Abstract

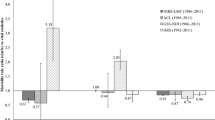

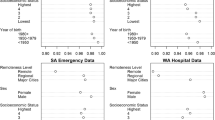

Mortality rates among black individuals exceed those of white individuals throughout much of the life course. The black–white disparity in mortality rates is widest in young adulthood, and then rates converge with increasing age until a crossover occurs at about age 85 years, after which black older adults exhibit a lower mortality rate relative to white older adults. Data quality issues in survey-linked mortality studies may hinder accurate estimation of this disparity and may even be responsible for the observed black–white mortality crossover, especially if the linkage of surveys to death records during mortality follow-up is less accurate for black older adults. This study assesses black–white differences in the linkage of the 1986–2009 National Health Interview Survey to the National Death Index through 2011 and the implications of racial/ethnic differences in record linkage for mortality disparity estimates. Match class and match score (i.e., indicators of linkage quality) differ by race/ethnicity, with black adults exhibiting less certain matches than white adults in all age groups. The magnitude of the black–white mortality disparity varies with alternative linkage scenarios, but convergence and crossover continue to be observed in each case. Beyond black–white differences in linkage quality, this study also identifies declines over time in linkage quality and even eligibility for linkage among all adults. Although linkage quality is lower among black adults than white adults, differential record linkage does not account for the black–white mortality crossover.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In supplemental analyses, I include a Year 2 term to determine whether match score decreases, reaches a minimum, and then increases over time, as is observed with linkage eligibility. The Year 2 term indicates a non-linear time trend, but with match score among decedents continuing to decline throughout the study period. Because the overall time trend does not change, I drop Year 2 from the model in favor of the more parsimonious model.

I subtract 18 from age so that the black main effect represents the relative black–white mortality disparity at age 18 years. The black-by-age intercept term and age coefficients do not change with relaxing and tightening because the cutoff scores are adjusted for black adults only. Respondents with relaxed cutoff scores who switch from survivors to deaths during follow-up are assigned 2011 (the final year of mortality follow-up) as their year of death.

References

Anderson, M. J., & Fienberg, S. E. (1999). Who counts? The politics of census-taking in contemporary America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Arias, E., Schauman, W. S., Eschbach, K., Sorlie, P. D., & Backlund, E. L. (2008). The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. Vital Health Stat, 2(148), 1–23.

Bates, N., Dahlhamer, J., & Singer, E. (2008). Privacy concerns, too busy, or just not interested: Using doorstep concerns to predict survey nonresponse. J Off Stat, 24(4), 591–612.

Brick, J. M., & Williams, D. (2013). Explaining rising nonresponse rates in cross-sectional surveys. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci, 645(1), 36–59.

Clogg, C. C., Petkova, E., & Haritou, A. (1995). Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. Am J Sociol, 100(5), 1261–1293.

Coale, A. J., & Kisker, E. E. (1986). Mortality crossovers: Reality or bad data? Popul Stud, 40(3), 389–401.

Curb, J. D., Ford, C. E., Pressel, S., Palmer, M., Babcock, C., & Hawkins, C. M. (1985). Ascertainment of vital status through the National Death Index and the Social Security Administration. Am J Epidemiol, 121(5), 754–766.

Dahlhamer, J. M., & Cox, C. S. (2007). Respondent consent to link survey data with administrative records: Results from a split-ballot field test with the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. In Proceedings of the federal committee on statistical methodology research conference. Washington, DC.

Dahlhamer, J. M., Meyer, P. S., & Pleis, J. R. (2006). Questions people don’t like to answer: Wealth and social security numbers. In Proceedings of the American Statistical Association Joint Statistical Meetings. Seattle, WA.

Data Linkage Team. (2015). Comparative analysis of the NHIS public-use and restricted-use linked mortality files: 2015 public-use data release. Hyattsville: National Center for Health Statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/nhis-public-restr-2011lmf-2-3-15.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2016.

Eberstein, I. W., Nam, C. B., & Heyman, K. M. (2008). Causes of death and mortality crossovers by race. Biodemogr Soc Biol, 54(2), 214–228.

Elo, I. T., Beltrán-Sánchez, H., & Macinko, J. (2014). The contribution of health care and other interventions to black–white disparities in life expectancy, 1980–2007. Popul Res Policy Rev, 33(1), 97–126.

