Abstract

I develop a reduction of grounding to essence. My approach is to think about the relation between grounding and essence on the model of a certain concept of existential dependence. I extend this concept of existential dependence in a couple of ways and argue that these extensions provide a reduction of grounding to essence if we use sorted variables that range over facts and take it that for a fact to obtain is for it to exist. I then use the account to resolve various issues surrounding the concept of grounding and its connection with essence; apply the account to paradigm cases and to the impure logic of grounding; and respond to objections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The predicate ‘exists’ is understood in a non-quantificational way. Although every existing item is such that there is something identical with it, some items for which there is something identical to them do not exist.

The concept of existential dependence deployed is a hybrid of Lowe and Tahko’s (EDE) and (EDC) (Lowe and Tahko 2015). If both are genuine concepts of dependence then so too is the hybrid of them. I remain neutral on what other forms of dependence there may be. Since I am interested in the connection between grounding and essence, the sorts of dependence I am interested in are broadly essentialist. On the varieties of dependence, see Correia (2008) and Lowe and Tahko (2015).

I am often sloppy over use/mention when there is little risk of confusion. Also, I assume a necessitist framework. For challenges to contingentist essentialism, see Teitel (2017).

We can form plural names using lists of singular names. For example, given that ‘Socrates’, ‘Plato’, and ‘Aristotle’ are singular names, ‘Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle’ is a plural name. I assume that pluralities are non-empty but that there may be a single item belonging to some. We can then say that for every x there are some X such that for any y, y belongs to X if and only if y is identical with x. The predicate ‘belongs to’ is a primitive predicate that takes a singular term and a plural term as arguments. We can form statements such as ‘X belongs to Y’ but they are shorthand for ‘For all x, x belongs to X only if x belongs to Y’.

There are other distinctions of essence, such as the distinction between mediate and immediate essence (Fine 1994a, b). What divides mediate from immediate essence concerns dependence. For example, that it is part of the mediate essence of {Socrates} that Socrates is human but not part of its immediate essence (Fine 1995a). I will assume an immediate conception of essence. This seems somewhat standard when considering the concept of constituive essence (Dasgupta 2016; Glazier 2017).

A few remarks. First, the predicate ‘exists’ is distributive: if X exist then, for every x belonging to X, x exists. Second, although I write definitions in logicese, full formalizations may in addition be helpful. So let us follow standard notation and use an indexed box for the essentialist operator and ‘E’ for the distinguished existence predicate. Then x existentially depends on X iff\(_{df}\)\((\exists R)[\Box _{x} (Ex \rightarrow (RxX \wedge EX))]\). The variable R functions syntactically as a predicate and can be bound by suitable existential quantifiers (Prior 1971).

Since Existential Grounding is a crucial component to the reduction, I will provide a formalization of it: x is existentially grounded in Y iff\(_{df}\)\((\exists R)[(\Box _x (Ex \rightarrow (\exists X)(RxX \wedge EX))) \wedge (RxY \wedge EY)]\). In what follows, I will talk about existential grounding as being factive, although it may seem unclear how Existential Grounding implies the existence of the grounded item. See Sect. 4.2.

It is worth mentioning that we can from Existential Grounding define a partial concept: x is partially existentially grounded in Y iff\(_{df}\) For some X, Y belongs to X and x is existentially grounded in X.

I can only really stipulate that Existential Grounding obeys Non-Circularity (E). For those who think that relations of co-dependence are within the realm of theoretical possibility, see Sect. 3.2 on intergrounding.

Compare with the case of sets. On an immediate conception, {Socrates} and Aristotle are the members of {{Socrates}, Aristotle}. But we can define a mediate concept, where X are members of x if and only if for every y belonging to X, either y is a member of x in the immediate sense, or is a member of a member of x in the immediate sense, etc. On this mediate concept of membership, Socrates, {Socrates}, and Aristotle are the members of {{Socrates}, Aristotle}; and it is also the case that {{Socrates}, Aristotle} and {Socrates, {Socrates}, Aristotle} have the same members, although they are distinct sets.

