Abstract

This paper provides evidence for the following novel insights: (1) People’s economic decisions depend on their psychological motives, which are shaped predictably by the social context. (2) In particular, the social context influences people’s other-regarding preferences, their beliefs and their perceptions. (3) The influence of the social context on psychological motives can be measured experimentally by priming two antagonistic motives—care and anger—in one player towards another by means of an observance or a violation of a fairness norm. Using a mediation approach, we find that the care motive leads to higher levels of cooperation which are driven by more optimistic beliefs, a different perception of the game as well as by a shift towards more pro-social preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper investigates how two psychological motives—care and anger—affect economic decisions in the context of a social setting characterized by strategic complementarities. A “social setting" features a joint activity of several people producing a distribution of payoffs. We focus on a cooperative setting in which one person’s contribution raises another person’s productivity (payoff per unit of contribution), i.e., a strategic complementarity. A psychological “motive" is a force that gives direction and energy to one’s behavior, thereby shaping the objective of the behavior.Footnote 1

Out of the variety of motives discussed in motivation psychology, we study the two antagonistic motives of care and anger. With the care motive, also referred to as compassion (Goetz et al., 2010) or prosocial altruism (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2010), individuals receive utility by increasing the wellbeing of others even at a personal cost (Goetz et al., 2010; Condon & Feldman Barrett, 2013; Batson & Shaw, 1991). Care-motivated individuals feel responsible for the wellbeing of others and therefore tend to create a cooperative environment. This tendency rests on the belief on the cooperativeness of others (Crocker & Canevello, 2012). With the anger motive, individuals are willing to sacrifice to harm others (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2010) or to make anti-social welfare decisions (Small & Lerner, 2008). Additionally, individuals motivated by anger have a desire of wanting and perceive others as competitors (Van Kleef et al., 2008).

Motives are closely associated with decision objectives and can be represented by a family of preferences. On this account, it is useful to associate economic decisions with motives, rather than emotions, which can be understood as affective states underlying, or associated with motives.Footnote 2

Motivation psychology argues that individuals are “multi-directed", i.e., they have access to multiple discrete motives. The phenomenon of multidirectedness makes context dependence central to preference formation since contexts serve to activate motives. In economic terms, individuals do not maximize a single utility function across contexts, but different contextual stimuli lead to different motives, which are associated with different utility functions (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2010; Bosworth et al., 2016).

Different motives can be associated with different decision objectives. With regard to economic decision-making, multi-directedness thus implies that different motives are associated with different preferences and the activation of a particular family of preferences is context dependent. Since motives are directly linked to specific goals (Chiew & Braver, 2011), they are a natural candidate to be translated into distinct preference functions.

In this context, this paper provides evidence for multi-directedness, indicating how different motives give rise to different economic decision objectives and how these motives are predictably shaped by the social context. We measure the influence of the social context experimentally by priming two antagonistic motives—care and anger—in one player towards another player by means of an observance or a violation of a fairness norm. We find that priming care generates prosocial other-regarding preferences, whereas priming anger pulls in the opposite direction. Furthermore, this paper shows that psychological motives not only shape decision objectives, but also perceptions and beliefs. Using a mediation approach, we find that the care motive leads to higher levels of cooperation which are driven by more optimistic beliefs, a different perception of the game as well as by a shift towards more pro-social preferences. In mainstream economic theory, preferences are depicted as reasonably stable through time and internally consistent, and furthermore these preferences are treated as independent of perceptions (generating one’s information set) and beliefs (concerning one’s context). By providing evidence that motives drive preferences, perceptions and beliefs in predictable ways, this paper breaks new ground.

We do so through an experiment on motive-driven decision-making in a social dilemma game. At the beginning of our experiment, one of these two motives is experimentally primed by an observance or a violation of a fairness norm. The primed motive then influences the beliefs, perceptions and preferences that shape the individual’s actions in a non-linear public goods game. The non-linear public goods game is based on the experimental design of Potters and Suetens (2009) and is characterized by strategic complementarity and a positive externality. Cooperation in this setting is particularly important because of these two properties, which are very common in practice. Examples of such settings are search and matching in labor markets (a worker searches for jobs to increase a firm’s profits, ceteris paribus, and increases the effectiveness of a firm’s search for workers), synergies in the workplace (a worker’s willingness to cooperate with a colleague increases the firm’s profit and promotes the colleague’s productivity due to willingness to cooperate with the worker), and trust under incomplete contracts (one party’s trust promotes the surplus of the trading partner and enhances the effectiveness of the trading partner’s trust).

The outcome of the social interaction, in turn, affects the individual motives. This feedback between motives and social interactions is particularly significant for an explanation of how social motives operate. In practice, naturally, social motives bring people into social interactions, which, in turn, affect their social motives (Bault et al., 2017).

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 relates our work to the existing literature. In Sect. 3, we outline the experimental methods; in Sect. 4 we formulate our hypotheses, which we test in Sect. 5; and in Sect. 6, we conclude with a discussion of our findings.

2 Relation to the literature

Care and anger are common social motives in the sense that they mediate social interactions and that are present in the economics literature. The motive care refers to altruism and prosociality including models of other-regarding preferences, positive reciprocity, guilt aversion and signaling of preferences (see Rotemberg (2014) for a comprehensive summary). The motive anger has been studied theoretically (Battigalli et al., 2019; Akerlof, 2016; Aina et al., 2020; Winter et al., 2016; Brams, 2011; Passarelli & Tabellini, 2017), in the context of pricing (Anderson & Simester, 2010; Rotemberg, 2005) and experimentally (Gneezy & Imas, 2014; Van Leeuwen et al., 2017; Persson, 2018; Castagnetti & Proto, 2020).

Though there is large body of empirical and experimental research documenting that individuals exhibit other-regarding preferences (Fehr & Schmidt, 1999; Fehr & Fischbacher, 2002; Charness & Rabin, 2002), there has been relatively little investigation of the systematic context-dependence of other-regarding preferences. An important aspect of social contexts are shared values or standards, so-called social norms. While norms offer guidance in social interactions and help to facilitate coordination (Bicchieri, 2016; Bicchieri & Dimant, 2019), norm violations can have lasting negative implications on future social interactions by eliciting negative emotional responses (Strang et al., 2016; Pillutla & Murnighan, 1996) and fostering self-interested behavior (Bicchieri et al., 2022).

In this paper, we show that other-regarding behavior can be systematically influenced by the observance or violation of a fairness norm. A theoretical background connecting motives to economic decision-making is outlined in Bosworth et al. (2016) as follows: (1) All behavior is motivated. (2) People have access to multiple discrete motives. (3) Each motive is associated with a distinct preference function. (4) Motives are activated by stimuli in a person’s internal or external environment. Based on this theoretical background, Bosworth et al. (2016) argue that motives and the likelihood of their activation based on individual traits are evolutionarily linked to the economic and social context. The economic and social context in Bosworth et al. (2016) is specified in terms of strategic complements and substitutes, the former promoting cooperation, and the latter inducing competition.

The behavioral economics literature acknowledges that contextual differences—particularly those based on framing (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981), priming (Cohn & Maréchal, 2016; Dimant, 2022; Drouvelis et al., 2015), perception (Dimant & Hyndman, 2019) and institutional norms (Peysakhovich & Rand, 2015; Engl et al., 2021)—can lead to systematically different behaviors. The literature on priming in behavioral economics focuses primarily on experiments in which behavior and judgment are influenced by the activation of mental concepts through situational cues. As such, it rests on empirical techniques in experimental psychology.Footnote 3 The prime commonly comes in the form of a stimulus that activates associated memories (Callen et al., 2014) or concepts (Cohn et al., 2015). The stimuli may be explicit in the form of words (Drouvelis et al., 2015) or the recollection of past experiences (Bogliacino et al., 2017) or implicit in the form of music (North et al., 1999), images (Vohs et al., 2006), unscrambling sentences (Bargh et al., 1996), temperature (Williams & Bargh, 2008), odor (Holland et al., 2005), and even subliminal stimuli (McKay et al., 2011). An underlying theory that offers a coherent explanation of these effects with regard to economic decision-making has thus far been absent. This paper contributes to filling this gap by providing a link among motivation psychology, primes and economic behavior.

