Abstract

The aim of this paper is to argue that lying differs from mere misleading in a way that can be morally relevant: liars commit themselves to something they believe to be false, while misleaders avoid such commitment, and this difference can make a moral difference. Even holding all else fixed, a lie can therefore be morally worse than a corresponding misleading utterance. But, we argue, there are also cases in which the difference in commitment makes lying morally better than misleading, as well as cases in which the difference is not morally relevant. This view conflicts with the two main positions philosophers have defended in the ethics of lying and misleading, which entail either that lying is in virtue of its nature worse than misleading or that there is no morally relevant difference between lying and misleading.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

When faced with a choice between lying or attempting to mislead, which means of deception should we opt for? Theorists in the philosophical debate on this matter tend to argue for a general answer to this question. On the one hand, there is the traditional and still popular philosophical view that lying is in virtue of its nature worse than misleading (see e.g. Chisholm and Feehan 1977; Adler 1997, 2018; Strudler 2010; Webber 2013; Berstler 2019; Pepp 2020). According to this view, we should choose to mislead rather than to lie (except in certain special cases). On the other hand, Bernard Williams (2002) and Jennifer Saul (2012a, b) have recently argued that there is no such morally relevant difference between lying and misleading. On this view, the choice between lying and misleading does not matter from a moral perspective (again, except in certain special cases).Footnote 1

The aim of this paper is to argue for a non-general answer to the initial question. We will try to make plausible that there is indeed a morally relevant difference in the nature of lying and misleading, but that this difference plays out in a non-unified way: as a result, there are some cases in which lying is worse than misleading, other cases in which lying is better than misleading and yet other cases in which there is no moral difference between the two options.

The main challenge for views that do not take lying and misleading to be morally on a par is to ground this moral difference in a non-moral difference between the two means of deception. Saul (2012a, b) forcefully argues that there is no such non-moral difference: both lies and misleading utterances aim at deceiving the addressees, and which means of deception one chooses does not matter from a moral perspective. Against Saul, we will argue that the natures of lying and misleading do differ in a way that accounts for a difference in their moral evaluation: liars commit themselves to something they believe to be false, while misleaders avoid such commitment. This difference makes it possible that lying is worse than misleading in some cases, so Saul is too quick to dismiss any morally relevant difference between lying and misleading. But the traditional philosophical position of a general moral preference for misleading is also mistaken. For one thing, the difference in commitment can sometimes be part of the explanation why lying is better than misleading; and for another thing, the difference is not always relevant to the moral evaluation, and if that is the case, lying and misleading are morally on a par. This is because, as we will try to show, commitment allows different moral factors to bear on the overall moral evaluation of the action in different cases, and it does not matter in every case.

2 The choice between lying and misleading

To begin with, let us introduce a few cases in which communicative agents are faced with a choice between a lie and a corresponding misleading utterance. This will help to clarify the distinction between lying and misleading, the relevant choices between lying and misleading, and the intuitions commonly expressed about such choices.Footnote 2

First of all, there are cases in which lying seems to be worse than a corresponding attempt to mislead. For example, consider the well-known case of the dying woman asking about her son:

Case 1: The Dying Woman

A dying woman asks a doctor whether her son is well. The doctor saw the son yesterday, when he was fine, but knows that he was killed shortly afterwards. The doctor utters:

Version A:

- (1):

He’s fine.

Version B:

- (2):

I saw him yesterday and he was fine.Footnote 3

With either utterance, the doctor intends to communicate that the dying woman’s son is well. However, while the doctor’s utterance of (1) is a clear case of a lie, her utterance of (2) is a case of misleading without being a lie—after all, the doctor did see the son yesterday, when he was fine. Moreover, most people would say that it is morally worse for the doctor to lie about the son’s health by uttering (1) than to attempt to mislead the dying woman (about the same matter) by uttering (2).Footnote 4 This intuition is acknowledged even by those who do not take (2) to be better than (1), e.g. Saul (2012a: 87).

The choice between uttering (1) or (2) can be considered from different perspectives. On the one hand, we can consider the perspective of the communicative agent facing the question what to do in a given situation and weighing the reasons for and against a possible course of action. This may be called the deliberative perspective. On the other hand, we can evaluate the agent’s decision as onlookers, from the outside. This is the evaluative perspective. The two perspectives may lead to different outcomes: what is better from the deliberative perspective need not be better from the evaluative perspective, and vice versa. In the current situation, however, misleading is preferable to lying from both perspectives.

While the difference between the deliberative and the evaluative perspective is seldom made explicit, it is clear that theorists working on the matter are interested in the deliberative perspective. For example, here is a representative passage in which Saul frames her main thesis from the deliberative perspective:

Suppose, then, that you are faced with a need to deceive. […] Should you, then, carefully construct a truthful but misleading utterance rather than simply lying? It seems to me that you should not. You should simply go ahead and lie. Or if you do choose to merely mislead, you shouldn’t do so in the comforting belief that you are thereby doing something better. (Saul 2012b: 8)Footnote 5

In keeping with this practice, it is the question whether there is a morally relevant difference between lying and misleading from the perspective of the deliberating agent that we are concerned with in this paper.

The question might also be put thus: Are there any moral reasons grounded in the nature of lying and misleading that favour the one over the other? This way of putting the question allows to bracket off both non-moral reasons (such as the fact that it is easier to simply affirm the opposite of the truth than to come up with an elaborate misleading story) and contingent moral reasons (such as a promise never to lie, or a promise never to mislead). What we are interested in are cases in which a moral difference between lying and misleading appears to be grounded in the fact that the one is a lie and the other an attempt to mislead.

Now let us turn to a second, less dramatic example in which lying seems worse than misleading:

Case 2: Paintings at an Exhibition

Amy is attending a vernissage at a small gallery. She gets talking to Bill and finds out that he is the painter of the works on display. Bill asks Amy: ‘Do you like the paintings?’ While Amy thinks that the paintings show a very good mastery of composition and excellent brushwork, she does not like them overall. However, Amy is unsure whether Bill wants an honest answer, so instead of:

Version A:

- (3):

Yes, I like them.

she says:

Version B:

- (4):

The composition is great and the brushwork is excellent.

