Abstract

This study examines how a large negative economic shock impacts marriage rates for young men in the West Bank. Utilizing data from before and after the sudden and abrupt closure of the Israeli labor market for Palestinian commuters from the West Bank in 2001, our empirical design employs a difference-in-difference strategy and uses the variations in localities’ exposure to the Israeli labor market before the shock. The closure reduced the employment and income of adult men asymmetrically across localities. Our findings show that the closure caused a reduction in marriage rates among young men aged 19 to 29 years, as post-shock changes in marriage rates. Our results suggest that the adverse effect of the economic shock on male marriage is mediated through a combination of rising youth unemployment and rigid expectations about marriage costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This study examines the effect of the closure of the Israeli labor market for Palestinian workers (commuters) on marriage rates among young men in the West Bank of the occupied Palestinian territory (simply “the West Bank” hereafter). This is an important issue, as recent studies have pointed out the role of social norms in mediating and determining the direct impact that economic shocks have on marriage rates (Asadullah & Wahhaj, 2019; Corno et al., 2020; Loughran & Zissimopoulos, 2009; Oppenheimer et al., 1997; Rotz, 2016). More importantly, marriage decisions, particularly at young ages, have profound economic and social implications for society as a whole (Asadullah & Wahhaj, 2019; Field & Ambrus, 2008). An evidence-based understanding of the effect of economic shocks on patterns of male marriage in the context of Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East region, which is characterized by traditional marriage customs, is necessary to shed light on the connections between the economic changes and the social dynamics.

The effect on male marriage of negative aggregate economic shock stemming from the closure is complex in our setting. Commuter jobs are a major source of employment that benefits young male workers (women represent less than one percent of commuters and are therefore not impacted directly by the labor market closure). On the one hand, young unmarried men, who are expected to shoulder the cost of marriage, might be unable to afford the high cost of marriage and might thus decide to postpone the decision to marry. On the other hand, the bride’s father (or other male providers in the family) face the same economic shock and might be even more eager to “marry off” their daughters in order to reduce household expenses. Put differently, faced with a community-wide economic crisis and tight budget constraint, a bride’s family might be willing to accept a lower bride price and less lavish wedding ceremonies in order to hasten marriage and to reduce its household size. The relative strength of these two potential but opposing forces depends on numerous factors, including cultural influences such as religious practices and social norms and expectations. For example, both the groom’s and the bride’s families could be reluctant to change customary practices related to marriage costs, especially the wedding ceremony, which reinforce their social status in their respective communities and publicly show respect to the bride’s family. This makes marriage costs, which at times can be excessive, rigid and stubborn to economic pressures.

We find that marriage rates for men aged 19 to 29 years, defined as the proportion of married men in the specified group age, declined in the West Bank following the abrupt closure of the Israeli labor market in 2001 to Palestinian commuters. Our empirical strategy relies on the variations in locality exposure to the Israeli labor market before the closure, measured by the locality share of male commuters in total male employment, as in (Saad & Fallah, 2020). We use a difference in difference (DiD) strategy to compare marriage rates for young men across localities before and after the shock. We find that the effect of the closure is large and highly significant. One standard deviation increase in locality exposure reduced the marriage rate by 10 percent relative to the mean marriage rate in the base year. Our results are robust to many sensitivity analyses including: dropping localities with high conflict intensity in order to mitigate the concern that our results might be driven by violence; using a binary treatment variable instead of the commuting share; limiting the sample to young men living with their parents in order to address concerns related to internal migration; and controlling for time-varying locality variables.

We argue that rising male unemployment rates in communities affected by the closure led to a decline in marriage. We show that the unemployment rate among young men increased more in hard-hit localities than in less-exposed localities after the shock. That is, localities that had higher exposure to the shock experienced steeper declines in employment rates and suffered a more-severe decline in marriage rates after the outbreak of the Second Intifada. Additionally, we observe male unemployment and marriage rate trends converging across localities after the relaxation of mobility restrictions in 2006.

Our analysis demonstrates the different impacts of the closure across age and education groups, with young (19 to 24 years) and less-educated men being affected most. This heterogeneous impact analysis further strengthens our identification, as the shock had an asymmetrical effect not only across localities but also across age and education groups. Commuters affected by the shock tended to be predominantly young and unskilled, compared to non-commuters, who had a higher age and skills profile. The results of the triple-difference model confirm our heterogeneous effect analysis by comparing male marriage rates within localities across educational groups over time.

It is important to mention that our paper does not directly examine the effect of the closure on marriage decisions for young women in the West Bank. The effect of the closure on marriage for women aged 19 to 29 years might be qualitatively different from its effect on male marriage. The female marriage rate is nearly twice as large as male marriage rates for the age group 19 to 29 years, pointing to a large marriage age gap in the West Bank. The closure mostly affected young and unskilled male workers (commuters are predominately unskilled young men), with marriage trends among older males being highly stable during the investigated period (see Section 3). However, it is not readily clear how female marriage responded to the closure especially in the long run due to the general equilibrium effect and structural shifts in the labor market. To mitigate the effect of the closure, the Palestinian Authority expanded public sector employment, which disproportionately boosted female labor force participation and educational attainment (Fallah et al., 2021). On the other hand, competition from returning male commuters led to lower employment rates among women in specific sectors. While higher female labor force participation resulted in higher employment rates, more economic empowerment, and perhaps lower marriage rates for young women, the competition from returning commuters reverses the trends in women’s employment and marriage. At any rate, examining the long-run effect of the closure on marriage for young women requires a different conceptual framework and a new identification strategy that incorporate both the general equilibrium effects and high marriage migration for women - topics that we leave for future work.

This study adds to the sparse and divergent empirical evidence on the impact of business cycles’ changing economic outcomes on marriage decisions in developed and developing countries owing to the challenge of finding a plausibly exogenous economic shock (Autor et al., 2019; Bishai & Grossbard, 2010; Brandt et al., 2016; Chu et al., 2018, Farzanegan & Gholipour, 2016; Kis-Katos et al., 2018; Krafft & Assaad, 2020; Schaller, 2013; Schneider & Hastings, 2015). It also contributes to the literature investigating the impact of the closure on labor market outcomes (Mansour, 2010; Miaari & Sauer, 2011), child labor, (Di Maio & Nandi, 2013), young people’s educational choices and outcomes (Brück et al., 2019; Di Maio & Nisticó, 2019; Saad & Fallah, 2020), and political outcomes (Miaari et al., 2014). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to highlight the link between working in Israel and marriage among young men in the West Bank.

