Abstract

International business literature has historically been divided between scholars exploring the local obstacles foreign firms face (thereby overlooking foreign firms’ capacity to deploy advantages locally) and those examining the internationalisation of firm-specific advantages (thereby overlooking the peculiarities of the local context in which foreign firms deploy their advantages). We still do not completely understand the process by which multinational enterprises (MNEs) – especially service MNEs – develop competitive advantages in relation to the host environment. Using a multiple-case study of four multinational banking subsidiaries in India, this research aims to explore the variety of competitive advantages deployed by foreign multinational banks (MNBs) in a hostile, competitive environment: the Indian banking industry. This article’s main contribution is to bridge the gap between the obstacle-oriented internationalisation literature and the advantage-oriented literature through an exploration and comparison of a comprehensive set of locally relevant advantages deployed by the four MNBs studied. We introduce the concepts of global anchoring and local anchoring to make sense of the directionality of subsidiaries’ competitive advantages, and we explore their broad associations with subsidiaries’ commercial and financial performance. We conclude by discussing three theoretical lenses, situated at the intersection of the obstacle-oriented and advantage-oriented literatures, which can potentially account for the origins of competitive advantages in our sample, and we develop a series of propositions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In spite of the increasing centrality of service multinational enterprises (MNEs) in the world economy (Greenwood et al., 2010), international business theory has engaged with these actors to a lesser extent than with traditional manufacturing MNEs – in particular, their international expansion and the relevance of traditional competitive advantages to service MNEs (Bai et al., 2019; Chidlow et al., 2019). International business literature has historically been divided between scholars exploring the local obstacles foreign firms face (thereby overlooking foreign firms’ capacity to deploy advantages locally) (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Wu & Salomon, 2017; Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997) and those examining the internationalisation of firm-specific advantages (thereby overlooking the peculiarities of the local context in which foreign firms deploy their advantages) (Dunning, 1980; Nachum, 2003; Rugman & Verbeke, 1992). Scholars still do not completely understand the process by which foreign multinational banks (MNBs) develop competitive advantages in relation to the host environment (vis-à-vis domestic and other foreign firms), especially in a non-Western, emerging economy context characterised by both institutional voids (Khanna and Palepu, 2000) and hostile regulations. While a narrow economics-inspired literature stream tentatively addresses this topic (Berger et al., 2000; Jones, 1993; Williams, 1997; Yannopoulos, 1983), to the best of our knowledge no studies provide a comprehensive analysis and comparison of the variety of competitive advantages in a specific industry (here: Multinational banking) and host environment, and our article is aimed to fill this gap. Our research question, therefore, is as follows: What advantages do MNBs develop in a competitive and hostile environment?

To address this question, we conduct a multiple-case study of four MNB subsidiaries (British, French, Singaporean and South African) operating in India, using interviews with their chief executive officers (CEOs) and other stakeholders as well as archives and secondary data, to understand the nature of competitive advantages deployed by our sampled MNBs. The subsidiaries vary in terms of organisational characteristics (origin, age, local experience and/or knowledge and international presence), which allows us to pinpoint variations in the nature of competitive advantages developed in the host environment.

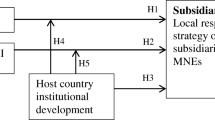

Building upon the work of Edman (2016), Sethi and Guisinger (2002), Sethi and Judge (2009), Shi and Hoskisson (2012) and Taussig (2017), our first contribution is to bridge the gap between the obstacle-oriented internationalisation literature (which focusses mainly on navigating local peculiarities) and the advantage-oriented literature (which focusses mainly on transferring homegrown advantages overseas), by including a comprehensive list of advantages relevant to multinational banking in relation to a specific host environment. Second, we link together the type of competitive advantages pursued and MNB subsidiaries’ performance. To do so, we introduce the concepts of global anchoring and local anchoring, which encompass both the marketing and organisational dimensions of international strategy. Including both dimensions allows us to pool together the various competitive advantages developed by each MNB subsidiary. We then develop a qualitative measure of MNB subsidiaries’ commercial and financial performance and evaluate the subsidiaries in relation to their global versus local anchoring strategies and competitive advantages pursued. Third, we develop a series of propositions to decipher the sources of competitive advantages, building on and assessing three theoretical lenses situated at the intersection of the obstacle-oriented and the advantages-oriented literatures: (1) institutional asymmetries (Fitzgerald, 2008; Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017), (2) comparative capitalism (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2018; Whitley, 1999) and (3) first-mover advantage (Lieberman & Montgomery, 1998). Furthermore, we add insights to the (emerging economy MNE-focused) leapfrogging literature (Hennart, 2012; Luo & Tung, 2007; Meyer, 2018) by arguing that, more than an economic/rational process, competitive advantages are the result of a path-dependent process embedded with socio-political dynamics and historical ties and cannot be easily fast-tracked or leapfrogged.

The remainder of the article is organised as follows. The next section presents a review of the various internationalisation theories and how they fit into the internationalisation of multinational banking activities, followed by a discussion of literature that focusses on the various (multinational banking–specific) ‘competitive advantages’ within the host environment. The following section contains a description of the context of the study and the methodology applied. We then present empirical results, structured around the four categories of competitive advantages identified in the literature, and an analysis of subsidiary performance. A discussion of these findings follows in which we introduce three theoretical lenses through which to examine the sources of competitive advantages in our sample and then present a series of propositions. We conclude with a discussion of our contributions, the limitations of this research and potential avenues for future research.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 Multinational Banks: A Central Yet Convoluted Actor in International Business

Most international business studies have historically focussed on ‘traditional’ manufacturing firms and their overseas expansion; thus, there have been debates as to whether traditional international business theory can explain the internationalisation of service MNEs with accuracy (Bai et al., 2019; Boddewyn et al., 1986; Williams, 2002). Service MNEs bear several distinctive characteristics that crease unique internationalisation challenges: intangibility (leading to high transaction costs when transferring across borders), inseparability (proximity to customers is required as production and consumption take place simultaneously) and heterogeneity (because each customer interaction is unique, a high degree of customisation is required) (Bai et al., 2019; Chidlow et al., 2019). However, even within the category of service MNEs, significant industry-level differences are present, which makes it difficult to consider service MNEs as a whole (Boddewyn et al., 1986). Venzin et al. (2008) differentiate hard service MNEs (production and consumption can be separated) and soft services MNEs (inseparability of production and consumption). They argue for instance that retail banking is mostly a soft service industry although there are elements of hard service too (i.e., some banking activities or products can be centralised in one location to a certain extent, depending on host-country regulations). Further to this, Bai et al. (2019) distinguish process-oriented service industries (more capital-intensive industries that require technical skills; e.g., the information technology industry), which can incorporate elements of standardisation, from content-oriented service industries (more labour-intensive industries that involve high consumer involvement; e.g., the hospitality industry), which are by nature much more localised. In this article, we focus on a specific type of process-oriented services: multinational banking activities.

As a specific type of professional service, multinational banking encompasses a set of heterogenous yet interrelated financial intermediation activities (Casson, 1990), and while some international banking activities can (to certain extent) be performed at home, a distinct characteristic of multinational banking is that the bank owns and controls banking activities in at least two countries (Casson, 1990). A bank is not an ordinary firm (Wilkins, 1990), and in this respect, MNBs represent a very specific type of MNE. Williams (2002) argues that foreign direct investment (FDI) in the banking industry cannot be explained with the same arguments used for other industries (Williams, 2002). A thriving accounting and organisational literature explores the management of professional service firms such as accounting, law and management consulting firms (Boussebaa, 2009; Morgan & Quack, 2005; Muzio & Faulconbridge, 2013), less so when it comes to multinational banking. A few scholars have made important contributions in the international business field (Aliber, 1984; Boddewyn et al., 1986; Casson, 1990; Sabi, 1988; Williams, 1997, 2002), but these studies are rather dated often embrace an economic perspective on the MNB. Interest has recently been renewed in the study of multinational banking using primarily a socio-political and/or (neo-)institutional lens (Caussat et al., 2019; Edman, 2015, 2016; Wu & Salomon, 2017), but overall, there remains important questions to be addressed regarding the internationalisation motivations and pattern of service MNEs, including MNBs (Bai et al., 2019).

