Abstract

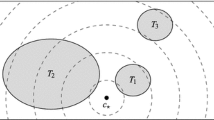

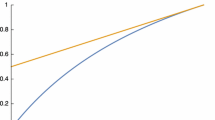

This model explores consensus among agents in a population in terms of two properties. The first is a probability of belief change (PBC). This value indicates how likely agents are to change their mind in interactions. The other is the size of the agents audience: the proportion of the population the agent has access to at any given time. In all instances, the agents converge on a single belief, although the agents are arational. I argue that this generates a skeptical hypothesis: any instance of purportedly rational consensus might just as well be a case of arational belief convergence. I also consider what the model tells us about increasing the likelihood that one agent’s belief is adopted by the rest. Agents are most likely to have their beliefs adopted by the entire population when their value for PBC is low relative to the rest of the population and their audience sizes are roughly three-quarters of the largest possible audience. I further explore the consequences of dogmatists to the population; individuals who refuse to change their mind end up polarizing the population. I conclude with reflections on the supposedly special character of rationality in belief-spread.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for catching poor wording here.

One problem considered by Lehrer and Wagner is the condition under which it is rational to assign someone zero weight, effectively communicating that that agent’s beliefs aren’t worth consideration. Lehrer’s solution is that a person X should assigned a weight of zero to person Y just in case X has no preference between Y’s judgments and that of a random device. See Forrest (1985) and Martini et al. (2013) for discussion.

Lehrer (1976) argues that, as long as each member of the group has some positive regard for every other member of the group, rational disagreement is impossible.

Baumgaertner (2014) is another example.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for suggestions to clarify the ideas in these last two paragraphs.

See Silver (2012) for one man’s love letter to the right Reverend Bayes.

None of these authors have argued that capacity-rationality is necessary for consensus. Even so, a review of the literature would suggest a broad, de facto consensus that capacity-rationality is at work in convergence. So if any of the above authors wish to deny that capacity-rationality is captured in their models, that’s fine! The arguments I develop in this paper would only require a few tweaks to address the descriptive gloss of the models.

This is different from evidence for construct validity as psychologists talk about it (cf. Cronbach and Meehl 1955). There, construct validity is a matter of ensuring that a test actually taps into the hypothetical construct it is intended to tap into. In what follows, I offer conceptual and empirical arguments that the PBC construct has a high degree of empirical plausibility and internal coherence. I happen to mention ways in which an individual’s PBC could be discerned, but only in principle.

The metaphor here is obviously far from perfect. Mugs have a clear market value while beliefs do not. Be that as it may, one plausible explanation for why certain deeply entrenched beliefs are difficult to change is that there is something like an endowment effect at work. Wittgenstein (1953) seems to point in this direction with his concept of a ‘form of life.’

O’Keefe, Ed (March 21, 2014). “The House has voted 54 times in four years on Obamacare. Here’s the full list.” Washington Post

See O’Connor and Weatherall (2019) for fascinating discussion of formal models of propagandists and lobbyists affecting group decision-making processes.

Situationists in ethics and epistemology have turned this insight into a minor industry within philosophy. A soon-to-be dying industry one hopes.

This is, of course, something of a misnomer. Hume was a psychological determinist and hoped that we might one day understand the mind along the lines of classical mechanics.

An assumption of this argument is that opinion dynamics are probabilistic rather than deterministic. This is a reasonable assumption given our best psychological science.

Thanks to Cailin O’Connor for this suggestion.

More precisely: There were on average 331 agents. One of the parameters of the model was population density. Every agent is generated from a patch in the model. Each patch draws a random real number and if it is below the value for population density, then the patch generates an agent. For all runs of the model, the density parameter was set to 0.75.

The conception of belief native to the ABC model has more in common with unique-belief models (e.g. Zollman 2015), a small modification to the ABC model can have agents trading credences as opposed to beliefs. Rather than assign each agent a natural number representing a belief, each agent can be assigned a real number 0 \(\le \) n \(\le \) 1.0 representing a credence held towards a particular belief. The model then runs as usual. Credence adjustment in the revised ABC model is a function of each agent’s PBC rather than (e.g.) weighted averaging. Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for identifying the difference.

Thanks to Dunja Šešelja for the suggestion to make this clearer.

Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this addition.

Another difference of note is the number of pairwise significantly different conditions for time to convergence for the Uniform and Diversity conditions: 29% versus 22%. Humility in the power of computational models prohibits from speculating too much about this difference. But if one were to take a guess at an implication of this finding, it might go: (i) the Diversity Condition is much closer to how things stand in the actual world and (ii) it can be difficult to discern differences in PBCs values from cases of convergence in the actual world.

