Abstract

The present article investigates gender discrimination in recruitment for two male-dominated occupations (mechanics and IT professionals). We empirically test two different explanatory approaches to gender discrimination in hiring; namely, statistical discrimination and taste-based discrimination. Previous studies suggest that, besides job applicants’ characteristics, organisational features play a role in hiring decisions. Our article contributes to the literature on gender discrimination in the labour market by investigating its opportunity structures located at the recruiter, job and company level, and how gender discrimination varies across occupations and countries.

The analysed data come from a factorial survey experiment conducted in four countries (Bulgaria, Greece, Norway and Switzerland). Real job advertisements were sampled, and the recruiters in charge of hiring for these positions (n = 1,920) rated up to ten hypothetical CVs (vignettes). We find gender discrimination in Bulgaria and Greece and to a lesser degree in Switzerland, but not in Norway. The degree of gender discrimination appears to be greater in mechanics than in IT. Multivariate analyses that test a number of opportunity structures for discrimination suggest that mechanisms of statistical discrimination rather than those of taste-based discrimination might be at work.

Zusammenfassung

Im vorliegenden Beitrag wird die Geschlechterdiskriminierung im Rekrutierungsprozess in zwei männlich dominierten Berufen (Mechanikerinnen und Mechaniker, Informatikerinnen und Informatiker) untersucht. Dabei werden verschiedene Erklärungsansätze für das Vorkommen einer systematischen Benachteiligung von Frauen empirisch überprüft, nämlich statistische Diskriminierung und Taste-based-Diskriminierung. Frühere Studien haben ergeben, dass nicht nur individuelle Eigenschaften von Bewerberinnen und Bewerbern sondern auch organisationale Charakteristika eine Rolle spielen. Die Studie erweitert die Forschungsliteratur zu Geschlechterdiskriminierung, indem ihre Opportunitätsstrukturen auf Ebene von Personalreferentinnen und Personalreferenten, Stellen und Betriebe untersucht werden und ihre kontextspezifische Wirkungsweise in unterschiedlichen Berufen sowie Ländern aufgezeigt wird.

Die Analysen basieren auf einer Vignettenstudie, die in vier Ländern durchgeführt wurde (Bulgarien, Griechenland, Norwegen und Schweiz). Dazu wurden reale Stellenanzeigen gesampelt und die zuständigen Personalverantwortlichen (n = 1920) befragt. Jede befragte Person bewertete bis zu zehn hypothetische Lebensläufe (Vignetten). Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass Geschlechterdiskriminierung vor allem in Bulgarien, Griechenland und zu einem geringeren Teil auch in der Schweiz vorkommt, nicht jedoch in Norwegen. Darüber hinaus ist das Ausmaß der Geschlechterdiskriminierung größer im Mechanikerberuf als in IT-Berufen. Die multivariaten Analysen, die mehrere Opportunitätsstrukturen von Diskriminierung untersuchen, belegen, dass eher Mechanismen der statistischen Diskriminierung als jene der Taste-based-Diskriminierung am Werk sind.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The educational attainment of women has considerably improved owing to educational expansion. Today, girls and women outperform boys and men in school and higher education respectively. Moreover, women’s enrolment in subjects previously deemed the domains of men has increased considerably (DiPrete and Buchmann 2013). Likewise, the considerable growth of the service sector (Hakim 1996) has changed labour market structures in favour of women’s employment (Charles 2003). Nevertheless, labour markets remain highly segregated by gender. Researchers have shown links between horizontal gender segregation—the unequal distribution of gender across occupations—and vertical segregation, that is, where female-dominated jobs pay less and offer fewer opportunities for professional development (England 2010; Leuze and Strauß 2016). Further, organisational constraints may push women into “family-friendly” occupations, which offer flexibility or enable part-time work in order to combine employment with domestic activities (Levanon et al. 2009).

Sociologists recurrently rely upon three explanations for the persistence of horizontal gender segregation. First, horizontal gender segregation is partly the result of self-selective behaviour. Women may be attracted to “family-friendly” occupations (e.g., in the service sector) rather than occupations in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM, see Herman et al. 2013; Mastekaasa and Smeby 2008). Second, employers’ preferences for applicants of a certain gender—independent of the job candidates’ skills and abilities—can perpetuate horizontal gender segregation (Kricheli-Katz 2019). Such employer behaviour is usually known as gender discrimination in hiring (Birkelund et al. 2019; Kübler et al. 2018; Riach and Rich 2006). Third, horizontal segregation may be the outcome of aggregation processes such as the de-valuation of female-dominated occupations (Levanon et al. 2009; Leuze and Strauß 2016; Ochsenfeld 2014).

In this article, we provide further insight into the second field of explanations. For many decades, extensive economic and sociological literature has focused on gender discrimination in hiring. The two most prominent explanations—Becker’s (1957) work on taste-based discrimination and the theory of statistical discrimination (Arrow 1973; Phelps 1972)—are rooted in economics. As such, both theoretical approaches assume that propensities to discriminate are constant over time and across social contexts (Keuschnigg and Wolbring 2016). The conditions under which employers’ preferences translate into unequal treatment of job candidates remain underexplored. Reskin (2003), for instance, has argued that prejudices and stereotypes may only unfold if organisational contexts and practices allow them to do so. Peterson and Saporta (2004) have termed this phenomenon the “opportunity structure for discrimination”.

These opportunity structures have a range of occupational characteristics. According to Kübler et al. (2018), female candidates are subject to some degree of discrimination in male-dominated, particularly STEM, occupations. The degree of gender discrimination in this male-dominated field may vary according to the extent of gender-stereotyping attached to a given occupation (Yavorsky 2019). STEM occupations are relevant to study, as the phenomenon of the “leaky pipeline”, i.e. the decreasing proportion of women at the various qualification levels and career stages, is particularly salient (Blickenstaff 2005; Herman et al. 2013). Exactly how this phenomenon differs among the specific occupations within the broader STEM cluster remains under-researched, as does the degree to which gender discrimination can be explained by recruiter preferences and the characteristics of the vacancy and company. Last but not least, little is known about how discrimination varies across country contexts (Quillian et al. 2019).

We take the sociological critique of neoclassic economic models of discrimination as a starting point and contribute to the existing body of literature by analysing the opportunity structures for gender discrimination in different occupational and national contexts. We provide a case study of recruiter behaviour in the hiring process in four countries for two male-dominated occupations—namely, mechanics and information technology (IT) professionals, both technical occupations that nevertheless vary in terms of required social skills (Barone 2011), status (Kricheli-Katz 2019) and educational pathways. We address the following questions:

1. How do recruiters hiring mechanics and IT professionals assess male and female applicants differently?

2. Through what mechanisms at the recruiter, job, company and country levels can gender discrimination in hiring be explained?