Previous studies have focused on the role that those social norms play in marriage decisions, including during times of adverse economic shocks. Kearney and Wilson (2018) find that marriage among women increased during the 1970s and 1980s following a positive economic shock but remained unchanged during a similar shock during the 2000s in the United States. The authors relate the opposite responses to economic shocks for cultural reasons, as non-marital births became more acceptable in the 2000s relative to the 1970s. On the other hand, Amin et al. (2017) show that economic incentives such as cash transfer programs might not be able to influence early marriage. In a recent paper, Rexer (2022) studies the impact of male marriage on violence in Nigeria, citing the role of polygamy and pride price.

Our paper is closely related to a recent study by Corno et al. (2020). It demonstrates that marriage decisions correlate differently to negative income shocks in sub-Saharan Africa and India. In explaining these differences, they emphasize the role of the direction of the resource transfer. Corno et al. (2020) argue that, where resource transfers move from the bride’s family to the groom’s (e.g., the dowry practice in India), marriage rates decline in response to a negative shock, as families struggle to afford their daughters’ marriages. By contrast, in sub-Saharan Africa, where payments flow from the groom’s family (bride price) to the bride’s, marriage rates increase, as women’s families are eager to smooth consumption by reducing household size.

Our results seem to differ from those of Corno et al. (2020). While they have shown that marriage rates for women increased in bride-price-paying communities after a negative economic shock, we find the opposite for male marriage rates. Gender and the nature of the shock might partially explain why marriage responded differently across the two studies, as the impact of general negative economic shock on females could be different from mostly male-specific negative economic shock on marriage among men. In addition, the role of social norms is critical but it is more complex and may involve multiple dimensions besides just the direction of the transfer of wealth across spouses at the time of marriage, as postulated in Corno et al. (2020). One possible explanation is that social norms and expectations in the West Bank impose strict rigidity on the costs of marriage, thereby keeping the “price” of marriage out of reach of young men struggling with the adverse economic effects of border closures.Footnote 1 Also, the differences in economic development between the West Bank (a middle-income country) and sub-Saharan Africa (low-income countries) might explain why both communities’ marriage rates will respond differently to shocks.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief background about the Second Intifada and subsequent labor market closure and Section 3 discusses marriage in the West Bank. Section 4 introduces the empirical model, Section 5 describes the datasets, Section 6 discusses the causal mechanisms and event analysis, and Section 7 presents the results. We discuss the results in Section 8. Section 9 concludes.

2 The Second Intifada and Israeli labor market

The West Bank economy has been heavily connected to the Israeli economy since the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in 1967. Faced with hard economic conditions and motivated by the relatively high wages in Israel, thousands of Palestinians commute daily to work in Israel. More than 98 percent of commuters are men and concentrated in low-skilled jobs. Relative to non-commuters, commuters are younger and less educated. At its peak, 40 percent of the labor force in the West Bank was employed in Israel. The number of commuters varied between 1967 and 2000 for political reasons. Nevertheless, Israel continued to employ more than 25 percent of the Palestinian labor force (Angrist, 1995, 1996; Farsakh, 2002; Mansour, 2010; Ruppert Blumer, 2003).

The peaceful demonstrations by Palestinians against the visit of the then-prime minister of Israel, Ariel Sharon, to the Al-Aqsa Mosque in September 2000 escalated quickly to become a widespread uprising against Israeli occupation (Second Intifada).Footnote 2 The Second Intifada became one of the most violent episodes of the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine. Around 4000 Palestinians and 1000 Israelis were killed and many thousands were injured between 2001 and 2006.

Shortly after the outbreak of the Second Intifada, Israel adopted a series of measures to prevent Palestinians from working in Israel and severely limited mobility within the West Bank. As a result, the share of Palestinian workers in Israel of total employment fell from around 25 percent in 1999 to less than 10 percent by 2002.Footnote 3 The consequences of Israeli measures (e.g., mobility restrictions, direct attacks on Palestinian establishments, and trade disruption) on the Palestinian economy were severe, leading to unprecedented unemployment levels (above 25 percent; see Fig. 1) and a double-digit economic decline (10 to 15 percent). Remarkably, the economy started to slowly recover in 2003, registering positive economic growth and improved unemployment numbers, for several reasons. First, the level of violence significantly declined after 2002. Second, Palestinian emigrants’ remittances and international aid substantially increased during the Second Intifada, which might have mitigated its effect on the economy (Saad, 2015). Most aspects of life in the West Bank were disrupted by the Second Intifada to varying degrees, but the public sector, education and health systems, and social activities and social fabric remained highly functional. Nevertheless, the closure and subsequent long-term policies adopted by Israel to reduce the dependency of the Israeli labor market on Palestinian workers profoundly changed the dynamics between the Israeli and Palestinian labor markets, and the share of commuters remained significantly low after the end of the Second Intifada in 2006 (Saad & Fallah, 2020).

The adverse impact of the closure on the labor market was not uniform across the West Bank, with unskilled male workers being affected most (Brück et al., 2019; Mansour, 2010; Saad & Fallah, 2020). Important to our identification, the exposure of West Bank localities to Israel, measured by the locality share of commuters in total male employment, varied significantly before the closure, with a mean of 0.28 and standard deviation of 0.18 percentage points in 1999 (Table 2). Figure 2 shows the geographical distribution of commuters in 1999 (two years before the closure). Overall, the localities near the border with Israel tend to have a higher share of commuters than otherwise relatively similar localities.

3 Marriage in the West Bank

Marriage remains, as in most societies in the region, the cornerstone of society and the most important - if not the sole - vehicle for socially sanctioned sexual relationships. It is a major marker of adulthood and a source of social status for young women and men alike (Singerman, 2008). As Singerman (2008) describes it, there is a “marriage imperative” for all young adults who want to establish a union with their sexual partners. Nonetheless, this imperative is governed by social and economic factors that largely determine the conditions under which it can happen.

These social and economic shifts in Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East often place opposing pressures on the marriage institution and its customs. For example, rising female education across the region might have contributed to a rise in the marriage age and a reduction in underage marriages, whereas persistently low female labor force participation, coupled with adverse unemployment rate gaps, have left women with no option for independence and social mobility but marriage (National Health Marriage Resources Center, 2017). Moreover, rising youth unemployment has placed pressure on young men’s ability to afford the customary costs of marriage borne by the groom. These pressures are further emphasized by rising inequality, which has caused many families to be more dependent on the “bride price” as a mechanism for social matching and the preservation of social status (Anderson, 2007; Kressel et al., 1977). These rising trends in the region, with their opposing effects on marriage rates, are coupled with a rising proportion of young people within the general population, a proportion that is expected to increase even more in the next 10 years. Rashad et al. (2005) point out that the share of people aged 20 to 29 years in the region is expected to increase by 20 percent by 2025, with rises of 65 and 85 percent in Iraq and Yemen, respectively.Footnote 4

