Abstract

This paper develops a contextualist account of certain recalcitrant embedding phenomena with epistemic modals. I focus on three prominent objections to contextualism from embedding: first, that contextualism mischaracterizes subjects’ states of mind; second, that contextualism fails to predict how epistemic modals are obligatorily linked to the subject in attitude ascriptions; and third, that contextualism fails to explain the persisting anomalousness of so-called “epistemic contradictions” (Yalcin 2007) in suppositional contexts. Contextualists have inadequately appreciated the force of these objections. Drawing on a more general framework for implementing a contextualist theory (Silk 2016a), I argue that we can derive the distinctive embedding behavior of epistemic modals from a particular contextualist interpretation of a standard semantics for modals, general mechanisms of local interpretation, and typical features of discourse contexts. Examining embedding phenomena with epistemic modals raises difficult broader issues about conventionalization and pragmatic reasoning, the varieties of context-sensitive language, and the roles of context in interpretation. The paper concludes by briefly examining how the proposed contextualist account compares with certain relativist/expressivist accounts.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

An important function of language is to share and coordinate our attitudes in communication. In inquiry we manage our beliefs about how things are, how they might be, and how possibilities may hang together. Suppose we are investigating a murder. Our evaluation of (1) depends on what our evidence is like, as reflected in (2).

(1) | The butler might be the killer. | |

(2) | A: | The butler might be the killer. |

B: | Yeah, we can’t rule him out. We still need to see if his alibi checks out. | |

B′: | No, it can’t be him. It must have been the gardener; I saw him lurking around just before the crime. | |

Epistemic uses of modal verbs (“epistemic modals”) like those in (1)–(2) can also be used in characterizing one another’s states of mind, as in (3).

-

(3)

A thinks the butler might be the killer.

Such uses of epistemic language are commonplace. How to capture them is not.

Some theorists claim that the dependence of our evaluation of (1) on what information we accept derives from a dependence of the interpretation of (1) on a contextually relevant body of information. A prominent approach—call it contextualism—treats such sentences with epistemic modals as semantically context-sensitive in the same kind of way as sentences with paradigm context-sensitive expressions like ‘here’, demonstratives, pronouns, etc. In a context where Anna is most salient, (4) conventionally conveys that Anna won a medal; in a context where Betty is most salient, (4) conventionally conveys that Betty won a medal.

-

(4)

She won a medal.

Likewise, according to contextualism, in a context where Annette’s information \(i_A\) is relevant, (1) conveys (roughly) that \(i_A\) is compatible with the butler’s being the killer; but in a context where Ben’s information \(i_B\) is relevant, (1) conveys (roughly) that \(i_B\) is compatible with the butler’s being the killer. The semantic content of (1), and whether it is true or false, depends on what information is relevant in the discourse context, just as the semantic content of (4), and whether it is true or false, depends on what female is most salient in the discourse context. (We will refine this characterization of contextualism more precisely in due course.)

Assimilating the context-sensitivity of epistemic modals to that of paradigm context-sensitive expressions may seem to afford an attractive diagnosis of discourse-oriented uses like in (2). Yet serious objections have been raised. There are two main classes of data that have been thought problematic: first, discourse phenomena involving (dis)agreement; second, the behavior of epistemic modals in various complex linguistic environments, such as in attitude ascriptions and conditionals. Which is to say: epistemic modals are happy (=contextualist-friendly) neither embedded nor unembedded. Many theorists appeal to the distinctive discourse properties and embedding behavior of epistemic modals to motivate revising the compositional semantics or postsemantics. Though these theories differ in their details, they agree in distinguishing the context-sensitivity of epistemic modals from that of paradigm context-sensitive expressions. Even those who wish to maintain a contextualist semantics often do so by resorting to ad hoc pragmatic principles.

This paper focuses on three prominent objections to contextualism from embedding: first, that contextualism mischaracterizes subjects’ states of mind; second, that contextualism fails to predict how epistemic modals are obligatorily linked to the subject in attitude ascriptions; and third, that contextualism fails to explain the persisting anomalousness of so-called “epistemic contradictions” (Yalcin 2007, 2011) in suppositional contexts (Sect. 2). Drawing on a more general framework for implementing a contextualist theory (Silk 2015a, 2016a, b), I argue that we can capture the relevant embedding phenomena with epistemic modals with a static contextualist semantics and general, independently motivated principles of local interpretation and pragmatic reasoning (Sect. 3). This should be of interest to theorists who are compelled by the thought that the interpretation of epistemic modals depends, in some sense, on context, but who have reservations about innovations introduced by relativist, expressivist, or dynamic accounts. I conclude by briefly examining how the proposed contextualist account compares with certain relativist/expressivist accounts (Sect. 4).

