Abstract

Recent evidence shows that rising wage inequality in industrialized countries can partially be attributed to trade integration. However, it is unclear what the mechanisms behind this relationship are. Previous explanations pointed toward the displacement of mid-wage manufacturing workers as a response to rising imports. However, for Germany it has been shown that rising exports likewise create manufacturing jobs, indicating that industry-based explanations fall short. We argue that focusing on changes of the occupational composition, as well as changes in the occupation-specific median and top wages, may help to explain the effects of trade on inequality. We draw on a task-based approach, theories of power relations between occupations, as well as self-selection by firms to arrive at predictions about the mediating role of occupations. We analyze German trade relations with China between 1994 and 2010 using social security data (BHP, IEB) and data on international trade flows (COMTRADE). Applying an instrumental variable approach, we find that, surprisingly, imports do not affect wage inequality. Instead, rising exports to China are responsible for the effects of trade integration on inequality as they increase wage dispersion within German labor market regions. Although increased trade integration alters the occupational task composition, we find no evidence that these shifts mediate the effects of exports on wage inequality. Instead, exports increase the wages of some occupations, especially for top earners, highlighting the importance of focusing on within-occupation dynamics.

Zusammenfassung

Neuere Erkenntnisse zeigen, dass sich die steigende Lohnungleichheit in industrialisierten Ländern partiell auf internationale Handelsverflechtungen zurückführen lässt. Noch ist jedoch unklar, welche Mechanismen hinter diesem Zusammenhang stehen. Bisherige Erklärungen stellen heraus, dass steigende Importe Arbeitsplätze im mittleren Lohnsegment des Produktionssektors vernichten. Für Deutschland hat sich jedoch gezeigt, dass Exporte in ähnlichem Maße neue Arbeitsplätze schaffen. Branchenbasierte Erklärungen scheinen also zu kurz zu greifen. Wir argumentieren, dass Veränderungen in der Berufsstruktur und in den berufsspezifischen Median- und Toplöhnen helfen können, den Zusammenhang zwischen Handelsbeziehungen und Lohnungleichheit zu erklären. Um Vorhersagen über die Rolle des Berufs zu treffen, greifen wir auf einen Task-Based-Approach sowie Theorien zu Machtverhältnissen zwischen Berufen und Selbstselektion von Firmen zurück. Wir analysieren die Handelsbeziehungen zwischen China und Deutschland für die Jahre 1994 bis 2010 und greifen dazu auf Sozialversicherungsdaten (Betriebs-BHP, IEB) sowie Daten zum internationalen Handelsverkehr (COMTRADE) zurück. Mithilfe von Instrumentenvariablenschätzern zeigen wir, dass Importe die Lohnungleichheit überraschenderweise nicht beeinflussen. Stattdessen sind steigende Exporte nach China für die wachsende Lohnstreuung in Arbeitsmarktregionen verantwortlich. Obwohl zunehmende Handelsverflechtungen die regionale Taskstruktur verändern, finden wir keine Anzeichen dafür, dass diese Veränderungen als Mediator für den Effekt von Exporten auf Lohnungleichheit dienen. Vielmehr scheinen Exporte die Löhne in einigen ausgewählten Berufen zu erhöhen, insbesondere für Spitzenverdiener. Die Ergebnisse unterstreichen die Bedeutung von innerberuflichen Dynamiken für die Erklärung sozialer Ungleichheit.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As Dauth et al. (2014) show, trade with Eastern Europe has risen to an even higher degree and has had a more severe impact on employment in Germany. In this study, we focus solely on China, as trade with Eastern Europe mostly depicts intra-industry trade. The theoretical predictions regarding changes in the occupational composition are thus not as clear-cut and likely differ. We thus emphasize that our results should not be generalized to all forms of trade relations.

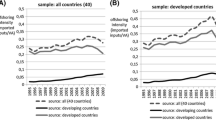

For Germany, Bartels (2019) observes that although trade exposure has not been associated with increasing inequality for most of German economic history, such an association, however, may have existed since the 1990s.

The prediction for occupations marked by a mixture of routine and cognitive tasks, as well as those with mixed manual and nonroutine content is ambivalent.