Many of the traditions governing marriage in the West Bank are similar across the region. Marriage is a familial affair, as family members play the central role in decisions. Therefore, to fully understand the marriage trends among men in the West Bank, it is necessary to go beyond the standard theory of marriage regarding spouses’ specialization mechanism and the economic value of marriage postulated by early theories of marriage (Becker, 1973; Wilson, 1987). Culture, religion and economic concerns are among the main determinants of the motivation for men to marry in the Middle East.Footnote 5

Indeed, in many cases, marriages are “arranged,” as a result of which partners are acquainted only after a formal marriage proposal is made by the male to the prospective bride’s family. Marriages usually happen between families with preexisting strong communal and blood ties. More than 40 percent of marriages are between relatives in the same extended family (PCBS, 2013). The marriage costs borne by the groom are significant relative to his own and his family’s income. Following traditions and customs, the wedding celebration might last for a few days. The groom is also asked to pay Mukadem, an advanced payment (e.g., cash or gold) made by him to the bride or her family) (Granqvist, 1934, 1935; Warner, 1937).Footnote 6

In recent decades, the institution of marriage in the West Bank has experienced many of the socioeconomic trends that have influenced the rest of the region. Average marriage ages among men and women are rising, driven by declining rates of underage marriage (PCBS, 2018; Johnson, 2010). Even with the influence of the ongoing occupation and conflict on social pressures to propagate, marriage trends in the West Bank, like in other countries in the region, are falling for young adults due to worsening economic conditions and staggering wedding costs (Jarallah, 2008; Rashad et al., 2005).Footnote 7 Nonetheless, the marriage rates among older adults, both women and men, in the West Bank remain high and stable as demonstrated in Table 1. Two reasons might explain this. First, the negative shock in the West Bank was relatively short-lived, mainly affecting young uneducated adults. Second, the unique political context of the West Bank influences the marriage market markedly. High marriage and fertility rates are often perceived as a form of resistance to Israeli occupation (Jad, 2009; Johnson, 2010).

Although there have been impressive improvements in education indicators for women, labor market restrictions remain stringent. In 2018, women still only represented 20 percent of the labor force and half of those women were unemployed (PCBS, 2018). Further, labor force participation for married women ranges from 10 percent in 2001 to 17 percent in 2012 (PCBS, 2013). Consequently, the marriage age for women in Palestine is much lower than that for men. For instance, in 2010, the marriage rate for females between 15 and 19 years was around 8 percent, compared with almost zero for similarly aged males. For 20- to 24-year-olds, the marriage rate is more than 40 percent for women, compared with 10 percent for men.

This divergence between rising trends in education and stagnating labor market outcomes for women does not just reinforce the “marriage imperative,” but it also maintains the traditional centrality of the groom’s income in the success of future marriages. And, indeed, with soaring unemployment in the West Bank and the region as a whole (Amin & Al-Bassusi, 2004; Assaad et al., 2010), we are seeing delayed marriages across the Middle East, as men take more time to save money to meet the costs of marriage (Assaad et al., 2010; Singerman, 2008). In the West Bank, a sharp decline was observed in the three years following the Second Intifada (see Table 1), coinciding with the Israeli labor market closure, as commuting workers, mostly young men, stopped commuting across the border to pursue better-paid jobs.

This study aims to untangle and identify the effect of a large politically induced negative labor market shock on marriage among men by using data from the West Bank before and after the Second Intifada. The ubiquity and uniqueness of the case of the Israeli labor market closure to commuters from the West Bank give us a rare chance to identify the causal linkages between economic shocks and marriage for men in a Muslim-majority Middle Eastern society governed by a bride price custom of the transfer of wealth at marriage.

4 Econometric model

We assess the causal impact of the closure on men marriage in the West Bank by fitting the following DiD linear probability model:

The outcome variable, Yilst, takes the value of one if individual i (a male between 19 and 29 years) from locality l and district s in year t is married (or engaged) and zero if never married. The dummy variable T takes the value of one for the post-treatment years (i.e., 2001 to 2006) and zero for the pre-shock years (1999 to 2000). The share of commuters in 1999 of the total labor force in locality l, Sh1999l, captures the strength of the treatment. The DiD coefficient, β, compares male marriage rates across treated localities with a high and low commuting share in 1999 before and after the Second Intifada. We add locality-fixed effects and year dummies, λl and Tt, to control for time-invariant locality-unobserved characteristics and yearly shocks common to all localities. We include district-by-year fixed effects, γst, to control for time-varying shocks specific to the localities within a district. The locality characteristics in the base year (see Table 2) and individual/household characteristics are gathered in the vectors X1999 and W. If the treatment at the locality level is as good as random, controlling for W will only improve the precision of the estimate of β without changing its magnitude. We interact X1999 with T to control for the small differences in locality-observable variables in the base year. The stochastic disturbance, ϵilst, is clustered at the locality level.

A crucial identifying assumption in our DiD model is that the trajectories of male marriage trends across localities would have followed a similar path if the closure had never occurred. Testing directly for this assumption is unfeasible, as we cannot observe post-counterfactual marriage trends (i.e., marriage rates in treated localities absent the shock after the Second Intifada). Instead, we estimate a dynamic DiD version of Eq. (1) to test for the pre-existing trends in male marriage rates:

The dynamic DiD model compares the year-by-year change in male marriage rates between treated and control localities. The coefficient of the base year − m is normalized to zero; hence, the coefficients of the interaction terms corresponding to the pre-shock years, βk for k = {−(m − 1), −1}, compare the marriage trends across localities before the shock. To show that localities followed similar male marriage trends before the shock, it is necessary to have the pre-shock coefficients k = {−(m − 1), −1} statistically not different from zero.

4.1 Threats to the identification

If married individuals move from treated localities to control localities, our estimates will be spurious, as they will capture the internal mobility effect rather than the economic shock effect on marriage. While we cannot rule out internal migration, evidence from previous studies strongly suggests limited internal mobility within the West Bank during the Second Intifada among young men (Abrahams, 2018; Mansour, 2010; Saad & Fallah, 2020; Zimring, 2019). As an additional check, we show that our results hold when we estimate the model for young men living with their parents. It is extremely unlikely that the decision to migrate for the entire household (or household head) is correlated with the marriage decision for one of the members (excluding the household head) of the household.Footnote 8

Our results would be biased if the strength of the mobility restrictions implemented at the outset of the Second Intifada were correlated with the pre-Intifada commuting share at the locality level. This scenario can be easily ruled out, as the closure was uniformly applied to all localities in the West Bank. Nonetheless, to isolate the impact of the initial closure from the variations in closure policy in the following years (potentially at the locality level), we show that the estimates are robust to adding locality time-varying variables including the commuting share and locality linear trend.

