Abstract

Background

Various studies have tried to delimit the predictors of hospital length of stay (LOS) for patients with exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (eCOPD), but have been disadvantaged by certain limiting factors.

Objective

Our goal was to prospectively identify predictors of LOS in these patients and to validate our results.

Design

This was a prospective cohort study.

Participants

Subjects were patients with eCOPD who visited 16 hospital emergency departments (EDs) and who were admitted to the hospital.

Main Measures

Data were recorded on possible predictor variables at the ED visit, on admission and 24 hours later, during hospitalization, and on discharge. LOS and prolonged LOS (≥ 9 days, considering the 75th percentile of LOS in our sample) were the outcomes of interest. Multivariate multilevel linear and logistic regression models were employed.

Results

A total of 1,453 patients were equally divided between derivation and validation samples. The hospital variable was the best predictor of LOS. Multivariate predictors of LOS, as log-transformed variables, were the hospital, baseline dyspnea and physical activity levels and fatigue at 24 hours, intensive care or intensive respiratory care unit admission, the need for antibiotics, and complications during hospitalization. Predictors of prolonged LOS were also the hospital, baseline dyspnea and fatigue at 24 hours, ICU or IRCU admission, and complications during hospitalization (AUC: 0.77). Models were validated in the validation sample (AUC: 0.75).

Conclusions

We identified a number of modifiable factors, including baseline dyspnea, physical activity level, and hospital variability, that influenced the LOS of patients with eCOPD who were admitted to the hospital.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Although its prevalence varies from country to country, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.1 Much of its impact is related to exacerbations—sudden worsening of symptoms, which may last for several days—which are part of the natural history of the disease in some patients.2,3 Exacerbations are also related to subsequent hospital admission and readmission, and account for more than 70 % of COPD costs due to emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations.4,5 Thus, identifying parameters that predict hospital admission and use of hospital services in patients experiencing an exacerbation of COPD (eCOPD) may be of help in establishing interventions or controls that improve patients' quality of life and prognosis while reducing the rate of admissions.6

Several research teams have attempted to identify predictors of length of stay (LOS) among patients hospitalized for an eCOPD.7–10 Much of this work has been hindered by methodological problems such as the use of a retrospective design, the use of administrative data with limited availability of relevant information, a lack of important variables or a focus exclusively on clinical parameters that exclude patient perception, and small sample size. Accurate identification of predictors of LOS could help in identifying interventions or preventive measures that could lessen the severity of eCOPD, reduce LOS, and avoid unnecessary use of health services.

The goal of this study was to identify factors related to LOS or prolonged LOS, as well and their relationship with outcomes two months following hospitalization, in a large prospective cohort of patients admitted to the hospital for an eCOPD.

METHODS

This prospective cohort study included patients drawn from 16 hospitals belonging to the Spanish National Health System (SNS), which covers the majority (99.8 %) of the population of Spain. All covered residents have free access to their primary care physician and to the EDs of the hospitals, and all of the hospital facilities have similar technological and human resources.

Patients with an eCOPD who visited the ED of any of these hospitals between June 2008 and September 2010 were informed of the goals of the study and invited to voluntarily participate. In order to take part in the study, patients were required to provide informed consent. All information was kept confidential. The institutional review boards of the participating hospitals approved the project. A more detailed description of the study protocol was published previously.11

Patients were eligible for the study if they presented to one of the participating EDs with symptoms consistent with an eCOPD. An eCOPD was defined as an event in the natural course of the disease characterized by a change in the patient's baseline dyspnea, cough, and/or sputum that was beyond normal day-to-day variations and that may have warranted a change in regular medication in a patient with underlying COPD.12 Patients with COPD that was newly diagnosed in the ED were included in the study only if the diagnosis was confirmed by spirometry within 60 days of the index episode at a time when the patient was stable.13 COPD was confirmed if the patient had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio < 70 %. Patients were excluded from the study if, at the time they were seen in the ED, they were experiencing an eCOPD complicated by a comorbidity such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism, lung cancer, or left cardiac insufficiency. Other exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of asthma, extensive bronchiectasis, sequelae of tuberculosis, pleural thickening, and restrictive diseases. Patients who did not wish to participate were also excluded.

