Abstract

Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of representative democracy. In recent years, however, elections in many advanced democracies have increasingly come under attack by populist actors and rhetoric questioning the integrity of the electoral process. While scholarly attention has so far largely focused on expert surveys measuring and documenting the objective integrity of different elections, a thorough understanding of citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs and their implications for political behavior is still lacking. Against this background, the present study investigates the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ political behavior in Germany. Specifically, the study aims to assess the influence of electoral-integrity perceptions on turnout, vote choice, and nonelectoral (institutionalized and noninstitutionalized) political participation in the offline and online spheres. The study’s preregistered empirical analysis based on the preelection survey of the 2021 German Longitudinal Election Study shows that electoral-integrity beliefs entail clear implications for citizens’ turnout and vote choice, while their influence on nonelectoral behavior is contingent upon the specific type and sphere of political participation. These findings provide novel insights on the behavioral implications of electoral-integrity beliefs and extend the (scarce) findings of previous research to (1) a broader political action repertoire as well as (2) the German context. The empirical evidence generated comes with far-reaching implications for the general viability of modern democracies, suggesting that the nexus between electoral-integrity beliefs and political behavior can be a “triple penalty” or a “double corrective” for representative democracy.

Zusammenfassung

Freie und faire Wahlen bilden das Herzstück der repräsentativen Demokratie. In den letzten Jahren geraten Wahlen jedoch in vielen entwickelten Demokratien zunehmend unter Beschuss von populistischen Akteur:innen, welche mittels ihrer Rhetorik die Qualität und Integrität des elektoralen Prozesses in Frage stellen. Während sich die wissenschaftliche Debatte bisher weitgehend auf Expert:innenbefragungen zur Messung und Dokumentation der objektiven Integrität verschiedener Wahlen konzentriert hat, so ist über die individuellen Wahrnehmungen elektoraler Integrität seitens der Bevölkerung und insbesondere deren Implikationen für das politische Verhalten der Bürger:innen nur vergleichsweise wenig bekannt. Vor diesem Hintergrund untersucht die vorliegende Studie, welchen Einfluss Wahrnehmungen elektoraler Integrität auf das politische Verhalten der Bürger:innen in Deutschland ausüben. Hierbei fokussiert die Studie auf insgesamt drei verschiedene Formen politischen Verhaltens: die Wahlbeteiligung, die Wahlentscheidung sowie die nichtelektorale (institutionalisierte und nichtinstitutionalisierte) politische Partizipation im Offline- und Online-Bereich. Die präregistrierte empirische Analyse basierend auf der Vorwahlbefragung der German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES) 2021 zeigt, dass elektorale Integritätswahrnehmungen bedeutende Effekte auf die Wahlbeteiligung sowie die Wahlentscheidung haben, während ihr Einfluss auf die nichtelektorale politische Partizipation von der spezifischen Art und dem Bereich der politischen Beteiligung abhängt. Diese Ergebnisse liefern innovative Einsichten bezüglich der verhaltensrelevanten Implikationen elektoraler Integritätswahrnehmungen und erweitern die Befunde bisheriger Forschung um (1) ein breiteres politisches Partizipationsrepertoire sowie (2) den deutschen Kontext. Hinsichtlich der generellen Funktionsfähigkeit moderner Demokratien deutet die in dieser Studie präsentierte empirische Evidenz darauf hin, dass der Zusammenhang zwischen elektoralen Integritätswahrnehmungen und politischem Verhalten als „dreifaches Handicap“ oder „doppeltes Korrektiv“ für die repräsentative Demokratie angesehen werden kann.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of representative democracy. They grant legitimacy to elected governments and strengthen citizens’ support for the political system as a whole (Nohlen 2014, p. 28). In recent years, however, elections in many advanced democracies have increasingly come under attack by populist actors and rhetoric questioning the integrity of the electoral process (Fogarty et al. 2020; Berlinski et al. 2021). Importantly, such accusations have also been raised in countries that have been attested rather high objective levels of electoral integrity, including Germany (Schmitt-Beck and Faas 2021, pp. 140–141, 145). While scholarly attention has so far largely focused on expert surveys measuring and documenting the integrity of different elections (Norris 2013; Norris et al. 2014; van Ham 2015), a thorough and encompassing understanding of citizens’ perceptions and evaluations concerning the correctness and fairness of the electoral process is still lacking.

This shortcoming particularly applies to the study of the behavioral implications of citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs. To date, only very few studies have investigated the relevance of individual electoral-integrity perceptions and evaluations as antecedents of citizens’ political behavior. These studies have focused either on predicting turnout (McCann and Domínguez 1998; Carreras and İrepoğlu 2013; Birch 2010) or voting for incumbent vs. opposition parties (Fumarola 2020). Yet this rather limited focus on turnout and incumbent voting neglects the breadth of citizens’ political action repertoires in modern democracies, including nonelectoral behavior in the shape of institutionalized and noninstitutionalized political participation—both offline and online (Theocharis and van Deth 38,39,a, b).

Against this background, the aim of the present study is to shed light on this blind spot in the scholarly literature by investigating the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ political behavior in Germany. How do citizens react when they feel that elections—as the most central mechanism for making their voices heard in the political process—are rigged? Do they descend into complete political apathy (exit), or do they seek to make themselves heard via different participatory channels (voice)? Specifically, this study aims to assess the impact of electoral-integrity perceptions on turnout, vote choice, and nonelectoral political participation. The following research questions will be addressed: (1) Are citizens who doubt the integrity of the electoral process less likely to participate in elections? (2) If they take part in elections, are they more likely to vote for protest or populist parties or to spoil their vote? (3) Are citizens who perceive the electoral process to be rigged more likely to make use of nonelectoral forms of participation? (4) And do they rely more often on noninstitutionalized channels of participation, such as taking part in protests or sharing political content via social media?

Investigating these questions empirically will provide novel insights on the behavioral implications of electoral-integrity beliefs and extend the (scarce) findings of previous research to (1) a broader political action repertoire as well as (2) the German context. The present study thus follows earlier calls for a more encompassing analysis on the nexus between electoral-integrity beliefs and political behavior (cf. Birch 2010, pp. 1616–1617). The empirical evidence generated by this study comes with far-reaching implications for the general viability of modern democracies: Ultimately, if it turns out that doubts about the integrity of elections induce citizens to stay home on election day or to withdraw completely from participating in the political process, both the functioning and legitimacy of democratic systems will be severely hampered.

The study’s preregistered empirical analysis is based on newly collected data from the preelection survey of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES, 2022), which was conducted in the weeks shortly before the 2021 German Federal Election. The survey contains a wide variety of items measuring citizens’ views about the integrity of the electoral process as well as their electoral and nonelectoral participation, rendering it an ideal source for expanding our knowledge on the nexus between electoral-integrity beliefs and political behavior more generally.

The remainder of this study is structured as follows. Section 2 clarifies the study’s core concepts, specifies its main theoretical arguments, and derives testable hypotheses on the relationship between electoral-integrity beliefs and different forms of political participation. Section 3 discusses the data, operationalizations, and methods used in the empirical part of the study. Section 4 presents the findings of the empirical analyses. Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the study’s main insights and their broader implications, as well as possible avenues for future research.

2 Theory and Hypotheses

In democratic political systems, free and fair elections perform an important legitimizing function: They not only bestow legitimacy on governments that emanate from a competitive electoral process, but they also elicit citizens’ beliefs in the legitimacy of the political system as a whole (Nohlen 2014, p. 28). From this perspective, doubts about the integrity of elections on the part of the citizens may operate in the same way as a canary in a coal mine, sending early-on signals that citizens are dissatisfied with how the electoral system and process work and that the legitimacy of the political system itself is at stake.

