Abstract

Prior studies document that SG&A expenditure (exclusive of R&D and advertising expenditure) creates an intangible asset value despite that U.S. GAAP requires SG&A to be expensed immediately as a period cost. In this paper, we investigate whether the credit default swap (CDS) market recognizes the intangible asset value of SG&A expenditure. Our findings show that although the CDS market views contemporaneous SG&A expenditure as a risk factor on average, it does recognize the intangible asset value created by SG&A. Specifically, the positive association between CDS spread and SG&A expenditure is weaker for firms with higher SG&A intangible asset value. This suggests that SG&A’s intangible asset value helps mitigate credit risk. We also document that such mitigation effect is stronger when the accounting information of the reference entity is more transparent and when the reference entity is more financially constrained. Our inferences remain when we: (1) examine the short window CDS market reaction to SG&A information around SEC filing dates, and (2) use total SG&A expenditure including R&D and advertising in our analysis. Overall, this study shows that the credit market differentiates between the expense and the asset components of SG&A expenditure and lowers the risk assessment of firms with higher intangible asset values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Firms report SG&A expenditure in income statement as the sum of all direct expenses and indirect expenses not related to the production of any goods or service. Specifically, selling expenditure includes the cost of marketing, distributing products and providing product-related services. General and administrative expenditure includes the costs of managing and developing the business (Banker et al. 2019). Banker et al. (2019) show that the SG&A expenditure on average accounts for 37 percent of a company’s total assets, compared to 4 percent for R&D expenditure in their sample.

To clarify, SG&A expenditure and R&D/ advertising expense are very different in at least the following two respects. Firstly, SG&A expenditures are more commonly reported than R&D/advertising across all industries, and the magnitude is usually greater (Banker et al. 2019). More importantly, the intangibles commingled in SG&A significantly exceed R&D and advertising (Enache and Srivastava 2018). Prior research on the value of intangible assets has mainly focused on research and development (R&D) and advertising expenditures (Woolridge 1988; Chan, Martin, and Kensinger 1990; Lev and Sougiannis 1996; Chan, Lakonishok, and Sougiannis 2001; Eberhart, Maxwell, and Siddique 2004), and they provide scant details on its constituent items other than R&D and advertising (Enache and Srivastava 2018). Given that SG&A expenditure creates future benefits, the accounting treatment for SG&A, especially the portion excluding R&D and advertising, may lead to investors’ under-valuation of SG&A (Banker et al. 2019). Secondly, the future benefits created by SG&A are more certain (i.e., less risky) than that of R&D (Enache and Srivastava 2018). Compared to equity market investors, debt market investors are more risk averse and care more about the downside risk (Myers 1977, Acharya et al. 2011). Therefore, given different characteristics of SG&A and R&D/advertising expense, CDS market may price them differently. We would like to thank our referee for bring this to our attention.

For instance, marketing activities such as brand developing, customer relationship maintaining, and management group training create future value in different ways, depending on firms’ nature (Leone and Schultz 1980; Cleland and Bruno 1996; Hauser et al. 1994; Ittner and Larcker 1998; Banker et al. 2000; Brynjolfsson and Hitt 2000).

Unlike standard structural models (Merton 1974) and reduced-form models (Das 1995; Das and Sundaram 2000; Hull and White 2000a, 2000b), the DL model relaxes the assumption that the asset value and asset structure of reference entities are all observable to credit market investors when they explore the role of financial reports in the credit market pricing process. In their model, investors receive noisy accounting reports about firms’ asset dynamics and asset values, reflecting imperfect information about the bankruptcy risk of reference entities.

In the DL model, the price of a CDS contract is a function of the firm’s assets and leverage. However, the asset value and asset dynamics reflected by periodic financial statements may contain noise. Therefore, the CDS market will also consider other information that is related to firm’s overall bankruptcy risk in the pricing process. For example, Callen et al. (2009) find that the CDS market offers a discount on CDS contracting price when earnings are favorable and demands a higher CDS premium when earnings are unfavorable. The CDS market may have a better estimate on the intrinsic asset value of the company when the company has a better information environment.