One additional issue remains. If the share of commuters in 1999 was correlated with the locality-unobserved time-varying covariates, our results could be biased. We argue against this scenario for four main reasons. First, localities seem to be similar before the shock, indicating that untreated localities are a good counterfactual for treated localities had the closure not happened. Second, the DiD restricts the conditions under which unobservable variables bias the results. If the effect of an unobservable time-varying covariate on male marriage is unaffected by the shock, then omitting it does not bias the results. Third, the observable time-varying variables in 1999 seem to be statistically uncorrelated with the share of commuters in 1999 in a simple linear regression (results not reported), suggesting that, conditional on the locality-fixed effects, the locality share of commuters is as good as random. On this point, Saad and Fallah (2020) show that the geographical distribution of commuters is largely explained by non-time-varying factors, in particular the distance from Israeli borders and networks. Finally, we employ a triple difference model to control for the locality-unobserved time-varying variables and further limit the way those variables might bias the results.

Finally, we provide evidence that violence does not contaminate our estimates. Specifically, if the commuting share is correlated with the violence intensity following the outbreak of the Second Intifada and violence is negatively correlated with male marriage, attributing the impact of the closure on marriage to the decline in jobs and negative economic shock might be misleading. We tackle this issue by controlling for violence intensity directly or by dropping from the sample localities subject to a high level of violence related to the Second Intifada.Footnote 9

5 Data

The Palestinian Labor Force Survey (PLFS) is a rich micro-level dataset that has been collected quarterly by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) since 1995. The PLFS draws on a nationally representative and random sample of approximately 7600 households in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.Footnote 10 The data provide information about individual characteristics such as employment, wage, education, marital status, and place of work and residence by district and locality, occupation, sex, and household characteristics. Many studies published in high-quality journals rely on the PLFS (Amodio & Di Maio, 2018; Amodio et al., 2021; Di Maio & Nisticó, 2019; Mansour, 2010; Miaari & Sauer, 2011). However, one of its limitations is that the place of work and residence by locality is only available starting from 1999. Hence, we dropped the years before 1999 from the main econometric analysis.

The boundaries of the West Bank with Israel follow the armistice line (Green Line) and Jordan River to the east, with a total area of 5660 sq. km (see Fig. 2). There are around 600 localities in the West Bank, distributed across 10 districts (PCBS census, 1997). Because many localities are small (population of less than 500) and are not necessarily sampled every year in the PLFS, we end up with 165 localities in 1999, comprising more than 85 percent of the population of the West Bank. Of the 165 localities in 1999, only the largest 95 localities show in each year of the PLFS. We estimate the impact of the closure on male marriage using a balanced panel sample (95 localities). Nonetheless, we check the robustness of our results and report the estimates for the unbalanced panel dataset using the 165 localities.

We use the PLFS probability weights to calculate locality-by-year aggregate variables. Table 2 reports the summary statistics of the main locality-level variables in the base year of 1999. Importantly, the table shows that localities with different levels of exposure to the Israeli labor market were relatively similar in 1999. This adds extra credibility to the research design and identification strategy. Nevertheless, we control for many locality-level variables in 1999 in the main econometric specification to rule out that minor differences in localities’ characteristics before the shock might be driving the results.

A supplementary dataset on the intensity of violence, measured by the number of fatalities related to the conflict, since 2000 by locality and year, comes from B’TSELEM, an Israeli NGO.

6 Event analysis and causal mechanisms

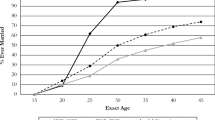

Figure 3 shows the point estimates of the coefficients from the event regression in Eq. (2). It is evident that the assumption of common pre-closure trends in male marriage across localities is strongly supported by the data. The coefficient for 2000, which compares the change in marriage rates from 1999 to 2000 between treated and control localities, is almost zero and statistically insignificant. Importantly, the trends in marriage across localities started to diverge only after the closure in 2001. An extension of the event regression to cover the seven years after the Second Intifada (1999–2012) strengthens our findings further. A check of whether marriage trends began to reconverge after the shock had faded (post-2006) provides additional evidence of similar marriage trends across localities absent the shock, improving our identification strategy.Footnote 11

The impact of the closure on men marriage. The graph plots the coefficients from the generalized DiD regression variables interacted with the share of commuters in 1999. The regression controls for the locality and district-by-year dummies, locality baseline characteristics in 1999 interacted with the corresponding year's dummy, and individual characteristics. The vertical dashed lines represent the 90 percent confidence interval of each of the estimates. The coefficient of the interaction of S1999 and year 1999 dummy is normalized to zero to identify the model. The solid vertical line separates the pre- and post-shock coefficients. The probability weights provided by the PCBS are used in the regression

While there is no formal end date of the Second Intifada, the intensity of conflict and violence dropped significantly from 2006 onward. Israel began slowly loosening security measures, granting more work permits for Palestinians and easing the mobility measures designed to restrict their movement both within the West Bank and between the West Bank and Israel. The number of male workers in Israel started to rise but remained below the pre-Intifada levels. The validity of our test of post-2006 trends depends mainly on the substantially improved mobility within the West Bank after 2006. The relatively easy mobility of workers and goods contributed to equalizing the labor market and economic outcomes across localities. If the closure affects male marriages in the West Bank by changing labor market outcomes, the different trends in marriage across localities will start to converge as labor markets become more integrated.

6.1 Causal mechanism: labor markets and marriage

Labor market closures will directly impact employment, leading to a rise in unemployment and a decline in households’ incomes, with localities most dependent on commuter jobs being the hardest hit. Given the prevalent customs with marriage expenses that place a substantial financial burden on grooms, a negative economic shock reduces grooms’ ability to afford marriage, leading to lower marriage rates in the West Bank. If declining employment and income are the key mechanism through which economic shocks impact marriage rates, the Second Intifada must have had different adverse impacts on local labor markets, with exposed localities being hit hard by the shock during the Second Intifada. The different effects of the closure are expected to fade after 2006, as the internal mobility restrictions imposed during the Second Intifada weakened and local markets became more integrated.

To test for the impact of the closure on local labor markets, we run the event regression in Eq. (2) with the outcome being one if individual i is unemployed and zero if employed. Figure 4 plots the corresponding coefficients for 2000 to 2012. Localities seem to follow similar unemployment trajectories before the Second Intifada and after 2006. Indeed, the unemployment trend for treated localities declines slightly in 2000. The point estimates of the impact of the closure in the period 2001–2005 are large, positive, and precise, indicating a larger increase in unemployment rates in treated than in control localities after the shock.

