Abstracts

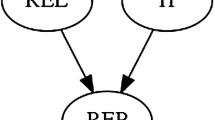

This paper distinguishes bruteness from fundamentality by developing a theory of stochastic grounding that makes room for non-fundamental bruteness. Stochastic grounding relations, which only underwrite incomplete explanations, arise when the fundamental level underdetermines derivative levels. The framework is applied to fission cases, showing how one can break symmetries and mitigate bruteness whilst avoiding arbitrariness and hypersensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In addition to boundary conditions, the laws that connect causes to what they cause and grounds to what they ground might not admit of explanation. However, we can set laws aside. Either one is operating with a robust conception of laws, i.e. a non-reductionist approach that treats causation and grounding as generative and as governed by laws, in which case they stand outside the fundamentality hierarchy/causal order and are not apt for being grounded, i.e. they are autonomous (in Dasgupta’s 2016 terminology). Or, if laws merely describe patterns of causation/grounding, then they can be explained.

Stochastic explanations are widely recognised in the case of causation, yet rejected in the case of grounding: “When it comes to metaphysical ground …the very idea of a probabilistic connection makes no sense” (Rosen 2017: 281). This is seen as an important disanalogy between causation and grounding. The theory of probabilistic grounding removes this disanalogy, bringing causation and grounding more closely together.

Probabilities are construed as objective chances in line with propensity interpretations.

Cf. “Conditional grounding” (Bader: manuscript) for an account of conditional grounding that only underwrites conditional necessitation.

The only necessitation principles that one can accept in the context of stochastic grounding are: if Γ grounds X then \(\square (\Gamma \to {\text{P}}\left( {\text{X}} \right) > 0)\), and: if Γ grounds X then \(\square \left( {\left( {\Gamma \wedge \neg \Delta } \right) \to {\text{X}}} \right)\).

Γ can be both a complete immediate ground and an incomplete mediate ground of X. If \({\text{X}} = {\text{Y}} \vee {\text{Z}}\) where Y is a stochastic ground of Z, then Y can both immediately deterministically ground X and stochastically ground Z which deterministically grounds X, thereby rendering Y a mediate stochastic ground of X. (This is analogous to how a disjunction can be both fully and partially grounded in Γ if absorption principles fail, and how Γ can be both a mediate conditional ground and an immediate unconditional ground of the same fact.).

Cf. Humphreys (1989) for a very helpful account of probabilistic explanation that has the form ‘X because of \(\upphi\), despite \(\uppsi\)’.

Since X fails to be grounded in any of its contributing grounds iff some incompatible outcome Y is grounded by some opposing ground, the probability of the disjunction of the different outcomes that have contributing grounds, e.g. X \(\vee\) Y, is = 1. The probability that some contributing ground of X succeeds in grounding X is the complement of the probability that some contravening ground succeeds in grounding an incompatible outcome Y.

This is analogous to how c can be a deterministic cause of e in one context, yet only a probabilistic cause of e in a different context in which contravening factors are present.

For an account of how underdetermination, indeterminacy and bruteness interact, cf. “Coincidence and supervenience” (Bader: manuscript).

Standard bilocation approaches consider the original person to persist as a scattered object. Non-standard approaches consider persons to be higher-order entities that allow for non-unique manifestations, such that A, B and C are different manifestations of the same higher-order entity. A non-unique manifestation relation allows for identity at the level of the higher-order entity, without identity at the level of the manifestations. A fission scenario then involves one person that has a single manifestation, namely A, prior to fission, yet two distinct manifestations, namely B and C, subsequent to fission. (Thanks to Mark Johnston for helpful discussions.).

In response one might try to revise the logic of identity. Gallois (1998), for instance, allows for occasional identities by rejecting the requirement that transitivity holds across time. This approach, however, gives rise to intra-temporal transitivity violations (cf. Bader 2012). Alternatively, one might deny that persistence is a matter of identity. Instead of operating with a trans-temporal identity relation, stage theory accounts for temporal predication in terms of temporal counterpart relations (cf. Sider 2001; Hawley 2001). One-many counterpart relations allow A to persist as both B and C. A will be in room 1 at \({\text{t}}^{\prime }\) since A has a temporal counterpart, namely B, in that room at \({\text{t}}^{\prime }\), and A will be in room 2 at \({\text{t}}^{\prime }\) since A has a temporal counterpart, namely C, in that room at \({\text{t}}^{\prime }\). Yet, A will not be in both rooms since A does not have a temporal counterpart that is in both rooms. To ensure that these temporal predications cannot be agglomerated, stage theorists have to insist that the counterpart relations underwriting these two predications differ, yet symmetric fission cases are precisely ones where the relation between A and B is the same as that between A and C (cf. Bader (2016) for a critique of one-many counterpart relations).

This problem arises on all the traditional accounts of intrinsicness, including duplication, combinatorial, and hyperintensional approaches.

The ‘only x and y rule’ runs into difficulties due to maximality conditions. These can be addressed by a theory of conditional intrinsicness, cf. “Relativised intrinsicality” (Bader: manuscript).

“The paradox is not dealt with by …changing the subject, ceasing to talk seriously about personal identity, and instead talking about what matters to us in survival” (Johnston 1989: 377).

This approach locates indeterminacy in the world, namely in the identity relation, and is not to be confused with locating indeterminacy in the concept of a person. Cf. “When a case necessarily violates some principle relatively central to our conception of persons and their identity over time, the concepts of a person and of being the same person over time may not determinately apply in the case, so that there may be no simple fact about personal identity in that case” (Johnston 1992: 603; also cf. Williamson 1990: 119–120).

