Abstract

We analyze causes of the surge in defaults experienced by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac during the Great Recession. Our data are consistent with the following: The two faced a trade-off between subsidized risk-taking (due to a guarantee implied by their charters) and franchise value (due to the scarcity of their charters). Around 2005 there was a change in the relative benefits of the two due to increased competition from “private label” securities. Along with declines in house prices, the increase in defaults is best explained by exercising an option to change strategy, before regulators fully caught on, toward newer, riskier loan types, after the decline in franchise value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Frame et al. (2015a) discusses the conservatorship and some background and implications.

The preferred stock carried a 10% dividend, which was funded out of later capital injections from the Treasury.

See Wall (2014) for a discussion of what was paid back. Since 20,120 dividend payments have stopped and Treasury takes all the net income.

The market value of the PLS dropped quickly as the crisis hit, but subsequent losses to the GSEs were small. As of the last (2013) Conservator Report they had made a small cumulative “profit” (cash flow) on PLS of around $20 billion.

This market is the one where mortgage-backed other than those guaranteed by Fannie, Freddie and Ginnie Mae trade. These were typically structured deals set up by Wall Street banks.

The FICO score comes from a proprietary algorithm formulated by the Fair Isaac Corporation. According to the Federal Reserve (2007), payment history accounts for about 35% of the FICO score’s predictive accuracy; consumer indebtedness accounts for about 30%; length of credit history, 15%; and types of credit used and acquisition of new credit, each about 10%.

Occasional “stand-alone” ratings usually put the two in the low AA range.

It has at times been an issue. For instance in the late 1970s and early 1980s Fannie Mae suffered large losses from funding long term mortgages with short term debt. Pass-through securities have very little interest rate risk.

Deals with Alt-A and Jumbo loans had lower levels of subordination. See FCIC ( 2011).

For instance not having to document the source of downpayment makes it easy to fund the downpayment with a second mortgage, which increases default probability in itself and may be an indicator of other risks.

Even managements that always want to maximize the probability of survival will sometimes switch to large risk-taking if they have been sufficiently unlucky for instance because safe strategies will ensure losses.

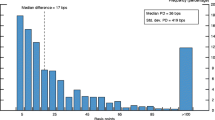

They do not explicitly consider Alt-A loans, but as can be seen from Fig. 2 the Alt-A market moved in more or less the same way as the subprime market.

C.f. Fannie Mae Presentation, “Single Family Guarantee Business- Facing Strategic Crossroads,” June 27, 2005 and Chapter 9 of FCIC Final Report: “Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Two Stark Choices.”

Capital requirements were essentially the maximum of capital needed to pass a stress test and a separate minimum capital ratio. On the GSE stress tests and their performance see Frame et al. (2015b). They came to results similar to ours of a shift in the default function.

There were also contract provisions that allowed GSE to put mortgages back to sellers for contract violations.

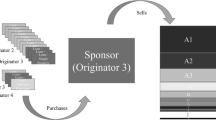

For the remaining 10% there was some sort of risk-sharing (required by charter). Contracts with sellers often required buybacks when contract terms had been violated.

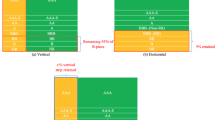

Note again that differences are even larger than depicted in the table because these raw data do not adjust for later vintage loans having less time to default. We make an adjustment for this in our estimation in the next section.

Negative amortizing loans were not the issue as much as other factors. They defaulted at a 39% lower rate than the overall book of business. Loans with no-or-negative amortization features are more likely to be underwater because they have a higher residual unpaid principal balance, but this effect is negligible given the timeframe involved.

PSA or Public Securities Administration is a simple benchmark that is often used for quoting yields on mortgages based on a simple model of prepayments.

This is the parameter estimate exponentiated, i.e. e1.36 = 3.9.

This is the parameter estimate exponentiated minus one, i.e. e-0.75 = 0.47–1 = −0.53.

Deng et al. (2000) find a similar result.

This is the parameter estimate exponentiated minus one, i.e. e-0.78 = 0.45–1 = −0.54.

In unreported regressions, the results in this section are replicated using a logit model instead of the proportional hazards and a “probability of underwater” variable in place of Market LTV.

We conjecture that the very high coefficients for the first two years come from the very low probability of loans form this vintage had negative equity, and that the Gaussian distribution underestimates tail events. There are still effects for LTV at 80 and at 90, suggesting as before that these loans have something to hide.

The very high coefficients for probability of negative equity for 2001 and 2002 probably reflects shortcomings in the negative equity measure.. That is our measure makes that number very small, but there were still defaults, so high coefficients are needed to fit those two years.

They have loan level data and know exposure year as well as origination year and simultaneously estimate prepayment

In an earlier version of this paper we performed Granger Causality tests, which confirm what is clear from looking at the timing.

References

Acharya, V., Richardson M., Van Neuerburg S., White L. (2011). Guaranteed to fail: Fannie Mae, Freddie mac, and the debacle of mortgage finance.

Ai, C., & Norton, E. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Anderson, C., Capozza D. and Van Order R. (2011). Deconstructing the subprime debacle using new indices of underwriting quality and economic conditions: A first look. Journal of Money Credit and Banking.

Ashcraft, A. B., & Schuermann, T. (2007). Understanding the Securitization of Subprime Mortgage Credit. New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Blinder, A. (2013). After the Music Stopped: The Financial Crisis, the Response, and the Work Ahead.