Despite the centrality of free and fair elections for the general viability of representative democracies, scholarly concern about the integrity of elections and about citizens’ views on the fairness and correctness of the electoral process is only a rather recent phenomenon. At least in established democracies, it seems, electoral integrity has long been taken for granted, rendering detailed scientific inquiries into the topic less expedient (Birch 2008, pp. 306–307). In the meantime, questions of electoral integrity have become a topic of debate also within longstanding democracies, for at least two reasons: First, instances of electoral malpractices have been documented even among established democracies, including Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Norris 2013, p. 563; Karp et al. 2018, p. 11). Second, matters of electoral integrity have been discovered as a prime theme by populist parties and actors in order to discredit political opponents and the legitimacy of democratic decisions and outcomes. While Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated assertions about voter fraud in the context of the “stolen” 2020 US presidential election are a case in point (Berlinski et al. 2021, p. 1), similar strategies and accusations can also be found in other established democracies. For example, during the campaign for the 2021 German Federal Election, the populist right-wing party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) regularly portrayed postal voting as a direct pathway to vote rigging (ZDF 2021), despite the fact that German elections have been attested to be among the cleanest worldwide (Norris et al. 2014, p. 794; Norris 2019, p. 10). It seems likely that such rhetoric will leave its marks on (certain) citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs (Schmitt-Beck and Faas 2021, p. 145).

Overall, these developments underline that matters of electoral integrity establish a cause for concern even among established democracies. What is more, they clarify why a detailed analysis of the behavioral implications of citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs may provide us with important insights concerning the long-term functioning of modern democracies: If citizens’ beliefs about the conduct of elections convey signals about the legitimacy of a political system (cf. Birch 2010, p. 1602), these signals will become visible and unfold their politically tangible effects via citizens’ political behavior. Therefore, it is essential to analyze in which ways the (perceived) integrity of elections is connected to citizens’ political behavior and whether citizens’ political participation differs depending on whether they see elections in their country as free and fair.

2.1 Conceptual Framework

Before turning to these questions, let us clarify the conceptual underpinnings and meaning of this study’s core concepts, electoral integrity and political participation.

2.1.1 (Perceptions of) Electoral Integrity

While everyday language may provide us with an intuition about what “free and fair” elections imply, this intuition may vary across individuals and contexts and cover different aspects related to the proper conduct of elections. Norris (2013, 2014) has proposed a general conceptualization and definition, according to which electoral integrity pertains to “universal standards about elections reflecting global norms applying to all countries worldwide throughout the electoral cycle, including during the pre-electoral period, the campaign, on polling day, and its aftermath” (Norris 2014, p. 21). As Norris et al. (2014, p. 790) emphasize, when evaluating the integrity of elections, “[a]ttention often focuses on the finish line, but like a marathon, elections may be won or lost at the starting gate.” For the study of electoral integrity and citizens’ beliefs about the proper conduct of elections, it is therefore imperative to consider assessments at different stages of the electoral cycle and the universal standards they comprise. Among others, such standards encompass impartial electoral laws; equal opportunities for parties and candidates to run for office; possibilities for eligible voters to vote securely by mail, the internet, or from abroad; and overall fair and impartial electoral authorities (for a complete overview, see Norris 2013, p. 567; Norris and Grömping 2019, p. 29). Ultimately, the integrity of a given election can be assessed by evaluating the fulfillment or violation of these universal standards concerning the proper conduct of democratic elections (van Ham 2015, pp. 716–719).

In this connection, a crucial question relates to the source of such electoral-integrity assessments, i.e., who evaluates the fulfillment or violation of the aforementioned standards. Here, we may distinguish between (more or less) objective evaluations, such as those issued by independent election observers (Hyde 2011) or as gathered through expert surveys (Norris et al. 2014), and ordinary citizens’ subjective perceptions and beliefs about the integrity of elections. This distinction matters, as citizens’ perceptions about the integrity of elections do not necessarily have to correspond with the objective quality thereof (Bowler et al. 2015, p. 8; Schmitt-Beck and Faas 2021, pp. 141, 156). In this study, the focus is on ordinary citizens’ perceptions rather than objective assessments of the integrity of elections, with the underlying premise that it is first and foremost individual perceptions of electoral integrity that provide citizens with relevant signals and cues for whether and how to become active politically and which specific options from the political action repertoire to choose from (cf. Carreras and İrepoğlu 2013, p. 611).Footnote 1

2.1.2 Political Participation

In general terms, political participation pertains to “citizens’ activities affecting politics” (van Deth 2014, p. 351). As such, it focuses on voluntary activities by ordinary people in their role as citizens, with the intention to affect political outcomes or to express political aims (cf. Teorell et al. 2007, p. 336; van Deth 2014, pp. 354–360). Following this basic conceptualization, a wide variety of activities qualify as political participation. The universe of all these activities has been depicted as the “repertoire of political participation” (van Deth 2003, 2014). Throughout the last decades, this repertoire has grown steadily, with the activities used by citizens to affect politics or to express political aims becoming more and more diverse. Accordingly, nowadays the repertoire of political participation contains genuinely political activities alongside “non-political activities used for political purposes” (van Deth 2014, p. 350). What is more, with the spread of internet-based technologies, citizens’ political activities can be conducted both in the offline and online realms, further expanding citizens’ opportunities to voice their concerns and affect politics by contacting politicians via email, by signing online petitions, or by sharing political contents via social media (Theocharis and van Deth 38,39,a, b).

For the empirical analysis of political participation, the various activities that make up the political participation repertoire are usually summarized into distinct “types” or “modes” that share common characteristics and features (see van Deth 2014, p. 361; Schnaudt and Weinhardt 2018, pp. 312–313). In this study, a first relevant distinction refers to the difference between electoral and nonelectoral political participation. Electoral participation refers to citizens’ participation in elections (turnout) as well as the specific choices they opt for on election day (vote choice). Nonelectoral participation, in contrast, comprises any remaining political activities that citizens may choose to affect politics or to express political aims. Here, we rely on a second, widely employed distinction between institutionalized and noninstitutionalized political participation (Fuchs and Klingemann 1995). Institutionalized participation concerns citizens’ political activities that take place within the confines of a political system’s institutional structure and that are directly related to the institutional process and the institutions and authorities governing this process.Footnote 2 Noninstitutionalized participation, in contrast, is located outside the confines of the institutional structure and not (directly) geared toward the institutions and authorities running the institutional process (cf. Hooghe and Marien 2013, pp. 133–134; Schnaudt 2019, p. 240). Following these refinements, institutionalized forms of political participation include activities such as contacting politicians and working or campaigning for political parties, whereas noninstitutionalized forms comprise activities such as protesting, signing petitions, and engaging in political consumerism (Teorell et al. 2007, p. 341; Hooghe and Marien 2013, pp. 133–134). Finally, a third and last conceptual distinction pertains to the sphere in which political activities take place. Here, both institutionalized and noninstitutionalized forms of participation may be conducted offline and online (Theocharis and van Deth 2018a, ch. 5, 2018b).

To summarize, the present study will assess the impact of individual citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs on various forms and types of political participation, including (1) turnout, (2) vote choice, and (3) institutionalized and (4) noninstitutionalized participation in both the offline and online realms. This strategy allows us to analyze and detect possibly varying effects of electoral-integrity beliefs on different forms and types of political participation, providing new insights on the nexus between electoral integrity and political behavior.