This is surprising considering some of these corporations tend to display higher levels of internationalisation (Greenwood et al., 2010) and have long been central actors in the world economy. The pre-eminence of some of the largest MNBs goes back to the nineteenth century, when they acted as a primary economic conduit of colonial domination (Bonin & Valério 2018; Jones, 1993). Their continued expansion throughout the twentieth century has enabled them to become highly international (Boussebaa & Faulconbridge, 2019). Today, MNB subsidiaries in host countries might often be relatively small in size (as an example, foreign MNBs represent 7% of assets across the Indian banking sector), mainly (but not always) catering to the lucrative foreign and large domestic corporate lending segment, yet they perform critical roles in the host country: to connect it to the world economy, provide funding and technology where domestic banks fall short and facilitate technology transfer to domestic actors. They have not merely followed the international expansion of their clients but have also become proactive agents of globalization (Boussebaa & Faulconbridge, 2019), often with the support of their home governments.

However, beyond MNBs’ historical role as a financial arm of home governments overseas, we still know little about MNBs’ activities, their motivations to set up operations across borders (instead of fulfilling international banking activities at home and/or relying on correspondent banks overseas) and their competitive advantages in the international arena (vis-à-vis domestic and other foreign banks). In the same vein, Parada et al. note that “there appears to be no common pattern and little consistency to bank’s internationalisation strategies” (Parada et al., 2009, p. 209) in terms of entry mode, geographical pattern, or strategy. If one agrees that MNBs are not ordinary firms, how and to what extent can extant theories of internationalisation explain the international expansion of MNBs?

2.2 MNBs and Theories of Internationalisation

Berger et al. (2000) develop two hypotheses linked to multinational banking: the ‘home field advantage’ and the ‘global field advantage’. The home field advantage posits that MNBs are intrinsically at a disadvantage vis-à-vis domestic competitors, which results in hem being less efficient. The global field advantage hypothesis posits that MNBs can overcome these disadvantages by relying on a set of global competitive advantages. In this section, we review how the theories of internationalisation apply to multinational banking, following these two lines of argument – that is, the obstacle and advantages of being a foreign firm.

2.2.1 Theories Emphasising the Obstacles of Being a Foreign Firm

In line with the home field advantage hypothesis, a first theoretical perspective focusses on the obstacles to internationalisation that may result in additional costs of doing business abroad: ‘liability of foreignness’ (LOF) (Zaheer, 1995) increasing with institutional distance between the home and host markets (Eden & Miller, 2004); ‘liability of outsidership’ (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009); ‘liability of newness’ (Singh et al., 1986) or ‘liability of emergingness’ (Madhok & Keyhani, 2012) due to a lower reputation, lack of legitimacy and/or fewer capabilities and ownership advantages (Estrin et al., 2018; Ramamurti, 2012).. The Scandinavian approach proposes a sequential model of internationalisation whereby firms expand progressively, first to markets deemed relatively close and then further afield (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). The emphasis is on developing organisational learning (through local experience and/or networks) in a specific market, which is then transferred to other markets incorporating similar characteristics (Buckley et al., 2002).

This theoretical framework helps shed light on the internationalisation of service MNEs. They tend to display a higher degree of localisation (due to both the heterogeneity of service activities and the limited separability of production and consumption), which in turn tends to amplify the significance of the LOF in the service sector (Bai et al., 2019). Core to banking activities are business relations, and foreign firms may have difficulty fitting into local business networks due to the liability of outsidership (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009).

Nevertheless, the sequential framework may not accurately explain how MNBs internationalise, navigate local idiosyncrasies and remain locally competitive, for at least four somewhat conflicting reasons. First, because banking is highly regulated at the local level, the possibility for a foreign firm to partner with local firms to overcome the LOF/liability of outsidership is limited or at least significantly regulated. Therefore, a liability-based explanation cannot sufficiently explain why MNBs establish branches overseas; they must perceive some advantages over local competitors that would enable these MNBs to turn profitable. Second, while financial products offered can be standardised to a certain extent, nurturing business relations and more generally servicing customer expectations remain decisively local in scope (Prime & Usunier, 2015). Banking is a knowledge-driven industry (e.g., knowledge about customers, market information), and this knowledge is necessarily bound to a context. The scope for transferring organisational learning acquired in one country to another (i.e., sequential development) is thus relatively limited. Third, although local institutional actors (e.g., the host-country government, the central bank) represent a threat to MNBs’ internationalisation and local development, the relation between local institutional actors and MNBs is more convoluted: As an attribute of national sovereignty that also bears systemic risks for the global economy (Jeon et al., 2013), multinational banking operations depend on the political and economic relations between the home-country and the host-country governments, embedded together with multilateral agreements (e.g., World Trade Organization regulations stipulate that bilateral reciprocity must apply when it comes to the number of foreign banks allowed to set up operations in the host country). Therefore, liabilities-based research should also consider the firm’s home-country characteristics as a source of a potential advantage. Fourth and in summary, extant research has shown mixed evidence of a LOF effect in the banking industry. For example, comparing U.S. and British banks (two Western countries) operating in the City of London, Nachum (2003) finds no evidence of a LOF effect for U.S. banks and consequently no empirical support for a home-based advantage for British banks. Claessens et al. (2001) also find that foreign banks tend to perform better than domestic banks in developing economies. In contrast, Miller and Parkhe (2002) identify a LOF effect that emerges from the competitiveness of the home country relative to host country. Zaheer and Mosakowski (1997) also identify a LOF effect in the interbank currency trading rooms, which increases in the first nine years of local presence and declines with a long-term commitment to the host environment. Wu and Salomon (2017) show that U.S. regulators tend to initiate more enforcement actions against foreign banks than they do against domestic banks but that the magnitude of the discrimination varies according to the quality of human capital and experience in the host country. In summary, it is not clear the extent to which sequential theory and the LOF framework may apply to multinational banking activities. Further research comparing various multinational banks in a non-Anglo-American environment is necessary to unpack the international dynamics at play in this industry.

2.2.2 Theories Emphasising the Advantages of Foreign Firms

We also know that foreign firms may hold and/or develop competitive advantages abroad vis-à-vis domestic firms and other foreign firms. For instance, Taussig (2017) shows that firms operating in globally oriented industries are less likely to suffer from local idiosyncrasies, particularly process-oriented services such as banking activities, in which a certain degree of standardisation may coexist with some required local adaptations. In this section, we explore the various theories around the global field advantage hypothesis (Berger et al., 2000).

First, globalisation theories tend to consider the world as homogeneous and imply that firms can apply a standardised recipe for success (Levitt, 1983; Porter, 1980), developed at home and targeting the rest of the world, to enjoy the advantages of scale economies and compete internationally. This view has been largely criticised for being restricted to small pockets of the world economy (e.g., industrialised economies, specific industries), failing to appreciate the institutional differences across national systems (Fitzgerald, 2008; Ghemawat, 2001) and overlooking the difficulties of transferring firm-specific advantages (Rugman & Verbeke, 2008). Moreover, this set of theories does not sit particularly well in the context of multinational banking studies, due to the presence of strong local regulations and localised demand.

