Abstract

Americans of all political stripes abstractly support most of the rights and liberties guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, such as free expression. Yet, we argue that attitudes regarding the basic mechanics of civil liberties—e.g., from whom they are protections—are divided across partisan lines. Because of elite rhetoric, we hypothesize that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to perceive rights violations, often by non-government entities (generally incapable of violations), and that they will perceive rights as under threat with greater frequency. Using a survey containing unique questions about rights, we first demonstrate that a large majority of the mass public has fixed preference structures regarding rights, suggesting that attitudes about liberties are not merely error-ridden, top-of-the-head assessments. These preference structures differ for Democrats and Republicans. Next, we find support for our theory that attitudes regarding rights, from whom they are protective, and their level of protectiveness are asymmetric across partisanship. Beyond implications for citizens’ democratic capacities, our results also highlight potential concerns about the influence of partisan bias in demands on leaders regarding rights protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

In a 2021 report, a Knight Foundation–Ipsos study found that Americans overwhelmingly support free speech, regardless of party, race, or other characteristics that typically divide opinions on political matters.Footnote 1 Yet, there are great partisan differences in the types of expression that are viewed as legitimately protected by the First Amendment; the 2020 protests regarding racial justice are viewed as legitimate by those on the political left and protests regarding alleged election fraud in 2020 are viewed as legitimate by those on the right. This distinction—between abstract support for civil liberties and specific support for expressions thereof—appears frequently in the scholarly literature on rights and liberties (e.g., Chong, 1993; Gibson, 2013), though the major focus tends to be on the tolerance of objectionable behaviors ostensibly protected by the constitution (also see Nelson et al., 1997). As Strother and Bennett (2021) write, “scholars have spent far more time seeking to understand tolerance than civil liberties attitudes”. The focus on tolerance has left open normatively important questions regarding heterogeneity across political lines in the support of constitutional guarantees. More than mere partisan differences in attitudes, support driven by political predispositions indicates rights preferences may be subject to top-down manipulation and, ultimately, to more political caprice than intended.Footnote 2 This is particularly concerning in light of evidence that elites use “rights talk” in strategic ways (Glendon, 1991).

In this paper, we investigate the partisan contours of mass attitudes toward civil rights and liberties. Beyond consideration of attitudes regarding individual rights, we are concerned with the understanding of the basic mechanics of civil liberties, such as recognition of from whom constitutional guarantees are a protection. We propose that there are distinct partisan differences in the liberties that are preferred, in perceptions of who violates rights, and the trajectory of rights. This is in spite of wide scale agreement on several rights, which may mask important differences in support of civil liberties. For example, polling data indicate that both Republicans and Democrats support free speech. There is also bipartisan agreement on restricting access to gunsFootnote 3; major differences on Second Amendment preferences involve gun-ownership (or lack thereof) more so than partisanship. Likewise, most Americans support legal abortions.Footnote 4 Thus, we ask whether considerations of partisanship are confined to questions of tolerance with respect to rights and liberties—do predispositions underlie attitudes regarding rights, or only attitudes regarding the tolerance of the exercise of rights? Moreover, do predispositions underlie understanding of the rights guaranteed by the constitution and from whom they protect citizens?

To answer these questions, we utilize a survey that contains many unique questions tapping perceptions of rights and liberties. Our first goal is to establish whether the mass public appears to possess meaningful preferences about rights and liberties. While a great deal of research asks about rights attitudes, several studies indicate that these attitudes are malleable, contextual, and subject to change based on the relevant frame or cue (e.g., Chong, 1993; Nelson et al., 1997; Strother & Bennett, 2021). Given Americans’ notoriously low levels of ideological constraint and knowledge of politics, it is possible that rights and liberties attitudes are not particularly deep-seated. As such, we are interested in the structure of preferences regarding rights, as well as whether there are distinct structures across political lines. We use the method of triads to determine whether rights preference structures exist and, if so, whether they are systematically related to partisan identification. Upon identifying meaningful, fixed preference structures regarding rights, we then ask about partisan differences in the perceptions of rights violations and threats to rights. Existing scholarship has identified that Americans, generally, struggle to identify the outer limits of liberties and their protections (e.g., Greene, 2021; Persily et al., 2008). We believe there is good reason to expect differences in these perceptions and attitudes, given the rights that party leaders tend to highlight (e.g., the right to bear arms among right-wing politicians; see, for instance, Lewis, 2017).

Our results support the hypothesis that there are both heterogeneous views on rights and heterogeneous rights preference structures, though results are nuanced. We find that there is some agreement on the importance of various rights—Democrats and Republicans alike rank free speech as the most important constitutional guarantee—but conflicting preferences do exist and are driven substantially by partisanship. Despite the fact that Americans largely agree on the importance of fundamental liberties, there is relative disagreement on which rights are more (or less) important than others. Additionally, perceptions of violations of and threats toward many rights are partisan in nature. For example, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to state that non-governmental entities such as media outlets have violated their rightsFootnote 5 and that rights of all types are under threat (e.g., to bear arms, privacy).

These findings have important implications for understanding political disagreement regarding the exercise of rights and liberties beyond which group is exercising their rights. That is, beyond well-established differences in the tolerance of liberties, differences across political lines exist in basic attitudes about liberties. While support for legal norms and democratic principles once underwrote civil liberties attitudes (see Chong, 1993), we find that liberties attitudes seem to have polarized along with many other facets of contemporary political life in the United States. By the nature of being enshrined in the constitution, civil liberties are intended to be guarantees free from political whims. Yet, the public’s views on rights and liberties appear to be guided, at least partially, by deep-seated political predispositions, opening the door to partisan bias in supporting certain rights. Support for rights and liberties rooted in identity-laden attachments may mean our constitutional guarantees are less secure than is commonly believed.

