Abstract

Energetic properties of chlorophylls in photosynthetic complexes are strongly modulated by their interaction with the protein matrix and by inter-pigment coupling. This spectral tuning is especially striking in photosystem I (PSI) complexes that contain low-energy chlorophylls emitting above 700 nm. Such low-energy chlorophylls have been observed in cyanobacterial PSI, algal and plant PSI–LHCI complexes, and individual light-harvesting complex I (LHCI) proteins. However, there has been no direct evidence of their presence in algal PSI core complexes lacking LHCI. In order to determine the lowest-energy states of chlorophylls and their dynamics in algal PSI antenna systems, we performed time-resolved fluorescence measurements at 77 K for PSI core and PSI–LHCI complexes isolated from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The pool of low-energy chlorophylls observed in PSI cores is generally smaller and less red-shifted than that observed in PSI–LHCI complexes. Excitation energy equilibration between bulk and low-energy chlorophylls in the PSI–LHCI complexes at 77 K leads to population of excited states that are less red-shifted (by ~ 12 nm) than at room temperature. On the other hand, analysis of the detection wavelength dependence of the effective trapping time of bulk excitations in the PSI core at 77 K provided evidence for an energy threshold at ~ 675 nm, above which trapping slows down. Based on these observations, we postulate that excitation energy transfer from bulk to low-energy chlorophylls and from bulk to reaction center chlorophylls are thermally activated uphill processes that likely occur via higher excitonic states of energy accepting chlorophylls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photosynthesis is a process of converting solar light into chemical energy by living organisms. The first step of this process is absorption of light by one of the pigments associated with the photosynthetic apparatus. Photon absorption creates an excited state that eventually (within a few tens of picoseconds) leads to charge separation in the reaction center (RC), i.e., electron transfer between pigments acting as the primary electron donor and the primary electron acceptor. To avoid charge recombination within the primary radical pair, the system performs a series of secondary electron transfer reactions that are fast enough to compete successfully with the back reaction. However, most of the pigments present in the photosynthetic apparatus do not carry out the electron transfer processes, but rather form the extensive antenna systems responsible for collecting light and efficiently delivering the excitation energy to the RC.

In cyanobacteria, algae and higher plants, the photochemical reactions described above are carried out by two types of pigment-protein complexes: photosystem I (PSI) and photosystem II (PSII). The RC and antenna pigments of PSI are integrated within the same protein, i.e., they are bound to the same polypeptides and cannot be separated biochemically. However, in the case of higher plants and algae, PSI is equipped with additional light-harvesting complexes I (LHCI), which support the effective collection of light. Moreover, the composition of LHCI antenna system is different between higher plants and algae. Plant PSI–LHCI complexes contain four LHCI proteins labeled Lhca1–4 (Scheller et al. 2001; Ben-Shem et al. 2003; Amunts et al. 2007), whereas the number of Lhca polypeptides in algal PSI–LHCI complex was estimated by different research groups to be in the range of 9–14 (Germano et al. 2002; Kargul et al. 2003; Drop et al. 2011). Cyanobacterial PSI does not possess any additional chlorophyll-binding antennae but occurs in trimeric form (Jordan et al. 2001), in contrast to plant and algal PSI that function as monomers (Germano et al. 2002; Ben-Shem et al. 2003; Kargul et al. 2003; Amunts et al. 2007; Drop et al. 2011). For comparison, the PSII RC does not contain its own antenna system but instead is incorporated into a large dimeric supercomplex containing various types of light-harvesting proteins (Caffarri et al. 2009).

Lhca polypeptides bind two types of chlorophylls, a and b, as well as carotenoids, mainly lutein and violaxanthin. It was shown for plant LHCI, on average, ten chlorophylls are bound to a single Lhca polypeptide (Croce and Bassi 1998). However, in the plant PSI–LHCI crystal structure (Ben-Shem et al. 2003) 56 chlorophylls are associated with the external antenna amounting to 14 chlorophylls for each Lhca complex. This discrepancy can be explained by the fact that some chlorophylls are placed at the interface between two neighboring Lhca polypeptides or between Lhca polypeptides and the PSI core and may be lost during the isolation of single polypeptides.

The monomeric PSI devoid of LHCI antennas is called a PSI core and binds 96–103 chlorophylls a and about 22 carotenoid molecules identified as beta-carotene (Jordan et al. 2001; Ben-Shem et al. 2003; Jensen et al. 2003; Haldrup et al. 2006). Almost all of these pigments form an internal antenna system. Only six chlorophylls, together with two quinones and three [4Fe–4S] iron–sulfur clusters, build the PSI electron transport chain (ETC). ETC chlorophylls and quinones are arranged in two quasi-symmetrical branches: A and B. The beginning of both branches is a heterodimer of chlorophyll a (referred to as ec1B or PB) and chlorophyll a′ (referred to as ec1A or PA), traditionally called P700, due to the approximate peak wavelength of its absorption. Another pair of cofactors (A and A0) located in each branch is composed of two chlorophylls a, labeled as ec2A and ec3A (branch A) or ec2B and ec3B (branch B). The next electron carrier in each branch is a phylloquinone molecule (A1) denoted as PhQA (branch A) or PhQB (branch B). Both branches meet at the [4Fe–4S] cluster called FX, from which the electron is transferred to the terminal acceptors—two additional [4Fe–4S] clusters denoted as FA and FB. It was shown that in algal PSI both paths of ETC are almost equally involved in the electron transport (Guergova-Kuras et al. 2001; Ramesh et al. 2004, 2007; Li et al. 2006; Redding and van der Est 2006; Giera et al. 2009; Müller et al. 2010; McConnell et al. 2015). However, it is still a matter of debate, which chlorophylls in ETC act as a primary electron donor and primary electron acceptor. According to the classical model, the primary charge separation occurs between P700 (donor) and ec3A or ec3B (acceptor), but in the last years alternative models have appeared. They are based on the hypothesis that the primary charge separation is a reversible process and occurs within the ec2A–ec3A or ec2B–ec3B pair (Müller et al. 2003, 2010; Holzwarth et al. 2005; Giera et al. 2010) with ec2A/B and ec3A/B being the primary electron donor and acceptor, respectively.

Chlorophyll a has two main absorption bands, one in the blue spectral region, called the Soret band, and the second one in the red spectral region called the Qy band. In the organic solvents, e.g., in the diethyl ether, the maximum of the Qy band is observed at ~ 660 nm for the absorption measurements and at ~ 666 nm for the fluorescence measurements (Papageorgiou 2004). However, in the case of chlorophylls embedded in the protein, their energetic (spectral) properties are tuned by their interaction with the protein matrix and also by the interaction between themselves. For example, the absorption spectrum of algal PSI core reaches a maximum for 675–676 nm (Gibasiewicz et al. 2001, 2002). This means that due to interaction with the protein the spectral characteristic of the antenna chlorophylls a is already red-shifted by ~ 15 nm compared to pure chlorophylls in organic solvents. Moreover, a unique property of PSI complexes is that they contain a relatively high amount of so-called red or long-wavelength or low-energy chlorophylls (Karapetyan et al. 2006). All these terms are traditionally used for the PSI antenna chlorophylls emitting above 700 nm, i.e., above the absorption maximum wavelength of P700. The specific spectroscopic properties of red chlorophylls may be explained by very strong excitonic interaction between two or more pigments mixed with charge transfer states (Frese et al. 2002; Ihalainen et al. 2003; Romero et al. 2009; Novoderezhkin et al. 2016). A strongly coupled dimer behaves like a single supermolecule with two electronic excited states, both of them being delocalized over the two interacting molecules and separated by the gap equal to the doubled interaction energy between their transition dipole moments (van Amerongen et al. 2000; Parson 2007). In general, one of the excitonic states is located below the excited state of monomer, whereas the second one is above the excited state of monomer (assuming relatively small displacement energy of monomers). It was shown that red chlorophylls in algal PSI–LHCI complexes start to absorb above 690 nm and reach their absorption maximum at 700 nm (Gibasiewicz et al. 2005). Thus, the absorption of red chlorophylls observed in (Gibasiewicz et al. 2005) is red-shifted compared to the absorption of bulk chlorophylls and represents the optical transition to the lower of the excitonic states. The upper excitonic states would have energies corresponding to the blue edge of bulk chlorophylls’ spectrum. Emission of red chlorophylls occurs from the lower excitonic state and is even more red-shifted then the absorption (see below) due to the large Stokes shift resulting most likely from the strong interactions between chlorophylls and mixing of the excited states with charge transfer states (Gobets et al. 1994; Frese et al. 2002; Ihalainen et al. 2003; Gibasiewicz et al. 2005; Romero et al. 2009; Novoderezhkin et al. 2016). Both effects may lead to a significant shift of the potential energy surface of the excited state and coupling of optical transitions to a distribution of phonons of higher energies.