The earliest paper discussing CDS contracting price is Merton (1974). In that paper, the author proposes a structural model and relates CDS price to firm’s asset value and capital structure. However, strong assumptions are imposed by the structural model. First, the assets of the reference entity are completely observable. Second, the asset structure of the reference entity behaves according to a known stochastic process. These two assumptions are not likely to be satisfied in the real world. The reduced form model proposed at late 1990s tries to fix the caveat of the structural model, but it does not do a good job. Specifically, the reduced form model releases the full asset revelation assumption of the structural model, but it imposes another assumption that the uncertainty on firm’s asset valuation only comes from exogenous factors. The assumption of the reduced form model counters the fact that the uncertainly on assets could be endogenously determined to a large extent in reality. Therefore, the DL model is considered as more advanced in explaining the reality compared to previous two models, and widely used as a basic theoretical framework in academic research.

Quite a few follow-up empirical studies start to test the implications of DL model and show evidences on the role of accounting signals not reflected in the balance sheet in CDS pricing. For example, a stream of studies examines income statement items and document a negative association between CDS premium and earnings (Callen et al. 2009). Their explanation is that higher earnings indicate higher profitability and thereby lower probability of default in the future (Benkert 2004, Batta 2006, Callen et al. 2009, Das et al. 2009).

A twenty percent straight-line amortization rate is commonly used to estimate the contribution of R&D to firm value every year, so we include four lags of R&D expenditure (deflated by total assets) (Griliches 1979; Chan et al. 2001; Hall et al. 1988). Prior literature has documented that the benefits entailed by advertising investments are usually reflected in firm value soon through its impact on sales in the near future, so we include one lag of advertising expenditure in the estimation model (deflated by total assets) (Pale 1970; Banker et al. 2011; 2019).

The simultaneous problem arises in our estimation model when a firm-level idiosyncratic shock affects both dependent and independent variables and causes inconsistent estimates of coefficients. For instance, an upgrade on technology may affect a firm’s current earnings, current SG&A spending and the effectiveness of SG&A investment simultaneously. To address the simultaneous problem, we use the average SG&A expenditure (deflated by total assets) of other firms in firm i’s four digit SIC code industry as an instrument of the firm’s SG&A expenditure. Industry-average SG&A expenditure is highly correlated with a firm’s SG&A spending but uncorrelated with firm-level idiosyncratic shocks. This practice follows prior studies (Lev and Sougiannis 1996; Hanlon et al. 2003, Banker et al. 2019), as industry-average SG&A expenditure is highly correlated with a firm’s SG&A spending but uncorrelated with firm-level idiosyncratic shocks. To further clarify, we only use industry average as instrument for SG&A when we estimate SG&A future value (model (1), to construct variable SG&A Future Value), but do not use the instrument for the SG&A in our main test (\(SG\&A/T{A}_{t}\) of model (2)).

We require at least 10 non-missing observations to obtain the firm-specific estimate of SG&A future value.

We eliminate observations with at least one non-missing value on SG&A, R&D and Advertising expenditures in the preceding four years.

We obtain qualitatively similar results when using 8 percent or 12 percent as the discount rate.

We need firms’ industry information to construct the instrumental variable, which is the average SG&A (deflated by total assets) of other firms in the same four-digit SIC code industry.

Because we require non-missing data on all variables (including lagged variables) and at least ten time-series observations in the rolling window to perform the time-series regression, we can only get estimates of SG&A future value from 1995 which is thirteen years after 1982.

For a subsample of firm-quarters with non-negative SG&A Future Value, the mean (median) value of SG&A Future Value is 1.150 (0.169). Our main results are robust to the subsample analysis of non-negative SG&A Future Value.

Untabulated results suggests that our inference stays the same when we partition the sample using different cutoffs of Z-scores.