Data Collected

Data collected upon arrival in the ED included socioeconomic data, information about the patient's respiratory status (arterial blood gases, respiratory rate, dyspnea), consciousness level measured by the Glasgow Coma Scale,14 and the presence of other disease conditions recorded in the Charlson Comorbidity Index.15 Data collected in the ED at the time a decision was made whether to admit the patient included symptoms, signs, and respiratory status at that moment.

For eligible eCOPD patients admitted to the hospital from the ED, we collected additional data directly from the medical record and from a direct interview with the patient on the first day after admission and on the day of discharge. Twenty-four hours after the index ED visit, patients were asked about their general health status before the exacerbation as well as their levels of dyspnea and physical activity (PA) when stable. To measure the level of dyspnea at baseline, we used the modified Medical Research Council (MRC) breathlessness scale, which comprises a five-grade categorization ranging from "I only get breathless with strenuous exercise" to "I am too breathless to leave the house."16 The level of dyspnea 24 hours after the index ED visit and at hospital discharge was measured with the specific question, "Rate your level of dyspnea today," using a seven-level scale from very severe to none, similar to the previously validated Borg dyspnea scale.17 Levels of PA were assessed using a seven-point scale, from "doesn't leave the house, life is limited to the bed or armchair" to "plays sports."18 The same assessments of general health, dyspnea, and physical activity were made at the time of discharge from the hospital.

Additional variables collected from medical records included baseline severity of COPD, as measured by FEV1% obtained from spirometry at a time when the patient's COPD was stable; hospital admissions due to eCOPD during the previous 12 months; baseline COPD therapies (inhaled short- or long-acting beta agonists, short- or long-acting anticholinergics, oral or inhaled corticosteroids, theophyllines, antibiotics, diuretics, and/or the need for noninvasive mechanical ventilation or long-term home oxygen therapy); therapies received in the ED, during admission, and at hospital discharge; the presence of chronic conditions used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index; and complications during hospitalization (including the appearance of any the following: pneumothorax, pulmonary thromboembolism, pneumonia, ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia, onset of a central nervous system event, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, proximal deep venous thrombosis, acute renal failure, septic shock, diabetic decompensation, atrial fibrillation, or severe heart failure). Reviewers were trained to systematically collect this information, and a precise manual was developed for the collection of data from the medical records (electronic or paper).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were length of hospital stay (continuous) and prolonged length of stay (LOS greater than nine days).

Statistical Analyses

The unit of analysis was the admitted patient. Among patients who had more than one eCOPD requiring an ED visit during the recruitment period, only the first visit was considered for the analysis. Patients who died during the admission period or whose LOS was 40 days or more (five patients) were excluded from the analysis.

The total sample was randomly divided into two groups: a derivation sample to identify predictors and a validation sample to test their reliability. Descriptive analyses for both samples included means and standard deviations (SD) of the LOS. The relationship between LOS and various parameters was analysed using the nonparametric Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis test. Because of the skewed distribution of LOS, in order to analyze it as a continuous variable, we performed a logarithmic transformation to satisfy the assumption of normality.

In the derivation sample, variables that were significant at the 0.20 level in the univariate analysis were considered as potential independent variables for the multivariate analysis. We then used mixed models to perform a multilevel multivariate analysis, adjusted by hospital, with the aim of identifying factors associated with LOS.19 The exponential of each beta-estimated parameter was interpreted as the ratio of LOS among the categories being compared, indicating how many times longer the stay was between the two levels being compared. An odds ratio greater than 1 represented an increase of LOS compared with the reference group. The model was validated in the validation sample.

For prolonged LOS, considering the 75th percentile of LOS in our sample, we dichotomized the outcome: LOS less than or equal to nine days, and LOS greater than nine days (prolonged LOS). To identify risk factors associated with prolonged LOS, multilevel univariate logistic analyses adjusted by centre were first performed in the derivation sample. Variables significant at the 0.20 level were entered into the multivariate analysis. The odds ratios (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) were calculated for the univariate and multivariate analyses. The predictive accuracy of the model was determined by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). We validated the model in the validation sample by determining the AUC, with its confidence interval, in each sample and calculating the p values for the receiver operating characteristic contrast.20

We also measured the association between prolonged length of stay and readmissions and death two months after the index hospitalization.