I do not include in this discussion the concept of dependence invoked in Fine’s logic: that x depends on y if and only if it is essential to x that \(y = y\) (Fine 1995b).

Further investigation will be required to specify exactly which consequences are essential on this conception.

Since Fact Grounding is crucial to articulating the connection between grounding and essence, I provide a full formalization: f is fact grounded in G iff\(_{df}\)\((\exists R)[(\Box _f (Ef \rightarrow (\exists F)(RfF \wedge EF))) \wedge (RfG \wedge EG)]\).

This general strategy for treating determinables can be found in Rosen (2010).

For example, if we take the statement ‘Every natural number has a successor’ and formalize it ‘\((\forall x)[x \epsilon \mathbb {N} \rightarrow (\exists y)(Syx)]\)’ then for any term t ‘\(t \epsilon \mathbb {N} \rightarrow (\exists y)(Syt)\)’ expresses a fact that is an instance of the universal fact. For example, there is the fact that I am a natural number only if I have a successor, which is an instance of the universal. It is grounded in the fact that I am not a natural number. If a universal statement ‘\((\forall x)(Fx \rightarrow Gx)\)’ is vacuoulsy true because nothing is F, then every instance of the universal will be grounded at least in the negation of the antecedent. If a universal statement ‘\((\forall x)[Fx]\)’ is false then some instance Ft, which expresses a fact, is such that the fact it expresses fails to exist and the fact that \(\lnot Ft\) exists. Recall that I am operating within a domain of possible facts and a distinguished predicate for existence that sorts facts into those that obtain and those that do not.

There is a bit of redundancy here: the ascription of existence to F can be dropped, since the predicate ‘\(R_{\exists }\)’ holds only between an existential and its existent instances.

There is a bit of redundancy here: the ascription of existence to F can be dropped, since the predicate ‘\(R_{\vee }\)’ holds only between a disjunctive fact and its existent disjuncts.

Negations can then be dealt with in the way suggested in Fine (2012a, pp. 63–64). But the present suffices to sketch how the account on offer begins to treat the grounds of first-order logic.

We can define a concept of partial grounding given the Essence-Grounding Connection and the definition of partial existential grounding given in connection with Existential Grounding. So f will be partially grounded in G iff for some F, G belongs to F and f is grounded in F. Similarly for the case of Fact Grounding.

This may require introducing some surprising essential truths that involve somewhat contrived predicates, such as ‘are a single true disjunct’, and so on. In any case, I am inclined to take the more general rules that the account provides. For example, that disjunctions are grounded in their true disjuncts together.

Perhaps these are instances of merely partial grounding. For simplicity, we assume that they are cases of full grounding if true.

The predicate ‘are the mass\(\ldots \)’ takes a plural and singular argument.

It is this aspect of the Essence-Grounding Connection—namely, the definition in terms of Existentially Dependent over something with the rigidity of Existential Dependence— that evades objections that Schnieder (2017) raises against other theorists, such as Schaffer (2016), who link grounding and existential dependence.

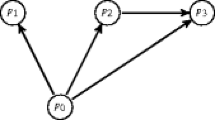

For example, consider the disjunctive fact \(f \vee g\). Suppose that F are its true disjuncts and so \(f \vee g\) is fact grounded in F, where g belongs to F iff \(g = f\). Suppose further that f is not fact grounded in anything and so, for the sake of argument, is a fundamental fact. This does not imply that f is a fundamental item, since f is plausibly existentially grounded in its constituents X. Since ‘X’ is not a sorted variable ranging over pluralities of facts, this is not an instance of fact grounding and so does not disrupt f’s being a fundamental fact, even though it is not a fundamental item. For our purposes here, (i) to be a fundamental item is to not be existentially grounded in anything; and (ii) to be a fundamental fact is to not be fact grounded in anything.

References

Carnino, P. (2015). On the reduction of grounding to essence. Studia Philosophica Estonica, 7(2), 56–71.

Correia, F. (2006). Generic essence, objectual essence, and modality. Nous, 40(4), 753–767.

Correia, F. (2008). Ontological dependence. Philosophy Compass, 3(1013), 1032.

Correia, F. (2012). On the reduction of necessity to essence. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 84(3), 639–653.