In untabulated analyses, we further estimate the future value of R&D and advertising expense with the same method and explore their risk mitigation effects respectively. The results show that neither R&D nor advertising future value has a significant risk mitigation effect on CDS market’s pricing, which is consistent with our expectation given the stark differences between SG&A vs. R&D and advertising expense. The estimation strategy of the paper may not fully capture the underlying value of R&D and advertising expense given their high uncertainty. We thank our referee for the suggestion.

References

Abid F, Naifar N (2006) The determinants of credit default swap rates: an explanatory study. Int J Theor Appl Financ 9(01):23-42. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219024906003445

Acharya VV, Amihud Y, Litov L (2011) Creditor rights and corporate risk-taking. J Financ Econ 102(1):150–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.04.001

Altman EI (1968) Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. J Financ 23(4):589–609. https://doi.org/10.2307/2978933

Anderson MC, Banker RD, Janakiraman SN (2003) Are selling, general, and administrative costs “sticky”? J Account Res 41(1):47–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00095

Anderson MC, Banker RD, Huang R, Janakiraman S (2007) Cost behavior and fundamental analysis of SG&A costs. J Account Audit Financ 22(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X0702200103

Aunon-Nerin D, Cossin D, Hricko T, Huang Z (2002) Exploring for the determinants of credit risk in credit default swap transaction data: is fixed-income markets’ information sufficient to evaluate credit risk? Working Paper: SSRN 375563. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.375563

Banker RD, Potter G, Srinivasan D (2000) An empirical investigation of an incentive plan that includes nonfinancial performance measures. Account Rev 75(1):65–92. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2000.75.1.65

Banker RD, Huang R, Natarajan R (2011) Equity incentives and long-term value created by SG&A expenditure. Contemp Account Res 28(3):794–830. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01066.x

Banker RD, Huang R, Natarajan R, Zhao S (2019) Market valuation of intangible asset: evidence on SG&A expenditure. Account Rev 94(6):61–90. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52468

Batta GE (2006) Credit derivatives and financial information. Working Paper, SSRN 931070 https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=931070

Beatty A, Weber J, Yu JJ (2008) Conservatism and debt. J Account Econ 45(2–3):154–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2008.04.005

Benkert C (2004) Explaining credit default swap premia. J Futures Mark 24:71–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/fut.10112

Bhat G, Callen JL, Segal D (2016) Testing the transparency implications of mandatory IFRS adoption: the spread/maturity relation of credit default swaps. Manag Sci 62(12):3472–3493. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2015.2318

Blanco R, Brennan S, Marsh IW (2005) An empirical analysis of the dynamic relation between investment-grade bonds and credit default swaps. J Financ 60(5):2255–2281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00798.x

Boone AL, White JT (2015) The effect of institutional ownership on firm transparency and information production. J Financ Econ 117(3):508–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.05.008

Brynjolfsson E, Hitt LM (2000) Beyond computation: Information technology, organizational transformation and business performance. J Econ Perspect 14(4):23–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.14.4.23

Bushman RM, Piotroski JD, Smith AJ (2004) What determines corporate transparency? J Account Res 42(2):207–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2004.00136.x

Callen JL, Livnat J, Segal D (2009) The impact of earnings on the pricing of credit default swaps. Account Rev 84(5):1363–1394. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2009.84.5.1363

Chan S, Martin J, Kensinger J (1990) Corporate research and development expenditures and share value. J Financ Econ 26(2):255–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(90)90005-K

Chan LK, Lakonishok J, Sougiannis T (2001) The stock market valuation of research and development expenditures. J Financ 56(6):2431–2456. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00411

Chen CX, Lu H, Sougiannis T (2012) The agency problem, corporate governance, and the asymmetrical behavior of selling, general, and administrative costs. Contemp Account Res 29(1):252–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.2011.01094.x