All effects were considered significant at p < 0.05, unless otherwise stated. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS for Windows statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Carey, NC, USA) and R© software version 2.13.0.

RESULTS

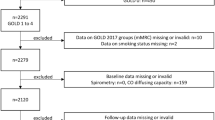

A total of 3,276 episodes of eCOPD that occurred between June 2008 and September 2010 were evaluated for the study. Of these, 198 (6 %) were excluded because COPD was complicated by other major pathologies at the time of ED visit (cardiovascular conditions, 59 [29.8 %]; pneumonia, 55 [27.8 %]; cancer, 21 [10.6 %]; other respiratory problems, 13 [6.6 %]; or other conditions, 50 [25.2 %]). Supplementary online Fig. 1 summarises the flow of patients through the recruitment and follow-up process.

Descriptive statistics and univariate analysis of the main sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of both samples in relation to length of stay are presented in Table 1. LOS varied among participant hospitals, and the treating hospital was the most important predictive variable for LOS. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the hospital was 0.22, which indicates that 22 % of the variability in LOS was accounted for by the hospitals, leaving 78 % of the variability accounted for by the patients. The relationship of various hospital characteristics with LOS is presented in the appendices (supplementary online Table 1).

From those parameters with p < 0.20 in the univariate analysis, a multivariate prediction model of length of stay as a continuous log-transformed variable was created (Table 2). Worse baseline dyspnea, as measured by the MRC scale, lower self-reported physical activity, dyspnea level at 24 hours of admission, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) or intensive respiratory care unit (IRCU), the need for intravenous antibiotic therapy, the presence of complications during hospitalization, and the hospital in which the patient was treated were all related to longer LOS. The same parameters were all validated in the validation sample. After the treating hospital, the next most relevant parameter related to LOS was the level of baseline dyspnea, followed by baseline physical activity level and self-reported level of fatigue 24 hours after being hospitalized for the index episode.

We evaluated the influence of the day, month, and season of hospital admission on LOS (see appendices, supplementary online Table 2). Although there was an association in the univariate analysis between LOS and those variables individually, this association did not remain in the multivariate model. As seen in supplementary online Table 3 (appendices), length of stay increased in relation to greater dyspnea 24 hours after admission and baseline dyspnea level.

Variables related to prolonged length of stay (greater than nine days) in the univariate analysis are presented in Table 3. Variables predictive of prolonged length of stay in the multivariate logistic regression model are presented in Table 4. These include worse baseline dyspnea, dyspnea level 24 hours after admission, admission to an ICU or IRCU, presence of complications during admission, and hospital in which the patient was treated (AUC: 0.77). The same parameters were validated in the validation sample (AUC, 0.75).

Length of stay greater than nine days was related to a higher probability of death at two months (31 patients [9.37 %] compared to 46 [4.10 %] with LOS of nine days or less; p = 0.0002 ), readmissions (123 [37.16 %] vs. 314 [27.99 %]; p = 0.0014) and new visits to the ED (142 [47.18 %] vs. 408 [40.60 %], p = 0.043).

DISCUSSION

This large prospective study of patients with an eCOPD who were admitted to one of 16 hospitals within the Spanish National Health System demonstrated that the most important variable in determining LOS was the hospital in which the patient was treated, followed by dyspnea and self-reported ability to perform physical activity.

Previous studies have also focused on determining predictive variables for LOS among patients hospitalized for an eCOPD.7,8,10,21–23 Factors identified, which have varied among studies, include respiratory rate or PCO2 at hospital arrival;9,23,25 comorbidities—both the total number and specific comorbidities such as heart failure or diabetes;8,21,23,25 day of the week on which the admission occurred;8,23 and social or family-related factors.7,22 The characteristics of these studies are diverse, including retrospective studies,8,21,24,25 those based on administrative or large databases,7,22,23,26 studies with small sample sizes,9,10 and those focusing essentially on clinical parameters.23 To our knowledge, no study to date has been conducted on a prospective cohort with a large sample size and with data collected regarding such a variety of variables.