Our research is also related to the following literature. Inline with Battigalli et al. (2019), we explore how an initial stimulus and the history of interaction between two individuals lead to the endogenous formation of preferences and beliefs under different motives. Similar to Cox et al. (2007), we observe reciprocal behavior, i.e., people treat others as they have been treated, which we interpret as an outcome of the interaction between the motives care and anger. Bartke et al. (2019) induce care and anger motives via autobiographical recall and study subsequent behavior in a one-shot linear public goods experiment. They show that individuals recalling memories associated with the care motive behave more pro-socially than individuals recalling memories associated with the anger motive. While this study analyzes a one-shot interaction without feedback between motives and social interactions, we study a repeated interaction with such feedback. Finally, Chierchia et al. (2017) investigate how motives of care and power, and motives of control and self-efficacy affect cooperation and punishment behavior. They find that individuals with care motives behave more cooperatively, while individuals with power motives are more willing to punish social norm violations. However, the effect of feedback from interpersonal cooperation and punishment on the motives is not studied. Moreover, because this study only recorded unconditional choices, it is unclear whether beliefs, preferences or both are changing. By eliciting conditional choices and thereby controlling for beliefs we show that motives indeed give rise to different objective functions.

3 Methods

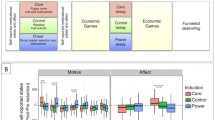

To test the outlined theoretical framework, we conducted a two stage experiment (see Fig. 1 for an overview). In each session, the participants were randomly divided into pairs, which stayed the same throughout the experiment. Every participant received the same instructions (see Appendix 2). In the first stage, we experimentally primed one of the two antagonistic motives care and anger in one player towards another by means of a dictator game with a restricted choice set. After a motive validation, participants entered the second stage in which they repeatedly interacted in a social dilemma game characterized by strategic complementarity and a positive externality in the same group. Since, we aim at testing whether the induced motives give rise to different behavior during the interaction and how beliefs, perceptions and preferences account for the observed differences in behavioral patterns, we repeatedly validated the motives and elicited unconditional choices, beliefs about the other player’s choices and conditional choices. Perceptions about the game environment were elicited in a subsequent questionnaire.

3.1 Motive prime

In the first stage, we aimed at priming the two antagonistic motives care and anger via a dictator game with a restricted choice set. To this end, one of the group members was randomly selected to be the dictator, and the other to be the receiver. In contrast to the classical version, here, the dictator cannot choose any distribution of the initial endowment but can only choose from a limited set of alternatives, as done, for example, by Bolton et al. (1998) or Schulz et al. (2014). This feature allows an experimenter to manipulate the frequency of certain outcomes. Specifically, we operationalize the emotional reaction to compliance and violation of a fairness norm, whereas perceived fairness about the distribution of the endowment is associated with the induction of the motive care (Singer et al., 2006) and perceived unfairness about the distribution is associated with the induction of the motive anger (Strang et al., 2016; Pillutla & Murnighan, 1996). Based on this approach, we construct two choice sets consisting of two options (Table 1). The dictator is endowed with 20 EUR and has to decide how to split this endowment between herself and the receiver according to the choice options. Option 1 determines the treatments in both choice sets. An equal split is associated with the care treatment and an unequal split, in which the dictator keeps 90% of the endowment is associated with the anger treatment. The choice sets were restricted to create a constant stimulus within one treatment. An equal split is typically perceived as fair, whereas keeping 90% of the endowment is perceived as unfair (McCall et al., 2014).

Option 2 is the same in both choice sets and includes an unfair split in which the dictator keeps only 10% of the endowment. Option 2 is therefore unlikely to be chosen by the dictator in both choice sets.

The dictator makes decisions for both choice sets. One decision is randomly reported to the receiver. The receivers are informed that there is a restricted choice set, but they do not know what the restricted choice set is. This is justified since we aim at inducing an emotional reaction to the distribution without any further procedural justifications of the dictators’ choice. The revealed decision determines whether the treatment is care or anger. This allows us to conduct both treatments in the same session and avoid any day-specific effects (Howarth & Hoffman, 1984). The dictator is only told that one of the two decisions is reported to the receiver to exclude a direct effect of the prime on the dictator.

3.2 Motive validation

During the experiment, we validated the activation and intensity of the motives at various points of both the receiver and the dictator. Specifically, we measured the motive after the dictator game to check whether our motive induction was successful and four times during the social dilemma game in order to observe the evolution of the motives throughout the repeated interaction. Given that only the receiver was treated initially, we expect treatment differences after the motive induction for the receiver only. However, throughout the interaction we expect a motive spill over to the dictator.

The motive validation was done via self-reported ratings of motivational states based on words associated with the motives care and anger. For the ratings, we used seven-point Likert scales with words taken from the word atlas assembled by Chierchia et al. (2021), who asked people to assign words to different motives. The words used in this experiment are outraged (“How outraged are you about the decision of participant B?”) and upset (“How upset are you about the decision of participant B?”) for the anger motiveFootnote 4, and likable (“How likable do you find participant B?”) and compassionate (“How compassionate are you with participant B?”) for the care motive. The ratings are formulated directly towards the other player. We average the two ratings for each motive to derive a care score and an anger score.

To avoid collinearity in our subsequent analyses, we construct a motive score, which is the difference between the care and anger scores as follows:

Taking the difference is theoretically justified because the two motives are antagonistic. Additionally, in our data, the care and anger scores are negatively correlated (\(r(214)=-0.51, ~p<.001\)). Hence, a positive motive score indicates that the care motive dominates, while a negative score indicates that the anger motive dominates.

3.3 Social dilemma game

Bosworth et al. (2016) suggest that the care motive has a comparative advantage in a social setting characterized by strategic complements. Such a context should therefore offer care-motivated individuals the opportunity to fully exploit the benefits of this motive. To test this suggestion, each group plays a repeated social dilemma game in the second stage of the experiment. The social dilemma game is based on the experimental design of Potters and Suetens (2009) with a payoff function that has the following form:

with \(x_{i}, x_{j}\ge 0\) denoting the contribution of player i and j respectively and the parameter \(b, c, d, f, e>0\) are the calibration parameters of the payoff function. The game has a positive externality (\(\partial \pi _{i}(x_i, x_j)/\partial x_{j}>0\)), and the choices are strategic complements (\(\partial ^{2}\pi _{i}(x_i, x_j)/\partial x_{i}\partial x_{j}>0\)). The characteristic choices and payoffs of their calibration of the parameters (\(a=-28\), \(b=5.474\), \(c=0.01\), \(d=0.278\), \(e=0.0055\) and \(f=0.165\)) are summarized in Table 2, where \(x^\textrm{Nash}\) is the Nash equilibrium and \(\pi ^\textrm{Nash}\) the corresponding payoff, \(x^\textrm{JPM}\) is the joint payoff maximizing choice and \(\pi ^\textrm{JPM}\) the corresponding payoff, \(\pi ^\textrm{defect}\) is the payoff maximizing best response to full cooperation (see Potters and Suetens (2009) for details of the parametrization).

Cooperation in this setting is particularly important as outlined in the introduction. To determine whether individuals with an induced care motive behave more cooperatively and whether this behavior can be explained by a shift in preferences, beliefs or perception, we elicit both unconditional and conditional choices based on the strategy method (Fischbacher et al., 2001)Footnote 5 as well as beliefs.

