Abstract

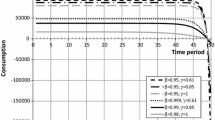

The problem of intertemporal choice arises when outcomes are received in different moments of time. This paper presents an axiomatic model of intertemporal choice when consumption in the previous moment of time contributes to utility evaluation of consumption in the current moment. This model generalizes classic discounted utility theory (also known as constant or exponential discounting) in two ways. First, in every moment of time, a decision maker derives utility not only from current consumption but also from “residual” consumption in the previous moment of time. Second, these utilities are discounted with weights that are essentially a quasi-hyperbolic discounting function. The paper presents an application of the proposed model to the problem of optimal consumption and savings given a fixed income (wealth). When a decision maker derives satisfaction from both instantaneous consumption as well as a share of consumption in the previous moment of time, optimal consumption path is cyclic—periods of relatively high consumption are interchanged with periods of relatively low consumption. These cycles decay over time. Asymptotically, the consumption path exhibits conventional properties (constant, increasing or decreasing over time when a gross interest rate multiplied by discount factor is correspondingly equal to, greater than, or less than one).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allais, M. (1953). Le Comportement de l’Homme Rationnel devant le Risque: Critique des Postulates et Axiomes de l’Ecole Américaine. Econometrica, 21, 503–546.

Baucells, M., & Sarin, R. K. (2007). Satiation in discounted utility. Operations Research, 55(1), 170–181.

Becker, G., & Murphy, K. M. (1988). A theory of rational addiction. Journal of Political Economy, 96(4), 675–701.

Blaschke, W., & Bol, G. (1938). Geometrie der Gewebe: Topologische Fragen der Differentialgeometrie. Springer.

Blavatskyy, P. (2013). A simple behavioral characterization of subjective expected utility. Operations Research, 61(4), 932–940.

Blavatskyy, P. (2016). A monotone model of intertemporal choice. Economic Theory, 62(4), 785–812.

Blavatskyy, Pavlo. (2021). Intertemporal choice as a tradeoff between cumulative payoff and average delay. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 64, 89–107.

Bleichrodt, H., Rohde, K., & Wakker, P. (2008). Koopmans’ constant discounting for intertemporal choice: A simplification and a generalization. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 52, 341–347.

Bradford, D. W., Dolan, P., & Galizzi, M. M. (2019). Looking ahead: Subjective time perception and individual discounting. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 58, 43–69.

Debreu, G. (1954). Representation of a Preference Ordering by a Numerical Function. In R. M. Thrall, C. H. Coombs, & R. L. Davis (Eds.), Decision Processes (pp. 159–165). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Debreu, G. (1960). Topological Methods in Cardinal Utility. In K. Arrow, S. Karlin, & P. Suppes (Eds.), “Mathematical Methods in Social Sciences” Stanford (pp. 16–26). Stanford University Press.

Duesenberry, J. (1952). Income, Savings, and the Theory of Consumer Behavior. Harvard University Press.

Ebert, J., & Prelec, D. (2007). The fragility of time: Time-insensitivity and valuation of the near and far future. Management Science, 53(9), 1423–1438.

Elster, J. (1979). Ulysses and the Sirens: Studies in Rationality and Irrationality Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O'donoghue, T. (2002). Time discounting and time preference: A critical review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 351-401.

Killeen, P. R. (2009). An additive-utility model of delay discounting. Psychological Review, 116(3), 602–619.

Kim, K., & Zauberman, G. (2009). Perception of anticipatory time in temporal discounting. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 2(2), 91–101.

Köbberling, V., & Wakker, P. P. (2003). Preference foundations for nonexpected utility: A generalized and simplified technique. Mathematics of Operations Research, 28, 395–423.

Koopmans, T. (1960). Stationary ordinal utility and impatience. Econometrica, 28, 287–309.

Krantz, D. H., Luce, R. D., Suppes, P., & Tversky, A. (1971). Foundations of Measurement, (Additive and Polynomial Representations) (Vol. 3). New York: Academic Press.

Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 443–477.

Loewenstein, G. (1987). Anticipation and the valuation of delayed consumption. Economic Journal, 97, 666–684.

Loewenstein, G. (1988). Frames of mind in intertemporal choice. Management Science, 34, 200–214.

Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (1992). Anomalies in intertemporal choice: Evidence and an interpretation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107, 573–597.

Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (1993). Preferences for sequences of outcomes. Psychological Revue, 100, 91–108.

Loewenstein, G., & Sicherman, N. (1991). Do workers prefer increasing wage profiles? Journal of Labour Economics, 9, 67–84.

Magen, E., Dweck, C. S., & Gross, J. J. (2008). The hidden-zero effect: Representing a single choice as an extended sequence reduces impulsive choice. Psychological Science, 19, 648–649.

Manzini, P., Mariotti, M., & Mittone, L. (2010). Choosing monetary sequences: Theory and experimental evidence. Theory and Decision, 69, 327–354.

Phelps, E., & Pollak, R. (1968). On second-best national saving and game-equilibrium growth. The Review of Economic Studies, 35, 185–199.

Pollak, R. A. (1970). Habit formation and dynamic demand functions. Journal of Political Economy, 78(4), 745–763.

Read, D., & Scholten, M. (2012). Tradeoffs between sequences: Weighing accumulated outcomes against outcome-adjusted delays. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(6), 1675–1688.