The impact of the closure on men unemployment. The graph plots the coefficients from the generalized DiD regression variables interacted with the share of commuters in 1999. The regression controls for the locality and district-by-year dummies, locality baseline characteristics in 1999 interacted with the corresponding year's dummy, and individual characteristics. The vertical dashed lines represent the 90 percent confidence interval of each of the estimates. The coefficient of the interaction of S1999 and year 1999 dummy is normalized to zero to identify the model. The solid vertical line separates the pre- and post-shock coefficients. The probability weights provided by the PCBS are used in the regression

Figure 3 shows that male marriage trends are almost a mirror image of male unemployment trends across the West Bank. Before the Second Intifada, marriage and unemployment trajectories follow similar trends across localities Figs. 3 and 4; labor market outcomes and marriage rates start to diverge from 2001, with treated localities facing higher unemployment rates and lower marriage rates. As labor market outcomes begin to converge after 2006, the different impacts of the closure on marriage start to wane, eventually reverting to the pre-Intifada trends in 2012. Showing that the marriage rates across localities that followed similar trends before and after the shock have attenuated is important evidence supporting equal marriage trends in the absence of the shock. In addition, Figs. 4 and 3 suggest that changes in labor markets are a strong potential causal mechanism linking the closure to male marriage in the West Bank.

7 Results

Table 3 reports the estimates of the effects of the closure on marriage for men aged 19 to 29 years. In the first three columns, we restrict the sample to the balanced panel at the locality level. In column (1), we control for the locality, year, and district-by-year fixed effects. Column (2) adds the locality baseline characteristics interacted with T and column (3) estimates the full model, as in Eq. (1). In our preferred model (column (3)), the effect of the closure on male marriage is negative and precisely estimated (p value < 0.0001). As shown in column (3), a one standard deviation increase in the commuting share in 1999 results in a fall in the probability of marriage for young men by 3.9 percentage points. This is approximately a 10 percent decline in the proportion of married young men in 1999 (0.39). The magnitude of this decline in marriage is in line with the estimates of (Autor et al., 2019), who find a 12 percent increase in the proportion of never-married women in the United States in response to a one-unit shock to male employment induced by import competition from China.

Remarkably, the estimates are almost identical across the first three columns. This is an important validation of the empirical design used in this study. To fix the ideas, adding the locality baseline characteristics does not change the results of the basic model, indicating great similarity between localities and/or a low correlation between localities’ commuting shares and the small differences in observable variables. Coupled with common pre-trends, the nearly identical estimates across specifications lend more credibility to the identification strategy. Adding the individual characteristics in column (3) increases the precision of the estimates (lower standard deviation of β) but has almost no effect on their magnitude, further supporting the random treatment assignment measured by the share of commuters before the shock.

Our estimates are robust, albeit smaller and less precise (p value = 0.048), to adding the locality linear trend, which rules out that our results are driven by marriage pre-trends and locality unobservable linear time-varying variables. The coefficients estimated using the unbalanced panel dataset are shown in columns (5) and (6). The results are similar to those in columns (3) and (4). Further, in columns (7) and (8), we restrict the sample to young men living with their parents (or not a household head) and re-estimate Eq. (1) for the balanced and unbalanced panel samples.Footnote 12 While our sample size is significantly reduced, the impact of the closure on marriage is still large and highly statistically significant for the balanced sample (p value = 0.004) and the unbalanced sample (p value = 0.04). Limiting the sample to young men living with their parents thus mitigates the concern that the impact of the closure is driven by internal migration, as the decision to relocate by a household head is highly unlikely to be correlated with his/her son’s marriage decision.

As shown in column (1) of Table 4, the effect of the closure on marriage for young men is relatively unchanged once we control for the locality time-varying variables including the unemployment rate, share of commuters, total population, and number of Palestinian fatalities related to the Second Intifada as a measure of conflict intensity. In columns (2) and (3) of the same table, we drop localities in the 90th and 75th percentiles of conflict intensity, measured by the number of fatalities per 100 people. The results are precise and slightly larger than those of the full balanced sample. Finally, in column (4), we separate the early effect of the closure on marriage from the late effect. We then interact the share of commuters using a dummy variable that takes one for 2004–2006 and zero otherwise and include the new term in the main model. The coefficient of this new interacted term is almost zero, leading to the conclusion that most of the effect happened in the first three years following the shock, which further supports our empirical design and story. The analysis in Table 4 therefore alleviates the concern that violence might conflate the estimate of the effect of the closure on marriage. In addition, controlling for the locality-observed time-varying variables, although demanding empirically, strengthens our identification, as it rules out the effects of post-shock changes in economic conditions and, importantly, changes in mobility measures and the share of commuters that might be correlated with the pre-shock shares.

Next, we separately estimate Eq. (1) for men aged 19 to 24 years and 25 to 29 years. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 5 report the results, showing that the effect of the closure is limited to the younger group. The marriage rate for men older than 30 years is above 90 percent and robust over time (see Table 1). Our results are thus consistent with the view that the decision to get married at an older age is largely driven by social rather than economic factors. Columns (3) and (4) of Table 5 report the estimates for educated individuals (more than 12 years of schooling) and less-educated individuals separately. The estimates are negative for both groups but only significant and much larger for less-educated men. In column (6), we run a triple difference model to estimate the different impacts of the closure on educated and uneducated men within localities before and after the shock, controlling for the locality-unobserved time-varying variables (locality-by-year fixed effects) and allowing for the different impacts of education on marriage across localities. The coefficient of the triple interaction (education dummy (one for uneducated) - share of commuters - time dummy) is negative and significant, confirming the results in columns (4) and (5).

The heterogeneous analyses further support our identification strategy and the labor market mechanism. Commuters, on average, are younger and less-educated than non-commuters. The closure affected uneducated and unskilled workers most, with jobs in government, large companies, and the health and education sectors (mostly skilled workers) being relatively stable. For the change in labor market outcome to be the true mechanism, marriage rates among less-educated men should fall more than those among more-educated men and more so in hard-hit localities. This is what the triple difference model shows, thereby strengthening our identification by controlling for the locality-unobserved time-varying variables that might be correlated with the pre-shock commuting share.

We run two extra robustness checks. Table 6 reports the estimates for a binary treatment model for different specifications. Here, a locality is considered as treated if its commuting share in 1999 is larger than that of the median locality and untreated otherwise. The estimates are negative, precise, and robust. Marriage in treated localities declined by 8 percentage points more than in untreated localities before and after the shock. Finally, we apply Fisher’s randomization approach to derive the empirical distribution of the placebo coefficients β for 5000 permutations, as shown in Fig. 5. Then, we calculate the p value of the DiD estimate in column (1) in Table 3 using the empirical distribution. We still reject the null of a zero effect at very small level (p value = 0.0014).

Fisher test. The figure plots the empirical distribution of the estimates of the coefficients of the interaction term Share1999placebo × T, as in column (1) in Table 3. The placebo commuting share in 1999, Share1999placebo, refers to a randomly assigned commuting share drawn from the 1999 commuting shares. This estimation was conducted 5000 times. The vertical line indicates the point estimate reported in column (1) of Table 3

8 Discussion

The strong connection between economic shocks and declining male marriage rates in the West Bank runs contrary to what might be expected by just considering religious practice and customs around the directionality of nuptial gifts.

