Abstract

Although evidence is increasing that climate shocks influence human migration, it is unclear exactly when people migrate after a climate shock. A climate shock might be followed by an immediate migration response. Alternatively, migration, as an adaptive strategy of last resort, might be delayed and employed only after available in situ (in-place) adaptive strategies are exhausted. In this paper, we explore the temporally lagged association between a climate shock and future migration. Using multilevel event-history models, we analyze the risk of Mexico-US migration over a seven-year period after a climate shock. Consistent with a delayed response pattern, we find that the risk of migration is low immediately after a climate shock and increases as households pursue and cycle through in situ adaptive strategies available to them. However, about 3 years after the climate shock, the risk of migration decreases, suggesting that households are eventually successful in adapting in situ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

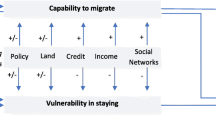

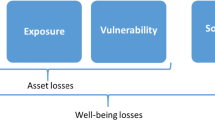

The socioeconomic context will also shape the directionality of the migration response (Black et al. 2011a). In a Latin American context, adverse climatic conditions often lead to an increase in international out-migration (Feng and Oppenheimer 2012; Gray and Bilsborrow 2013; Hunter et al. 2013). A decline in international migration has been observed in a few case studies of the African continent (Gray and Mueller 2012a; Henry et al. 2004). Under conditions of extreme poverty, households may become “trapped” in place when adverse environmental conditions undermine the resource base to finance a move (Black et al. 2011b).

The Mexican Migration Project (MMP) is a collaborative research project based at Princeton University and the University of Guadalajara. The MMP data are available at http://mmp.opr.princeton.edu.

The first international migration can be considered a major event that is remembered with reasonable accuracy by most household members. As such, use of the first migration has the added benefit of guarding against recall bias.

The phenomenon that households leave the dataset after the year they are surveyed is known in the event-history literature as “right censoring.” We retain right censored cases in the analysis based on the assumption that the censoring is non-informative, meaning that the time of migration is independent of the time a particular community was surveyed (Allison 1984; Steele 2005).

While this omission could bias our estimates, the amount of error is likely to be small in rural areas where migrants are more likely to return (Cornelius 1992; Riosmena 2004). In addition, when the permanent relocation of the entire household was related to climate impacts, then the resulting sample of households will be less sensitive to climate shocks. In this way, the presented results can be considered conservative and likely underestimate the magnitude of the true climate–migration response.

The expert team is jointly sponsored by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) Commission for Climatology (CCl), the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) project on Climate Variability and Predictability (CLIVAR), and the Joint WMO-Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Technical Commission for Oceanography and Marine Meteorology (JCOMM).

Inspection of density, overimputation, and overdispersion plots suggested accurate performance of the imputation model (Honaker et al. 2011).

Cokriging is based on regionalized variable theory (Matheron 1971) and uses the spatial trend and local spatial autocorrelation to inform predictions (Bolstad 2012; Hevesi et al. 1992). Cokriging has been frequently used to interpolate climate measures (e.g., Aznar et al. 2013; Garzon-Machado et al. 2014).

With a 1-kilometer grid cell resolution, the DEM is based on remotely sensed images from the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), created and released by the US Geological Survey (USGS) and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) (Danielson and Gesch 2011).

We tested the accuracy of the cokriging procedure by using a bootstrap split-sample method in which 10 % of the stations were omitted from the interpolation and error values were computed at known locations. The low magnitude of error values and random distribution across space suggests that the interpolations produced reliable results.

Unfortunately, measures of corn area harvested and percent irrigated farmland are only available for years after our study period. These variables were included to account for general differences in agricultural dependence and infrastructure availability. In our attempt to investigate changes in irrigation infrastructure, we were able to obtain a partial time series of the percent farmland irrigated for 25 of our 68 municipalities between 1994 and 2003. The average change in the proportion of farmland irrigated over this period was +0.003 % (SD = 7.27 %) and ranged from a minimum of −24.7 % to a maximum of +14.43 %. As such, the use of time-invariant measures to approximate historic conditions results in some uncertainty and the coefficient estimates should be interpreted with cautions.

Information on the percentage of adults with migration experience, the wealth index, and the percentage of male labor force employed in the agricultural sector was available at decadal time steps. For these measures, we employed linear interpolation to obtain semi-time-varying predictor, as recommended by the event-history literature (Allison 1984).