A second strand of international business literature addresses the internal dimension underlying MNEs’ competitive advantages in a world characterised by market imperfections (e.g., tariffs). Internalisation theory (Buckley & Casson, 2009; Rugman, 1981) argues that keeping (internalising) activities within MNEs can be more effective when expanding overseas than through market mechanisms (e.g., exporting, licensing) because it helps reduce transaction costs of international operations and locks in sensitive technology and information. One of the main benefits of this theoretical perspective is that it explains how firms can protect specific advantages developed at home and use them overseas (non-location-bound advantages; Rugman & Verbeke, 1992). In the context of multinational banking, we know that quality of information is central to MNBs’ performance (Boddewyn et al., 1986). However, because information is difficult to obtain via market transaction (William 1997), human and relational capital are important factors shaping competitive advantages in the banking industry (Casson, 1990). In this respect, if MNBs exist (as opposed to correspondent banking), it is because information is better sheltered from competition in the closed information-gathering centre that the MNB provides. Linked to this theory, Dunning’s (1988) eclectic paradigm combines ownership, location and internalisation advantages to explain FDI commitment and the existence of MNEs, in spite of significant costs of doing business abroad. Ownership advantages developed at home are essential in this framework, as they allow MNEs to compete with domestic incumbents (Williams, 1997). One such ownership advantage in multinational banking is access to key currencies for international trade and finance. According to this ‘currency clientele’ argument, customers seek to transact with an MNB from the country of origin of the transaction currency (Aliber, 1984). In other words, certain MNBs holding specific firm-level, country-level advantages can outperform domestic incumbents (Berger et al., 2000; Williams, 1997).

Nevertheless, this theoretical lens can only partially explain internationalisation patterns in multinational banking, for several reasons. First, if access to key international currencies represents one of the main ownership advantages, such an operation can be performed at home and through local correspondents, thus, this argument does not explain the existence of MNB branches in the host environment. Second, and more importantly, this set of theories focusses on exploiting homegrown knowledge internationally (Buckley et al., 2002; Dunning, 1988); however, banking knowledge remains significantly bound to location, which results in a limited potential for knowledge transfer from an MNB’s headquarters. More generally, researchers have criticised the eclectic paradigm for its tendency to downplay the host environment dynamics (e.g., the role of the host government). This set of theories has been developed in the context of sophisticated economies, and thus, it remains unknown how the market transaction versus internalisation decision is evaluated in an emerging market characterised by institutional voids in the political system as well as in the product, labour and financial markets (Khanna & Palepu, 2000). In this context, how can we explain the substantial number of MNBs that internalise rather than establish joint ventures or licence their activities? Due to the sovereignty attribute of the industry, institutional hurdles such as local regulations may generate significant transaction costs when doing business abroad (e.g., costs of negotiating, dealing and complying with local institutions; Wu & Salomon, 2017), which internalisation theory does not account for with accuracy. In a nutshell, internalisation theory and the eclectic paradigm are mainly theories of homegrown firm-specific advantages transferred overseas. They are less satisfactory when it comes to linking these firm-specific advantages with the peculiarities of the host environment (as opposed to absolute advantages that hold across any location).

2.2.3 Foreign Investment Banks’ Competitive Advantages in Relation to the Host Environment

In spite of these limitations, MNBs must see certain local advantages if we are to explain the number of them that operate across institutionally complex settings such as the Indian banking environment examined herein. Building on extant literature situated at the intersection of the obstacle-oriented literature (which focusses mainly on navigating local peculiarities) and the advantage-oriented literature (which focusses mainly on how to transfer homegrown advantages), we identify a limited number of ‘competitive advantages’ deployed within or in relation to the host environment, which, although distinct, have often been used interchangeably (see Table 1 for a summary).

First, greater host-country experience, and the accumulation of knowledge that goes along with it, can help reduce the LOF (Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997) vis-à-vis domestic firms. Moreover, it can also be a source of competitive advantage vis-à-vis younger and less experienced foreign firms that may suffer a form of liability of newness (Singh et al., 1986). In the context of the U.S. banking industry, Wu and Salomon (2017) find that foreign banks with higher-quality human capital and more host-country experience are less likely to face regulatory liabilities. In contrast, Rickley and Karim (2018) suggest that as institutional distance increases, firms may prefer to rely on expatriates who are able to transfer organisational knowledge over local managers with significant host-country knowledge, when aiming to benefit from prior international experience. Thus, extant literature suggests that more host-country experience and/or localising subsidiaries’ top management can help reduce the LOF vis-à-vis domestic firms and can create the conditions of a competitive advantage vis-à-vis other foreign firms. However, ambiguity remains regarding which of the two strategies is most effective in gaining a local competitive advantage for large MNEs. An alternative strategy consists of partnering with local firms (e.g., joint venture, strategic alliance, licensing) to accrue local knowledge. However, many firms dismiss this strategy because joint ventures are often short-lived [due to, e.g., strategy, cultural or intellectual property conflicts (Meschi & Riccio, 2008); trust and legitimacy issues (Lu & Xu, 2006)] and are subject to high regulatory scrutiny, particularly in the banking industry.

Second, central to the theory explaining FDI patterns is the idea that firms must be equipped with specific advantages to be able to commit to FDI and compete overseas against both foreign and domestic firms (Dunning, 1980). Rooted in the resource-based theory, firm-specific advantages (FSAs) can originate in either in the home environment (non-location-bound advantages) or the host environment (location-bound environment) (Rugman & Verbeke, 1992). In other words, FSAs include ownership advantages (developed irrespective of the host-country environment; Dunning, 1980) as well as advantages linked to the foreignness of the firm in the host-country environment (Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017). While the international business literature has extensively documented the former type of advantage, investigating the advantages linked to the foreignness of the firm offers new avenues for understanding firms’ internationalisation. To clarify, ownership advantages (e.g., superior technology) are homegrown and can be applied across the board; they have little to do with being a foreigner in a specific host environment. Assets of foreignness (AOFs) are exclusively linked to the foreignness attribute in a specific host country (Sethi & Judge, 2009); they might not necessarily involve tangible assets as such (Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017). Extant literature is still nascent about the ramifications of the AOF phenomenon, which, similar to the LOF phenomenon, can be nuanced (Sethi & Guisinger, 2002). Nevertheless, at least seven specific mechanisms constitutive of an AOF effect can be identified in the context of multinational banking activities:

-

1.

Foreign firms can derive their AOF from superior or unique technological capabilities, which can feed into a competitive advantage depending on the level of technological sophistication in the host environment. To consider this advantage an AOF (as opposed to a classic ownership advantage), it must be linked to the MNB’s foreignness in the host environment. For instance, an MNB may well possess a homegrown product that fills a specific technological gap in the host environment (Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017).

-

2.

Home-country banking regulations (e.g., regulatory supervision, capital requirements) may impact a given MNB’s cost structure and competitiveness more severely than those of other domestic and foreign MNBs (Cho, 1986).

-

3.

As interest rates (partially) reflect the economic situation of a country, differences between home and host economies generate effective interest rate differences, which may increase the relative price competitiveness of foreign MNBs from a specific country or currency area (Cho, 1986).

-

4.