Christensen HB, Nikolaev VV (2012) Capital versus performance covenants in debt contracts. J Account Res 50(1):75–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2011.00432.x

Cleland AS, Bruno AV (1996) The market value process: bridging customer and shareholder value. Jossey-Bass

Collin-Dufresn P, Goldstein RS, Martin JS (2001) The determinants of credit spread changes. J Financ 56(6):2177–2207. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00402

Daniels KN, Jensen MS (2005) The effect of credit ratings on credit default swap spreads and credit spreads. J Fixed Income 15(3):16–33. https://doi.org/10.3905/jfi.2005.60542

Daniel K, Titman S (2006) Market reactions to tangible and intangible information. J Financ 61:1605–1643. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00884.x

Das SR (1995) Credit risk derivatives. J Deriv 2(3):7–23. Working Paper, SSRN 6195. https://ssrn.com/abstract=6195

Das SR, Sundara RK (2000) A discrete-time approach to arbitrage-free pricing of credit derivatives. Manag Sci 46:46–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634907

Das SR, Hanouna P, Sarin A (2009) Accounting-based versus market-based cross-sectional models of CDS spreads. J Bank Financ 33:719–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.11.003

Du W, Gadgil S, Gordy MB, Vega C (2019) Counterparty risk and counterparty choice in the credit default swap market. Working Paper, SSRN 2845567. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2845567.

Duffie D, Lando D (2001) Term structures of credit spreads with incomplete accounting information. Econometrica 69(3):633–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00208

Eberhart A, Maxwell W, Siddique A (2004) An examination of long-term abnormal stock returns and operating performance following R&D increases. J Financ 59(2):623–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00644.x

Eisfeldt AL, Papanikolaou D (2013) Organization capital and the cross-section of expected returns. J Financ 68(4):1365–1406. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12034

Elton EJ, Gruber MJ, Agrawal D, Mann C (2001) Explaining the rate spread on corporate bonds. J Financ 56(1):247–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00324

Enache L, Srivastava A (2018) Should intangible investments be reported separately or commingled with operating expenses? New Evid Manag Sci 64(7):3446–3468. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2769

Ericsson J, Renault O (2006) Liquidity and credit risk. J Financ 61:2219–2250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.01056.x

Ericsson J, Jacobs K, Oviedo R (2009) The determinants of credit default swap premia. The J Financ Quant Anal 44:109–132. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40505917

Forte S, Pena JI (2009) Credit spreads: an empirical analysis on the informational content of stocks, bonds, and CDS. J Bank Financ 33(11):2013–2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.04.015

Frankel R, Seethamraju C, Zach T (2008) GAAP goodwill and debt contracting efficiency: evidence from net-worth covenants. Rev Acc Stud 13(1):87–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-007-9045-0

Griliches Z (1979) Issues in assessing the contribution of research and development to productivity growth. Bell J Econ 10(1):92–116. https://doi.org/10.2307/3003321

Hall BH, Cumminq C, Laderman ES, Mundy J (1988) The R&D master file documentation. Working paper, NBER Technical Working Paper No. 72. https://doi.org/10.3386/t0072.

Hanlon M, Rajgopal S, Shevlin T (2003) Are executive stock options associated with future earnings? J Account Econ 36:3–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2003.10.008

Hauser JR, Simester DI, Wernerfelt B (1994) Customer satisfaction incentives. Mark Sci 13(4):327–350

Hull JC, White A (2000a) Valuing Credit Default Swaps I: No Counterparty Default Risk. Working Paper, SSRN 1295226. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1295226

Hull JC, White A (2000b) Valuing Credit Default Swaps II: Modeling Default Correlations. Working Paper, SSRN 1295225. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1295225

Huson MR, Tian Y, Wiedman CI, Wier HA (2011) Compensation committees’ treatment of earnings components in CEOs’ terminal years. Account Rev 87(1):231–259. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10164

Iqbal A, Rajgopal S, Srivastava A, Zhao R (2022) Value of internally generated intangible capital. Working Paper, SSRN 3917998. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3917998