Social and religious emphasis on the importance of marriage and the explicit encouragement of families to ease financial and economic barriers to marriageFootnote 13, especially during times of economic hardship, might have contributed to delinking economic shocks and marriage in the predominantly religiously conservative West Bank. And yet, we observe falling marriage rates after negative economic shocks. Other studies have pointed to how the historically high marriage rates in Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries seem to have been falling among young people in response to, at least partially, worsening labor market conditions (Anukriti & Dasgupta, 2018; Rashad et al., 2005; Singerman, 2008). Our finding confirms empirically the negative causal link between shocks and marriage.

It is not surprising then that the issue of high and persistent wedding costs has gained increasing public attention in some Middle Eastern countries over the past two decades (Al-Monitor, 2016; Aljazeeera, 2017; Arab News, 2009; Brookings, 2008). However, although the issue is widely acknowledged and hotly debated, official statistics on wedding costs are yet to be released across the region.Footnote 14 According to the few limited surveys, ethnographic research, and media sources, wedding costs are significant in the Middle East, amounting to several times the annual income of an average worker (Krafft & Assaad, 2020; Singerman, 2008; Singerman & Ibrahim, 2003). Our study indicates that, in addition to the demographic transition, such stubborn and high wedding costs might be an important factor contributing to the decline in men marriage rates among the conservative population in the Middle East in times of economic hardship and rising unemployment.

Our findings also run to the contrary of the more recent literature Corno et al. (2020) on the topic that pointed to the role of the direction of nuptial gifting as the determinant of the direction of the link between economic shocks and marriage. Whereby bride-price-giving societies in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrated a decline in the female marriage rate in response to a negative economic shock, dowry-giving communities in India did not (Corno et al., 2020). In contrast, we find that male marriage rates declined in the West Bank following a negative economic shock even though the direction of resource transfer goes from the groom to the bride (including bride price or mehr and any other marriage expenses).

When compared to sub-Saharan Africa, which comprises predominantly low-income countries, wedding ceremony costs in the West Bank dwarf mehr as well as the direct resource transfer from the groom to the bride. Even if families are willing to compromise on the bride price as in sub-Saharan Africa, wedding costs, which represent most marriage expenses, remain rigid. Indeed, average wedding costs can be US $10,000–$30,000, approximately two to six times the median annual income. The potential decline in mehr in response to negative economic shocks, motivated by religious rules and shown to be large in other Muslim-majority countries (Ambrus et al., 2010; Anderson, 2007; Carroll, 1986; Chowdhury et al., 2020; Farzanegan & Gholipour, 2016; Makino, 2019; Rapoport, 2000), does not lead to higher marriage rates in the West Bank, as the potentially rigid and expensive wedding ceremony practices become a huge burden in times of economic hardship. Meanwhile, the much-needed naqout (a common wedding tradition by which invitees donate money to the groom, usually cash money in a sealed envelope) is expected to fall short of the groom’s expectations, exacerbating the financial burden of marriage.

Practices around the costs of marriage in the West Bank are likely rigid and irresponsive, thereby keeping the “price” of marriage out of the reach of young men struggling with the adverse economic effects of border closures. In fact, one can reconcile our results with those of Corno et al. (2020) by introducing fixed costs of marriage to their theoretical model. Depending on the relative size of the fixed costs to the variable costs of marriage, a negative economic shock could conceptually lead to higher/lower male marriage rates in bride-price-giving societies. Nevertheless, we are unable to formally test the hypothesis for the rigid wedding customs in the West Bank due to data limitation. We leave this for future work as more detailed data emerge about the costs of marriage in the West Bank.

Overall, our results contribute to highlighting the complex causal linkages that can exist between economic shocks and marriage decisions. A singular consideration of just one custom, such as the direction of resource transfer or religious teachings, is not enough to understand the role played by social factors, including religious, cultural, and economic ones, surrounding marriage customs (e.g., the amount of money paid by the groom to the bride and her family (bride price) and other marriage costs, especially wedding ceremonies). But it is apparent that financial expectations do not adjust quickly enough to accommodate declining economic conditions, putting the personal and social lives of young men and their potential future partners at the mercy of highly unpredictable and shock-prone economic cycles.

9 Conclusion

Marriage, while primarily a personal endeavor and a social institution, is also an economic decision. Economists have long strived to explain the connection between the economy and marriage decisions. Despite early theorizations that negative economic shocks reduce the attraction of potential partners, more recent studies on women’s marriage have shown that cultural practices can play a detrimental role in deciding the direction of this relationship. This study contributes to this strand of the literature by investigating the causal links between a male-specific negative economic shock and marriage decisions amongst men in a Middle Eastern Muslim-majority community using data from the West Bank.

We find that the sudden Israeli labor market closure to commuters, mostly young men, from the West Bank following the Second Intifada in 2001 led to a significant reduction in their marriage rates. The higher the dependence on commuting jobs in Israel, the larger is the subsequent fall in marriage rates. On average, each additional one standard deviation rise in the share of commuters in total employment leads to a 10 percent reduction in the men’s marriage rate. The reasons for the significance of these findings are twofold. First, they highlight the rigidity of social norms and expectations governing marriage costs even when religious teachings encourage flexibility. Young men, and their respective families, find it harder to finalize marriages and to fulfill family expectations of marriage costs and financial obligations during economic shocks. Families are more willing to delay marriage than to lower their financial expectations from the groom and his family even when the shock is systemic and affects the entire community. Second, our findings run contrary to some of the more recent literature that has postulated a negative relationship between marriage and economic shocks in societies governed by a bride price. In this economic and sociocultural context (i.e., a middle-income Muslim-majority Arab country in which marriage is still governed by the bride price custom), we observe that men faced with an adverse economic shock are less likely to marry as families with daughters eligible for marriage do not respond to the economic crisis by reducing their financial requirements from the groom’s family either under the auspices of religious teachings or for purposes of consumption smoothing. This suggests that, in middle-income countries, maintaining the economic and social status of the bride’s family is more valuable than the short-term gain from the bride price and a reduction in household size - even during economic shocks.

Our findings point out the social costs that accompany the severe political retaliation policy of the Israeli labor market closure. Overdependence on commuting not only exposes the economy to the volatilities of the political situation but also permeates the social sphere. In Muslim-majority countries in which premarital affairs are rare and socially proscribed, the impacts of youth unemployment extend beyond economic welfare to affect the social and personal lives of young people and obstruct the fulfillment of some of the basic constituents of adult life. Governments in the region concerned with dwindling marriage rates are thus better served by focusing on domestic employment-generation policies than on awareness campaigns encouraging families to reduce the financial barriers to marriage.