As it is apparent from the Boltzmann distribution, the lower-energy states are occupied more favorably, particularly at low temperatures. Therefore, to identify the low-energy states in the PSI antenna, fluorescence measurements in liquid nitrogen (77 K) or liquid helium (4 K) have been performed for various PSI preparations. It was shown that in the algal PSI–LHCI complexes the steady-state emission from the lowest-energy states peaks at ~ 715 nm (Gibasiewicz et al. 2005). Energetic properties of chlorophylls in the individual algal LHCI proteins were also studied and the red-most emission was observed from Lhca2, Lhca4, and Lhca9 with maxima of emission spectra between 707 and 715 nm (Mozzo et al. 2010). It should be noted that chlorophylls located at the interface between PSI core and Lhca polypeptides may also be a potential source of long-wavelength fluorescence. In contrast, there is no direct evidence in the literature for the presence of red chlorophylls (chlorophylls emitting above 700 nm) in the algal PSI core. For comparison, the red-most chlorophylls in plant PSI–LHCI complexes are located in Lhca3 and Lhca4 and give rise to the emission at ~ 730–735 nm (Croce et al. 2000, 2002; Morosinotto et al. 2002). In order to clarify the location and properties of red chlorophylls in algal PSI we performed comparative low-temperature time-resolved fluorescence studies for PSI core and PSI–LHCI complexes.

Another important objective of our studies was to determine the wavelength dependence of the average excitation lifetime of PSI core bulk chlorophylls, defined as PSI core antenna chlorophylls emitting at wavelengths below 700 nm. Previously, the wavelength dependence of the effective trapping time has been studied for plant PSI–LHCI complexes at room temperature (Jennings et al. 2013), at 280 and 170 K (Croce et al. 2000; Jennings et al. 2003). However, the detailed analysis and discussion in the cited articles focused mainly on the long-wavelength chlorophylls. In our case, the excitation dynamics of bulk chlorophylls were precisely analyzed to draw conclusions about the trapping by charge separation in RC. Comparison of results obtained at room temperature and at 77 K allowed us to estimate the energy threshold for excitation trapping in RC and to analyze and discuss the temperature effect on the primary charge separation step in PSI.

Materials and methods

The experiments were carried out for PSI cores and PSI–LHCI complexes isolated from the green alga C. reinhardtii. Procedures of cell growth, thylakoid isolation, PSI extraction and purification were described previously (Giera et al. 2014). Preparation methods used in our work resulted in PSI core particles and PSI–LHCI complex with a Chl a/P700 ratio of 85–95 (Ramesh and Webber 2004) and ~ 180 (Gulis et al. 2008), respectively. Isolated complexes were dissolved in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 5 mM MgCl2, 12 mM CaCl2, 20% glycerol (v/v), 1 mM benzamidine, 1 mM PMSF (phenyl-methyl-sulfate fluoride), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.03% n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside. For the spectroscopic measurements at 77 K, the PSI core and PSI–LHCI solutions were suspended in 70% (v/v) glycerol, loaded into 1-cm-thick cuvettes and frozen to 77 K using a liquid nitrogen optical cryostat. It should be noted that exactly the same preparations have already been thoroughly investigated at room temperature (Giera et al. 2014).

The time-resolved fluorescence measurements were performed using a streak camera setup (Laser Centrum, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam) described in (Giera et al. 2014). The sample was excited at 400 nm with a repetition rate of 125 kHz by vertically polarized 100-fs pulses at ~ 2.4 nJ per pulse. We verified that such energy level is low enough to avoid the effect of exciton annihilation. Fluorescence was measured at a right angle with respect to the excitation beam (without any polarizer in the detection line) and recorded in three time ranges (TR): ~ 150 ps (TR1), ~ 350 ps (TR2) and ~ 1500 ps (TR3). The temporal width of the detection system response function (FWHM) was equal to ~ 3.5 ps in TR1, ~ 6 ps in TR2 and ~ 16 ps in TR3. The exposure times per image were 10–15 min for TR1, 5–6 min for TR2, and 2–2.5 min for TR3. Four images were averaged for each TR in order to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

The collected fluorescence decay kinetics were analyzed globally from 630 to 775 nm with 2.1-nm resolution using the GLOTARAN software (Snellenburg et al. 2012). The purpose of global analysis is to describe the observed time-resolved signal F(λ, t) by the sum of several components with exponential lifetimes, identical for all detection wavelengths (Holzwarth 1996):

Each component is then characterized by the decay time τj and the spectral distribution of the pre-exponential factor Aj (λ), which is commonly called the decay-associated spectrum (DAS). Streak images recorded in TR1, TR2, and TR3 were given together as input data to global analysis and fit simultaneously to obtain one set of DAS and decay times. Such a procedure allowed us to examine the excitation dynamics at broader time windows and maintain, at the same time, a good temporal resolution characteristic for shorter time ranges (see above).

The percent contribution of each component to the total fluorescence decay was estimated according to the equation:

where Ij is the integrated area of an individual DAS.

The average lifetime for particular detection wavelength was calculated as follows:

Results

PSI core

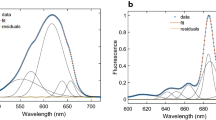

Global analysis for a PSI core revealed the existence of four components with decay times of 6 ps, 28 ps, 149 ps, and 5.3 ns. DAS of each particular component are shown in Fig. 1a. The percent contributions of particular components to the total fluorescence decay are listed in Table 1. The sum of all components’ DAS reflects the initial signal of fluorescence F(λ, t = 0). Such initial signals for the PSI core fluorescence at 77 K and room temperature (RT) are shown in Fig. 1b. The RT initial signal for the PSI core with open and closed RCs were determined based on previously published data (Giera et al. 2014). All initial signals were normalized to the same integrated area. The initial signals calculated for 77 K and RT are almost identical above 695 nm but differ at shorter wavelengths. The 77 K initial signal is much lower than the RT initial signal in the spectral region below 678 nm and higher than the RT initial signal between 678 and 695 nm. This suggests that some equilibration process between the most blue-shifted chlorophylls and the longer-wavelengths chlorophylls centered at ~ 685 nm has occurred on a time-scale shorter than the time-resolution of the experiment, i.e., shorter than 3.5 ps. Streak camera measurements do not allow for a direct observation of this downhill energy transfer, but comparison of RT and 77 K initial signals shows clearly that this process is much more efficient at 77 K. Such a fast equilibration processes occurring with a lifetime of ~ 0.5 ps was observed previously for the PSI core from C. reinhardtii in time-resolved absorption measurements (pump–probe) at RT (Gibasiewicz et al. 2001), at 77 K (Melkozernov et al. 2005) and at 10 K (Gibasiewicz et al. 2002), after excitation between 650 and 680 nm, and was also more efficient in low-temperature measurements.