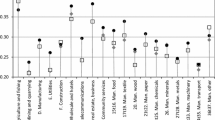

Data source: see the section “Data”. Wages refer to mean daily wages in 1994. Task categories refer to the tasks that are predominant in a three-digit occupation.

It is important to note that, like the first mechanism, this theory relies on the assumption of imperfect labor mobility (between firms in this case), because firms pay similar workers different wages. Furthermore, note that the effects of imports in the second and third mechanisms are ambiguous, as increased competition can eliminate unproductive low-paying firms (hence raising average wages), but also decrease the capacity of the remaining relatively unproductive firms in the market to pay higher wages.

Replication files can be found at malte-reichelt.com. Note that the data are only available via remote access at the Research Data Centre (FDZ) of the Federal Employment Agency at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB).

Since wages are censored above the social security contributions limits, we use the differences in wages at the 85th and the 15th percentiles instead of the lowest and highest wages.

While Autor et al. (2013) use a 10-year lag for employment levels, this is not a feasible choice for our analysis of the sub-period 1994–2002 owing to the German reunification in 1990, and moreover, our accessible employer–employee data start from 1988.

Additionally, previous research has shown that trade shocks, when instrumented with this procedure, tend to operate largely independently of technology shocks, which could otherwise present a confounder (Autor et al. 2015).

Dauth et al. (2014) also find no statistically significant effects on manufacturing employment when examining export potential to China specifically. They do, however, find export potential overall to significantly increase employment prospects.

As we cannot precisely measure which occupations were truly responsible for the production of a good, we arrive at the distribution of main occupational tasks per average imported or exported product by first calculating the share each three-digit industry holds of the total imported or exported goods and then weighting these shares by the number of jobs for each occupational main task in each industry.

We also estimated regressions with the median wage at the regional labor market level as the dependent variable. The results show that there is indeed no statistically significant reaction of wages to import shocks. One reason for constant wages may be that workers move occupations within the same firm, as wage cuts are relatively rare in Germany.

References

Acemoglu, Daron, and David H. Autor. 2010. Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. NBER Working Paper (16082).

Akçomak, Semih, Suzanne Kok and Hugo Rojas-Romagosa. 2016. Technology, offshoring and the task content of occupations in the United Kingdom. International Labour Review 155:201–230.

Autor, David H. 2013. The “task approach” to labor markets: an overview. Journal for Labour Market Research 46:185–199.

Autor, David H., David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. The American Economic Review 103(6):2121–2168.

Autor, David H., David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson. 2015. Untangling trade and technology: Evidence from local labour markets. The Economic Journal 125(584):621–646.

Autor, David H., Frank Levy and Richard J. Murnane. 2003. The skill content of recent technological change: An empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118(4):1279–1333.

Bartel, Ann, Casey Ichniowski and Kathryn Shaw. 2007. How does information technology affect productivity? Plant-level comparisons of product innovation, process improvement, and worker skills. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122(4):1721–1758.

Bartels, Charlotte. 2019. Top incomes in Germany, 1871–2014. Journal of Economic History forthcoming.

Becker, Sascha O., and Marc-Adreas Muendler. 2015. Trade and tasks: An exploration over three decades in Germany. Economic Policy 30(84):589–641.

Bhagwati, Jagdish. 1995. Trade and wages: Choosing among alternative explanations. Economic Policy Review 1(1):42–47.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2002. At home and abroad: US labor market performance in international perspective. Russell Sage Foundation. New York.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, and Karl Ulrich Mayer, 1988. Arbeitsmarktsegmentation in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Eine empirische Überprüfung von Segmentationstheorien aus der Perspektive des Lebenslaufs. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, 40:262–283.

Blossfeld, Hans-Peter, Erik Klijzing, Melinda Mills and Karin Kurz. Eds. 2006. Globalization, uncertainty and youth in society. Routledge.

Bol, Thijs, and Kim A. Weeden. 2015. Occupational closure and wage inequality in Germany and the United Kingdom. European Sociologial Review 31(3):354–369.

Brady, David. 2009. Economic globalization and increasing earnings inequality in affluent democracies. Research in the Sociology of Work 18:149–181.

Brady, David, and Michael Wallace. 2000. Spatialization, foreign direct investment, and labor outcomes in the American States, 1978–1996. Social Forces 79(1):1978–1996.