The year dummy variables account for unobserved changes, including policy changes, economic cycles, political events, technological advancements, and other climate shocks and natural disasters (Bohra-Mishra et al. 2014).

For increased speed and improved convergence properties, we used the integer scalar setting of nAGQ = 0 so that the random-effects and the fixed-effects coefficients were optimized (optimizer = “bobyqa”) in the penalized iteratively reweighted least squares step (Bates et al. 2014).

“Appendix 2” reports a correlation matrix (Table 4) as well as the parameter estimates for household and municipality control variables (Table 5) included in the fully adjusted multilevel event-history model.

We observed similar results for various other ETCCDI indices, including the % warm days (tx90p), the number of frost days (fd), the temperature during the coldest day (txn), the % cool nights (tn10p), and the total wet-day precipitation (prcptot). Results from different measures serve as a robustness test, suggesting that the reported functional form reflects a general pattern.

The coefficients for “No. days heavy precip” reflects the effect of a one standard deviation decrease in precipitation.

References

Abu, M., Codjoe, S. N. A., & Sward, J. (2014). Climate change and internal migration intentions in the forest-savannah transition zone of Ghana. Population and Environment, 35(4), 341–364. doi:10.1007/s11111-013-0191-y.

Adger, W. N., Dessai, S., Goulden, M., Hulme, M., Lorenzoni, I., Nelson, D. R., & Wreford, A. (2009). Are there social limits to adaptation to climate change? Climatic Change, 93(3–4), 335–354. doi:10.1007/s10584-008-9520-z.

Alexander, L. V., Zhang, X., Peterson, T. C., Caesar, J., Gleason, B., Tank, A., & Vazquez-Aguirre, J. L. (2006). Global observed changes in daily climate extremes of temperature and precipitation. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 111(D5), 22. doi:10.1029/2005jd006290.

Allison, P. D. (1984). Event history analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Angelucci, M. (2012). U.S. border enforcement and the net flow of Mexican illegal migration. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 60(2), 311–357.

Auffhammer, M., Hsiang, S. M., Schlenker, W., & Sobel, A. (2013). Using weather data and climate model output in economic analyses of climate change. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 7(2), 181–198. doi:10.1093/reep/ret016.

Aznar, J. C., Gloaguen, E., Tapsoba, D., Hachem, S., Caya, D., & Begin, Y. (2013). Interpolation of monthly mean temperatures using cokriging in spherical coordinates. International Journal of Climatology, 33(3), 758–769. doi:10.1002/joc.3468.

Barber, J. S., Murphy, S. A., Axinn, W. G., & Maples, J. (2000). Discrete-time multilevel hazard analysis. Sociological Methodology, 30(1), 201–235.

Bardsley, D. K., & Hugo, G. J. (2010). Migration and climate change: examining thresholds of change to guide effective adaptation decision-making. Population and Environment, 32(2–3), 238–262. doi:10.1007/s11111-010-0126-9.

Bates, D. M. (2010). lme4: Mixed-effects modeling with R. New York: Springer.

Bates, D. M., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. M., & Walker, S. (2014). lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. Vienna, Austria: CRAN.R-project.org.

Berkes, F., & Jolly, D. (2002). Adapting to climate change: Socialecological resilience in a Canadian western arctic community. Conservation Ecology, 5(2), 1–15.

Black, R., Adger, W. N., Arnell, N. W., Dercon, S., Geddes, A., & Thomas, D. S. (2011a). The effect of environmental change on human migration. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 21, S3–S11. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.10.001.

Black, R., Arnell, N. W., Adger, W. N., Thomas, D., & Geddes, A. (2013). Migration, immobility and displacement outcomes following extreme events. Environmental Science & Policy, 27, S32–S43. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2012.09.001.

Black, R., Bennett, S. R. G., Thomas, S. M., & Beddington, J. R. (2011b). Migration as adaptation. Nature, 478(7370), 447–449.

Bohra-Mishra, P., Oppenheimer, M., & Hsiang, S. M. (2014). Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(27), 9780–9785. doi:10.1073/pnas.1317166111.

Bolstad, P. (2012). GIS fundamentals: A first text on geographic information systems (4th ed.). White Bear Lake, MN: Eider Press.