Our empirical analyses draw on data stemming from the Employer Survey (WP7) of the NEGOTIATE project (Imdorf et al. 2019). The Employer Survey consists of an internationally comparative factorial survey experiment and overcomes previous difficulties in measuring discrimination across national contexts (Quillian et al. 2019). Real job advertisements were sampled in Bulgaria (BG), Greece (GR), Norway (NO), and Switzerland (CH). The remainder of this article is structured as follows. First, we describe mechanisms of gender discrimination in hiring and contextual factors explaining variation therein. Thereafter, we describe the research design, data, and the methods applied. Subsequently we present and discuss the empirical findings. In the last part, we summarise our findings and conclude the article with a discussion.

2 Mechanisms of Gender Discrimination in Hiring

2.1 Economic Theories and Research Strategies to Study Gender Discrimination in Hiring

Sociological analysis of gender discrimination in hiring and its methodology have developed considerably since the early proposition of two general types of labour market discrimination models advanced by neoclassical economists: Gary Becker’s (1957) taste-for-discrimination model and the model of statistical discrimination (Arrow 1973; Phelps 1972). Becker assumes that employers, fellow workers or customers aim for a certain profile regarding candidates’ social and psychological characteristics and seek to avoid members of certain groups—for example, men who feel uncomfortable being supervised by women. The model of statistical discrimination proposes that employers use either valid information or stereotypes about average group characteristics in order to reduce asymmetric information and predict individual worker ability and productivity—for example, assuming women and mothers to be absent from the workplace more often owing to family duties.

Guryan and Charles (2013) point out that, after an initial debate in the 1970s and 1980s about whether one of the two models better described (gender) discrimination, the literature has only recently returned to the question of whether taste-based or statistical discrimination is a more appropriate description of the phenomenon of discrimination. These more contemporary analyses of discrimination differ from the early neoclassical approaches both in their definition and in their measurement of discrimination (Keuschnigg and Wolbring 2016). Economists initially defined discrimination as a difference in earnings between two groups of workers of equal productivity—the gender gap in wages, for instance—and applied regression-based methods to prove their theoretical assumptions. But such regression-based approaches have been criticized for their limited ability to isolate the portion of economic inequality that may be ascribed to discrimination (Guryan and Charles 2013).

This criticism has initiated a shift to alternative methods, particularly field experiments and measurements of discrimination. Two common methods shall be briefly mentioned: first, in-person audit studies, in which actors are sent to job interviews pretending to be candidates (see, for instance, Neumark et al. 1996; who found evidence of discrimination against women applying to be waiting staff in high-priced restaurants in the USA). Second, correspondence tests, where a set of fictitious resumés is sent to real job openings, with call-back rates being the dependent variable (e.g. Riach and Rich 2006 for a British study that found significant discrimination against men in “female occupations” and against women in “male occupations”; for an extensive list of recent correspondence experiments, see Baert 2018). Use of these two designs has shifted the focus of analysis from the worker’s economic outcome to the employer’s behaviour (Guryan and Charles 2013). Discrimination is now measured as differences in hiring behaviour.

Field experiments allow researchers to test more precisely specific assumptions by either the taste-based discrimination or the statistical discrimination model (see, for example, Weichselbaumer 2004). However, Keuschnigg and Wolbring (2016) argue that neither correspondence tests nor in-person audits manage to identify causal mechanisms behind discriminatory behaviour. While field experiments enable the measurement of discrimination in employment, they can hardly explain why employers discriminate based on gender, ethnicity or age (Imdorf 2017). Moreover, those methods can pose serious ethical concerns (Keuschnigg and Wolbring 2016, p. 190).

In contrast, factorial survey experiments (FSEs, or vignette studies), bypass such ethical concerns, and allow for simultaneously testing key assumptions underlying different models of discrimination. They constitute multidimensional experimental designs that implement vignettes representing hypothetical objects or situations (Auspurg and Hinz 2015). FSEs have been used in labour market research to gain knowledge about both recruiters’ and job seekers’ behaviour (Abraham et al. 2013; Van Belle et al. 2018). In the respective applications, recruiters receive brief descriptions of fictitious job applicants that vary with regard to specific attributes, and they are asked if they would consider hiring such a person. The experimental manipulation of the stimuli presented to the respondents allows researchers to combine several dimensions of candidates’ characteristics in an orthogonal design. Accordingly, the major advantage of such a design is its high internal validity, as the vignette characteristics do not correlate with each other. So far, only a few studies have applied FSEs in dissecting the mechanisms of gender discrimination when employers hire. Kübler et al. (2018) have found that the degree of discrimination against women is the lower the higher the share of women in an occupation. At the same time, men may also experience discrimination in female-dominated occupations (Birkelund et al. 2019).

2.2 Sociological Perspectives on Gender Discrimination in Hiring

Economic analysis has made extensive use of the models of taste-based discrimination and statistical discrimination. However, both concepts are limited as long as they reduce employers’ decisions to assumptions about job candidates’ individual ability and productivity. Models that assume that taste-based or statistical discrimination helps to maximise companies’ productivity neglect the complexity of social coordination and dependencies in the workplace that frame a company’s productivity too (Imdorf 2017). Sociological reasoning facilitates the understanding of “collective models of discrimination”, where “groups act collectively against each other” (Autor 2008, p. 2). From this perspective, productivity can be seen “as the outcome of social relations at the workplace, rather than solely the outcome of workers’ skills” (Shih 2002, p. 102). Collective mechanisms can be assumed in situations in which the recruiter wants to ensure that the prospective employee will be an integral part of the work group. At the core of this exclusionary organisational process is the need for the “social fit” of job candidates. For instance, a candidate’s presumed ability to integrate into a work organisation dominated by one sex may be perceived conditional on that person’s sex (Bygren and Kumlin 2005). A qualitative study in the male-dominated Swiss automotive occupational field indicates that employers may refrain from hiring female apprentices as they fear that young women may distract the predominantly male workforce (Imdorf 2013). Kricheli-Katz (2019) finds evidence that women’s entrance into high-status occupations poses a threat to the identity and interests of high-occupational-status men. In fact, Becker’s (1957) model of taste-based discrimination, whereby an employer must pay a wage premium to men in order to win them to work in a gender-integrated setting, may be compatible with the assumption that employers respond to the interests of male employees when they exclude women from their job categories in the hiring process (Bielby and Baron 1986). Taken together, we can expect that in the two male-dominated occupations under study, female applicants are rated less positively than male applicants. Our first hypothesis thus reads as follows: female candidates in the occupational fields of mechanics and IT professionals have lower recruitment chances than male candidates (H1).

3 Contextual Factors Explaining Gender Discrimination in Hiring

Bielby and Baron (1986) assume a variation across jobs and establishments in the desire and ability of male workers to exclude women given the diversity of organisational and technical arrangements. Similarly, Reskin (2003) proposes that prejudices and stereotypes only unfold if organisational contexts and practices allow for it. It is therefore of interest to better understand under which conditions discriminatory preferences translate into unequal treatment (Keuschnigg and Wolbring 2016). These conditional contexts are located at various levels, such as recruiter, vacancy, company, occupation, or country. In the following section, we sketch a number of relevant opportunity structures for gender discrimination at different levels.