Civil Liberties Attitudes

Given the centrality of rights and liberties to the American political ethos, much scholarship investigates the mass public’s position toward specific liberties (e.g., Combs & Welch, 1982; Erskine, 1970), tolerance of the exercise thereof (Marcus et al., 1995; Strother & Bennett, 2021; Sullivan et al., 1981), general pro-civil liberties attitudes (Gibson, 2013), and the trade-offs between liberty and security (Davis & Silver, 2004; Sullivan & Hendriks, 2009). Moreover, both individual-level factors—like religion (Fowler et al., 2018)—and external factors—like media coverage and framing (Nelson et al., 1997; Scheufele et al., 2005)—can play a role in shaping liberties attitudes. These studies offer useful insights into how individuals reach conclusions about rights and liberties, as well as their general orientations toward constitutional guarantees. However, there seems to be a major disconnect between the basic mechanics of rights and attitudes toward rights. For starters, the literature on tolerance identifies large gaps in support for rights relative to the exercise of rights by unpopular groups (Gibson, 2013; Strother & Bennett, 2021). For instance, individuals support free speech but are willing to curtail it for speech they dislike. That is, they are willing to employ the very mechanism from which free expression is protective (i.e., government intervention), indicating that support for the right is only nominal.

The same is true of other rights, like gun and property rights (Strother & Bennett, 2021). Further, as Chong (1993) indicates, many are willing to defend what they perceive to be constitutional rights “even if they did not fully understand either the scope or justification of that right” (869). Finally, there are wide gaps between the public’s understanding of some constitutional issues and the Supreme Court’s understanding of those issues (Persily et al., 2008).

Given that the mythos of constitutional rights and liberties appears to be distinct from the genuine understanding of what rights Americans possess and to what those rights entitle them, we are first interested in determining whether individuals possess genuine preferences regarding rights. Inasmuch as many speak about rights only to “say what they understand to be socially desirable” but also “believe it for the same reason” (Chong, 1993, p. 869), rights attitudes may be largely error-ridden, random, or top-of-the-head statements. We seek to determine if this is the case. On the one hand, research on the democratic capabilities of the mass public indicate we should not expect fixed preferences. Americans tend to lack political knowledge (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996) and are not particularly ideologically constrained (Lupton et al., 2015). On the other hand, individuals do fare better when considering abstract objects central to political conflict, like values (Jacoby, 2006). In addition, the specific type of knowledge one possesses matters, meaning there is some danger in making inferences about the effect of one type of knowledge given information about another (Barabas et al., 2014). Indeed, as Gilens (2001) writes, “…many people who are fully informed in terms of general political knowledge are nonetheless ignorant of policy specific information that would alter their political judgments” (380). The same very well may be true of knowledge about rights (or the lack thereof). As a result of these conflicting accounts, we do not form expectations regarding whether, or how many, individuals have firm rights preferences. However, we do expect that Democrats and Republicans will have different preference orderings (should firm preferences exist). Republicans, for instance, are more likely to support the right to bear arms than Democrats. Additionally, this (partially) exploratory portion of this paper gives way to expectations regarding partisan heterogeneity in other core elements of constitutional rights, such as meaningful understanding of from whom civil liberties are protective.

Stated differently, we focus on investigating mass attitudes with respect to the basic mechanics of rights and liberties. We are not particularly concerned with individual support for, say, privacy rights or to whom privacy rights ought to extend (i.e., tolerance of rights expression). Rather, we focus on determining if individuals have firm preferences about rights and liberties, their basic perceptions of who can violate rights, and perceptions of threats to these constitutional guarantees, as well as partisan differences in these preferences and attitudes.Footnote 6

Partisan Differences in Rights Perceptions

A great deal of existing work has touched on partisan differences in rights and liberties attitudes, as well as elite-driven efforts that may generate or exacerbate asymmetries (more on this below). For instance, Nelson et al. (1997) find that more conservative individuals are less tolerant of free speech and rallies for the Ku Klux Klan. The main focus of their analysis, though, is on how media framing influences such attitudes. Gibson (2013) finds that partisanship predicts pro-civil liberties attitudes, but the focus is on measuring political tolerance. Further, Strother and Bennett (2021) find that racial group attitudes—often linked to political predispositions (see Enders, 2021)—underlie support for constitutional protections (also see Marcus et al., 1995). Chong (1993) highlights broad ambivalence, though does not focus on any partisan differences. While previous scholarship offers hints as to how partisanship relates to civil liberties attitudes, little research focuses directly on this question at the mass level. Addressing this lacuna is important, as there are normative concerns distinct from those regarding tolerance. For instance, political leaders may capitalize on the different conceptions of rights (that they, themselves, may generate) to achieve some goal. Indeed, some suggest conceptualizing certain policy goals as a matter of rights can help garner public support for a policy that would be unpopular if framed otherwise (Djupe et al., 2014; Lewis, 2017).

We focus on two specific rights-related concepts for which we expect to observe partisan differences. First, we consider from whom individuals perceive rights to be protective. Say one makes a statement critical of a certain racial or ethnic group. Civil liberties protect one from government reprisal for such speech (e.g., being arrested or fined), but one very well may be terminated by their employer for such speech. This would not constitute a violation of one’s rights, though popular discourse and perception indicates there is great confusion as to whether it would (e.g., Haller, 2018). We are interested in whether individuals perceive their rights to have been violated and whether they claim non-governmental entities have violated their rights. Second, we consider whether rights are perceived as protective, or whether their level of protectiveness is under threat.

