Abstract

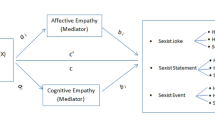

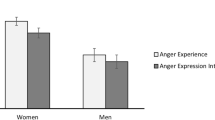

Sexist humor may be more difficult to confront than serious expressions of sexism because humor disguises the biased nature of the remark. The present research investigated whether delivering a sexist remark as a joke, compared to a serious statement, tempered perceptions that the speaker was sexist which, in turn, made women less likely to confront. Using a computer-mediated instant messaging paradigm, women were randomly assigned to receive the same sexist remark phrased either in a serious manner or as a joke. We recorded how women actually responded to the sexist remark and coded for confrontation. In Experiments 1 (195 women) and 2 (134 women) we found that humor decreased perceptions that the speaker was sexist. Furthermore, as perceptions that the perpetrator was sexist decreased, women’s confronting also decreased. Experiment 2 demonstrated an additional consequence of reducing the perceived sexism of the perpetrator—it increased tolerance of sexist behavior perpetrated against an individual woman and sexual harassment more generally. Interestingly, the indirect effects only appeared when women at least moderately endorsed hostile sexism. For hostile sexists, failure to identify sexism reduced confrontation and increased tolerance for sexual harassment and sexist behavior. Contrary to popular belief, humor can actually make sexist messages more dangerous and difficult to confront than serious remarks.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Asburn-Nardo, L., Morris, K. A., & Goodwin, S. A. (2008). The Confronting Prejudiced Responses (CPR) Model: Applying CPR in organizations. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 7(3), 332–342.

Attardo, S. (1993). Violation of conversational maxims and cooperation: The case of jokes. Journal of Pragmatics, 19, 537–558.

Ayres, M. M., Friedman, C. K., & Leaper, C. (2009). Individual and situational factors related to young women’s likelihood of confronting sexism in their everyday lives. Sex Roles, 61, 449–460.

Baird, C. L., Bensko, N. L., Bell, P. A., Viney, W., & Woody, W. D. (1995). Gender influence on perceptions of hostile environment sexual harassment. Psychological Reports, 77, 79–82. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.1.79.

Baron, R. S., Burgess, M. L., & Kao, C. F. (1991). Detecting and labeling prejudice: Do female perpetrators go undetected? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 115–123. doi:10.1177/014616729101700201.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2013). Sexism in contemporary societies: How it is expressed, perceived, confirmed, and resisted. In M. Ryan & N. Branscombe (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of gender and psychology (pp. 288–305). London: Sage Publishers.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2015). Detecting and experiencing prejudice: New answers to old questions. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 139–219.

Bemiller, M. L., & Schneider, R. Z. (2010). It’s not just a joke. Sociological Spectrum, 30, 459–479. doi:10.1080/02732171003641040.

Bill, B., & Naus, P. (1992). The role of humor in the interpretation of sexist incidents. Sex Roles, 27, 645–664. doi:10.1007/BF02651095.

Blanchard, F. A., Crandall, C. S., Brigham, J. C., & Vaughn, L. (1994). Condemning and condoning racism: A social context approach to interracial settings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79(6), 993–997.

Butland, M. J., & Ivy, D. K. (1990). The effects of biological sex and egalitarianism on humor appreciation: Replication and extension. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 5, 353–366.

Crandall, C. S., & Eshleman, A. (2003). A justification-suppression model of the expression and experience of prejudice. Psychological Bulletin, 129(3), 414–446.

Czopp, A. M. (2013). The passive activist: Negative consequences of failing to confront anti-environmental statements. Ecopsychology, 5, 17–23.

Czopp, A. M., & Monteith, M. J. (2003). Confronting prejudice (literally): Reactions to confrontations of racial and gender bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 532–544.

Czopp, A. M., Monteith, M. J., & Mark, A. Y. (2006). Standing up for a change: Reducing bias through interpersonal confrontation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 784–803.