Boyd, R., & Ibarraran, M. E. (2009). Extreme climate events and adaptation: an exploratory analysis of drought in Mexico. Environment and Development Economics, 14, 371–395. doi:10.1017/s1355770x08004956.

Bronaugh, D. (2014). R package climdex pcic: PCIC implementation of Climdex routines. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Pacific Climate Impact Consortium.

Brown, S. K., & Bean, F. D. (2006). International Migration. In D. Posten & M. Micklin (Eds.), Handbook of population (pp. 347–382). New York: Springer Publishers.

Bylander, M. (2013). Depending on the sky: Environmental distress, migration, and coping in rural Cambodia. International Migration, 53(5), 135–147. doi:10.1111/imig.12087.

Caesar, J., Alexander, L., & Vose, R. (2006). Large-scale changes in observed daily maximum and minimum temperatures: Creation and analysis of a new gridded data set. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 111(D5), 1–10. doi:10.1029/2005JD006280.

Cakir, R. (2004). Effect of water stress at different development stages on vegetative and reproductive growth of corn. Field Crops Research, 89(1), 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2004.01.005.

Calavita, K. (1992). Inside the state: The bracero program, immigration, and the I.N.S.. New York: Routledge.

Carney, D., Drinkwater, M., Rusinow, T., Neefjes, K., Wanmali, S., & Singh, N. (1999). Livelihoods approaches compared. London: Department for International Development.

Carr, D. L., Lopez, A. C., & Bilsborrow, R. E. (2009). The population, agriculture, and environment nexus in Latin America: country-level evidence from the latter half of the twentieth century. Population and Environment, 30(6), 222–246. doi:10.1007/s11111-009-0090-4.

Christensen, J. H., Krishna Kumar, K., Aldrian, E., An, S. I., Cavalcanti, I. F. A., de Castro, M., & Zhou, T. (2013). Climate phenomena and their relevance for future regional climate change. In T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G. K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Climate change 2013: The physical science basis: Contribution of Working Group 1 to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, J. H. (2004). The culture of migration in Southern Mexico. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Collins, M., Knutti, R., Arblaster, J., Dufresne, J. L., Fichefet, T., Friedlingstein, P., & Wehner, M. (2013). Long-term climate change: Projections, commitments and irreversibility. In T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G. K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Climate change 2013: The physical science basis: Contribution of working group 1 to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Conde, C., Ferrer, R., & Orozco, S. (2006). Climate chage and climate variability impacts on rainfed agricultural activities and possible adaptation measures. A Mexico case study. Atmosfera, 19(3), 181–194.

Cornelius, W. A. (1992). From sojourners to settlers: The changing profile of Mexican migration to the United States. In J. A. Bustamante, C. W. Reynolds, & R. A. Hinojosa Ojeda (Eds.), U.S.-Mexico relations: Labor market interdependence (pp. 155–195). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Danielson, J. J., & Gesch, D. B. (2011). Global multi-resolution terrain elevation data 2010 (GMTED2010): Open-File Report 2011-1073. Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey.

de Haas, H. (2011). Mediterranean migration futures: Patterns, drivers and scenarios. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 21, S59–S69. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.003.

de Janvry, A., & Sadoulet, E. (2001). Income strategies among rural households in Mexico: The role of off-farm activities. World Development, 29(3), 467–480.

Dow, K., Berkhout, F., Preston, B. L., Klein, R. J. T., Midgley, G., & Shaw, M. R. (2013). Commentary: Limits to adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 3(4), 305–307.

Durand, J., & Arias, P. (2000). La experiencia migrante: Iconografia de la migracion Mexico-Estados Unidos. Xalapa, Mexico: Altexto.

Durand, J., Parrado, E. A., & Massey, D. S. (1996). Migradollars and development: A reconsideration of the Mexican case. International Migration Review, 30(2), 423–444. doi:10.2307/2547388.

Endfield, G. H. (2007). Archival explorations of climate variability and social vulnerability in colonial Mexico. Climatic Change, 83(1–2), 9–38. doi:10.1007/s10584-006-9125-3.

Feng, S., & Oppenheimer, M. (2012). Applying statistical models to the climate-migration relationship. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 109(43), E2915.

Findlay, A. M. (2011). Migrant destinations in an era of environmental change. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 21, S50–S58. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.09.004.