a and c Fluorescence decay-associated spectra obtained by global analysis of fluorescence signals recorded at 77 K for PSI core (a) and PSI-LHCI complex (c). b and d Comparison of the initial signals of fluorescence F(λ, t = 0) at RT and at 77 K (normalized to the same area under the spectrum) for PSI core (b) and PSI–LHCI complex (d). The initial signals of fluorescence were calculated as a sum of all components’ DAS. The initial signals at RT were calculated using experimental data obtained previously at RT for PSI with open and closed RCs (Giera et al. 2014)

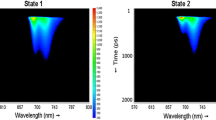

The slowest component is described by the decay time of 5.3 ns and a DAS maximum at 675 nm (Fig. 1a). Such a long-lived and blue-shifted fluorescence signal is characteristic of uncoupled chlorophylls, i.e., chlorophylls that are not properly connected to the rest of antenna system and do not transfer excitation energy to RC. The low amplitude of the 5.3-ns component indicates the presence of only a small amount of uncoupled chlorophylls in our PSI core preparations (5%). The excitation dynamics in the well-coupled antenna system of PSI core is thus described by three components: the 6-ps component with DAS maximum at 683 nm, the 28-ps component with DAS maximum at 688 nm and the 149-ps component with DAS maximum at 695 nm. The spectral shifts between them implies that the average decay time of the fluorescence signal depends strongly on the detection wavelength. The similar observation can be made by comparing kinetic traces for different detection wavelengths (Fig. 2). To illustrate this dependence more clearly we reconstructed the fluorescence decay curves in the 60-ps time window for some selected detection wavelengths on the basis of the three fastest components obtained for the PSI core at 77 K (Fig. 3a–e) and compared them with the analogous decay curves calculated for RT based on previously published data (Giera et al. 2014). The reconstructed curves present fluorescence kinetics after deconvolution of instrument response function (IRF) and are devoid of the contribution of uncoupled chlorophylls (the slowest component). The decay rate of the fluorescence signal measured at 77 K decreases with increasing detection wavelength and this dependence is noticeable not only in long-wavelength spectral region (Fig. 3d–e), as we could have expected, but also among the bulk chlorophylls (Fig. 3a–c). The second interesting observation is that below 682 nm fluorescence decay is faster at 77 K than at RT (Fig. 3a, b).

Normalized kinetic traces and fits of fluorescence decays recorded for PSI core (black lines) and PSI–LHCI complex (gray lines) at three different detection wavelengths: a 683 nm, b 695 nm, c 710 nm. A non-zero fluorescence detected before time zero represents so-called back sweep signal, i.e., fluorescence that remains after the half of the synchroscan period of streak camera and is overwritten on the initial fluorescence decay. This effect is taken into account in the global analysis, where it plays also an additional role as it allows to fit components with decay times much longer than experimental time windows

Normalized fluorescence decay curves reconstructed for the 60-ps time window on the basis of the global analysis results for PSI core (a–e) and PSI–LHCI complex (f–j) at some selected detection wavelengths: 676 nm (a, f), 682.5 nm (b, g), 686.5 nm (c, h), 691 nm (d, i), and 695 nm (e, j). Reconstruction of the RT curves was performed using experimental data obtained previously at RT for PSI with open and closed RCs (Giera et al. 2014). The longest component was excluded from the calculations, as it represents only the fluorescence decay in chlorophylls not coupled properly with the antenna system and due to its long decay time does not affect the kinetics observed in the first 60 ps of fluorescence decay

PSI–LHCI

The fluorescence decay in PSI–LHCI complexes can be also fitted with four components. However, they differ from the PSI core components, both in spectral shape (Fig. 1c) and decay times (8 ps, 37 ps, 284 ps, and 4.8 ns). The percent contributions of particular components to the total fluorescence decay are listed in Table 1. The initial signal for the PSI–LHCI fluorescence at 77 K and RT, calculated in the same way as for the PSI core, is presented in Fig. 1d. The RT initial signals for PSI–LHCI with open and closed RCs were determined based on previously published data (Giera et al. 2014). The difference in the initial signals at 77 K and at RT, suggests, as in the case of PSI core, a rapid equilibration process between chlorophylls emitting below 678 nm and those emitting in the range of 678–695 nm. Time-resolved absorption measurements of PSI–LHCI complexes at 77 K indicate that this fast equilibration process occurs with a lifetime of 0.65–0.80 ps (Melkozernov et al. 2005).

The fastest fluorescence decay component resolved for PSI–LHCI is characterized by a 8-ps lifetime and DAS with maximum at ~ 680 nm. The most interesting features of the 8-ps component’s DAS are its negative values between ~ 698 and ~ 720 nm, which indicate a fluorescence rise in this spectral range. Fluorescence decay in one spectral region accompanied by fluorescence rise in another spectral region is characteristic of excitation energy equilibration between two spectrally different pools of chlorophylls. The pure energy equilibration process would be demonstrated by DAS with similar integrated areas under those positive and negative parts of spectrum. Such DAS is then very often referred to as conservative. When the same component describes processes of excitation decay and excitation equilibration, its total DAS is a sum of positive DAS characteristic for the first process and conservative DAS of the second process. It should be noted here that Ij in Eq. (2) is obtained by mathematical integration of individual DAS in the entire analyzed spectral window, i.e., it is the difference between the absolute area under the positive part of the DAS and the absolute area above the negative part of the DAS. Thus, in our calculations, presented in Table 1, the excitation equilibration process gives no net contribution to the total fluorescence decay. The 8-ps DAS shape is not conservative, i.e., the absolute integrated areas under its positive and negative portions are not equal, but rather the positive portion dominates the spectrum. Thus, this component describes two phenomena: (1) the major process of excitation decay caused by trapping in the RC, (2) the minor process of excitation equilibration between chlorophylls emitting below 698 nm and those emitting above this wavelength. The process of excitation energy equilibration occurring with a lifetime of ~ 3.5–5 ps was also observed in time-resolved absorption measurements of PSI–LHCI at 77 K (Melkozernov et al. 2005); however, the spectral properties of the transient absorption components describing this process are not perfectly consistent with the fluorescence data presented here. Streak camera measurements at RT also revealed such an equilibration process with a lifetime of ~ 5–6 ps (Ihalainen et al. 2005; Giera et al. 2014).

The slowest component with decay time of 4.8 ns and DAS maximum at 679 nm is, like in the case of the PSI-core, the most blue-shifted compared to other components’ DAS. It describes the fluorescence of typical uncoupled chlorophylls and probably also the fluorescence decay in some population of native LHCI proteins, which are poorly coupled to the rest of the antenna system or even completely dissociated from it. Dynamics of excitations occurring in the well-coupled antenna system of PSI–LHCI complexes is thus described by three components: the 8-ps component with DAS maximum at 683 nm, the 37-ps components with DAS maximum at 691, and the 284-ps component with DAS maximum at 710 nm. As in the case of PSI core, the spectral shift between them exposes the strong dependence of the fluorescence decay rate on detection wavelength (see also kinetic traces in Fig. 2). Figure 3f–j presents the fluorescence decay curves for some selected detection wavelengths reconstructed in a 60-ps time window on the basis of the three fastest components obtained for PSI–LHCI at 77 K and previously at RT (Giera et al. 2014). The fluorescence decay in the short-wavelength spectral range (below 691 nm) is faster at 77 K compared to RT. Similar observations were made above for the low-temperature fluorescence of PSI cores.

