Abstract

Our ordinary conception of imagination takes it to be essentially a conscious phenomenon, and traditionally that’s how it had been treated in the philosophical literature. In fact, this claim had often been taken to be so obvious as not to need any argumentative support. But lately in the philosophical literature on imagination we see increasing support for the view that imagining need not occur consciously. In this paper, I examine the case for unconscious imagination. I’ll consider four different arguments that we can find in the recent literature—three of which are based on cases and one that is based on considerations relating to action guidance. To my mind, none of these arguments is successful. I conclude that the case for postulating unconscious imagining has not yet been well motivated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Our ordinary conception of imagination takes it to be essentially a conscious phenomenon. Traditionally, that’s how it has been treated in the philosophical literature as well. In fact, this claim has often been taken to be so obvious that it was thought not to need any argumentative support. To give just one example, in the context of distinguishing imagination from supposition, Alan White claims that “we can suppose consciously or unconsciously, but not imagine unconsciously” (1990, p. 145). Having made this statement, he moves on—apparently thinking that nothing further needs to be said about the matter.

Lately, however, the philosophical literature on imagination reveals increasing support for the view that imagining need not occur consciously. Theorists who accept the existence of unconscious imagination or something very much like it include Kendall Walton (1990), Alvin Goldman (2006), Jennifer Church (2008), Neil Van Leeuwen (2011, 2014), Bence Nanay (2013), Shannon Spaulding (2016), Berit Brogaard and Dimitria Gatzia (2017), and Ema Sullivan-Bissett (2019). Though some of these theorists assume without argument that imagination can be unconscious, many of them do offer support for the claim.

In this paper, I want to examine the philosophical case for unconscious imagination. I will focus on four different sets of considerations that have been offered to motivate its existence. As I’ll argue, none of these considerations are successful. Although it’s possible that alternative lines of defense could be mounted, given the current state of the debate it seems that the suggestion that we need to postulate unconscious imagining has not been well motivated.

The plan for the paper is as follows. In Sect. 1, I’ll start with a discussion of the point at issue in the debate, i.e., what does it mean to say that imagination is unconscious? In the subsequent sections, I examine four different defenses of this claim. As we will see, all four of these defenses share a common over-arching strategy. They each attempt to show that we cannot adequately explain an agent’s behavior and/or mental states unless we attribute states of unconscious imagining to the agent. Three of the four defenses focus on specific cases or types of cases. The first concerns certain instances of “as-if” behavior, i.e., cases in which one behaves as if one believes something that one does not in fact believe. The second concerns extended imaginative projects, and the third concerns engagement with fiction. I take these up respectively in Sects. 2–4. The fourth defense, which I take up in Sect. 5, relies not on specific cases or types of cases but on more general considerations involving action-guidance. Having shown each of these defenses to be unsuccessful, I offer some short concluding remarks in Sect. 6.

1 Understanding the issue

Consider the definition offered by Shen-yi Liao and Tamar Gendler to open their entry on imagination in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: “To imagine is to represent without aiming at things as they actually, presently, and subjectively are.”Footnote 1 Since representational states, as a general matter, can be either conscious or unconscious, this definition alone does not settle the question whether imagination must be conscious.Footnote 2 Traditionally, however, philosophers have taken imagining to be a conscious phenomenon. Aristotle’s account of imagination, or phantasia, treated it as a conscious presentation of sensory content.Footnote 3 Descartes’ view of imagination as a conscious phenomenon follows from his more general view that all modes of thought are essentially conscious. For Hume, imagining is classified as a species of ideas, one of the two categories (alongside impressions) of our conscious mental states. Finally, a similar presupposition about the conscious nature of imagining is deeply embedded in the phenomenological tradition, with both Husserl and Sartre treating imagination as a mode of consciousness.Footnote 4

As noted above, however, over the past three decades this presupposition has been increasingly called into question. In light of the vast philosophical attention that has been devoted to the nature of consciousness during this same period, one might naturally expect that the first step taken by those arguing for unconscious imagination would be to clarify the notion of consciousness at issue. It’s by now well known that philosophers and scholars in cognate disciplines use the term “consciousness” in a variety of different senses to pick out a variety of different phenomena. For example, to draw on a distinction developed by David Chalmers (1996), the term is sometimes used in a phenomenal sense, to pick out qualitative properties of mind, and sometimes in a psychological sense, to pick out one or more of a number of psychological properties of mind.Footnote 5 Among the ways that a state may be conscious in this latter psychological sense are for it to be accessible to introspection, to be the subject of attention, or be poised for behavioral control. So which sense or senses of consciousness do philosophers have in mind when they deny that imagination must be conscious?

Unfortunately, proponents of the case for unconscious imagination have not been as clear about this issue as we might like. In many cases, the question of what is meant by “conscious” or “unconscious” is never explicitly addressed—there is no attempt at clarification and no reference to (let alone discussion of) the philosophical literature on consciousness. Perhaps the most extreme example of this is Goldman, who simply notes that imagining can be either “conscious or covert” without any further elucidation of what is meant by this (2006, p. 151).

In fact, to some extent the claim that imagination can be unconscious is likely not univocal but rather has a meaning that shifts somewhat from one argument to another. Yet it is important to note that, in the imagination literature, the arguments I will be considering are regularly grouped together and taken to be defenses of the same claim. For example, Spaulding (2016) lists Church, Goldman, Nanay, Van Leeuwen, and Walton as proponents of unconscious imagination. Sullivan-Bissett (2019) lists Church, Goldman, Spaulding, and Van Leeuwen; she also notes that Nanay “might” be an additional proponent. Moreover, even if there is not always a clearly delineated shared target across all of these arguments, there does seem to be an important commonality underlying them. In particular, all of the arguments seem to concern a particular kind of psychological consciousness, namely, what we might think of as consciousness-as-awareness.

As we will see, sometimes the point is put in terms of conscious awareness (i.e., that imagining can occur outside of conscious awareness) whereas sometime it is put in terms of introspective awareness (i.e., that imagining can occur outside of introspective awareness). A fine-grained analysis of consciousness might treat these two senses of awareness as different, particularly if one is skeptical about the notion of introspection. But for our purposes, it seems reasonable to treat them as picking out at least roughly the same phenomenon, and that is how I will proceed.Footnote 6 For the purpose of this discussion, I will assume that proponents of unconscious imagination are at least minimally committed to the claim that imagination can occur outside of awareness.

Some philosophers who deny that imagination must be conscious go even further than this minimal commitment. For example, it seems likely that the unconscious imaginings posited by Neil Van Leeuwen are meant not only to occur outside of conscious awareness but also to lack phenomenal properties. This is evident from Van Leeuwen’s comment for example that such imaginings are not part of conscious experience (2011, fn 4).