Ittner CD, Larcker DF (1998) Are nonfinancial measures leading indicators of financial performance? An analysis of customer satisfaction. J Account Res 36:1–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491304

Leone R, Schultz R (1980) A study of marketing generalizations. J Mark 44:10–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/1250029

Lev B, Sougiannis T (1996) The capitalization, amortization, and value-relevance of R&D. J Account Econ 21(1):107–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(95)00410-6

Longstaff FA, Mithal S, Neis E (2005) Corporate yield spreads: default risk or liquidity? New evidence from the credit default swap market. J Financ 60(5):2213–2253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00797.x

Martin X, Roychowdhury S (2015) Do financial market developments influence accounting practices? Credit default swaps and borrowers׳ reporting conservatism. J Account Econ 59(1):80–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.09.006

Merton RC (1974) On the pricing of corporate debt: the risk structure of interest rates. J Financ 29(2):449–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1974.tb03058.x

Myers SC (1977) Determinants of corporate borrowing. J Financ Econ 5(2):147–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(77)90015-0

Norden L, Weber M (2004) Informational efficiency of credit default swap and stock markets: the impact of credit rating announcements. J Bank Financ 28(11):2813–2843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.06.011

Peles Y (1970) Amortization of advertising expenditures in the financial statements. J Account Res. https://doi.org/10.2307/2674719

Regier M, Rouen E (2023) The stock market valuation of human capital creation. J Corp Finan 79:102384

Shivakumar L, Urcan O, Vasvari FP, Zhang L (2011) The debt market relevance of management earnings forecasts: evidence from before and during the credit crisis. Rev Financ Stud 16(3):464-486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-011-9155-6

Srivastava A (2014) Why have measures of earnings quality changed over time? J Account Econ 57(2):196–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.04.001

Stickney P, Brown P, Wahlen J (2004) Financial reporting and statement analysis: a strategic perspective. Thomson/South-Western, New York, NY

Woolridge R (1988) Competitive decline and corporate restructuring: Is a myopic stock market to blame? J Appl Corp Financ 1(1):26–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.1988.tb00155.x

Wyatt A (2005) Accounting recognition of intangible assets: theory and evidence on economic determinants. Account Rev 80(3):967–1003. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2005.80.3.967

Zhu H (2006) An empirical comparison of credit spreads between the bond market and the credit default swap market. J Financ Serv Res 29(3):211–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-006-7626-x

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (72172038, 72241425), Sci-Tech Innovation Foundation of School of Management, Fudan University, and Research Fund of Shanghai Data Exchange Corporation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Variable definitions

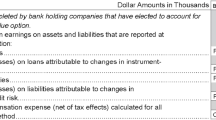

Variable definitions | |

|---|---|

TA | Total assets (Compustat quarterly item ATQ) |

SG&A/TA | Selling, general and administrative expenditure exclusive of R&D and advertising expenditures (Compustat quarterly items XSGAQ—XRDQ—XAD), deflated by total assets |

Total SG&A/TA | Total selling, general and administrative expenditure (Compustat quarterly item XSGAQ), deflated by total assets |

R&D/TA | R&D expenditure (Compustat quarterly item XRDQ), deflated by total assets |

ADV/TA | Advertising expenditure deflated by total assets. Since the quarterly data of advertising expenditure is not available in Compustat, advertising expenditure equals to the annual advertising expense (Compustat annual item XAD) for the last quarter of each fiscal year and equals to 0 for the first three quarters |

OI /TA | Operating income before depreciation, SG&A, R&D, and advertising expenditures (Compustat quarterly items OIBDPQ + XSGAQ), deflated by total assets |

CDS Spread | The spread of 5-year credit default swap, measured in basis points, from Markit |

DEL_CDSSpread | The percentage change of the CDS spread, measured in percentage points |

DEPTH | Number of contributors providing quotes in a CDS trading day from Markit |