2.2 Electoral-Integrity Beliefs and Political Participation

Previous studies investigating citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs have primarily focused on identifying their antecedents, trying to explain why certain citizens are more (or less) likely than others to doubt the integrity of elections (see, inter alia, Birch 2008; McAllister and White 2011; Schmitt-Beck and Faas 2021). In contrast, scholarly attention to the consequences of individual electoral-integrity beliefs, and in particular their behavioral implications, has remained relatively scarce (Norris 2018, p. 223). Of the few studies that analyze the behavioral consequences of electoral-integrity beliefs, almost all are characterized by a limited scope regarding the breadth of citizens’ political action repertoire, looking at turnout or incumbent vs. opposition voting only (McCann and Domínguez 1998; Birch 2010; Carreras and İrepoğlu 2013; Fumarola 2020). Against this background, Birch’s (2010, p. 1616) observation from more than a decade ago stating that “similar analyses could profitably be extended to a range of aspects of political behavior, including vote choice and other forms of political participation” is more topical than ever. Below, we follow her invitation for an extended and more encompassing analysis by considering the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on various forms of political participation.

2.2.1 Turnout

When it comes to the underlying reasons and motivations for participating in elections, previous research has identified an embarrassment of riches (Smets and van Ham 2013). One of the most established arguments states that citizens’ decisions to partake in an election depend on their political efficacy, i.e., whether they feel their vote is counted and can make a difference with regard to the outcome of an election (e.g., Verba et al. 1995, pp. 346, 358). For citizens’ votes to matter in this way, elections need to exhibit certain qualities. In that regard, a crucial and defining characteristic of democratic contests is the indeterminacy of electoral outcomes prior to election day. To guarantee such indeterminacy, appropriate procedures must be in place that preserve and maintain the democratic character of elections as free and fair. In other words, “procedural certainty is a necessary requirement for the uncertainty in outcomes that defines democracy” (Birch 2010, p. 1603). “In elections where contests are procedurally fair, citizens can be confident that their ballots will count and that candidates and parties compete on a level playing field. When it is widely believed that systematic fraud or abuse depresses competition, however, the outcome may be regarded as foregone conclusion” (Norris 2014, p. 133). Accordingly, if citizens feel that the electoral process is fair and the outcome of elections not determined before casting a vote, they are likely to consider their participation in elections as a meaningful and worthwhile democratic activity, with a tangible chance of influencing the final outcome. Conversely, “[w]hen citizens perceive that elections are unfair, they may prefer to stay at home on election day because they believe that their vote will have no impact on the electoral results and on the direction of public policies” (Carreras and İrepoğlu 2013, p. 611). Put differently, they are likely to use the “exit” option by not participating at all.

Following these assertions, we may expect citizens who doubt the integrity of elections to be less likely to turn out on election day. This proposition has received first empirical support in previous studies. In their study analyzing the impact of perceived electoral fraud on citizens’ propensity to vote, McCann and Domínguez (1998, p. 495) found that citizens who perceived electoral malpractices to be widespread were indeed less likely to take part in elections. This finding was corroborated in the studies by Birch (2010, p. 1610) and Carreras and İrepoğlu (2013, p. 615), who showed that citizens who perceived elections to be conducted fairly were more likely to vote. Finally, the cross-national findings by Norris (2014, p. 140) indicate that “those with greater faith in the honesty and fairness of the voting process proved more willing to cast a ballot.”

Based on these theoretical and empirical insights, a first hypothesis concerning the influence of citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs on participation in elections reads as follows:

H1a

The more negative citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity, the less likely citizens are to vote.

Whereas this first hypothesis follows from a perspective that focuses on citizens’ (perceived) chances of having a tangible impact on the election outcome, it neglects other motives for turning out. Rather than using the “exit” option by abstaining from an election, citizens who doubt the integrity of elections may turn out to vote to “voice” their concerns about the electoral process and to vent their dissatisfaction with how the electoral system works. As Booth and Seligson (2009, p. 148) ask, why “would highly disaffected citizens of a democracy become inert or drop out of the political arena? … [A]t least some disgruntled citizens, rather than doing nothing at all, might work for change within the system or strive to change the system.” While such striving for change will manifest itself first and foremost in the specific vote choices that citizens opt for (see Sect. 2.2.2), the general idea that negative electoral-integrity beliefs might also induce citizens to become politically active indicates that the assumption of simple linear effects of electoral-integrity beliefs on turnout (H1a) might be too shortsighted. Rather, it can be expected that both citizens exhibiting positive and negative perceptions of electoral integrity are motivated to vote, albeit for different reasons: Those who perceive elections as free and fair will turn out because they feel that the political system is responsive to their demands and that their vote will make a difference, and those who doubt the integrity of elections will turn out to voice their criticism and signal their desire for improving the electoral system and process. Accordingly, the nexus between electoral-integrity beliefs and turnout can be expected to be U‑shaped, with citizens who exhibit more positive and more negative electoral-integrity beliefs being more likely to vote than those with intermediate perceptions of electoral integrity (cf. Booth and Seligson 2005, p. 541, 2009, p. 22).

Empirical tests of these arguments are scarce and have been applied only to the relationship between political support and political participation, with mixed findings for Latin America (Booth and Seligson 2005, 2009) and Europe (Schnaudt 2019, pp. 256–258). Therefore, this study breaks new ground by testing the following hypothesis:

H1b

The relationship between electoral-integrity beliefs and turnout is U‑shaped, with citizens who exhibit more negative and more positive electoral-integrity perceptions being more likely to vote than citizens with intermediate integrity perceptions.

2.2.2 Vote Choice

Next to influencing citizens’ general propensity to participate in elections, electoral-integrity beliefs may exert an impact on the specific choices citizens make at the ballot box. As argued above, if citizens who feel that elections are rigged decide to turn out to vote nonetheless, they are likely to choose an option that signals their dissatisfaction with and desire for changing the electoral process. In essence, such vote choices resemble protest votes, i.e., votes that are driven less by policy concerns but are primarily cast to galvanize (incumbent) political elites (van der Brug and Fennema 2003, p. 58). A first form of such voting may assume the shape of “electoral integrity performance voting” through which citizens punish incumbent governments for perceived violations of electoral integrity by opting for (mainstream) opposition parties instead (Fumarola 2020, p. 45). A second form of “insurgent protest voting” implies casting a ballot for antiestablishment or populist parties rather than opting for established political parties and candidates that citizens associate with (unwanted) status quo politics (Alvarez et al. 2018, p. 138). A third form of protest voting involves casting blank, null, or spoiled votes (“BNS protest voting”) and is used if citizens see no viable party alternative to voice their dissatisfaction (Alvarez et al. 2018, pp. 144–147). Following these insights, citizens who doubt the integrity of elections may opt to voice their concerns by voting for mainstream opposition parties, voting for antiestablishment or populist parties, or casting invalid ballots, rather than using the exit option by not turning out at all.

From a demand-side perspective, research on procedural justice provides evidence that fair procedures matter for citizens’ assessments of political institutions and authorities (Tyler 2006; Schnaudt et al. 2021). It thus seems likely that citizens will hold political parties accountable for perceived electoral malpractices in their country and that they will primarily blame incumbent governments, as governmental ministries and agencies are usually responsible for the organization and management of elections (Fumarola 2020, pp. 44–45). In making a deliberate choice against incumbent parties and candidates at the ballot box and voting for opposition or populist parties or spoiling their vote instead, citizens may see one way to voice their opposition toward the perceived deficiencies in the electoral process, aiming to improve the status quo in the long run.