Ryder, K. E., & Heal, G. M. (1973). Optimal growth with intertemporally dependent preferences. Review of Economic Studies, 40, 1–33.

Samuelson, P. (1937). A note on measurement of utility. The Review of Economic Studies, 4, 155–161.

Samuelson, P. (1952). Probability, utility, and the independence axiom. Econometrica, 20(4), 670–678.

Scholten, M., Read, D., & Sanborn, A. (2016). Cumulative weighing of time in intertemporal Tradeoffs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(9), 1177–1205.

Takahashi, T. (2005). Loss of self-contol in intertemporal choice may be attributable to logarithmic time-perception. Medical Hypotheses, 65(4), 691–693.

Thaler, R. H. (1981). Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Economics Letters, 8, 201–207.

Urminsky, O., & Kivetz, R. (2011). Scope insensitivity and the “mere token” effect. Journal of Marketing Research, 48, 282–295.

Wakker, P. P. (1984). Cardinal coordinate independence for expected utility. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 28, 110–117.

Wakker, P. P. (1988). The algebraic versus the topological approach to additive representations. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 32, 421–435.

Wakker, P. P. (1989). Additive Representation of Preferences, A New Foundation of Decision Analysis. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Wathieu, L. (1997). Habits and anomalies in intertemporal choice. Management Science, 43(11), 1552–1563.

Wathieu, L. (2004). Consumer habituation. Management Science, 50(5), 587–596.

Zauberman, G., Kim, K., Malkoc, S., & Bettman, J. (2009). Time discounting and discounting time. Journal of Marketing Research, 46, 543–556.

Funding

Pavlo Blavatskyy is a member of the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Chair, which is part of LabEx Entrepreneurship (University of Montpellier, France) and funded by the French government (Labex Entreprendre, ANR-10-Labex-11–01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Proof of Proposition 1

It is relatively straightforward to show that utility function (2) satisfies axioms 1–4. We shall prove only the sufficiency of these axioms. If all moments of time are null, then proposition 1 holds trivially by setting u(x) = 0 for any x (discount factors could be arbitrary). If only one moment of time t is nonnull, then there is a continuous utility function that represents preferences over outcomes in this nonnull moment of time (Debreu 1954, Theorem I, p.162). Proposition 1 is then satisfied by setting utility function (2) equal to this utility function and letting βt be strictly positive. If two moments of time are nonnull, then by setting s = t and w = y in Axiom 4 we obtain a hexagon or Thomsen-Blaschke condition (Wakker 1984, p.112): whenever \(a_{t} {\varvec{x}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)≽\(b_{t} {\varvec{y}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\), \(a_{t} {\varvec{y}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)≽\(c_{t} {\varvec{x}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\), and \(b_{t} {\varvec{z}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)≽\(a_{t} {\varvec{y}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\) then \(a_{t} {\varvec{z}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)≽\(c_{t} {\varvec{y}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\). Additively separable utility representation (2) is then due to Hauptzatz über Sechseckgewebe (Blaschke and Bol, 1938, p. 10; Debreu 1960) and Theorem 15 in Krantz et al. (1971, Section 6.11.2). If more than two moments of time are nonnull, then preference relation ≽ satisfies ordinal independence (\(a_{t} {\varvec{x}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)≽\(a_{t} {\varvec{y}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\) implies \(b_{t} {\varvec{x}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)≽\(b_{t} {\varvec{y}}^{{\varvec{\alpha}}}\)) due to Lemma 2 in Blavatskyy (2013). Additively separable utility representation (2) is then due to Theorem 3 in Debreu (1960) and Theorem 15 in Krantz et al. (1971, Section 6.11.2).

Q.E.D.

3.1 Proof of Proposition 2

A preference relation ≽ satisfies axioms 1–4 if and only if it admits representation (2) due to Proposition 1. It is relatively straightforward to show that utility function (1) satisfies axiom 6. It remains to show that when preferences are represented by utility function (2) and Axiom 6 holds then they are indeed represented by utility function (1).

Let us consider two streams such that \(\left( {x_{0} , x_{1} , x_{2} ,x_{3} ,x_{4} \ldots , ,x_{T} } \right)\sim \left( {x_{0} , x_{1} ,y_{2} ,x_{3} ,x_{4} \ldots , ,x_{T} } \right)\). If preferences are represented by utility function (2) then this preference indifference implies

which can be rearranged as

If Axiom 6 holds, then we must also have \(\left( {x_{1} , x_{2} ,x_{3} , \ldots , ,x_{T} ,x_{0} } \right)\sim \left( {x_{1} ,y_{2} ,x_{3} , \ldots , ,x_{T} ,x_{0} } \right)\). If preferences are represented by utility function (2), then this preference indifference implies

which can be rearranged as

Dividing this equation by Eq. (4) yields result \(\beta_{3} = \beta_{2}^{2} /\beta_{1}\). Iterating the same argument for subsequent moments of time we obtain that \(\beta_{t} = \beta_{2}^{t - 1} /\beta_{1}^{t - 2}\) for all t ∊ {1, …, T-1}. Finally, since utility function is unique up to a positive affine transformation, we can divide by \(\beta_{0}\) to obtain the conventional normalization that utility in the current moment of time is not discounted.

Q.E.D.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Blavatskyy, P.R. Intertemporal choice with savoring of yesterday. Theory Decis 94, 539–554 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-022-09898-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-022-09898-5