3.1 Recruiter, Job and Company Characteristics

At the recruiter level, Cole et al. (2004) have analysed whether recruiters’ and applicants’ gender influence recruiters’ judgments regarding applicants’ resumés, which reflects a form of taste-based discrimination. They found that female recruiters perceived male resumés to report more work experience than female resumés, whereas male recruiters perceived female applicants as having more extracurricular interests than male applicants. Gorman (2005) analysed hiring processes in large US law firms and found evidence that organisational decision makers favour candidates of their own gender. Generally, female decision makers fill more vacancies with women than do male decision makers. Kricheli-Katz (2019) finds that female managers value female job candidates more highly than male managers when hiring for previously male-dominated high-status occupations. Hence, gender discrimination patterns may differ according to the recruiters’ own gender.

At the job level, multiple characteristics of a vacancy may influence gender discrimination in hiring. Statistical discrimination may increase with a higher requirement of work experience, a job criterion that can be used as a gendered sorting mechanism (Ranson and Reeves 1996). As the authors show, female candidates are more likely to be accepted for computer professional jobs that do not require much work experience. Economic job dimensions include the importance of filling a vacancy, the salary of the position and the job status (in terms of authority and/or seniority). Women are often discriminated against in the hiring for senior or high-wage positions (Fernandez and Mors 2008; Riach and Rich 2006; Petit 2007; Yavorsky 2019). On the one hand, hiring for jobs with higher costs increases the degree of risk aversion on the recruiter’s side, with risk-averse employers being more prone to activating stereotypes (Reskin and Branch McBrier 2000). On the other hand, women may have better chances of being recruited for part-time positions, as such jobs are viewed as being most compatible with (future) motherhood (Herman et al. 2013; Pedulla 2016). In accordance with neoclassical economic assumptions, jobs with flexible schedules may decrease gender discrimination in hiring, as they are accompanied by presumed lower indirect labour costs of mother workers (e.g., in view of anticipated absence owing to parental duties; see Anker 1997). In particular, jobs that allow for home-office work may reduce the organisational opportunity structure for discrimination in hiring (for a critical account, see Van Echtelt et al. 2009).

With regard to the company’s characteristics, previous research concerning the size of the company are inconclusive. On the one hand, Bygren and Kumlin (2005) find evidence that large work organisations tend to make more gender-neutral recruitments. On the other hand, Baert et al. (2018), in an experimental study of gender discrimination in hiring for higher skilled occupations in Belgium, did not find any evidence of a link between firm size and discrimination. However, their study does provide suggestive evidence that discrimination may be lower in public and non-profit organisations than in for-profit organisations. As far as the firms’ economic performance is concerned, they find no association between the economic well-being of the company and recruiters’ tendency to discriminate. One could, however, assume that recruiters are more risk averse and therefore more prone to statistically discriminating when they hire under difficult economic conditions (Baert et al. 2015). Taken together, we can formulate the more general assumption, that gender discrimination varies with recruiter, vacancy- and company-specific opportunity structures (H2).

3.2 Occupation and Country Characteristics

Further opportunity structures for gender discrimination in hiring can be assumed to exist on more aggregate levels, such as the occupational field and the country. With regard to the occupational field, diverse research has shown that the degree of gender discrimination and the mechanisms behind it are heterogeneous and vary with occupational characteristics (Baert 2018; Petit 2007). A fundamental characteristic underlying gender discrimination is the gender ratio within an occupation. Discrimination against candidates of one gender has been found to occur in occupations dominated by the other gender (for women: Kübler et al. 2018; for men: Glick et al. 1988; Weichselbaumer 2004). The proportion of women in the occupational field of mechanics is smaller than that for IT professionals (see below), suggesting a higher potential for gender discrimination in the former field.

Glick et al. (1988), in correspondence with Goffman’s (1977) account of institutional genderism, have argued that gender discrimination is influenced by occupational stereotypes within each occupational field to different degrees. Indeed, Gorman’s (2005) findings show that when selection criteria include a greater number of gender stereotypes, candidates of the opposite gender constitute a smaller proportion of new hires. With respect to more objective occupational job requirements such as heavy lifting and/or other physical efforts, the work of mechanics may be associated with higher physical (muscular) strength than IT work, disqualifying women from the former in the eyes of recruiters more than from the latter (Anker 1997). As Imdorf (2013) shows, physical strength can still be a criterion for hiring apprentices in mechanics in Switzerland. IT, in contrast, includes a variety of quite diverse jobs, with some of them requiring considerable soft and communicative skills, which are in line with female stereotypes (Barone 2011). Moreover, work in IT can—at least partly—be carried out at home. IT work may thus offer greater flexibility both with regard to the time schedule and place than mechanics. Taken together, the different opportunity for flexibility, as well as the different physical and social skill requirements and respective gender stereotypes in the two occupational fields, may result in a higher tendency of risk-averse recruiters to discriminate against women in the field of mechanics than in the IT sector. Overall, we can thus assume gender discrimination in hiring to be stronger in the occupational field of mechanics than in the field of information technology (H3).

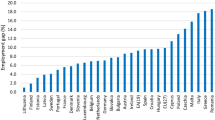

We expect H3 to be valid in all four countries under investigation. In Norway, horizontal gender segregation has been stable for the last two decades (Barth et al. 2014). Both IT (74% males), and even more so mechanics (93% males), are solidly male-dominated occupations (NAV Statistics 2019). In Switzerland, too, the female work force in IT (22%) is larger than that among mechanics (13%, BfS 2019). In Bulgaria, female representation in the field of mechanics (25%) and IT (27%; Eurostat 2018; National Statistical Institute 2019) is somewhat higher. However, women’s disadvantage with regard to IT positions becomes substantial after they have become mothers (Stoilova 2008). In the Greek labour market, vertical and horizontal gender segregation have only slightly declined (Dermanakis 2005; Kantaraki et al. 2008). In IT, women account for about 11% of the workforce (European Commission 2019); in the field of mechanics, the share is between 8 and 11% (ELSTAT 2019). These figures are broadly in line with the estimated percentages of female workers in both occupational fields yielded in an expert survey in the four countries, conducted during the NEGOTIATE project, which we introduce below.

Nevertheless, the level of occupational gender discrimination in hiring is likely to vary among the four countries, which constitute different configurations of national characteristics such as the economy, educational and gender equality policies, and gender norms. These contextual characteristics, too, may constitute opportunity structures for gender discrimination in hiring. Economic conditions affect recruiters’ hiring behaviour through labour market tightness (i.e. a shortage of qualified candidates) and youth unemployment. Both less (Baert et al. 2015) and more (Mooi-Reci and Ganzeboom 2015) gender discrimination have been reported in occupations characterised by tight labour market conditions. With regard to the educational system, training for IT jobs predominantly takes place in institutions of higher education, whereas training for mechanics is usually organised at the upper-secondary level of vocational education and training (VET). Either VET can be solely school based (as in Greece or Bulgaria) or it also takes place in companies (dual VET, as in Norway and Switzerland). Where training is more employer oriented and standardised, VET certificates signal occupational skills more reliably. Hence, recruiters’ assumptions about applicants’ skills should be less based on gender stereotypes in the latter two than in the former two countries.