In most discussions, however, the focus seems to be limited to the more minimal claim about conscious awareness. This is especially true in Church’s work. When she takes up the question of whether unconscious imaginings can become conscious, she explicitly casts the discussion in terms of whether these imaginings are ones of which the imaginer can become aware.Footnote 7 But Church is also explicit that, in her view, imaginative states that are outside of conscious awareness may still have phenomenal properties (2008, see especially pp. 393–394).

Like Church, Brogaard and Gatzia also focus on conscious awareness. This becomes especially apparent in their claim that imaginative abilities can occur “at a level below conscious awareness.” (Brogaard & Gatzia, 2017, p. 1) A similar focus is found in Sullivan-Bissett, who notes that “by unconscious I mean not available to introspection”; moreover, many of her subsequent remarks about unconscious imagination are cast in terms of a lack of awareness. Sullivan-Bissett also aligns herself with other proponents of unconscious imagination such as Church (though she does not commit herself to endorsing Church’s arguments).

Complications arise, however, when we turn to the work of Walton and Nichols. Walton’s discussion is not cast in terms of conscious/unconscious imagination, but in terms of occurrent/nonoccurrent imagination. Nichols’s discussion is cast in terms of explicit/implicit (or tacit) imagination. I do not take these various distinctions to be identical. A state’s being conscious is not the same thing as its being occurrent or explicit—even when we focus on consciousness just in the sense of conscious awareness. Walton himself makes this very point when he notes a suspicion “that occurrent imaginings need not be conscious.” (Walton, 1990, p. 18).Footnote 8

Faced with these complications, one might naturally wonder why I would bother to consider the arguments offered by Walton and Nichols. Why not just stick to the arguments that proceed expressly in terms of unconscious imagination? I have two different reasons for my inclusive strategy. First, even though the various distinctions just mentioned are not identical, there do seem to be important connections among them. As Gary Bartlett has noted in a recent discussion of occurrent states, “That conscious states are necessarily occurrent would seem to be one of the few features of conscious states on which there is total agreement.” (Bartlett, 2018, p. 2) In fact, Bartlett goes so far as to call this claim a “platitude.” (2018, p. 7) Perhaps there can be occurrent states of which we are not consciously aware, but there cannot be states of which we are consciously aware that are not occurrent.Footnote 9 A similar point seems to apply to the distinction between explicit and implicit states, i.e., there cannot be conscious states—states that are part of our conscious awareness—that are merely implicit. If this is right, then arguments that imagination can be nonoccurrent or implicit would entail that imagination can be outside of conscious awareness.

This leads to the second reason for my inclusive strategy. Perhaps because of the entailment just noted, proponents of unconscious imagination often align themselves with Walton and Nichols and take their arguments to add weight to the case for unconscious imagination. I thus feel obligated to consider these arguments along with the arguments that are specifically directed at unconscious imagination. Strategically, it is important that I cast a broad net; if I didn’t, my opponents would (rightfully) accuse me of cherry-picking my targets. As we will see, however, even with the net cast broadly, we do not find any arguments that are successful.

I now turn directly to the arguments themselves.

2 Explaining behavior: the case of the prying parent

One influential defense of unconscious imagining comes from Jennifer Church (2008), who describes several cases in which it seems that we cannot fully explain the behavior of an agent without positing the existence of unconscious imagining. Church’s cases present us with situations in which an agent behaves in a way that doesn’t match her beliefs (whether conscious or unconscious) or her conscious imaginings. It thus looks like we need some other kind of explanation for her behavior. Church invokes unconscious imagination to play this explanatory role.

I’ll focus on just one of Church’s cases, what she calls the case of the prying parent, since the same considerations would apply to the other cases she discusses. In this scenario, a mother searches her child’s room while the child is away and no one else is home. Church describes the mother’s behavior as follows:

As she searches the room, she steps softly and keeps her face angled toward the door; her body is visibly tense. Her movements are not those of an officer investigating the scene of a crime so much as those of a stealthy burglar. She does not want anyone to know that she is going through her child’s things in this way. (Church, 2008, p. 380)

As Church sets up the case, the mother is alone in the house and is aware of this fact. She does not believe that anyone else is in the house while she’s carrying out her search. According to Church, the mother also does not consciously imagine that someone else is in the house while she’s carrying out her search. Importantly, however, the mother behaves as if there is someone else in the house and as if she were a burglar. How are we to explain this behavior? Why is she sneaking about? Church concludes that we can best understand the situation by seeing the prying parent as unconsciously imagining that someone else is in the house and unconsciously imagining that she’s a burglar, i.e., the prying parent is indeed imagining these things even though she is not consciously aware of doing so.

Church’s strategy thus seems to involve an inference to the best explanation. We have a phenomenon in need of explanation, namely, the mother’s “as-if” behavior. She’s behaving as-if someone is in the house even though she neither believes nor consciously imagines that someone is in the house. In Church’s view, the best available explanation requires positing the existence of unconscious imagining. For the argument to succeed, Church must establish two things. First, she must show that (1) the relevant unconscious imaginings offer an adequate explanation of the mother’s behavior. Second, she must show that (2) there is no equally adequate alternative for explaining that behavior. Let’s take these in turn.

Behind (1) lies an important presupposition. In order for Church’s explanation in terms of unconscious imagining to be plausible, Church must be presupposing that unconscious imagining, were it to exist, would be the kind of mental state that could explain behavior. This presupposition may strike some as nontrivial. But for the purpose of evaluating this argument, I’ll grant this presupposition and won’t quarrel with (1).Footnote 10

Instead, I want to focus on (2), a claim that strikes me as problematic. To my mind, there are several other plausible explanations of the mother’s behavior that are available to us, explanations that rely on other beliefs that the mother might plausibly be said to have. For example, the mother might believe that parents prying in their children’s room usually behave in a stealthy manner, or perhaps even that they should behave in a stealthy manner. Either of these beliefs would explain her behavior.

Alternatively, the mother might simply be acting overcautiously. Though she doesn’t believe that anyone else is in the house, she’s been surprised before when she’s believed that the house was empty and it was not. If someone else were to be in the house without her knowledge, this way of behaving would make it less likely that her prying would be detected. So the mother believes that she should be stealthy just to be safe and thus acts accordingly. This kind of caution strikes me as entirely common. People engage in this kind of “just to be safe” behavior all the time. Someone might not believe that there’s anyone in the hallway outside their office to overhear them when they’re having a confidential phone conversation, but they still talk quietly just in case. Someone might not believe that they left the front door unlocked, but they go back downstairs to check it just in case. When asked why they behaved the way they did, this seems like the way they would probably explain themselves.