We hypothesize that partisan differences in each of these perceptions will exist. In particular, we expect Republicans to be more prone to state their rights are violated across the board, and are more prone to claim their rights are violated by non-governmental entities. We also expect Republicans to be more likely to state rights are under threat. We suspect there are two general reasons for such partisan asymmetries: political polarization and asymmetries in “rights talk”. We consider each possibility in turn.

The contemporary political era in the United States is marked by wide and growing divisions across political lines (Ahler & Sood, 2018; Iyengar et al., 2012). Democrats and Republicans can scarcely agree on the major contours of salient problems, even if they perceive more polarization than exists (Ahler, 2014; Enders & Armaly, 2019). Extant scholarship on polarization gives us reason to expect partisan differences in rights perception. Indeed, all manner of stimuli—including the non-political (Iyengar & Westwood, 2015)—are polarized along party lines. Yet, polarization is unlikely to cause large rifts in rights understanding, alone. Just as polarization is transmitted in a top-down fashion from elites to the masses (Druckman et al., 2013), there is reason to believe that the understanding of rights operates similarly.

Many scholars describe a long, concerted effort in right-leaning legal and political circles to transform the understanding of rights (see, among others, Batchis, 2016; Decker, 2016; Hollis-Brusky, 2011; Lewis, 2017). As Djupe et al. (2014) write, “...the power of rights is delivered through framing” (655). Indeed, leaders on the right have shifted the framing of many of their policy goals to explicitly contain messages about rights. Conservative elites have de-emphasized morality and adopted the language of rights, which was once the domain of liberals (Lewis, 2017). While a focus on rights is accessible to the public (Jelen, 2005), this has been more than just a rhetorical shift; this rights-focus also involves changes to the legal environment. Jerry Falwell once advocated for creating “a generation of Christian attorneys who could...infiltrate the legal profession...”,Footnote 7 which Hollis-Brusky and Wilson (2020) suggest has been partially successful.

This type of rights framing among conservative leaders highlights why we expect asymmetries across parties. While both liberals and conservatives, Democrats and Republicans, are using the language of rights, the content of that rights talk is different for these groups. Moreover, modern rights discourse paints rights as both straightforward and absolute (Glendon, 1991), all the more reason that the mass public—which takes political cues in a top-down fashion (e.g., Lenz, 2012)—would hold dearly to their understanding of rights and liberties even if it does not accord with the legal understanding of rights (Chong, 1993).Footnote 8

In addition to the extant literature on the asymmetric understanding of rights, our expectations are also derived, in part, by recent rhetoric and events that highlight this asymmetry. Indeed, these events conform to well-established theories of mass political attitudes operating in a top-down fashion (e.g., Zaller, 1992). Claims of rights violations were abundant during the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily by those on the political right. Iowa, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah—states that largely support Republicans—faced federal civil rights investigations due to their opposition to masks.Footnote 9 Arkansan elected officials openly protested the governor’s mask mandate.Footnote 10 Governor Ron DeSantis threatened loss of public funding for Florida schools that implemented mask mandates.Footnote 11 Some Republican officials made misleading (or outright incorrect) claims about rights violations with respect to limitations on public gatherings (e.g., Crenshaw 23 November 2020, 7:57 PM). While there are legitimate conversations to be had about the government’s authority to, say, impose large-scale lockdowns, a grocery store’s ability to require a facial covering is, legally speaking, cut-and-dried;Footnote 12 still, some sought legal intervention (for a more detailed exploration of tensions such as this, see Greene, 2021). Importantly, our expectations of partisan asymmetry are not confined to COVID-19 related issues. Many Republican leaders refer to any gun-control measure as a violation of rights,Footnote 13 even though reasonable limitations on all liberties are common. Additionally, “cancel culture,” a phrase predominantly used by Republicans when criticizing the left, represents social reprisal for unpopular speech, but often evokes free speech claims.Footnote 14 Social media companies are often decried by conservatives for violating free speech.Footnote 15 Sewing many of these issues together, the Republican National Committee adopted a resolution in response to “the coronavirus pandemic and the cancel culture movement” in which they argued “threats to the First Amendment are escalating.”Footnote 16 While traditionally left-leaning sources are not entirely free from blame in sowing confusion about rights—for instance, the New York Times has conflated colloquial with constitutional rightsFootnote 17—Republicans seem more prone to argue that constitutional rights are being infringed upon, oftentimes when constitutional rights are not actually in question.

The public’s understanding of politics is often a product of elite-driven, top-down considerations (Lenz, 2012; Zaller, 1992), and attitudes regarding rights and liberties are partially derived from the frames one considers (Chong, 1993; Nelson et al., 1997). There is robust evidence that Republican leaders occasionally sow confusion on matters of constitutional violations. If Republican elites frequently employ frames of constitutional violations (which, as we demonstrate above, they do), these are the frames the Republican masses are likely to consider. It is for these reasons that we argue there will be asymmetries in the degree to which rights are perceived to be violated and threatened, and that Republicans will be more prone to exhibit these perceptions.

Data

To test our expectations about the partisan contours of rights and liberties preferences, we utilized Lucid to field an original survey on 1500 respondents in March 2022. The opt-in, quota-based sample is generally reflective of the U.S. adult population based on age, race, education, and sex. To additionally minimize disparities between the sociodemographic composition of the sample and U.S. adult population, we constructed raking weights using the weights and anesrake R packages. All analyses presented below utilize these weights. We compare our sample—both weighted and unweighted—to the recent U.S. census in the Supplemental Appendix.