The population is limited to one hundred agents; this makes the visualization easier to interpret and doesn’t affect any of the underlying philosophical questions.

200,000 timesteps was longer than the longest time to took for models parameterized to PBC ceiling = 0.01 and audience size ceiling = 0.01 to reach consensus.

Maxwell (2003) writes in a footnote, “When I recently drew Thomas Nagel’s attention to these publications, he remarked in a letter, with great generosity: ‘There is no justice. No, I was unaware of your papers, which made the central point before anyone else.’ Frank Jackson acknowledged, however, that he had read my 1968 paper.” The paper to which Maxwell alludes has been cited by philosophers other than Maxwell 11 times, according to Google Scholar. Jackson (1982) has been cited 3130 times and Nagel (1974) 8365 times. ‘Time and chance’ indeed.

This brings new meaning to the old saw, “science advances one funeral at a time.”

See Bramson et al. (2017) for an excellent overview of the polarization literature.

To be clear, these frames were never not cool. It was society that got things wrong.

Thanks to Carlos Santana for the suggestion.

Model created in Netlogo 6.0.1. Data analysis and graphs produced with R 3.5.3 and RStudio. Color palette is from the Viridis package, which renders colors that are both easier for folks with color-vision issues and easier for black and white reproduction. Thanks to Mark Alfino, Nathan Ballantyne, Ted di Maria, Brian Henning, Maria Howard, and Zach Howard for discussion and feedback. Thanks also to Chris Ultican for his willingness to endure thinking through the technical details of the model and the philosophical implications. I’m grateful to the participants of the 2018 Computational Modeling in Philosophy conference at Ludwig Maximilians University for helpful feedback and discussion. Thanks also to the Digital Humanities Initiative at Gonzaga University for financial support. Finally, a special thanks to Michele Lassiter for her unwavering love and support.

References

Abrahamson, E., & Rosenkopf, L. (1997). Social network effects on the extent of innovation diffusion: A computer simulation. Organization Science, 8, 289–309.

Bala, V., & Goyal, S. (1998). Learning from neighbors. Review of Economic Studies, 6, 595–621.

Baronchelli, A. (2008). The emergence of consensus: A primer. Royal Society Open Science. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsos.172189.

Baumgaertner, B. (2014). Yes, no, maybe so: A veritistic approach to echo chambers using a trichotomous belief model. Synthese, 191, 2549–2569.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2003). Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination, No. w9873. National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9873.

Bostrom, N. (2003). Are we living in a computer simulation? The Philosophical Quarterly, 53, 243–255.

Bowers, J., & Davis, C. (2012). Bayesian just-so stories in psychology and neuroscience. Psychological Bulletin, 138, 389–414.

Bramson, A., Grim, P., Singer, D. J., Berger, W. J., Sack, G., Fisher, S., et al. (2017). Understanding polarization: Meanings, measures, and model evaluation. Philosophy of Science, 84, 115–159.

Brunswik, E. (1955a). Representative design and probabilistic theory in a functional psychology. Psychological Review, 62, 193–217.

Brunswik, E. (1955b). In defense of probabilistic functionalism: A reply. Psychological Review, 62, 236–242.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281–302.

Darley, J. M., & Batson, C. D. (1973). From Jerusalem to Jericho: A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 27, 100–108.

DeGroot, M. H. (1974). Reaching a consensus. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 69, 118–121.

Easwaran, K., Fenton-Glynn, L., Hitchcock, C., & Velasco, J. D. (2016). Updating on the Credences of others: Disagreement, agreement, and synergy. Philosophers’ Imprint. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/phimp/3521354.0016.011/--updating-on-the-credences-of-others-disagreement-agreement?view=image.

Flache, A., Mäs, M., Feliciani, T., Chattoe-Brown, E., Deffuant, G., Huet, S., et al. (2017). Models of social influence: Towards the next frontiers. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/20/4/2.html.

Forrest, P. (1985). The Lehrer/Wagner theory of consensus and the zero weight problem. Synthese, 62, 75–78.

Gigerenzer, G. (2007). Gut feelings: The intelligence of the unconscious. New York: Penguin.

Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Rationality for mortals. New York: Oxford University Press.

Goldman, A. (1986). Epistemology and cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Golub, B., & Jackson, M. (2010). Naï ve learning in socia networks and the wisdom of crowds. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2, 112–149.