Policies promoting gender equality, such as antidiscrimination policies, may prevent discriminatory behaviour. Implementing antidiscrimination policies (e.g., through ombudspersons) reduces opportunities for discriminatory behaviour in hiring and facilitates the documentation and processing of such behaviour (Teigen 1999; Peterson and Saporta 2004). These measures are particularly well-developed in Scandinavian countries, which in our case concerns Norway. Countries that promote gender equality by means of paid parental leave and publicly financed childcare infrastructure have a higher female and maternal labour market participation rate (Leitner 2003). These policies often also reflect gender norms. Where mothers are more integrated into the labour market, such as in Norway and Bulgaria, it can be argued that employers are less risk-averse to hiring women.

Overall, we can thus formulate the tentative assumption that gender discrimination against female applicants may be stronger in Bulgaria and Greece than in Switzerland and especially in Norway. However, as educational and social policies as well as economic and cultural contexts might be intertwined, four countries are far too few to test any cross-national hypotheses properly.

4 Data and Method

4.1 Data and Sample

Our data were obtained in the context of the Horizon 2020-funded project “NEGOTIATE—Overcoming early job-insecurity in Europe”Footnote 1. Within this project, a multinational online recruiter survey was conducted in Bulgaria, Greece, Norway and Switzerland across five occupational fields (mechanics, finance, nursing, gastronomy and information technology).Footnote 2 The study participants (recruiters) were sampled through real-world vacancies, which affords the study a very high external validity. To ensure that our fictional candidates adequately fit into the profiles of the vacancies across countries, the latter were sampled according to job titles based on selected four-digit ISCO-08 codes.Footnote 3 During a period of six weeks in spring 2016, open jobs were sampled in the four countries through online job portals, official labour office websites, and companies’ own websites. The recruiters in charge of the 12,147 vacancies sampled were contacted. In total, 2,885 recruiters have participated in the survey (NEGOTIATE 2020).

4.2 Study Design

The survey consisted of multiple parts. On the one hand, a vignette study (FSE) was implemented. Each recruiter was presented with ten hypothetical CVs of skilled young workers (eight in the case of Greece), and asked to rate them according to the likelihood of being considered for the sampled vacancy. The vignette was displayed graphically, with the CV built into a timeline (for an example in German, see Fig. A.1 in the Online Appendix). A total of 20,634 vignettes were assessed by recruiters. On the other hand, in a standard survey mode, recruiters were asked about characteristics with regard to the vacancy, the company and themselves.

The vignettes used in the study, representing the fictitious CVs of job candidates, were designed to vary in four dimensions: unemployment duration and timing of unemployment (seven categories), educational and professional trajectories (nine categories), gender (male, female), and a dichotomous nation-specific experimental variable. Nationality (in each country: being a native and belonging to the ethnic majority) and time since leaving formal education (a total of five years, during all of which the candidate was available to the labour market) were held constant in the experiment. This yields a vignette universe of 252 (7*9*2*2) possible combinations. Implausible combinations of unemployment histories and career trajectories were excluded from the vignette universe, as they led to irritation, as two pre-tests have shown. Hence, the design is not perfectly orthogonal (for a correlation matrix see Table A.4 in the Online Appendix).

Based on response rate estimates derived from the pre-tests, a D-efficient sample (Auspurg and Hinz 2015) of 162 (CH and NO) and 90 (BG and GR) different vignettes was drawn and allocated, for each country separately, to 10 (BG, GR) and 18 (CH, NO) vignette decks with eight (GR) and ten (BG, CH, NO) vignettes each.Footnote 4 Randomisation of the vignettes into decks was conducted in order to maximise D‑efficiency (for a calculation of D‑efficiency for the various options, see Table A.5. in the Online Appendix). The respective vignette decks were allocated to the recruiters through randomisation (NEGOTIATE 2020).

4.3 Dependent Variable and Analytical Strategy

Recruiters were asked to rate each of the hypothetical CVs. The exact wording was “How likely is it that you would consider a person with the resumé displayed above for the advertised job?” The answering scale ranges from 0 (“practically zero”) to 10 (“excellent”). It was further transformed by adding “1”, and then logged in order to remove skewness.Footnote 5 In the following, we rely on these transformed ratings (ranging from 0 to 2.4) as our dependent variable. We apply multilevel linear models (Maas and Hox 2005; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2012) with vignettes (first-level units) nested in vacancies (second-level units). Because the vacancies were sampled for each of the five occupations separately in the NEGOTIATE project, the data set technically consists of 20 separate vignette experiments. We thus decided to estimate eight separate models: one for each country (BG, CH, GR, NO) and occupational field (mechanics, IT).

To test our hypotheses, we conduct our analyses in two steps. In a first step, we assess “raw” gender discrimination as the coefficient of vignette gender on recruitment chances (controlling only for candidate characteristics, Table 1). By comparing coefficients across models, we test for differences in gender discrimination between countries and occupations (see Table A.6 in the Online Appendix). In a second step, we include interaction terms between vignette gender and the various opportunity structures at the recruiter, vacancy and company levels (see Table 2). This measure allows us to figure out whether recruiters’ “tastes” or preferences are generally applicable or whether they are held against male or female candidates in specific contexts. As interaction terms are not straightforward to interpret, we present them as average marginal effects (AMEs) (Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). For the sake of brevity, we limit their graphical illustration to significant interaction terms.

4.4 Operationalisation of the Independent Variables

The focus of this study is on the effect of the vignette’s gender. Five further variables were controlled. They include a vignette’s unemployment duration (none, 10 months, 20 months) and educational level (secondary, upper secondary, tertiary). Moreover, we include three dummy variables that were constructed to measure the vertical and horizontal match between the vignette and the requirements of the vacancy. Vertical match was measured as a dummy variable (1: candidate’s educational level matches job requirements, 0: under- or over-qualified). Horizontal match was measured with two dummy variables representing two stages, namely (1) the fit of the candidate’s educational specialisation with the vacancy (1: obtained in the respective occupation) and (2) the fit of the candidate’s work experience (1: obtained in the respective occupational field). We also include an interaction term between these two dummy variables.