Discussion

Long-wavelength chlorophylls in PSI core

The most recent streak camera studies with plant PSI cores revealed the presence of some amount of red chlorophylls in its antenna system (Wientjes et al. 2011). In that work, the excitation trapping in plant PSI cores is described at RT mainly by the 18-ps component, which besides the main band at ~ 680 nm has also a long and prominent tail above 700 nm. Moreover, the equilibration process between bulk and red chlorophylls with a lifetime of 3-ps was observed. The maximum of the negative portion of the 3-ps component is located at ~ 720 nm that corresponds well with the peak of steady-state fluorescence spectrum measured at 77 K and presented in the same work.

In the case of our low-temperature streak-camera measurements with algal PSI core preparation, the total fluorescence signal above 700 nm is very low (Fig. 1a). The fluorescence decay of the most red-shifted core antenna chlorophylls is described by the 149-ps component. The DAS of this component has a maximum at ~ 695 nm with a very pronounced tail above this wavelength and can be fitted with the sum of five Gaussian curves (Fig. 4). The Gaussian with a maximum at 680 nm most likely describes the long decay of a small amount of bulk chlorophylls. The Gaussians with maxima at 694, 702, and 715 nm have the most significant and almost equal contribution to the total DAS, about 22–27% each. This gives only 4–5% contribution of each of these long-wavelength chlorophyll pools to the total fluorescence decay. The most long-wavelength Gaussian (maximum at 753 nm) likely represents vibrational sidebands of the chlorophyll pools mentioned above. We should stress here that the fluorescence decay below 710 nm is described also by the 28-ps component, which is dominant over the 149-ps component for wavelengths shorter than 702 nm. Consequently, the average decay time of fluorescence at 694 and 702 nm is much shorter than that at 715 nm. For comparison, the low-temperature time-resolved absorption measurements of PSI cores also revealed some long-wavelength signal at around 700 nm: the broad band with maximum at 703 nm was detected at 77 K (Melkozernov et al. 2005), whereas the pool of chlorophylls with maximum at 695 nm were seen at 10 K (Gibasiewicz et al. 2002).

It should also be noted that excitation energy transfer from bulk to long-wavelength chlorophylls in the PSI core is not directly detectable by the streak camera measurements. The DAS of the fastest component does not reach negative values, indicating the absence of a fluorescence rise, at either RT (Giera et al. 2014) or at 77 K. Only the 6-ps DAS obtained at 77 K has a steeper slope and a recess on its red side peaking at ~ 698 nm (coinciding quite well with the maximum of the 149-ps DAS, see Fig. 1a) that suggests some small contribution of the energy transfer process to this component. On the other hand, such equilibration in the PSI core from C. reinhardtii was observed by time-resolved absorption measurements at 77 K (Melkozernov et al. 2005) and at 10 K (Gibasiewicz et al. 2002), and was characterized by lifetime of 2–4 ps. In conclusion, although the excitation equilibration between bulk and long-wavelength antenna chlorophylls occurs in the PSI core, it has a relatively small (compared to PSI–LHCI) effect on the observed fluorescence dynamics.

The significantly longer lifetime of the PSI core long-wavelength antenna chlorophylls at 77 K allowed us to separate their decay (149-ps component) from the processes occurring at the shorter-wavelength region that display significantly shorter lifetimes and are described by the two fastest components. Both the 6-ps and 28-ps components contain long-wavelength flat bands, located at 705–750 nm region and at ~ 750 nm, respectively. In the case of the 28-ps components, this long-wavelength signal may be identified as a vibrational sideband. Rätsep et al. revealed that a similar fluorescence vibrational sideband is red-shifted by ~ 1200 cm−1 relative to the main band for chlorophylls in various organic solvents (Rätsep et al. 2009). In the case of the 6-ps component, the situation is not so obvious, because the long-wavelength band extends from 500 to 1300 cm−1. Whereas its most red-shifted part (~ 1200 cm−1) represents a vibrational sideband, the remainder of this band seems to have a rather different origin. Because of the short lifetime of this signal, we can exclude that it comes from the long-wavelength antenna chlorophylls (described by the 149-ps component). It is worth noting that transient absorption changes above 710 nm at RT in algal PSI core have been already reported and ascribed to the processes taking place in the RC (Müller et al. 2003). In particular, the signal in the range 750–760 nm was ascribed to the transient absorption of the primary radical pair. According to the lifetime density map presented in (Müller et al. 2003), this transient absorption signal arises with a lifetime of 6–9 ps, and reflects the rate of the primary charge separation step. However, the same lifetime describes the decay of a negative signal (photobleaching and/or stimulated emission) in the range 710–750 nm, which has not been clearly interpreted in (Müller et al. 2003). Both the lifetime and the flat spectrum of the transient absorption signal in the 710–750 nm region correspond well with our fluorescence data. Thus, we may speculate that it represents the decay of excited states of RC chlorophylls. Of course, their fast decay would then be the result of primary charge separation in the RC.

Wavelength dependence of effective trapping time

We have assumed that the two fastest phases of fluorescence decay in PSI cores at 77 K (Fig. 1a) and at RT (Giera et al. 2014) are caused exclusively by excitation quenching of well-coupled chlorophylls by RC and that they are not significantly affected by energy equilibration between spectrally different pools of chlorophylls. Consequently, the average fluorescence lifetime calculated based on these two phases (according to Eq. 3) may be regarded as the average trapping time. Moreover, we have assumed that in the case of the low-temperature measurements, fluorescence in the spectral region below 688 nm originates exclusively from bulk chlorophylls and therefore we limited our calculations to this region (Fig. 5). Thus, the contribution to trapping from long-wavelength chlorophylls (depicted by the third, 149-ps component) was excluded.

The wavelength dependence of the average excitation lifetime for the PSI core at 77 K and at RT (PSI with open or closed RC), calculated on the basis of the two fastest fluorescence decay components (according to Eq. 3). RT curves were calculated using the experimental data obtained previously at RT for PSI with open and closed RCs (Giera et al. 2014). The kBT distance from 675-nm energy threshold at RT is shown on the plot

Analysis of Fig. 5 reveals that the average decay time at 77 K increases gradually with detection wavelengths above 675 nm whereas at RT the average decay time remains constant until a slow rise begins to occur above 685 nm. Moreover, the average decay time at 77 K is shorter than at RT for the short-wavelength chlorophylls and longer for the long-wavelength chlorophylls. The threshold wavelength is ~ 685 nm if we take into account RT measurements for the PSI core with closed RCs and ~ 682 nm if we consider RT measurements for the PSI core with open RCs. The former value seems to be more suitable for comparison, because RCs remain closed during measurements at 77 K. Thus, Fig. 5 depicts in a more concise way the observations described in the “Results” section on the basis of the reconstructed fluorescence decay curves (Fig. 3a–e).

