pub2.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP18ck0106352) and the National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund (29-A-3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Kenjiro Namikawa has received compensation from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Toray Industries, Takara Bio, Eisai, and Pharma International for service as a consultant.

Naoya Yamazaki has received research funding from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Takara Bio, Merck, Amgen, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Sysmex Corporation; and has received compensation from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Takara Bio, Merck, Amgen, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer AG, Pfizer, Merck Serono, Eisai, Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo, Toray Industries, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Teijin Pharma Limited, Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Pharma International for service as a consultant.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Skin Cancer

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Namikawa, K., Yamazaki, N. Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy for Melanoma in Japan. Curr. Treat. Options in Oncol. 20, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-019-0607-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-019-0607-8