Our data are structured in a hierarchical way. Recruiters were approached through sampled real-life vacancies. The sample was restricted to one vacancy and recruiter per company. Hence, the levels of vacancy, recruiter and company overlap. We thus have a two-level structure (candidates nested in recruiters/vacancies/companies). Regarding recruiters’ “tastes”, we measure the candidate’s fit into the team as a hiring criterion (0: not important to 4: very important), recruiters’ unemployment resentment (no, it depends, yes) as well as recruiters’ gender (1: male). We further include variables that comprise specific features of the vacancy such as whether the vacancy was already filled (1: yes), the importance of filling the vacancy (1: not important to 4: very important), the recruiter’s perceived difficulty in filling the vacancy (1: very easy to 4: very difficult), the necessity of work experience for the vacancy (many years, some years, not necessary), the status of the advertised job in the company hierarchy (trainee, employee, executive function), the wage of the advertised position (measured in country- and occupation-specific quartiles), and whether the advertised position is full time or part time (1: part time). Finally, we include variables that describe the organisational structure of the company, including firm size and economic performance. For the latter, recruiters were asked to compare their company’s current economic performance with the economic performance in the previous year (answering categories: improved, stable, worsened, non-profit oriented). To avoid methodological effects, we include two dummy variables as controls that pertain to the order of appearance (primacy, 1: first or second vignette shown) and its deliberate selection into the deck (“fixed vignette”, which was included to exhibit a good fit with the real-world vacancy).

5 Findings

5.1 Gender Discrimination

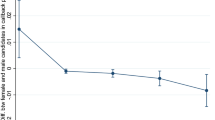

Figure 1 illustrates the AME for vignette gender (female) on hiring chances across the four countries and two occupations (for coefficients see Table 1). As the bars indicate, female candidates have a lower likelihood of being hired in three countries. In Bulgaria, female candidates for a vacancy in mechanics are rated about 43% (b = −0.432***)Footnote 6 less positively than their otherwise comparable (ceteris paribus) male competitors. In Greece, female candidates for a vacancy in mechanics are rated about 18% less positively, in Switzerland and Bulgaria, female candidates for vacancies in IT are rated about 5% less positively. No gender discrimination in recruiters’ ratings can be observed in Norway.

The coefficients for vignette gender in mechanics significantly differ between the countries, with the exception of the comparison between Switzerland and Norway. The coefficients for the occupational field of IT do not significantly differ between the countries (see Table A.6 for respective test statistics). Our data thus only partly support our first hypothesis (H1). Rather, it seems that (the extent of) gender discrimination depends on national and occupational contexts.

The results also only partly confirm our assumption that the extent of gender discrimination is greater in mechanics than in IT (H3). Although our findings indicate stronger discrimination in mechanics versus IT for both Greece and Bulgaria, the difference between the coefficients is only significant in Bulgaria. Finally, the effects of the control variables (see Table 1) highlight the crucial relevance of vertical and horizontal match in all four countries, a finding in line with previous research (Shi et al. 2018).

5.2 Gender-Relevant Effects of Opportunity Structures

This section explores how higher level factors influence gendered hiring decisions. Based on the ideas of Reskin (2003) and Peterson and Saporta (2004), we assume that gender discrimination is contingent upon opportunity structures (H2). We test this second hypothesis by estimating interaction terms between the vignette’s gender and such factors at the recruiter, job and company levels. For ease of interpretability, the results are depicted as average marginal effects (AMEs, Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6), limited to the significant effects. The AMEs were obtained under the control of other vignette characteristics, but not controlling for the respective other opportunity structures. To check the robustness of our results, all gender-specific mechanisms were also estimated simultaneously in one model (see Table 2).

Regarding the need for work experience (Fig. 2), we find evidence of female candidates being more critically scrutinised than male candidates if (some) work experience is required (as, for instance, in Switzerland in IT). Here, recruiters may use work experience as a gendered sorting mechanism (Ranson and Reeves 1996). In contrast, in Bulgaria (both occupations) and Greece (mechanics), women are discriminated against if no previous work experience is required. As VET is school based in these countries, recruiters’ risk aversion may play a role. Applicants who need on-the-job training require employers to make a financial commitment, and (potential) motherhood could diminish the returns on these investments.

Gender discrimination over the need for job experience. Separate models for each occupation in each country. Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals for interaction effects between vignette gender and opportunity structure, controlling for candidate characteristics in Table 1. Only figures for significant interaction terms are presented. For coefficients see Table A.3 in the Online-Appendix

Next, we turn to the position in the company’s hierarchy a successful applicant would occupy (Fig. 3). In many contexts, female candidates for trainee or employee positions receive lower ratings than their otherwise comparable male competitors (as for mechanics in Bulgaria and Greece, IT employees in Bulgaria and Switzerland and trainees in mechanics in Norway). What becomes clear, however, is that female candidates seem to “lose” their gender disadvantage in the hiring for executive positions—with the exception of IT in Greece. Qualities that are interpreted as typically feminine, such as communications skills, may be useful for ascending the ladder in a male-dominated professional environment such as IT (see also Major et al. 2007). This model is particularly striking in Norway, where, even when controlling for a position’s wages, female candidates appear to be actively promoted (see Table 2).

Gender discrimination according to job status. Separate models for each occupation in each country. Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals for interaction effects between vignette gender and opportunity structure, controlling for candidate characteristics in Table 1. Only figures for significant interaction terms are presented. For coefficients, see Table A.3 in the Online Appendix

Regarding wages (Fig. 4)—in line with our assumptions and the theoretical idea of risk aversion (Reskin and Branch McBrier 2000)—we find evidence that female candidates may be discriminated against in higher paying jobs in IT in Switzerland. In Bulgaria, women are discriminated against across all wage groups in the field of mechanics. Another pattern runs against our expectations. Contrary to our assumption that lower-paid jobs (particularly in IT) would offer some flexibility and be preferentially given to women (and future mothers), we observe that recruiters hiring for such jobs in Greece and Bulgaria discriminate more strongly against female applicants than those hiring for higher-paid jobs. This result is, however, in line with Yavorsky’s (2019) finding that women are more likely to be discriminated against in manual jobs than in academic jobs.

Gender discrimination according to wage quartiles of the vacancy. Separate models for each occupation in each country. Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals for interaction effects between vignette gender and opportunity structure, controlling for candidate characteristics in Table 1. Only figures for significant interaction terms are presented.. For coefficients see Table A.3 in the Online Appendix

Figure 5 displays the effects of gendered recruitment decisions on full-time and part-time positions. According to our theoretical expectations, part-time positions would be more likely to be filled with female candidates. For the most part, however, part-time status does not seem to influence hiring decisions in favour of female candidates. Nevertheless, we do find evidence that gender discrimination is more likely in the hiring for full-time positions (as is the case for mechanics in Greece and Bulgaria and IT professionals in Bulgaria and Switzerland).

Gender discrimination according to full-time and part-time work. Separate models for each occupation in each country. Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals for interaction effects between vignette gender and opportunity structure, controlling for candidate characteristics in Table 1. Only figures for significant interaction terms are presented. For coefficients see Table A.3 in the Online Appendix

With regard to company characteristics, we turn to the company’s economic performance (Fig. 6). In line with our expectations, we find that female applicants are discriminated against if the company’s economic performance has worsened (as is the case for IT professionals in Bulgaria and Norway and for mechanics in Bulgaria). However, we also find evidence for discrimination of female candidates in non-profit companies, as is the case for mechanics’ jobs in Norway and Greece. Finally, if the company’s economic performance has remained stable, in Greece and Bulgaria, female candidates are less likely to be hired for mechanics’ jobs, whereas in Norway they are more likely to be hired for the same jobs.