Through either utterance, Amy intends to communicate that she likes the paintings, but only her utterance of (3) is a lie, while (4) is an attempt to mislead. In this case, too, it seems worse for Amy to lie to Bill than to attempt to mislead him.

The foregoing cases fit well with views on which lying is generally worse than misleading. But there are also cases that lead to intuitions that point in a different direction. In the following example, lying and attempting to mislead appear to be morally on a par. The example is due to Saul (2012a: 73), but we have modified it slightly to remove its most controversial featuresFootnote 6:

Case 3: The Peanut Attack

George is cooking dinner for Frieda. He knows that Frieda has a moderate peanut allergy and that peanuts will give her a stomach ache. He wants Frieda to have a stomach ache and has asked his flatmate Hans to sneak some peanuts into the meal while George and Frieda are on the balcony. Frieda, being rightly cautious, asks whether George has put any peanuts in the meal. George utters the true but misleading (6) rather than the false (5):

Version A:

- (5):

There are no peanuts in the meal.

Version B:

- (6):

I didn’t put any peanuts in.

Once again, both utterances are meant to communicate the same message, namely that there are no peanuts in the meal. In contrast to the previous cases, however, it seems to make no moral difference whether George lies by uttering (5) or attempts to mislead by uttering (6). Both utterances appear to be equally bad.

This example also differs from the previous examples with respect to the deontic status of the utterances: while utterances (1) to (4) are all permissible, utterances (5) and (6) are both impermissible. Still, the current example also exemplifies a property all of the examples in this paper have in common: the choice between lying and misleading does not seem to lead to a different deontic status. Though there are cases in which lying is intuitively worse than misleading (and also, as we will shortly see, cases in which lying is intuitively better than misleading), it is dubitable whether there are cases in which intuitions tell us that lying is impermissible while misleading is permissible (or vice versa).

As a second case in which lying and misleading do not differ morally, consider the following example by Baumann (2015: 25):

Case 4: The Unfaithful Spouse

Paul suspects that his wife Paula is having an affair with Peter. When Paula gets home in the evening, Paul asks whether she met Peter. Paula did meet Peter, though only briefly, as she had to put in some extra hours at work. Paula utters the true but misleading (8) rather than the false (7):

Version A:

- (7):

No, I didn’t meet him.

Version B:

- (8):

I had to put in some extra hours at work.

In this case, too, both utterances communicate the same message, and both utterances are impermissible. Moreover, Paula’s deception is made no better by her choice to mislead rather than to lie.

Finally, we want to turn to cases in which lying is intuitively better than attempting to mislead. A first such example (Case 5: Kant’s Murderer) is offered by Kant’s infamous murderer at the door. When the murderer asks about the whereabouts of his innocent victims, it appears as obviously permissible to attempt to deceive him. But it is also clearly better to lie rather than to attempt to mislead (pace Kant VIII: 427). After all, the latter choice might arouse suspicion (‘Why didn’t she answer my question?’) and lead to the death of the victims.

For a second example in which lying appears to be better than misleading, consider the following case:

Case 6: The Willingly Deceived Cook

John is an ambitious and passionate amateur chef, but unfortunately not blessed with too much talent. His wife, Joanne, has repeatedly had the experience that John got quite upset when she showed too little enthusiasm about his culinary achievements, or even criticized some meal he prepared. From this she has drawn the conclusion that John prefers an insincere compliment to an honest appraisal of his products. When John once again puts too much salt in the soup and asks whether she enjoyed the meal, Joanne could either utter the false (9) or the true but misleading (10):

Version A:

- (9):

It was the best fish soup I’ve ever tasted. It was delicious!

Version B:

- (10):

My mother used to cook that soup on Christmas Eve. I loved it.

Given that Joanne knows that John does not want to know the truth about his soup but prefers to be falsely complimented, it seems better for her to go for the safer option and to lie rather than to mislead. As in the previous case, a misleading answer that dodges John’s question could arouse suspicion and uncover her attempted deception.

In the current case, the addressee has made clear by his behaviour that he prefers to be deceived. This is in fact quite common in everyday life: We frequently find ourselves in situations in which it is clear from the context that our addressee does not want a sincere answer, even if this is not explicitly stated (‘Do you like my new hair colour?’, ‘What do you think of my new bike?’). But there are also situations where a person has made an explicit statement that she does not want to know the truth about a certain matter, e.g. about her husband’s affairs. And there are situations where the truth would be dangerous for the addressee himself, as in cases of temporary insanity (cf. Plato: Rep. 331a). In all these cases, it seems safer and better to lie than to mislead (though see Adler 2018: 307–308 for a contrary opinion).

What should we make of these examples and the intuitions they generate? On the one hand, the intuitions conflict with Saul’s view that there is no moral difference between lying and misleading (except in certain special cases). Firstly, the examples featuring an intuitive moral difference between lying and misleading (in either direction) do not seem to belong to the special cases for which Saul does see a moral difference: such cases must be set in legal contexts or other contexts that are similar to legal contexts (see Saul 2012a: 95–99), but the relevant examples do not feature a legal or legal-like context. Secondly, if the contexts of the examples are taken to be relevantly similar to legal contexts, then there are many cases with legal-like contexts, which means that the cases in which there is a moral difference between lying and misleading are not nearly as exceptional as Saul claims.

On the other hand, the intuitions also conflict with the standard view that lying is generally worse than misleading (except in special cases). Adherents of that view do not often make clear in which special cases lying is not worse than misleading.Footnote 7 But there are plenty of cases (similar to cases 3–6) in which lying is intuitively at least as good as misleading, and so there would have to be many exceptions to a view on which lies are generally worse than misleading—so many that it would be incorrect to speak of a general (or defeasible) moral advantage of misleading over lying.

Taken together, the intuitions about these examples support a view on which the relationship between lying and misleading is variable: a view which sees lying as worse than misleading in some cases, better in others, and which sees no difference in yet other cases. Such a non-general view is the only view that avoids ascribing widespread error in our moral judgements. It is the view we are going to defend in what follows.