Energy threshold for trapping

At room temperature, the excitations of PSI core bulk and longer-wavelength chlorophylls are effectively trapped in the RC. However, the spectral properties of the RC are still not well known. In the target analysis of various time-resolved emission data found in the literature, the RC was modeled with spectral bands peaking at many different wavelengths: ~ 697 nm in the plant PSI core (Slavov et al. 2008), ~ 703–705 nm in the plant PSI–LHCI (Slavov et al. 2008; Snellenburg et al. 2013) and cyanobacterial PSI (Slavov et al. 2009), and ~ 712 nm in the algal PSI core (Holzwarth et al. 2005). All of the studies cited above suggest that the emission spectral band of RCs is located energetically below that of bulk chlorophylls (683 nm). However, it should be emphasized here that emission maximum cannot be equated with the RC excitation transition because of the Stokes shift. On the other hand, in our algal PSI core preparation (Giera et al. 2010) and in the red-chlorophyll-free PSI from the cyanobacteria Synechococcus WH 7803 (van Stokkum et al. 2013) no strong emission above 695 nm, which could be assigned to the excited RC, was detected at RT. Therefore, in both these cases, the excited bulk chlorophylls and excited RC were modeled as a single emitting state, i.e., it was assumed that bulk chlorophylls and RC have similar emission properties. For comparison, in the case of time-resolved absorption data collected for the algal PSI core (Müller et al. 2003, 2010), the RC was model by spectral band peaking at ~ 690 nm, that is also energetically below the absorption band maximum of bulk chlorophylls (~ 676 nm).

According to the low-temperature fluorescence data presented here for PSI cores, the fastest trapping is observed below 675 nm (6–8 ps) and then increases gradually as the detection wavelength becomes longer (Fig. 5). This may suggest that the energy threshold of trapping is located at ~ 675 nm i.e., excitation energy needs to reach this energy level to be trapped in the RC. This observation is in agreement with the previous study on the excitonic coupling in the algal PSI–RC (Gibasiewicz et al. 2003) which indicates that a band centered at 675 nm results from strong excitonic coupling between A and A0 chlorophylls. It was also shown, that the two antenna chlorophyll dimers, A38–A39 and B37–B38, located in close vicinity of the RC, may also contribute to the 675-nm excitonic band and work as a gate between the antenna and the RC. According to several previous studies (Müller et al. 2003, 2010; Holzwarth et al. 2005; Giera et al. 2010), charge separation occurs between ec2A–ec3A or ec2B–ec3B chlorophyll pairs (A and A0). In this model, excitation must be delivered to one of those chlorophyll pairs to be trapped due to charge separation. Thus, the energy threshold of trapping seems to be determined by the absorption properties of the A–A0 pairs, i.e., their excitonic band at ~ 675 nm.

The high energy threshold for trapping (~ 675 nm) is not too difficult barrier to overcome for excitations at RT. Many chlorophylls emit at RT within this spectral region or even at shorter wavelengths (see initial signal in Fig. 1b). Furthermore, a significant portion of the remaining pool of chlorophylls is located within kBT (~ 10 nm) from the trapping threshold (see Fig. 5). Therefore, average trapping time at RT remains constant for the detection wavelengths below 685 nm and increases slowly above this wavelength. At 77 K, kBT is only ~ 2 nm above the trapping threshold which results in a fast increase of the average trapping time almost immediately above 675 nm.

Fast trapping at low temperatures

The next question is why at 77 K the effective trapping lifetime for detection wavelengths below ~ 682–685 nm is shorter than at RT. If we consider the antenna chlorophylls emitting at 675 nm, i.e., those which emission overlaps with the excitonic absorption band of the A–A0 dimer, then this difference is the largest: 7 ps at 77 K versus 16 ps at RT (calculated on the basis of the two fastest components, Fig. 5). The explanation of the observed trapping acceleration may be the reversibility of the primary charge separation postulated in some recent studies (Müller et al. 2003, 2010; Holzwarth et al. 2005; Giera et al. 2010). In the “reversible” model, the emitting excited state (Ant/RC)* decays due to the charge separation process and formation of a non-emitting charge-separated state (S1), which can further evolve irreversibly into a secondary non-emitting state (S2) or undergo a back reaction leading to regeneration of the excited state:

\(\left( {{\text{Ant}}/{\text{RC}}} \right)^*{\text{ }} \rightleftarrows {\text{S1 }} \to {\text{S2}}\)

It was estimated that the free energy gap between the excited state (Ant/RC)* and the primary charge-separated state (S1) in WT PSI from C. reinhardtii is equal to 34 meV for open RCs and 23 meV for closed RCs (Giera et al. 2010). At room temperature, the ratio of backward-to-forward reaction rates is equal to 0.26 and 0.4 for open and closed RCs, respectively. Therefore, charge recombination leading to the reproduction of the excited state has a strong impact on the effective trapping time. Assuming that the free energy gap between (Ant/RC)* and S1 is the same at RT and 77 K, it can be calculated that at 77 K the backward-to-forward reaction rate ratios would be equal to 0.006 and 0.03 for open and closed RCs, respectively. Thus, at 77 K, the backward reaction can be practically neglected.

If the backward reaction in primary charge separation step is blocked at 77 K, we can expect that effective trapping time at wavelengths below the trapping threshold (below 675 nm) will be determined by the rate of the forward reaction. The decay times calculated based on forward reaction rates at RT described recently by Giera et al. (2010) would be equal to 8.8 and 11.4 ps for the PSI core in the open and closed state, respectively. These decay times are still slightly longer than those found for the shortest-wavelengths emission at 77 K. Thus, we can furthermore suppose that the forward electron transfer reaction is a temperature-dependent quantity. It is worth noting that the acceleration of the primary electron transfer reactions as the temperature is decreased was previously observed in bacterial reaction centers (Fleming et al. 1988; Kirmaier and Holten 1990; Jia et al. 1993). Interestingly, significant acceleration of excitation trapping by RCs was also observed after immobilization of cyanobacterial PSI on conducting glass at RT (Szewczyk et al. 2017a, b) and this effect was explained by the dense packing of proteins in the solid-state phase (Szewczyk et al. 2017a).

Excitation energy trapping by RCs is very often discussed in the literature in terms of “trap-limited” and “transfer-to-trap-limited” models. In the case of the “trap-limited” model, it is assumed that excitation energy equilibration between the antenna system and the RC is very fast and this equilibrium is established before the energy is trapped by the charge separation, which is a much slower process. This model implies that RC can be visited by an excitation several times before the trapping occurs. The assumption of the “transfer-to-trap-limited” model is that the excitation energy transfer from the antenna system to RC is much slower than charge separation in RC, and hence no energy equilibrium between the antenna system and the RC is established. Moreover, the trap is fully irreversible, i.e., excitation, once transferred to the trap, will not be able to escape back to the antenna. Above we have explained the acceleration of the trapping of short-wavelength excitations at low temperatures in terms of the “trap-limited” model. However, the acceleration of trapping is observed only for short-wavelength excitations and the average trapping time increases with the detection wavelength (starting from 675 nm) due to the necessity of uphill energy transfer to the RC. For long-wavelength excitations, this transfer becomes a limiting step of the trapping and the whole process can be considered rather as “transfer-to-trap-limited.”

Long-wavelength chlorophylls in PSI–LHCI

There is a general agreement that before trapping in the RC, excitations of long-wavelength chlorophylls must be transferred uphill to the bulk chlorophylls (emission maximum at ~ 683 nm) in the thermally activated process. This activation is manifested by the slow fluorescence decay of red chlorophylls. In our recent streak camera studies, we demonstrated that in algal PSI–LHCI complexes the long-wavelength signal at RT peaks at ~ 710 nm and decays with a lifetime of ~ 30 ps (Giera et al. 2014). We estimated that it constitutes about 25% of the total fluorescence decay in the intact (well-coupled) complexes. For comparison, the recent streak camera and time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) studies of plant PSI–LHCI suggest that the fluorescence decay of long-wavelength chlorophylls in this complex is described primarily by the component with a maximum at 725 nm and decay time of 68–83 ps (Wientjes et al. 2011). This component constituted ~ 43% of the total fluorescence decay signal observed in the TCSPC experiment (after excitation at 440 nm). In general, long-wavelength chlorophylls in algal PSI–LHCI are less red-shifted than those in plant complexes resulting in a shorter decay time.