Deaux, K., & Emswiller, T. (1974). Explanations of successful performance on sex-linked tasks: What is skill for the male is luck for the female. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29(1), 80–85.

Devine, P. G., Monteith, M. J., Zuwerink, J. R., & Elliot, A. J. (1991). Prejudice with and without compunction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(6), 817–830.

Dodd, E. H., Giuliano, T. A., Boutell, J. M., & Moran, B. E. (2001). Respected or rejected: Perceptions of women who confront sexist remarks. Sex Roles, 45(7–8), 567–577.

Duncan, W. J., Smeltzer, L. R., & Leap, T. L. (1990). Humor and work: Applications of joking behavior to management. Journal of Management, 16, 255–278. doi:10.1177/014920639001600203.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (1993). Notice of proposed rule making: Guidelines on harassment based on race, color, religion, gender, national origin, age, or disability. Federal Register, 58, 51266–51269.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Swan, S., & Fischer, K. (1995). Why didn’t she just report him? The psychological and legal implications of women’s responses to sexual harassment. Journal of Social Issues, 51, 117–138.

Ford, T. E. (2000). Effects of sexist humor on tolerance of sexist events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(9), 1094–1107.

Ford, T. E., & Ferguson, M. A. (2004). Social consequences of disparagement humor: A prejudiced norm theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(1), 79–94.

Ford, T. E., Boxer, C. F., Armstrong, J., & Edel, J. R. (2008). More than “just a joke”: The prejudice-releasing function of sexist humor. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(2), 159–170.

Ford, T. E., Woodzicka, J. A., Triplett, S. R., & Kochersberger, A. O. (2013). Sexist humor and beliefs that justify societal sexism. Current Research in Social Psychology, 21, 64–81.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512.

Gray, J. A., & Ford, T. E. (2013). The role of context in the interpretation of sexist humor. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 26(2), 277–293.

Greenwald, A. G., & Pettigrew, T. F. (2014). With malice toward none and charity for some. American Psychologist, 69(7), 669–684.

Greenwood, D., & Isbell, L. M. (2002). Ambivalent sexism and the dumb blonde: Men’s and women’s reactions to sexist jokes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 341–50.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Hemmasi, M., Graf, L. A., & Russ, G. S. (1994). Gender related jokes in the workplace: Sexual humor or sexual harassment? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 1114–1128. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1994.tb02376.x.

Henkin, B., & Fish, J. M. (1986). Gender and personality differences in the appreciation of cartoon humor. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 120, 157–175. doi:10.1080/00223980.1986.9712625.

Inman, M. L., & Baron, R. S. (1996). Influence of prototypes on perceptions of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 727–739.

Inman, M. L., Huerta, J., & Oh, S. (1998). Perceiving discrimination: The role of prototypes and norm violation. Social Cognition, 16, 418–450. doi:10.1521/soco.1998.16.4.418.

Johnson, A. M. (1990). The “only joking” defense: Attribution bias or impression management? Psychological Reports, 67, 1051–1056.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498.

Jost, J. T., Banaji, M. R., & Nosek, B. A. (2004). A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology, 25, 881–919.

Kahn, W. A. (1989). Toward a sense of organizational humor: Implications for organizational diagnosis and change. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 25, 45–63.

Klonis, S. C., Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (2005). Internal and external motivation to respond without sexism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1237–1249. doi:10.1177/0146167205275304.

La Fave, L. (1972). Humor judgments as a function of reference groups and identification classes. In J. H. Goldstein & P. E. McGhee (Eds.), The psychology of humor (pp. 195–210). New York: Academic.

La Fave, L., Haddad, J., & Maesen, W. A. (1976/1996). Superiority, enhanced self-esteem, and perceived incongruity humor theory. In A. J. Chapman & H. C. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 63–91). New York, NY: Wiley.

LaFrance, M., & Woodzicka, J. A. (1998). No laughing matter: Women’s verbal and nonverbal reactions to sexist humor. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target’s perspective (pp. 61–80). San Diego: Academic.