Some of the predictors of LOS that we identified, such as baseline level of dyspnea and use of antibiotics, were also seen in previous studies.9,10 We evaluated most of the variables found in other studies, including day of the week, season, comorbidities, use of LTHOT or NIMV at home, number of medications used by the patient, and PCO2 at ED arrival, but none played a role in our predictive model. On the other hand, the number of previous medications, the use of LTHOT or NIMV at home, and PCO2 level at ED arrival were related to some of the variables included in our models, such as baseline dyspnea and fatigue level at the time of the exacerbation. While some studies have reported a relationship between certain of these variables and LOS, at least in our study, baseline dyspnea and fatigue seemed more predictive of LOS.

The most predictive parameter of LOS in our study was the hospital in which the patient was treated. This is not surprising, since several studies have demonstrated this kind of variability for various pathologies and procedures, including treatment of eCOPD patients.27 The participating hospitals all operate under the Spanish National Health System, and share similar human and technological resources. Although clinicians are trained to follow internationally accepted guidelines for treatment and follow-up of their patients, we did not evaluate what part of the variability was attributable to physicians or service characteristics. However, in evaluating hospital characteristics, we found that stays were likely to be longer in urban, university, tertiary, and larger hospitals. Variations in social and health care circumstances from one participating region to another, and thus among hospitals, could also affect outcomes.

These findings point to possible quality improvement solutions for reducing LOS while preserving the quality indicators in other outcomes. Practice inconsistencies in treating eCOPD must be reduced, which should lead to fewer differences in LOS among hospitals. Baseline dyspnea could be improved through respiratory rehabilitation programs,6 while proper and quick treatment of the current eCOPD may reduce fatigue and complications. Improving patients' physical activity, another predictor of LOS, may serve to improve several outcomes at the same time.28

Other parameters that are logically related to increased LOS due to severe presentations of eCOPD, such as admission to an ICU or IRCU, complications during hospitalization, and administration of antibiotic therapy, identify a complex evolution of the index eCOPD. Although these problems are acute, and may be unexpected, some are preventable through measures such as increased vaccination rates in this population, smoking cessation, respiratory rehabilitation, and increased physical activity—all less expensive interventions than extended LOS, treatment of eCOPD-related complications, or ICU or IRCU admission, though this has not been tested.2,4,6 Some studies have demonstrated that LOS can be reduced through interventions such as telemedicine or by implementing practice guidelines.24,26 As is evident from our data, prolonged LOS is also related to other adverse outcomes such as increased mortality and higher readmission rates in the two months after the index admission. Therefore, interventions directed at reducing variability in LOS may have important consequences for patient health and health care costs.

Strengths of our study include the prospective design, the large sample of patients recruited from various hospitals, and the wide range of variables evaluated. The careful derivation and validation of our predictive models, following current recommendations for such studies, adds robustness to our conclusions.

Limitations of our study are primarily related to the study design. Missing data in cohort studies is probably the most relevant bias in this context. Nevertheless, the rate of missing data was low in our study. In addition, although we included a comprehensive range of clinical variables that were evaluated, it is possible that we omitted some of the clinical, social, or health care parameters—including provider characteristics—that may influence LOS. And while the predictive ability of our models—as measured by the AUC—were good, there is still room for improvement, suggesting that parameters not included in our study would have helped to better explain what is happening with the difficult-to-predict outcome of LOS.

In conclusion, we identified a group of parameters that predicted LOS or prolonged LOS among patients hospitalized for an eCOPD. Some of those parameters are modifiable through different types of interventions, such as improvement in a patient's level of dyspnea or prevention of complications of the eCOPD at the patient level and hospital variability at the provider level. As with many other chronic pathologies, prevention is a key factor in patients with COPD. Promoting exercise in order to reduce LOS would improve disease outcomes and would also help reduce fragility and dependency in these generally older patients, which may contribute to greater LOS. Reduction in LOS among patients hospitalized for eCOPD would not only help reduce the cost of health care, but would improve patient health as well. Complications associated with hospital admission, which in these patients tend to be more severe, can diminish health status and independence, key factors in survival expectations and patient quality of life.