Correia, F. (2013). Metaphysical grounds and essence. In M. Hoeltje, B. Schnieder, & A. Steinberg (Eds.), Varieties of dependence, basic philosophical concepts series (pp. 271–96). Mnchen: Philosophia.

Correia, F., & Schnieder, B. (2012). Metaphysical grounding: understanding the structure of reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Correia, F., & Skiles, A. (2017). Grounding, essence, and identity. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research,. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12468.

Dasgupta, S. (2016). Metaphysical rationalism. Nous, 50(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12082.

deRosset, L. (2013). Grounding explanations. Philosophers’ Imprint, 13(7), 1.

deRosset, L. (2014). On weak ground. Review of Symbolic Logic, 7(4), 713–744.

Fine, K. (1994a). Essence and modality. In J. Tomberlin (Ed.), Philosophical perspectives 8: logic and language (pp. 1–16). Atascadero, CA: Ridgeview.

Fine, K. (1994b). Ontological dependence. Proceedings of the aristotelian society, 95, 269–90.

Fine, K. (1995a). Senses of essence. In Walter Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.), Modality, morality, and belief (Vol. 5373). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fine, K. (1995b). The logic of essence. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 24, 241–73.

Fine, K. (2001). The question of realism. Philosophers’ Imprint, 1(1), 1–25.

Fine, K. (Ed.) (2005). Necessity and non-existence’. In Modality and tense. Philosophical papers, Chapter 9 (pp. 321–354). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fine, K. (2012a). A guide to ground. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fine, K. (2012b). The pure logic of ground. Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(1), 1–25.

Fine, K. (2015). Unified foundations for essence and ground. Journal of the American Philosophical Association, 1(2), 296–311.

Glazier, M. (2017). Essentialist explanation. Philosophical Studies, Philosophical Studies, 174, 2871–2889.

Koslicki, K. (2012). Varieties of ontological dependence. In F. Correia & B. Schnieder (Eds.), Metaphysical grounding: Understanding the structure of reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koslicki, K. (2015). The coarse-grainedness of grounding. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 9, 304–344.

Leuenberger, S. (2014). Grounding and necessity. Inquiry, 57, 151–74.

Lowe, E. J., Tahko, T. (2015). Ontological dependence. In Zalta, E. N. (ed.) Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entrie/dependence-ontological/ (2015).

Prior, A. N. (1971). Platonism and quantification. In P. T. Geach, & A. J. P. Kenny (Eds.), Objects of thought (pp. 31–47). Oxford: Oxford, University Press.

Raven, M. (2015). Ground. Philosophy. Compass, 10(5), 322–333.

Rosen, G. (2010). Metaphysical dependence: Grounding and reduction. In R. Hale & A. Hoffman (Eds.), Modality: Metaphysics, logic, and epistemology (pp. 109–136). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rosen, G. (2015). Real definition. Analytic Philosophy, 56(3), 189–209.

Schaffer, J. (2009). On what grounds what. In D. Chalmers, D. Manley, & R. Wasserman (Eds.), Metametaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, J. (2016). Grounding in the image of causation. Philosophical Studies, 173(1), 49–100.

Schnieder, B. (2017). Grounding and dependence. Synthese. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-017-1378-z.

Skiles, A. (2015). Against grounding necessitarianism. Erkenntnis, 80(4), 717–751.

Teitel, T. (2017). Contingent existence and the reduction of modality to essence. Mind,. https://doi.org/10.1093/mind/fzx001.

Thompson, N. (2016). Metaphysical interdependence. In Mark Jago (Ed.), Reality making (pp. 38–56). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williamson, T. (2013). Modal logic as metaphysics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, A. (2017). Metaphysical causation. Nous. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12190.

Wilson, J. (2014). No work for a theory of grounding. Inquiry, 57(5–6), 535579.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Louis deRosset, Kit Fine, Kathrin Koslicki, Donnchadh O’Conaill, Mike Raven, Riin Sirkel, Tuomas Tahko, and to two anonymous referees for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zylstra, J. The essence of grounding. Synthese 196, 5137–5152 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1701-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-018-1701-3