Specifically, the participants played the social dilemma in the same group for 16 rounds. In each round, the participants were asked to choose a number between 0.0 and 28.0 and to state a belief about the choice of the other player in their group. They were equipped with a payoff table (Appendix 2: Fig. 8) and a calculator, which was implemented as a slider. On this slider, they could enter a hypothetical choice and the belief about the choice of their counterpart. Based on these hypothetical numbers, the participants received information about their own payoff and the payoff of their counterpart. Beliefs were incentivized with 5 points if the stated belief was within ± 1 range of the counterpart’s actual choice. After each round the participant received a feedback on the choices, payoffs and cumulative payoff for themselves and their counterpart.

Additionally, in rounds 1, 2, 6, 11 and 15, the motives were validated as described above and the participants were asked to state their conditional choices based on the strategy method. This included fifteen possible hypothetical choices of the other player (values from 0 to 28 in steps of two).

The actual payoff in these rounds was determined randomly from the unconditional or the conditional choices. If the conditional choices were selected, the payoff relevant choice was implemented as the conditional choice corresponding to the unconditional choice of the other player. If the number was between the pre-defined hypothetical choices of the counterpart, the conditional choice was linearly approximated between the upper and lower bound as explained to the participants beforehand.

The first round was a test round and, therefore, was excluded in the final payoff calculation. The payoffs were denoted by points (50 points = 1 EUR) and summed over all rounds.

At the end of the experiment, participants were asked to state their perception of the nature of the game as either cooperative or competitive.

The non-linearity of the social dilemma game allows us to estimate a preference shift attributed to the induced motives care and anger. In particular, controlling for beliefs, the choices from the strategy method enabled us to estimate the individual preference signature of each participant based on the theoretical best-response functions.

To explore the preference signature resulting from the two induced motives of interest and following Bosworth et al. (2016), we assume that the utility function of an individual in a two-player interaction is represented by

where \(\pi _i\) and \(\pi _j\) are the respective payoffs from a social interaction of players i and j. Player i’s utility is a combination of the two payoffs, and \(\kappa _{i}\) measures their relative weights. If \(\kappa _{i} >0\), an increase in the payoff of the other player in the game increases the utility of the focal player. This feature is typically associated with the motive care (Bosworth et al., 2016). If \(\kappa _{i} <0\), the focal player receives disutility from the payoff of the other player in the game (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2010). This feature is typically associated with the motive anger. If \(\kappa _{i} =0\), the payoff of the other player does not affect the utility of the focal player (Bosworth et al., 2016). This corresponds to the neoclassical motive of selfish wanting. In the following, we refer to \(\kappa _{i}\) as the preference signature.

Based on the payoff function, we derive the following theoretical best-response function for each value of the preference signature \(\kappa _{i}\):

The best response is increasing in \(\kappa _{i}\). Hence, individuals with a higher \(\kappa _{i}\) value choose unconditionally higher numbers in the social dilemma game as shown in Fig. 2. The best-response function increases with \(x_{j}\), and higher values of \(\kappa _{i}\) are associated with higher intercepts and steeper slopes. This is due to the properties of the payoff function, since the own contribution has a positive effect on the wellbeing of the other player.

3.4 Experimental procedure

The experiment was conducted at the economics laboratory of the Kiel University in October 2017. We recruited 230 participants from the subject pool, which consists of Kiel University students with various scientific backgrounds.Footnote 6 Data was collected in 17 sessions with 12–20 participants per session. The organization and administration were performed using the hroot platform (Bock et al., 2014), and the experiment was set up using the experimental software oTree (Chen et al., 2016). For technical issues, we had to exclude two observations (one couple) because their computers lost connections to the server and twelve more observations (6 couples) because the dictator’s choices did not reflect the randomly assigned motive treatment, that is, the dictator in the anger treatment opted to keep 2 EUR and send 18 EUR. The remaining 216 participants (96 were women) were distributed across the two treatments, with 102 in the anger treatment and 114 in the care treatment. This corresponds to 108 independent observations. Please note that three dictators in the care treatment decided to send 18 EUR and keep 2 EUR, while all other dictators decided for an equal split. Because this signal is in line with the assigned motive treatment, the observations were included in the analysis.

For the individual payment, it was randomly determined whether the dictator or the social dilemma game was paid out. The sessions lasted between 50 and 75 min, and the average payment per participant was 16.33 EUR.

3.5 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the computing environment R (R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2016); RStudio version 1.3.1056 (RStudio Team, 2015)). The best-response functions were fitted with the function mle2 in the bbmle package (R Core Team, 2020). Mediation analysis was performed with the mediation package (Tingley et al., 2014).

Our dependent variables are as follows:

-

Unconditional choices as elicited in the social dilemma game.

-

Conditional choices as elicited via the strategy method.

-

Beliefs about one’s counterpart’s behavior.

-

Perception about the nature of the game.

To study the impact of the motives on those dependent variables, we perform a mediation analysis. The goal of the mediation analysis generally is to decompose the treatment effect into a direct effect of the treatment on the outcome variable and an indirect effect that works through one or more intermediate variables which are manipulated by the treatment. These intermediated variables are called mediators. In economics, mediation analyses have been applied in various settings, such as to evaluate the impact of labor market programs on employment and earnings (Huber et al., 2018), the effect of financial education on financial behavior (Carpena & Zia, 2020), the mechanism of cognitive and non-cognitive skills and the effect of personality traits on health (Heckman et al., 2013; Keele et al., 2015; Conti et al., 2016), and the mediating effect of education between growing up poor and economic outcomes in adulthood (Bellani & Bia, 2019).

We first present the results of the traditional mediation approach as developed by Baron and Kenny (1986) and then complement the results with a causal mediation approach as developed by Imai et al. (2010). The traditional approach rests on the following four steps:

-

Step 1:

We show that the treatment (care vs. anger prime) significantly impacts the dependent variables in the social-dilemma game. This step establishes that there is an effect that may be mediated.

-

Step 2:

We show that the treatment significantly changes the motive scores. This step establishes that the treatment has an effect on the potential mediator.

-

Step 3:

We show that the motive scores significantly affect the dependent variables. This, however, is not sufficient to establish mediation because both the outcome variable and the potential mediator are impacted by the treatment.

-

Step 4:

We perform a multiple regression with the treatment variable and the motive scores, i.e., we control for the direct effect of the treatment on the dependent variables. Mediation is supported if the motive scores continue to have a significant impact on the dependent variables after the treatment is controlled for. If the treatment variable is no longer significant, this finding is called a full mediation, otherwise the finding is called a partial mediation.

To confirm the statistical significance of the indirect effect via the mediator, we complement these results with insights from causal mediation techniques (Imai et al., 2010). The causal mediation approach is based on a counterfactual framework. Let \(Y_{i}\) be the dependent variables in the social dilemma game (unconditional choices, beliefs, conditional choices), \(T_{i}\) the treatment status (\(care=1\) and \(anger=0\)) and \(M_{i}\) the value of the mediator variable (motive score) for individual i. The observed outcome, \(Y_{i}\), equals then \(Y_{i}(T_{i}, M_{i}(T_{i}))\), where \(M_{i}(T_{i})\) is the observed value of the motive score in the given treatment. The total unit treatment effect is then given by \(\tau _{i} = Y_{i}(1,M_{i}(1))-Y_{i}(0,M_{i}(0))\). This effect can be decomposed into a) the causal mediation effect, also referred to as the indirect effect,

for the treatment status \(t=0,1\) and b) the direct effect which accounts for all other causal mechanisms

for the treatment status \(t=0,1\) (Pearl, 2014; Robins & Greenland, 1992). These two effects sum up to the total effect

The average causal mediation effects (ACME) \(\bar{\delta _{i}}\) and the average direct effects (ADE) \(\bar{\zeta _{i}}\) represent the corresponding population averages. The identification of ACME and ADE rests on the assumption of Sequential Ignorability proposed by Imai et al. (2010). Sequential Ignorability consists of the following three conditions:

where \(X_{i}\) is a vector of the observed pre-treatment confounders for individual i. The first condition (i) of Sequential Ignorability implies that the treatment assignment is assumed to be ignorable, i.e., statistically independent of potential outcomes and potential mediators. This is ensured by design in our study, since treatments are assigned randomly. Condition (ii) implies that the motive score is ignorable given the observed treatment and pre-treatment confounders. This condition is quite strong and will be violated if there are (measured or unmeasured) post-treatment confounders or unmeasured pre-treatment confounders that influence both the motive score and the outcome variable. We address this issue in more detail in Sect. 5.8. Condition (iii) is a support condition that allows the estimation of treatment effects. Imai et al. (2010) show that under this set of assumptions, it becomes possible to estimate the ACME and ADE with the following two equations.