Firms can also derive AOF from a positive country-of-origin (COO) effect (Moeller et al., 2013), which refers to how the local public authorities and customers perceive the given firm’s nationality. Furthermore, Yannopoulos (1983) and Williams (1997) argue that MNBs’ competitiveness can be derived from long-term perceived differentiations based on a series of factors such as the bank’s size, credit rating, nationality (cf., COO effect) and the perceived probability of loan renewal. However, one issue with the COO explanation is that it is not easy to assess such an effect due to its intrinsic subjectivity. Literature has also shown that emerging economy firms are more likely to face a negative COO association (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Ramachandran & Pant, 2010), though this effect needs further assessment in the context of an emerging (as opposed to advanced) economy.

-

5.

Being foreign can also allow firms to exempt themselves from certain local norms (Shi & Hoskisson, 2012), as Edman (2015) shows in the case of Citibank in Japan, which then enables them to avoid localising certain aspects of the business (thereby reducing operational costs) and/or to import (technological/managerial) innovation.

-

6.

Another AOF strategy involves developing specific ownership advantages that are rooted in the host environment, such as host-country tailor-made products that are superior to local competitors’ (Delios & Beamish, 2001; Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017).

-

7.

Certain foreign firms may receive preferential treatment from local authorities in the form of favourable regulations, tax breaks or subsidies (Sethi & Guisinger, 2002; Sethi & Judge, 2009). Foreign firms may also receive dedicated support from their home-country government, which can help boost their competitiveness, particularly state interventionist economies such as China (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2010) or even France (Schmidt, 2016 classifies France as a ‘state-enhanced market economy’ whereby the government provides extensive resources and political support to a limited number of internationalising national champions). While political relationships may be less relevant in sophisticated economies based on market mechanisms, they can generate a substantial competitive advantage in emerging markets characterised by significant institutional voids (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genç, 2008; Doh et al., 2017).

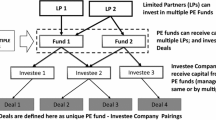

Third, large MNEs can also leverage their multinationality in the host-environment to compete with domestic firms. Assets of multinationality (AOMs) arise from firms’ global networks. They provide clear benefits (Cho, 1986; Sethi & Judge, 2009): knowledge and technology transfer, cost structure reduction through outsourcing and offshoring strategies, increased international exposure of the workforce, access to capital markets and availability of capital at a lower cost, exploitation of currency-market volatility and tax optimisation and improved networks for information gathering and addressing local clients’ global needs; in addition, albeit less important for multinational banking, they can provide economies of scale. Losses in one specific location, arising from the additional costs of the LOF, for instance, can be offset or subsidised by profits accumulated in other locations. Sabi (1988) also shows that MNB subsidiaries’ performance is associated with the size of the MNB’s home market as it is correlated with larger trade and investment volumes between the host and home countries. We can also integrate Aliber’s (1984) ‘currency clientele’ argument here, whereby large MNBs have better access to international currencies (e.g., access to dollar currency through U.S. subsidiary) than domestic banks but also other foreign banks with a more limited international footprint. Hence, AOMs are assets that domestic firms and smaller foreign firms cannot access and, unlike AOFs, are born and developed outside the host country (Mallon & Fainshmidt, 2017). Empirical evidence of the existence of an AOM effect in the banking industry is still thin, though Claessens et al. (2001) show that advanced-economy MNBs operating in emerging economies tend to be more profitable and efficient than their domestic counterparts. The authors attribute the superior performance of advanced-economy MNBs to their ability to access parent firms’ capital and organisational knowledge. Venzin et al. (2008) also observe that the significance of the multinational-performance relation depends on the nature of the bank (knowledge-intensive vs. capital-intensive), home-country characteristics (small vs. big; advanced vs. emerging) as well as the bank’s internationalisation strategy (exploitation vs. exploration).

Fourth, network externalities achieved through a process of agglomeration into specific geographic locations bring several important benefits to foreign firms: (1) they promote cooperation and local information and knowledge sharing (Porta et al., 2002), thereby reducing the potential LOFs/liabilities of outsidership associated with the sequential theory of internationalisation; (2) they optimise transport costs in relation to suppliers/distributors and economies of scale, particularly in manufacturing industries (Krugman, 1991); and (3) they help develop local legitimacy by following (legitimate) competitors’ (location) strategies. In the banking industry context, Barreto and Baden-Fuller (2006) and Deephouse (1996) highlight mimicking effects in the retail banking segment. There is also a strong agglomeration effect in the network-oriented banking industry, incentivised by the need to locate near large firms, regulatory authorities, law firms and the like. Nevertheless, it is not clear whether all firms benefit from agglomeration externalities. Three counterarguments can be advanced here: (1) network externalities can be negative if they lead to sharing too much strategic knowledge or even technological leakages (Mariotti et al., 2019) (though we acknowledge technological leakages are perhaps slightly less relevant to multinational banking as there is little technology involved), (2) network externalities are stronger if the underlying motivation is to achieve real economic gains rather than legitimacy, and (3) the effect is also stronger among firms of the same nationality (Chang & Park, 2005; Chung & Song, 2004). Hence, while agglomeration can lead to a competitive advantage against other foreign firms, it seems that not all foreign firms can enjoy its benefits to the same extent, and a more firm-specific approach is required.

2.3 Aims of the Research

We still understand little about the process through which foreign MNBs become competitive in a host environment (vis-à-vis domestic and other foreign MNBs), even less so in a non-Western, emerging economy context characterised by institutional voids (Khanna & Palepu, 2000). How can we explain the presence of MNBs in a hostile, regulated environment (e.g., instead of the MNB using a correspondent)? What kind of competitive advantages do MNBs develop in and for the host environment? Extant literature does highlight a set of competitive advantages that are developed in relation to the host environment (as opposed to across the board): host-country experience and knowledge, which can serve as specific ownership advantages developed at home and abroad that lead to AOFs, AOMs and network externalities. However, these advantages need further firm-level rather than industry-level empirical unpacking. In short, we know too little about why and how foreign firms that display certain organisational characteristics benefit from some advantages that other firms with a different set of organisational characteristics do not benefit from.

Our research combines three aims: (1) to further our understanding of the internationalisation process in the banking industry, building on sequential and internalisation theories; (2) to identify the advantages on which different foreign MNBs may rely through a comparison of foreign MNBs with different organisational characteristics (origin, age, local experience and/or knowledge and international presence) and (3) to study the development of these competitive advantages in a non-Western, non-Anglo-American environment. In doing so, we aim to explore the broader socio-political context within which competitive advantages are developed. This leads us to formulate the following research question: What advantages do multinational banks develop in a competitive and hostile environment?

3 Research Design

To investigate the dynamics in the multinational banking industry, we develop a multiple-case study of four MNB subsidiaries embedded within the same context (India), which allows us to draw comparisons between foreign MNBs, each with a different set of organisational characteristics. We first introduce the context of our research, and then we explain our research methodology, data collection and analysis process.

3.1 Research Context: Foreign MNBs in India

Studies that investigate foreign banking activities have tended to focus on the Anglo-American context or actors (Nachum, 2003; Wu & Salomon, 2017), sometimes in a Japanese context (e.g., Edman, 2015), but most of the time across a large number of countries (Miller & Parkhe, 2002; Taussig, 2017; Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997). Fewer studies have examined specific emerging economies, which are particularly interesting when it comes to banking activities because they are characterised by institutional voids in the product, capital and labour markets (Khanna & Palepu, 2000) and the enormous influence of socio-political institutions (in the form of, e.g., government, local communities, nongovernmental organizations; Sheth, 2011). We locate our study in India, which provides an interesting site for researching foreign MNBs for several reasons. Although the country is experiencing a long-term transition to a market-based economy, it is still characterised by the presence of incomplete markets (in terms of market infrastructure and intermediaries, information circulation, skills, etc.) often filled by business group structures (Manikandan & Ramachandran, 2015). In addition, studies show that public authorities are keen on protecting national sovereignty and domestic firms via foreign entry regulations, as a result of which India is acknowledged to be a difficult environment to navigate from a foreign firm’s perspective (Budhwar et al., 2010).