Brady, David, Jason Beckfield and Wei Zhao. 2007. The consequences of economic globalization for affluent democracies. Annual Review of Sociology 33:313–334.

Bustos, Paula. 2011. The impact of trade liberalization on skill upgrading evidence from Argentina. Working Papers 559, Barcelona Graduate School of Economics.

Damelang, Andreas, Florian Schulz and Basha Vicari. 2015. Institutionelle Eigenschaften von Berufen und ihr Einfluss auf berufliche Mobilität in Deutschland. Schmollers Jahrbuch 135:307–334.

Dauth, Wolfgang, Sebastian Findeisen and Jens Suedekum. 2014. The rise of the East and the Far East: German labor markets and trade integration. Journal of the European Economic Association 12(6):1643–1675.

Dengler, Katharina, Britta Matthes and Wiebke Paulus. 2014. Occupational tasks in the German labour market—an alternative measurement on the basis of an expert database. FDZ Methodenreport 12.

DiPrete, Thomas A. 2002. Life course risks, mobility regimes, and mobility consequences: A comparison of Sweden, Germany, and the United States. American Journal of Sociology 108(2):267–309.

DiPrete, Thomas A. 2005. Labor markets, inequality, and change: A European perspective. Work and Occupations 32(2):119–139.

DiPrete, Thomas A., and Patricia A. McManus. 1996. Institutions, technical change, and diverging life chances: Earnings mobility in the United States and Germany. American Journal of Sociology 102(1):34–79.

Dustmann, Christian, Johannes Ludsteck and Uta Schoenberg. 2009. Revisiting the German wage structure. Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(2):843–881.

Eberle, Johanna, Peter Jacobebbinghaus, Johannes Ludsteck and Julia Witer. 2014. Generation of time-consistent industry codes in the face of classification changes. FDZ Methodenreport, 5(2008).

Fajgelbaum, Pablo D., and Amit K Khandelwal. 2016. Measuring the unequal gains from trade. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131(3):1113–1180.

Feenstra, Robert C., and Alan M. Taylor. 2017. International Economics, 4th edition. New York: Macmillan.

Felbermayr, Gabriel, Giammario Impullitti and Julien Prat. 2018. Firm dynamics and residual inequality in open economies. Journal of the European Economic Association 16(5):1476–1539.

Goos, Maarten, and Alan Manning. 2007. Lousy and lovely jobs: The rising polarization of work in Britain. The Review of Economics and Statistics 89(1):118–133.

Goos, Maarten, Alan Manning and Anna Salomons. 2014. Explaining job polarization: Routine-biased technological change and offshoring. American Economic Review 104(8):2509–2526.

Grant, Don Sherman, and Michael Wallace. 1994. The political economy of manufacturing growth and decline across the American States, 1970–1985. Social Forces 73(1):33–63.

Grossman, Gene M., and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. 2008. Trading tasks: A simple theory of offshoring. The American Economic Review 98(5):1978–1997.

Gu, Grace W., Samreen Malik, Dario Pozzoli and Vera Rocha. 2020. Trade-induced skill polarization. Economic Inquiry 58(1), 241–259.

Hällsten, Martin, Tomas Korpi and Michael Tåhlin. 2010. Globalization and uncertainty: Earnings volatility in Sweden, 1985–2003. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 49(2):165–189.

Helpman, Elhanan, Oleg Itskhoki, Marc-Andreas Muendler and Stephen J. Redding. 2017. Trade and inequality: From theory to estimation. Review of Economic Studies 84(1):357–405.

Kambourov, Gueorgui, and Iourii Manovskii. 2009. Occupational specificity of human capital. International Economic Review 50(1):63–115.

Keller, Wolfgang, and Hâle Utar. 2016. International trade and job polarization: Evidence at the worker level. Technical report, Working Paper: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kemeny, Thomas, and David Rigby. 2012. Trading away what kind of jobs? globalization, trade and tasks in the us economy. Review of World Economics 148(1):1–16.

Kim, ChangHwan, and Arthur Sakamoto. 2008. The rise of intra-occupational wage inequality in the United States, 1983 to 2002. American Sociological Review 73(2):129–157.