Fischer, P. A., & Malmberg, G. (2001). Settled people don’t move: On life course and (im-)mobility in Sweden. International Journal of Population Geography, 7, 357–371.

Fussell, E. (2004). Sources of Mexico’s migration stream: Rural, urban, and border migrants to the United States. Social Forces, 82(3), 937–967. doi:10.1353/sof.2004.0039.

Fussell, E., & Massey, D. S. (2004). The limits to cumulative causation: International migration from Mexican urban areas. Demography, 41(1), 151–171.

Garzon-Machado, V., Otto, R., & Aguilar, M. J. D. (2014). Bioclimatic and vegetation mapping of a topographically complex oceanic island applying different interpolation techniques. International Journal of Biometeorology, 58(5), 887–899. doi:10.1007/s00484-013-0670-y.

Gray, C. L. (2009). Environment, land, and rural out-migration in the Southern Ecuadorian Andes. World Development, 37(2), 457–468. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.05.004.

Gray, C. L. (2010). Gender, natural capital, and migration in the southern Ecuadorian Andes. Environment and Planning, 42, 678–696.

Gray, C. L., & Bilsborrow, R. (2013). Environmental influences on human migration in rural ecuador. Demography, 50, 1217–1241. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0192-y.

Gray, C. L., & Mueller, V. (2012a). Drought and population mobility in rural Ethiopia. World Development, 40(1), 134–145. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.023.

Gray, C. L., & Mueller, V. (2012b). Natural disasters and population mobility in Bangladesh. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(16), 6000–6005. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115944109.

Hamilton, E. R., & Villarreal, A. (2011). Development and the urban and rural geography of Mexican emigration to the United States. Social Forces, 90(2), 661–683. doi:10.1093/sf/sor011.

Henry, S., Schoumaker, B., & Beauchemin, C. (2004). The impact of rainfall on the first out-migration: A multi-level event-history analysis in Burkina Faso. Population and Environment, 25(5), 423–460.

Hevesi, J. A., Istok, J. D., & Flint, A. L. (1992). Precipitation estimation in mountainous terrain using multivariate geostatistics. 1. Structural-analysis. Journal of Applied Meteorology, 31(7), 661–676. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1992)031<0661:peimtu>2.0.co;2.

Honaker, J., & King, G. (2010). What to do about missing values in time-series cross-section data. American Journal of Political Science, 54(2), 561–581.

Honaker, J., King, G., & Blackwell, M. (2011). Amelia II: A program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(7), 1–47.

Howden, S. M., Soussana, J.-F., Tubiello, F. N., Chhetri, N., Dunlop, M., & Meinke, H. (2007). Adapting agriculture to climate change. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(50), 19691–19696. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701890104.

Hunter, L. M., Luna, J. K., & Norton, R. M. (2015). Environmental dimensions of migration. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 377–397. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112223.

Hunter, L. M., Murray, S., & Riosmena, F. (2013). Rainfall patterns and U.S. migration from rural Mexico. International Migration Review, 47(4), 874–909.

Hunter, L. M., Nawrotzki, R. J., Leyk, S., Maclaurin, G. J., Twine, W., Collinson, M., & Erasmus, B. (2014). Rural outmigration, natural capital, and livelihoods in South Africa. Population, Space, and Place, 20, 402–420. doi:10.1002/psp.1776.

INEGI. (2012). Sistema Estatal y Municipal de Bases de Datos. Aguascalientes, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática.

IPCC. (2012). In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, G. K. Plattner, S. K. Allen, M. Tignor, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation: A special report of working groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

IPCC. (2013). Summary for Policymakers. In T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G. K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Climate change 2013: The physical science basis: Contribution of Working Group 1 to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 1–30). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Kanaiaupuni, S. M. (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces, 78(4), 1311–1347. doi:10.2307/3006176.

Kandel, W., & Massey, D. S. (2002). The culture of Mexican migration: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Social Forces, 80(3), 981–1004. doi:10.1353/sof.2002.0009.

Keleman, A., Hellin, J., & Bellon, M. R. (2009). Maize diversity, rural development policy, and farmers’ practices: lessons from Chiapas, Mexico. Geographical Journal, 175, 52–70. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2008.00314.x.