International business literature investigating the Indian context tends to focus on the organisation and internationalisation of Indian business groups (Kedia et al., 2006), the management of cultural interactions within an MNE subsidiary (Becker-Ritterspach & Raaijman, 2013) and, more generally, the cultural distinctions of the Indian business environment and Indian managers (‘the Indian way’; e.g., Cappelli et al., 2010). As such, relatively little international business literature addresses not only the obstacles but also the advantages of MNCs in the Indian environment (Caussat et al., 2019; Elg et al., 2015; Pant & Ramachandran, 2017).

Typical of liberalising emerging economies, the Indian banking sector is dominated by a few large public-sector banks (65.8% of credits in 2017), although some aggressive new private-sector banks have emerged in the wake of economic liberalisation (combined with old private-sector banks: 26.9% of credits in 2017). Foreign banks make up only 4.2% of credits as of 2017. In 2019, India had 46 foreign banks, whose main aim is to connect the Indian economy to the rest of the world. As such, foreign banks are profitable in India, although the market in which they compete remains very small (mainly cross-border and large-capitalisation investment banking) due to India’s tight regulatory framework and is thus extremely competitive (it is worth noting that foreign MNBs account for a slightly larger share of credits within these particular segments, though no data could be retrieved). Foreign MNBs operating in India need to integrate local networks to both overcome unfavourable regulatory treatments and access insider information, and they must also differentiate themselves from domestic and foreign competition. For these reasons, the banking sector represents an ideal service industry in which to study the development of competitive advantages of various foreign MNEs operating in India.

3.2 Research Methodology

This article investigates the nature of competitive advantages in the multinational banking industry through a multiple-case study research design. The case study methodology is particularly relevant when the context (here: The Indian banking environment) and the phenomenon under study (here: The competitive advantages developed by MNB subsidiaries in India) are embedded (Yin, 2014). As this article aims to refine our understanding of how firms develop competitive advantages, we deemed a qualitative research design appropriate. Our research design draws from the natural experiment case study tradition (Welch et al., 2011), the aim of which is to test the variables emerging from the literature review (here: A set of competitive advantages) and discuss rival explanations. Nevertheless, explanations developed here are contextual: We seek to gain some understanding of how MNBs (a comparatively understudied international business actors) develop their advantages, not across many countries, but in relation to the host environment (or context) of our study.

Our research design is built around four cases (unit of sampling: MNB subsidiary operating in India), following a process of convenience sampling aimed at maximizing organisational characteristics variations. We consider these cases typical of foreign MNBs operating in India (in terms of activities, origin, experience and size), which thereby enhances the likelihood of sample representativeness; in other words, this variety provides external validity. Our four cases vary in terms of origin (or nationality: British, French, Singaporean and South African), relation to India, group size, age (commensurate with international experience), local experience, size of local operations and diversification of activities. These variations allow us to maximise the scope of competitive advantages developed in the host environment. Table 2 displays the basic characteristics of our four cases.

Our unit of analysis is the competitive advantages of the subsidiary in the host environment, and the main unit of respondent is the MNB subsidiary’s country manager (also called subsidiary CEOs). We collected primary data using 10 semistructured interviews with MNB subsidiaries’ country managers (4 with the French MNB, 2 with the Singaporean MNB and 4 with the South African MNB), as well as 1 interview each with a top manager of the British and French MNBs. We acknowledge a potential limitation in not having an interview with British MNB subsidiary’s country manager; nevertheless, we were still able to gather data about the British MNB subsidiary through an interview with an Indian top manager who started his career in the Indian subsidiary and who is now working at the British MNB’s headquarters. We conducted interviews in English and French, and they lasted one to one and a half hours. They consisted of questions related to (1) the importance of the Indian market and the Indian subsidiary for the MNB as a whole, (2) the obstacles in the host environment and subsidiaries’ interactions with local socio-political actors and (3) the subsidiary’s competitive advantages vis-à-vis its competitors. Because interviewees expressed some confidentiality concerns, we did not record interviews; however, to increase internal validity, we sent interview transcripts to interviewees for amendments and validation.

Internal validity was also strengthened through a series of 7 interviews with other MNB subsidiaries country managers and headquarters-level top managers: 3 interviews with two other French MNBs (2 interviews with Indian CEOs and 1 with a headquarters manager), 2 interviews with a German MNB mergers and acquisitions associate based out of India (who previously worked for the British MNB), 1 interview with the Canadian MNB Indian CEO and 1 interview with the Emirati MNB India CEO (who previously worked for the French MNB). These interviews allowed us not only to triangulate information related to the competitive advantages of our four MNBs but also to collect more data on foreign MNB subsidiaries in general and about their relationship with institutional actors in particular. We also conducted interviews with nonbanking MNE subsidiaries’ country managers (3 interviews) to understand their perception of foreign MNBs in India, as well as a trade representative at the Embassy of France in India (1 interview) to explore the potential links between the French MNB and other institutional actors. We attempted to replicate this process for Singapore and South Africa, but their institutional representation in India is significantly smaller; that is, they do not have similar intermediaries located in India. A side interview with a UK trade representative confirmed that British institutional representations in India focus on export promotion and thus have limited interactions with the British MNB subsidiary. Last, we conducted an interview with a banking and economic editor of a leading Indian daily (1 interview) to critically discuss the competitive advantages of foreign MNBs versus domestic banks. In summary, the primary data set comprises 24 interviews (12 with sampled MNB subsidiaries, 7 with other MNB subsidiaries and headquarters-level top managers and 5 with other stakeholders).

We also gathered the following secondary data to document our four case studies as well as further increase the internal validity of the research design:

-

1.

Documentation:

-

•

Documents published by MNBs: financials, public relation statements and documents about the history of the subsidiary and/or the bank;

-

•

Data published by India’s central bank (RBI): number of branches and ratio of nonperforming assets;

-

•

Local press articles (The Economic Times, The Hindu Business Line, Mint).

-

2.

Archival data collected online (the British MNB) and in the archive centre of the French MNB (one four-hour session): information about the activity of their Indian subsidiary (from correspondence, pictures and internal reports).

The data analysis process followed a thematic analytical strategy guided by existing theory (Eisenhardt, 1989). The literature review has highlighted a set of competitive advantages that MNBs may have in relation to the host environment (as opposed to across the board): host-country experience and knowledge, as well as specific ownership advantages developed at home and abroad, including AOFs, AOMs and network externalities. We follow this structure to analyse data across each case and identify similarities and differences between each MNB subsidiary.

4 Empirical Findings

As a result of hostile local regulations, foreign MNBs in India have a small presence in India, accounting for approximately 4.2% of credits (as of 2017); yet they fulfil an important role in areas in which domestic banks are not able to expand to or are less competitive. We report here findings on the competitive advantages tentatively developed by each MNB vis-à-vis domestic banks as well as, more importantly, other foreign MNB subsidiaries in India. As we explore in the literature review, studies show (at least) four broad categories of competitive advantages: (1) host-country experience and knowledge; (2) specific ownership advantages developed at home and in India leading to AOF; (3) AOM and (4) advantages due to externalities. We then explore the performance each MNB subsidiary. Due to space restrictions, we present only a selection of key templates.

4.1 Host-Country Experience and Knowledge

Foreign subsidiaries can accrue host-country experience and knowledge in at least three ways: (1) a historical presence leading to the development over time of trustful business relationships, (2) hiring or posting local top managers for the local subsidiary and at the headquarters and (3) partnering with local companies to access local knowledge and networks.

Both the British and French MNBs have been operating in India for a longer period of time (the British MNB since 1853 and the French MNB since 1860) than the Singaporean and South African MNBs (1995 and 2009, respectively). Although both British and French MNBs were incorporated during the colonial period, we observed a noticeable difference. The British MNB was originally conceived as a colonial bank: it was established in 1853 through a royal charter as a bank for the Asian and Pacific colonies and progressively became one of largest banks operating in the ‘British Raj’. The bank did suffer a setback after India’s independence in 1947 and the gradual tightening of regulations against foreign companies (at least two landmark legislations contributed to deteriorating the business climate of foreign investors in India: the 1969 Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practice Act and the 1973 Foreign Exchange Regulation Act; Faust, 2020), yet it remains today the largest foreign MNBs operating in India. In contrast, the French MNB was not established as a colonial bank per se and never really possessed significant operations within the French colonial empire (Bonin, 1991). As a trade intermediary across the empires, the French MNB was known outside the French colonial empire simply as ‘French Bank’. In present-day India, however the bank has developed a portfolio of activities (including small retail operations) and is a sizable (though not one of the largest) foreign MNB.

As latecomers, the Singaporean and South African MNB subsidiaries have faced a number of obstacles. First, the following quote illustrates the difficulty of finding a market positioning in an already saturated market, reflecting a latecomer disadvantage (vs. first-mover advantage):

South African MNB CEO (Interview 1): ‘In April 2012, we started retail and commercial activities. What is bankable is overcrowded. All the banks are present in India: from very efficient ones to those with large balance sheets. We have to find our unique positioning [, which may be] perhaps slightly riskier’.

The second obstacle faced by Singaporean and South African MNBs pertains to the liability of newness in the Indian market. More extensive host-country experience is generally associated with deeper, more trusting business relationships and an overall higher commercial performance. Indeed, with regard to interacting with the local business community, British and French MNB subsidiaries did not report facing any particular issues, noting that they knew their market and were well acquainted with their customers. They were also able to recruit high-profile and well-networked senior bankers to develop relationships with potential corporate clients, which resulted in a low rate of nonperforming assets (NPAs; e.g., nonrepaid loans – a high NPA ratio implies that a larger proportion of clients do not repay their loans): The British MNB’s net NPA ratio stood at 0.45% in March 2014, 1.07% in March 2016 and 0.58% in March 2019; while the French MNB’s net NPA ratio consistently remained at 0% between March 2015 and March 2018.

Having entered India more recently, the South African MNB and, to a slightly lesser extent, the Singaporean MNB have been struggling with a high rate of loan nonrepayment: The Singaporean MNB’s net NPA ratio stood at 10.21% in March 2014, 4.34% in March 2015 and 3.13% in March 2019. The South African MNB’s gross NPA ratio stood at 15% in March 2014, and its net NPA ratio stood at 12.85% in March 2017 and 5.18% in March 2019 before a major write-off. The South African bank CEO confirmed these figures, noting that the bank had to rethink its India strategy amid rising NPAs: ‘We cannot target large corporates, as we cannot offer them good prices. We therefore target the mid-market: This is the way to go, though the risk profile is different. We’ve got to select the customers wisely (why this company? why this sector? what relation do we have with senior managers and promoters?) and select the good origination corresponding to the appropriate level of risk. As a result, we have exited some businesses deemed too risky (i.e., certain industries with a higher risk profile and depending on the quality of the relation with senior managers and promoters). Beginning [in] 2012, we got three NPAs, which was quite normal as we were building the structure. Now, we found the right origination’. (Interview 1 with South African MNB CEO).

Partly to offset their late entry and a potential liability of newness, both the Singaporean and South African MNB subsidiaries have been keen to localise their staff. The British MNB has also gradually localised its Indian subsidiary’s staff composition in the wake of India’s independence and is now fully managed by Indian nationals. The French MNB follows a different pattern in which expatriates are sent from the headquarters to fill top management positions within the Indian subsidiary. The Singaporean MNB CEO highlights this contrast in the following quote, also noting that knowledge and awareness about India must be developed at not only the subsidiary but also headquarters level (there are two Indian nationals sitting at the board of Singaporean MNB: the group CEO and an independent director): ‘Lots of people are sent from India to Singapore, and the CEO in Singapore is Indian! We do not have a colonial approach, like sending a French to represent the French bank in India! When it comes to the business, Indian bankers have more knowledge about India’. (Interview 2 with Singaporean MNB CEO).

Although the South African bank’s top management is predominantly composed of white, Afrikaner profiles (no Indian nationals), the Indian subsidiary is under full local management and short-term transfer opportunities from Mumbai to Johannesburg have been institutionally organised. Both the British and Singaporean MNBs have also institutionalised extensive internal mobilities between the headquarters and the subsidiaries (the Singaporean MNB’s CEO is an Indian national). By contrast, transfers from India to the headquarters are limited for the French MNB, taking place mainly at the regional level (from India to the regional headquarters in Singapore, Hong Kong or Dubai). That said, the French MNB seems to be gradually moving toward a more international (as opposed to French) corporate culture: ‘At (French bank 2) in Asia, there are many Indians who logically understand India better than expats. This brings tensions down. And also, the exchanges with Britain have reduced the cultural gap significantly, unlike in Japan or Korea. In my local management committee, people are very Anglo-Saxonised’. (Interview 4 with French MNB CEO).

Last, while the top management of Indian operations remains for the most part under the hands of expats, the French MNB reported being keen to develop partnerships with local brokers, retailers and asset management companies to provide technological know-how and reputational gains in exchange for local network and knowledge acquisitions. In contrast, the British, Singaporean and South African MNBs reported not yet having entered into any banking and financial partnerships with local companies (though the Singaporean MNB did establish one partnership with local insurance companies to develop a new technological platform).

4.2 Specific Ownership Advantages Developed at Home and in India

To distinguish themselves from both foreign and domestic competition, our four multinational banks noted that they relied on specific ownership advantages developed both at home (which nevertheless impacted the host environment) and in the host environment, such as the following: (1) possessing a unique global or local asset or expertise in relation to the host environment; (2) enjoying the benefits of a positive reputation, also often associated with a positive local perception of the organisation’s country of origin; (3) the possibility of being exempted from certain local norms due to their foreignness; (4) developing specific advantages in and for the host environment and (5) receiving preferential treatment from home-country authorities and/or local authorities in the form of favourable regulations, tax breaks or subsidiaries.

First, all four MNBs tend to focus on cross-border operations to support large corporations in their internationalisation endeavour (into/from India), though the British MNB also has significant local retail operations through a network of 100 branches across 43 cities in India (the Singaporean MNB subsidiary has 27 retail branches; the French MNB subsidiary has a very small online retail activity). When it comes to possessing specific ownership advantages, the French MNB has positioned itself as a world leader in a very specific niche market: project finance. For instance, it is the world leader in real estate and energy finance. The firm’s technical expertise is well recognised among Indian business groups as they fulfil a vital role for their internationalisation: ‘French banks have developed a distinct expertise in project finance because they originate from a developed economy, so they’ve been doing these activities for a very long time. There is a considerable knowledge and technical gap with Indian banks. Indian customers with international operations don’t go to Indian banks for this kind of expertise’. (Interview 3 with French MNB CEO). The British MNB has developed two types of advantages: (1) a strong expertise in commodities trading, which is one of the historical positions of British banking going back to the nineteenth century (Jones 1990); and (2) deep knowledge of emerging markets (Interview with British MNB top manager: (HQ) ‘The bank is THE “emerging market” bank. We don’t really operate in the UK, our DNA is the emerging markets, especially Asia, Africa and Middle East’). The bank derived 68% of its 2018 net income from Asian markets alone.