Given the availability of these explanations in terms of belief, Church’s case doesn’t seem to force us to postulate unconscious imaginings. These alternative explanations are at least as successful as the explanation involving unconscious imagining, and perhaps even more so. The case of the prying parent is thus unsuccessful.

Before moving on, it’s worth making one further point. If we consider this case carefully, I think we may start to reconsider whether the mother might actually be engaging in some conscious imagining after all. Though Church tries to block this assumption, once we start to think about what would most likely be going on when a prying parent behaves in that sneaky way, it may start to seem plausible to think of her as (consciously) imagining that someone else is in the house. When I try to really fix on this kind of case, the more I think about the mother’s sneaky behavior the more I think that she might well be (consciously) imagining her son coming up the stairs, or standing in the hallway, or surprising her unawares. Thus, we may start to wonder whether the hypothetical as described is really coherent.

3 Extended imaginative projects: the case of Fred’s daydream

A different defense of unconscious imagination, one deriving from the work of Kendall Walton (1990), proceeds by consideration of extended imaginative projects. In such projects, it’s hard to see how all of the parts can be consciously imagined at once. Consider Walton’s discussion of what I’ll call the case of Fred’s daydream: Suppose Fred imagines winning the lottery and using it to finance a successful political campaign; he then imagines that while in office he wins the affection and admiration of the populace and that he ultimately goes on to retire to a villa in southern France. As Walton goes on to note:

After Fred has occurrently imagined himself becoming a millionaire by winning the lottery and has gone on to think about his political career and retirement, he doesn’t cease imagining that he won the lottery. His imagining this is a persisting state that begins when the thought occurs to him and continues, probably, for the duration of the daydream. After the initial thought it is a nonoccurrent imagining which forms a backdrop for later occurrent imaginings about his political career and retirement. (Walton, 1990, p. 17)

Presumably, the reasoning goes something like this. At this late stage of the imaginative project, Fred does not have an occurrent imagining that he won the lottery. Nor does Fred believe that he won the lottery. Yet the content “that he won the lottery” is still doing work in his imaginative project. Thus, in order best to explain this fact, we should conclude that Fred is nonoccurrently imagining that he won the lottery. In light of Bartlett’s platitude (see Sect. 1) that states must be occurrent in order for them to be the subject of conscious awareness, we can conclude that Fred’s imagining is not conscious.

Interestingly, Walton himself does not seem to draw this conclusion. After discussing the case of Fred’s daydream—a case that he takes to establish the existence of nonoccurrent imaginings, he notes the following: “It should be clear that nonoccurrent, nonepisodic imaginings are not necessarily unconscious ones. We may well be at least nonoccurrently aware of them.” (Walton, 1990, p. 18) As this suggests, Walton does not accept Bartlett’s platitude, so he does not take the fact that Fred’s imagining is nonoccurrent to show that Fred’s imagining is unconscious.That said, many proponents of unconscious imagination do seem to accept Bartlett’s platitude and take Walton’s discussion as support for their view. Thus, in line with the inclusive strategy that I outlined in Sect. 1, I treat the case as presenting an argument for unconscious imagination.

Here again we have an argument that can be best understood as an inference to the best explanation. In Church’s case of the prying parent, what needed explanation was the parent’s behavior. In contrast, in the case of Fred’s daydream what we’re trying to explain is the work done by the content “that he won the lottery” in the later stages of the imagining once the content is no longer occurrent before his mind.

In this case, I don’t see any motivation to claim that Fred might really be consciously imagining the relevant content, i.e., that this is something of which he is consciously aware. And of course, he doesn’t believe that he’s won the lottery. But, as with the case of the prying parent, there might well be other beliefs that provide us with an alternative explanation that proceeds without invoking unconscious imagination. For example, Fred may well believe something like the following:

Things imagined at the start of an extended imaginative project are, unless explicitly cancelled, operative throughout the entire imaginative project.

This belief is presumably not occurrent. In fact, it seems like the kind of thing we might naturally think of as an implicit understanding.Footnote 11 But this kind of belief or understanding need not be occurrent in order to explain what it needs to explain.Footnote 12 Here it’s worth noting that we presumably have this same kind of implicit understanding in all sorts of domains. For example, when we’re engaged in argumentation, we presumably understand that premises offered at the start of an extended sequence of reasoning are, unless explicitly cancelled, in effect throughout the entire sequence of reasoning.

Perhaps, however, this analogy to reasoning suggests a way that one might try to bolster the case for non-occurrent (and hence unconscious) imagining.Footnote 13 One might consider the opening moves in Fred’s daydream to be similar to the opening moves in a piece of reasoning. Often when one starts a piece of reasoning one makes certain suppositions for the sake of argument. To give just one example, in a reductio proof one might suppose P in an effort to show that P must be false. These opening suppositions need not be occurrent throughout the entire piece of reasoning, and likewise, Fred’s opening supposition—what we might think of as an imaginative supposition—need not be occurrent throughout the entire imaginative project. So doesn’t this show that imagining can be non-occurrent (and hence unconscious)?

To my mind the answer is no. There is strong consensus among philosophers of imagination—including philosophers who are proponents of unconscious imagination—that imagination is a distinct state from supposition—see, e.g., White (1990), Moran (1994), Gendler (2000), Kind (2001), Doggett and Egan (2007) and Balcerak Jackson (2016).Footnote 14 Not only are the two states thought to be different on phenomenological grounds, but they are also thought to play different functional roles. For example, while imagination typically gives rise to affective states, supposition does not. Another difference concerns the comparative ease with which we produce states of these types. While there are various propositions that are difficult to imagine or that generate imaginative resistance, we do not seem to experience similar difficulty or resistance with respect to supposition.Thus, even if Fred’s daydream can be explained by the existence of a nonoccurrent supposition, that does not show that there can be nonoccurrent imagination.

In fact, this point about supposition ends up hurting the case for unconscious imagination more than it helps, for it serves to point us toward a second and different alternative to Walton’s explanation of the work done by the content “that he’s won the lottery” at the later stages of Fred’s daydreams. In fact, I think the two alternative explanations—the one I initially proposed involving background beliefs, and the one we next considered involving supposition—may even be seen as working together. Recall that the background belief concerned certain content being operative throughout an entire imaginative episode. We might well use the notion of supposition to help explain what this means: content is operative as long as it’s being supposed, whether consciously or unconsciously.