Klein Tank, A. M. G., Peterson, T. C., Quadir, D. A., Dorji, S., Zou, X., Tang, H., & Spektorman, T. (2006). Changes in daily temperature and precipitation extremes in central and south Asia. Journal of Geophysical Research-Atmospheres, 111(D16), 1–8. doi:10.1029/2005jd006316.

Kugler, T. A., Van Riper, D. C., Manson, S. M., Haynes, D. A., Donato, J., & Stinebaugh, K. (2015). Terra Populus: Workflows for integrating and harmonizing geospatial population and environmental data. Journal of Map and Geography Libraries, 11(2), 180–206. doi:10.1080/15420353.2015.1036484.

Lindstrom, D. P., & Lauster, N. (2001). Local economic opportunity and the competing risks of internal and US migration in Zacatecas. Mexico. International Migration Review, 35(4), 1232–1256.

Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data (2nd (edition ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Lobell, D. B., & Field, C. B. (2007). Global scale climate - crop yield relationships and the impacts of recent warming. Environmental Research Letters, 2(1), 1–7. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/2/1/014002.

LoBreglio, K. (2004). The border security and immigration improvement act a modern solution to a historic problem. St. John’s Law Review, 78(3), 933–963.

Luers, A. L., Lobell, D. B., Sklar, L. S., Addams, C. L., & Matson, P. A. (2003). A method for quantifying vulnerability, applied to the agricultural system of the Yaqui Valley, Mexico. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, 13(4), 255–267. doi:10.1016/s0959-3780(03)00054-2.

Lustig, N. (1990). Economic-crisis, adjustment and living standards in Mexico, 1982-85. World Development, 18(10), 1325–1342. doi:10.1016/0305-750x(90)90113-c.

Marra, M., Pannell, D. J., & Ghadim, A. A. (2003). The economics of risk, uncertainty and learning in the adoption of new agricultural technologies: where are we on the learning curve? Agricultural Systems, 75(2–3), 215–234. doi:10.1016/s0308-521x(02)00066-5.

Martin, P. L. (1990). Harvest of confusion: Immigration reform and California agriculture. International Migration Review, 24(1), 69–95. doi:10.2307/2546672.

Massey, D. S. (1987). The Ethnosurvey in theory and practice. International Migration Review, 21(4), 1498–1522. doi:10.2307/2546522.

Massey, D. S., Alarcon, R., Durand, J., & Gonzalez, H. (1987). Return to Aztlan: The social process of international migration from Western Mexico. Berkely, CA: University of California Press.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration—A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, E. J. (1998). Worlds in motion: Understanding international migration at the end of the millennium. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Massey, D. S., & Capoferro, C. (2004). Measuring undocumented migration. International Migration Review, 38(3), 1075–1102.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Publications.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Pren, K. A. (2015). Border enforcement and return migration by documented and undocumented Mexicans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(7), 1015–1040. doi:10.1080/1369183x.2014.986079.

Massey, D. S., & Espinosa, K. E. (1997). What’s driving Mexico-US migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. American Journal of Sociology, 102(4), 939–999. doi:10.1086/231037.

Massey, D. S., Goldring, L., & Durand, J. (1994). Continuities in transnational migration: An analysis of nineteen Mexican communities. American Journal of Sociology, 99(6), 1492–1533.

Massey, D. S., & Parrado, E. A. (1998). International migration and business formation in Mexico. Social Science Quarterly, 79(1), 1–20.

Massey, D. S., & Riosmena, F. (2010). Undocumented migration from Latin America in an era of rising U.S. enforcement. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630, 294–321.

Massey, D. S., & Zenteno, R. (2000). A validation of the ethnosurvey: The case of Mexico-US migration. International Migration Review, 34(3), 766–793. doi:10.2307/2675944.

Matheron, G. (1971). The theory of regionalized variables and its applications. Paris, France: Ecole Nationale Superieur des Mines de Paris.

Mberu, B. U. (2006). Internal migration and household living conditions in Ethiopia. Demographic Research, 14, 509–539. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2006.14.21.

McKenzie, D. J. (2006). The consumer response to the Mexican peso crisis. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55(1), 139–172. doi:10.1086/505721.

McLeman, R. A. (2011). Settlement abandonment in the context of global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 21, S108–S120.