As Coppock and McClellan (2019) note, samples using Lucid recover political attitudes of the U.S. population well, but there have been recent data quality concerns regarding Lucid (Peyton et al., 2020). Following the best practices promoted by Berinsky et al. (2014), we took additional steps beyond those employed by Lucid (e.g., reCAPTCHA to screen inattentive respondents) to ensure the quality of our data. We required respondents to pass two standalone attention checks and two presented with other survey items in matrices. Individuals were removed for failing any of the four attention checks. Additionally, we removed respondents who sped through the survey (i.e., those in the bottom fifth percentile in terms of duration, or those who took under 6 min on a survey designed to take 15 min). After removing these respondents, our final sample size is 1414.Footnote 18

Finally, we compare various attitudes among our sample to those captured on the 2020 American National Election Study—a high-quality, probability sample survey—in an effort to ensure comparability to probability samples beyond simple sociodemographic distributions. This analysis appears in the Supplemental Appendix. Across eight comparisons of feelings about political candidates, parties, and institutions, perceptions of corruption, and trust in government, we observe only minor statistically significant differences in two cases. Although we recommend caution in over-interpreting results born of non-probability samples such as ours, the quality control mechanisms and weighting scheme we utilize appear to produce a fairly representative sample.

Are Rights Attitudes Meaningful?

In this first empirical section, we ask whether individuals structure their thinking about rights and liberties in a coherent fashion and whether Democrats possess different rights preference structures than Republicans. In other words, are views of rights driven by systematic preferences? Again, it is critical to determine whether these attitudes are meaningful in order to conclude that the perceptions we examine below—such as perceived violations of rights—are not merely error-ridden (non-)attitudes. To find out, we employ the method of triads and seek evidence of transitive assessments of the importance of various rights. We ask respondents to consider three rights at a time (which comprises a triad) and indicate which they perceive to be the most important and the least important. Consider 3 objects, a, b, and c. If one believes object a is more important than object b, and that object b is more important than object c, object a should be viewed as more important than object c. This would be an example of a transitive ordering of the objects. If, however, an individual preferred a to b and b to c, but preferred c to a, their preferences are not transitive, and, therefore, not particularly crystallized or meaningful (Jacoby, 2006).

Before completing 10 triads of rights, wherein each right is pitted against each other right 3 times (for a total of 30 pairwise comparisons), respondents were provided with basic instructions: “We’d like to ask you about some rights that are important for our society…In all, we will ask you about five different rights”. Specifically, we ask about the following rights: privacy, free speech, religious freedom, bear arms, and free press. Because individuals do not have the same ex ante understand of rights (Chong, 1993), and because framing can alter the considerations one makes vis-`a-vis rights (Nelson et al., 1997), we carefully define each of the five rights for respondents so we can be more assured individuals are thinking about them similarly. For instance, the instructions define the right to free speech as “Freedom to articulate opinions and ideas without fear of legal retaliation”. The other four definitions appear in the Supplemental Appendix. The instructions to respondents continue:

All five of these rights are important, but sometimes we have to choose between what is more important and what is less important. And, the specific choices we make sometimes depend upon the comparisons we have to make.

On the next few screens, we will show you these ideas in sets of three. For each set, please indicate the right that you think is most important of the three, which right that you think is least important of the three, and which is in between.

In some cases, you might think all three of the rights are very important, but please try to indicate the ones you think are most and least important if you had to choose between them.

Approximately half, 734, of our respondents were randomly selected to participate in this task.Footnote 19 The primary question of interest regards the level of transitivity (or lack thereof) among respondents. Approximately 83% of respondents displayed perfectly transitive preferences across all 10 triads; 80% of Democrats and 87% of Republicans were perfectly transitive, a slight asymmetry that may be reflective of partisan differences in elite communication about rights (e.g., Batchis, 2016; Decker, 2016; Hollis-Brusky, 2011; Lewis, 2017). 83% average transitivity is quite high. For context, first compare this to the level of transitivity for core political values, about 90% (Jacoby, 2006). In other words, only 3–7% fewer respondents in our sample have less structured attitudes about rights and liberties than about general views of “good” and “bad” in the world, which represent the “fundamental building blocks of human behavior” (Jacoby, 2006). Next, consider that respondents rated 30 pairwise choices; transitivity in this context is certainly a function of meaningful, deep-seated preferences. That is, the probability of observing transitive preferences across 10 triads by chance alone is minuscule. Finally, rank orders that are implicitly (and, often, incorrectly) assumed to be the product of transitive preferences are typically riddled with error in the form of weak preferences, intransitive or inconsistent preferences, or measurement error—the opposite of what we find with rights preferences. All of this is to say that transitive preferences indicate that individuals do tend to possess meaningful, fixed preferences when it comes to rights, and 83% transitivity is quite high.

As the rate of transitive preferences is high, we utilize the pairwise choices to construct rank orders of rights ranking from 1 (most important) to 5 (least important). Average rankings, for the entire sample (not just the subset that completed the triad task) and by partisanship, appear in Table 1. The first column lists the rights in descending order of importance for the full sample (n = 1390): speech, privacy, religious practice, arms, and press.

Democrats (n = 632) and Republicans (n = 476) appear to agree about the right to free speech, ranking it the most important. The upper confidence interval for free speech does not overlap with the estimate for privacy among Democrats (second most important right for Democrats) or the estimate for the right to bear arms among Republicans (second most important right for Republicans). The right to privacy is also fairly bipartisan, ranking second for Democrats and third for Republicans.