An increased propensity for anti-incumbent and protest voting among those who doubt the integrity of elections can also be substantiated when looking at supply-side arguments. As outlined earlier, questions pertaining to electoral integrity are a prominent feature in the political discourse of populist parties. In line with an understanding of populism “that considers society to be ultimately separated into […] ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde 2004, p. 538, emphasis original), populist parties and actors rely on an anti-elitist rhetoric that actively portrays elections as rigged or “stolen,” with the overarching aim of discrediting established political parties and challenging the legitimacy of democratic decisions and outcomes “in the name of the people” (cf. Fogarty et al. 2020; Schmitt-Beck and Faas 2021; ZDF 2021). Such rhetoric resonates well with—and is likely to reinforce—existing doubts about the proper conduct of elections among (certain segments of) the citizenry. When it comes to making a specific vote choice, citizens who already exhibit doubts about the proper conduct of elections are thus likely to vote for parties and candidates whose political supply corresponds with citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs. For the German case under consideration in this study, this will be first and foremost the AfD (cf. Schmitt-Beck and Faas 2021, p. 145; ZDF 2021).

In light of the preceding discussion, the following three hypotheses concerning the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on vote choice will be tested:

H2a

The more negative citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity, the more likely citizens are to vote for mainstream opposition rather than incumbent parties.

H2b

The more negative citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity, the more likely citizens are to vote for populist (i.e., the AfD) rather than incumbent parties.

H2c

The more negative citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity, the more likely citizens are to cast invalid ballots rather than vote for incumbent parties.

2.2.3 Nonelectoral Political Participation

If citizens feel that elections are rigged and therefore not a viable instrument for affecting political outcomes, they may (also) turn to nonelectoral channels of participation. Concerning the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ institutionalized and noninstitutionalized participation in the offline and online realms, we contend that negative perceptions of electoral integrity will encourage citizens’ engagement in noninstitutionalized political activities, while undermining their institutionalized participation (see also Norris 2014, pp. 136–137). As argued earlier, citizens’ perceptions about the integrity of elections provide them with cues and signals regarding the general responsiveness and legitimacy of political institutions and authorities (Birch 2010, p. 1602). If citizens believe that the political system and its institutions and authorities cannot be trusted with regard to the proper organization and conduct of free and fair elections, it seems unlikely that they will switch to other institutionalized modes of participation that are targeted at and governed by the very same institutions and authorities. Quite the contrary: Citizens’ doubts about the integrity of elections may instead prompt them to voice their dissatisfaction and concerns via noninstitutionalized modes of participation that are located outside the confines of the political system’s institutional structure and that try to circumvent the institutions and authorities that citizens lack confidence in (Hooghe and Marien 2013, p. 132; Schnaudt 2019, p. 241).

A so far unresolved question concerns the influence of electoral-integrity beliefs on offline and online forms of institutionalized and noninstitutionalized participation. In this connection, the existing literature does not offer any hints on whether to expect any systematic differences between the offline and online realms. However, following our preceding arguments, the decisive distinction concerning the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs seems to be based more strongly on the type rather than the sphere of nonelectoral participation. This distinction pertains to the question of whether participation takes place within or outside the confines of the institutional structure and whether it is geared toward or tries to circumvent the institutional process and the institutions and authorities governing it. Therefore, it appears plausible to expect that the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on nonelectoral participation will differ between institutionalized and noninstitutionalized activities but not between offline and online modes of the same type of participation.

Empirical tests of the abovementioned propositions are virtually nonexistent. Only the study by Norris (2014) has provided tentative evidence on a single aspect, indicating that citizens who feel that electoral malpractices are widespread are indeed more likely to engage in protest activism, whereas citizens who perceive elections to be fair are less likely to do so (Norris 2014, p. 142). While there is thus first empirical evidence concerning the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on protest activism as one form of noninstitutionalized participation, an encompassing empirical analysis covering institutionalized and noninstitutionalized nonelectoral behavior in the offline and online realms is still lacking. To shed light on these aspects, the following hypotheses will be tested in the empirical part of this study:

H3a

The more negative citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity, the less likely citizens are to make use of institutionalized political participation (both offline and online).

H3b

The more negative citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity, the more likely citizens are to make use of noninstitutionalized political participation (both offline and online).

Both of the preceding hypotheses rest on the assumption that electoral-integrity beliefs exert linear effects on nonelectoral participation. However, as our earlier discussion concerning voter turnout has brought to light, this assumption may be misguided. First, there is no reason to believe that citizens who consider elections as free and fair, and who therefore may hold benevolent views regarding the political system’s general responsiveness, will restrict themselves to institutionalized channels of participation only. Exactly because they believe in the responsiveness and legitimacy of the political system, they are likely to make use of the whole political action repertoire to affect political outcomes and express their political aims. “While seeking influence through voting is not an every-day option and party activity might be rather time-consuming for effecting change, non-institutionalized activities such as signing petitions, protesting, or boycotting might be viable alternatives for achieving specific political goals or expressing one’s political opinions” (Schnaudt 2019, p. 241). Second, there are good arguments for why citizens who consider elections as rigged may rely on institutionalized forms of participation. Considering our discussion regarding vote choice, citizens can be expected to attribute responsibility for electoral malpractices primarily to incumbent political parties and candidates. Accordingly, citizens who doubt the integrity of elections might still opt to contact politicians from opposition or protest parties or start to work for these parties themselves in order to voice their discontent with the electoral process and to affect political outcomes “from within” (Booth and Seligson 2009, pp. 148–149; Schnaudt 2019, p. 242). Following these arguments, we may expect a U-shaped relationship between electoral-integrity beliefs and nonelectoral participation: While both citizens with positive and negative perceptions of electoral integrity will experience an impetus for using institutionalized and noninstitutionalized participation, citizens with intermediate integrity perceptions will be less inclined to become politically active. We test this proposition with the following hypothesis:

H3c

The relationship between electoral-integrity beliefs and (non)institutionalized participation (both offline and online) is U‑shaped, with citizens who exhibit more negative and more positive electoral-integrity perceptions being more likely to make use of (non)institutionalized participation than citizens with intermediate integrity perceptions.

3 Data, Operationalization, and Methods

The empirical test of the hypotheses specified in the preceding section is based on a preregistered analysis plan that was compiled prior to the release of and access to the data used in this study.Footnote 3

The analysis plan gives an overview pertaining to all steps of this study’s empirical analysis and adds further details to the illustrations below.

3.1 Data

The empirical analysis is based on the preelection survey of the German Longitudinal Election Study (GLES, 2022), which was conducted within the four weeks prior to the 2021 German Federal Elections. The GLES preelection survey is a cross-sectional survey using a mixed-mode design consisting of online interviews (CAWI) as well as paper-and-pencil interviews (for a recent assessment of mixed-mode surveys, see Wolf et al. 2021). The target population of the survey comprises German citizens with a minimum age of 16, living in private households in Germany at the time of the survey. The survey is based on a high-quality register sample with oversampling for the eastern German population and comprises a sample size of 5116 respondents.

3.2 Operationalization

The main concepts and variables of interest for this study are perceptions of electoral integrity, turnout and vote choice, and institutionalized and noninstitutionalized nonelectoral participation in the offline and online realm. The 2021 preelection survey of the GLES contains suitable items to operationalize each of these concepts.