For concreteness I will focus on epistemic modal auxiliaries of possibility and necessity (‘may’, ‘might’, ‘must’, etc.). But it’s important to remember that epistemic modal verbs are members of a broader class of epistemic vocabulary—what Swanson (2011) calls “the language of subjective uncertainty.” Further, the objections considered in this paper aren’t the only challenges that arise concerning epistemic vocabulary in embedded contexts. Though I think there are well-motivated ways of extending the proposed framework , I won’t argue for that here. The account in this paper should give a flavor for the kinds of explanatory resources available to contextualist theories.Footnote 1

Our question is whether bare (unmodified) epistemic modal clauses, like in (1)–(3), can be given a successful contextualist semantics.Footnote 2 I would like to make two preliminary remarks on the relevant sense in which contextualism treats epistemic modals as context-sensitive. First, contextualists sometimes motivate their views by noting that many modal verbs can have different “readings” in different contexts. For example, ‘must’ in (5) targets a body of norms.

-

(5)

We must help the poor.

All types of theories—contextualist, relativist, expressivist, invariantist—can accept that certain modal words, qua lexical items, are context-sensitive in the sense that the context of utterance determines what type of reading the modal receives.Footnote 3 What is at-issue is, given that the modal has an epistemic reading, whether a specific body of information supplied by the context of utterance figures in calculating the semantic content, or compositional semantic value, of the sentence-in-context, where what information is supplied may vary across contexts within a world.Footnote 4 Non-contextualist accounts deny this. Debates about contextualism arise for words whose lexical semantics fixes an epistemic reading (e.g., ‘probably’, ‘likely’).

Second, the focus in this paper is on (what I call) expressive uses of epistemic modals. Adapting terminology from Lyons (1977, 1995), say that an unembedded modal is used expressively if the speaker is presented as endorsing the considerations with respect to which the modal is interpreted; and say that the modal is used non-expressively if the speaker isn’t presented in this way.Footnote 5 The non-expressive deontic use in (6) simply reports what Ed’s parents’ rules require. Similarly the non-expressive epistemic use in (7), adapted from Kratzer (2012), describes what is possible according to the information provided in the filing cabinet.

-

(6)

Bert: Ed has to be home by 10. Aren’t his parents stupid? I’d stay out if I were him.

-

a.

≈According to Ed’s parents’ rules, Ed has to be home by 10.

-

a.

-

(7)

[Context: We’re standing before a locked filing cabinet. None of us has had access to the information in it, but we know it contains the police’s complete evidence about the murder of Klotho Fischer and narrows down the set of suspects. We’re betting on who might have killed Fischer according to the information in the filing cabinet. The butler, who we all know is innocent, says:]

I might have done it. (Kratzer 2012: 98–99)

The descriptive beliefs expressed by (6)–(7) can be reported in attitude ascriptions:

-

(8)

Bert thinks Ed has to be home by 10.

-

(9)

The butler thinks he might have done it.

The verifying norms/information in (6)–(9) needn’t be accepted by Bert/the butler.

All types of theories can accept that such descriptive uses—uses readily paraphrasable with an explicit ‘according to’-type phrase—are context-sensitive in the same way as paradigm context-sensitive expressions. The distinctive claim of contextualism is that the expressive uses of epistemic modals are context-sensitive in the same way as (e.g.) (4) and (7). The expressive uses in (2) intuitively convey epistemic attitudes about the embedded proposition, which reflects the subject matter of the discourse. States of mind expressed in expressive uses can be reported in attitude ascriptions, as in (3) or (10b).

(10) | a. | A: It must be raining outside. Look at all those people with wet umbrellas. |

b. | A thinks it must be raining outside. |

Attitude ascriptions such as (3)/(10b)—call them expressive epistemic attitude ascriptions—present the attitude subject as accepting the information with respect to which the modal is interpreted. It is expressive uses which have been argued to be problematic for contextualism. (Hereafter, unless otherwise noted, assume all examples involve expressive uses.)

2 Embedding problems

2.1 First-order states of mind

Insofar as contextualism treats the contextually relevant information as figuring in the content of an epistemic modal clause, contextualism seems to treat (11) as ascribing to Alice the belief that the contextually relevant information is compatible with the proposition that the butler is the killer.

-

(11)

Alice thinks the butler might be the killer.

The worry is that this incorrectly treats epistemic attitude ascriptions as ascribing higher-order attitudes about a body of information.Footnote 6 Here is Seth Yalcin (2007: 997):

Suppose my guard dog Fido hears a noise downstairs and goes to check it out... I say:

[(12)] Fido thinks there might be an intruder downstairs.