Democrats view religion, press, and arms the third, fourth, and fifth most important, respectively. The average rankings for all five rights are statistically distinguishable among Democrats (i.e., no significantly overlapping confidence intervals). Among Republicans, arms is second and religion and press fourth and fifth. For Republicans, there is some uncertainty regarding privacy and free exercise of religion, the positions of which are not statistically distinguishable. Even if the order of these rights were swapped, three of five rights would be in a different ordering for Democrats and Republicans and the ordering would look more different in this situation (i.e., privacy would be fourth for Republicans and second for Democrats, whereas they are currently ranked third and second, respectively). Thus, even if we rearranged the orderings within party given the known level of uncertainty, the rankings would be different across parties.

The greatest discrepancy is owed to the right to bear arms, which is ranked second most important for Republicans and least important for Democrats. For each of these rankings, save the right to free exercise of religion, the mean response for Democrats is different from the mean response for Republicans to a statistically significant degree (at the p < 0.05 level).

Altogether, Americans—regardless of party—do appear to possess fairly crystallized preferences about which constitutional rights are most important to them. On the one hand, this may be unanticipated given Americans’ famously low levels of political knowledge and ideological constraint; indeed, a 2021 Annenberg Civics Knowledge Survey found that only 56% of Americans could identify the three branches of government.Footnote 20 On the other, perhaps this should not come as a surprise, as Americans exhibit similarly crystallized preferences about other political objects, such as values. Regardless, attitudes about rights are not only transitive, but systematically differ across party lines, suggesting a fault line in American politics that has been heretofore overlooked by contemporary investigations into polarization, the culture war, and party cleavages.

Who Violates Rights?

Having established that attitudes about rights and liberties are meaningful in some way, rather than completely random error-afflicted expressions, we next consider which groups and entities Democrats and Republicans perceived to be most likely to violate those rights and liberties. Specifically, we told respondents “We would like to get a sense of which institutions you feel have violated your constitutional rights in the past. When we say constitutional rights, we mean those in the US Constitution (as opposed to your state’s constitution). Please tell us whether each of the following has violated your rights, has not violated your rights, or you don’t know.” We ask about 12 entities, 8 of which are nongovernmental and 4 of which are governmental. Figure 1 plots the proportion of Democrats and Republicans who claim that a given entity has violated their constitutional rights.Footnote 21 We are interested in two comparisons: Whether there are partisan differences in the overall perception of rights violation, and whether there are partisan differences in the perception that non-governmental entities have violated rights. Again, we expect Republican identifiers to be higher in each perception.

Democrats were most likely to say that the local police violated their rights and least likely to say as much about banks. Republicans were most likely to say that the federal government violated their rights and least likely to say as much about medical professionals (with banks coming in a close second). In both instances, individuals from both parties agreed that entities actually capable of violating their constitutional rights—local police and the federal government—did so; this may be suggestive of some understanding of the basic mechanics of rights, namely from whom or what they protect Americans.

They also showcase the impact of partisan motivations. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests, Democratic opinion leaders have been much more likely to scrutinize police than Republican opinion leaders, who are more strident in their support for law enforcement. We also observe stark partisan differences when it comes to perceived violations by state governments, social media, and media outlets (the largest discrepancy). These patterns comport with the results of other polling on trust in media and journalism showing partisan asymmetries.Footnote 22 Perhaps more importantly, social media companies and other media outlets are not capable of violating constitutional rights.

Although we find that a higher proportion of Republicans perceived violations of rights, on average, compared to Democrats, we must also emphasize that a non-trivial proportion of both Democrats and Republicans appear to be uncertain about from whom or what constitutional rights protect them. Even on the low end, 20% of Americans believe that banks have violated their rights; more than 40% of Republicans believe that social media companies and other media outlets have done so. There are at least a few ways to interpret these patterns. The most obvious interpretation is that Americans are not particularly knowledgeable about what rights entail. Faced by a knowledge gap, partisan motivations, presumably in addition to a host of idiosyncratic individual experiences with the entities we asked about, are used to guide thinking about rights violations. While it is possible that more Democrats have, indeed, had their rights violated by police, and more Republican identifiers by the federal and state government, the frequency with which respondents report violations by non-governmental entities indicates these perceptions are not derived from genuine, experienced rights violations (at least not those that would be recognized as violations under the law). On the other hand, it could be that respondents generally prefer broad deference for individual liberties regardless of whether a given entity is public or private and, therefore, legally capable of violating constitutional rights. In such a case, our instrument may be soliciting an expressive response about desires, rather than knowledge alone. This seems like a reasonable possibility given the impact of elite rights talk on perceptions of rights (e.g., Djupe et al., 2014; Glendon, 1991). Ultimately, it seems to us that the patterns we observe are likely to be a joint production of weak civics knowledge and political/cultural differences fostered by (partisan differences in) elite rhetoric.

Next, we move beyond mere proportions to examine the robustness of the relationship between partisanship (in particular, Republican identification) and perceptions of rights violation in the face of control variables. We construct two dependent variables from the information in Fig. 1: the proportion of the non-governmental entities one affirms has violated their rights, and the proportion of governmental entities one affirms has violated their rights. We separately regress these variables onto partisanship, ideology, political knowledge, interest in politics, and a host of demographic characteristics.Footnote 23 Two attitudinal variables—support for the rule of law and pro-civil liberties attitudes—are also included, as they may impact both the degree to which one believes their rights have been violated, as well as differentially impact whether one thinks their rights are violated by non-governmental entities (see Gibson, 2013).Footnote 24 The results of these regressions appear in Table 2.

Consistent with our hypotheses about partisan asymmetry in perceptions of constitutional violations, Republican identification (i.e., positive coefficients on the partisanship variable) relate to rights violation perceptions, even when accounting for attitudes like support for the rule of law and interest in politics (which are also statistically significant). Partisanship is statistically significant in both models; indeed, per the standardized regression coefficients (i.e., in the β columns), partisanship is one of the strongest predictors of violation perception. Thus, the results presented in Fig. 1 do not appear to be a function of the idiosyncrasies of the entities we asked respondents about or the spurious product of other attitudinal asymmetries in knowledge about rights or support for the rule of law. Rather, these perceptions—both regarding governmental and non-governmental entities—appear to be stable and related, in part, to partisanship.