Gender discrimination according to economic performance of the company. Separate models for each occupation in each country. Average marginal effects with 95% confidence intervals for interaction effects between vignette gender and opportunity structure, controlling for candidate characteristics in Table 1. Only figures for significant interaction terms are presented.. For coefficients see Table A.3 in the Online Appendix

In sum, our findings partly confirm our second hypothesis (H2), from which we assumed that the degree of gender discrimination in hiring is moderated by recruiter-, vacancy- and company-specific structures. Contrary to H2, we do not find evidence that recruiter characteristics such as recruiters’ gender or unemployment resentments moderate gender discrimination in hiring for skilled jobs, nor do we find conclusive evidence that either company size, the importance of or difficulty in filling the vacancy, or the organisational prerequisite of social fit, have an impact. We thus observe several, sometimes ambivalent, patterns.

6 Summary and Conclusion

Research has repeatedly documented women’s impeded access to STEM occupations and indicated gender discrimination in hiring for male-dominated occupations. This article highlights that gender discrimination in hiring for two male-dominated jobs varies between countries and occupations and depends on specific opportunity structures at the job and company levels. Applying one of the first internationally comparative factorial surveys in the field of hiring discrimination, our results strengthen Quillian et al.’s (2019) recent finding that patterns of discrimination vary across country contexts. Our results further support sociological claims that prejudices and/or stereotypes can only be upheld if organisational contexts and practices allow for it (Reskin 2003) or if there is an opportunity structure for discrimination (Peterson and Saporta 2004).

Overall, we find that female applicants have lower recruitment chances compared with their male counterparts, but this phenomenon is not equally pronounced in all contexts. As our results have shown, the degree of discrimination against female candidates not only varies between countries, but also between occupations within countries. The strongest gender discrimination was found in Bulgaria in the field of mechanics, followed by Greece in the field of mechanics, and Greece and Switzerland in the field of IT. No discriminatory behaviour against female candidates was found in Norway, which is in line with Birkelund et al. (2019).

With regard to country differences, our findings confirm the assumption that gender discrimination is higher in Bulgaria and Greece than in Switzerland and Norway. Owing to low case numbers at the country level, however, we cannot disentangle the specific relevance of different country-level factors. We can only assume that the absence of gender discrimination in Norway is due to its distinctive gender equity and anti-discrimination policies combined with employers’ trust in the educational signals of skilled workers. The absence of gender discrimination in the field of mechanics in Switzerland may be facilitated by its highly standardised dual-VET system, which prevents recruiters from using gender as an indication of occupational skills, whereas in IT, where training is for the most part organised at the tertiary level, gender stereotypes still seem to apply. In contrast to Switzerland, gender discrimination seems to be stronger in the field of mechanics than in information technology in Bulgaria and Greece. In those two country contexts, where the signals of vocational certificates are less reliable gender stereotypes can become salient in anticipating occupational skills. Recruiters may assume that the more flexible IT jobs are more accessible for skilled women, whereas jobs in mechanics tend to be full time, with little room for temporal and spatial flexibilisation in manufacturing companies. Supposing further gender stereotypes with regard to the physical and social skill requirements of the two occupations, recruiters may be more risk averse about female candidates when hiring mechanics than when hiring IT professionals.

We have further explored various mechanisms at the recruiter, vacancy and company levels that may mediate gender discrimination. Our analyses revealed a number of economic mechanisms (representing opportunity structures for gender discrimination at the levels of the vacancy and of the company), whose influence on employment chances depends on the gender of the applicant. These mechanisms apply to work experience required, job status, wages, full-time or part-time work, and the economic performance of the company, as well as its economic orientation (i.e. public versus private). Recruiters’ characteristics, on the other hand, have not shown such gender-specific effects. The direction and significance of these gender-specific opportunity structures remain multifaceted and sometimes ambivalent. Our findings indicate that such mechanisms have a different impact, or even take different directions, depending on the occupational and country context (for a summary, see Table 3).

Overall, our findings suggest that the mechanisms underlying gender discrimination might be multifaceted and highly contextual. Not only do they depend on opportunity structures and gender-specific occupational stereotypes or skill expectations, these mechanisms further vary substantially between countries and occupations. Future research should thus both theorise and measure these mechanisms in a differentiated way and consider that the salience of these mechanisms may vary on several contextual levels. The practical implication of our overall finding is that, to be both effective and economical, anti-gender discrimination policy must be target-orientated to occupational contexts where there is scope for discriminatory practices in hiring. As such, an in-depth understanding of the discriminatory mechanisms is exigent. The mechanisms of gender discrimination in the hiring for skilled jobs for which we have found evidence (Table 3) lend support to the model of statistical discrimination rather than to the model of taste-based discrimination. Even though we sometimes identify diverging patterns, a number of findings point to economic risk aversion by recruiters in hiring IT professionals and mechanics. For instance, when the hiring is related to certain direct costs (e.g. higher wages, worsening economic performance), or to indirect training-related costs and insecure returns (e.g. trainee positions, unskilled and low-wage jobs, particularly in countries with less established VET), female candidates are passed over for male candidates.

Our study has several limitations: it is confined to the analysis of two male-dominated occupations, and our results need further validation with regard to other STEM occupations. Moreover, the occupation- and country-specific mechanisms we have discussed might not hold for female-dominated or gender-neutral professions. We also need to be aware that most of the resumés in the vignette experiment showed a rather “bad fit” with the requirements of the sampled jobs. It would be preferable to apply the factorial survey methodology in the study of gender discrimination in hiring with less interference from competing research aims, and to use the remaining vignette dimensions to directly address theory-driven discrimination mechanisms. Finally, we still need a better understanding of how we can explain statistical gender discrimination effects with opportunity structures. Beside the replication of our occupational and international comparative results, several more ambivalent findings warrant greater scrutiny.

Notes

A scientific use file of the NEGOTIATE employer survey data is available through the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD) at https://doi.org/10.18712/NSD-NSD2644-V1.

The ISCO codes used were 7230 and 7233 for Mechanics, and 2511–2513, as well as 2521–2523 for IT professionals.

Although ten decks à ten vignettes were planned for Greece, only eight vignettes were shown in the survey due to technical implementation issues (for more information see NEGOTIATE 2020).

Given the experimental design, which is aimed at maximum variation, most vignettes in a deck exhibit only a poor fit with the advertised job. Thus, the distribution of the ratings on the original scale (0–10) is right-skewed.

Since the dependent variable was logged, it can be interpreted as the percentage change in the recruiter’s rating with a one-unit change, i.e. the difference between female and male applicants, in the independent variable.

References

Abraham, Martin, Katrin Auspurg, Sebastian Bähr, Corinna Frodermann, Stefanie Gundert, and Thomas Hinz. 2013. Unemployment and willingness to accept job offers: Results of a factorial survey experiment. Journal for Labour Market Research 46:283–305.