...Does [this] mean, as a [contextualist] semantics requires, that Fido believes that it is compatible with what Fido believes that there is an intruder downstairs? That is not plausible. Surely the truth of [(12)] does not turn on recherché facts about canine self-awareness. Surely [(12)] may be true even if Fido is incapable of such second-order beliefs.

Likewise, (13) doesn’t ascribe to Alice the sorts of attitudes ascribed in (13a)–(13b):

(13) | Alice fears that the butler might be the killer. | |

a. | ≉Alice fears that it’s compatible with her/our/whomever’s evidence that the butler is the killer. | |

b. | ≉Alice fears that she doesn’t know who the killer is. | |

Alice’s fear is about who the killer is, not herself or the strength of her evidence.

Epistemic attitude ascriptions seem to characterize the subject’s first-order state of mind. (11) characterizes Alice as accepting information which is compatible with the butler’s being the killer. The challenge is to capture this within a contextualist semantics.

2.2 Obligatory shifting

Epistemic modals appear to behave differently from paradigm context-sensitive expressions (“PCS-expressions”) under attitude verbs. Even when embedded under ‘thinks’, ‘I’ must be interpreted with respect to the context of utterance, or “global” context. (I use ‘global context’, ‘context of utterance’, and ‘discourse context’ interchangeably.)

(14) | B: A thinks I am hungry. | (global reading obligatory) | |

a. | ≈A thinks B is hungry. | ||

b. | ≉A thinks A is hungry. | ||

Not all context-sensitive expressions must be interpreted with respect to the context of utterance in this way. ‘Local’, for example, can be interpreted with respect to the “local” (subordinate, derived) context characterizing the subject’s attitude state, as in (15b). If Bob is in Boston, Pete is in Ann Arbor, and Pete thinks that Al is at Ashley’s, a bar in Ann Arbor, Bob can report Pete’s belief by uttering (15). Yet ‘local’ can still also be interpreted with respect to the global context, as in (15a). Bob can utter (15) to report Pete’s belief that Al is at Ashley’s even if Bob is in Ann Arbor and Pete is in Boston.

(15) | Bob: Pete thinks Al is at a local bar. | (global reading possible) | |

a. | ≈Pete thinks Al is at a bar local to Bob | ||

b. | ≈Pete thinks Al is at a bar local to Pete | ||

The generalization is that PCS-expressions are at least optionally interpreted with respect to the context of utterance. By contrast, there seems to be no reading of (11) on which Chip is ascribing to Alice the belief that it’s compatible with Chip’s evidence that the butler is the killer.

(11) | Chip: | Alice thinks the butler might be the killer. | (local reading obligatory) |

The worry is that, unlike PCS-expressions, epistemic modals are obligatorily linked to the attitude subject.

This objection is sometimes put by saying that epistemic modals needn’t be interpreted with respect to the information relevant in the context of utterance.Footnote 7 This is too weak. The relevant contrast is that, unlike PCS-expressions, epistemic modals can’t be interpreted with respect to the global context when embedded in attitude ascriptions. So, it’s insufficient for contextualists to reply by pointing to cases, like (15), where PCS-expressions are linked to the attitude subject, or to reply by noting that in contexts where we are reporting someone’s belief, it can be that person’s information that is “relevant.”Footnote 8 The worry is that there is no reading of (11) that characterizes Alice’s beliefs in terms of the information accepted in the discourse context.

2.3 Epistemic contradictions

The third objection concerns the behavior of epistemic modals in suppositional contexts. Consider the following Moore-paradoxical sentence:

(16) | # | The butler is the killer, but I don’t think that he is. | |

Though it would be anomalous to utter (16), the incoherence vanishes when (16) is embedded in suppositional contexts:

(17) | okSuppose the butler is the killer but I (/you) don’t think he is. | ||

(18) | okIf the butler is the killer but I don’t think he is, I’m screwed. | ||

That (16) can be coherently entertained shows that it isn’t a semantic contradiction. The anomalousness of (16) is due to a feature of asserting (16). Roughly, the second conjunct denies what asserting the first conjunct expresses.

Seth Yalcin (2007, 2011) notices something striking about analogous examples like (19) with ‘might’: Unlike (16), the “epistemic contradiction” (Yalcin’s phrase) in (19) cannot even be coherently entertained, as reflected in (20)–(21).

(19) | #The butler is the killer, but he might not be. |

(20) | #Suppose that [the butler is the killer but he might not be]. |

(21) | #If the butler is the killer but he might not be, I’m screwed. |

Yet this can’t be because (19) is an ordinary contradiction, since ‘Might ϕ’ doesn’t entail ‘ϕ’.