Data availability

The PLFS datasets used in this paper are proprietary and were obtained from the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). We cannot make them available online. However, a researcher can easily (perhaps freely) obtain the data, as PCBS is required by law to provide it in a “fair and impartial way.” The dataset on the number of fatalities is publicly available at the B’TSELEM website.

Code availability

We will, of course, supply all the code used in producing the results in the paper and will gladly assist in any request to obtain the data.

Notes

Due to data limitations, we do not formally test for the rigid wedding customs hypothesis, but we leave this for future work.

The First Intifada started in 1987 and eventually ended with the Oslo Accords in 1993. This was a relatively peaceful and less violent and deadly struggle against Israeli occupation than the Second Intifada.

In a fundamental departure from the previous short-term measures implemented to reduce Palestinians’ access to Israel in times of political turbulence, Israel started to implement the long-term policy of replacing Palestinian workers by non-Palestinians by building a wall (the Separation Wall) to stop Palestinians from entering Israel (Mansour, 2010; Saad & Fallah, 2020). The share of commuters slowly recovered in the years following the Second Intifada, but never reached the pre-Intifada level.

Rashad et al. (2005) discuss the need to understand the exact causal linkages between the labor and marriage markets in the region.

Unmarried men face huge societal pressures to get married to preserve their own and their family’s social stance. Cohabitation and relationships outside marriage are prohibited in the conservative society of the West Bank, rendering marriage a virtue and necessity.

The marriage expenses usually include mehr (the traditional bride price) in addition to an array of expenses such as jewelry, gifts, home furnishings, and the wedding ceremony. In many Muslim-majority countries in the region, mehr is divided into two parts: moajel (advance payment) specifies the amount transferred from the groom to the bride at the time of marriage and moaker (deferred payment) is the amount transferred by the groom upon divorce. The moajel specified in the marriage contract is usually small in the West Bank and some Middle Eastern countries (Ambrus et al., 2010; Makino, 2019; Rapoport, 2000). Nonetheless, the non-contractual but widespread customary practices such as giving jewelry gifts and covering wedding expenses entail substantial transfers and costs. In addition, the arrangements of the marriage ceremony follow prevalent, rigid, and costly customary practices, adding even more financial burden onto the groom.

As pointed by Singerman (2008), delayed marriage comes with significant costs, especially in societies in which adulthood is linked to marriage, as in Egypt, Jordan, and Palestine, among others.

Marriage spillover across localities might weaken our identification as well. This will be the case if men from control localities get married from hard-hit localities, benefiting from harsh economic conditions and potentially lower marriage costs in those localities. We argue that this is highly unlikely in the West Bank. As mentioned in Section (3), more than 40 percent of marriages in the West Bank are among first cousins who usually live in the same locality. The number is much higher if marriages within the same extended family are considered, reaching over 60 percent, especially in rural and small localities. Additionally, if this mechanism is at play, we expect to see a slightly higher population growth in control localities compared to the treated localities after the shock. We do not find any differential effect of the shock on population growth or the size of household across localities.

Each randomly chosen household is sampled four times in total: rounds x, x + 1, x + 4, and x + 5. Hence, for each quarter, around 50 percent of households are sampled for the first time. We drop repeated panel observations, except for the first appearance. Therefore, the final sample consists of randomly repeated cross-sectional observations, as presented in the study’s proposed econometric specifications.

Further tests of the preexisting trends require a long period before the shock (Kahn-Lang & Lang, 2020). Unfortunately, data before 1999 are not readily available.

This is possible in Palestine because it is common for young married adults to live with their parents.

Islamic teachings include numerous verses that urge men to get married and form families whenever possible. Extramarital affairs are forbidden and perceived as one of the biggest sins. As a result, marriage is the only viable and socially acceptable avenue for having relationships and forming families.

Exceptions include the 2006, 2012, and 2016 Labor Market Panel Surveys in Egypt and Jordan administered by the Research Economic Forum, which provide detailed information on marriage costs. Unfortunately, such data do not exist for the West Bank.

References

Abrahams, A. (2018). Hard traveling: commuting costs and urban unemployment with deficient labor demand. ESOC Working Papers 8, Empirical Studies of Conflict Project.

Al-Monitor. (2016). Palestinian wedding season can hit the wallet hard. https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/afp/2016/08/palestinians-economy-social-weddings.html. Accessed 22 August 2020.

Aljazeeera. (2017). Saving gaza’s marriage. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/02/saving-gaza-marriages-170226125049354.html. Accessed 22 August.

Ambrus, A., Field, E., & Torero, M. (2010). Muslim family law, prenuptial agreements, and the emergence of dowry in Bangladesh. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125, 1349–1397.

Amin, S., & Al-Bassusi, N. H. (2004). Education, wage work, and marriage: perspectives of egyptian working women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1287–1299.

Amin, S., Asadullah, N., Hossain, S., & Wahhaj, Z. (2017). Can conditional transfers eradicate child marriage? Economic and Political Weekly, 52, commentary published 11 Feb, 2017.

Amodio, F., & Di Maio, M. (2018). Making do with what you have: conflict, input misallocation and firm performance. The Economic Journal, 128, 2559–2612.

Amodio, F., Baccini, L., & Di Maio, M. (2021). Security, trade, and political violence. Journal of European Economic Association, 19, 1–37.

Anderson, S. (2007). The economics of dowry and brideprice. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 151–174.

Angrist, J. D. (1995). The economic returns to schooling in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. American Economic Review, 85, 1065–1087.

Angrist, J. D. (1996). Short-run demand for palestinian labor. Journal of Labor Economics, 14, 425–453.

Anukriti, S. & Dasgupta, S. (2018). Marriage markets in developing countries. In S. L. Averett, L. M. Argus, & S. D. Hoffman (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Arab News. (2019). Wedding costs: traditions and reality. https://www.arabnews.com/node/328902. Accessed 19 August 2020.

Asadullah, M. N., & Wahhaj, Z. (2019). Early marriage, social networks and the transmission of norms. Economica, 86, 801–831.

Assaad, R., Binzel, C., & Gadallah, M. (2010). Transitions to employment and marriage among young men in egypt. Middle East Development Journal, 2, 39–88.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. (2019). When work disappears: manufacturing decline and the falling marriage market value of young men. American Economic Review: Insights, 1, 161–78.

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part i. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Bishai, D., & Grossbard, S. (2010). Far above rubies: bride price and extramarital sexual relations in uganda. Journal of Population Economics, 23, 1177–1187.

Brandt, L., Siow, A., & Vogel, C. (2016). Large demographic shocks and small changes in the marriage market. Journal of the European Economic Association, 14, 1437–1468.

Brookings. (2008). The middle east marriage crisis. https://www.brookings.edu/on-the-record/the-middle-eastern-marriage-crisis/. Accessed 19 August 2020.