3 Lying, misleading and commitment

Intuitions seem to favour a view on which lying and misleading are not always morally on a par. As mentioned above, any such theory faces the challenge of pointing to a difference in the natures of lying and misleading that could explain how a moral difference can obtain. Indeed, Saul (2012a) forcefully argues that lying and misleading do not differ in a way that could ground a moral difference. In this section, we will respond to Saul’s line of argument by pointing to a difference between lying and misleading that has been largely neglected: liars commit themselves to something they believe to be false, while misleaders avoid such commitment. In the following section, we will then show how this difference in commitment is sometimes, but not always, significant for the moral evaluation of the respective acts.

Saul’s line of argument can be summed up as follows:

In lying as in attempting to mislead, a speaker tries to convey something she believes to be false. The only difference between such communicative acts consists in whether the speaker says something she believes to be false or whether she tries to convey a false belief by some other means. But this difference cannot ground a morally relevant difference between lying and misleading.Footnote 8

So, in Saul’s view, the difference between lying and misleading is merely a difference between different means to a common goal (such as shooting someone with one brand of gun rather than another, see Saul 2012b: 7). Along these lines, Saul dismisses several proposals for morally relevant differences between lying and misleading, arguing either that lying and misleading do not differ in the way the proposals claim or that the proposed difference is not morally relevant. For example, she considers Chisholm and Feehan’s (1977: 153) point that lying involves a breach of faith that misleading avoids and objects that lying and misleading do not in fact differ in this way (cf. Saul 2012a: 75–77). And against Adler’s (1997: 444) view that in misleading (but not in lying) the addressee is partly responsible for the deception, Saul objects that such a difference could not be morally relevant (cf. Saul 2012a: 80–82).

Our aim in this section is not to defend these existing approaches, but rather to highlight a difference between lying and misleading that Saul overlooks. While Saul holds that lying and misleading differ only in terms of what is said, that is not quite right. Lying and misleading also differ with respect to the commitment undertaken by the speakers: through lying, agents commit themselves to a proposition they believe to be false; by contrast, misleaders intend to communicate a proposition they believe to be false, but do not commit themselves to this proposition.Footnote 9 What is the nature of this commitment? And which reasons are there to think that lying and misleading indeed differ in terms of commitment?

We think that the commitment in lying should be construed as the commitment in assertion. That assertion is characterised by taking on a commitment to a proposition has been proposed e.g. by Peirce (1934), Searle (1979), Brandom (1983), Rescorla (2009), MacFarlane (2011) and Kölbel (2011). A recurring idea in this literature is that through committing oneself to p one assumes a responsibility to defend p if challenged—one takes on a justificatory responsibility (Brandom 1983: 641). That seems right. But it is important to note that assertion is not the only speech-act that leads to a justificatory responsibility: the same holds for weaker constatives (i.e. speech-acts that aim at truth), such as conjectures and speculations. However, the committal speech-act of assertion differs from weaker, non-committal constatives with respect to the strength of the required defence. While assertions require a strong defence of the propositions put forward, conjectures, speculations and guesses only require a weak defence.Footnote 10

To flesh out this picture, it will help to consider some constatives and ways in which they can be legitimately challenged. Let us assume that (11) is uttered as an assertion, while the hedged (12) is uttered as a conjecture:

- (11):

Switzerland has 26 cantons.

- (12):

Switzerland has 26 cantons, I think.

Utterances of (11) or (12) are constative speech-acts with the same content: the respective speakers of (11) and (12) both put forward the proposition that Switzerland has 26 cantons. But the speech-acts differ with respect to their force: With (11), the proposition that Switzerland has 26 cantons is put forward in a committal way; the speaker takes on a justificatory responsibility to provide a strong defence if challenged. By contrast, (12) is used to put forward the same proposition in a non-committal way; the speaker does take on a justificatory responsibility, but the defence need not be as strong.Footnote 11

In line with this difference in force, there is a difference in how the speech-acts can be legitimately challenged.Footnote 12 Having uttered (11), the speaker can be legitimately challenged in a strong way. For example, challenges of the following kind would be legitimate:

- (13):

How do you know?

- (14):

How can you be sure?

Such challenges would be too strong in response to (12), and could consistently be dismissed (‘I never claimed that…’). But (12) can be legitimately challenged in a weaker way:

- (15):

What makes you think that?

- (16):

Why are you inclined to think that?

Note that what matters here is whether a challenge is legitimate in view of the speech-act that is being challenged; we are thus concerned with legitimacy ‘so far as the logic of the discourse goes’, as Unger (1975: 263) puts it. Other factors can affect the overall legitimacy of a challenge. For example, a challenge could be illegitimate because it contains a slur. As far as possible, such other factors must be bracketed here.

These patterns of constatives and legitimate challenges support the view sketched above, according to which both strong and weaker constatives lead to a justificatory responsibility, but differ in terms of the required strength of the defence. They also provide some insight into the nature of the respective justificatory responsibilities. In general, speakers can defend themselves by providing propositions that support the propositions originally put forward (cf. Rescorla 2009: 104 and Kölbel 2011: 67). The stronger the original speech-act, the stronger the support that has to be provided. Following an assertion, a speaker can, for example, defend herself by making evident that she has knowledge of the proposition she asserted. Following a conjecture, it suffices to point out that she took the proposition put forward to be possible or likely. The commitment in assertion, then, is the justificatory responsibility to deliver a strong defence.

Now, we think that lying differs from misleading in the same way as asserting differs from weaker constatives. In lying, speakers assert something they believe to be false: they take on a responsibility to provide a strong defence of the proposition put forward. In misleading, on the other hand, speakers avoid commitment to something they believe to be false. In the examples considered above, they do so through using conversational implicatures: instead of uttering a sentence that encodes the proposition they believe to be false, they utter a different sentence whose encoded proposition they (usually) believe to be true. Of course, with respect to the proposition encoded by the sentence uttered misleaders commonly take on a responsibility to provide a strong defence: when the doctor in our first example utters (2) (‘I saw him yesterday and he was fine’), she takes on a commitment to having seen the son yesterday and to him being fine then.Footnote 13 But, and this is the crucial point, with respect to the proposition they believe to be false and intend to mislead about (in this case: the proposition that the dying woman’s son is fine), they do not take on a commitment, and thus they do not take on a responsibility to provide a strong defence of it. The misleader does have to provide a weak defence of the believed-false proposition. But as commitment is tied to strong justificatory responsibility, misleaders avoid commitment to something they believe to be false. Is this picture of the lying-misleading distinction plausible? We think it is.