3.2.1 Electoral-Integrity Beliefs

The study’s main independent variable, electoral integrity beliefs, will be operationalized via three items measuring citizens’ perceptions concerning the proper conduct of elections in Germany (q12a–c). On a five-point scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” citizens are invited to evaluate the following three statements: (1) “All parties in the federal election campaign have a fair chance to present their positions to eligible voters”; (2) “Federal elections are conducted correctly and fairly by the relevant authorities”; and (3) “Voting by absentee ballot is a secure procedure.” In line with our conceptual discussion pertaining to different stages and periods in the electoral cycle, these items refer to different aspects of the electoral process, allowing for a more encompassing and reliable measurement of citizens’ electoral integrity beliefs than the single-item measurement used in some previous studies (cf. Birch 2010, p. 1608).

For the empirical analysis, the three items are combined into a single scale measuring citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs. The unidimensionality of the scale was assessed and validated via exploratory factor analysis, yielding a single factor accounting for 69% of the variance in the three original items. This finding corresponds with previous studies indicating that citizens’ perceptions pertaining to the integrity of different aspects of the electoral process tend to go hand in hand (cf. Norris 2019, p. 11; Fumarola 2020, pp. 49–50), rendering a single scale an efficient and more reliable operationalization of electoral-integrity beliefs. For the construction of the final scale, the three items were recoded to range from 0 to 4 and subsequently combined into an additive scale ranging from 0 to 12 (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.76). In line with the specification of the hypotheses, higher values on the scale indicate more negative perceptions of electoral integrity. Overall, citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity in Germany are very positive: Only 10% of respondents exhibited a value of 6 or higher on the 0–12 scale (see Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material).

3.2.2 Political Participation

Overall, this study’s empirical analysis will consider six different dependent variables capturing different forms and types of political participation. Turnout is operationalized via an item measuring citizens’ intention to vote in the 2021 German Federal Election (q6). Citizens could choose between five options: “certain to vote,” “likely to vote,” “might vote,” “not likely to vote,” and “certain not to vote.” In addition, there is a further item using the same response options that asks respondents who are too young to vote about the hypothetical likelihood of taking part in the elections (q7). For the operationalization of turnout, we relied on a dummy-coded variable constructed from both items that captures respondents who are certain or likely to vote (value 1) and those who are still uncertain or likely/certain not to vote (value 0). Those respondents indicating that they already voted via postal ballot were given a value of 1. In total, a substantial 96% of respondents in the GLES preelection survey are classified as (likely) voters.

Vote choice establishes the second dependent variable and is operationalized by a combination of three items measuring citizens’ (intended) vote choice for the party vote (Zweitstimme) in the 2021 German Federal Election (q8b, q9b, q10b). The first item asks citizens who are eligible to vote about their intended vote choice at the election, while the second asks those who are too young to vote about their hypothetical vote choice.Footnote 4 In addition, the third item asks those who already voted by postal ballot to indicate the party they effectively voted for. When answering, citizens could choose from the following options: CDU/CSU, SPD, AfD, FDP, Die Linke, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, or “other.” What is more, citizens could indicate that they would cast an invalid vote. The final operationalization of vote choice combines the answers to all three items into a single variable. In line with the formulation of our hypotheses (see H2a–c), the answer options were recoded as follows: “incumbent parties” (comprising intended vote choice for CDU/CSU and SPD), “opposition parties” (comprising intended vote choice for FDP, Die Linke, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, or “other”), “populist parties” (comprising intended vote choice for AfD), and “invalid vote.” By looking at opposition parties and the AfD separately—rather than combining and investigating opposition parties as a whole—this operationalization allows for an efficient test of hypotheses 2a–c in a single analysis step. Overall, 48% of respondents are classified as incumbent voters, 44% as opposition voters, 7% as populist voters, and 1% as invalid voters.

Nonelectoral participation, as the third dependent variable in this study, is operationalized via four separate measures reflecting offline and online institutionalized participation as well as offline and online noninstitutionalized participation. The GLES preelection survey contains two item batteries asking citizens about their political participation in the offline (q73a–h) and online (q72a–h) realms. For each item battery, citizens could indicate whether they had done any of the eight political activities listed within the previous 12 months. Unfortunately, the list of activities is rather unbalanced, containing more noninstitutionalized forms of participation than institutionalized ones. For offline institutionalized participation, we relied on a dummy-coded variable capturing whether citizens had “donated to a political party or organization” or “supported the election campaign of a political party.” Ten percent of respondents reported to have done so. For online institutionalized participation, we made use of a dummy-coded variable indicating whether citizens had “used government-provided citizen participation platforms on the internet” or “contacted politicians via the internet.” Here, roughly 6% of respondents mentioned having done so. For offline noninstitutionalized participation, we constructed a dummy-coded variable reflecting whether citizens took part in a community action group, demonstrated, collected signatures, boycotted products for political reasons, or wrote a letter to an editor on political issues (38% of respondents). Lastly, for operationalizing online noninstitutionalized participation, a dummy-coded variable was employed that captures whether citizens expressed, shared, or liked political views on social media; wrote comments on political issues in online portals or political articles on online blogs; or took part in online petitions (41% of respondents).

3.2.3 Controls

To assess the robustness and relative importance of electoral-integrity beliefs as antecedents of various forms of political participation, as well as to control for any spurious effects, the empirical analysis includes several control variables. To keep the results of our empirical analysis largely comparable to existing findings, the selection of controls was informed by previous studies (cf. Birch 2010, p. 1613; Norris 2014, p. 140). On the hand, we controlled for socioeconomic background variables, including age, gender, education, employment status, and evaluations of one’s personal economic situation. On the other hand, we controlled for a set of attitudinal factors that are related to both electoral-integrity beliefs and political participation. These include political interest, political efficacy, and satisfaction with democracy, as well as social trust.Footnote 5

3.3 Methods

In general, this study follows a factor-centric design (cf. Gschwend and Schimmelfennig 2007) that is primarily interested in the specific effects of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ political participation. Overall, our empirical analysis considers a total of six dependent variables, capturing a broad variety of citizens’ political activities. Five of these dependent variables exhibit a binary nature (those referring to turnout and nonelectoral participation), rendering binary logistic regression the optimal choice for conducting the empirical analysis. For vote choice, the dependent variable is categorial, making multinomial logistic regression our statistical method of choice. For the test of curvilinear effects (H1b and H3c), an additional squared term for electoral-integrity beliefs is included in the models. The empirical tests for each of the several hypotheses specified follow a two-step approach, considering both bivariate and multivariate assessments. In all statistical models, all continuous independent variables are normalized to range between 0 and 1.

Considering that this study relies on cross-sectional data, a final note of caution with regard to this study’s empirical analysis concerns possible issues of endogeneity. As Fumarola (2020, p. 45) elaborates, “[t]he direction of the relationship between individual evaluations/perceptions and voting behaviour is still disputed. Regarding the present study, it might be claimed that the relationship between the main independent and the dependent variables is ‘the other way around’: that is, that electoral preferences influence and structure perceptions of electoral integrity” (see also Norris 2014, p. 136). While such problems cannot be completely resolved with the cross-sectional data at hand, they are at least alleviated in the present study: First, the data used here were collected in a preelection survey shortly before the 2021 German Federal Elections. This makes it less likely that any positive or negative experiences from (not) voting in the last election in 2017 were still a valid concern when answering questions about electoral integrity in 2021. Second, the use of prospective vote intention and intended vote choice rather than reported voting behavior and vote choice from the preceding election (see Birch 2010, p. 1607) underlines the presumed order of electoral-integrity beliefs and political participation in the causal chain, with perceptions about electoral integrity influencing citizens’ future decisions to become politically active. Third and last, while arguments regarding endogeneity problems may be plausibly raised with regard to electoral behavior, it is less evident how they could apply to nonelectoral participation. For example, it is far from obvious how boycotting products for political reasons could induce citizens to develop positive or negative views and perceptions about the integrity of elections in their country. In summary, then, while questions of causality cannot be conclusively tackled and resolved with the data at hand, this study is well suited to make an innovative contribution by expanding our knowledge on the nexus between electoral-integrity beliefs and political behavior more generally.