References

Atsou K, Chouaid C, Hejblum G. Variability of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease key epidemiological data in Europe: systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:7.

Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1341–51.

Pauwels RA, Rabe KF. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Lancet. 2004;364(9434):613–20.

Niewoehner DE. The impact of severe exacerbations on quality of life and the clinical course of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2006;119(10 Suppl 1):38–45.

Buist AS, Vollmer WM, McBurnie MA. Worldwide burden of COPD in high- and low-income countries. Part I. The burden of obstructive lung disease (BOLD) initiative. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(7):703–8.

Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA. COPD exacerbations: defining their cause and prevention. Lancet. 2007;370(9589):786–96.

Agboado G, Peters J, Donkin L. Factors influencing the length of hospital stay among patients resident in Blackpool admitted with COPD: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2012;2(5).

de la Iglesia F, Valino P, Pita S, Ramos V, Pellicer C, Nicolas R, et al. Factors predicting a hospital stay of over 3 days in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Intern Med 2002 Jun;251(6):500–7.

Mushlin AI, Black ER, Connolly CA, Buonaccorso KM, Eberly SW. The necessary length of hospital stay for chronic pulmonary disease. JAMA. 1991;266(1):80–3.

Tsimogianni AM, Papiris SA, Stathopoulos GT, Manali ED, Roussos C, Kotanidou A. Predictors of outcome after exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1043–8.

Quintana JM, Esteban C, Barrio I, Garcia-Gutierrez S, Gonzalez N, Arostegui I, et al. The IRYSS-COPD appropriateness study: objectives, methodology, and description of the prospective cohort. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:322.

Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Buist SA, Calverley P, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(6):532–55.

Gold PM. The 2007 GOLD Guidelines: a comprehensive care framework. Respir Care. 2009;54(8):1040–9.

Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. Pract Scale Lancet. 1974;2(7872):81–4.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Fletcher CM, Elmes PC, Fairbairn AS, Wood CH. The significance of respiratory symptoms and the diagnosis of chronic bronchitis in a working population. Br Med J. 1959;2(5147):257–66.

Hareendran A, Leidy NK, Monz BU, Winnette R, Becker K, Mahler DA. Proposing a standardized method for evaluating patient report of the intensity of dyspnea during exercise testing in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:345–55.

Esteban C, Quintana JM, Aburto M, Moraza J, Arostegui I, Espana PP, et al. The health, activity, dyspnea, obstruction, age, and hospitalization: prognostic score for stable COPD patients. Respir Med. 2011;105(11):1662–70.

Moran JL, Solomon PJ. A review of statistical estimators for risk-adjusted length of stay: analysis of the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Adult Patient Data-Base, 2008–2009. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:68.

Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez JC, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:77.

Incalzi RA, Pedone C, Onder G, Pahor M, Carbonin PU. Predicting length of stay of older patients with exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Aging (Milano). 2001;13(1):49–57.

Wong AW, Gan WQ, Burns J, Sin DD, van Eeden SF. Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: influence of social factors in determining length of hospital stay and readmission rates. Can Respir J. 2008;15(7):361–4.

Wang Y, Stavem K, Dahl FA, Humerfelt S, Haugen T. Factors associated with a prolonged length of stay after acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:99–105.

Kong GK, Belman MJ, Weingarten S. Reducing length of stay for patients hospitalized with exacerbation of COPD by using a practice guideline. Chest. 1997;111(1):89–94.

Villalta J, Sequeira E, Cereijo AC, Siso A, de la Sierra A. [Factors predicting a short length of stay for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Med Clin (Barc ). 2005;124(17):648–50.

Bashshur RL, Shannon GW, Smith BR, Alverson DC, Antoniotti N, Barsan WG, et al. The Empirical Foundations of Telemedicine Interventions for Chronic Disease Management. Telemed J E Health 2014 Jun 26.

George PM, Stone RA, Buckingham RJ, Pursey NA, Lowe D, Roberts CM. Changes in NHS organization of care and management of hospital admissions with COPD exacerbations between the national COPD audits of 2003 and 2008. QJM. 2011;104(10):859–66.