On the one hand, there is an intuitive sense in which the choice between lying and misleading in the examples above is a choice between putting forward a believed-false proposition in a committal way and putting it forward in a non-committal way. For instance, it seems intuitively right that the doctor in our initial example appears to take on a commitment to the dying woman’s son being fine if she utters (1) (‘He’s fine’), while she appears to avoid this commitment if she utters (2) (‘I saw him yesterday and he was fine’). In many cases, communicative agents choose to mislead precisely because they see this as a way to avoid committing themselves to something they believe to be false.

On the other hand, patterns of legitimate challenges support this intuitive difference. If the doctor utters (1), she can be legitimately challenged in a strong way, e.g. with:

- (17):

What makes you sure he is fine?

By contrast, this challenge would be too strong, and thus illegitimate, following her utterance of (2); accordingly, the doctor could consistently dismiss the challenge without answering the question posed (‘I never claimed that he is fine’). At the same time, a weaker challenge, such as e.g. (18), would be legitimate in response to (2), and thus could not be dismissed:

- (18):

What makes you think that he is still fine?

So, this pattern of legitimate challenges aligns nicely with the patterns found with constatives of different force. Here it is important that we are only looking at the legitimacy of the challenges in view of the speech-act that is being challenged (see above). The wording of the challenge is important, too. The fact that, having uttered (2), the doctor can consistently dismiss a strong challenge, such as (17), does not mean that there is nothing to call the speaker out on. There are certainly related challenges in the vicinity that the doctor could not consistently dismiss. For example, she could not dismiss a challenge pointing out that her utterance of (2) was insincere.

In our view, these are good reasons to think that the difference in commitment between lying and misleading aligns with the difference in commitment between assertion and weaker constatives. Are there any reasons to doubt this picture? It might be argued that the commitment-based account arrives at a too demanding view of what it is to lie, and that it misclassifies lies that do not involve commitment.Footnote 14 A worry of this kind has been raised by Don Fallis (2009: 49), who discusses a case in which a witness utters:

- (19):

Tony was with me at the time of the murder. Of course, you know I am really bad with dates and times.

The witness believes that Tony was not with him at the time of the murder. Has he lied? Fallis holds that although (19) intuitively is a lie, it is not classified as such by the commitment-based account, as the witness avoids taking on the required commitment through hedging his utterance.

We think that although hedged utterances raise interesting questions in the debate on how to define lying, they are not a particular problem for the commitment-based account just presented. For one thing, there is the question of how effective the hedge is. It could well be the case that the witness takes on a commitment to Tony being with him at the time of the murder despite adding the second sentence. In that case, however, the commitment-based account would classify (19) as a lie (cf. Carson 2010: 38 for a similar remark).

Secondly, even if the witness does avoid committing himself to Tony being with him at the time of the murder, there may be other propositions he nonetheless commits himself to and believes to be false. For example, it seems plausible that through uttering (19), the witness commits himself to not being sure about whether Tony was with him at the time of the murder, although he is sure about this matter.Footnote 15 In this case, (19) would be a lie even if the witness did manage to avoid commitment to the proposition expressed by the first sentence.

Thirdly, if hedged utterances were indeed a problem for the commitment-based view, they would arguably be a problem for most recent definitions of lying. After all, it is widely held that lying requires asserting. It is also uncontroversial that a hedge can prevent an utterance from being an assertion. So, if the commitment-based view misclassified such cases, the same appears to hold for all assertion-based definitions of lying. This indicates that hedged utterances should not be seen as a reason against the commitment-based account. Rather, they form an interesting class of examples that comes into view through considering the role of commitment in lying. Certainly, this class of examples requires further investigation that, however, would take us too far afield in the current context.

All in all, we believe that the case for a difference in commitment between lying and misleading is strong. The account of this difference we have sketched still leaves many questions open. For example, standard cases of misleading involve conversational implicatures. Which conversational implicatures can be used to avoid commitment? And how can implicatures be employed to avoid commitment?Footnote 16 For present purposes, these questions can remain unanswered. What matters here is that lying and misleading do plausibly differ in terms of commitment (regardless of how exactly that notion is spelled out), and thus differ in a way that goes beyond what is said.

4 How the difference in commitment can make a moral difference

Having argued that lying and attempted misleading differ in terms of commitment, we now want to show that this difference can be relevant for their overall moral assessment. But it can be relevant in different ways: the very same feature that makes it possible that lying is better in some cases is also responsible for its being worse in others, and is irrelevant in yet others. How can that be? In order to answer this question, let us go through the cases outlined above in detail and see how the difference in commitment accounts for the different assessment.

4.1 Choosing the safer option

In the case of Kant’s murderer (case 5) and in the case of the willingly deceived cook (case 6) it is easiest to detect the reason for a moral difference between lying and misleading. In both cases, the communicative agent has an obligation to leave the addressee in the dark about the truth, although for different reasons. In the case of the murderer, it is the good of the potential victims that calls for deceiving him; in the case of John, the willingly deceived cook, it is not the good of someone else, not even the good of John himself, that demands his deception; rather, it is his right to decide for himself about his epistemic states, his epistemic authority if you wish, that has to be respected. At any rate, it seems safe to say that deceiving is required in both cases. But if so, we should expect the more reliable means to the intended deception to be preferable.