4 Analysis

4.1 Turnout

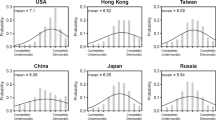

We start our empirical examination by investigating the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on voter turnout. Figure 1 presents the results from a series of binary logistic regression models pertaining to the test of H1a (panel A) and H1b (panel B).

As evident in panel A, perceptions of electoral integrity exert a negative and statistically significant effect on voter turnout in both the bivariate and multivariate models. In line with H1a, this implies that citizens exhibiting more negative perceptions of electoral integrity were less likely to turn out in the German Federal Election 2021. Substantively, the bivariate results imply that a person with most positive perceptions of electoral integrity has a 97%probability of voting. This probability decreases to 83% for a person with most negative perceptions—a notable difference of 14 percentage points. In the multivariate case, holding all other covariates at their observed values, the difference in predicted probabilities between those with most positive and most negative perceptions of electoral integrity still amounts to four percentage points (97% vs. 93%).Footnote 6 The fact that these effects and differences prevail even under control of other potent predictors of voter turnout, such as political interest, efficacy, and economic evaluations, underlines the substantive importance of electoral-integrity beliefs for voter turnout and lends support to the theoretical expectation formulated in H1a.

Turning to panel B, we inspect the presence of U‑shaped effects of electoral-integrity beliefs on turnout. In both the bivariate and multivariate models, the signs for the linear terms of electoral-integrity perceptions are negative, whereas the squared terms are positive. This pattern of coefficients supports the notion of a U-shaped relationship, with the effect of electoral-integrity perceptions first being negative and then turning positive the further we move from positive toward negative perceptions. To illustrate this finding, let us consider the predicted probabilities of voting based on the bivariate model: A person with most positive perceptions of electoral integrity (value 0 on the 0–12 scale) has a 98% probability of voting. This probability decreases to 91% for persons with intermediate perceptions (value 8) and then increases to 94% for persons with most negative perceptions of electoral integrity (value 12). While the observed pattern is similar in the multivariate model, the effects are less pronounced and do not reach statistical significance.Footnote 7 Accordingly, a U-shaped relationship between electoral-integrity beliefs and turnout as stated in H1b finds support in a bivariate analysis but does not stand up to empirical scrutiny in a multivariate setting.Footnote 8

4.2 Vote Choice

In the second step of our empirical analysis, we investigate the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ vote choice (H2a–c). Figure 2 presents the results from bivariate and multivariate multinomial regression models, using voting for incumbent parties as the reference category.

Panel A considers the contrast between voting for incumbent vs. opposition parties (H2a). In both the bivariate and multivariate models, the coefficient for electoral-integrity perceptions is positive and statistically significant, indicating that citizens with more negative perceptions of electoral integrity are more likely to vote for opposition than incumbent parties.Footnote 9 In panel B, the same observation is evident for the contrast between incumbent vs. populist voting (H2b). Citizens exhibiting more negative views concerning the proper conduct of elections are more likely to vote for populist than incumbent parties. Lastly, panel C looks at the contrast between voting for incumbent parties vs. casting an invalid ballot (H2c). Here again it is evident that, with more negative perceptions of electoral integrity, citizens exhibit a higher likelihood of invalid voting than of voting for incumbent parties.Footnote 10

Overall, these results lend support to the theoretical expectations formulated in H2a–c. What is more, they highlight that negative perceptions of electoral integrity among citizens come with a clear and consistent penalty for incumbent parties on election day. While the predicted probability of voting for incumbent parties is 53% among citizens with most positive perceptions of electoral integrity, this probability shrinks to 24% among citizens with most negative perceptions. By contrast, the respective probability to vote for opposition parties, to vote for populist parties, or to cast invalid ballots increases by 7, 22, and 2 percentage points as one moves from citizens with the most positive to the most negative electoral-integrity perceptions (holding all covariates at their observed values).Footnote 11 Accordingly, doubts about the proper conduct of elections among the population primarily hurt incumbent parties, and they primarily benefit populist parties. This conclusion is substantiated in further, nonregistered exploratory analyses showing that while citizens with more negative perceptions of electoral integrity prefer abstaining over voting for incumbent or opposition parties, they prefer voting for populist parties over staying at home on election day (see Table E2 and Fig. E2 in the Supplementary Material). Evidently, the ability to mobilize citizens who feel that elections are rigged establishes a distinctive characteristic of populist parties (here, the AfD) that distinguishes them from any other political opponent.

4.3 Nonelectoral Political Participation

In the final step of our analysis, we turn to the impact of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ institutionalized and noninstitutionalized participation in the offline and online realms. Figure 3 shows the results from a series of bivariate and multivariate binary logistic regression models pertaining to the test of H3a and H3b.

A cursory glance at the effects of electoral-integrity perceptions across panels A–D indicates that these do not matter (much) for citizens’ nonelectoral behavior. Most of the coefficients for electoral-integrity perceptions do not reach statistical significance, and in particular, the results from the multivariate models indicate that beliefs about the proper conduct of elections cannot be considered important drivers of citizens’ nonelectoral behavior. More specifically, panels A and B show that more negative perceptions of electoral integrity are not associated with a decrease in citizens’ likelihood to engage in institutionalized forms of participation. These findings hold for both offline and online activities and thus contradict H3a. Regarding noninstitutionalized participation, the picture is more variegated. While perceptions of electoral integrity are unrelated to noninstitutionalized forms of participation in the offline realm (panel C), more negative perceptions concerning the conduct of elections imply a higher likelihood to engage in online forms of noninstitutionalized participation (panel D). This effect is substantial: The probability to participate in noninstitutionalized online activities is 16 percentage points higher for a person with most negative perceptions of electoral integrity as compared to a person with most positive perceptions (54% vs. 38%), holding all other model covariates at their observed values.Footnote 12 In light of these findings, H3b receives support for online forms of noninstitutionalized participation only.

Lastly, we consider the presence of a U-shaped relationship between electoral-integrity perceptions and nonelectoral behavior as stated in H3c. For the empirical test of this hypothesis, we added an additional squared term for electoral-integrity perceptions to the models presented in Fig. 3. The findings of this additional analysis are straightforward: U‑shaped effects of electoral-integrity perceptions were not found for any of the four types of nonelectoral political participation (i.e., none of the squared terms is statistically significant).Footnote 13 Therefore, the current study does not provide support for H3c.

5 Conclusion

How do citizens react when they feel that elections—as the most central mechanism for making their voices heard in the political process—are rigged? Do they descend into complete political apathy (exit), or do they seek to make themselves heard via different participatory channels (voice)? This study has addressed these questions by investigating the behavioral implications of electoral-integrity beliefs in Germany. It contributes to the extant literature by analyzing the influence of electoral-integrity beliefs on citizens’ political behavior at large, looking at turnout, vote choice, and nonelectoral political participation. Specifically, this study overcomes the restricted focus on turnout or voting for incumbent vs. opposition parties as evident in previous studies, paying additional attention to how perceptions of electoral integrity affect citizens’ propensity to vote for populist parties, to spoil their vote, or to engage in institutionalized and noninstitutionalized political activities in the offline and online realms. In doing so, the study adds new insights to previous research looking at different empirical cases or analyzing a limited set of behaviors from citizens’ political action repertoire only.