MV | Market value (Compustat quarterly items PRCCQ*CSHOQ) |

ROA | Income before extraordinary items, SG&A, R&D, and advertising expenditures (Compustat quarterly items IBQ + XSGAQ), deflated by total assets |

LEV | The sum of short-term and long-term debt (Compustat quarterly items DLTTQ + TLCQ) divided by the sum of total liability (COMPUSTAT quarterly item LTQ) and market value of assets (MV) |

SD_RET | The standard deviation of company’s daily equity returns over the fiscal quarter |

SPOT | The annualized 3-month Treasury-Bill rate from Compustat |

RATING | S&P domestic long-term issuer credit rating from Compustat. The higher is the Rating, the lower the credit rating quality |

Institutional Ownership | The percentage of institutional holdings reported during the quarter. The variable is constructed based on Thomson-Reuters 13F (TR-13F) S34 TYPE3 holding data |

Altman Z-Score | Altman Z-Score is constructed following Altman (1968): \(Altman\,\mathrm{ Z}-\mathrm{Score}=1.2 \times \left(\frac{Net\, working\, capital \left(ACTQ-LCTQ\right)}{Total assets \left(ATQ\right)}\right) +1.4 \times \left(\frac{Retained\, earnings (REQ)}{Total\, assets (ATQ)}\right)+3.3 \times \left(\frac{Earnings\, before\, interest\, and\, taxes(PIQ+XINTQ)}{Total\, assets (ATQ)}\right)+0.6 \times \left(\frac{Market\, value\, of\, equity (MV)}{Book\, value\, of\, liabilities (LTQ)}\right)+1.0\times (\frac{Sales (SALEQ)}{Total\, assets (ATQ)})\) |

Variables measuring value-creating ability of SG&A expenditure | |

SG&A Future Value | The future value-creating ability of SG&A expenditure, which is the sum of discounted coefficients on past SG&A (\(\sum_{k=1}^{3}\frac{{\alpha }_{2,k}}{{\left(1.1\right)}^{k}}\)), estimated from the following model for each firm-year using a rolling window of time-series data (annual data) starting from 1982 \(\begin{aligned} \left( {\frac{{OI}}{{TA}}} \right)_{{i.t}} = & \alpha _{0} + \alpha _{1} \left( {\frac{1}{{TA}}} \right)_{{i,t - k}} + \sum\limits_{{K = 0}}^{3} {\alpha _{{2,k}} } \left( {\frac{{SG\& A}}{{TA}}} \right)_{{i,t - k}} + \sum\limits_{{K = 0}}^{4} {\alpha _{{3,k}} } \left( {\frac{{R\& D}}{{TA}}} \right)_{{i,t - k}} \\ & \quad + \alpha _{4} \left( {\frac{{ADV}}{{TA}}} \right)_{{i,t}} + \varepsilon _{{i,t}} \\ \end{aligned}\) Details of the estimation procedure are provided in Sect. 3 |

Total SG&A Future Value | The future value-creating ability of Total SG&A expenditure, which is the sum of discounted coefficients on past SG&A (\(\sum_{k=1}^{3}\frac{{\alpha }_{2,k}}{{\left(1.1\right)}^{k}}\)) estimated from the following model for each firm-year using a rolling window of time-series data (annual data) starting from 1982 \({\left(\frac{OI}{TA}\right)}_{i.t}= {\alpha }_{0}+{\alpha }_{1}{\left(\frac{1}{TA}\right)}_{i,t-k}+\sum_{K=0}^{3}{\alpha }_{2,k}{\left(\frac{Total SG\&A}{TA}\right)}_{i,t-k} +{\varepsilon }_{i,t}\) Details of the estimation procedure are provided in Sect. 3 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, R., Lin, X. & Xie, Y. Does CDS market price intangible asset value? Evidence from SG&A expenditure. Rev Quant Finan Acc 61, 701–728 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-023-01165-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-023-01165-0