Given the existence of both these alternative explanations, whether taken singly or together, it’s hard to see why we would be forced to accept unconscious imagination to accommodate this kind of example. For that to be the case, the explanation that Walton offers, that is, the explanation that invokes nonoccurrent (and hence unconscious) imaginings, would have to be more plausible than these alternatives, but there’s no reason to think that is the case.

In support of this claim, let me offer one reason to be suspicious of the Waltonian explanation. Insofar as the explanation might initially seem attractive, it’s because it seems implausible to claim that Fred continues for a significant length of time to occurrently imagine that he’s won the lottery. That content just doesn’t remain before his mind that long. But now the question arises: How long do these nonoccurrent imaginings last? Walton suggests that it’s “probably” for the duration of the daydream. But reflection on this issue shows that it is hard to come up with a principled way to answer the question.

Compare beliefs that are not occurrent. As noted by David Truncellito (n.d.), “The majority of an individual’s beliefs are non-occurrent; these are beliefs that the individual has in the background but is not entertaining at a particular time.” Importantly, however, such beliefs are always in the background. Even when someone isn’t thinking about arithmetic, they still believe nonoccurrently that 2 + 3 = 5, and even when someone isn’t thinking about animals, they still nonoccurrently believe that dogs are mammals. One always has these beliefs, even when they are not occurrent before the mind. They are relatively stable, long-lasting states.Footnote 15 But non-occurrent imaginings of the sort in which Fred is allegedly engaged are not similarly stable, long-standing states. Two years later, or even two hours later, he presumably does not continue to nonoccurrently imagine that he won the lottery.

Suppose that Fred engaged in the daydream described above on Monday. And now suppose that on Tuesday, Fred engages in a different daydream. This one starts off with his losing the lottery but then getting a surprise inheritance. He goes on to imagine that he uses the inheritance to finance a successful political campaign, and so on. The imagined scenario continues exactly as the previous day, with his earning the affection and admiration of the populace while in office before he ultimately goes on to retire to a villa in southern France. Applying Walton’s analysis to this case, during the late stages of the Tuesday daydream Fred is nonoccurrently imagining that he didn’t win the lottery. But presumably he’s not at the same time still nonoccurrently imagining contents from his Monday daydream, such as the claim that he won the lottery. That earlier non-occurrent imagining must have disappeared.

How do we explain this? I assume that the proponent of these nonoccurrent imaginings would suggest that they are tied to the overall imaginative exercise and, if not explicitly cancelled, last until that episode is completed. But that can’t be right. Once again, compare nonoccurrent beliefs. Generally, we expect that nonoccurrent beliefs are capable of being brought to conscious awareness, at least in principle, so it seems that something similar should be true of nonoccurrent imaginings. But in a long and complicated daydream, in the later stages of the imaginative episode Fred may have completely forgotten some of the things that he had imagined in its earlier stages. If the nonoccurrent imaginings can’t be brought to conscious awareness in those later stages of the imaginative episode, then it seems implausible that they still exist. So it seems that we can’t explain the disappearance of nonoccurrent imaginings by tying it to the end of the imaginative episode.

In raising these questions, I don’t mean to suggest that they are unanswerable. Perhaps a full theory of unconscious imagining could work out the relevant details. But with no such theory yet on offer, unconscious imagining looks to be a very puzzling state, and this counts against the plausibility of invoking it to explain what’s going on in the case of Fred’s daydream (or in other cases of extended imaginative projects). At the very least, these questions make it hard to deny that the alternative explanation I offered above to account for Fred’s daydream is at least as explanatorily successful as Walton’s explanation. Given the availability of this alternative explanation that does not invoke unconscious imagination, and given that it is at least as explanatorily successful as the one Walton offers, the case of Fred’s daydream does not seem to force us to postulate unconscious imaginings.

4 Engagement with fiction

In his famous paper “Truth in Fiction,” David Lewis argues that there are many statements that are true in a fiction even if they are not explicitly stated in that fiction. For example, in the Sherlock Holmes stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, readers are told explicitly that Sherlock Holmes lives at 221b Baker Street. Given that this is true in these stories, Lewis argues that it is also true in these stories that Holmes lives closer to Paddington Station than he does to Waterloo Station: “A glance at the map will show you that his address in Baker Street is much nearer to Paddington. Yet the map is not part of the stories; and so far as I know it is never stated or implied in the stories themselves that Holmes lives nearer to Paddington.” (Lewis, 1978, p. 41) According to Lewis, the following claims are also true of the Holmes stories, even though none of them is ever made explicit: “that Holmes does not have a third nostril; that he never had a case in which the murderer turned out to be a purple gnome; that he solved his cases without the aid of divine revelation; that he never visited the moons of Saturn; and that he wears underpants.” (Lewis, 1978, p. 41).

On the standard philosophical account of our engagement with fiction, readers engage with works of fiction by imagining the claims there put forth (see e.g., Walton, 1990; Currie, 1990). When the text says, “Holmes returned to his flat at 221b Baker Street,” the reader explicitly imagines that Holmes returned to his flat at 221b Baker Street. Combining this view with the Lewisian account of truth in fiction, we are led to an argument for the existence of unconscious imagination. Presumably most readers engaging with the Holmes stories never explicitly imagine that Holmes wears underpants, and likewise for most if not all of the other claims about Holmes mentioned above. On the Lewisian account, these claims are true in the fiction. But we might also be inclined to say something further: Not only are these claims true in the fiction, but also readers take these claims to be true in the fiction (or at least readers are inclined to take these claims to be true in the fiction). More generally, when readers engage with fiction, there are various claims about the characters and the events that are never explicitly imagined and yet that are taken by readers to be true in the fiction. In order to explain this, the natural suggestion seems to be that these claims are implicitly (hence, unconsciously) imagined by the readers.

Lewis himself does not offer this kind of argument. In offering his account of truth in fiction, he does not take up the question of what readers imagine, consciously or not. But this line of argument can be found elsewhere in the literature on imagination, perhaps most notably in a paper by Shaun Nichols (2004).