This is where the difference in commitment comes in, which can lead to a difference in deceptive reliability between lying and misleading. In many cases, it will be the case that a straightforward lie is the more reliable means of deception (cf. Adler 1997: 439). Why so? Because by answering in a non-committal way we open up a gap between what we commit ourselves to and what we mean to communicate. This may then make the addressee wonder about our reasons for doing so: Why is the speaker avoiding commitment? Why doesn’t she take on a strong justificatory responsibility? And one answer to this is that she is unable to provide the required defence. A misleading response might therefore, precisely in virtue of its non-committal nature, give rise to suspicion that would be avoided by a plain lie. So, it is the non-committal nature of misleading (as opposed to lying) that makes it the less reliable means to deceive the other side under standard conditions. This is not to rule out the possibility that sometimes misleading is the safer option. For example, this may happen when you are in danger of revealing yourself because you are not used to lying (you tend to blush when lying, say). But in the absence of such contingent circumstances, which are not grounded in the natures of lying and misleading, misleading is usually the less reliable option.Footnote 17

It may be objected that reliability only gives us an instrumental reason to favour lying over misleading in certain cases, but not a moral reason to do so. On this reasoning, we may have decisive moral reason to deceive the addressee, but not to deceive her one way rather than the other. Against this view, we claim that lying is not only the more reliable action to achieve a given aim, but also the morally preferable action (in the cases at issue). This is shown by the fact that choosing the course of action that someone takes to be less reliable is subject to blame or moral criticism and not just to rational criticism. What we would say to someone who chooses the less reliable option is not just that he is foolish or irrational, but that what he did was careless and negligent. This indicates that there is in fact a moral obligation to choose the most reliable course of action given that it is morally obligatory to pursue a certain goal. It is therefore correct to say that in some cases, the nature of lying as the more committal speech act gives us a moral reason to favour lying over misleading.

4.2 Leaving a path to the truth

While the difference in reliability makes lying better than misleading in cases 5 and 6, there are also cases in which the difference in reliability between the two means of deception makes lying worse than misleading, as we now want to argue.

It is our assumption that, at least in certain contexts, we have a fundamental claim to truthfulness over matters that are of our immediate concern. For instance, the Argentinian Madres de Plaza de Mayo have a claim to truthful answers to their questions about what happened to their sons and daughters who disappeared under the Argentinian military dictatorship. But also in more mundane cases, we have a right to a truthful answer when asking, e.g., for the way to the lecture theatre. On the other hand, there is of course no right to know about the personal details of other people’s lives (unless they stand in a particular relationship with us). It is a complicated question where the claim to truthfulness ends. However, it appears right to say that in ordinary contexts, with no special conditions obtaining, we do have a right to be told the truth (as the other party sees it). This holds independently of any particular moral theory. On the contrary, every reasonable moral theory had better be able to make room for the claim to truthfulness.

How does the idea of a claim to truthfulness, in connection with the commitment-based distinction between lying and misleading, help to understand why misleading can be preferable to lying? In a situation where there is uncertainty over whether the claim to truthfulness has been released, as is the case in our example of Bill and Amy (case 2), it seems advisable to leave the door open for him who really wants to know the truth. And misleading, rather than lying, is just a way of doing this. If Amy were to lie to Bill, he would have no chance of finding out Amy’s true opinion (unless he had other reasons to doubt her sincerity); by committing to her liking the picture, Amy had in a way closed the door for further inquiry. If, however, Amy avoids commitment by choosing a misleading utterance, such as our sentence (4), she leaves open the possibility (for someone who ‘has ears to hear’) to find out the truth.Footnote 18 Of course, if Bill was more interested in flattering remarks than in Amy’s actual reaction to the pictures, he will be satisfied with her answer; but then, again, Amy will have made no mistake, because she only led into deception someone who was not interested in her honest opinion in the first place.

So, again, it is the difference between lying and misleading in terms of commitment that plays the pivotal role, but in this case that difference points in the opposite direction: in virtue of its non-committal nature, misleading is, ceteris paribus, the less reliable option and comes with a potential of being found out; in the current case, in which the agent is uncertain about whether the addressee’s claim to truthfulness is active, this provides a reason to mislead rather than lie, given that the potential to be found out is a morally worthwhile feature.

While the claim to truthfulness sets apart lying and misleading in some cases, there are other cases in which it plays no role at all. Among these are cases 5 and 6: it seems plausible to say that both the murderer and the willingly deceived cook have lost their claim to truthfulness (with respect to the matter at hand), albeit for different reasons. The murderer has lost his claim to truthfulness on account of his evil intentions; the willingly deceived cook has implicitly refrained from asserting that right by his own behaviour. There is thus no claim to truthfulness the respective communicative agents have to consider in choosing between lying and misleading, and the same goes for cases where that claim has explicitly been given up. (Still, the difference in commitment can be morally relevant for other reasons, as we have argued above).

How about cases 3 (The Peanut Attack) and 4 (Paul and Paula), in which there is no intuitive moral difference between lying and misleading? Here, the addressees (Frieda in case 3 and Paul in case 4) have not lost their claim to truthfulness, as the communicative agents are aware. But in case 3, both utterances (‘There are no peanuts in the meal’ and ‘I didn’t put any peanuts in’) are equally reliable as means of deception. After all, both utterances are direct answers to Frieda’s imprecise question (‘Did you put any peanuts into the meal?’). As a result, Frieda is not in a position to detect the lack of commitment in George’s misleading answer. Had Frieda asked more carefully (e.g. ‘Are there any peanuts in the meal?’), then the second answer might have aroused suspicion. This shows that even though lying and misleading always differ in terms of commitment (as we have argued), this difference in commitment does not always lead to a difference in reliability, in which case it cannot always set lying and misleading apart morally.

In case 4, however, we can assume that there is a difference in reliability: Paul suspects that Paula is having an affair, so he might well pay close attention to what exactly she commits herself to. Given that Paul has a claim to truthfulness, doesn’t this give Paula a reason to prefer misleading over lying? The answer is no, for if Paula took Paul’s claim to truthfulness as a genuine reason in her deliberative situation, she would have to conclude that what she should do is simply tell the truth. What the claim to truthfulness demands in this situation (where no conclusive reasons oppose truth-telling) is not misleading rather than lying, but speaking the truth.