The ACME is then given by \({\hat{\beta }}_{1} \cdot {\hat{\gamma }}_{2}\) and the ADE by \({\hat{\beta }}_{2}\). The standard errors and confidence intervals can be derived from a quasi-Bayesian Monte Carlo approximation as implemented by Tingley et al. (2014).

4 Hypotheses

If the motive induction is successful, we will expect a higher motive score in the care than in the anger treatment. Since the dictators make both treatment decisions and are not informed about which of their choices is revealed, we should not observe an initial treatment difference in their motive scores. In the second stage, participants interact repeatedly. Throughout this interaction, we expect the motives to change due to experience and outcomes of these interactions. However, we predict that the initially primed motive of the receiver is carried over to the social dilemma game and thereby significantly influences the trajectories of these interactions. As a result, we hypothesize that receivers in the care treatment act more cooperatively compared to receivers in the anger treatment. Although the dictators are not treated, we expect that the receivers’ motives spill over to the dictators due to the experienced level of cooperation.

Our hypotheses for the main dependent variables (unconditional and conditional choices, beliefs and perceptions) are derived from the characteristics of the motives care and anger. Individuals motivated by care feel responsible for the wellbeing of others (Goetz et al., 2010; Condon & Feldman Barrett, 2013; Batson & Shaw, 1991), whereas individuals motivated by anger are willing to sacrifice own wellbeing to harm others (Heckhausen & Heckhausen, 2010; Small & Lerner, 2008). Since the social dilemma game is characterized by strategic complementarity and a positive externality, higher choices have a positive effect on the counterpart. Consequently, we expect that receivers in the care treatment have higher unconditional choices than in the anger treatment. Furthermore, it has been shown that individuals motivated by care tend to create a cooperative environment which rests on the belief of cooperativeness of others (Crocker & Canevello, 2012), while individuals motivated by anger perceive others as competitors (Van Kleef et al., 2008). Hence, receivers in the care treatment should have higher beliefs about the choices of their counterparts and appraise the social dilemma game as cooperative rather than competitive. Finally, individuals motivated by care should have more prosocial preferences than individuals motivated by anger. In order to test this prediction, we measure the preference shift based on the strategy method by fitting the previously derived best-response functions and estimating the preference signature \(\kappa\). Consequently, we expect higher conditional choices for receivers in the care treatment than in the anger treatment which translate into a higher values of \(\kappa\).

5 Results

5.1 Motive induction

First, we determine whether the dictator game with a restricted choice set indeed reliably primed the predicted motives of care and anger. In Fig. 3, the average motive scores for the dictator and the receiver by experimental condition and round number are presented. For the receiver in round one, a t-test reveals that the motive score is significantly higher in the care treatment (\(M=4.65\), \({{SE}}=0.20\)) than in the anger treatment (\(M=-2.61\), \({\textit {SE}}=0.35;~t(106)=18.63,~p <.001\)). This finding suggests that the manipulation was successful. Using ordinary least-squares regression with cluster-robust standard errors at the individual level and excluding the first round, we found that the motive scores were persistently higher in the care treatment than they were in the anger treatment (\(\beta = 2.08,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.45,~p<.001\), see Table 3). Where it is appropriate, we include the reciprocal of the round number (1/round as Round_rec) as an explanatory variable as suggested by Moffatt (2015) in our models. This variable is thought to capture learning effects or other temporal dynamics that could potentially arise as participants become more familiar with the task or for other reasons move to another long-term equilibrium. A positive coefficient for this variable would indicate a decrease in the dependent variable during the experiment. In our analysis, we observe a general decrease in the motive score for the receiver (\(\beta = 1.02,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.50,~p=.046\), see Table 3).

As expected, the motive score in the first round is not significantly different for the dictator, who was not informed of which decision was revealed to the receiver (care: \(M=2.45\), \({\textit {SE}}=0.23\); anger: \(M=1.97\), \({\textit {SE}}=0.22\); \(t(106)=1.49,~p =.138\)). During the experiment, however, we observe that the motive score was significantly higher in the care treatment than in the anger treatment when the first round is excluded (\(\beta = 1.07,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.44,~p=.017\), see Table 3). This result suggests that there was a motivational spillover effect from the receiver to the dictator during their interaction.

To further investigate this effect, in Table 4, we describe how the motive score of the receiver in round t affects the motive score of the dictator in round \(t+1\). An ordinary least-squares regression with cluster-robust standard errors at the individual level confirms a positive spillover effect (\(\beta = 0.19,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.07,~p =.009\), see Table 4). The channel through which this effect operates seems to be the choices of the receiver in the corresponding rounds, as shown in Table 4 (\(\beta = 0.12,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.03,~p <.001\), see Table 4).

In a nutshell, our analysis shows that the motive priming was successful in eliciting the targeted motives. Because we are interested in how the primed motives affect choices, beliefs and preferences, the subsequent analysis is based on mediation analyses.

5.2 Unconditional choices

Our theory predicts that with the care motive, individuals internalize the positive externalities of their actions to a greater degree than they do with the anger motive. Therefore, the level of cooperation measured by the average number chosen should be greater. Figure 4 shows the average choices for the receiver and the dictator throughout the experiment separately by treatment. A visual inspection of the data suggests that the average unconditional choices and, therefore, the levels of cooperation for the receiver are higher in the care treatment than in the anger treatment throughout the experiment. In Table 5, this visual impression is statistically confirmed by an ordinary least-squares regression with cluster-robust standard errors at the individual level (\(\beta = 1.63,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.75,~p= .032\)). We also confirm statistically that the motive scores significantly affect the unconditional choices (\(\beta = 0.32,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.08,~p <.001\)). When running a multiple regression including both the treatment variable and the motive scores, we find that the motive scores continue to significantly influence the unconditional choices (\(\beta =0.28,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.11,~p =.017\)). The treatment dummy is no longer significant (\(\beta =0.51,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.78,~p =.510\)), which suggests a full mediation of its impact on choices via the motive scores. The significance of the indirect effect is confirmed using the causal mediation approach (\({\textit {ACME}} = 0.87,~95\%~{\textit {CI}} = [0.17, 1.65],~p = .014\), see Table 6). In all models, we observe a significant positive temporal trend, which suggests that the unconditional choices decrease throughout the experiment (\(p<.01\)).

For the dictator, we do not observe significant differences in unconditional choices by treatment (\(\beta =1.08,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.78,~p =.170\), see Table 7). For completeness, we report all statistical models necessary to confirm mediation, but given the previous finding, mediation appears unlikely.

Unconditional choices inform us about the level of cooperation with each primed motive. However, it is unclear whether beliefs, preferences or both drive the difference in behavior. To disentangle the effects of beliefs and preferences on observed behavior, we analyze them separately.

5.3 Beliefs

In the next step, we analyze how beliefs about the behavior of one’s counterpart change by treatment and motive. Since we are in a context characterized by strategic complements, individuals have incentives to cooperate more when they believe that their counterparts select larger numbers. Beliefs were incentivized and elicited at the same time when the unconditional choices were recorded. Figure 5 shows the time course of the elicited beliefs by treatment. The figure reveals that receivers in the care treatment believe that their counterparts choose higher numbers as compared to individuals in the anger treatment.

This is statistically confirmed in Table 8 (\(\beta =1.69,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.78,~p =.032\)). Again, this relation is mediated by changes in motive scores (\(\beta = 0.24,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.12,~p =.049\)). The causal mediation analysis in Table 9 supports the statistical significance of the indirect effect (\({\textit {ACME}} = 0.76,~95\%~{\textit {CI}} = [0.01, 1.58],~p = .045\)).

For the dictator, we do not observe a significant effect of the treatment on beliefs (\(\beta = 0.88,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.78,~p =.253\), Table 10) and mediation, therefore, appears unlikely.

Please note that we observe a strong correlation between beliefs and unconditional choices (\(r(214)=0.92, ~p<.001\)). This correlation holds for both treatments, although the correlation is stronger in the care treatment than in the anger treatment (care: \(r(112)=0.96, ~p<.001\), anger: (\(r(100)=0.87 ~p<.001\)). Given the nature of the experimental task which is characterized by strategic complements, the positive correlation between beliefs and unconditional choices is not surprising. As a consequence of the strong correlation, however, we refrain from estimating models including both beliefs and unconditional choices to avoid problems of multicollinearity.

5.4 Perception

At the end of experiment, we asked the participants whether they perceived the nature of the experimental game as (a) cooperative or (b) competitive. Evidence suggests that a cooperative priming (Drouvelis et al., 2015) and a cooperative perception of a situation (Bartke et al., 2019) increase pro-social behavior. Acknowledging that perceptions matter for economic behavior (Weber, 2004) and that anger (care) is associated with competition (cooperation) (Van Kleef et al., 2008; Chierchia et al., 2017) , we hypothesize that individuals motivated by the care motive tend to perceive the experimental game as cooperative, whereas individuals motivated by anger should tend to perceive the game as competitive. In line with these hypotheses, we find that a significantly larger fraction of receivers describe the game environment as cooperative in the care treatment as compared to the anger treatment (\({\chi }^2=8.01,~p=.005\)). For the dictators, we do not observe such a tendency (\({\chi }^2=1.05,~p=.305\)).

5.5 Conditional choices

Finally, we look at conditional choices. By controlling for beliefs, we aim to determine whether the different motives are indeed linked to different preference signatures, i.e., different objective functions. In Fig. 6, we show the average conditional choices by treatment (care vs. anger) and for the receiver and the dictator separately. First, we observe that the conditional choices increase with the counterpart’s choice. This finding is not surprising given the nature of the game, which is characterized by strategic complements. Therefore, individuals have stronger incentives to choose higher numbers if their counterparts do so. This effect is significant for both players, as shown in Table 11 and Table 13 (receiver: \(\beta = 0.45,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.02,~p <.001\); dictator: \(\beta = 0.47,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.02,~p <.001\)). The receiver’s conditional contributions are significantly higher in the care treatment than in the anger treatment (\(\beta =0.72,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.25,~p =.004\)), and this effect is fully mediated by motive scores (\(\beta =0.11,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.03,~p<.001\)). The significance of the indirect effect is confirmed using the causal mediation approach (\({\textit {ACME}} = 0.36,~95\%~{\textit {CI}} = [0.17,~0.58],~p <.001\), see Table 12).

For the dictator, there is no significant treatment difference in conditional contributions (\(\beta =0.31,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.28,~p =.270\), see Table 13) making mediation unlikely.

As the final step in our analysis, we estimate the preference signatures \(\kappa\) resulting from the induced motives via the conditional contributions. We apply a Maximum Likelihood Estimation technique under the assumption that the residuals are normally distributed with zero mean. In a nutshell, our procedure aims at finding the \(\kappa\)-value that provides the best fit of the individual best-response function given the observed data. We base this analysis on the individual data from all five measurement points where the conditional choices we elicited to obtain stable estimates.

The value of \(\kappa\) indicates the degree to which the individuals internalize the well-being of their counterpart. Higher values of \(\kappa\) are associated with more pro-social objectives. The best-response functions based on the estimated values of \(\kappa\) are shown in Fig. 6. In Table 14, we observe that receivers have significantly higher values of \(\kappa\) in the care treatment than in the anger treatment (\(\beta = 0.20,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.07,~p =.027\)) with a full mediation via the motive scores (\(\beta = 0.04,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.02,~p =.017\)). Again, the significance of the indirect effect is confirmed by the causal mediation analysis (\({\textit {ACME}} = 0.12,~95\%~{\textit {CI}} = [0.02,~0.52],~p =.012\), see Table 12)

For the dictator in Table 16, we do not observe significant differences in the value of \(\kappa\) between the treatments (\(\beta = 0.14,~ {\textit {SE}}=0.10,~p =.171\)) making mediation unlikely.

5.6 Quantifying the priming effect

In this section, we quantify the effect of the prime on the preference signature \(\kappa\). For this purpose, we replace the treatment dummy (Anger = 0; Care = 1) with a continuous variable indicating the percentage shared by the dictator in the initial dictator game (Anger = 0.1; Care = 0.5). We then assume a linear relationship between different endowment splits (0–1) and thereby can obtain predictions for splits that were not included in our treatment variation.

In Fig. 7, we find that a selfish dictator who is not sharing any endowment with the receiver results in a predicted \(\kappa\)-value of the receiver which is close to zero. This suggests that as a result of an unequal split at the beginning of the experiment, receivers are not receiving utility by making their partners better off in the subsequent social dilemma game; or in terms of motivation psychology, they are not caring about their partners. On the other side of the spectrum, a full share of the initial endowment, results in receivers that give equal weight to their partners’ and their own payoffs (\(\kappa\)= 0.5), and thereby jointly maximize the outcome. Please note, however, that this prediction relies on the assumption about a linear relationship between the \(\kappa\)-values and the shared endowment which needs to be verified in future studies.

5.7 Earned points in the social dilemma game

Please note that individuals in the care treatment earned more points (\(M=522.11\), \({\textit {SE}}=10.28\)) in the social dilemma game than individuals in the anger treatment (\(M=479.02\), \({\textit {SE}}= 16.04;\, t(214)= 2.31,~p =.022\)). However, it was mainly the dictators profiting from the care motive induction (dictator-care: \(M=525.03\), \({\textit {SE}}=14.20\) vs. dictator-anger: \(M=449.57\), \({\textit {SE}}=27.05\); receiver-care: \(M=519.20\), \({\textit {SE}}=14.97\) vs. receiver-anger: \(M=508.48\), \({\textit {SE}}=16.54\)).

5.8 Robustness

In this section, we discuss the robustness of our results in the light of the assumption of Sequential Ignorability. Since Sequential Ignorability is a strong assumption it is necessary to understand how our results change due a violation of this assumption. The crucial part of the assumption is condition (ii) which implies that there are no (measured or unmeasured) post-treatment confounders or unmeasured pre-treatment confounders that effect both the mediator and the outcome. We employ the sensitivity analysis proposed by Imai et al. (2010) to evaluate the effect of a violation of this condition on our results. This sensitivity analysis is based on the correlation between the error terms of the Eqs. 8 and 9 (\(\rho =corr(\epsilon _{1i},\epsilon _{2i})\)). A higher correlation indicates a larger bias of the ACME. The idea is to relax the assumption of \(\rho =0\) and find the value of \(\rho\) at which the ACME is zero. For this end, the mediation analysis is calculated with different values of \(\rho\). A high value of \(\rho\) at which the ACME is zero indicates that the estimate are rather robust to a violation of Sequential Ignorability, while small values of \(\rho\) indicate a high sensitivity to a violation.

It appears that all four variables are sensitive to a violation of Sequential Ignorability (\(\rho _{\text {unconditional}}=0.14\), \(\rho _{\text {belief}}=0.12\), \(\rho _{\text {conditional}}=0.1\) and \(\rho _{\text {kappa}}=0.21\)). Generally speaking, the results for the preference signature \(\kappa\) are less sensitive than the results for the other variables. One critical point with respect to potential pre-treatment confounders might be that certain personality types could react more or less to the prime than other personality types. For example, an individual with a pro-social trait may react more to the care prime than an individual with a selfish trait. Therefore, the results of the sensitivity analyses need to be taken into account when interpreting the ACME results.

6 Discussion

In this paper, we show that motives can be experimentally primed by means of an observance or a violation of a fairness norm and that the primed motives give rise to different behavior in a social dilemma game. The behavior that we observe in our social dilemma game is driven by different beliefs, perceptions as well as different preferences due to the social norm violation. More specifically, we find that individuals with care motives are more pro-social than individuals with anger motives because they internalize the externalities of their actions to a higher degree. Overall, inducing a care motive appears to be one way to achieve more socially desirable outcomes in social dilemmas where individual actions have positive externalities. In sum, we show that other-regarding behavior can be malleable and that motivation psychology can help to explain why.

We acknowledge that other economic models of social behavior such as the belief-dependent reciprocity models of Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger (2004) and Falk and Fischbacher (2006) offer explanations for the behavior observed in our experiment: The dictator in the care condition treats the receiver kindly in the first stage of the experiment and—as a response—the receiver reciprocates in the subsequent interaction. We believe, however, that motivation psychology offers an explanation of why we observe this kind of correlation in behavior. We utilize the framework of motivation psychology and show that the relations between the initial prime and the subsequent social interaction are mediated by changes in motive scores. Moreover, motivation psychology offers tools to make the initial prime quantifiable. Using motives scores, we are able to quantify the initial priming effect and predict how other endowment splits may impact the subsequent game.

Some of our findings need further elaboration: We find that the motive score for the receiver in the anger treatment is negative after motive induction. This result suggests that the anger motive indeed is activated at that point in time. During the course of the experiment, however, the motive score increases and becomes positive, which suggests that the care motive is activated (although significantly less strongly than it is after the care motive has been primed). This finding is actually in line with the theoretical predictions outlined by Bosworth et al. (2016). Here, a social context characterized by strategic complements favors and activates the care motive. Therefore, the social interaction within this context potentially overrides the initial anger motive. This effect also plausibly explains why the average value of \(\kappa\) for receivers in the anger treatment is not negative (but is close to zero) as our hypothesis suggests it should be with an anger motive. For receivers in the care treatment, we observe that \(\kappa\), on average, is 0.23. This finding is in line with our theoretical prediction for the preference signature underlying the care motive. It suggests that while those individuals take the wellbeing of their counterparts into account, they still put more weight on themselves. For the dictators, all the effects of the treatments, on average, go in the same direction as for the receivers, but they do not reach the significance threshold in all cases. It appears, however, plausible that the effects for the dictators are less pronounced because they are not exposed to the initial strong signal through the dictator game.

Any form of deception should be avoided in experimental economics (Davis & Holt, 1993) and it is debated whether omitting relevant information is deception or not; so far no consensus has been reached (Krawczyk, 2013). In our experiment, we withheld information about the exact choice set of the dictator. It was necessary to omit this information, because otherwise we most likely would not have induced the motives of interest. We would like to highlight, however, that the receivers were informed that the dictators would choose from a pre-defined, yet unknown choice set. In that sense, participants held all relevant procedural information and knew the limits of their knowledge.

There are several important differences between our study and the existing literature on the role of motives in economic decision making, such as Bartke et al. (2019) and Chierchia et al. (2017). First, our motive induction method does not rely on any motivational carryover from an unrelated situation to the situation of interest. Our method, in contrast, induces a motive that is directed towards the person the player interacts with later. Second, we study a repeated interaction, whereas previous studies focused on one-shot situations. The repeated interaction allows us to study the dynamics of motives and in particular, how motives change through social interaction and how they affect the motive of one’s counterpart. Third, by controlling for beliefs, we show that motives give rise to different preference signatures.Footnote 7

Several limitations of our study need to be mentioned. First, our motive validation, which is based on self-reported measures, relies on the assumption that participants are able to be introspective. Without this ability, it would not be possible for them to report their current motivational state. Within the literature, the extent to which individuals have this ability has been debated (Zajonc, 1980). Moreover, it is always possible that the participants do not answer truthfully, which also challenges the validity of the self-reported measures. Due to this criticism, it is desirable to introduce new techniques for motive validation. One potential way to do this might be physiological reactions, such as skin conductance or heart rate, because empirical evidence suggests that motives have distinct neurobiological footprints. The care motive, for example, is characterized by a decrease in physiological arousal such as lower skin conductance or inhibition of heart rate (Eisenberg et al., 1988, 1991). The anger motive, in contrast, is associated with heightened physiological arousal, such as higher skin conductance or accelerated heart rate (Levenson et al., 1990; Herrero et al., 2010).

A second limitation of our experimental design might be a wealth effect due to the use of a dictator game with a restricted choice set. It has been shown that social preferences can be affected by such a wealth effect (Chowdhury & Jeon, 2014). In our experimental design, however, we effectively mitigate this effect as only one of the two games is paid out.

Third, it is important to think carefully about how our laboratory results are related to situations that people commonly encounter in practice. In particular, the question of how motives can be induced in the real world appears pressing. There seems to be evidence that motives can be induced via narratives (Akerlof & Snower, 2016), compassion training (McCall et al., 2014; Condon et al., 2013) and supportive social contexts (Crocker & Canevello, 2015).

Notes

A survey is provided in Bargh and Chartrand (2000).

Since the receiver took no decision in the dictator game, the validation question for the dictator was generalized in the first round for the words outraged (“How outraged do you feel?”) and upset ("How upset do you feel?”).

In this method, participants are asked to indicate an action for a range of possible specified actions of their counterpart. The aim is to control for differences in beliefs about one’s counterpart’s actions.

Our sample: STEM: 67, Humanities: 57, Law: 17, Medical Science: 9, Economics: 49, Psychology: 6, Social Science: 10, no information provided: 1.

Chierchia et al. (2017) did not control for beliefs, and therefore, it appears unclear whether beliefs are changing or indeed preferences. Bartke et al. (2019) provide a type analysis based on conditional contributions and observe more pro-social types in the care treatment than in the anger treatment. Their type analysis is in line with our observations.

References

Aina, C., Battigalli, P., & Gamba, A. (2020). Frustration and anger in the ultimatum game: An experiment. Games and Economic Behavior, 122, 150–167.

Akerlof, G. A., & Snower, D. J. (2016). Bread and bullets. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 126, 58–71.

Akerlof, R. (2016). Anger and enforcement. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 126, 110–124.

Anderson, E. T., & Simester, D. I. (2010). Price stickiness and customer antagonism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 729–765.

Atkinson, J. W. (1964). An introduction to motivation. Van Nostrand.

Bargh, J., & Chartrand, T. (2014). Studying the mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In H. Reis & C. Judd (Eds.), Research methods for the social sciences (pp. 253–285). Cambridge University Press.

Bargh, J. A., Chen, M., & Burrows, L. (1996). Automaticity of social behavior: Direct effects of trait construct and stereotype activation on action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 230–244.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bartke, S., Bosworth, S. J., Snower, D. J., & Chierchia, G. (2019). Motives and comprehension in a public goods game with induced emotions. Theory and Decision, 86(2), 205–238.

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2(2), 107–122.

Battigalli, P., Dufwenberg, M., & Smith, A. (2019). Frustration, aggression, and anger in leader-follower games. Games and Economic Behavior, 117, 15–39.

Bault, N., Fahrenfort, J. J., Pelloux, B., Ridderinkhof, K. R., & van Winden, F. (2017). An affective social tie mechanism: Theory, evidence, and implications. Journal of Economic Psychology, 61, 152–175.

Bellani, L., & Bia, M. (2019). The long-run effect of childhood poverty and the mediating role of education. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 182(1), 37–68.

Bicchieri, C. (2016). Norms in the wild: How to diagnose, measure, and change social norms. Oxford University Press.

Bicchieri, C., & Dimant, E. (2022). Nudging with care: The risks and benefits of social information. Public Choice, 191(3), 443–464.

Bicchieri, C., Dimant, E., Gächter, S., & Nosenzo, D. (2022). Social proximity and the erosion of norm compliance. Games and Economic Behavior, 132, 59–72.

Bock, O., Baetge, I., & Nicklisch, A. (2014). hroot: Hamburg registration and organization online tool. European Economic Review, 71, 117–120.

Bogliacino, F., Grimalda, G., Ortoleva, P., & Ring, P. (2017). Exposure to and recall of violence reduce short-term memory and cognitive control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(32), 8505–8510.

Bolton, G. E., Katok, E., & Zwick, R. (1998). Dictator game giving: Rules of fairness versus acts of kindness. International Journal of Game Theory, 27(2), 269–299.

Bosworth, S. J., Singer, T., & Snower, D. J. (2016). Cooperation, motivation and social balance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 126, 72–94.

Brams, S. J. (2011). Game theory and the humanities: Bridging two worlds. MIT Press.

Callen, M., Isaqzadeh, M., Long, J. D., & Sprenger, C. (2014). Violence and risk preference: Experimental evidence from Afghanistan. American Economic Review, 104(1), 123–148.

Carpena, F., & Zia, B. (2020). The causal mechanism of financial education: Evidence from mediation analysis. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 177, 143–184.

Castagnetti, A., & Proto, E. (2020). Anger and Strategic Behavior: A Level-k Analysis. Working Paper.

Charness, G., & Rabin, M. (2002). Understanding social preferences with simple tests. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(3), 817–869.

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 88–97.

Chierchia, G., Lesemann, F. P., Snower, D., Vogel, M., & Singer, T. (2017). Caring cooperators and powerful punishers: Differential effects of induced care and power motivation on different types of economic decision making. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 11068.

Chierchia, G., Przyrembel, M., Lesemann, F. P., Bosworth, S., Snower, D., & Singer, T. (2021). Navigating motivation: a semantic and subjective atlas of 7 motives. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 568064.

Chiew, K. S., & Braver, T. S. (2011). Positive affect versus reward: Emotional and motivational influences on cognitive control. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 279.

Chowdhury, S. M., & Jeon, J. Y. (2014). Impure altruism or inequality aversion?: An experimental investigation based on income effects. Journal of Public Economics, 118, 143–150.

Cohn, A., Engelmann, J., Fehr, E., & Maréchal, M. A. (2015). Evidence for countercyclical risk aversion: An experiment with financial professionals. American Economic Review, 105(2), 860–885.

Cohn, A., & Maréchal, M. A. (2016). Priming in economics. Current Opinion in Psychology, 12, 17–21.

Condon, P., Desbordes, G., Miller, W. B., & DeSteno, D. (2013). Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychological Science, 24(10), 2125–2127.

Condon, P., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2013). Conceptualizing and experiencing compassion. Emotion, 13(5), 817–821.

Conti, G., Heckman, J. J., & Pinto, R. (2016). The effects of two influential early childhood interventions on health and healthy behaviour. The Economic Journal, 126(596), F28–F65.

Cox, J. C., Friedman, D., & Gjerstad, S. (2007). A tractable model of reciprocity and fairness. Games and Economic Behavior, 59(1), 17–45.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2012). Consequences of self-image and compassionate goals. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 229–277.

Crocker, J., & Canevello, A. (2015). Relationships and the self: Egosystem and ecosystem. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. A. Simpson, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology (vol. 3, pp. 93–116). American Psychological Association.

Davis, D. D., & Holt, C. A. (1993). Experimental Economics. Princeton University Press.

Dimant, E. (2022). Hate trumps love: The impact of political polarization on social preferences. Working Paper.

Dimant, E., & Hyndman, K. (2019). Becoming friends or foes? How competitive environments shape altruistic preferences. Working Paper.

Drouvelis, M., Metcalfe, R., & Powdthavee, N. (2015). Can priming cooperation increase public good contributions? Theory and Decision, 79(3), 479–492.

Dufwenberg, M., & Kirchsteiger, G. (2004). A theory of sequential reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 47(2), 268–298.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Bustamante, D., Mathy, R. M., Miller, P. A., & Lindholm, E. (1988). Differentiation of vicariously induced emotional reactions in children. Developmental Psychology, 24(2), 237–246.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Schaller, M., Miller, P., Carlo, G., Poulin, R., Shea, C., & Shell, R. (1991). Personality and socialization correlates of vicarious emotional responding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 459–470.

Elliot, A. J., & Covington, M. V. (2001). Approach and avoidance motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 13(2), 73–92.

Engl, F., Riedl, A., & Weber, R. (2021). Spillover effects of institutions on cooperative behavior, preferences, and beliefs. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 13(4), 261–299.

Falk, A., & Fischbacher, U. (2006). A theory of reciprocity. Games and Economic Behavior, 54(2), 293–315.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2002). Why social preferences matter-the impact of non-selfish motives on competition, cooperation and incentives. The Economic Journal, 112(478), C1–C33.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868.

Fischbacher, U., Gächter, S., & Fehr, E. (2001). Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters, 71(3), 397–404.

Frijda, N. H., et al. (1986). The emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Gneezy, U., & Imas, A. (2014). Materazzi effect and the strategic use of anger in competitive interactions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(4), 1334–1337.

Goetz, J. L., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351–374.

Heckhausen, J., & Heckhausen, H. (2010). Motivation und Handeln: Einführung und Überblick. Springer.

Heckman, J., Pinto, R., & Savelyev, P. (2013). Understanding the mechanisms through which an influential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. American Economic Review, 103(6), 2052–2086.

Herrero, N., Gadea, M., Rodríguez-Alarcón, G., Espert, R., & Salvador, A. (2010). What happens when we get angry? Hormonal, cardiovascular and asymmetrical brain responses. Hormones and Behavior, 57(3), 276–283.

Holland, R. W., Hendriks, M., & Aarts, H. (2005). Smells like clean spirit: Nonconscious effects of scent on cognition and behavior. Psychological Science, 16(9), 689–693.

Howarth, E., & Hoffman, M. S. (1984). A multidimensional approach to the relationship between mood and weather. British Journal of Psychology, 75(1), 15–23.

Huber, M., Lechner, M., & Strittmatter, A. (2018). Direct and indirect effects of training vouchers for the unemployed. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 181(2), 441–463.

Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 309–334.

Keele, L., Tingley, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Identifying mechanisms behind policy interventions via causal mediation analysis. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34(4), 937–963.

Krawczyk, M. (2013). Delineating deception in experimental economics: Researchers’ and subjects’ views. Working Paper.

Lang, P. J., & Davis, M. (2006). Emotion, motivation, and the brain: Reflex foundations in animal and human research. Progress in Brain Research, 156, 3–29.

Levenson, R. W. (1999). The intrapersonal functions of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 13(5), 481–504.