Elo, I. T., & Preston, S. H. (1997). Racial and ethnic differences in mortality at older ages. In L. G. Martin & B. J. Soldo (Eds.), Racial and ethnic differences in the health of older Americans. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Fenelon, A. (2013). An examination of black/white differences in the rate of age-related mortality increase. Demogr Res, 29(17), 441–472.

Frisbie, W. P., Hummer, R. A., Powers, D. A., Song, S. E., & Pullum, S. G. (2010). Race/ethnicity/nativity differentials and changes in cause-specific infant deaths in the context of declining infant mortality in the US: 1989–2001. Popul Res Policy Rev, 29(3), 395–422.

Galea, S., & Tracy, M. (2007). Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol, 17(9), 643–653.

Harron, K., Goldstein, H., & Dibben, C. (Eds.). (2016). Methodological developments in data linkage. West Sussex: Wiley.

Harron, K., Wade, A., Muller-Pebody, B., Goldstein, H., & Gilbert, R. (2012). Opening the black box of record linkage. J Epidemiol Community Health, 66(12), 1198.

Hill, M. E., Preston, S. H., & Rosenwaike, I. (2000). Age reporting among white Americans aged 85+: results of a record linkage study. Demography, 37(2), 175–186.

Hogan, H., Cantwell, P. J., Devine, J., Mule, V. T., & Velkoff, V. (2013). Quality and the 2010 census. Popul Res Policy Rev, 32(5), 637–662.

Hummer, R. A. (1996). Black–white differences in health and mortality: A review and conceptual model. Sociol Q, 37(1), 105–125.

Jackson, J. S., Hudson, D., Kershaw, K., Mezuk, B., Rafferty, J., & Tuttle, K. K. (2011). Discrimination, chronic stress, and mortality among black Americans: A life course framework. In R. G. Rogers & E. M. Crimmins (Eds.), International handbook of adult mortality. New York: Springer.

Kestenbaum, B. (1992). A description of the extreme aged population based on improved medicare enrollment data. Demography, 29(4), 565–580.

Kochanek, K. D., Murphy, S. L., Xu, J., & Tejada-Vera, B. (2016). Deaths: Final data for 2014. Natl Vital Stat Rep, 65(4), 1.

Lariscy, J. T. (2011). Differential record linkage by Hispanic ethnicity and age in linked mortality studies: Implications for the epidemiologic paradox. J Aging Health, 23(8), 1263–1284.

Liao, Y., Cooper, R. S., Cao, G., Durazo-Arvizu, R., Kaufman, J. S., Luke, A., et al. (1998). Mortality patterns among adult Hispanics: Findings from the NHIS, 1986 to 1990. Am J Public Health, 88(2), 227–232.

Lynch, S. M., Brown, J. S., & Harmsen, K. G. (2003). Black–white differences in mortality compression and deceleration and the mortality crossover reconsidered. Res Aging, 25(5), 456–483.

Manton, K. G., & Stallard, E. (1981). Methods for evaluating the heterogeneity of aging processes in human populations using vital statistics data: Explaining the black/white mortality crossover by a model of mortality selection. Hum Biol, 53(1), 47–67.

Masters, R. K. (2012). Uncrossing the US black–white mortality crossover: The role of cohort forces in life course mortality risk. Demography, 49(3), 773–796.

Miller, E. A. (2012). What’s in a name? Accounting for naming conventions in NCHS data linkages. In Paper presented at the federal committee on statistical methodology (FCSM) statistical policy seminar, Washington, DC. http://www.copafs.org/UserFiles/file/seminars/2012FCSM/Session07FCSM2012Miller.pptx. Accessed 27 Feb 2013.

Miller, E. A., McCarty, F., & Parker, J. D. (2015). Differential linkage by race/ethnicity and availability of a social security number in the linkage with the national death index. In Paper presented at the National Conference on Health Statistics, Bethesda, MD. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ppt/nchs2015/Ingram_Tuesday_SalonD_BB1_2nd.pdf. Accessed 12 Nov 2015.

Nam, C. B. (1995). Another look at mortality crossovers. Soc Biol, 42(1–2), 133–142.

National Center for Health Statistics. (2009). NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study (NHEFS) calibration sample for NDI matching methodology. Hyattsville, MD. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/mort_calibration_study.pdf. Accessed 27 Sept 2013.