The study’s preregistered empirical analysis based on the preelection survey of the GLES (2022) has brought to light four key findings: First, citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity matter for their participation in elections. If citizens feel the electoral process is deficient and elections are not conducted in a free and fair manner, they are more likely to abstain from voting. Second, among those who (intend to) turn out to vote, perceptions of electoral integrity affect the choices that citizens opt for at the ballot box. Those who doubt the proper conduct of elections are less likely to vote for incumbent parties and more likely to vote for opposition parties, populist parties, or to spoil their vote. Third, the impact of electoral-integrity perceptions on nonelectoral forms of political participation is largely negligible. The only exception from this general finding is noninstitutionalized political activities in the online realm, which exhibit a higher prevalence among those doubting the integrity of elections. Fourth and finally, the present study does only provide weak evidence for the existence of a U-shaped relationship between electoral-integrity beliefs and political behavior. Accordingly, the theoretical argument that both citizens with particularly positive and citizens with particularly negative perceptions of electoral integrity exhibit a higher propensity to become politically active is not confirmed in the present study.

Considering the German case in more detail, our findings show that the share of citizens who feel that elections are compromised is relatively low, an observation that corresponds with prior assessments of objective electoral integrity in Germany. Nonetheless, even in such a context, some citizens feel that the electoral process is rigged. As this study highlights, the two main behavioral outcomes emanating from citizens’ doubts about the integrity of German elections are electoral disengagement and voting for the populist AfD. When confronted with a decision between voting for incumbent or (mainstream) opposition parties on the one hand and staying home on election day on the other, citizens who doubt the integrity of elections prefer to stay home. Yet when faced with a choice between staying home or voting for the populist AfD, the same citizens opt for the latter. Therefore, it appears that populist parties and actors who themselves regularly discredit the quality of elections benefit the most from increasing doubts about the proper conduct of elections—either indirectly via growing electoral disengagement among certain segments of the population and a weakening support base for their political opponents, or directly by mobilizing the votes of doubting citizens for their own electoral support. Currently, German citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs are still very positive overall, not giving cause for any (serious) concerns about the functioning of the electoral system. Yet, by primarily working to the advantage of the populist AfD (as well as German fringe parties that are unlikely to pass the 5% threshold), small shifts in citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs toward more negative viewpoints may already be putting a strain on government formation in the aftermath of future elections, with the potential to further diminish citizens’ confidence in the quality and efficiency of the electoral process. Consequently, it is imperative not only to maintain high levels of objective electoral integrity but also to shield the electoral system and citizens from unsubstantiated accusations of electoral fraud and misconduct as evidenced in the rhetoric of the AfD.

What are the broader implications of these findings beyond the German case? The empirical insights of this study suggest that doubts about the integrity of the electoral process and the proper conduct of elections come with a “triple penalty” for the functioning and viability of democratic systems. First, negative perceptions about the integrity of elections decrease citizens’ general inclination to take part in elections, inducing them to renounce one of their most basic democratic rights and to relinquish an opportunity to make their voices heard in the democratic process. Second, this decreased willingness to (s)elect political representatives via voting is not counterbalanced by an increased inclination for nonelectoral political activities, which could serve as a behavioral substitute and give back to citizens a means to affect politics beyond elections. Accordingly, there is hardly any compensation for the loss of political voice and influence evidenced in the electoral domain. Third and finally, among those who doubt the integrity of elections but turn out to vote nonetheless, the specific vote choices signal a clear preference for change over stability, with ambiguous repercussions for democratic well-being. While voting for (smaller) protest parties or casting an invalid ballot may “merely” serve to voice dissatisfaction, voting for populist parties may come with more far-reaching implications for the stability of a democratic system, especially if these parties exhibit a clear antidemocratic or authoritarian stance.

Contrasting this “triple penalty,” a more nuanced reading of this study’s insights suggests that doubts about the integrity of elections may at the same time assume the role of a “double corrective.” First, the fact that negative electoral-integrity perceptions transport a clear preference for anti-incumbent voting indicates that mechanisms of responsibility attribution are working and that citizens aim to “throw the rascals out” whom they consider responsible for violations of electoral integrity. Second, while electoral-integrity beliefs are mostly irrelevant for nonelectoral behavior, negative perceptions concerning the proper conduct of elections come with a more pronounced impetus to rely on online forms of noninstitutionalized participation. Accordingly, at least this type of participation may serve to counterbalance and compensate for a lower inclination to vote among those who doubt the integrity of elections and give them a way to voice their demands and affect politics from outside the electoral realm.

Ultimately, however, the extent to which doubts about the integrity of elections can perform a corrective function for democracy depends on the correctness and accuracy of citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs. If electoral fraud and misconduct are widespread, and citizens correctly perceive that the electoral process is rigged, then throwing the rascals out by voting for opposition parties or voicing demands via noninstitutionalized online participation clearly serve as democratic correctives. Yet if citizens’ perceptions of electoral integrity are misguided, and they mistakenly see elections as rigged despite their high objective quality, punishing incumbents at the ballot box for alleged electoral misconduct or voicing one’s dissatisfaction in online fora or petitions might do democracy a bad turn.

To shed light on these issues and further advance our understanding of the behavioral implications of electoral-integrity beliefs, future studies should therefore focus more specifically on the interplay of individual attributes (demand side), characteristics of political actors and their strategies (supply side), and the objective quality of elections in shaping citizens’ electoral-integrity beliefs and their impact on citizens’ political behavior.

Notes

This does not imply that the objective integrity of elections is irrelevant for individual citizens’ political participation, a topic to be addressed in more detail in future studies. For some descriptive findings at the aggregate level, see the study by Norris (2014, pp. 138–139).

Following these arguments, voting clearly establishes an institutionalized form of political participation as well (cf. van Deth 2014, p. 361). However, given the centrality of elections in representative democracies as well as the focus on electoral-integrity beliefs in this study, a separate analysis of voting is more expedient (cf. Carreras and İrepoğlu 2013, p. 612).

The preregistered analysis plan can be accessed at the following link: https://osf.io/53h9r.

Additional robustness checks show that excluding respondents who are too young to vote from the analysis does not alter this study’s substantive conclusions (see Tables R1 and R2 in the Supplementary Material).

See Table S1 in the Supplementary Material for descriptive statistics of all variables included in the analysis.

For a graphical illustration, see panels A1 and A2 in Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Material.

For a graphical illustration, see panels B1 and B2 in Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Material.

Additional robustness checks indicate that this finding is sensitive to the specification of the dependent variable. Using the original five-point scale for turnout intention, a U-shaped effect is also evident in a multivariate analysis (see Table R3 in the Supplementary Material).

Further nonregistered, exploratory analyses show that this incumbent vs. opposition effect is largely driven by voters of the FDP and small parties (“others”). See Table E1 and Fig. E1 in the Supplementary Material.

Given that only 44 respondents indicated an intention to cast an invalid ballot, the robustness of this finding has been assessed and confirmed in an additional robustness check using rare events logistic regression (King and Zeng 2001). See Table R4 in the Supplementary Material.

For a graphical illustration of these predicted probabilities, see Fig. S3 in the Supplementary Material.

For a graphical illustration of the predicted probabilities based on the models in Fig. 3, see Figs. S4 and S5 in the Supplementary Material.

For detailed results, see Figs. S6–S8 in the Supplementary Material.

