Abstract

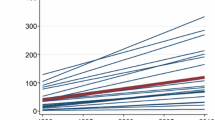

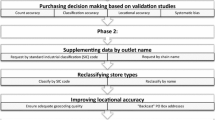

Retail environments, such as healthcare locations, food stores, and recreation facilities, may be relevant to many health behaviors and outcomes. However, minimal guidance on how to collect, process, aggregate, and link these data results in inconsistent or incomplete measurement that can introduce misclassification bias and limit replication of existing research. We describe the following steps to leverage business data for longitudinal neighborhood health research: re-geolocating establishment addresses, preliminary classification using standard industrial codes, systematic checks to refine classifications, incorporation and integration of complementary data sources, documentation of a flexible hierarchical classification system and variable naming conventions, and linking to neighborhoods and participant residences. We show results of this classification from a dataset of locations (over 77 million establishment locations) across the contiguous U.S. from 1990 to 2014. By incorporating complementary data sources, through manual spot checks in Google StreetView and word and name searches, we enhanced a basic classification using only standard industrial codes. Ultimately, providing these enhanced longitudinal data and supplying detailed methods for researchers to replicate our work promotes consistency, replicability, and new opportunities in neighborhood health research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The detailed methods, corresponding code or syntax, and reports summarizing aggregated data developed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request, subject to limits specified in data use or licensing agreements.

Abbreviations

- D & B:

-

Dun and Bradsteet

- GIS:

-

Geographic Information System

- JCC:

-

Jewish Community Centers

- NAICS:

-

North American Industry Classification System

- NETS:

-

National Establishment Time Series

- R & I:

-

Restaurants & Institutions

- SIC:

-

Standard Industrial Classification

- YMCA :

-

Young Men’s Christian Associations

- ZCTA:

-

Zip Code Tabulation Area

References

Arcaya MC, Tucker-Seeley RD, Kim R, Schnake-Mahl A, So M, Subramanian S. Research on neighborhood effects on health in the United States: a systematic review of study characteristics. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:16–29.

Roux AVD, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1186(1):125–45.

Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Neighborhoods and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:307–26.

Sarkar C, Webster C. Healthy cities of tomorrow: the case for large scale built environment-health studies. J Urban Health. 2017;94(1):4–19.

Schulz A, Northridge ME. Social determinants of health: implications for environmental health promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(4):455–71.

Northridge ME, Sclar ED, Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health. 2003;80(4):556–68.

McMichael AJ. Prisoners of the proximate: loosening the constraints on epidemiology in an age of change. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(10):887–97.

Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med (1982). 2002;55(1):125–39.

Charreire H, Casey R, Salze P, Simon C, Chaix B, Banos A, et al. Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: a methodological review. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1773–85.

Cobb LK, Appel LJ, Franco M, Jones-Smith JC, Nur A, Anderson CA. The relationship of the local food environment with obesity: a systematic review of methods, study quality, and results. Obesity. 2015;23(7):1331–44.

Oldenburg RJ. Our vanishing third places. The Planning Commissioners Journal. 1997;25(4):6–10.

Mehta V, Bosson JK. Third places and the social life of streets. Environ Behav. 2009;42(6):779–805.

Oldenburg R The great good place: cafes, coffee shops, bookstores, bars, hair salons, and other hangouts at the heart of a community. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press; 1999.

Oldenburg R Celebrating the third place: inspiring stories about the great good places at the heart of our communities. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press; 2001.

Klinenberg E. Heat wave: a social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2015.

Klinenberg E. Palaces for the people: how social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. New York City, NY: Broadway Books; 2018.

Gullón P, Lovasi GS. Designing healthier built environments. Oxford, UK: Neighborhoods and Health 2018:219.

Saelens BE, Handy SL. Built environment correlates of walking: a review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S550–66.

Berchuck SI, Warren JL, Herring AH, Evenson KR, Moore KAB, Ranchod YK, et al. Spatially modelling the association between access to recreational facilities and exercise: the ‘Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis’. J R Stat Soc: Series A (Statistics in Society). 2016;179(1):293–310.

Kaufman TK, Rundle A, Neckerman KM, Sheehan DM, Lovasi GS, Hirsch JA. Neighborhood recreation facilities and facility membership are jointly associated with objectively measured physical activity. J Urban Health 2019:1–13.

Park Y, Neckerman K, Quinn J, Weiss C, Jacobson J, Rundle A. Neighbourhood immigrant acculturation and diet among Hispanic female residents of New York City. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(9):1593–600.

Rummo PE, Meyer KA, Boone-Heinonen J, Jacobs DR Jr, Kiefe CI, Lewis CE, et al. Neighborhood availability of convenience stores and diet quality: findings from 20 years of follow-up in the coronary artery risk development in young adults study. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):e65–73.