Govan, C. L., & Williams, K. D. (2004). Changing the affective valence of the stimulus items influences the IAT by re-defining the category labels. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 357–365.

Griffiths, T. L., Kemp, C., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2008). Bayesian models of cognition. In R. Sun (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of computational psychology (pp. 59–100). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Hegselmann, R., & Krause, U. (2002). Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence models, analysis, and simulation. Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/5/3/2.html.

Higgins, E. T., & Rholes, W. S. (1978). Saying is believing: Effects of message modification on memory and liking for the person described. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14, 363–378.

Hodas, N., & Lerman, K. (2014). The simple rules of social contagion. Scientific Reports. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep04343.

Jackson, F. (1982). Epiphenomenal Qualia. The Philosophical Quarterly, 32, 127–136.

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 2). New York: Holt.

Jeffrey, R. (1983). The logic of decision (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jeffrey, R. (1992). Probability and the Art of judgment. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J., & Thaler, R. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and the Status Quo Bias. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 193–206.

Kleinberg, J. (2007). Cascading behavior in networks: Algorithmic and economic issues. In N. Nisan, T. Roughgarden, E. Tardos, & V. Vazirani (Eds.), Algorithmic game theory (pp. 612–632). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lassiter, C., Norasakkunkit, V., Shuman, B., & Toivonen, T. (2018). Diversity and resistance to change: Macro conditions for marginalization in post-industrial societies. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00812/full.

Lehrer, K. (1976). When rational disagreement is impossible. Noûs, 10, 327–332.

Lehrer, K., & Wagner, C. (1981). Rational consensus in science and society a philosophical and mathematical study. Dordrecht: Springer.

Lee, K., Quinn, P., & Pascalis, O. (2017). Face race processing and racial bias in early development: A perceptual-social linkage. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 256–262.

Macrae, C. N., Bodenhausen, G. V., Milne, A. B., & Jetten, J. (1994). Out of mind but back in sight: Stereotypes on the rebound. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 808–817.

Martini, C., Sprenger, J., & Colyvan, M. (2013). Resolving disagreement through mutual respect. Erkenntnis, 78, 881–898.

Maxwell, N. (1968). Understanding sensations. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 46, 127–146.

Maxwell, N. (2003). Three philosophical problems about consciousness and their possible resolution. http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/2238/.

Mendoza, S. A., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Amodio, D. M. (2010). Reducing the expression of implicit stereotypes: Reflexive control through implementation intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 512–523.

Nagel, T. (1974). What is it like to be a bat? The Philosophical Review, 83, 435–450.

Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). The Halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 250–256.

O’Connor, C., & Weatherall, J. (2019). The misinformation age: How false beliefs spread. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Otto, A. R., & Eichstaedt, J. C. (2018). Real-world unexpected outcomes predict city-level mood states and risk-taking behavior. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206923.

Ramsey, F. (1931). In R. B. Braithwaite (Ed.), The foundations of mathematics and other logical essays. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Raz, J. (1999). Engaging reason: On the theory of value and action. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sakoda, J. M. (1971). The checkerboard model of social interaction. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 1, 119–132.

Sartre, J.-P. (2007/1946). Existentialism is a Humanism. Translated by Carol Macomber. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schelling, T. C. (1971). Dynamic models of segregation. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 1, 143–186.

Schopenhauer, A. (2014/1818). The world as will and representation. Edited by Christopher Janaway. Translated by Judith Norman and Alistair Welchman. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Silver, N. (2012). The signal and the noise: Why so many predictions fail-but some don’t. New York: Penguin.

Stephens-Davidowitz, S. (2017). Everybody lies: Big data, new data, and what the internet can tell us about who we really are. New York: HarperCollins.

Talbott, W., Bayesian epistemology. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2016 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/epistemology-bayesian/.

Wedgwood, R. (2009). The normativity of the intentional. In B. McLaughlin, A. Beckermann, & S. Walter (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the philosophy of mind (pp. 421–436). New York: Oxford University Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations. Translated by Elizabeth Anscombe. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1–27.

Zollman, K. (2007). The communication structure of epistemic communities. Philosophy of Science, 74, 574–587.

Zollman, K. (2015). Modeling the social consequences of testimonial norms. Philosophical Studies, 172, 2371–2383.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lassiter, C. Arational belief convergence. Synthese 198, 6329–6350 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02465-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-019-02465-6