Buser, S., Chen, A., & Kane, E. (1981). Federal Deposit Insurance, regulatory policy, and optimal Bank capital. The Journal of Finance., 36(1), 51–60 March.

Demyanyk, Y., & Van Hemert, O. (2011). Understanding the subprime mortgage crisis. Review of Financial Studies., 24(6), 1848–1880.

Deng, Quigley, & Van Order. (2000). Mortgage terminations, heterogeneity and the exercise of mortgage options. Econometrica, 68(2), 275–307.

Federal Housing Finance Agency. (2018). Enterprise Capital Requirements: Notice of Proposed Rule https://www.fhfa.gov/SupervisionRegulation/Rules/Pages/Enterprise-Capital-Requirements.aspx

Federal Reserve (2007) http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/rptcongress/creditscore/creditscore.pdf

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission (2011). The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States"The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States. Washington, D. C.: Government Printing OffiCe. Available at http://www.fcic.gov/resource/reports

Foote, C., Gerardi, K., & Goette, L. (2009). Reducing Foreclosures: No Easy Answers. NBER Macroeconomics Annual, 24, 89–138.

Foster, C., & Van Order, R. (1984). An Option Based Model of Mortgage Default. Housing Finance Review, 3(1), 351–372.

Frame, W. S., & White, L. (2007). Charter value, risk-taking incentives, and emerging competition for Fannie Mae and Freddie mac. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39(1), 83–103.

Frame, W. S., Fuster, A., Tracy, J., & Vickery, J. (2015a). The Rescue of Fannie Mae and Freddie mac. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(2), 25–52.

Frame, K., Gerardi, S., Willen, P. S. (2015b). The Failure of Supervisory Stress Testing: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and OFHEO. https://www.bostonfed.org/-/media/Documents/Workingpapers/PDF/wp1504

Gorton, G. (2010). Slapped in the face by the invisible hand: The panic of 2007. Oxford University Press.

Guiso, L, Sapienza, P, Zingales L. (2013). Moral and social constraints to strategic defaults on mortgages. Journal of Finance.

Hernandez-Murillo, R, Ghent, A., Owyang M. (2012) Did affordable housing legislation contribute to the subprime securities boom? March 2012.

Jaffee, D. (2003). The interest rate risk of Fannie Mae and Freddie mac. Journal of Financial Services Research, 24(1), 5–29.

Kau, J., & Keenan, D. (1995). An overview of option-theoretic pricing of mortgages. The Journal of Housing Research, 6(2), 217–244.

Kau, J., Keenan, D., Muller, W., & Epperson, J. (1992). A generalized valuation model for fixed-rate residential mortgages. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 24(3), 279–299.

Keeley, M. Deposit Insurance, Risk, and Market Power in Banking. (1990). The American economic review Vol. 80, no. 5 pp. 1183–1200 December.

Keys, B., Mukherjee, T. K., Seru, A., & Vig, V. (2010). Did securitization Lead to lax screening? Evidence from subprime loans. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125.

Lai, R. N., & Van Order, R. A. (2014). Risk-taking, Securitization and the Option to Change Strategy. Real Estate Economics, 42(2), 343–362.

Loutskina, E., & Strahan, P. (2009). Securitization and the Declining Impact of Bank Finance on Loan Supply: Evidence from Mortgage Acceptance Rates. Journal of Finance, 64, 861–889.

Marcus, A. J. (1984). Deregulation and bank financial policy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 8(4), 557–565.

Mayer, C., Pence, K., Sherlund, S. (2009). “The rise in mortgage defaults,” Journal of Economic Perspectives. 23(1) Winter 2009—Pages 27–50.

Merton, R. C. (1977). An Analytic Derivation of the Cost of Deposit Insurance and Loan Guarantees. Journal of Banking and Finance, 1, 3–11.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2009). The consequences of mortgage credit expansion: Evidence from the U.S. mortgage default crisis. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), 1449–1496 November.

Min, David. (2012). Faulty conclusions, based on shoddy foundations. Center for American Progress.www.americanprogress.org

Pinto, E. (2010). Government housing policies in the Lead-up to the financial crisis: A forensic study. November 4, 2010, available at http://www.aei.org/docLib/Government-Housing-Policies-Financial-Crisis-Pinto-102110.pdf.

Rajan, R. (2010). Fault Lines. Princeton University Press.

Roll, R. (2003). Benefits to homeowners from mortgage portfolios retained by Fannie Mae and Freddie mac. Journal of Financial Services Research, 23(1), 29–42.

Saunders, A., Wilson B. (2001)An Analysis of Bank Charter Value and Its Risk-Constraining Incentives. Journal of Financial Services Research, Vol. 19, No. 2/3, April.

Vandell, K. (1995). How ruthless is mortgage default? A review and synthesis of the evidence. Journal of Housing Research, 6(2), 245–264.

Wall, L. (2014) Have the Government-Sponsored Enterprises Fully Repaid the Treasury? Notes from the Vault. Atlanta Fed. March 2014.

Wallison, P. J., & Calomiris, C. W. (2009). The Last Trillion-Dollar Commitment: The Destruction of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Journal of Structured Finance, 15(1), 71–80.

White, L. (2003). Focusing on Fannie and Freddie: The Dilemma of Reforming Housing Finance. Journal of Financial Services Research, 23(1), 43–58.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, J., Van Order, R. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac: Risk-Taking and the Option to Change Strategy. J Real Estate Finan Econ 60, 270–307 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-018-9679-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-018-9679-7