The foregoing considerations make clear that the claim to truthfulness cannot be used to ground a general moral preference for misleading over lying, as has been attempted e.g. by Adler (1997, 2018). Even if there is a general claim to truthfulness in ordinary contexts, there are cases in which addressees forfeit this claim. And there are yet other cases in which, although the claim is not forfeited, it cannot play a role in the deliberative processes of choosing a means of deception. In all of these cases, the claim to truthfulness does not give misleading a moral advantage over lying.Footnote 19

4.3 Acknowledging the claim to truthfulness

We have argued that the difference in commitment accounts for the fact that lying is better than misleading in some cases (Kant’s murderer and the willingly deceived cook, cases 5 and 6) and worse in others (Bill and Amy, case 2). In each of these cases, choosing a misleading utterance puts the addressee in a position to detect a lack of commitment and thus to uncover the attempted deception. But it seems that there could be a moral difference between lying and misleading even if the latter option does not put the addressee in a position to detect a lack of commitment and the two options are equally reliable. This happens e.g. in the case of the dying woman (case 1): the doctor should attempt to mislead (by uttering ‘I saw him yesterday and he was fine’), even if she thinks that the dying woman will not press her for a more committal answer, i.e. even if she takes lying and misleading to be equally reliable. Why? Because in doing so, she expresses that she acknowledges the dying woman’s claim to truthfulness (even while choosing not to fulfil it in order to spare her unnecessary pain).

That lying and misleading differ in an expressive way has been highlighted by Baumann (2015). According to Baumann, the choice to mislead (rather than to lie) can express two things: firstly, respect for the addressee (this is also noted by Adler 2018: 307), and secondly, the willingness to continue a trusting relationship with the addressee. We think it is right that, in some situations, communicative agents can express these things by choosing to mislead. However, we want to spell out the expressive differences between lying and misleading in a slightly different way, as we will now illustrate with the help of the case of the dying woman.

To begin with, note that in the case of the dying woman, the doctor’s choice of misleading cannot plausibly express a willingness to continue a trusting relationship—after all, the woman is about to die. That leaves Baumann’s first proposal, according to which the doctor’s misleading utterance expresses respect for the dying woman. Such an expression of respect seems more plausible in the current case. As Baumann notes, expressing respect for a person does not require that person to register the expression of respect; the doctor might thus express to others who are present (and possibly to herself) that she has respect for the dying woman. But why does the choice to mislead express respect for the dying woman? According to Baumann (2015: 20), choosing to mislead signals that the communicative agent treats the addressee as an ‘epistemic agent’ and signals an intention to respect the addressee’s autonomy.

We favour a different answer to this question. In our view, the choice to mislead expresses that the doctor acknowledges the dying woman’s claim to truthfulness, as the doctor avoids committing herself (vis-à-vis the dying woman) to something she believes to be false. But how does so avoiding commitment express acknowledgement of a fundamental claim to truthfulness even though misleading is no more likely to be detected than lying? Here is a tentative answer. Above, we argued that misleading differs from lying in terms of the force of the speech-act. In other cases, too, we find that we can express respect by choosing of two speech-acts with the same content the one that has lesser force. Take, e.g., requesting and commanding: when we request someone to get us a glass this will in general be much more respectful than if we command them to do so. Or take different ways of criticising someone: by cautiously indicating that we are not satisfied with someone’s work, we can express a kind of respect that an assertive, outright dismissal of the work surely cannot express. In a very similar manner, it seems, misleading as the less forceful act can be more respectful than lying. Of course, there is much more to be said on the connection between force and respect. For instance, it is an interesting question how the choice of a less forceful speech-act expresses respect. For reasons of space, we will have to set this question aside here. But given that there quite clearly is a connection between force and respect in many speech-acts, this provides at least an initial reason to hold that something of the kind applies to the lying-misleading distinction.

Here are two further reasons to think that the commitment-based explanation of the expressive difference between lying and misleading is attractive. Firstly, it grounds the expressive difference (which is morally relevant) in the theoretical difference in commitment. Such an undergirding is not immediately obvious in Baumann’s account. Secondly, it can offer a unified explanation of both of the expressive dimensions Baumann posits. Plausibly, one can express respect for someone by acknowledging their claim to truthfulness. And such an acknowledgement can also express willingness to continue a trusting relationship (if such a relationship exists and can be sustained).

Just as the previous differences, the expressive difference does not always set lying and misleading apart. If addressees have forfeited or released their claim to truthfulness, as in cases 5 and 6, acknowledging such a claim clearly cannot count in favour of misleading. And even if the addressee’s claim to truthfulness is active, communicative agents may not be able to express that they are acknowledging such a claim. In cases 3 and 4, for instance, the agents have decided without good cause to pursue a morally impermissible action that involves not honouring the addressee’s claim to truthfulness. No one who is aware that the choice to deceive is impermissible will take the choice to deceive through misleading to be an expression of an acknowledgement of the addressee’s claim to truthfulness. In line with this, it seems that the expressive difference only comes in when the deception is seen as morally permissible.

4.4 Tying the strands together

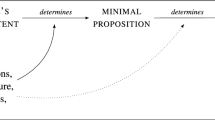

We have seen that the difference between lying, which requires a commitment to something the speaker believes to be false, and misleading, which involves no such commitment, can be relevant to their moral evaluation in (at least) three different ways. First, instrumentally, if one of them (standardly, lying) is the more reliable means to achieve the goal of deceiving the addressee; second, epistemically, if we do not know whether the other person prefers being deceived to an inconvenient truth; third, symbolically, insofar as misleading can serve to express an acknowledgement of the addressee’s claim to truthfulness in cases where deception is nevertheless the morally preferable option. In all these respects, it is the difference in commitment that makes a moral difference between lying and misleading possible (as can be seen in Fig. 1).

In saying this, we are not claiming that commitment is itself a (pro tanto) morally significant feature with a variable valence in the way affirmed by particularism, as if sometimes commitment speaks for a given action, sometimes against it. Rather, commitment is the distinguishing feature in the natures of lying and misleading that explains how the aforementioned features can affect their moral assessment in ways that result in different pro tanto choiceworthiness. Sometimes, the difference in commitment will affect the potential of being found out and thereby allow for a difference in the likelihood of harm or, in situations of epistemic uncertainty, leave a path to the truth; and sometimes it will make it possible to use the choice of misleading as the symbolic recognition of a claim to truthfulness.