Fleischhacker SE, Evenson KR, Rodriguez DA, Ammerman AS. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e460–71.

Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1172–87.

Moore KA, Hirsch JA, August C, Mair C, Sanchez BN, Roux AVD. Neighborhood social resources and depressive symptoms: longitudinal results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Urban Health. 2016;93(3):572–88.

Johnson DA, Hirsch JA, Moore KA, Redline S, Diez Roux AV. Associations between the built environment and objective measures of sleep: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(5):941–50.

Mair C, Roux AD, Golden SH, Rapp S, Seeman T, Shea S. Change in neighborhood environments and depressive symptoms in New York City: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health Place. 2015;32:93–8.

Hirsch JA, Moore KA, Clarke PJ, Rodriguez DA, Evenson KR, Brines SJ, et al. Changes in the built environment and changes in the amount of walking over time: longitudinal results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(8):799–809.

Cerin E, Nathan A, Van Cauwenberg J, Barnett DW, Barnett A. The neighbourhood physical environment and active travel in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):15.

Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking: review and research agenda. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):67–76.

Meyer KA, Boone-Heinonen J, Duffey KJ, Rodriguez DA, Kiefe CI, Lewis CE, et al. Combined measure of neighborhood food and physical activity environments and weight-related outcomes: the CARDIA study. Health Place. 2015;33:9–18.

Hirsch JA, Moore KA, Barrientos-Gutierrez T, Brines SJ, Zagorski MA, Rodriguez DA, et al. Built environment change and change in BMI and waist circumference: multi-ethnic s tudy of a therosclerosis. Obesity. 2014;22(11):2450–7.

Lee H. The role of local food availability in explaining obesity risk among young school-aged children. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(8):1193–203.

Zick CD, Smith KR, Fan JX, Brown BB, Yamada I, Kowaleski-Jones L. Running to the store? The relationship between neighborhood environments and the risk of obesity. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(10):1493–500.

Thornton LE, Pearce JR, Kavanagh AM. Using geographic information systems (GIS) to assess the role of the built environment in influencing obesity: a glossary. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):71.

Auchincloss AH, Roux AVD, Brown DG, Erdmann CA, Bertoni AG. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and their association with insulin resistance. Epidemiology. 2008;19:146–57.

Auchincloss AH, Roux AVD, Mujahid MS, Shen M, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1698–704.

Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR, Sánchez BN, Moore K, et al. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood physical and social environments and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1311–20.

Dubowitz T, Ghosh-Dastidar M, Eibner C, Slaughter ME, Fernandes M, Whitsel EA, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative: the food environment, neighborhood socioeconomic status, BMI, and blood pressure. Obesity. 2012;20(4):862–71.

Kaiser P, Diez Roux AV, Mujahid M, Carnethon M, Bertoni A, Adar SD, et al. Neighborhood environments and incident hypertension in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183(11):988–97.

Chandrabose M, Rachele J, Gunn L, et al. Built environment and cardio-metabolic health: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obes Rev. 2019;20(1):41–54.

Roux AVD, Mujahid MS, Hirsch JA, Moore K, Moore LV. The impact of neighborhoods on CV risk. Glob Heart. 2016;11(3):353–63.

Braun LM, Rodríguez DA, Evenson KR, Hirsch JA, Moore KA, Roux AVD. Walkability and cardiometabolic risk factors: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Health Place. 2016;39:9–17.

Goh CE, Mooney SJ, Siscovick DS, Lemaitre RN, Hurvitz P, Sotoodehnia N, et al. Medical facilities in the neighborhood and incidence of sudden cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2018;130:118–23.

Rosso AL, Grubesic TH, Auchincloss AH, Tabb LP, Michael YL. Neighborhood amenities and mobility in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(5):761–9.

Yen IH, Michael YL, Perdue L. Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):455–63.

Chaudhury H, Campo M, Michael Y, Mahmood A. Neighbourhood environment and physical activity in older adults. Soc Sci Med. 2016;149:104–13.

Lamichhane AP, Warren JL, Peterson M, Rummo P, Gordon-Larsen P. Spatial-temporal modeling of neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics and food stores. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;181(2):137–50.

Rummo PE, Guilkey DK, Ng SW, Popkin BM, Evenson KR, Gordon-Larsen P. Beyond supermarkets: food outlet location selection in four US cities over time. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(3):300–10.

Hirsch JA, Green GF, Peterson M, Rodriguez DA, Gordon-Larsen P. Neighborhood sociodemographics and change in built infrastructure. J Urban: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability. 2017;10(2):181–97.