One interpretation of the results presented thus far is that the high levels of transitivity reported above are moot in light of partisan-guided (mis)conceptions of constitutional liberties. We argue the exact opposite. Rights and liberties are clearly important to Americans, and they have remarkably consistent preferences about which are more important than others. Yet, Americans seem to have a weak understanding of what those rights entail, despite the obvious importance of the subject.

Which Rights are Under Threat?

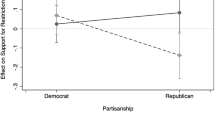

Finally, we investigate the possibility of partisan asymmetries in perceptions about which rights are under threat. Specifically, we told respondents “We’d like to know if you think these rights are more or less threatened now than they were in the recent past.” Using a three-point scale—less threatened (1), neither more nor less threatened (2), more threatened (3)—respondents assessed the perceived threat to the nine rights listed in Fig. 2.

Across the board, Americans perceive constitutional rights to be more threatened (between 2 and 3) than not (between 1 and 2). We observe statistically significant differences between Democrats and Republicans in all cases except free press (p = 0.81) and self-incrimination (p = 0.09). In only one case—abortion rights—do Democrats perceive a greater threat to rights than do Republicans. Even though our data were collected well before the now infamous leak of the Samuel Alito-authored majority opinion arguing that the Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey decisions should be overturned, a tangible threat to this right would be revealed shortly after the survey was fielded (one might also say as much about the right to privacy, from which abortion rights are derived).

Hence, we do not argue that concerns about threats to rights are inherently inappropriate or misguided. Rather, we are interested in the extent to which partisans perceive threats and for which rights. Democrats are most concerned about abortion, Republicans about the right to bear arms. Republicans are also concerned about free speech and religious freedom—both central to the contemporary Republican lexicon. In this sense, partisan motivations color perceptions regardless of the right under consideration. Yet, Republicans appear to be more concerned about more rights—a pattern that we argue stems from the elite-driven “rights talk” discussed above and could result in support for policy actions designed to reduce perceived threats (even those actions that might end up harming rights protections through another lens).

Just as we did with questions about who violates rights, we examine whether the relationship between partisanship and perceptions of which rights are threatened are robust to controls. We generate a variable that measures the degree to which on believes rights are threatened by averaging responses across all 9 rights; this forms a reliable scale (α = 0.790; M = 0.680, SD = 0.207 on 0–1 scale) which we regress onto the same independent variables in Table 2 above. Model estimates appear in Table 3.

Partisanship (or, more specifically, Republican identification) relates to the perception that rights are generally threatened even when accounting for other attitudes, identifications, and knowledge about politics. Indeed, partisanship is second only to pro-civil liberties attitudes in the strength of its relationship with threat perception (per the standardized regression coefficients in the β column). Thus, we find further supporting evidence that beliefs about the basic mechanics of civil rights and liberties are colored by partisanship.

Conclusion

In this paper, we set out to assess the partisan contours of rights and liberties attitudes. We find that Americans appear to possess highly crystallized attitudes about the rights and civil liberties most important to them, potentially surprising in light of longstanding findings regarding their weak democratic capacities (e.g., comparatively low levels of political knowledge, participation). Unfortunately, our remaining findings are less optimistic. Preferences regarding many rights are colored by partisan motivations, as are many perceptions of who and what violates rights and how threatened rights are. Democrats perceive violations by the local police, while Republicans focus on the federal and state governments and media companies. Democrats perceive threats to abortion rights (prior to the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision), while Republicans are concerned about the right to bear arms, free speech, and religious freedom. Moreover, Republicans—presumably in reaction to top-down Republican rhetoric, at least in part—exhibit greater concern about threats to constitutional rights, and are more likely than Democrats to pin rights violations on non-governmental entities incapable of violating constitutional rights.

Altogether, familiarity with the basic mechanics of constitutional rights and civil liberties appears to be lacking, and partisan motivations fill in the gaps in predictable ways. Our findings contribute yet another piece of evidence regarding the relatively weak democratic capacities of the American mass public. Uncertainty in the political realm applies not only to current events or historical minutia, but to unique features of American representative democracy that are fundamental, in many ways, to American national identity.

One primary implication of the partisan contours regarding constitutional rights is that public opinion can be more easily manipulated and molded by co-partisan elite rhetoric. As showcased above, this is not merely a hypothetical, but a reality. Elite “rights talk” not only distracts from other political issues, but chips away at the bedrock of American democracy by misinforming the public about what, exactly, a rights violation entails and framing rights as partisan issues (see Glendon, 1991). Moreover, many proposed partisan “solutions” to perceived infringements on rights, themselves, entail infringement on rights—real infringements. Florida, for instance, has combated perceived limitations on expression by “woke culture” and “cancel culture” by statutorily imposing genuine limitations on expression;Footnote 25 at a minimum, the Stop WOKE Act likely creates a chilling effect on speech,Footnote 26 a legitimate constitutional violation.

Our investigation is not without limitations. For starters, there are social, legal, and political conceptualizations of rights. We do not consider whether individuals recognize or differentiate between these conceptualizations. Consider a landlord who prohibits the display of religious symbols on his property; an individual who believes she has a general, social right to free exercise of religion may call this a violation, even if she does not perceive it as a constitutional violation (for a more detailed exploration of tensions such as this, see Greene, 2021). Indeed, many perceive rights as “nonnegotiable prerogatives that lie beyond the legitimate scope of any authority” (Djupe et al., 2014, p. 653; also see Glendon, 1991; Persily et al., 2008). Although our focus was on assessing understanding of and asymmetry in rights using a legal understanding as a baseline, we encourage future research to investigate how well individuals perceive the boundaries between state action and non-state action, as well as legal versus social understandings of rights.