McLeman, R. A. (2014). Climate and human migration: Past experiences, future challenges. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Menne, M. J., Durre, I., Vose, R. S., Gleason, B. E., & Houston, T. G. (2012). An overview of the global historical climatology network-daily database. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 29(7), 897–910. doi:10.1175/jtech-d-11-00103.1.

Montgomery, M. R., Gragnolati, M., Burke, K. A., & Paredes, E. (2000). Measuring living standards with proxy variables. Demography, 37(2), 155–174.

MPC. (2013a). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.2 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

MPC. (2013b). Terra Populus: Beta Version [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota.

Mueller, V., Gray, C. L., & Kosec, K. (2014). Heat stress increases long-term human migration in rural Pakistan. Nature Climate Change, 4(3), 182–185. doi:10.1038/nclimate2103.

Nawrotzki, R. J. (2012). The politics of environmental concern: A cross-national analysis. Organization & Environment, 25(3), 286–307. doi:10.1177/1086026612456535.

Nawrotzki, R. J., Hunter, L. M., Runfola, D. M., & Riosmena, F. (2015a). Climate change as migration driver from rural and urban Mexico. Environmental Research Letters, 10(11), 114023. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/11/114023.

Nawrotzki, R. J., Riosmena, F., & Hunter, L. M. (2013). Do rainfall deficits predict U.S.-bound migration from rural Mexico? Evidence from the Mexican census. Population Research and Policy Review, 32(1), 129–158. doi:10.1007/s11113-012-9251-8.

Nawrotzki, R. J., Riosmena, F., Hunter, L. M., & Runfola, D. M. (2015b). Amplification or suppression: Social networks and the climate change-migration association in rural Mexico. Global Environmental Change, 35, 463–474. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.002.

Orrenius, P. M., & Zavodny, M. (2003). Do amnesty programs reduce undocumented immigration? Evidence from IRCA Demography, 40(3), 437–450. doi:10.2307/1515154.

Osbahr, H., Twyman, C., Adger, W. N., & Thomas, D. S. G. (2008). Effective livelihood adaptation to climate change disturbance: Scale dimensions of practice in Mozambique. Geoforum, 39(6), 1951–1964. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.07.010.

Peterson, T. C., Folland, C., Gruza, G., Hogg, W., Mokssit, A., & Plummer, N. (2001). Report of the activities of the working group on climate change detection and related rapporteurs. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization.

Peterson, T. C., & Manton, M. J. (2008). Monitoring changes in climate extremes—A tale of international collaboration. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 89(9), 1266–1271. doi:10.1175/2008bams2501.1.

RCoreTeam. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Riosmena, F. (2004). Return Versus Settlement Among Undocumented Mexican Migrants, 1980 to 1996. In J. Durand & D. S. Massey (Eds.), Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican migration project (pp. 265–280). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Riosmena, F. (2009). Socioeconomic context and the association between marriage and Mexico-US migration. Social Science Research, 38(2), 324–337. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.12.001.

Rubin, D. (1987). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley.

Ruggles, S., King, M. L., Levison, D., McCaa, R., & Sobek, M. (2003). IPUMS-international. Historical Methods, 36(2), 60–65.

Ruiter, S., & De Graaf, N. D. (2006). National context, religiosity, and volunteering: Results from 53 countries. American Sociological Review, 71(2), 191–210.

Saldana-Zorrilla, S. O., & Sandberg, K. (2009). Spatial econometric model of natural disaster impacts on human migration in vulnerable regions of Mexico. Disasters, 33(4), 591–607. doi:10.1111/j.0361-3666.2008.01089.x.

Schroth, G., Laderach, P., Dempewolf, J., Philpott, S., Haggar, J., Eakin, H., & Ramirez-Villegas, J. (2009). Towards a climate change adaptation strategy for coffee communities and ecosystems in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, Mexico. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 14(7), 605–625. doi:10.1007/s11027-009-9186-5.

Scoones, I. (1999). Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Brighton, U.K.: Institute of Development Studies.

Singer, J. D., & Willett, J. B. (2003). Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stahle, D. W., Cook, E. R., Villanueva Diaz, J., Fye, F. K., Burnette, D. J., Griffin, R. D., & Heim, R. R. (2009). Early 21st-Century drought in Mexico. EOS Transactions of the American Geographical Union, 90(11), 89–100.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178.

Steele, F. (2005). Event history analysis. Bristol, U.K.: ESRC National Centre for Research Methods.