Anker, Richard. 1997. Theories of occupational segregation by sex: An overview. International Labour Review 136:315–339.

Arrow, Kenneth. 1973. The Theory of Discrimination. In Discrimination in Labor Market, eds. Orley Ashenfelter and Albert Rees, 3–33. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Auspurg, Katrin, and Thomas Hinz. 2015. Factorial Survey Experiments. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Autor, David. 2008. The Economics of Discrimination I. Lecture Note. Massachusetts. MIT. 14.663.

Baert, Stijn. 2018. Hiring Discrimination: An Overview of (Almost) All Correspondence Experiments since 2005. In Audit Studies: Behind the Scenes with Theory, Method, and Nuance. Methodos Series (Methodological Prospects in the Social Sciences), Vol 14. Ed. Michael S. Gaddis. Cham: Springer.

Baert, Stijn, Bart Cockx, Niels Gheyle and Cora Vandamme. 2015. Is There Less Discrimination in Occupations Where Recruitment Is Difficult? Industrial and Labor Market Review 68:467–500.

Baert, Stijn, Ann-Sofie De Meyer, Yentl Moerman and Eddy Omey. 2018. Does size matter? Hiring discrimination and firm size. Journal of Manpower 39:550–566.

Barone, Carlo. 2011. Some Things Never Change: Gender Segregation in Higher Education across Eight Nations and Three Decades. Sociology of Education 84:157–176.

Barth, Erling, Inel Hardoy, Pal Schøne and Kjersti M. Østbakken. 2014. Hva betyr høy yrkesdeltakelse for kjønnssegregering? [What does high labour market participation mean for gender segregation?]. In Kjønnsdeling og etniske skiller på arbeidsmarkedet, eds. Liza Reisel and Mari Teigen. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

Becker, Gary S. 1957. The Economics of Discrimination. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Van Belle, Eva, Valentina Di Stasio, Ralf Caers, Marijke De Couck and Stijn Baert. 2018. Why Are Employers Put Off by Long Spells of Unemployment? European Sociological Review 34:1–17.

BfS, Bundesamt für Statistik. 2019. Beschäftigte nach Wirtschaftsabteilungen und Geschlecht. https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kataloge-datenbanken/tabellen.assetdetail.8167804.html (Accessed: 24 June 2019).

Bielby, William T., and James N. Baron. 1986. Men and Women at Work: Sex Segregation and Statistical Discrimination. American Journal of Sociology 91:759–799.

Birkelund, Gunn E., Avra Janz and Edvard Nergård Larsen. 2019. Do males experience hiring discrimination in female-dominated occupations? An overview of field experiments since 1996. GEMM Working Paper. Retrieved from: http://gemm2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Gender-Discrimination-a-summary-1.pdf (Accessed: 29 May 2019).

Blickenstaff, Jacob C. 2005. Women and science careers: Leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gender and Education 17: 369–86.

Bygren, Magnus, and Johanna Kumlin. 2005. Mechanisms of Organizational Sex Segregation: Organizational Characteristics and the Sex of Newly Recruited Employees. Work and Occupations 32:39–65.

Charles, Maria. 2003. Deciphering sex segregation: vertical and horizontal inequalities in ten national labour markets. Acta Sociologica 46:267–287.

Cole, Michael S., Hubert S. Field and William F. Giles. 2004. Interaction of Recruiter and Applicant Gender in Resume Evaluation: A Field Study. Sex Roles 51:597–608.

Dermanakis, Nikos E. 2005. The horizontal-occupational segregation in the Greek labour market. Research Centre for Gender Equality. Statistical Bulletin 3.

DiPrete, Thomas A., and Claudia Buchmann. 2013. The rise of women: The growing gender gap in education and what it means for American schools. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Van Echtelt, Patricia, Arie Glebbeek, Suzan Lewis and Siegwart Lindenberg. 2009. Post-Fordist Work: A Man’s World? Gender and Working Overtime in the Netherlands. Gender & Society 32:188–214.

ELSTAT, Hellenic Statistical Authority. 2019. Labour Force Survey—annual data. http://nsi.bg/en/content/15277/%D0%BC%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BD%D0%B8/labour-force-survey-annual-data (Accessed: 9 July 2019).

England, Paula. 2010. The Gender Revolution Uneven and Stalled. Gender & Society 24:149–66.

European Commission. 2019. Women in Digital Scoreboard 2019—Greece. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/women-digital-scoreboard-2019-country-reports (Accessed: 23 June 2019)

Eurostat. 2018. Employed ICT specialists by sex, http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=isoc_sks_itsps&lang=en (Accessed: 18 June 2019).

Fernandez, Roberto M., and Marie Louise Mors. 2008. Competing for jobs: Labor queues and gender sorting in the hiring process. Social Science Research 37:1061–1080.

Glick, Peter, Cari Zion and Cynthia Nelson. 1988. What mediates sex discrimination in hiring decisions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55:178–186.

Goffman, Erving. 1977. The arrangement between the sexes. Theory and Society 4:301–311.

Gorman, Elizabeth H. 2005. Gender Stereotypes, Same-Gender Preferences, and Organizational Variation in the Hiring of Women: Evidence from Law Firms. American Sociological Review 70:702–728.

Guryan, Jonathan, and Kerwin Kofi Charles. 2013. Taste-based or Statistical Discrimination: The Economics of Discrimination Returns to its Roots. The Economic Journal 123:417–432.

Hakim, Catherine. 1996. The sexual division of labour and women’s heterogeneity. British Journal of Sociology 47:178–188.

Herman, Clem, Suzanne Lewis and Anne Laure Humbert. 2013. Women Scientists and Engineers in European Companies: Putting Motherhood under the Microscope. Gender, Work and Organization 20:467–479.

Imdorf, Christian, 2013. Lorsque les entreprises formatrices sélectionnent en fonction du genre. Le recrutement des apprenti(e)s dans le secteur de la réparation automobile en Suisse. Revue française de pédagogie 183: 59–70.

Imdorf, Christian, 2017. Understanding discrimination in hiring apprentices: How training companies use ethnicity to avoid organisational trouble. Journal of Vocational Education and Training 69:405–423.

Imdorf, Christian, Lulu P. Shi, Stefan Sacchi, Robin Samuel, Christer Hyggen, Rumiana Stoilova, Gabriela Yordanova, Pepka Boyadjieva, Petya Illieva-Trichkova, Dimitris Parsanaglou and Aggeliki Yfanti. 2019. Scars of early job insecurity across Europe: Insights from a multi-country employer study. In Youth Unemployment and Job Insecurity in Europe: Problems, Risk Factors and Policies, eds. Björn Hvinden, Christer Hyggen, Mi Ah Schøyen and Tomáš Sirovátka, 93–116. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Kantaraki, Maroula, Maria Pagkaki and Evgenia Stamatelopoulou. 2008. Gender occupational segregation (vertical and horizontal): Discrimination and Inequality against women in education. Athens: Research Centre for Gender Equality.