Further, we were not exhaustive in our examination of all civil rights and liberties. Indeed, we explicitly focused on the rights that we believed most Americans would be at least somewhat familiar with. In this sense, our conclusions might actually be more optimistic than warranted, though we encourage future work to replicate and extend our analyses with attention to more rights. We also believe it would be useful to examine other political, psychological, and social correlates of rights and liberties perceptions—beyond partisanship—in order to better understand among whom misunderstanding persists and to gain clues about the potential consequences of misunderstanding.

Finally, all of the usual caveats apply to non-probability samples. In particular, quota-based sampling, while generating samples with some characteristics that appear to be reflective of the broader population, may not generalize in all aspects to the population. For example, it could be the case that either more or less than 83% of Americans hold transitive preferences about rights. Ultimately, only additional data collections—ideally using probability samples—can answer this question. Until we have a tighter grasp on the contours of attitudes about rights, we urge caution in interpreting more than general patterns. That said, that so many respondents exhibit perfectly transitive preferences across 10 triads suggests that respondent attention was relatively high—indeed, the probability of achieving perfect transitivity by accident is minuscule. Moreover, the high degree of correspondence we observe when comparing attitudes from our sample with those from a high-quality probability sample (see reference above and Supplementary Appendix materials) are encouraging. Still, we strongly encourage replications and extensions of the analyses presented above.

Notes

Civil liberties refer to personal freedoms protected by the Bill of Rights (and the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment). Civil rights refer to statutory legal protections (e.g., the Civil Rights Act of 1964). Colloquially, however, liberties are often referred to as rights. We use the terms interchangeably, though recognize that legal differences exist.

Generally speaking, civil liberties are protections from the government. While there are statutory considerations (e.g., various Civil Rights Acts), and entanglements between private entities and the government can make private discrimination a state action, our survey instructions clearly referred to violations of constitutional guarantees. Thus, we consider perceived violation of rights by, say, businesses to be an “incorrect” understanding of rights.

We note that there is a robust literature on the concept of “rights consciousness,” or “how prevailing legal ideas and institutions acquire social meaning and how this social meaning helps to constitute the social world” (Gabel, 1983, also see Aaronson & Barzilay, 2019; Engel, 2012; Greenhouse, 2012). For instance, Engel and Munger (2003) consider how legislation regarding civil rights impacts ordinary individuals, and how that underlies feelings about the law. This literature—which is largely confined to critical legal studies—argues that a rights consciousness understanding would focus on the role that the law, including rights and liberties, plays in everyday lives, as opposed to a formal, legalistic approach. In a sense, we follow in this tradition; we wish to understand the ways ordinary Americans feel about constitutional rights and liberties, how these rights and liberties acquire meaning, and which sociopolitical constructs (e.g., partisanship) underlie such meaning. Yet, inasmuch as individuals and political leaders make claims about what rights do and do not allow, comparison to a concrete, legal understanding of what rights confer is an important consideration. Indeed, if the method by which the prevailing legal ideas acquire social meaning is via partisanship, then this plays an important role in our understanding of the social and legal world.

There is some debate as to whether rights talk polarizes or promotes discourse (e.g., Djupe et al., 2014; Glendon, 1991). As our theory is predominantly about intra-party rights cue-taking, we remain agnostic as to the effects of inter-party rights appeals. In short, rights rhetoric need not polarize to remain asymmetric.

Our survey was designed so inattentive respondents were removed via survey logic as soon as they failed an attention check question. Thus, we were able to maintain a sample that matches the national population, as Lucid would replace removed respondents with a demographically similar one in order to meet quotas.

The other half of our respondents simply rank-ordered their rights preferences. Because we find high levels of transitivity, we can be certain that the rank-ordered rights are not merely error-ridden assessments. Rather, they are meaningful orderings of preferences regarding rights and liberties. Thus, we report rights preferences for the entire sample.

In the Supplemental Appendix, we also plot the proportion of Democrats and Republicans answering “don’t know” to each of the questions. It could be that Democrats or Republicans are more (less) certain—whether they are “correct” or not—about which entities have violated their rights. We find scant evidence for this proposition; only in the case of social media and media outlets do we observe a statistically significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) in the proportion of “don’t know” responses between parties. In both cases, Republicans report less uncertainty in the form of “don’t know” responses (6 percentage points more “don’t know” responses to social media, 8 percentage points to media outlets).

All variables are scaled to range from 0 to 1 to facilitate comparison of effect sizes

See the Supplemental Appendix for question wording.

References

Aaronson, E., & Barzilay, A. R. (2019). Rights-consciousness as an object of historical inquiry: Revisiting the constitution of aspiration. Law & Social Inquiry, 44(2), 505–511.

Ahler, D. J. (2014). Self-fulfilling misperceptions of public polarization. Journal of Politics, 76(3), 607–620.

Ahler, D. J., & Sood, G. (2018). The parties in our heads: Misperceptions about party composition and their consequences. Journal of Politics, 80(3), 964–981.

Barabas, J., Jerit, J., Pollock, W., & Rainey, C. (2014). The question (s) of political knowledge. American Political Science Review, 108(4), 840–855.

Batchis, W. (2016). The Right’s first amendment: The politics of free speech & the return of conservative libertarianism. Stanford University Press.