Nichols comes to this issue in the course of arguing that imagination and belief operate within a “single code.” If we engage in implicit imagination, this fact has to be explained. Nichols thinks that his single code hypothesis has an explanatory edge in this regard: We are already committed to the existence of tacit beliefs, so however we are to account for them, we can extend the account to tacit imaginings as well. He then offers a quick argument in support of the claim that there are such tacit imaginings. The argument relies on an example drawn from the Arthurian story Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. In this story, a mysterious knight arrives at King Arthur’s court and issues a challenge: He will allow anyone in the hall to strike him with his axe on the condition that the person in turn will agree to give him the right to deal them a blow in return in one year’s time. Sir Gawain takes on the challenge. Grabbing hold of the axe, he chops off the knight’s head. But then, to the amazement of everyone there:

The knight neither faltered nor fell; he started forward with out-stretched hand, and caught the head, and lifted it up; then he turned to his steed, and took hold of the bridle, set his foot in the stirrup, and mounted. His head he held by the hair, in his hand. Then he seated himself in his saddle as if naught ailed him, and he were not headless.Footnote 16

As Nichols notes, this turn of events comes as something of a surprise—not only to Sir Gawain but also to the readers. In order to explain our surprise, Nichols suggests that we must have implicitly imagined that the knight could not survive decapitation. (Nichols, 2004, p. 135).

Suitably generalized, the argument can be schematized roughly as follows:

Nichols’ Argument

-

(1)

Often when we are engaging with fiction we are surprised when some event E happens.

-

(2)

To be surprised by event E, we must in some way have been expecting not E.

-

(3)

That expectation must be captured by an imagining.

-

(4)

In at least some of these cases, we did not consciously imagine not E.

-

(5)

So, in those cases we must have unconsciously imagined not E.

-

(6)

So, unconscious imagination must exist.

The first premise seems unassailable. It also seems clear that we should accept premise 4. In the example from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, it seems unlikely that the reader had explicitly or consciously imagined that the Green Knight could not survive decapitation before Sir Gawain struck him with the axe. More questionable, however, are premises 2 and 3.

In thinking about premise 3, we might wonder why this expectation couldn’t be captured by a belief rather than by an imagining. The strategy here would be similar to the one we employed with respect to Fred’s daydream. Perhaps readers have the belief that authors typically mention notable anomalies about their characters. It’s this belief that gives rise to the relevant expectation, i.e., the expectation that the knight would not survive decapitation. Note that this isn’t to say that the reader must believe, even tacitly, that the Green Knight could not survive decapitation. As mentioned above, the standard philosophical account of our engagement with fiction (following Walton and Currie) sees readers as engaging with fiction by way of imaginings, not by beliefs. But these imaginings are surely situated within a complex tapestry of attitudes, including tacit background beliefs, with which readers approach fiction. My suggestion is that some of these background beliefs include meta-beliefs about how fictions work.Footnote 17

Premise 2 also seems problematic. Nichols’ argument here seems to be relying on a false analysis of surprise. Let’s step back from cases in fiction and consider real life cases of surprise. In real life, does a surprise reaction to some event E show that we must have expected that E would not happen? Consider a surprise party. When someone is surprised by a surprise birthday party, this suggestion would imply that they must have had an expectation (perhaps implicit) along the lines of: “My friends are not going to throw me a surprise party.” This strikes me as implausible, at least in a wide range of cases.

Granted, there will be some cases in which the individual being feted explicitly considers and rejects the possibility that friends would be throwing a surprise party. Maybe the friends have even said they wouldn’t throw a surprise party (“Of course we wouldn’t do that, we know how much you hate surprises!”), and the individual took these reassurances seriously. But in many other cases, the possibility might never have entered the individual’s mind. In such cases, we can better explain their surprise by pointing to their lack of belief about E rather than to an expectation that not E. To be surprised by event E, one need not have an expectation (explicit or implicit) that E will not occur. If this kind of explanation works in real life cases of surprise, then in the case of fiction it seems that we could explain surprise in terms of a lack of imagining about E rather than in terms of an implicit imagining that not E. Nichols’ case thus does not give us reason to believe in unconscious imagination.

Before closing this section, let’s briefly return to the more general considerations about engagement with fiction with which we began. Again, the more general issue arises from the fact that there seem to be claims about fictional characters and events that we take to be true in a fiction even though these claims are never explicitly imagined. Does this mean that they must have been implicitly imagined?

Our discussion of Nichols sheds light on this issue. Consider how one might support the suggestions that various unstated claims are taken to be true by readers of a fiction. Let’s focus on two such claims mentioned by Lewis, namely, the claim that Holmes does not have a third nostril and the claim that Holmes wears underpants. Though I think that both of these claims can be easily handled, I think they need to be treated separately.

First, when it comes to the claim that Holmes does not have a third nostril, I think there’s a sense in which this claim is explicitly considered by readers. In imagining Holmes, and more specifically, in visually imagining him, many readers likely form a mental picture of his face, and that face likely contains a nose with just two nostrils.Footnote 18 Thus, I think it’s fair to say that many readers have likely consciously imagined Holmes as not having three nostrils. There is thus no issue about the fact that readers take this claim to be true in the Holmes’ stories. This kind of example consequently gives us no reason to postulate implicit imagination.

In contrast, most readers of the Holmes stories presumably never consider the issue of whether Holmes wears underpants.Footnote 19 Why does it seem plausible to say that this is a claim they have implicitly taken to be true? Presumably the explanation would go something like the following: Were they to find out that Holmes did not wear underpants, they would be surprised. But as we have just seen, the fact that a reader is surprised by not-E does not entail that they have imagined E. We can explain their surprise by a lack of imagining of not-E. Thus, as with the previous kind of example, this kind of example gives us no reason to postulate implicit imagination.Footnote 20

5 Action guidance

The final kind of argument that we will consider is based on an analogy between perception and imagination. As suggested by Bence Nanay, “Given the various similarities between perception and mental imagery, if perception can be conscious or unconscious, then it is difficult to see what would prevent one from having both conscious and unconscious mental imagery.” (2013, p. 105) Berit Brogaard and Dimitria Gatzia make a similar point:

It has been hypothesized that there is a significant overlap between the perceptual and the imagistic domains. … If this hypothesis is correct, then we should expect visual mental imagery to be parallel to visual perception in various respects. We know, for example, that visual detection abilities do not require conscious vision…, so we should expect imaginative abilities to be executable at a level below conscious awareness as well. (Brogaard & Gatzia, 2017, p. 1)

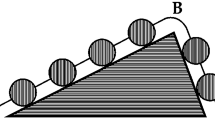

The reasons to believe in perceptual activity that is not conscious stem from the difference between what’s known as vision-for-perception and vision-for-action. In the empirical literature on vision, researchers such as Melvin Goodale and David Milner have argued for the two-systems hypothesis, i.e., that there exist two neural pathways for visual processing—the ventral stream and the dorsal stream. In the dorsal stream, visual information (about a target object, say) is processed via a dedicated visuomotor control system and converted directly into action without any conscious perception of that target’s form (see, e.g., Goodale & Milner, 1992).Footnote 21 This control system is what’s meant by vision-for-action. Whereas vision-for-perception—normal conscious perception—concerns the kind of visual processing that enables you to detect colors, sizes, and shapes of objects, vision-for-action is the kind of visual processing that enables you to guide your movements, such as catching a ball or reaching up to grab a tree branch.