Neumark D, Zhang J, Wall B. Employment dynamics and business relocation: new evidence from the National Establishment Time Series. In: Aspects of worker well-being. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2007:39–83.

Neumark D, Zhang J, Wall B. Where the jobs are. Acad Manag Perspect. 2006;20(4):79–94.

Rummo PE, Hirsch JA, Howard AG, Gordon-Larsen P. In which neighborhoods are older adult populations expanding? Sociodemographic and built environment characteristics across neighborhood trajectory classes of older adult populations in four U.S. cities over 30 years. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2016;2:2333721416655966.

Wilkins EL, Morris MA, Radley D, Griffiths C. Using geographic information systems to measure retail food environments: discussion of methodological considerations and a proposed reporting checklist (geo-FERN). Health Place. 2017;44:110–7.

Kaufman TK, Sheehan DM, Rundle A, Neckerman KM, Bader MDM, Jack D, et al. Measuring health-relevant businesses over 21 years: refining the National Establishment Time-Series (NETS), a dynamic longitudinal data set. BMC Research Notes. 2015;8(1):507.

Auchincloss AH, Moore KAB, Moore LV, Diez Roux AV. Improving retrospective characterization of the food environment for a large region in the United States during a historic time period. Health Place. 2012;18(6):1341–7.

Wang MC, Gonzalez AA, Ritchie LD, Winkleby MA. The neighborhood food environment: sources of historical data on retail food stores. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3(1):15.

Rundle AG, Chen Y, Quinn JW, et al. Development of a neighborhood walkability index for studying neighborhood physical activity contexts in communities across the US over the past three decades. J Urban Health 2019:1–8.

Fleischhacker SE, Evenson KR, Sharkey J, Pitts SBJ, Rodriguez DA. Validity of secondary retail food outlet data: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):462–73.

Bader MD, Ailshire JA, Morenoff JD, House JS. Measurement of the local food environment: a comparison of existing data sources. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(5):609–17.

McCormack GR, Shiell A. In search of causality: a systematic review of the relationship between the built environment and physical activity among adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):125.

Ding D, Gebel K. Built environment, physical activity, and obesity: what have we learned from reviewing the literature? Health Place. 2012;18(1):100–5.

Lovasi GS, Grady S, Rundle A. Steps forward: review and recommendations for research on walkability, physical activity and cardiovascular health. Public Health Rev. 2011;33(2):484–506.

Forsyth A, Lytle L, Riper DV. Finding food: issues and challenges in using geographic information systems to measure food access. J Transp Land Use. 2010;3(1):43–65.

Ni Mhurchu C, Vandevijvere S, Waterlander W, Thornton LE, Kelly B, Cameron AJ, et al. Monitoring the availability of healthy and unhealthy foods and non-alcoholic beverages in community and consumer retail food environments globally. Obes Rev. 2013;14(S1):108–19.

Dun & Bradstreet Corp. Dun & Bradstreet Corp/NW 2016 Annual Report Form (10-K). 2017; https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1115222/000111522217000007/a201610-k.htm. Accessed September 13, 2017.

Walls D. National establishment time-series (NETS) database: 2013 database description. 2015. Denver, CO.

Hoehner CM, Schootman M. Concordance of commercial data sources for neighborhood-effects studies. J Urban Health. 2010;87(4):713–25.

NAICS Association. NAICS to SIC crosswalk. 2020; https://www.naics.com/naics-to-sic-crosswalk-2/. Accessed July 17, 2020.

Jones KK, Zenk SN, Tarlov E, Powell LM, Matthews SA, Horoi I. A step-by-step approach to improve data quality when using commercial business lists to characterize retail food environments. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):35.

Rundle A, Neckerman Kathryn M, Freeman L, et al. Neighborhood food environment and walkability predict obesity in New York City. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(3):442–7.

James P, Berrigan D, Hart JE, Aaron Hipp J, Hoehner CM, Kerr J, et al. Effects of buffer size and shape on associations between the built environment and energy balance. Health Place. 2014;27:162–70.

Feng J, Glass TA, Curriero FC, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. The built environment and obesity: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. Health Place. 2010;16(2):175–90.

Richardson AS, Meyer KA, Howard AG, Boone-Heinonen J, Popkin BM, Evenson KR, et al. Multiple pathways from the neighborhood food environment to increased body mass index through dietary behaviors: a structural equation-based analysis in the CARDIA study. Health Place. 2015;36:74–87.

Hirsch JA, Grengs J, Schulz A, Adar SD, Rodriguez DA, Brines SJ, et al. How much are built environments changing, and where?: patterns of change by neighborhood sociodemographic characteristics across seven US metropolitan areas. Soc Sci Med. 2016;169:97–105.