Berinsky, A. J., Margolis, M. F., & Sances, M. W. (2014). Separating the shirkers from the workers? Making sure respondents pay attention on self-administered surveys. American Journal of Political Science, 58(3), 739–753.

Chong, D. (1993). How people think, reason, and feel about rights and liberties. American Journal of Political Science, 37, 867–899.

Combs, M. W., & Welch, S. (1982). Blacks, whites, and attitudes toward abortion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 46(4), 510–520.

Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research and Politics, 2019, 1–15.

Crenshaw, D. (2020). Prosecuting People for Holiday Gatherings Inside Their Own Home Violates the 4th Amendment—Protection from Unreasonable Search & Seizure. Tweet.

Davis, D. W., & Silver, B. D. (2004). Civil liberties vs security: Public opinion in the context of the terrorist attacks on America. American Journal of Political Science, 48(1), 28–46.

Decker, J. (2016). The other rights revolution: Conservative lawyers and the remaking of American government. Oxford University Press.

Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. Yale University Press.

Djupe, P. A., Lewis, A. R., Jelen, T. G., & Dahan, C. D. (2014). Rights talk: The opinion dynamics of rights framing. Social Science Quarterly, 95(3), 652–668.

Druckman, J. N., Peterson, E., & Slothuus, R. (2013). How elite partisan polarization affects public opinion formation. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 57–79.

Enders, A. M. (2021). A matter of principle? On the relationship between racial resentment and ideology. Political Behavior, 43(2), 561–584.

Enders, A. M., & Armaly, M. T. (2019). The differential effects of actual and perceived polarization. Political Behavior, 41(3), 815–839.

Engel, D. M. (2012). Vertical and horizontal perspectives on rights consciousness. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 19(2), 423–455.

Engel, D. M., & Munger, F. W. (2003). Rights of inclusion: Law and identity in the life stories of Americans with disabilities. University of Chicago Press.

Erskine, H. (1970). The Polls: Freedom of speech. Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(3), 483–496.

Fowler, R. B., Olson, L. R., Hertzke, A. D., & Den Dulk, K. R. (2018). Religion and politics in America: Faith, culture, and strategic choices. Routledge.

Gabel, P. (1983). Phenomenology of rights-consciousness and the pact of the withdrawn selves. Texas Law Review, 62, 1563.

Gibson, J. L. (2013). Measuring political tolerance and general support for pro–civil liberties policies: Notes, evidence, and cautions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(S1), 45–68.

Gilens, M. (2001). Political ignorance and collective policy preferences. American Political Science Review, 95(2), 379–396.

Glendon, M. A. (1991). Rights talk: The impoverishment of political discourse. Free Press.

Greene, J. (2021). How rights went wrong: Why our obsession with rights is tearing America apart. Mariner Books.

Greenhouse, C. J. (2012). Dimensions of rights consciousness. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 19(2), 457–466.

Haller, B. (2018). Kneel and you’re fired: Freedom of speech in the workplace. Faculty Works: Business, 54, 1.

Hollis-Brusky, A. (2011). Support structures and constitutional change: Teles, Southworth, and the conservative legal movement. Law & Social Inquiry, 36(2), 516–536.

Hollis-Brusky, A., & Wilson, J. C. (2020). Separate but faithful: The Christian Right’s radical struggle to transform law & legal culture. Oxford University Press.

Iyengar, S., Sood, G., & Lelkes, Y. (2012). Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opinion Quarterly, 76(3), 405–431.

Iyengar, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2015). Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 690–707.

Jacoby, W. G. (2006). Value choices and American public opinion. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 706–723.

Jelen, T. G. (2005). Political Esperanto: Rhetorical resources and limitations of the Christian right in the United States. Sociology of Religion, 66(3), 303–321.

Lenz, G. S. (2012). Follow the leader? How voters respond to politicians’ policies and performance. University of Chicago Press.

Lewis, A. R. (2017). The rights turn in conservative Christian politics: How abortion transformed the culture wars. Cambridge University Press.

Lupton, R. N., Myers, W. M., & Thornton, J. R. (2015). Political sophistication and the dimensionality of elite and mass attitudes, 1980–2004. Journal of Politics, 77(2), 368–380.

Marcus, G. E., Theiss-Morse, E., Sullivan, J. L., & Wood, S. L. (1995). With malice toward some: How people make civil liberties judgments. Cambridge University Press.

Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (1997). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review, 91(3), 567–583.

Persily, N., Citrin, J., & Egan, P. J. (2008). Public opinion and constitutional controversy. Oxford University Press.

Peyton, K., Huber, G. A., & Coppock, A. (2020). The generalizability of online experiments conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 9, 3.

Scheufele, D. A., Nisbet, M. C., & Ostman, R. E. (2005). September 11 news coverage, public opinion, and support for civil liberties. Mass Communication & Society, 8(3), 197–218.

Strother, L., & Bennett, D. (2021). Racial group affect and support for civil liberties in the United States. Politics, Groups, and Identities. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2021.1946101

Sullivan, J. L., & Hendriks, H. (2009). Public support for civil liberties pre-and post-9/11. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 5, 375–391.

Sullivan, J. L., Marcus, G. E., Feldman, S., & Piereson, J. E. (1981). The sources of political tolerance: A multivariate analysis. American Political Science Review, 75(1), 92–106.

Zaller, J. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. Cambridge University Press.

Funding

Funding was provided by the University of Mississippi College of Liberal Arts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

This research uses human participants, who provided informed consent and were debriefed at the end of the survey.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Replication data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0WI68H via the Political Behavior Harvard Dataverse.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Armaly, M.T., Enders, A.M. The Partisan Contours of Attitudes About Rights and Liberties. Polit Behav (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09860-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-023-09860-3