Nanay turns to pretense as one example where we would use unconscious imagery-for-action, what he calls pragmatic mental imagery. Consider a case where I am pretending to be at a cocktail party, and I am pretending that I have a glass of wine in my hand. I consciously imagine the glass. But more also seems to be happening, as Nanay notes:

When I am pretending to raise my glass with nothing in my hand … I also need to have pragmatic mental imagery that allows me to hold my fingers and move my hand in a certain way. This pragmatic mental imagery attributes action properties (weight, shape and spatial location properties) to the imagined glass in my hand. (Nanay, 2013, pp. 117–118)Footnote 22

On Nanay’s view, this pragmatic mental imagery occurs outside of conscious awareness.

In fact, this style of argument is not limited to cases of pretense. Considering ordinary action-guiding contexts, Brogaard and Gatzia have suggested that the mechanisms underlying vision-for-action must include more than just unconscious perceptual processes. They must also involve unconscious imaginative processes. As they argue, when we use action-guiding representations, these seem also to “involve imaginings of the route that needs to be traveled to bypass obstacles and reach an object location,” but we are not consciously aware of any such imaginings. (Brogaard & Gatzia, 2017, p. 6).

My response to the argument from action-guidance takes a divide-and-conquer approach. While the considerations raised do seem to suggest that there are representations at work, it’s not clear that we have reason to believe that these representations are unconscious imaginings. As I will suggest, in some cases they may indeed be imaginings, but these imaginings are ones of which we are consciously aware. In other cases, though one might grant that there are unconscious representations at work, I deny that these should be characterized as imaginings.

In some of Brogaard and Gatzia’s examples, I’m inclined to think that we likely do some of the requisite obstacle-mapping by way of conscious and deliberate imagining. Consider a case in which I have just dropped a glass in the kitchen. There are sharp shards of glass everywhere, and I need to cross the kitchen to get the broom. When I am trying to chart a safe path, I consciously imagine myself stepping this way and then that way, and it’s by these means that I figure out how to avoid the shards of glass underfoot in my path. I think something similar is often true in situations of pretense. Returning to Nanay’s example, I think the pretender may well do considerably more conscious imagining of the shape and size of the glass than he suggests.

This line of response probably won’t account for all cases, however. When the obstacle mapping is extremely quick and complicated, for example, it becomes less plausible that the relevant imaginings are conscious. Thus, to account for these other cases, we need to attend more carefully to the nature of the unconscious representations being posited. As I want now to suggest, when we think about the evidence that Brogaard and Gatzia invoke to make the case for unconscious representations, the representations seem better described as instances of unconscious imagery than as instances of unconscious imagination.

In fact, this is how Nanay himself casts his argument. In offering the kinds of considerations described above, Nanay takes them to show the existence of unconscious mental imagery, not the existence of unconscious imagination.Footnote 23 But unlike Nanay, Brogaard and Gatzia characterize their claim in terms of both mental imagery and imagination, i.e., they talk both of unconscious mental imagery and of unconscious imagination. This makes it more difficult to sort out exactly what they’re arguing. At times, one might be tempted to suppose that they’re using the terms “imagination” and “mental imagery” interchangeably.Footnote 24 If this were how they were using the terms, then, their arguments might be construed as analogous to Nanay’s. We would then have an easy response: Even if such arguments succeed, they show only that there is unconscious mental imagery and not that there is unconscious imagination.

But Brogaard and Gatzia expressly deny that “imagination” and “mental imagery” are interchangeable; in a footnote on the term “mental imagery” they explain that they use it “to refer to both re-experiences of an original stimulus as well as imagination” (Brogaard & Gatzia, 2017, 1 fn1). In other words, they take “mental imagery” to refer to instances of memory as well as to instances of imagination. Indeed, the fact that mental imagery seems to occur in memory as well as in imagination is one reason that philosophers don’t use the terms “imagination” and “mental imagery” interchangeably. Just as someone might employ mental imagery when imagining their unborn grandchild, they might also employ mental imagery when remembering their deceased grandparent. And mental imagery might well be involved in other mental states as well. Someone’s belief that their grandmother had red hair, for example, might well involve an image of her.

Brogaard and Gatzia also seem to be aware of, and to endorse, other arguments from the philosophical literature suggesting we should not identify mental imagery with imagination. One such argument stems from the fact that the contents of the two kinds of representations seem different. Alan White, for example, suggests both that (1) two imaginings of the same thing might involve different images; and that (2) one and the same image might be involved in imagining two different things. In support of (1), he notes that we could use several different images to imagine a sailor scrambling ashore on a deserted island. In support of (2), he notes that “the imagery of a sailor scrambling ashore could be exactly the same as that of his twin brother crawling backwards into the sea, yet to imagine one of these is quite different from imagining the other” (White, 1990, p. 92).Footnote 25 In claiming that an imagining “can represent content over and above what is represented by the visual image, Brogaard and Gatzia seems to accept these sorts of considerations (Brogaard & Gatzia, 2017, p. 11).

Given their acceptance of the distinction between imagination and mental imagery, the fact that Brogaard and Gatzia talk about both counts against treating their arguments as parallel to Nanay’s in scope, i.e., as limited to a case about unconscious mental imagery. The easy response identified above—that their arguments are about only unconscious imagery and not unconscious imagination—may thus seem unavailable. But, that said, I think it might nonetheless be the correct response. A careful reading of their paper suggests that their main concern throughout is not to establish something about the nature of imagination but rather to establish something about the nature of mental imagery.

One indication comes from the fact that of the seven section headings in their paper, none refer to imagination but five refer to imagery (the other two are “Introduction” and “Concluding Remarks”). Moreover, when they summarize their findings in their concluding remarks, the points are all put in terms of imagery, with no reference to imagination. Thus, even though the title of their paper uses the phrase “unconscious imagination,” this does not really match the way they discuss the issue in the paper itself.

But there’s a deeper reason for thinking that their main concern is with mental imagery and not imagination. The arguments of their paper rest on an analogy between “the perceptual and the imagistic domains.” As we have seen, in vision-for-action, the visual representations produced by the dorsal stream and used for action-guidance are not available to consciousness, i.e., they occur outside of conscious awareness. But Goodale and Milner explicitly caution against describing this in terms of unconscious perception. As they note: “Use of that phrase carries an implication that the visual processing could in principle be conscious. The fact is that visual activity in the dorsal stream can never become conscious—so ‘perception’ is just the wrong word to use.” (Goodale & Milner, 2004, p. 191).