Berger N, Kaufman TK, Bader MD, et al. Disparities in trajectories of changes in the unhealthy food environment in New York city: a latent class growth analysis, 1990–2010. Soc Sci Med. 2019;2019:112362.

Finlay J, Esposito M, Kim MH, Gomez-Lopez I, Clarke P. Closure of ‘third places’? Exploring potential consequences for collective health and wellbeing. Health Place. 2019;60:102225.

Bezruchka S. The effect of economic recession on population health. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181(5):281–5.

Katikireddi SV, Niedzwiedz CL, Popham F. Trends in population mental health before and after the 2008 recession: a repeat cross-sectional analysis of the 1991–2010 Health Surveys of England. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5):e001790.

Nandi A, Charters TJ, Strumpf EC, Heymann J, Harper S. Economic conditions and health behaviours during the ‘Great Recession’. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(12):1038–46.

Hirsch JA, Winters M, Clarke P, McKay H. Generating GPS activity spaces that shed light upon the mobility habits of older adults: a descriptive analysis. Int J Health Geogr. 2014;13(1):51.

Chen X, Kwan M-P. Contextual uncertainties, human mobility, and perceived food environment: the uncertain geographic context problem in food access research. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(9):1734–7.

Duncan DT, Piras G, Dunn EC, Johnson RM, Melly SJ, Molnar BE. The built environment and depressive symptoms among urban youth: a spatial regression study. Spatial Spatio-Temporal Epidemiol. 2013;5:11–25.

Black JL, Macinko J. The changing distribution and determinants of obesity in the neighborhoods of New York City, 2003–2007. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(7):765–75.

Stewart OT, Carlos HA, Lee C, Berke EM, Hurvitz PM, Li L, et al. Secondary GIS built environment data for health research: guidance for data development. J Transp Health. 2016;3(4):529–39.

Burgoine T, Harrison F. Comparing the accuracy of two secondary food environment data sources in the UK across socio-economic and urban/rural divides. Int J Health Geogr. 2013;12(1):2.

Chen X, Lin X. Big data deep learning: challenges and perspectives. IEEE Access. 2014;2:514–25.

Jin X, Wah BW, Cheng X, Wang Y. Significance and challenges of big data research. Big Data Res. 2015;2(2):59–64.

Coulton C. Defining neighborhoods for research and policy. Cityscape. 2012:231–6.

Duncan DT, Kawachi I, Subramanian S, Aldstadt J, Melly SJ, Williams DR. Examination of how neighborhood definition influences measurements of youths’ access to tobacco retailers: a methodological note on spatial misclassification. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;179(3):373–81.

Tatalovich Z, Wilson JP, Milam JE, Jerrett M, McConnell R. Competing definitions of contextual environments. Int J Health Geogr. 2006;5(1):55.

Acknowledgments

We are especially grateful to Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University (Janene Brown, Dustin Fry, Sharon Dei-Tumi), LeBow School of Business, Drexel University (Erik Dolson), and Columbia University (Brennan Rhodes Bratton) for their outstanding research assistance in auditing the ambiguous SIC codes. This work was enhanced by expert input by the Columbia University Built Environment Health Group (Tanya K. Kaufman, Nicolas Berger) for their work in categorizing the healthcare- and food-relevant locations in the New York-New Jersey-Pennsylvania metropolitan area. We are also grateful to the University of Alabama-Birmingham (Suzanne E. Judd) and Drexel University (Amy Auchincloss) for their input on the food categories; the New York Academy of Medicine (David S. Siscovick) and Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (Jennifer Tsui) for their input on the healthcare categories; University of Pittsburgh (Christina Mair) for her input on social and depression-related categories; and the investigators and staff of the “Communities Designed to Support Cardiovascular Health” team [National Institute of Aging (1R01AG049970, 3R01AG049970-04S1)] for their valuable contributions. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1R01AG049970, 3R01AG049970-04S1); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant R01HL131610); the Pennsylvania Department of Health (SAP #4100072543); the Urban Health Collaborative at Drexel University; and the generous gift from Dana and David Dornsife to the Drexel University Dornsife School of Public Health, whose funding made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR and GS conceived this project and obtained funding to execute it. JC, JQ, JH, KM, YZ, and FB helped classify, process, and analyze the dataset for this manuscript including statistical and geospatial elements. JH, KM, FB, and GS interpreted the data and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All the authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 81 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hirsch, J.A., Moore, K.A., Cahill, J. et al. Business Data Categorization and Refinement for Application in Longitudinal Neighborhood Health Research: a Methodology. J Urban Health 98, 271–284 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00482-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00482-2