References

Alvarez, R. Michael, D. Roderick Kiewiet, and Lucas Núñez. 2018. A taxonomy of protest voting. Annual Review of Political Science 21(1):135–154. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-120425.

Berlinski, Nicolas, Margaret Doyle, Andrew M. Guess, Gabrielle Levy, Benjamin Lyons, Jacob M. Montgomery, Brendan Nyhan, and Jason Reifler. 2021. The effects of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud on confidence in elections. Journal of Experimental Political Science https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.18.

Birch, Sarah. 2008. Electoral institutions and popular confidence in electoral processes: a cross-national analysis. Electoral Studies 27(2):305–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2008.01.005.

Birch, Sarah. 2010. Perceptions of electoral fairness and voter turnout. Comparative Political Studies 43(12):1601–1622. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010374021.

Booth, John A., and Mitchell A. Seligson. 2005. Political legitimacy and participation in Costa Rica: evidence of arena shopping. Political Research Quarterly 58(4):537–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290505800402.

Booth, John A., and Mitchell A. Seligson. 2009. The legitimacy puzzle in Latin America. Political support and democracy in eight nations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowler, Shaun, Thomas Brunell, Todd Donovan, and Paul Gronke. 2015. Election administration and perceptions of fair elections. Electoral Studies 38:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.01.004.

van der Brug, Wouter, and Meindert Fennema. 2003. Protest or mainstream? How the European anti-immigrant parties developed into two separate groups by 19991. European Journal of Political Research 42(1):55–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00074.

Carreras, Miguel, and Yasemin İrepoğlu. 2013. Trust in elections, vote buying, and turnout in Latin America. Electoral Studies 32(4):609–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.07.012.

van Deth, Jan W. 2003. Vergleichende Politische Partizipationsforschung. In Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft, ed. Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Ferdinand Müller-Rommel, 167–187. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

van Deth, Jan W. 2014. A conceptual map of political participation. Acta Politica 49(3):349–367. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.6.

Fogarty, Brian J., David C. Kimball, and Lea-Rachel Kosnik. 2020. The media, voter fraud, and the U.S. 2012 elections. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 0(0):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2019.1711383.

Fuchs, Dieter, and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. 1995. Citizens and the state: a changing relationship? In Citizens and the state. Beliefs in government series volume one, ed. Hans-Dieter Klingemann, Dieter Fuchs, 1–23. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fumarola, Andrea. 2020. The contexts of electoral accountability: electoral integrity performance voting in 23 democracies. Government and Opposition 55(1):41–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.13.

GLES. 2022. GLES cross-section 2021, pre-election. Köln: GESIS. https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13860. ZA7700 Data file version 2.0.0.

Gschwend, Thomas, and Frank Schimmelfennig. 2007. Introduction: designing research in political science—a dialogue between theory and data. In Research design in political science. How to practice what they preach, ed. Thomas Gschwend, Frank Schimmelfennig, 1–18. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

van Ham, Carolien. 2015. Getting elections right? Measuring electoral integrity. Democratization 22(4):714–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.877447.

Hooghe, Marc, and Sofie Marien. 2013. A comparative analysis of the relation between political trust and forms of political participation in Europe. European Societies 15(1):131–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2012.692807.

Hyde, Susan D. 2011. Catch us if you can: election monitoring and international norm diffusion. American Journal of Political Science 55(2):356–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00508.x.

Karp, Jeffrey A., Alessandro Nai, and Pippa Norris. 2018. Dial ‘F’ for fraud: explaining citizens suspicions about elections. Electoral Studies 53:11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2018.01.010.

King, Gary, and Langche Zeng. 2001. Logistic regression in rare events data. Political Analysis 9(2):137–163. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pan.a004868.

McAllister, Ian, and Stephen White. 2011. Public perceptions of electoral fairness in Russia. Europe-Asia Studies 63(4):663–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2011.566429.

McCann, James A., and Jorge I. Domínguez. 1998. Mexicans react to electoral fraud and political corruption: an assessment of public opinion and voting behavior. Electoral Studies 17(4):483–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(98)00026-2.

Mudde, Cas. 2004. The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39(4):541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x.

Nohlen, Dieter. 2014. Wahlrecht und Parteiensystem, 7th edn., Opladen: Budrich.

Norris, Pippa. 2013. The new research agenda studying electoral integrity. Electoral Studies 32(4):563–575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.07.015.

Norris, Pippa. 2014. Why electoral integrity matters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Norris, Pippa. 2018. Electoral integrity. In The Routledge handbook of elections, voting behavior and public opinion, ed. Justin Fisher, Edward Fieldhouse, Mark N. Franklin, Rachel Gibson, Marta Cantijoch, and Christopher Wlezien, 220–231. Abingdon: Routledge.

Norris, Pippa. 2019. Do perceptions of electoral malpractice undermine democratic satisfaction? The US in comparative perspective. International Political Science Review 40(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512118806783.

Norris, Pippa, Richard W. Frank, and Ferran Martínez i Coma. 2014. Measuring electoral integrity around the world: a new dataset. PS: Political Science & Politics 47(4):789–798. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096514001061.

Norris, Pippa, and Max Grömping. 2019. Electoral integrity worldwide. https://www.electoralintegrityproject.com/the-year-in-elections-2019. Accessed 16 Sept 2021.

Schmitt-Beck, Rüdiger, and Thorsten Faas. 2021. Wie frei und fair war die Bundestagswahl 2017? Elektorale Integrität aus Sicht der Bürgerinnen und Bürger. In Wahlen und Wähler: Analysen aus Anlass der Bundestagswahl 2017, ed. Bernhard Weßels, Harald Schoen, 139–161. Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-33582-3_8.

Schnaudt, Christian. 2019. Political confidence and democracy in Europe. Antecedents and consequences of citizens’ confidence in representative and regulative institutions and authorities. Cham: Springer.

Schnaudt, Christian, and Michael Weinhardt. 2018. Blaming the young misses the point: re-assessing young people’s political participation over time using the ‘identity-equivalence procedure’. methods, data, analyses 12(2):303–333. https://doi.org/10.12758/mda.2017.12.

Schnaudt, Christian, Caroline Hahn, and Elias Heppner. 2021. Distributive and procedural justice and political trust in Europe. Frontiers in Political Science 3:24. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.642232.

Smets, Kaat, and Carolien van Ham. 2013. The embarrassment of riches? A meta-analysis of individual-level research on voter turnout. Electoral Studies 32(2):344–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.12.006.

Teorell, Jan, Mariano Torcal, and José R. Montero. 2007. Political participation. Mapping the terrain. In Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: a comparative analysis, ed. Jan W. van Deth, José R. Montero, and Anders Westholm, 334–357. London: Routledge.

Theocharis, Yannis, and Jan W. van Deth. 2018a. Political participation in a changing world. Conceptual and empirical challenges in the study of citizen engagement. New York: Routledge.

Theocharis, Yannis, and Jan W. van Deth. 2018b. The continuous expansion of citizen participation: a new taxonomy. European Political Science Review 10(1):139–163. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773916000230.

Tyler, Tom R. 2006. Why people obey the law. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. 1995. Voice and equality. Civic voluntarism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wolf, Christof, Pablo Christmann, Tobias Gummer, Christian Schnaudt, and Sascha Verhoeven. 2021. Conducting general social surveys as self-administered mixed-mode surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly 85(2):623–648. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfab039.

ZDF. 2021. Wie die AfD Zweifel an der Briefwahl schürt. https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/afd-briefwahl-bundestagswahl-100.html. Accessed 17 Sept 2021.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions