Abstract

The potato (Solanum tuberosum) is one of the main sources of natural starch. In recent decades, the valorisation of potato protein that results as a by-product in the starch industry has been gaining interest as well. As potato supply is seasonal and the protein content of potatoes during long-term storage is temperature-dependent, optimal storage of potatoes is of great importance. This paper explores a model describing potato protein content during a full storage season for the Miss Malina and Agria cultivars. The model combines Michaelis-Menten protein kinetics with the Arrhenius equation. Laboratory analyses were performed to monitor the protein components in both potato cultivars and to use for estimation of the kinetic parameters. The results indicate that the two cultivars have different synthesis and degradation kinetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Nomenclature | ||

Subscript | A Arrhenius pre-exponential factor | \([\frac {1}{\text {s}}]\) |

a Air | Cp Specific heat capacity | \([\frac {\text {J}}{\text {kg} \cdot \text {K}}]\) |

E Energy | E Energy | [J] |

e Environment | Eae Activation energy | \([\frac {\text {J}}{\text {mol}}]\) |

f Final | K Michaelis-Menten constant | \([\frac {\text {g}}{\text {kg}}]\) |

p Potato | Ki Inhibition constant | \([\frac {\text {g}}{\text {kg}}]\) |

prot Protein | M Mass | [kg] |

PS Total protein (synthesis-related) | PI Protease inhibitor content | \([\frac {\text {g}}{\text {kg}}]\) |

PD Protein (degradation-related) | Pat Patatin content | \([\frac {\text {g}}{\text {kg}}]\) |

PI Protease inhibitor | R Universal gas constant | \([\frac {\text {J}}{\text {K} \cdot \text {mol}}]\) |

(synthesis-related) | ||

Parameters | TP Total protein content | \([\frac {\text {g}}{\text {kg}}]\) |

𝜗 Parameter vector | t Time | [s] |

ρ Density \([\frac {\text {kg}}{\text {m}^{3}}]\) | T Temperature | [Kelvin] |

V Volume | [m3] |

Introduction

One of the most important crops worldwide is the potato (Solanum tuberosum), accounting for about 45% of the global tuber crop production (WCRTC 2016). Potato crops are not only grown for consumption, but also for starch production, with the starch extraction process yielding protein-rich waste water (Løkra and Strætkvern 2009). The potato protein solution has been the subject of many studies to determine its composition and functional properties (Kapoor et al. 1975; Holm and Eriksen 1980; Ralet and Guéguen 2000). The total soluble protein content in the potato juice consists mainly of three groups: patatin (40–60%), protease inhibitors (20–30%) and other (high-molecular-weight) proteins (Pots et al. 1999). Potatoes are a superior protein source relative to other vegetables and cereals because of their high nutritional quality (Seo et al. 2014). Therefore, potato proteins, like Solanic, are also used in food applications (Alting et al. 2011; Boland et al. 2013). In addition to the present food application and feed supplements, potato proteins are of great potential in specific biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications (Kong et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2017).

Protein quality is therefore becoming increasingly important in the industrial production of potato proteins (Grommers and van der Krogt 2009). The quality and amount of proteins in potatoes are determined by the conditions during the growing season. As potatoes are a seasonal crop, storage of potatoes is essential to be able to provide potatoes all year round. The economic optimum of potato protein production depends on the proteins formed during growth, the capacity of the processing industry, and any protein losses or synthesis during storage.

During long-term storage, both protein degradation and protein synthesis take place continuously and, as previously found, total soluble protein levels fluctuate (Nowak 1977; Brasil et al. 1993; Brierley et al. 1996). The dynamics and fluctuations of the protein content vary, especially between different potato cultivars. As Table 1 shows, some long-term storage studies found an increase in protein content (Brierley et al. 1996, 1997) or a constant protein content (Mazza 1983; Blenkinsop et al. 2002), while others reported a decrease (Nowak 1977; Kumar and Knowles 1993). Notice from Table 1 that a wide range of protein contents is found. For instance, the cultivar Russet Burbank shows protein contents that fluctuate within two different studies, while for the cultivar Pentland Dell, similar contents were found in two different studies. The studies listed in Table 1 and additionally, the study by Brasil et al. (1993), showed that, besides on cultivar, the protein content development also depends on storage temperature.

This means that a dedicated storage strategy is needed to yield potatoes with high protein levels for industrial extraction. As high protein levels are associated with low levels of free amino acids (Brierley et al. 1996), which are involved in the Maillard browning reaction (Khanbari and Thompson 1993), protein-rich potatoes are also useful for frying. Optimal storage obviously depends on the eventual use of the potatoes. However, neither a mathematical model that describes the dependence of potato proteins on storage temperature nor a corresponding control strategy are currently available.

We have therefore carried out a study to investigate and model the development of potato protein content in potatoes in a large-scale bulk storage facility. We measured potato protein content throughout a single harvesting and storage season (2015–2016) and used Michaelis-Menten kinetics combined with the Arrhenius equation to describe how protein content depends on storage temperature. This combination is capable of capturing the temperature dependence of enzyme activity accurately (Davidson et al. 2012).

The next section of this paper describes the materials and methods used for protein extraction and the modelling procedure. Section “Results” presents the results of the protein content measurements, parameter analyses and model simulations. Section “Discussion” contains the discussion of the results and we present our conclusions in Section “Conclusions”.

Material and Methods

Tuber Storage and Preparation

Potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers of two different cultivars (Agria and Miss Malina) were obtained from storage facilities at local local farms in Flevoland, the Netherlands. All tubers were stored at 6 to 15 °C and 90 to 95% relative humidity. Weekly and in duplicate, five tubers from each cultivar were taken from storage, peeled and chopped, and pieces of several tubers with a combined weight of 200 grams were juiced. After juicing, the pulp left in the juicer was flushed three times with approximately 100 mL cold water (Sowokinos 1978) until we obtained 500 mL diluted potato juice. We waited 2 min between these three flushing steps. Of the resulting potato juice, 2 mL was frozen at –20 °C and stored until protein determination.

Protein Determination

Total soluble protein of the stored potato tubers was determined by an adaptation of the Coomassie Blue dye-binding assay of Bradford (1976), with bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich) as a standard. The samples were diluted twice in Tris-HCl with a pH value of 7.0 and containing 0.1 mM dithiothreitol (hereafter referred to as Tris buffer), so the final concentration was in the range of the protein standards. Next, we filtered the diluted protein samples through a 0.45 m pore size membrane. The assay was carried out by adding 1.5 mL of Bradford Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) to 0.05 mL of sample. After 25 min, we measured the absorbance at 595 nm in a spectrophotometer and compared this with the absorbance of the protein standard.

The fractions of patatin and protease inhibitors were determined by gel filtration as done before by Brierley et al. (1996). We diluted the protein samples five times, again in Tris buffer, and filtered them through a 0.2 m pore size membrane. We used a Biosep SEC-s2000 gel filtration column (Phenomenex) to separate the protein fractions. The patatin fraction was identified by comparison with a 45-kDa glycoprotein standard (Phenomenex), and the area of the patatin peak was compared with the total peak area to give its proportion. We identified the protease inhibitor fraction by comparison with a 15-kDa protein standard, and took the two peaks around this molecular weight (15 to 21 kDa). The area of these peaks was then compared with the total peak area to give the proportion of protease inhibitors.

Protein Model

Both protein synthesis and degradation have been the subject of many studies investigating either their mechanics or their kinetics. While some researchers have modelled the rate of protein synthesis by describing the entire process of gene expression and subsequent protein synthesis by ribosomes (von Heijne et al. 1987; Antoun et al. 2006), others have tried approaching synthesis by using Michaelis-Menten kinetics for the entire process (Lancelot et al. 1986; Danfær 1991). Several studies have found that protein degradation can be described by Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Hersch et al. 2004; Grilly et al. 2007; Gérard et al. 2016). However, there are also some indications that protein turnover is a temperature-dependent process (Strnadova et al. 1986). This can be incorporated in each term by combining the Michaelis-Menten kinetic model with the Arrhenius model, as reported by Davidson et al. (2012). The major protein components of potatoes (patatin, protease inhibitors, total protein content) can be described by mathematical models of protein synthesis and degradation with the aforementioned kinetics. The following model describes the temperature-dependent dynamics of total protein content (TP), protease inhibitors (PI) and patatin content (Pat) in a potato.

The model takes the temperature inside the potato as uniformly distributed and equal to the temperature inside the storage facility. The model also assumes a uniform protein distribution throughout a single potato tuber, which means that the concentration of each component does not depend on the location in the tuber. With regard to protein content, the model considers the potato a closed system that does not interact with its environment. This means that no excretion or uptake of proteins or amino acids takes place. Consequently, the rates of change for each component are the sums of their synthesis and degradation rates and do not depend on migration of components. As patatin cannot be synthesised during storage (see, e.g. Racusen 1983; Paiva et al. 1983; Rosahl et al. 1986; Bárta and Bártová 2008), its rate of change is only dependent on its degradation. We also assumed that each component degrades at the same rate and with the same affinity constant (KPD).

As competitive inhibition is the most common mechanism of protease inhibition in plants (Ryan 1990), it was assumed to be the mechanism of action. We therefore included the term \((1+\frac {PI}{K_{i}})\) in the degradation terms to incorporate competitive inhibition of proteases by protease inhibitors, as used before in Michaelis-Menten models with inhibition (Nxumalo et al. 1998).

Parameter Estimation

To use the protein model as represented by Eqs. 1–3 for simulation, the parameters first need to be estimated. We used the experimental data described in Sections “Tuber Storage and Preparation” and “Protein Determination” for the estimation of the kinetic parameters. As Eqs. 1–3 are non-linear in the kinetic parameters, we applied the non-linear least squares algorithm in Matlab lsqnonlin. This function finds the minimum of the sum of squares of the residuals between measured and predicted TP, PI and Pat contents, by changing the values in the parameter vector \(\vartheta \triangleq [A_{PS}~ A_{PD}~ A_{PI}~ E_{PS}~ E_{PD}~ E_{PI}~ K_{PD}~ K_{i} ]^{T} \).

Results

Protein Content

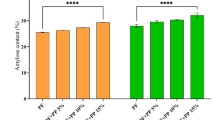

It is known that different cultivars show different temporal trends regarding both total soluble protein as well as the individual fractions (see Table 1). In our study, the protein content of the cultivar Miss Malina appeared to decline during storage. The patatin and the protease inhibitor fractions exhibited similar behaviours, as shown in the left panels of Fig. 1. After the first 7 weeks during which the temperature decreased gradually, there were 10 weeks during which the temperature was kept constant at 8 °C. After week 27, there were sudden changes, but these temperature changes at the end of the storage season were not reflected in the protein contents.

Measured protein content and temperature for Miss Malina (MM) in the left panel, and for Agria (A) in the right panel. From top to bottom, total protein, patatin and protease inhibitor contents are shown as well as storage temperature, with error bars for the three protein contents as a result of duplicate samples

The total protein level of the cultivar Agria appeared to fluctuate more, and increased slightly at the beginning of the storage period, again coinciding with a gradual lowering of the temperature; see right panels in Fig. 1. While the patatin values fluctuated after that initial period, these fluctuations occurred within a fairly constant band. The protease inhibitor content showed a clear decrease from approximately 0.68 [g/kg FW] to around 0.56 [g/kg FW]. As for Miss Malina, the temperature initially decreased until it reached the desired constant value. For Agria, this constant temperature was 6.5 °C and there were no changes at the end.

Parameter Analysis

An identifiability analysis showed that the model as proposed in Eqs. 1–3 is unidentifiable, so it is not possible to estimate the model parameters individually. As a remedy, we propose the following parameter estimation procedure with the following three stages:

-

I.

Make the system linear in the parameters by setting EPS = EPD = EPI = KPD = 0. Consequently, a linear regression model results, from which APS, APD and API can be identified.

-

II.

Fix the parameter estimates of APS, APD and APi found in stage I. Use a non-linear least squares algorithm to estimate the remaining set of parameters. To limit the number of parameters in this non-linear estimation step, set EPS = EPD = EPI = E, and thus estimate E, KPD and Ki.

In the results of stage I, we found that some of the parameter estimates of APS, APD and APi had negative values and thus were not physically interpretable. Stage II resulted in the finding that E and Ki were insensitive parameters. To deal with our first finding of negative estimates, while retaining the possibility of different slopes in each of the measured time series, we chose to split KPD into KTP, KPI and KPat. On the basis of the results from I and II, we fixed both E and Ki.

-

III.

Iteratively process the following steps: (i) solve the linear regression problem by setting E = 1e3 and Ki = 0.1 found as appropriate estimates in stage II and use the initial guess KTP = KPI = KPat = 1 to find parameter estimates for APS, APD and APi, (ii) use a non-linear least squares algorithm to find KTP, KPI and KPat, (iii) evaluate the accuracy of the estimates and adapt the parameter estimates of KTP, KPI and KPat in (i), then repeat steps (ii) and (iii) until convergence.

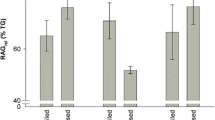

We found different parameter sets for each potato cultivar (Table 2). As mentioned in Section “Protein Content”, the cultivar Miss Malina experienced a slight decrease in all protein fractions. This decrease is also visible in the predicted model outputs using the parameter values from Table 2; see the left panel of Fig. 2. For the cultivar Agria, only the protease inhibitors decreased; total protein content increased slightly and the patatin content was more or less constant, which was also predicted by the model using the parameter values from Table 2; see the right panel of Fig. 2. For both cultivars, the model responses do not follow the fluctuations in the data, but provide reasonable overall fits.

The parameter estimation revealed the activation energy Ea as an insensitive parameter. This low sensitivity is in line with the measurement data, showing no relationship between temperature fluctuations during storage and changes in protein content. The estimate of KPat for the cultivar Agria is much higher than the estimate of KPat for the cultivar Miss Malina. This difference could already have been deduced from the measured patatin content, as this was almost constant for the cultivar Agria, meaning that KPat was very high, while the cultivar Miss Malina displayed a decreasing patatin content.

Discussion

Protein synthesis is a complicated process, which can briefly be summed up as follows. In order for protein synthesis to occur, genes first need to be expressed, resulting in RNA strands. These strands have to make their way out of the cell nucleus to ribosomes in the cytoplasm. Protein synthesis then proceeds by reading the RNA strand and constructing a string of amino acids that together form the protein. Mathematical modelling of detailed protein synthesis has been carried out before for prokaryotic organisms (Drew 2001), but still remains to be done for higher organisms such as plants or mammals.

In the presented work, a simplified model for potato protein during long-term storage is presented, on basis of the protein turnover and storage temperature. From literature (Table 1), it was seen that the protein content can increase, remain constant or decrease during long-term storage, what was also seen in the experimental data.

In our experiments, we observed a decreasing total protein content for Miss Malina and a slightly increasing total protein content for Agria. The data for both Miss Malina and Agria display fluctuations over time in total protein, protease inhibitors and patatin content. The three components appear strongly correlated. Previous studies had a significantly lower sampling frequency than the sampling frequency of 1 week applied in this study; we have not been able to find any studies reporting fluctuations within a single week. From our experimental data, we are unable to conclude whether the protein content in the potato fluctuates as fast as seen in the measured data or whether these fluctuations are a result of sampling and measurement errors.

Furthermore, the protein determination method that was used in this article may have been influenced by the presence of phenolic compounds in the potato tubers (Mattoo et al. 1987). Crude homogenates of potato can contain significant amounts of phenols (Ezekiel et al. 2013), which can interfere with dye-binding to the protein. This may result in underestimation of the protein content. Using the newly developed automated Sprint Rapid Protein Analyzer method in combination with the Kjeldahl method for total nitrogen determination can result in more accurate measurement results, while simultaneously increasing the speed of the analysis (Nielsen 2017).

For the modelling of the protein content during long-term storage, we assumed that the protein turnover has a significant effect on protein dynamics. The total protein turnover consists of the sum of total protein synthesis and degradation and strongly depends on temperature (see, e.g. Brasil et al. 1993). We therefore modelled the synthesis and degradation processes by using temperature-dependent Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The temperature dependence was expressed in terms of the Arrhenius equation.

Our parameter estimation results, however, showed that the activation energy E is larger than zero, but it could only be estimated from the data with a large uncertainty. Furthermore, for the cultivar Miss Malina, significant changes in temperature at the end of the storage season did not lead to changes in the protein content. Consequently, E was fixed at 103 J/mol and thus the factor e−E/RT is approximately equal to 0.65. This choice of E directly affects the estimated values of APD, API and APat, which could not be estimated very accurately either (Table 2). We were able to estimate the affinity constants KTP, KPI and KPat for the cultivar Miss Malina accurately (Table 2). For the cultivar Agria, only KPat could not be accurately estimated, as the corresponding patatin data did not show a clear increase or decrease.

Conclusions

Our study appears to show that the protein content of potatoes depends on cultivar and possibly less straightforwardly on temperature. We propose that the total protein, protease inhibitors and patatin contents can be modelled using Michaelis-Menten kinetics, in combination with the Arrhenius equation. The proposed model provides insight into the dynamic behaviour of the protein content of potatoes in storage. However, more experimental research is needed to be able to estimate the model parameters accurately, except for the affinity constants, and to validate the model for multiple storage seasons. For a further understanding of protein turnover in potatoes, dedicated experiments for different cultivars are needed to find explicit temperature effects on the synthesis and degradation of proteins. Once these relationships become available, the protein model (Eqs. 1–3) can be integrated into the potato storage model (Grubben and Keesman 2019) and possibly extended with the sugar model as presented by Grubben et al. (2019).

References

Alting AC, Pouvreau L, Giuseppin MLF, van Nieuwenhuijzen NH (2011) Potato proteins. In: Handbook of food proteins. Woodhead Publishing

Antoun A, Pavlov MY, Lovmar M, Ehrenberg M (2006) How initiation factors tune the rate of initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria. EMBO J 25 (11):2539–2550

Bárta J, Bártová V (2008) Patatin, the major protein of potato (Solanum tuberosum l.) tubers, and its occurrence as genotype effect: processing versus table potatoes. Czech J Food Sci 26(5):347–359

Blenkinsop RW, Copp LJ, Yada RY, Marangoni AG (2002) Changes in compositional parameters of tubers of potato (Solanum tuberosum) during low-temperature storage and their relationship to chip processing quality. J Agric Food Chem 50(16):4545–4553

Boland MJ, Rae AN, Vereijken JM, Meuwissen MPM, Fischer ARH, van Boekel MAJS, Rutherfurd SM, Gruppen H, Moughan PJ, Hendriks WH (2013) The future supply of animal-derived protein for human consumption. Trends Food Sci Technol 29:62–73

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72(1–2):248–254

Brasil PJ, César AB, Marcio HP (1993) Effects of different storage temperatures on protein quantities of potato tubers. Rev Bras Fisiol Veg 5(2):167–170

Brierley ER, Bonner PLR, Cobb AH (1996) Factors influencing the free amino acid content of potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers during prolonged storage. J Sci Food Agric 70:515–525

Brierley ER, Bonner PLR, Cobb AH (1997) Aspects of amino acid metabolism in stored potato tubers (cv. Pentland Dell). Plant Sci 127(1):17–24

Danfær A (1991) Mathematical modelling of metabolic regulation and growth. Livest Prod Sci 27:1–18

Davidson EA, Samanta S, Caramori SS, Savage K (2012) The dual Arrhenius and Michaelis-Menten kinetics model for decomposition of soil organic matter at hourly to seasonal time scales. Glob Chang Biol 18(1):371–384

Drew DA (2001) A mathematical model for prokaryotic protein synthesis. Bull Math Biol 63:329–351

Ezekiel R, Singh N, Sharma S, Kaur A (2013) Beneficial phytochemicals in potato - a review. Food Res Int 50:487–496

Gérard C, Gonze D, Goldbeter A (2016) Dependence of the period on the rate of protein degradation in minimal models for circadian oscillations. Phil Trans R Soc A 367:4665–4683

Grilly C, Stricker J, Pang WL, Bennett MR, Hasty J (2007) A synthetic gene network for tuning protein degradation in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Syst Biol 3:127

Grommers HE, van der Krogt DA (2009) Chemistry and technology: starch. Academic Press

Grubben N, Keesman K (2019) A spatially distributed physical model for dynamic simulation of ventilated agro-material in bulk-storage facilities. Comput Electron Agri 157:380–391

Grubben NLM, Witte SC, Keesman KJ (2019) Postharvest quality development of frying potatoes in a large-scale bulk storage facility. Postharvest Biol Technol 149:90–100

Hersch GL, Bakker TA, Bakker RT (2004) Sspb delivery of substrates for clpxp proteolysis probed by the design of improved degradation tags. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(33):12136–41

Holm F, Eriksen S (1980) Emulsifying properties of undenatured potato protein concentrate. Int J Food Sci Technol 15(1):71–83

Kapoor AC, Desborough SL, Li PH (1975) Potato tuber proteins and their nutritional quality. Potato Res 18(3):469–478

Khanbari OS, Thompson AK (1993) Effects of amino acids and glucose on the fry colour of potato crisps. Potato Res 36(4):359–364

Kong X, Kong L, Ying Y, Hua Y, Wang L (2015) Recovering proteins from potato juice by complexation with natural polyelectrolytes. Int J Food Sci Technol 50:2160–2167

Kumar GNM, Knowles NR (1993) Age of potato seed-tubers influences protein synthesis during sprouting. Physiologia plantarum 89:262–270

Lancelot C, Mathot S, Owens N (1986) Modelling protein synthesis, a step to an accurate estimate of net primary production: phaeocystis pouchetii colonies in belgian coastal waters. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 32:193–202

Løkra S, Strætkvern KO (2009) Industrial proteins from potato juice. A review. Food 3(1):88–95

Mattoo RL, Ishaq M, Saleemuddin M (1987) Protein assay by coomassie brilliant blue g-250-binding method is unsuitable for plant tissues rich in phenols and phenolases. Anal Biochem 163(2):376–384

Mazza G (1983) Correlations between quality parameters of potatoes during growth and long-term storage. Am Potato Res 60(3):145–159

Nielsen SS (ed.) (2017) Food analysis, Food Science Texts Series. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45776-5

Nowak J (1977) Biochemical changes in stored potato-tubers with different rest periods.1. Influence of storage temperature and isopropyl phenylcarbamates (ipc and cipc) on protein changes. Int J Plant Physiol 81(2):113–124

Nxumalo F, Glover NR, Tracey AS (1998) Kinetics and molecular modelling studies of the inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases by n,n-dimethylhydroxylamine complexes of vanadium. J Biol Inorg Chem 3(5):534–542

Paiva E, Lister RM, Park WD (1983) Induction and accumulation of major tuber proteins of potato in stems and petioles. Plant Physiol 71(1):161–168

Pots AM, Gruppen H, van Diepenbeek R, van der Lee JJ, van Boekel MAJS, Wijngaards G, Voragen AGJ (1999) The effect of storage of whole potatoes of three cultivars on the patatin and protease inhibitor content; a study using capillary electrophoresis and maldi-tof mass spectrometry. J Sci Food Agric 79:1557–1564

Racusen D (1983) Occurrence of patatin during growth and storage of potato turbers. Can J Botany 61:370–373

Ralet MC, Guéguen J (2000) Fractionation of potato proteins: solubility, thermal coagulation and emulsifying properties. LWT - Food Sci Technol 33(5):380–387

Rosahl S, Schmidt R, Schell J, Willmitzer L (1986) Isolation and characterization of a gene from Solanum tuberosum encoding patatin, the major storage protein of potato tubers. Mol Gen Genet 203(2):214–220

Ryan CA (1990) Protease inhibitors in plants: genes for improving defenses against insects and pathogens. Ann Rev Phytopathol 28(1):425–449

Seo S, Karboune S, Archelas A (2014) Production and characterisation of potato patatingalactose, galactooligosaccharides, and galactan conjugates of great potential as functional ingredients. Food Chem 158:480–489

Sowokinos JR (1978) Relationship of harvest sucrose content to processing maturity and storage life of potatoes. Am Potato J 55:33–344

Strnadova M, Prasad R, Kučerovcá H, Chaloupka J (1986) Effect of temperature on growth and protein turnover in Bacillus megaterium. J Basic Microbiol 26(5):289–298

von Heijne G, Blomberg C, Liljenström H (1987) Theoretical modelling of protein synthesis. J Theor Biol 125(1):1–14

WCRTC (2016) World congress on root and tuber crops, participants gcp21. http://www.gcp21org/wcrtc/. Accessed on may 2018

Zhang DQ, Mu TH, Sun HN, Chen JW, Zhang M (2017) Comparative study of potato protein concentrates extracted using ammonium sulfate and isoelectric precipitation. Int J Food Properties 20(9):2113–2127

Funding

This work is part of a research project carried out at and financially supported by Omnivent Techniek B.V. in the Netherlands, an international specialist in the storage of foods like potatoes, onions, carrots and other fruits and vegetables. This research project will provide Omnivent Techniek B.V. with more information and knowledge on how storage and control strategies influence potato quality and storage losses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grubben, N.L.M., van Heeringen, L. & Keesman, K.J. Modelling Potato Protein Content for Large-Scale Bulk Storage Facilities. Potato Res. 62, 333–344 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-019-9414-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-019-9414-7