National Center for Health Statistics, Office of Analysis and Epidemiology. (2009). National health interview survey (1986–2004) linked mortality files, mortality follow-up through 2006: Matching methodology. Hyattsville, MD. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/matching_methodology_nhis_final.pdf. Accessed 3 Dec 2010.

National Center for Health Statistics, Office of Analysis and Epidemiology. (2013). NCHS 2011 linked mortality files matching methodology. Hyattsville, MD. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/datalinkage/2011_linked_mortality_file_matching_methodology.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr 2016.

National Research Council. (2013). Nonresponse in social science surveys: a research agenda. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Otten, M. W., Teutsch, S. M., Williamson, D. F., & Marks, J. S. (1990). The effect of known risk factors on the excess mortality of black adults in the United States. J Am Med Assoc, 263(6), 845–850.

Pettit, B. (2012). Invisible men: Mass incarceration and the myth of black progress. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Preston, S. H., Elo, I. T., Rosenwaike, M., & Hill, M. (1996). African–American mortality at older ages: Results of a matching study. Demography, 33(2), 193–209.

Preston, S. H., Elo, I. T., & Stewart, Q. (1999). Effects of age misreporting on mortality estimates at older ages. Popul Stud, 53(2), 165–177.

Preston, S. H., Hill, M. E., & Drevenstedt, G. L. (1998). Childhood conditions that predict survival to advanced ages among African–Americans. Soc Sci Med, 47(9), 1231–1246.

Research Triangle Institute. (2012). SUDAAN language manual, volumes 1 and 2, release 11.0. Research Triangle Park: Research Triangle Institute.

Robinson, J. G., West, K. K., & Adlakha, A. (2002). Coverage of the population in census 2000: Results from demographic analysis. Popul Res Policy Rev, 21(1–2), 19–38.

Rogers, R. G., Carrigan, J. A., & Kovar, M. G. (1997). Comparing mortality estimates based on different administrative records. Popul Res Policy Rev, 16(3), 213–224.

Rogers, R. G., Hummer, R. A., & Nam, C. B. (2000). Living and dying in the USA: Behavioral, health, and social differentials of adult mortality. San Diego: Academic Press.

Rosenberg, H. M., Maurer, J. D., Sorlie, P. D., Johnson, N. J., MacDorman, M. F., Hoyert, D. L., et al. (1999). Quality of death rates by race and Hispanic origin: A summary of current research, 1999. Vital Health Stat, 2(128), 1–3.

SAS Institute. (2011). The SAS system for windows. Release 9.2. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Satcher, D., Fryer, G. E., McCann, J., Troutman, A., Woolf, S. H., & Rust, G. (2005). What if we were equal? A comparison of the black–white mortality gap in 1960 and 2000. Health Aff, 24(2), 459–464.

Sorlie, P. D., Rogot, E., & Johnson, N. J. (1992). Validity of demographic characteristics on the death certificate. Epidemiology, 3(2), 181–184.

Wang, E. A., Aminawung, J. A., Wildeman, C., Ross, J. S., & Krumholz, H. M. (2014). High incarceration rates among black men enrolled in clinical studies may compromise ability to identify disparities. Health Aff, 33(5), 848–855.

Williams, D. R., & Sternthal, M. (2010). Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: Sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav, 51(1 suppl), S15–S27.

Acknowledgements

An earlier draft of this article was presented at the 2013 Southern Demographic Association meeting in Montgomery, Alabama. Research for this article was supported by training grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5 T32 HD007081) and the National Institute on Aging (5 T32 AG000139). Patricia Barnes, Jennifer Parker, and Donna Miller of the National Center for Health Statistics assisted in acquiring a special request file of the National Health Interview Survey Linked Mortality File data. Analyses were conducted in the Texas Federal Statistical Research Data Center (RDC) in College Station, Texas, Triangle RDC in Durham, North Carolina, and Missouri RDC in Columbia, Missouri. The research in this article was conducted while the author was a Special Sworn Status researcher of the U.S. Census Bureau at the Center for Economic Studies. Research results and conclusions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Census Bureau. This article has been screened to ensure that no confidential data are revealed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lariscy, J.T. Black–White Disparities in Adult Mortality: Implications of Differential Record Linkage for Understanding the Mortality Crossover. Popul Res Policy Rev 36, 137–156 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9415-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-016-9415-z