Note that none of these features will always be morally significant. Obviously, sometimes neither misleading nor lying will be the more reliable option, and neither can be conceived as the expressive acknowledgement of a claim to truthfulness; in these cases, lying and misleading are morally on a par. For instance, in the case of the peanut attack (case 3) it seems that lying and misleading are equally reliable ways of leading Frieda into deception (practically, there is no difference with respect to Frieda’s chances of finding out about the peanuts), and that George cannot pretend to be acknowledging Frieda’s claim to truthfulness by misleading rather than lying. Accordingly, there is no moral difference between lying and misleading in this case: if George was to think about what the morally right thing to do is in this situation at all, he would have to conclude that he simply should neither lie to Frieda nor mislead her.

That does not mean that where those features are present and do bear moral weight, they are necessarily overriding. They can tip the balance when everything else is held fixed, as the examples 1–2 and 5–6 show; but when weightier considerations are present, they can be overridden. In other words, these features give us overridable pro tanto reasons only. For instance, we may have a reason to prefer lying over misleading (as it is the more reliable option), but misleading may be preferable to lying for other, more accidental reasons, as when someone promised the other never to tell a lie, where that promise itself may be thought to exert a certain normative force (cf. Saul 2012a: 98–99).

As a related point, the fact that the three features under consideration are independent of each other means, on the one hand, that they can add up; one might think that this is the case in the example of Bill and Amy where the uncertainty over Bill’s preferences gives Amy one reason to mislead (rather than to lie), while another reason could be thought to be generated by the wish to symbolically acknowledge his fundamental claim to truthfulness. On the other hand, the normatively relevant features can also point in different directions. For instance, we can slightly adapt the case of the dying woman. In this variation, lying is the somewhat more reliable way of deceiving the woman, but misleading is still the more suitable way of expressing respect for her claim to truthfulness. It is difficult to give a principled answer as to the question which option is preferable all things considered, which just proves the point in question: that both aspects, the instrumental and the symbolic one, bear independent pro tanto moral weight.

5 Conclusion

We have argued that the relationship between lying and misleading is complicated: in some cases, lying is in virtue of its nature worse than attempting to mislead, in other cases it is better, and in yet others there is no moral difference. In answering the question posed at the beginning of this paper, we thus have to decide on a case-by-case basis, while taking into account diverse considerations, including the reliability of the respective means of deception, the (defeasible) claim to truthfulness of the addressee and what is expressed by the choice to lie or to mislead. Such a multi-faceted answer might be perceived as unsatisfying and disunified. But we have tried to show that its advantages prevail.

To begin with, the apparent disunity is merely apparent. All three of the features that can set lying and misleading apart depend on one essential difference between lying and misleading: on a difference in commitment. It is because lying is the more committal means of deception that it is (standardly) more reliable than misleading; that it closes off the path to truth in situations of uncertainty about whether the addressee wishes to release her claim to truthfulness; and that the choice of misleading can be an expression of respect for the addressee. So, in fact, the features we appeal to are closely connected. We wish to leave open the possibility that there are further features that can make for a moral difference between lying and misleading, but we take the features mentioned to be particularly important as they are bound to the natures of lying and misleading.

Furthermore, a pluralist answer does much better than the two main positions in the debate at capturing pre-theoretical intuitions. Those two main positions are the traditional view that lying is generally worse than misleading (except in certain special cases) and the more recent view of Williams and Saul, according to which lying and misleading are generally on a par (except in certain special cases). Both of the main views have to ascribe widespread error in our moral judgements, as we have tried to make apparent: it is neither the case that lying (almost) always appears to be worse than misleading; nor is it the case that both options (almost) always appear to be on a par. Quite to the contrary, given the pre-theoretical intuitions about the matter, we should expect the relationship between lying and misleading to be complicated. And in our view, it is complicated. Complicated, but not intractable.

Notes

A third general answer is defended by Rees (2014), who argues that lying is in virtue of its nature better than misleading. Except in special cases, we should choose to lie rather than to mislead. To keep things manageable, we will not discuss Rees’s view in this paper, though it should be apparent how it is affected by the considerations to follow.

As Saul (2012a: 71f.) helpfully points out, ‘misleading’ is a success term, while ‘lying’ is not. The important comparisons are thus between lying and attempting to mislead, as well as between successful lying and misleading. We will focus on the comparison between lying and attempting to mislead, as this is the comparison that matters from the deliberative perspective (more on that notion shortly). Saul also rightly notes that lying must be intentional, while misleading may be unintentional. This asymmetry does not hold for the comparison of lying and attempting to mislead, as an attempt to mislead has to be intentional. In what follows, we will mostly use ‘mislead’ instead of the more cumbersome ‘attempting to mislead’. In discussing attempts to mislead we wish to leave open whether or not the attempt is successful.

See e.g. Saul (2012a: 70) for discussion of this case.

Throughout this paper, we are comparing cases of lying about p with corresponding cases of attempting to mislead someone about p; in other words, the content about which the agent intends to deceive the addressee remains constant. On lying about ascriptions, see Holton (2019).

Firstly, we have reduced the seriousness of harm George wants to inflict on Frieda, as this aspect of the original example might be taken to interfere with intuitions about the choice of lying and misleading (as is argued e.g. by Berstler 2019: Section 5.1). Secondly, we have modified the utterances to ensure that (5) is clearly false while (6) is clearly true. The original example relies on the controversial view that putting peanut oil in a meal does not constitute putting peanuts in a meal.

Strudler (2010: 177) mentions that lying and misleading are on a par in contexts of ‘maximal trust’, when both options are maximally wrong.

Several theorists, including Carson (2006) and Saul (2012a: 10–12) herself, have argued that lying involves committing to (or warranting) something believed to be false. However, these theorists do not hold that lying and misleading differ in terms of commitment; rather, they take the essential difference between lying and misleading to concern what is said. Viebahn (2017, 2019, 2020) argues that commitment is the central difference between lying and misleading. Also see Cohen (2018), who argues that misleading leads to a lower warrant of truth than lying.