Keuschnigg, Marc, and Tobias Wolbring. 2016. The Use of Field Experiments to Study Mechanisms of Discrimination. Analyse & Kritik 1:179–201.

Kricheli-Katz, Tamar. 2019. Us versus Them: The Responses of Managers to the Feminization of High-Status Occupations. Socius 5:1–15.

Kübler, Dorothea, Julia Schmid and Roland Stüber. 2018. Gender Discrimination in Hiring Across Occupations: A Nationally Representative Vignette Study. Labor Economics 55:215–229.

Leitner, Sigrid. 2003. Varieties of familism: The caring function of family in comparative perspective. European Societies 5:353–375.

Leuze, Kathrin, and Susanne Strauß. 2016. Why do occupations dominated by women pay less? How ‘female-typical’ work tasks and workingtime arrangements affect the gender wage gap among higher education graduates. Work, employment and society 30:802–820.

Levanon, Asaf, Paula England and Paul Allison. 2009. Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950–2000 U.S. Census Data. Social Forces 88:865–892.

Maas, Cora J. M., and Joop J. Hox. 2005. Sufficient Sample Sizes for Multilevel Modeling. Methodology 1:86–92.

Major, Debra, Donald D. Davies, Janis Sanchez, Heather J. Downey and Lisa M. Germano. 2007. Myths and realities in the IT workplace: Gender differences and similarities in climate perceptions. In Women and Minorities in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics. Upping the Numbers, eds. Ronald J. Burke and Mary C. Mathis, 71–90. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Mastekaasa, Arne, and Jens-Christian Smeby. 2008. Educational choice and persistence in male- and female-dominated fields. Higher Education 55:189–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9042-4.

Mooi-Reci, Irma, and Harry B. Ganzeboom. 2015. Unemployment scarring by gender: Human capital depreciation or stigmatization? Longitudinal evidence from the Netherlands, 1980–2000. Social Science Research 52:642–658.

National Statistical Institute, Republic of Bulgaria. 2019. Labour Force Survey. Persons employed 15+ (one-digit groups of individual occupations, occupational status, sex). http://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SJO01/- (Accessed: 9 July 2019).

NAV Statistics 2019. Arbeidsgiver- og arbeidstakerregisteret [Register of employers and employees in Norway]. Utdanning 2014: Likestilling i norsk arbeidsliv [Gender equality in Norway]. https://utdanning.no/likestilling (Accessed 23. June 2019).

NEGOTIATE (2020). NEGOTIATE Employer Survey. Scientific Use File. Data Documentation (2nd version). Oslo: OsloMet.

Neumark, David, Roy J. Bank and Kyle D. Van Nort, 1996. Sex Discrimination in Restaurant Hiring: An Audit Study. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111:915–941.

Ochsenfeld, Fabian. 2014. Why Do Women’s Fields of Study Pay Less? A Test of Devaluation, Human Capital, and Gender Role Theory. European Sociological Review 30:536–548.

Pedulla, David S. 2016. Penalized or Protected? Gender and the Consequences of Nonstandard and Mismatched Employment Histories. American Sociological Review 81:262–289.

Petersen, Trond, and Ishak Saporta. 2004. The Opportunity Structure for Discrimination. American Journal of Sociology 109:852–901.

Petit, Pascale. 2007. The Effects of Age and Family Constraints on Gender Hiring Discrimination: A Field Experiment in the French Financial Sector. Labour Economics 14:371–391.

Phelps, Edmund S. 1972. The Statistical Theory of Racism and Sexism. The American Economic Review 62:659–661.

Quillian, Lincoln, Anthony Heath, Devah Pager, Arnfinn H. Midtbøen, Fenella Fleischmann and Ole Hexel. 2019. Do Some Countries Discriminate More than Others? Evidence from 97 Field Experiments of Racial Discrimination in Hiring. Sociological Science 6:467–496.

Rabe-Hesketh, Sophia, and Anders Skrondal. 2012. Longitudinal and Multilevel Modelling using Stata, Volume I: Continuous Responses. College Station: Stata Press.

Ranson, Gillian, and William Joseph Reeves. 1996. Gender, Earnings and Proportions of Women. Lessons from a High-Tech Occupation. Gender & Society 10:168–184.

Reskin, Barbara F. 2003. Including Mechanisms in Our Models of Ascriptive Inequality. American Sociological Review 68:1–21.

Reskin, Barbara F., and Debra Branch McBrier. 2000. Why Not Ascription? Organizations’ Employment of Male and Female Managers. American Sociological Review 65:210–233.

Riach, Peter A., and Judith Rich. 2006. An Experimental Investigation of Sexual Discrimination in Hiring in the English Labor Market. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 6. doi:10.2202/1538-0637.1416.

Shi, Lulu P., Christian Imdorf, Robin Samuel and Stefan Sacchi. 2018. How Unemployment Scarring Affects Skilled Young Workers: Evidence from a Factorial Survey of Swiss Recruiters. Journal for Labour Market Research 52:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12651-018-0239-7.

Shih, Johanna. 2002. ‘... Yeah, I Could Hire This One, But I Know It’s Gonna Be a Problem’: How Race, Nativity and Gender Affect Employers’ Perceptions of the Manageability of Job Seekers. Ethnic and Racial Studies 25:99–119.

Stoilova, Rumiana. 2008. Impact of Gender on the Occupational Group of Programmers in Bulgaria. Sociological Problems Special Issue “Changes of work and the Knowledge–based society—the realities in South-Eastern Europe”: 94–117.

Teigen, Mari. 1999. Documenting Discrimination: A Study of Recruitment Cases Brought to the Norwegian Gender Equality Ombud. Gender, Work and Organization 6:91–105.

Weichselbaumer, Doris. 2004. Is it sex or personality? The impact of sex stereotypes on discrimination in applicant selection. Eastern Economic Journal 30:159–186.

Yavorsky, Jill E. 2019. Uneven Patterns of Inequality: An Audit Analysis of Hiring-Related Practices by Gendered and Classed Contexts. Social Forces, online first: doi: 10.1093/sf/soy123.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers, the guest editors, as well as Robin Samuel and Tamara Gutfleisch for helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding

This study was partly funded by the Horizon 2020 project “Negotiating early job-insecurity and labour market exclusion in Europe–NEGOTIATE” (Horizon 2020, Societal Challenge 6, H2020–YOUNG-SOCIETY-2014, YOUNG-1-2014).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

11577_2020_671_MOESM1_ESM.docx

The electronic supplementary materials contain figures and tables with further data description of the sample and of the design of the Factorial Survey Experiment as well as the models that serve as a basis for Figures 2 to 6.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertogg, A., Imdorf, C., Hyggen, C. et al. Gender Discrimination in the Hiring of Skilled Professionals in Two Male-Dominated Occupational Fields: A Factorial Survey Experiment with Real-World Vacancies and Recruiters in Four European Countries. Köln Z Soziol 72 (Suppl 1), 261–289 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00671-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-020-00671-6