Steele, F., Diamond, I., & Amin, S. (1996). Immunization uptake in rural Bangladesh: A multilevel analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series a-Statistics in Society, 159, 289–299. doi:10.2307/2983175.

Steele, F., Goldstein, H., & Browne, W. (2004). A general multilevel multistate competing risks model for event history data, with an application to a study of contraceptive use dynamics. Statistical Modelling, 4(2), 145–159. doi:10.1191/1471082X04st069oa.

Taylor, J. E. (1999). The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1), 63–88.

Warner, K., & van der Geest, K. (2013). Loss and damage from climate change: local-level evidence from nine vulnerable countries. International Journal of Global Warming, 5(4), 367–386. doi:10.1504/ijgw.2013.057289.

Wehner, M., Easterling, D. R., Lawrimore, J. H., Heim, R. R, Jr, Vose, R. S., & Santer, B. D. (2011). Projections of future drought in the continental United States and Mexico. Journal of Hydrometeorology, 12(6), 1359–1377. doi:10.1175/2011jhm1351.1.

Wiggins, S., Keilbach, N., Preibisch, K., Proctor, S., Herrejon, G. R., & Munoz, G. R. (2002). Discussion—Agricultural policy reform and rural livelihoods in central Mexico. Journal of Development Studies, 38(4), 179–202. doi:10.1080/00220380412331322461.

Williams, N. (2015). Temporal dimensions of weather shocks. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the Population Association of America, San Diego, CA.

Winters, P., Davis, B., & Corral, L. (2002). Assets, activities and income generation in rural Mexico: factoring in social and public capital. Agricultural Economics, 27(2), 139–156.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by NIH center Grants #R24 HD041023 awarded to the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota and #R24 HD066613 awarded to the Colorado Population Center at the University of Colorado-Boulder by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). In addition, this work received support from the National Science Foundation funded Terra Populus project (NSF Award ACI-0940818). We thank Rachel Magennis for her careful editing and helpful suggestions. We express our gratitude to the POEN editor and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Definition of climate measures

Warm spell duration index (wsdi): The warm spell duration index is defined as the annual count of days when at least six consecutive days surpassed the 90th percentile of the maximum temperature of the baseline period (1961–1990). Let TX ij be the daily maximum temperature on day i in period j and let TX in 90 be the calendar day 90th percentile centered on a 5-day window for the base period 1961–1990. The warm spell duration can then be computed as the period specific count of days N j with at least 6 consecutive days where TX ij > TX in 90 (Eq. 2).

No. days heavy precip (r10mm ): The no. of days of heavy precipitation is defined as the annual count of days with more than 10 mm of precipitation. Let RR ij be the daily precipitation amount on day i in period j. The number of days with heavy precipitation is then computed as the count of days N where RR ij ≥ 10 mm (Eq. 3).

For a full list of ETCCDI indices and their technical definitions, see http://etccdi.pacificclimate.org/list_27_indices.shtml.

Appendix 2: Correlation matrix and parameter estimates of control variables

Table 4 provides a matrix of correlations of outcome and substantive predictor variables employed in the investigation of the timing of international migration in response to climate shocks from rural Mexico during 1986–1999.

The decision to migrate is influenced by various socio-demographic factors (Brown and Bean 2006). Table 5 shows multilevel event-history models, including only household-level variables (Model 1), and then adding municipality-level predictors (Model 2). In line with much prior work on Mexican migration, the models suggest that the typical migrant household is male-headed (Lindstrom and Lauster 2001), has few young children (Massey and Riosmena 2010; Nawrotzki et al. 2013), is employed in a blue-collar occupation with limited work experience (Fussell 2004; Massey et al. 1987), and does not own property or a business (cf., Massey and Parrado 1998). Only a few municipality characteristics influence the probability to migrate. The probability to migrate is strongly elevated for communities with large proportions of adults with prior international migration experience, testifying to the importance of social networks (Fussell 2004; Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey et al. 1994). In addition, households are less likely to migrate from areas with historically warm temperatures, which likely reflects that most migrants come from the cooler west-central parts of Mexico, instead of the hot arid northern border states (Hamilton and Villarreal 2011).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nawrotzki, R.J., DeWaard, J. Climate shocks and the timing of migration from Mexico. Popul Environ 38, 72–100 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-016-0255-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11111-016-0255-x