Lerner, M. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York: Plenum.

Mallett, R. K., & Wagner, D. E. (2011). The unexpectedly positive consequences of confronting sexism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(1), 215–220.

Mazer, D. B., & Percival, E. (1989). Ideology or experience? Sex Roles, 20, 135–145.

Monteith, M. J., Devine, P. G., & Zuwerink, J. R. (1993). Self-directed versus other-directed affect as a consequence of prejudice-related discrepancies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 198–210.

Moore, T. E., Griffiths, K., & Payne, B. (1987). Gender, attitudes towards women, and the appreciation of sexist humor. Sex Roles, 16(9/10), 521–531. doi:10.1007/BF00292486.

Napier, J. L., Thorisdottir, H., & Jost, J. T. (2010). The joy of sexism? A multinational investigation of hostile and benevolent justifications for gender inequality and their relations to subjective well-being. Sex Roles, 62, 405–419.

Perry, E. L., Kulik, C. T., & Schmidtke, J. M. (1997). Blowing the whistle: Determinants of responses to sexual harassment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 19, 457–482.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments and Computers, 36, 717–731.

Pryor, J. B. (1995). The psychosocial impact of sexual harassment on women in the U.S. Military. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 581–603.

Ryan, K., & Kanjorski, J. (1998). The enjoyment of sexist humor, rape attitudes, and relationship aggression in college students. Sex Roles, 38, 743–756.

Shelton, J. N., Richeson, J. A., Salvatore, J., & Hill, D. M. (2006). Silence is not golden: Intrapersonal consequences of not confronting prejudice. In S. Levin & C. Van Laar (Eds.), Social stigma and group inequality: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 65–81). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Sue, D. W. (2010). Micro-aggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken: Wiley.

Swim, J. K., & Hyers, L. L. (1999). Excuse me—what did you just say?! Women’s public and private reactions to sexist remarks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 68–88.

Swim, J. K., Cohen, L. L., & Hyers, L. L. (1998). Experiencing everyday prejudice and discrimination. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target’s perspective (pp. 37–60). San Diego: Academic.

Swim, J. K., Mallett, R. K., Russo-Devosa, Y., & Stangor, C. (2005). Judgments of sexism: A comparison of the subtlety of sexism measures and sources of variability in judgments of sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 406–411.

Thomae, M., & Viki, G. T. (2013). Why did the woman cross the road? The effect of sexist humor on men’s rape proclivity. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 7, 250–269.

Thomas, C. A., & Esses, V. M. (2004). Individual differences in reactions to sexist humor. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 7, 89–100. doi:10.1177/1368430204039975.

Tougas, F., Brown, R., Beaton, A. M., & Joly, S. (1995). Neosexism: Plus Ca change, plus C’est pareil. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 842–849.

Woodzicka, J. A., & LaFrance, M. (2001). Real versus imagined gender harassment. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 15–30.

Woodzicka, J. A., Mallett, R. K., Hendricks, S., & Pruitt, A. (2015). It’s just a (sexist) joke: Comparing reactions to racist and sexist sentiments. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 28, 289–309.

Zillmann, D. (1983). Disparagement humor. In P. E. McGhee & J. H. Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of Humor Research (pp. 85–107). New York: Springer.

Zillmann, D., & Cantor, J. R. (1972). Directionality of transitory dominance as a communication variable affecting humor appreciation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 191–198.

Zillmann, D., & Cantor, J. R. (1976/1996). A disposition theory of humor and mirth. In A. J. Chapman & H. C. Foot (Eds.), Humor and laughter: Theory, research and applications (pp. 93–116). New York, NY: Wiley & Sons.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mallett, R.K., Ford, T.E. & Woodzicka, J.A. What Did He Mean by that? Humor Decreases Attributions of Sexism and Confrontation of Sexist Jokes. Sex Roles 75, 272–284 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0605-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0605-2