In contrast, the Singaporean and South African MNBs have focussed on adapting their operations to embed themselves within the Indian environment, with the aim of winning favour with the regulator to compete with foreign and domestic banks. Although these banks do possess valuable expertise (digital banking for the Singaporean MNB and bottom-of-pyramid banking for the South African MNB), they did not use it to strengthen their market position in India, mainly focussing on cross-border operations. Consider the contrast between the following quotes:

French MNB CEO (Interview 2): ‘Our strategy is to continue to serve India with international operations’.

South African MNB CEO (Interview 1): ‘We need very Indianised technology solutions. I often take the example of McDonalds: They had to adapt to the Indian marker and open pure veg outlets. In order for us to adapt, we need to understand what the local need is’.

However, the Singaporean MNB also aims to differentiate itself from its competition through its ‘Made in India’ digital innovation. The bank has set up a technology development centre in India (the first of its kind outside Singapore), in a move that signals increasing local ambitions via locally grown innovation that could potentially feed into a future AOF in the form of ownership advantage specifically targeting the host environment.

Second, both the British and French MNBs originating from the so-called cluster of Western countries may enjoy the benefits of a positive country-of-origin (COO) effect when dealing with local customers, an advantage firms from emerging and newly industrialised economies may not be able to expect (Estrin et al., 2018; Madhok & Keyhani, 2012). For example, the British MNB enjoys a strong corporate reputation in India by not only cultivating the image of a British bank (‘British-ness’ and banking are associated with a positive COO; Aichner, 2014) but also representing itself as being both an emerging market bank and a local one, as reflected in their value statement: ‘We’ve been in India for over 160 years. We use our global capabilities and deep local knowledge in India to provide a wide-range of products and services to meet the needs of our personal banking and business customers’. The French MNB subsidiary, in addition to developing global expertise and strategy, has rather been cultivating a global (as opposed to local) image: subsidiary CEOs are (and have remained) almost exclusively French nationals sent from the headquarters. The bank has also been keen on highlighting global expertise (e.g., the website displays a long list of global accolades such as ‘Best Bank for Sustainable Finance’; although both the British and Singaporean MNBs also display some awards, theirs are more regional or Asian in scope). Last, The French MNB subsidiary aimed to be perceived as an international bank; the CEO was reluctant to develop local communication campaigns, opting to emphasise the international character of the bank instead.

In contrast, both the South African and Singaporean MNBs have less brand recognition. To offset this lack of reputation, the Singaporean and – to a slightly lesser extent – South African MNB subsidiaries have tended to cultivate a local identity through communications emphasising their local attachment. The Singaporean MNB relies on local celebrities for some of its events (e.g., for the launch of their digital bank, the bank hired a famous cricket star as the face of the campaign) and also sponsors a local cricket team: ‘We are running extensive local communication both digitally and physically.… We have recently been running a specific campaign with large posters across cities’ (Interview 1 with Singaporean MNB CEO).

Third, the French MNB has been able to exempt itself from local norms, especially when it comes to workplace culture. As French MNB 1 CEO puts it: ‘We live according to our international culture.… We don’t work like an Indian bank’. The British, Singaporean and South African MNBs, in addition to adapting their local offerings, have also been keener to show flexibility and make some workplace adjustments, as stated by South African MNB CEO (Interview 4): ‘The bank has gone through what I call a “McDonaldization” process: You localize, there is no beef burger in India, but you don’t lose your umbilical cord’.

Last, due to the importance of Singapore’s financial hub for Indian investments, the Singaporean MNB benefits from excellent government-to-government relations, which has led to a sound relationship with the regulator, who is well-disposed towards Singaporean MNBs, and an increase in its number of branches: ‘When it comes to representing the bank’s activities in India, we can say that the regulator is very approachable, no need for any intermediary to talk to the regulator. … If your government has a good relationship with the government of India, banks are more successful’ (Interview with 2 Singaporean MNB CEO). This sentiment presents a stark contrast with the French MNB CEO’s experience: ‘It’s not easy to do business in India. The regulator is very fussy and intrusive, difficult to satisfy while the market is very competitive. Some banks give up’ (Interview 2 with French MNB CEO). That said, the French MNB can benefit from the support of home-country institutions: The French government has been very proactive in nurturing and supporting the so-called national champions in their internationalisation effort. A document tracing 150 years of the French MNB’s history in India reveals that the bank was used as the primary financial intermediary of Indo-French economic relations (e.g., development aid, military cooperation, nuclear projects). As further proof of this institutional nexus, a correspondence letter between the French MNB’s head office and the French government also reveals that the French MNB took the opportunity of French President François Mitterrand’s visit to India in 1982 to lobby Indian public authorities to open more branches across the country and to gain access to key infrastructure and energy projects.

4.3 Asset of Multinationality

By definition, the four MNBs under study have international operations, albeit to various degrees. While both the British and French MNBs have a significantly larger international footprint than Indian banks and a majority of foreign competitors (the British MNB is present in 57 countries across five continents, and the French MNB in 71 countries across five continents), the same cannot be said of the South African and Singaporean MNBs (South African MNB operates in 11 countries, mainly in Southern Africa but also in Mumbai and London; Singaporean MNB in 16 countries, mainly in the Asia–Pacific region though also in Dubai, London and Los Angeles). Nevertheless, each MNB has been able to leverage specific advantages derived from its multinationality to remain competitive in the Indian market.

The British and French MNBs have used their multinationality to strengthen their market position in India in line with their positioning as international banks. This strategy includes the following five elements:

-

1.

Both have constructed systems to facilitate circulation and transfer of knowledge across the organisation. The British MNB is characterised by extensive transfer mechanisms between India, the regional hub (e.g., Singapore) and the headquarters. For instance, our interviewee is currently working at the London-based headquarters but started his career in one of the regional offices in India before being sent to Mumbai, Singapore and then to London. The next career move could be to move back to India. In a different fashion, the French MNB relies on expatriates at key positions through a rotational system that allows for the circulation and transfer of knowledge across subsidiaries and with the headquarters. For instance, the French MNB CEO was in South Korea before being posted to Mumbai and said he was able to import digital payment technologies into the Indian subsidiary.

-

2.

Both MNBs have greater and cheaper access to the capital markets and key international currencies (dollar and euro) than many other foreign and Indian banks. The French MNB’s home market is located in the euro currency area, and the British MNB operates in Germany and France. Both MNBs have a presence in the U.S. market (e.g., the British MNB has a subsidiary in New York; the French MNB owns a retail bank in the United States). This currency argument was also highlighted by French MNB CEO: ‘Indian banks don’t have access to the money markets; therefore … they go to foreign banks when they need dollars. … We have a price advantage because they don’t have access to the money markets. … Besides, for an IPO you’ve got to find investors, and Indian banks don’t have our distribution capacities to attract foreign investors. This is an area where we fill the gap’ (Interview 1 with French MNB CEO).

-

3.

Due to their larger presence across the world (e.g., the French MNB has one of the largest international footprints across the industry; the British MNB focusses on emerging markets across Asia, Africa, the Middle East and, to a smaller extent, Latin America), both MNBs have developed a better capacity to serve Indian clients and support their internationalisation plan across the five continents, including Asia–Pacific (both MNBs have a well-developed and longstanding presence in the region, which allows them to compete with, e.g., the Singaporean MNB) and Africa (the British MNB in its current form is the product of a merger of two colonial banks: one in Asia–Pacific and one in Southern Africa).