Brück, T., Di Maio, M., & Miaari, S. H. (2019). Learning the hard way: the effect of violent conflict on student academic achievement. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17, 1502–1537.

Carroll, L. (1986). A note on the muslim wife’s right to divorce in pakistan and bangladesh. New Community, 13, 94–98.

Chowdhury, S., Mallick, D., & Chowdhury, P. (2020). Natural shocks and marriage markets: fluctuations in mehr and dowry in muslim marriages. European Economic Review, 128, 103510.

Chu, J., Liu, H., & Png, I. P. L. (2018). Nonlabor income and age at marriage: evidence from China’s heating policy. Demography, 55, 2345–2370.

Corno, L., Hildebrandt, N., & Voena, A. (2020). Age of marriage, weather shocks, and the direction of marriage payments. Econometrica, 88, 879–915.

Di Maio, M., & Nandi, T. K. (2013). The effect of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict on child labor and school attendance in the West Bank. Journal of Development Economics, 100, 107–116.

Di Maio, M. & Nisticó, R. (2019). The effect of parental job loss on child school dropout: evidence from the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Journal of Development Economics, 141, 102375.

Fallah, B., Bergolo, M., Saadeh, I., Abu Hashhash, A., & Hattawy, M. (2021). The effect of labour-demand shocks on women’s participation in the labor force: evidence from palestine. The Journal of Development Studies, 57, 400–416.

Farsakh, L. (2002). Palestinian labor flows to the Israeli Economy: a finished story? Journal of Palestine Studies, 32, 13–27.

Farzanegan, M. R., & Gholipour, H. F. (2016). Divorce and the cost of housing: evidence from Iran. Review of Economics of the Household, 14, 1029–1054.

Field, E., & Ambrus, A. (2008). Early marriage, age of menarche, and female schooling attainment in bangladesh. Journal of Political Economy, 116, 881–930.

Granqvist, H. (1934). Marriage in palestine. The Muslim World, 24, 49–52.

Granqvist, H. (1935) Marriage conditions in a Palestinian village. (Helsingfors [Akademische buchhandlung].

Jad, I. (2009). The politics of group weddings in palestine: political and gender tensions. Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies, 5, 36–53.

Jarallah, Y. (2008). Marriage patterns in palestine. Age, 25, 30–34.

Johnson, P. (2010). Unmarried in palestine: embodiment and (dis) empowerment in the lives of single palestinian women. IDS Bulletin, 41, 106–115.

Kahn-Lang, A., & Lang, K. (2020). The promise and pitfalls of differences-in-differences: reflections on 16 and pregnant and other applications. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 38, 613–620.

Kearney, M. S., & Wilson, R. (2018). Male earnings, marriageable men, and nonmarital fertility: evidence from the fracking boom. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 100, 678–690.

Kis-Katos, K., Pieters, J., & Sparrow, R. (2018). Globalization and social change: gender-specific effects of trade liberalization in Indonesia. IMF Economic Review, 66, 763–793.

Krafft, C., & Assaad, R. (2020). Employment’s role in enabling and constraining marriage in the Middle East and North Africa. Demography, 57, 2297–2325.

Kressel, G. M. et al.(1977). Bride-price reconsidered [and comments]. Current Anthropology, 18, 441–458.

Loughran, D. S., & Zissimopoulos, J. M. (2009). Why wait? the effect of marriage and childbearing on the wages of men and women. Journal of Human Resources, 44, 326–349.

Makino, M. (2019). Marriage, dowry, and women’s status in rural Punjab, Pakistan. Journal of Population Economics, 32, 769–797.

Mansour, H. (2010). The effects of labor supply shocks on labor market outcomes: evidence from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Labour Economics, 17, 930–939.

Miaari, S., & Sauer, R. (2011). The labor market costs of conflict: closures, foreign workers, and Palestinian employment and earnings. Review of Economics of the Household, 9, 129–148.

Miaari, S., Zussman, A., & Zussman, N. (2014). Employment restrictions and political violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 101, 24–44.

National Health Marriage Resources Center. (2017). Marriage trends in the middle east: a fact sheet. https://www.healthymarriageinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/MarriageMiddleEast.pdf. Accessed 19 August 2020.

Oppenheimer, V. K., Kalmijn, M., & Lim, N. (1997). Men’s career development and marriage timing during a period of rising inequality. Demography, 34, 311–330.

Palestinian Center Bureau of Statistics. (2013). Women and men in palestine, issues and statistics. Technical Report, Palestinian Center Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah, West Bank.

Palestinian Center Bureau of Statistics. (2018). Press release on the eve of international women’s day. Technical Report, Palestinian Center Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah, West Bank.

Rapoport, Y. (2000). Matrimonial gifts in early islamic egypt. Islamic Law and Society, 7, 1–36.

Rashad, H., Osman, M. & Roudi-Fahimi, F. (2005). Marriage in the arab world. Technical Report, Population Reference Bureau, Washington, DC.

Rexer, J. M. (2022). The brides of boko haram: economic shocks, marriage practices, and insurgency in nigeria. The Economic Journal, 132, 1927–1977.

Rotz, D. (2016). Why have divorce rates fallen?: the role of women’s age at marriage. Journal of Human Resources, 51, 961–1002.

Ruppert Blumer, E. (2003). The impact of Israeli Border Policy on the Palestinian Labor Market. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 51, 657–676.

Saad, A. F. (2015). The impact of remittances on key macroeconomic variables: the case of Palestine. Working Paper, The Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS).

Saad, A. F., & Fallah, B. (2020). How educational choices respond to large labor market shocks: evidence from a natural experiment. Labour Economics, 66, 101901.

Schaller, J. (2013). For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1007–1033.

Schneider, D., & Hastings, O. (2015). Socioeconomic variation in the effect of economic conditions on marriage and nonmarital fertility in the United States: evidence from the great recession. Demography, 52, 1893–1915.

Singerman, D. (2008). The economic imperatives of marriage: emerging practices and identities among youth in the middle east. Working Papers 6, Middle East Youth Initiative.

Singerman, D., & Ibrahim, B. (2003). The cost of marriage in egypt: a hidden variable in the new arab demography. Cairo Papers in Social Science, 24, 80–166.

Warner, W. L. (1937). Marriage conditions in a palestinian village, vol. ii. hilma granqvist. American Journal of Sociology, 42, 598–599.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Zimring, A. (2019). Testing the Heckscher-Ohlin-Vanek theory with a natural experiment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 52, 58–92.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. We thank Serena Canaan and the seminar participants at the Doha Institute for Graduate Studies for their useful comments. All remaining errors are our own.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ragab, A., Saad, A.F. The effects of a negative economic shock on male marriage in the West Bank. Rev Econ Household 21, 789–814 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09615-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-022-09615-9