Levenson, R. W., Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1990). Voluntary facial action generates emotion-specific autonomic nervous system activity. Psychophysiology, 27(4), 363–384.

McCall, C., Steinbeis, N., Ricard, M., & Singer, T. (2014). Compassion meditators show less anger, less punishment, and more compensation of victims in response to fairness violations. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 424.

McKay, R., Efferson, C., Whitehouse, H., & Fehr, E. (2011). Wrath of god: Religious primes and punishment. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 278(1713), 1858–1863.

Moffatt, P. G. (2015). Experimetrics: Econometrics for experimental economics. Palgrave Macmillan.

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1999). The influence of in-store music on wine selections. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(2), 271–276.

Passarelli, F., & Tabellini, G. (2017). Emotions and political unrest. Journal of Political Economy, 125(3), 903–946.

Pearl, J. (2014). Interpretation and identification of causal mediation. Psychological Methods, 19(4), 459–460.

Persson, E. (2018). Testing the impact of frustration and anger when responsibility is low. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 145, 435–448.

Peysakhovich, A., & Rand, D. G. (2015). Habits of virtue: Creating norms of cooperation and defection in the laboratory. Management Science, 62(3), 631–647.

Pillutla, M. M., & Murnighan, J. K. (1996). Unfairness, anger, and spite: Emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 68(3), 208–224.

Potters, J., & Suetens, S. (2009). Cooperation in experimental games of strategic complements and substitutes. The Review of Economic Studies, 76(3), 1125–1147.

R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

R Core Team. (2020). R: Tools for general maximum likelihood estimation. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Robins, J. M., & Greenland, S. (1992). Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology, 3(2), 143–155.

Roseman, I. J. (2011). Emotional behaviors, emotivational goals, emotion strategies: Multiple levels of organization integrate variable and consistent responses. Emotion Review, 3(4), 434–443.

Rotemberg, J. J. (2005). Customer anger at price increases, changes in the frequency of price adjustment and monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(4), 829–852.

Rotemberg, J. J. (2014). Models of caring, or acting as if one cared, about the welfare of others. Annual Review of Economics, 6(1), 129–154.

RStudio Team. (2015). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. RStudio Inc.

Schulz, J. F., Fischbacher, U., Thöni, C., & Utikal, V. (2014). Affect and fairness: Dictator games under cognitive load. Journal of Economic Psychology, 41, 77–87.

Singer, T., Seymour, B., O’Doherty, J. P., Stephan, K. E., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, C. D. (2006). Empathic neural responses are modulated by the perceived fairness of others. Nature, 439(7075), 466–469.

Small, D. A., & Lerner, J. S. (2008). Emotional policy: Personal sadness and anger shape judgments about a welfare case. Political Psychology, 29(2), 149–168.

Strang, S., Grote, X., Kuss, K., Park, S. Q., & Weber, B. (2016). Generalized negative reciprocity in the dictator game-how to interrupt the chain of unfairness. Scientific Reports, 6, 22316.

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 59(5), 1–38.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458.

Van Kleef, G. A., Van Dijk, E., Steinel, W., Harinck, F., & Van Beest, I. (2008). Anger in social conflict: Cross-situational comparisons and suggestions for the future. Group Decision and Negotiation, 17(1), 13–30.

Van Leeuwen, B., Noussair, C. N., Offerman, T., Suetens, S., Van Veelen, M., & Van De Ven, J. (2017). Predictably angry-facial cues provide a credible signal of destructive behavior. Management Science, 64(7), 3352–3364.

Vohs, K. D., Mead, N. L., & Goode, M. R. (2006). The psychological consequences of money. Science, 314(5802), 1154–1156.

Weber, E. U. (2004). Perception matters: Psychophysics for economists. In I. Brocas & J. Carrilo (Eds.), The Psychology of Economic Decisions (pp. 163–176). Oxford University Press.

Williams, L. E., & Bargh, J. A. (2008). Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth. Science, 322(5901), 606–607.

Winter, E., Méndez-Naya, L., & García-Jurado, I. (2016). Mental equilibrium and strategic emotions. Management Science, 63(5), 1302–1317.

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35(2), 151–175.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the Institute for New Economic Thinking is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Steven J. Bosworth, Felix Gelhaar and Simon Bartke for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Regression tables

See Tables 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16.

Appendix 2: Instructions

1.1 General information

You are participating in a study on economic decision-making and in the following you will be asked to make a number of decisions. Please read the following instructions carefully. You have the opportunity to earn money that will be paid out in private and cash at the end of the study. During the study you are not allowed to talk to the other participants. If you have questions, please raise your hand and one of the experimenters will approach you and answer your question.

At the beginning of the study another participant will be assigned to you. This participant remains the same during the entire experiment. His identity will not be revealed.

The study consists of two parts. At the end of the study one of the two parts will be randomly selected as payoff relevant, i.e., this part will be paid out according to your decisions and the decisions of the other participant. Since you do not know which part of the study is payoff relevant, you should always behave as if the current part would be paid out.

1.1.1 Dictator game

In the first part of the study one of you will participate as participant 1 and the other as participant 2. Before you have to make a decision, you will be informed about your role which is randomly assigned.

In this part of the study 20 Euro have to be divided. Participant 1 can decide which amount he wants to keep for himself from a pre-defined set of alternatives. The remaining amount is transferred to participant 2.

1.1.2 Social dilemma game: General information

In part II of the study you continue playing with the same participant which has been assigned to you in part I. In the following he/she will be referred to as participant B.

In this part of the study your payoff depends on your decision and the decision of the other participant. It consists of 16 rounds, whereas the first round is a test round.

In each round you choose a number between 0.0 and 28.0. Participant B chooses also a number between 0.0 and 28.0. Your payoff depends on both decisions.

The table attached gives information about your payoff depending on your own decision and the decision of participant B in steps of two. The columns contain your possible payoffs for the respective numbers of participant B. Participant B receives the same table.

Additionally, you can calculate your own payoff and the payoff of participant B in more detail with a calculator on your screen. Here you can enter your hypothetical decision and a hypothetical decision of participant B to calculate the hypothetical payoffs.

Please enter your final decision and the expectation regarding the decision of participant B in the corresponding fields. Then click next.

The final payoff of this part of the study is determined by summing up all collected points. If you correctly guessed the decision of participant B (\(+-1\)), you additionally receive 5 points. The points will be converted into Euro according to the following rate: 50 points = 1 Euro.

You have about 1 min to enter your decision.

1.1.3 Social dilemma game: Test round

In the first round, you have the opportunity to get familiar with the task and the calculator. This round is a test round and therefore not payoff relevant.

The payoff calculator is implemented as a slider which can be handled with the mouse or the arrow keys on your keyboard. On the upper slider you can enter your own hypothetical decision and on the lower slider you can enter a hypothetical decision of participant B. Your payoff and the payoff of participant B will be displayed accordingly.

Use this round to understand how your decision affects your payoff and the payoff of participant B. Then enter your decision and the expectation about the decision of participant B in the corresponding fields and click on next.

In several rounds you will be asked additionally which number you would choose based on hypothetical decisions of participant B. Fifteen predefined hypothetical decisions of participant B will be displayed. Your task is to state which number you would choose for each hypothetical decision of participant B.

Again you can use a slider to calculate the payoffs. The fields will be filled automatically with the slider. Please click next when you have entered all decisions.

In these rounds your actual payoff will be randomly determined from your hypothetical decisions and your actual choice. If your hypothetical decision is payoff relevant, your hypothetical decision will be chosen based on the actual decision of participant B. Is this number between the predefined hypothetical decisions of participant B, your number will be linear approximated between the relevant predefined hypothetical decisions of participant B.

Since you do not know which decision will be payoff relevant, you should always behave as if each decision will be paid out (see Fig. 8).

Rights and permissions