Low-temperature (170 K) fluorescence measurements that employed plant PSI–LHCI (Croce et al. 2000; Jennings et al. 2003) suggested that the dynamics of long-wavelength excitations may be described by three components: (1) 55-ps with maximum at ~ 715 nm, (2) 216-ps with maximum at ~ 725 nm, and (3) 715-ps with maximum at ~ 735 nm. However, these data do not allow a precise estimation of the relative contribution of long-wavelength chlorophylls to the overall fluorescence decay. Our low-temperature data for algal PSI–LHCI preparation presented here illustrate that the decay of long-wavelength excitations at 77 K is described predominantly by the component with maximum at ~ 710 nm with a decay time of ~ 284 ps (Fig. 1c). This component contributes 22% to the overall fluorescence decay. However, it should be noted that also the 37-ps component describes the decay of a quite significant amount of long-wavelength excitations giving emission below 710 nm. The amplitude of this component below 705 nm is even higher than that of the 284-ps component. This may suggest that population of long-wavelength excitations at 77 K is blue-shifted compared to RT (Giera et al. 2014). A similar conclusion about energy transfer to long-wavelength chlorophylls can be drawn by comparing DAS of the fastest decay components obtained at RT and 77 K (Fig. 1c). This component describes not only the excitation trapping in RCs but also excitation equilibration between bulk and red chlorophylls. Its negative portion represents the fluorescence rise in the long-wavelength spectral region due to excitation transfer from bulk chlorophylls and is blue-shifted at 77 K (Fig. 1c) compared to RT (Giera et al. 2014). To analyze this process more precisely, we decomposed the fastest components’ DAS into three Gaussians (Fig. 6). The short-wavelength Gaussian with positive values and maximum at ~ 683 nm describes the decay of bulk excitations. The most long-wavelength one, also positive, with a broad spectrum and maximum at ~ 740 represents a vibrational sideband. The middle Gaussian curve, with negative values indicating fluorescence rise, peaks at 711 nm in the case of RT and at 699 nm in the case of 77 K. This 12-nm difference suggests that excitation energy transfer revealed by the 8-ps DAS occurs at 77 K to chlorophylls which are less red-shifted than the accepting chlorophyll pool at RT. Interestingly, it seems to be no transfer to long-wavelength chlorophylls from the states decaying with 37-ps lifetime (Fig. 1c). A similar observation can be made for the 28-ps component obtained for the PSI core. The most likely explanation is that different long-wavelength species are separated from each other by the short-wavelength forms. In such a case, the excitation energy transfer from the states described by the 28/37-ps DAS to the even lower-energy states would be inefficient because in the first step it requires an uphill energy transfer to shorter-wavelength forms. On the other hand, the various forms of shorter-wavelength pools decay more or less effectively due to trapping in RC.

Temperature influences excitation equilibration between bulk and red chlorophylls (described above) in the opposite way to what we would expect based on the Boltzmann distribution (Fig. 6). This observation suggests that excitation energy transfer to red chlorophylls is a thermally activated process. One of the hypotheses explaining this observation may be that energy transfer from bulk to red states occurs (only or mainly) via upper excitonic states of red chlorophylls that are located energetically above the excited states of bulk forms. In such a case, the transfer process would require thermal activation to occur. Of course the oscillator strength of the upper excitonic state would have to be sufficiently large to act as an effective excitation acceptor. The value of the oscillator strength of excitonic states depends on relative orientation of transition dipoles in the interacting monomers (van Amerongen et al. 2000; Parson 2007). In the case of aggregates with parallel or nearly parallel orientation of the monomers’ transition dipoles, virtually all oscillator strength is concentrated in the red-shifted lower excitonic band. However, excitonic calculations performed for the cyanobacterial PSI (Byrdin et al. 2002; Gibasiewicz et al. 2003) based on its crystallographic structure (Jordan et al. 2001) showed that at least eleven pairs of chlorophylls with non-parallel transition moments (including chlorophylls’ dimers within the RC) exhibit strong interaction energies (corresponding to a band splitting higher than 200 cm−1) and oscillator strength of the upper excitonic state comparable with that of the lower excitonic state. Absorption to upper excitonic states of RC chlorophylls’ dimers was observed experimentally (Gibasiewicz et al. 2003, see also “Energy threshold for trapping” section).

The effect of temperature on the equilibration between bulk and red chlorophylls has a significant impact on the interpretation of the low-temperature steady-state fluorescence spectra (Gibasiewicz et al. 2005). As we discussed above, the excitation energy transfer from bulk to the red-most chlorophylls at low temperatures is less efficient than at RT. Therefore, the increase in the intensity of long-wavelength bands with lowering the temperature, observed in steady-state fluorescence experiments (Gibasiewicz et al. 2005), is not caused by the increase of population of long-wavelength excitations. Oppositely, it can be only explained by the increase of the fluorescence quantum yield ϕf of long-wavelength excited states which is, in turn, caused by elongation of their lifetimes τ (ϕf = kf τ, where kf is a natural fluorescence rate constant). This conclusion is consistent with the long (284-ps) lifetime of the red-most excited states at 77 K resolved in global analysis (Fig. 1c).

Conclusions

The most important achievements and findings of our work are as follows:

-

1)

Time-resolved fluorescence data collected at 77 K for algal PSI core and PSI–LHCI complexes are presented. Such low-temperature fluorescence studies with high temporal resolution (~ 3.5 ps) have not been previously reported with purified PSI particles from either algae or plants.

-

2)

Comparison of the initial signals measured at 77 K and RT for algal PSI core and PSI–LHCI complexes leads to the conclusion that equilibration within bulk chlorophylls occurs very rapidly, according to a mechanism that would be based on the Boltzmann distribution. At low temperatures, the most blue-shifted excitations (< 678 nm) are transferred to the longer-wavelength chlorophylls (centered at ~ 685 nm) much more effectively than at RT. According to the transient absorption data published so far, this process occurs with a lifetime of 0.5–0.8 ps and seems not to depend strongly on temperature (Gibasiewicz et al. 2001, 2002; Melkozernov et al. 2005).

-

3)

In algal PSI core complexes, the population of chlorophylls emitting above 700 nm is much smaller than in algal PSI–LHCI complexes. The fluorescence signal of the most red-shifted core antenna chlorophylls peaks at ~ 695 nm. The excitation equilibration between bulk and long-wavelength chlorophylls in the PSI core has a minor effect on the observed fluorescence dynamics. This is in contrast to the plant PSI core, where the efficient equilibration process between bulk and red chlorophylls peaking at 720 nm occurs at RT with a lifetime of 3 ps (Wientjes et al. 2011).

-

4)

We describe for the first time how the effective trapping time of bulk excitations in PSI core depends on detection wavelength at low temperatures. At 77 K the trapping time reaches a minimal value (~ 7 ps) for chlorophylls emitting below 675 nm and rises sharply as the wavelength increases above 675 nm. Therefore, we postulate that the energy threshold for trapping is located around 675 nm and is defined by the absorption band of the A–A0 pair. It was shown previously that the upper excitonic band of this pair peaks at ~ 675 nm (Gibasiewicz et al. 2003). This observation provides further support for the hypothesis that initial charge separation occurs within this pair of chlorophylls.