Seemungal TA, Hurst JR, Wedzicha JA. Exacerbation rate, health status and mortality in COPD–a review of potential interventions. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:203–23.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CONTRIBUTORS

We are grateful for the support of the 16 participating hospitals, as well as the ED physicians, other clinicians, and staff members of the various services, research, quality units, and medical records sections of these hospitals. We also gratefully acknowledge the patients who participated in the study. The authors also acknowledge the editorial assistance provided by Patrick Skerrett.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (PI 06\1010, PI06\1017, PI06\714, PI06\0326, PI06\0664); Department of Health of the Basque Country, Department of Education, Universities and Research of the Basque government (UE09+/62); the Research Committee of the Hospital Galdakao; and the thematic networks-REDISSEC (Red de Investigación en Servicios de Salud en Enfermedades Crónicas) of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Conflict of Interest

The authors each declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The IRYSS-COPD group included the following co-investigators: Dr. Jesús Martínez-Tapias (Dirección Económica, Área Gestión Sanitaria Sur Granada); Alba Ruiz (Hospital de Motril, Granada); Dr. Eduardo Briones, Dra. Silvia Vidal (Unidad de Calidad, Hospital Valme, Sevilla);Dr. Emilio Perea-Milla, Francisco Rivas (Servicio de Epidemiología, Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga–REDISSEC); Dr. Maximino Redondo (Servicio de Laboratorio, Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga-REDISSEC); Javier Rodríguez Ruiz (Responsable de Enfermería del Área de Urgencias, Hospital Costa del Sol, Málaga); Dra. Marisa Baré (Epidemiología y Evaluación, Corporació Sanitaria Parc Taulí-CSPT-REDISSEC, Sabadell), Dr. Manel Lujan, Dra. Concepción Montón, Dra. Amalia Moreno, Dra. Josune Ormaza, Dr. Javier Pomares (Servicio de Neumología, CSPT); Dr. Juli Font (Medicina, Servicio de Urgencias; CSPT), Dra. Cristina Estirado, Dr. Joaquín Gea (Servicio de Neumología, Hospital del Mar, Barcelona); Dra. Elena Andradas, Dr. Juan Antonio Blasco, Dra. Nerea Fernández de Larrea (Unidad de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias, Agencia Laín Entralgo, Madrid); Dra. Esther Pulido (Servicio de Urgencias, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia); Dr. Jose Luis Lobo (Servicio de Neumología, Hospital Txagorritxu, Araba); Dr. Mikel Sánchez (Servicio de Urgencias, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia); Dr. Luis Alberto Ruiz (Servicio de Respiratorio, Hospital Cruces, Bizkaia); Dra. Ane Miren Gastaminza (Hospital San Eloy, Bizkaia); Dr. Ramon Agüero (Servicio de Neumología, Hospital Marques de Valdecilla, Santander); Dr. Gabriel Gutiérrez (Servicio de Urgencias, Hospital Cruces, Bizkaia); Dra. Belén Elizalde (Dirección Territorial de Gipuzkoa); Dr. Felipe Aizpuru (Unidad de Investigación, Hospital Txagorritxu, Álava/REDISSEC); Dra.Inmaculada Arostegui (Departamento de Matemática Aplicada, Estadística e Investigación Operativa, UPV-REDISSEC; Amaia Bilbao, Hospital de Basurto-(REDISSEC); Dr. Eva Tabernero and Carmen M. Haro (Hospital de Santa Marina); Dr. Cristóbal Esteban (Servicio de Neumología, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo-REDISSEC, Bizkaia); Dra. Nerea González, Susana Garcia, Iratxe Lafuente, Urko Aguirre, Irantzu Barrio; Miren Orive, Edurne Arteta, Dr. Jose M. Quintana (Unidad de Investigación, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Bizkaia/REDISSEC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

supplementary online Table 1

(DOCX 20 kb)

supplementary online Table 2

(DOCX 20 kb)

supplementary online Table 3

(DOCX 21 kb)

supplementary online Figure 1

(DOCX 46 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quintana, J.M., Unzurrunzaga, A., Garcia-Gutierrez, S. et al. Predictors of Hospital Length of Stay in Patients with Exacerbations of COPD: A Cohort Study. J GEN INTERN MED 30, 824–831 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3129-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3129-x