For the same reason that “perception” is not the right word to use, then, it seems that “imagination” would not be the right word to use. This point gains further support from reflection on the other contexts in which unconscious imagination was invoked. In all three of the other contexts, the kind of unconscious imagining that has been invoked is meant to be a kind of imagining that’s in principle accessible to consciousness. In those contexts, though the relevant imaginings are claimed to be outside of our conscious awareness, their being so is only a temporary or contingent matter. This makes the unconscious activity that Brogaard and Gatzia posit a very different kind of activity from what Church, Walton, and Nichols posit.

Perhaps Brogaard and Gatzia’s arguments support the existence of unconscious mental imagery. As noted above, their case rests heavily on neuroscientific findings, and I have not here reviewed those findings sufficiently to draw a conclusion one way or the other. But ultimately, for our purposes, that won’t matter. Even if their arguments do make a successful case for the existence of unconscious mental imagery, that would be a very different thing from making a case for the existence of unconscious imagination. And, as I have suggested, they have not intended to offer this latter kind of case. Just as we should not include Nanay in the camp of those arguing for unconscious imagination, we should not include Brogaard and Gatzia in this camp either.

6 Concluding remarks

Having worked through these four sets of considerations, we should now take stock. None of the arguments that we’ve discussed forces us to accept the existence of unconscious imagination. In each case, there are alternate explanations that are equally good. But at this point, one might find a certain line of response tempting: Even if none of these arguments works individually, might there not be enough cumulative weight here to make the case?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, my answer is no. One reason is that it’s not clear that all sets of considerations are making the case for the same kind of phenomenon. In an effort to cast a wide net and be as charitable as possible, I have lumped together arguments talking about imaginings that are unconscious, nonoccurrent, and dispositional. Though this enabled us to consider a greater variety of possible arguments, it also revealed that the mental states discussed may not be the same phenomenon after all, a point that the proponents of unconscious imagination seem to have missed—and this despite the fact that at least some of the participants in these different contexts call upon the arguments from participants in the other contexts.

But there’s also a second reason to reject the cumulative weight argument. In general, what matters first and foremost in establishing a conclusion is argument quality, not argument quantity. When engaging in philosophical discussion, one would laugh at an opponent who said: Yes, I know that all these arguments for my conclusion are bad ones, but I’ve given you four of them! That characterization may be somewhat uncharitable, but the point is that arguments don’t get any better simply by being numerous.

That said, there might be a more charitable way of looking at the argument based on cumulative weight. Suppose we were to construe the dialectic as follows: There’s a lot of explanatory work, in a lot of different contexts, that unconscious imagination (or something very similar) could be doing. It’s not required in any of one of these contexts, but the fact that this very same notion has a role to play in four different contexts makes our inference to the best explanation a bit stronger. After all, analogous kinds of cumulative weight considerations are often invoked in scientific explanations. One way that a scientific theory might gain support is by providing a unifying explanation for many different phenomena. Though its support may be weak in each individual case, the fact that it ties all these disparate phenomena together is a reason to accept it.Footnote 26

To my mind, however, even this version of the cumulative weight argument is unsatisfactory. First, as we’ve noted, the considerations from action guidance do not really seem to relate to unconscious imagination. Rather, they relate to unconscious mental imagery. So we’re really talking about three contexts, not four.Footnote 27 But second and more importantly, we have another equally plausible way to account for all these disparate phenomena, namely, by way of an interplay between conscious imaginings, occurrent beliefs, and nonoccurrent beliefs. We’re not faced with a situation where, unless we invoke unconscious imagination, we have three different contexts where there are otherwise unexplainable phenomena. As I have argued, the phenomena in question can be successfully explained in terms of mental states that we already accept. Thus, as I hope to have shown, the case for unconscious imagination has not been made.Footnote 28

Notes

Some philosophers, myself included, define imagination so that it requires that the representation be imagistic in nature (see Kind, 2001). For the purpose of this paper, however, I remain neutral on this further requirement.

See Sullivan-Bissett (2019) for arguments to this effect. On her view, nothing in the definition of imagination rules out the possibility of unconscious imagination.

For discussion, see Modrak (2016), esp. pp. 16–17.

For discussion, see Brann (1991, pp. 122–138).

See also Block (1995) for a related distinction between phenomenal consciousness (p-consciousness) and access consciousness (a-consciousness).

In explicating how this process might happen, for example, Church notes that an observer might use a process of astute questioning and suggestions to prompt an imaginer to reflect on their behavior and thereby become aware of what they had been imagining (2008, see especially pp. 395–396).

In fact, Walton’s own views about the relationship between the occurrent/nonoccurrent distinction and the conscious/unconscious distinction are complex. I will return to this issue in Sect. 3 below.

For Bartlett’s argument that not all occurrent states need be conscious, see his (2018, pp. 7–9). He cites Alston (1967) and Mele (2003) as making this point with respect to desires. For further support for the claim that states must be occurrent to be the subject of conscious awareness, see Hill (2009, pp. 6–7).

For a brief defense of this presupposition, see Sullivan-Bissett (2019, p. 640).

Thanks to an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

It’s also worth noting that philosophers already accept the existence of beliefs of a very similar sort with respect to imaginative projects. When Fred imagines that he’ll be retiring to the south of France, it’s generally agreed that he need not also imagine that France is in Europe. This content is supplied by his belief that France is in Europe. And Fred is fully aware of this, that is, he presumably has a belief of the sort: Known implications of what has been imagined as part of an imaginative project are, unless explicitly cancelled, operative throughout the entire imaginative project.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pushing me to address this point.

That said, the consensus is not unanimous. See, e.g., Arcangeli (2018).

Cf. Schwitzgebel (2019): “The occurrent belief comes and goes, depending on whether circumstances elicit it; the dispositional [i.e., nonoccurrent] belief endures.”

For the full text, see The Camelot Project: https://d.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/text/weston-sir-gawain-and-the-green-knight.

I owe the phrase “complex tapestry of attitudes” to an anonymous referee.

Not all readers do this, of course. Recent discussion of aphantasia—a condition in which individuals experience an inability (or significantly reduced ability) to produce images voluntarily—suggest that at least some readers engage with fiction without forming any mental images. See, e.g., Zeman et al. (2015).