-

5)

In the PSI core, the effective trapping time for chlorophylls emitting below 682 nm is shorter at 77 K than at RT. Its minimal value observed at 77 K (at < 675 nm) is ~ 7 ps, which is about 6–9 ps shorter than at RT. The acceleration of trapping at low temperatures is probably caused by slowing of the back reaction in the primary charge separation.

-

6)

The population of long-wavelength excitations present after equilibration in algal PSI–LHCI complexes is less red-shifted at 77 K than at RT. This observation suggests that excitation energy transfer from bulk to red chlorophylls is a thermally activated process and most likely occurs via the upper excitonic states of the red chlorophyll dimers (or multimers).

-

7)

Points 4 and 6 demonstrate the similarity of excitation energy transfer from bulk chlorophylls to either RC chlorophylls or to red chlorophylls: both processes occur through thermally activated pathways, likely via upper excitonic states of accepting chlorophyll dimers/multimers (Fig. 7).

Abbreviations

- PSI:

-

Photosystem I

- LHCI:

-

Light-harvesting complex I

- RC:

-

Reaction center

- ETC:

-

Electron transfer chain

- TR:

-

Time range

- DAS:

-

Decay-associated spectrum

- RT:

-

Room temperature

References

Amunts A, Drory O, Nelson N (2007) The structure of a plant photosystem I supercomplex at 3.4 A resolution. Nature 447:58–63

Ben-Shem A, Frolow F, Nelson N (2003) Crystal structure of plant photosystem I. Nature 426:630–635

Byrdin M, Jordan P, Krauss N, Fromme P, Stehlik D, Schlodder E (2002) Light harvesting in photosystem I: modeling based on the 2.5-Å structure of photosystem I from Synechococcus elongatus. Biophys J 83:433–457

Caffarri S, Kouřil R, Kereïche S, Boekema EJ, Croce R (2009) Functional architecture of higher plant photosystem II supercomplexes. EMBO J 28:3052–3063

Croce R, Bassi R (1998) The light-harvesting complex of photosystem I: pigment composition and stoichiometry. In: Garab G (ed) Photosynthesis: mechanisms and effects, vol 1. Kluver Academic Press, Dordrecht, pp 421–424

Croce R, Dorra D, Holzwarth AR, Jennings RC (2000) Fluorescence decay and spectral evolution in intact photosystem I of higher plants. Biochemistry 39:6341–6348

Croce R, Morosinotto T, Casteletti S, Breton J, Bassi R (2002) The Lhca antenna complexes of higher plants photosystem I. BBA-Bioenergetics 1556:29–40

Drop B, Webber-Birungi M, Fusetti F, Kouřil R, Redding KE, Boekema EJ, Croce R (2011) Photosystem I of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii contains nine light-harvesting complexes (Lhca) located on one side of the core. J Biol Chem 286:44878–44887

Fleming GR, Martin JL, Breton J (1988) Rates of primary electron transfer in photosynthetic reaction centers and their mechanistic implications. Nature 333:190–191

Frese RN, Palacios MA, Azzizi A, van Stokkum IHM, Kruip J, Rögner M, Karapetyan NV, Schlodder E, van Grondelle R, Dekker JP (2002) Electric field effects on red chlorophylls, β-carotenes and P700 in cyanobacterial photosystem I complexes. BBA-Bioenergetics 1554:180–191

Germano M, Yakushevska AE, Keegstra W, van Gorkom HJ, Dekker J, Boekema EJ (2002) Supramolecular organization of photosystem I and light harvesting complex I in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS Lett 525:121–125

Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, Melkozernov AN, Lin S, Woodbury NW, Blankenship RE, Webber AN (2001) Excitation dynamics in the core antenna of PS I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CC 2696 at room temperature. J Phys Chem B 105:11498–11506

Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, Lin S, Woodbury NW, Webber AN (2002) Excitation dynamics in eukaryotic PS I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CC 2696 at 10 K. Direct detection of the reaction center exciton states. J Phys Chem B 106:6322–6330

Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, Lin S, Redding K, Woodbury NW, Webber AN (2003) Excitonic interactions in wild-type and mutant PSI reaction centers. Biophys J 85:2547–2559

Gibasiewicz K, Szrajner A, Ihalainen JA, Germano M, Dekker JP, van Grondelle R (2005) Characterization of low-energy chlorophylls in the PSI–LHCI supercomplex from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. A site-selective fluorescence study. J Phys Chem B 109:21180–21186

Giera W, Gibasiewicz K, Ramesh VM, Lin S, Webber A (2009) Electron transfer from A0 to A1 in photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii occurs in both the A and B branch with 25-30-ps lifetime. Phys Chem Chem Phys 11:5186–5191

Giera W, Ramesh VM, Webber AN, van Stokkum I, van Grondelle R, Gibasiewicz K (2010) Effect of the P700 pre-oxidation and point mutations near A0 on the reversibility of the primary charge separation in photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. BBA-Bioenergetics 1797:106–112

Giera W, Szewczyk S, McConnell MD, Snellenburg J, Redding KE, van Grondelle R, Gibasiewicz K (2014) Excitation dynamics in photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Comparative studies of isolated complexes and whole cells. BBA-Bioenergetics 1837:1756–1768

Gobets B, van Amerongen H, Monshouwer R, Kruip Y, Rögner M, van Grondelle R, Dekker JP (1994) Polarized site-selected fluorescence spectroscopy of isolated photosystem I particles. BBA-Bioenergetics 1188:75–85

Guergova-Kuras M, Boudreaux B, Joliot A, Joliot P, Redding K (2001) Evidence for two active branches for electron transfer in photosystem I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:4437–4442

Gulis G, Narasimhulu VK, Fox LN, Redding KE (2008) Purification of His6-tagged photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Photosynth Res 96:51–60

Haldrup A, Jensen PE, Scheller HV (2006) The low molecular mass subunits in higher plant photosystem I. In: Golbeck JH (ed) Photosystem I. The light-driven plastocyanin: ferredoxin oxidoreductase (advances in photosynthesis and respiration), vol 24. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 139–154

Holzwarth AR (1996) Data analysis of time-resolved measurements. In: Amesz J, Hoff AJ (eds) Biophysical techniques in photosynthesis (advances in photosynthesis and respiration), vol 3. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 75–92

Holzwarth AR, Müller MG, Niklas J, Lubitz W (2005) Charge recombination fluorescence in photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J Phys Chem B 109:5903–5911

Ihalainen JA, Rätsep M, Jensen PE, Scheller HV, Croce R, Bassi R, Korppi-Tommola JEI, Freiberg A (2003) Red spectral forms of chlorophylls in green plant PSI—a site-selective and high-pressure spectroscopy study. J Phys Chem B 107:9086–9093

Ihalainen JA, van Stokkum IHM, Gibasiewicz K, Germano M, van Grondelle R, Dekker JP (2005) Kinetics of excitation trapping in intact photosystem I of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Arabidopsis thaliana. BBA-Bioenergetics 1706:267–275

Jennings RC, Zucchelli G, Croce R, Garlaschi FM (2003) The photochemical trapping rate from red spectral states in PSI–LHCI is determined by thermal activation of energy transfer to bulk chlorophylls. BBA-Bioenergetics 1557:91–98

Jennings RC, Zucchelli G, Santabarbara S (2013) Photochemical trapping heterogeneity as a function of wavelength, in plant photosystem I (PSI–LHCI). BBA-Bioenergetics 1827:779–785

Jensen P, Haldrup A, Zhang S (2003) Molecular dissection of photosystem I in higher plants: topology, structure and function. Physiol Plant 119:313–321