-

4.

Their home market plays a strategic and/or significant role in regard to India’s internationalising economy and business groups. The British MNB’s home market may not be very large (it is worth noting that the bank does not have significant operations in its home market), but the UK is Europe’s main recipient of Indian FDI, and the importance of London’s financial centre makes the UK a strategic market for the Indian economy. The French MNB is part of the Single European Market; considered as a whole, this entity constitutes India’s largest trading partner. They are thus able to fetch larger volumes of business at the expense of Indian and other foreign banks that do not possess such expertise in this area of the world: ‘If an Indian business group acquires another firm in Europe, no Indian bank will be able to support the operations because you need a bank present in Europe. … Banking business requires a high level of trust and knowledge of the clients. For instance, we know Volkswagen for a very long time, unlike General Motors. Indian banks cannot do business with European companies because their knowledge of Europe is too limited. … More generally, each bank has its own geographic specialisation; no bank can cover the whole world’ (Interview 1 with French MNB CEO).

-

5.

Due to their size (as of 2020, the French MNB is the world’s 9th largest bank by asset, while the British MNB being the 44th largest bank by asset has a more moderate size) and international footprint, both MNBs have also accumulated political and economic clout and are in a position to negotiate with the local authorities in a way that other banks cannot. The British MNB’s strong (historically developed) institutional capabilities allow the bank to maintain a sizable network of branches across India (despite a tightened regulatory framework against foreign companies). In a different context, the French MNB subsidiary has been able to use its headquarters’ support to negotiate with Indian public authorities to open more branches.

While the Singaporean and South African MNBs may not benefit the same advantages of multinationality that the British and French MNBs do (e.g., regional network, restricted access to the U.S. market, small size of their respective home market), they do possess some unique multinationality advantages. Because Singapore is a hub for the fast-growing South-East Asia region, the bank can expect to fetch significant business volumes, as the Singaporean MNB CEO pointed out: ‘Our advantage is our Asian connection. We have a stronghold in ten countries in Asia and can deliver to customers over there. Very few banks have this capacity’ (Interview 1 with Singaporean MNB CEO). However, their positioning is being disputed by former colonial banks that are still deeply enmeshed in the region, such as British and French MNBs.

The South African MNB caters to the Indo-African corridor (Indian companies acquiring African companies or trade with Africa) and has an expertise in gold business that complements Indian economic specialisations very well: ‘In gold business, we still have a niche. There are gold mines in South Africa, so we have an end-to-end supply chain control. In trade business, we have Indian banks as clients and provide them with our on-the-ground African expertise, which Indian banks do not have (Interview 1 with South African MNB CEO). Nevertheless, the South African MNB’s positioning is currently being threatened for at least three reasons: competition from European MNBs in Africa, dwindling commodities price and loss of competitiveness due to South Africa’s lower sovereign rating, which has led to higher interest rates. These threats contrast sharply with the position of both the British and French MNBs, which benefit from a credible currency, stable economy and overall higher sovereign rating. The South African MNB CEO explains: ‘Even for trade with Africa, our position is not obvious as we have competitors – French banks, British banks – and commodities price are dwindling. … South Africa is now rated BBB−, similar to India. Foreign banks usually have a price advantage given that their countries of origin are better rated than India and can therefore have access to a cheaper dollar. This advantage has gone away for [South African MNB]. Indian corporates won’t come to us anymore to borrow at a cheap price’ (Interview 1 with South African MNB CEO).

4.4 Advantages Due to Externalities

Foreign firms may benefit from opportunities of sharing knowledge and best practices with other foreign firms to overcome obstacles in the host environment and enhance their competitiveness. All the four banks are located in one of the two financial districts in Mumbai (Nariman Point and Bandra Kurla Complex), which enable them to meet (as evidence of such meetings, South African MNB CEO (Interview 4) notes: ‘I met some guys working at [French MNB 2], they were smart guys’), share their respective experiences and, more generally, enjoy the benefits of regional agglomeration.

We found that the French MNB is institutionally better connected and collectively organised than its Singaporean and South African peers. The French MNB Indian subsidiary receives support at various institutional levels: not only do the French MNB subsidiary CEO meet frequently with CEOs from other French MNB subsidiaries operating in India; they meet with their European peers through a European lobbying group (European Business Group) located in Mumbai as well. French MNBs also receive support from the French public authorities (e.g., the French embassy, Indo-French Chamber of Commerce and Industry, French Advisors for External Trade – a network of businesspersons to discuss issues and best practices of doing business in India). As a result, the work of French MNB CEOs is as much that of a diplomat as a banker: ‘French bank CEOs meet very regularly. With other European banks, mostly through the European Business Group meetings: We produce a yearly brief for the public authorities. It’s like lobbying regulatory institutions. But overall, it helps to be able to exchange with your compatriots, we share regulatory information and also concerns’ (Interview 1 with French MNB CEO).

In contrast, the British, Singaporean and South African MNB subsidiaries have a more ‘go-it-alone’ approach, though the South African MNB subsidiary is a member of the Indo-African Chamber of Commerce and Industry. We observe a noticeable difference here: the British MNB – alongside other British banks – has a historical presence in India, which has resulted in the accumulation of extensive local knowledge as well as business and institutional networks. The Singaporean MNB CEO acknowledge this reality: ‘Anglo-Saxon banks [such as the British MNB] already have their own institutional channels and want to protect this advantage vis-à-vis other foreign banks’ (Interview 2 with Singaporean MNB CEO). Although neither the Singaporean and nor African MNBs have a long experience in India, they enjoy strong governmental support and excellent government-to-government relations (especially the Singaporean MNB, as stated earlier). However, they may not receive the kind of institutional and business networking support that the French MNBs do (e.g., South African MNB CEO noted: ‘We are the only African bank in India, except State Bank of Mauritius, but that’s different. It’s true it can feel lonely sometimes’). The fact that there are four French MNBs operating in Mumbai alongside many other European peers allows them to collaborate and develop a pool of shared ideas, talents and best practices.Footnote 1

Table 3 is a summary of the key findings related to MNB subsidiaries’ competitive advantages in India.

4.5 Performance of the Four MNB Subsidiaries

To shed light on the performance of each MNB subsidiary in relation to their competitive advantages, we consider four indicators related to their commercial and financial performance. First, we assess the commercial performance of the four MNB subsidiaries through the following indicators: total assets (as of March 2019) growth of assets (to avoid short-term variability, we estimate this indicator through an average over a three-year period between 2016 and 2019) and the ratio of net NPAs (as of March 2019). The NPA ratio serves as a proxy for the degree of embeddedness within local business networks; it indicates the proportion of loans issued by MNBs to local customers that are not repaid (a high [low] NPA ratio means that the subsidiary faces a higher [lower] number of nonrepaid loans). Second, financial performance is estimated by the return on assets of each subsidiary, which is a standard performance indicator in the banking industry. Again, to avoid short-term variability, we calculate an average return on assets over the same three-year period (2016–2019). Table 4 is a summary of the key performance indicators of each MNB subsidiary in India. It is also worth noting that a high NPA ratio will hurt the financial performance of the subsidiary (and vice versa).

5 Discussion of Findings

How can we explain the presence of MNBs in a competitive, regulated environment (instead of relying on a local correspondent, for instance)? What kind of competitive advantages do MNBs develop in and for the host environment? These questions are even more relevant in the context of an emerging economy characterised by the presence of certain institutional voids (e.g., little access to data and information; ineffectiveness of the judiciary system; other restrictions in the product, labour and capital markets).