The bilocation approach, which denies that there are two persons post-fission and instead considers A to persist as B and C taken together, i.e. \({\text{A}} = {\text{fu}}\left( {{\text{B}},{\text{C}}} \right)\), is also incompatible with standard versions of intrinsicness. One can, however, argue that persistence is conditionally intrinsic by claiming that persistence is grounded in the intrinsic features of certain processes, conditional on the processes being maximal. Proponents of bilocation consider the R-relation to be an equivalence relation. The maximal process in a fission case is thus the Y-shaped process connecting A to B and C taken together. The processes connecting A to B and A to C are, accordingly, sub-maximal. Although their duplicates, which connect \({\text{A}'}\) to \({\text{B}'}\) and \({\text{A}''}\) to \({\text{C}''}\), preserve identity, conditional intrinsicality does not imply that A = B and A = C, since only processes satisfying the maximality condition have to agree in terms of preserving identity. (Thanks to Mark Johnston for helpful discussions.).

Although there are no sufficient conditions in branching cases but only probabilistic grounding connections, there are necessary conditions. For instance, the disjunction of all possible contributing grounds is a necessary condition. As Williamson notes, “[o]nce the claim of sufficiency is withdrawn, the cases of fission and fusion present no obstacle to the claim of necessity” (Williamson 1990: 117).

Even though the fact that Γ obtains is an incomplete explanation of x’s being F, that Γ grounds x’s being F is a complete explanation of x’s being F.

This is a generalisation of the hyperintensional account developed in Bader 2013.

Closure will fail if the contributing grounds of F are intrinsic yet the contravening grounds that, if successful, ground not-F are extrinsic. F would be intrinsic yet its negation not-F extrinsic.

“Identity is utterly simple and unproblematic. Everything is identical to itself; nothing is ever identical to anything else except itself. There is never any problem about what makes something identical to itself; nothing can ever fail to be. And there is never any problem about what makes two things identical; two things never can be identical” (Lewis 1986: 192–193).

This does not violate the necessity of identity since the person on the C-branch in the fission case (namely the new person) is not identical to the person on the C-branch in the non-branching case (namely the original person), cf. Garrett (1990: section 6).

This counterfactual involves backtracking reasoning.

This only works for some versions. Nozick considers four options. Only option 1, which understands persistence in terms of the path of closest continuation, can be stated in this way. Options 2–4, which allow for ‘jumps’, are extrinsic in an objectionable way (cf. Nozick 1981: 42–43).

To avoid the counter-intuitive result that there were two persons prior to fission, this approach is usually combined with a revisionist semantics, whereby one does not count in terms of identity. Robinson (1985), for instance, suggests counting by constitution rather than identity.

Whilst non-branching theories consider the asymmetry to be irrelevant as regards identity, it can be significant for survival, which is a matter of degrees.

There will hence be failures of supervenience: duplicate asymmetric fission cases can differ in persistence facts.

If contributing grounds were to differ not only in number but also in strength, then there would be different ways of ending up with asymmetric probabilities. Such an approach, however, would build probabilities into the grounds rather than deriving probabilities from the interaction amongst opposing grounds.

References

Bader, R. M. (2012). The non-transitivity of the contingent and occasional identity relations. Philosophical Studies, 157, 141–152.

Bader, R. M. (2013). Towards a hyperintensional theory of intrinsicality. The Journal of Philosophy, 110(10), 525–563.

Bader, R. M. (2016). Contingent identity and counterpart theory. Philosophical Perspectives, 30, 7–20.

Dasgupta, S. (2016). Metaphysical rationalism. Noûs, 50(2), 379–418.

Gallois, A. (1998). Occasions of identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Garrett, B. (1988). Identity and extrinsicness. Mind, 97(385), 105–109.

Garrett, B. (1990). Personal identity and extrinsicness. Philosophical Studies, 59, 177–194.

Hawley, K. (2001). How things persist. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hawley, K. (2005). Fission, fusion and intrinsic facts. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 71(3), 602–621.

Hitchcock, C. (2004). Do all and only causes raise the probabilities of effects? In J. Collins, N. Hall, & L. A. Paul (Eds.), Causation and counterfactuals (pp. 403–417). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Humphreys, P. (1989). The chances of explanation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Johnston, M. (1989). Fission and the facts. Philosophical Perspectives, 3, 369–397.

Johnston, M. (1992). Reasons and reductionism. The Philosophical Review, 101(3), 589–618.

Lewis, D. (1986). On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

McGrath, M. (2007). Four-dimensionalism and the puzzles of coincidence. Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, 3, 143–176.

Nozick, R. (1981). Philosophical explanations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robinson, D. (1985). Can amoebae divide without multiplying? Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 63(3), 299–319.

Rosen, G. (2017). Ground by law. Philosophical Issues, 27, 279–301.

Schaffer, J. (2000). Overlappings: Probability-raising without causation. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 78(1), 40–46.

Sider, T. (2001). Four-dimensionalism: An ontology of persistence and time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sider, T. (2011). Writing the book of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wiggins, D. (1980). Sameness and substance. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers.

Williamson, T. (1990). Identity and discrimination. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishers.

Zimmerman, D. (1998). Criteria of identity and the ‘identity mystics’. Erkenntnis, 48, 281–301.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Fatema Amijee, Theron Pummer, Katherine Hong, Gonzalo Rodriguez-Pereyra, an anonymous referee, and the participants of my graduate seminar on hyperintensional metaphysics at Princeton.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bader, R. The fundamental and the brute. Philos Stud 178, 1121–1142 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01486-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01486-z