Jia Y, DiMagno TD, Chan C, Wang Z, Du M, Hanson DK, Schiffer M, Norris JR, Fleming GR, Popov MS (1993) Primary charge separation in mutant reaction centers of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Phys Chem 97:13180–13191

Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt H, Klukas O, Saenger W, Krauss N (2001) Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature 411:909–919

Karapetyan NV, Schlodder E, van Grondelle R, Dekker JP (2006) The long wavelength chlorophylls of Photosystem I. In: Golbeck JH (ed) Photosystem I. The light-driven plastocyanin: ferredoxin oxidoreductase (advances in photosynthesis and respiration), vol 24. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 177–192

Kargul J, Nield J, Barber J (2003) Three-dimensional reconstruction of a light-harvesting complex I–photosystem I (LHCI–PSI) supercomplex form the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii—insights into light harvesting for PSI. J Biol Chem 278:16135–16141

Kirmaier C, Holten D (1990) Evidence that a distribution of bacterial reaction centers underlies the temperature and detection-wavelength dependence of the rates of the primary electron-transfer reactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:3552–3556

Li Y, van der Est A, Lucas MG, Ramesh VM, Gu F, Petrenko A, Lin S, Webber AN, Rappaport F, Redding K (2006) Directing electron transfer within photosystem I by breaking H-bonds in the cofactor branches. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:2144–2149

McConnell MD, Sun J, Siavashi R, Webber A, Redding KE, Golbeck JH, van der Est A (2015) Species-dependent alteration of electron transfer in the early stages of charge stabilization in photosystem I. BBA-Bioenergetics 1847:429–440

Melkozernov AN, Kargul J, Lin S, Barber J, Blankenship RE (2005) Spectral and kinetic analysis of the energy coupling in the PSI–LHCI supercomplex from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii at 77 K. Photosynth Res 86:203–215

Morosinotto T, Casteletti S, Breton J, Bassi R, Croce R (2002) Mutation analysis of Lhca1antenna complex—low energy absorption forms originate from pigment–pigment interactions. J Biol Chem 277:36253–36261

Mozzo M, Mantelli M, Passarini F, Caffarri S, Croce R, Bassi R (2010) Functional analysis of photosystem I light-harvesting complexes (Lhca) gene products of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. BBA-Bioenergetics 1797:212–221

Müller MG, Niklas J, Lubitz W, Holzwarth AR (2003) Ultrafast transient absorption studies on photosystem I reaction centers from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. 1. A new interpretation of the energy trapping and early electron transfer steps in photosystem I. Biophys J 85:3899–3922

Müller MG, Slavov C, Luthra R, Redding KE, Holzwarth AR (2010) Independent initiation of primary electron transfer in the two branches of the photosystem I reaction center. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:4123–4128

Novoderezhkin VI, Croce R, Wahadoszamen M, Polukhina I, Romero E, van Grondelle R (2016) Mixing of exciton and charge-transfer states. Phys Chem Chem Phys 18:19368–19377

Papageorgiou GC (2004) Fluorescence of photosynthetic pigments in vitro and in vivo. In: Papageorgiou GC, Govindjee (eds) Chlorophyll fluorescence: a signature of photosynthesis (advances in photosynthesis and respiration), vol 19. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 43–63

Parson WW (2007) Modern optical spectroscopy. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Ramesh VM, Webber AN (2004) Rapid isolation and purification of photosystem I chlorophyll-binding protein from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. In: Carpentier R (ed) Methods in molecular biology, vol 274. Humana Press Inc., New York, pp 19–28

Ramesh VM, Gibasiewicz K, Lin S, Bingham SE, Webber AN (2004) Bidirectional electron transfer in photosystem I: accumulation of A0 – in A-side or B-side mutants of the axial ligand to chlorophyll A0. Biochemistry 43:1369–1375

Ramesh VM, Gibasiewicz K, Lin S, Bingham SE, Webber AN (2007) Replacement of the methionine axial ligand to the primary electron acceptor A0 slows the A0 – reoxidation dynamics in photosystem I. BBA-Bioenergetics 1767:151–160

Rätsep M, Linnanto J, Freiberg A (2009) Mirror symmetry and vibrational structure in optical spectra of chlorophyll a. Journal Chem Phys 130:194501

Redding K, van der Est A (2006) The directionality of electron transfer in photosystem I. In: Golbeck JH (ed) Photosystem I. The light-driven plastocyanin: ferredoxin oxidoreductase (advances in photosynthesis and respiration), vol 24. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 413–437

Romero E, Mozzo M, van Stokkum IH, Dekker JP, van Grondelle R, Croce R (2009) The origin of the low-energy form of photosystem I light-harvesting complex Lhca4: mixing of the lowest exciton with a charge-transfer state. Biophys J 96:L35-7

Scheller HV, Jensen PE, Haldrup A, Lunde C, Knoetzel J (2001) Role of subunits in eukaryotic photosystem I. BBA-Bioenergetics 1507:41–60

Slavov C, Ballottari M, Morosinotto T, Bassi R, Holzwarth AR (2008) Trap-limited charge separation kinetics in higher plant photosystem I complexes. Biophys J 94:3601–3612

Slavov C, El-Mohsnawy E, Rögner M, Holzwarth AR (2009) Trapping kinetics in isolated cyanobacterial PS I complexes. Chem Phys 357:163–170

Snellenburg JJ, Laptenok S, Seger R, Mullen KM, van Stokkum IHM (2012) Glotaran: a Java-based graphical user interface for the R package TIMP. J Stat Softw 49:1–22

Snellenburg JJ, Dekker JP, van Grondelle R, van Stokkum IHM (2013) Functional compartmental modeling of the photosystems in the thylakoid membrane at 77 K. J Phys Chem B 117:11363–11371

Szewczyk S, Giera W, Białek R, Burdziński G, Gibasiewicz K (2017a) Acceleration of the excitation decay in photosystem I immobilized on glass surface. Photosynth Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-017-0454-z

Szewczyk S, Giera W, D’Haene S, van Grondelle R, Gibasiewicz K (2017b) Comparison of excitation energy transfer in cyanobacterial photosystem I in solution and immobilized on conducting glass. Photosynth Res 132:111–126

Van Amerongen H, van Grondelle R, Valkunas L (2000) Photosynthetic excitons. World Scientific, London

Van Stokkum IHM, Desquilbet TE, van der Weij-de Wit CD, Snellenburg JJ, van Grondelle R, Thomas JC, Dekker JP, Robert B (2013) Energy transfer and trapping in red-chlorophyll-free photosystem I from Synechococcus WH 7803. J Phys Chem B 117:11176–11183

Wientjes E, van Stokkum IHM, van Amerongen H, Croce R (2011) The role of the individual Lhcas in photosystem I excitation energy trapping. Biophys J 101:745–754

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from LASERLAB-EUROPE II: Grant Agreement No. 228334. R.v.G. acknowledges financial support from VU University Amsterdam, the Laserlab-Europe Consortium, the TOP Grant (700.58.305) from the Foundation of Chemical Sciences part of NWO, the advanced investigator Grant (267333, PHOTPROT) from the European Research Council, the EU FP7 Project PAPETS (GA 323901). R.v.G. gratefully acknowledges his Academy Professor grant from the Netherlands Royal Academy of Sciences (KNAW). K.R. acknowledges support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (Grant MCB-1052573). K.G. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Polish government (Scientific Project No. N N202 085440).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Giera, W., Szewczyk, S., McConnell, M.D. et al. Uphill energy transfer in photosystem I from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Time-resolved fluorescence measurements at 77 K. Photosynth Res 137, 321–335 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-018-0506-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11120-018-0506-z