I should note that I do not have exhaustive familiarity with the entire Holmes’ canon; I am just following Lewis. If there are any scenes in the Holmes stories where Holmes is described as disrobing, then readers might well explicitly imagine Holmes’ underpants. This example would then be handled like the example of the third nostril. But the point I make in the text about the underpants example would still presumably apply to some of the other examples Lewis uses, e.g., that Holmes never visited the moons of Saturn.

Note that nothing that I’ve argued in this section shows that Lewis’s analysis of truth in fiction is incorrect. Lewis does not address the question of what people take to be true in fiction but rather the question of what is true in fiction. Just as people don’t form beliefs about everything that’s true in reality, readers need not form imaginings about everything that’s true in a fiction. It may be true in the fiction that Holmes wears underpants even if readers have never considered the issue and thus cannot be described as taking it to be true.

For the purpose of this paper, I will grant Brogaard and Gatzia’s claim that dorsal vision is unconscious. But it’s worth noting that this claim is not uncontroversial. In a recent paper Wayne Wu (2020) has argued that arguments for unconscious vision based on the two-systems hypothesis are problematic; in particular, he argues that they mistakenly assume the reliability of introspective reports regarding the dorsal stream. If dorsal stream processing turns out to be conscious, then this would undercut arguments like Brogaard and Gatzia’s that defend unconscious imagination on the basis of an analogy to unconscious perception.

Nanay (2021) offers additional considerations tending to show the existence of unconscious mental imagery, considerations relating to unilateral neglect and unconscious priming. But there too, his arguments are cast in terms of imagery and not in terms of imagination. He has confirmed in personal correspondence that he does not take his arguments for unconscious mental imagery to show that unconscious imagination exists.

This kind of usage, though not common in the philosophical literature, is common in the psychological literature.

See Kind (2001) for additional examples.

Thanks to an anonymous referee for pushing me on this point.

Perhaps there might be other relevant contexts as well—for example, were unconscious imagination to exist, it might be helpful in explaining implicit bias (see Sullivan-Bissett, 2019) and low-level mental simulation (see Spaulding 2016). Though I don’t have the space here to address these claims in any detail, I’ll just briefly note that there are many other widely accepted explanations of implicit bias on offer, and the existence of low-level mental simulation is highly controversial.

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at workshops at the University of Geneva (2018) and the University of Toronto (2019) as well as at a colloquium at Ruhr University Bochum (2019). Some of ideas for this paper were initially developed for a presentation on “Consciousness and Imagination” at the Northern California Consciousness Meeting, UC Davis (2016). I am grateful for all of the feedback I received from those audiences. Special thanks are also owed to several anonymous referees for Synthese whose feedback significantly improved the paper.

References

Alston, W. (1967). Motives and motivation. In P. Edwards (Ed.), The encyclopedia of philosophy (Vol. 5, pp. 399–409). Macmillan.

Arcangeli, M. (2018). Supposition and the imaginative realm: A philosophical inquiry. Routledge.

Bartlett, G. (2018). Occurrent states. Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 48(1), 1–17.

Block, N. (1995). On a confusion about a function of consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 18, 227–287.

Brann, E. T. H. (1991). The world of the imagination: Sum and substance. Rowman and Littlefield.

Brogaard, B., & Gatzia, D. (2017). Unconscious imagination and the mental imagery debate. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–14.

Chalmers, D. (1996). The conscious mind. Oxford University Press.

Church, J. (2008). The hidden image: A defense of unconscious imagining and its importance. American Imago, 65(3), 379–404.

Currie, G. (1990). The nature of fiction. Cambridge University Press.

Doggett, T., & Egan, A. (2007). Wanting things you don’t want: the case for an imaginative analogue of desire. Philosophers’ Imprint, 7(9), 1–17.

Gendler, T. (2000). The puzzle of imaginative resistance. Journal of Philosophy, 97(2), 55–81.

Goldman, AIvin. . (2006). Simulating minds: the philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience of mindreading. Oxford University Press.

Goodale, M., & Milner, D. (1992). Separate neural pathways for perception and action. Trends in Neuroscience, 15, 20–25.

Goodale, M., & Milner, D. (2004). Sight unseen: an exploration of conscious and unconscious vision. Oxford University Press.

Hill, C. (1988). Introspective awareness of sensations. Topoi, 7, 11–24.

Hill, C. (2009). Consciousness. Cambridge University Press.

Jackson Magdalena, M. (2016). On the epistemic value of imagining, supposing, and conceiving. In A. Kind & P. Kung (Eds.), Knowledge through imagination (pp. 41–60). Oxford University Press.

Kind, A. (2001). Putting the image back in imagination. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 62, 85–109.

Lewis, D. (1978). Truth in Fiction. American Philosophical Quarterly, 15(1), 37–46.

Mele, A. (2003). Motivation and agency. Oxford University Press.

Modrak, D. (2016). Aristotle on phatasia. In A. Kind (Ed.), Routledge handbook of philosophy of imagination (pp. 15–26). Routledge.

Moran, R. (1994). The expression of feeling in imagination. The Philosophical Review, 103(1), 75–106. https://doi.org/10.2307/2185873

Nanay, B. (2013). Between perception and action. Oxford University Press.

Nanay, B. (2021). Unconscious mental imagery. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0689

Nichols, S. (2004). Imagining and believing: the promise of single code. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 62(2), 129–139.

Schwitzgebel, E. (2019). “Belief.” In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/belief/.

Spaulding, S. (2016). Simulation theory. In Amy Kind (Ed.), Handbook of Imagination (pp. 262–273). Routledge Press.

Sullivan-Bissett, E. (2019). Biased by our imaginings. Mind and Language, 34, 627–647.

Truncellito, D. A., (n.d.) “Epistemology". In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161–0002, https://www.iep.utm.edu/

Van Leeuwen, N. (2011). Imagining is where the action is. Journal of Philosophy, 108(2), 55–77.

Van Leeuwen, N. (2014). The Meanings of ‘Imagine’ Part II: Attitude and Action. Philosophy Compass, 9(11), 791–802.

Walton, K. (1990). Mimesis as make-believe: on the foundations of the representational arts. Harvard University Press.

White, A. (1990). The language of imagination. Basil Blackwell.

Wu, W. (2020). Is vision for action unconscious? Journal of Philosophy, 117(8), 413–433.

Zeman, A., Dewar, M., & Della, S. S. (2015). Lives without imagery - Congenital aphantasia. Cortex, 73, 378–380.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the topical collection "Imagination and its Limits", edited by Amy Kind and Tufan Kiymaz.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kind, A. Can imagination be unconscious?. Synthese 199, 13121–13141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03369-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-021-03369-0