Kracke, Nancy, Malte Reichelt and Basha Vicari. 2018. Wage losses due to overqualification: The role of formal degrees and occupational skills. Social Indicators Research 139(3):1085–1108.

Levy, Frank, and Richard J. Murnane. 2004. The new division of labor: how computers change the way we work. Princeton University Press, New York.

Li, Hongbin, Lei Li, Binzhen Wu and Yanyan Xiong. 2012. The end of cheap Chinese labor. Journal of Economic Perspectives 26(4):57–74.

Liu, Yujia, and Grusky, David B. 2013. The payoff to skill in the third industrial revolution. American Sociological Review 118(5):1330–1374.

Mahutga, Matthew C., Anthony Roberts and Ronald Kwon. 2017. The globalization of production and income inequality in rich democracies. Social Forces 96(1):181–214.

Matthes, Britta, Bernhard Christoph, Florian Janik and Michael Ruland. 2014. Collecting information on job tasks—an instrument to measure tasks required at the workplace in a multi-topic survey. Journal for Labour Market Research 47(4):273–297.

Morris, Martina, and Bruce Western. 1999. Inequality in earnings at the close of the twentieth century. Annual Review of Sociology 25(1):623–657.

Mouw, Ted, and Arne Kalleberg. 2010. Occupations and the structure of wage inequality in the United States, 1980s to 2000s. American Sociological Review 75(3):402–431.

Neckerman, Kathryn M., and Florencia Torche. 2007. Inequality: causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology 33:335–357.

Piketty, Thomas, and Emmanuel Saez. 2014. Inequality in the long run. Science 344(6186):838–843.

Rees, Kathleen, and Jan Hathcote. 2004. The US textile and apparel industry in the age of globalization. Global Economy Journal 4(1):1524–5861.

Reichelt, Malte, and Martin Abraham. 2017. Occupational and regional mobility as substitutes: A new approach to understanding job changes and wage inequality. Social Forces 95(4):399–1426.

Richardson, J. David. 1995. Income inequality and trade: how to think, what to conclude. Journal of economic perspectives 9(3):33–55.

RWI 2018. Überprüfung des Zuschnitts von Arbeitsmarktregionen für die Neuabgrenzung des GRW Fördergebiets ab 2021. Endbericht Studie im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi) 16. März 2018.

Schwengler, Barbara, and Jan Binder. 2007. Vorschlag und Neuzuschnitt der Arbeitsmarktregionen im Raum Berlin-Brandenburg. Sozialer Fortschritt 56(7/8):194–199.

Sklair, Leslie. 2002. Capitalism and its alternatives Volume 65. Oxford University Press.

Solga, Heike, and Dirk Konietzka. 1999. Occupational matching and social stratification: Theoretical insights and empirical observations taken from a German–German comparison. European Sociological Review 15(1):25–47.

Spilerman, Seymour. 2008. How globalization has impacted labour: A review essay. European Sociological Review 25(1):73–86.

Spitz-Oener, Alexandra. 2006. Technical change, job tasks, and rising educational demands: Looking outside the wage structure. Journal of Labor Economics 24(2):235–270.

Tomaskovic-Devey, Donald, Peter Jacobebbinghaus and Silvia Melzer. 2016. The organizational production of earnings inequalities in Germany, 1994–2010. SSRN Working Paper.

Wallace, Michael, Gordon Gauchat and Andrew S. Fullerton. 2011. Globalization, labor market transformation, and metropolitan earnings inequality. Social Science Research 40(1):15–36.

Williams, Mark, and Thijs Bol. 2018. Occupations and the wage structure: The role of occupational tasks in Britain. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 53:16–25.

Yuasa, Masae. 2001. Globalization and flexibility in the textile/apparel industry of Japan. Asia Pacific Business Review 8(1):80–101.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank David Brady, Simon Janssen, Wolfgang Dauth, and the participants of the ASA 2019 sessions on Organizations, Occupations, and Work for helpful discussions and comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reichelt, M., Malik, S. & Suesse, M. Trade and Wage Inequality: The Mediating Roles of Occupations in Germany. Köln Z Soziol 72 (Suppl 1), 535–560 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00680-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00680-5