The distinction between content and force applies not only to constative speech-acts, but also to speech-acts of different kinds. For example, directive speech-acts of requesting and commanding could share the same content while differing in force. A helpful account of the force-content distinction is provided by Green (2017).

For more extensive considerations along these lines, see Viebahn (2020).

It is arguably possible to mislead through conjecturing and thereby implicating something believed to be false: in that case, the speaker neither takes on a commitment to the conjectured proposition, nor to the implicated proposition.

Many thanks to an anonymous referee for pressing us on this point.

There are also cases in which lying and misleading are equally reliable as a means of deception, as we will argue below. Cohen (2018) argues that because lying is (standardly) more reliable than misleading, the breach of trust involved in lying is (standardly) greater than the breach of trust involved in misleading. According to Cohen, lying is thus standardly worse than misleading, though sometimes they are morally on a par (as sometimes lying and misleading are equally reliable). We agree with Cohen that lying is standardly more reliable than misleading as a means of deception; however, we hold that this can also make lying better than misleading, and we do not hold that the moral difference has to do with a difference in the level of trust that is breached (though for reasons of space we will not argue against Cohen’s view on this matter).

A related but distinct point is made by Strudler (2010: 176–179). Strudler argues that misleading gives the addressee more options than lying because it is easier to express doubt about something that has been implicated than about something that has been directly expressed. However, Strudler only considers cases in which the addressee has independent reasons to doubt the truthfulness of the speaker. He does not argue that attempted misleading (but not lying) can give the addressee a chance to find out that the speaker is not being truthful.

We agree with the criticism of Saul (2012a: 84–86), according to which there is no good reason to hold that a norm of (or claim to) truthfulness applies to implicatures to a lesser extent than it applies to assertions. If there is such a norm (which we take to be plausible), it arguably applies to what the speaker intends to communicate. However, our objections to Adler’s approach are independent of the objections put forward by Saul.

References

Adler, J. (1997). Lying, deceiving, or falsely implicating. The Journal of Philosophy, 94, 435–452.

Adler, J. (2018). Lying and misleading: A moral difference. In E. Michaelson & A. Stokke (Eds.), Lying. Language, knowledge, ethics, and politics (pp. 301–317). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baumann, H. (2015). Gibt es einen moralisch relevanten Unterschied zwischen Lügen und Irreführen? Zeitschrift für praktische Philosophie, 2, 9–36.

Berstler, S. (2019). What’s the good of language? On the moral distinction between lying and misleading. Ethics, 130, 5–31.

Brandom, R. (1983). Asserting. Noûs, 17, 637–650.

Carson, T. (2006). The definition of lying. Noûs, 40, 284–306.

Carson, T. (2010). Lying and deception: Theory and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chisholm, R. M., & Feehan, T. D. (1977). The intent to deceive. The Journal of Philosophy, 74, 143–159.

Cohen, S. (2018). The moral gradation of media of deception. Theoria, 84, 60–82.

Davis, W. (2019). Implicature. In: E. N. Zalta (Ed.) The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/implicature/. Accessed 12 June 2020.

Fallis, D. (2009). What is Lying? The Journal of Philosophy, 106, 29–56.

Fricker, E. (2012). Stating and insinuating. Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume, 86, 61–94.

Green, M. (2009). Speech acts, the handicap principle and the expression of psychological states. Mind and Language, 24, 139–163.

Green, M. (2017). Speech acts. In: E. N. Zalta (Ed). The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/speech-acts/. Accessed 12 June 2020.

Holton, R. (2019). Lying about. The Journal of Philosophy, 116, 99–105.

Kant, I. (1996). Practical philosophy. Ed. and trans. Mary J. Gregor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Quoted after the edition of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

Kölbel, M. (2011). Conversational score, assertion and testimony. In J. Brown & H. Cappelen (Eds.), Assertion (pp. 49–78). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2011). What is assertion? In J. Brown & H. Cappelen (Eds.), Assertion (pp. 79–98). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Montminy, M. (2020). Testing for assertion. In S. Goldberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of assertion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peirce, C. S. (1934). Judgment and assertion. In: Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vol. V, pp. 385–387). Boston: Harvard University Press.

Pepp, J. (2020). Assertion, lying, and untruthfully implicating. In S. Goldberg (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of assertion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Plato. (2004). The Republic. Trans. C.D.C. Reeve. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Rees, C. F. (2014). Better lie! Analysis, 74, 59–64.

Rescorla, M. (2009). Assertion and its constitutive norms. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 79, 98–130.

Saul, J. M. (2012a). Lying, misleading, & what is said. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saul, J. M. (2012b). Just go ahead and lie. Analysis, 72, 3–9.

Searle, J. R. (1979). Expression and meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stokke, A. (2016). Lying and misleading in discourse. Philosophical Review, 125, 83–134.

Strudler, A. (2010). The distinctive wrong in lying. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 13, 171–179.

Turri, J. (2010). Epistemic invariantism and speech act contextualism. Philosophical Review, 119, 77–95.

Unger, P. (1975). Ignorance. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Viebahn, E. (2017). Non-literal lies. Erkenntnis, 82, 1367–1380.

Viebahn, E. (2019). Lying with presuppositions. Noûs: Early View.

Viebahn, E. (2020). The lying-misleading distinction: a commitment-based approach. Unpublished manuscript.

Webber, J. (2013). Liar! Analysis, 73, 651–659.

Williams, B. (2002). Truth and truthfulness: An essay in genealogy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank an anonymous referee for this journal, the departmental colloquium at the Department of Philosophy at the University of Zurich, Olaf Müller’s colloquium at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Paulina Sliwa and Derya Yürüyen for very helpful comments and suggestions. Both authors contributed equally to this paper. Open access funding for this article was provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Timmermann, F., Viebahn, E. To lie or to mislead?. Philos Stud 178, 1481–1501 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01492-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01492-1