Embedded epistemic contradictions pose a challenge for contextualist semantics in general. For any (possibly single-membered) group G, it should be coherent to entertain the possibility that ϕ and G doesn’t think/know that ϕ. But it isn’t coherent to entertain the possibility that ϕ and it might be that \(\lnot \phi.\) So, ‘ϕ and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ isn’t equivalent to ‘ϕ and it’s compatible with G’s information that \(\lnot \phi\)’, for any G.

Some have responded that the anomalousness of epistemic contradictions persists in suppositional contexts because epistemic modals are always anomalous in suppositional contexts (cf. Schnieder 2010; Crabill 2013).Footnote 9 I have two worries with this response. First, perhaps contrary to initial appearances, epistemic modals can felicitously occur in suppositional contexts:

(22) | If the butler might be the killer, we should watch our backs around him, just in case. | ||

(23) | If a tiger might be in the bushes, don’t wait to find out. | ||

(24) | Imagine you’re stuck at your cubicle and it must be raining out—you see a bunch of people come in with wet umbrellas. | ||

Intuitively, the advice in (22) is conditional on one’s taking it to be possible that the butler is the killer. What (24) asks you to imagine is that you have indirect evidence which implies that it’s raining.

Second, observe that “epistemic contradiction”-style phenomena arise with other expressions which have figured in recent contextualism/relativism debates:

(25) | a. | # | The brownies are tasty but we all hate them. |

b. | # | Suppose the brownies are tasty but we all hate them. | |

(26) | [Context: Ken is \(5'6''\) tall.] | ||

a. | # | Ken is tall but the standards for tallness are super high. | |

b. | # | Suppose Ken is tall but the standards for tallness are super high. | |

However, there are no putative analogous embedding restrictions on (e.g.) ‘tasty’ or ‘tall’. Contextualists should be wary of responses which turn on features specific to epistemic modals. Such explanations are unlikely to generalize.

3 Embedding solutions

I will argue that we can derive the embedding phenomena from Sect. 2 from a particular contextualist interpretation of a standard semantics for modals, independently attested mechanisms of local interpretation, and general features of discourse contexts. We will also see that the literature has been too quick to grant certain of the data. The distinctiveness of epistemic modals’ embedding behavior shouldn’t be overstated.Footnote 10

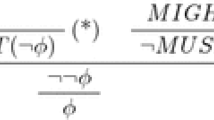

3.1 Formal semantics

I start by briefly characterizing the contextualist formal semantics I will be assuming. Following common practice I treat modal verbs as semantically associated with a parameter or variable determining a set of premises (propositions).Footnote 11 Roughly put, ‘Must ϕ’ says that ϕ follows from these premises, and ‘May ϕ’ says that ϕ is compatible with these premises. Since modals can occur in intensional contexts, premise sets are indexed to the world of evaluation. What context supplies for interpretation is a premise frame (written ‘P’), or function from worlds w to premise sets (written ‘P(w)’). Epistemic readings call for a premise frame that encodes a body of information (evidence, knowledge, etc.).Footnote 12

It’s common in linguistic semantics to treat various paradigm context-sensitive expressions on the model of variables, which receive their values from a contextually determined assignment function \(g_c\) (e.g., Heim and Kratzer 1998). To fix ideas I assume that premise frame parameters are also syntactically realized as variables (von Fintel 1994; Frank 1996; Schaffer 2011). Semantically associating epistemic modals with a contextual variable places constraints on their felicitous use and interpretation. To illustrate, compare a treatment of pronouns as variables. A free pronoun, say ‘\(\hbox {it}_4\)’, denotes the individual assigned to it by the assignment:

-

(27)

\(\llbracket {\text{it}_4} \rrbracket^{c,g_{c},w}\) = \(g_c(4)\)

-

(28)

\(\llbracket {\text{it}_4 \text{ is } \text{ a } \text{book}} \rrbracket^{c,g_{c},w} = 1\) iff \(g_c(4)\) is a book in w

Using ‘\(\hbox {It}_4\) is a book’ to describe, say, Middlemarch assumes that the context determines an assignment \(g_c\) that maps the (typed) index 4 to Middlemarch, and asserts that \(g_c(4)\) is a book. Such an assignment represents that Middlemarch is the most salient object in the context. Likewise, a free premise frame variable, say \({\mathbf{P}}_{\mathbf{7}}\), denotes the premise frame determined by the assignment:

-

(29)

\(\llbracket {\mathbf{P}}_{\mathbf{7}} \rrbracket^{c,g_c,w}\) = \(g_c(7)(w)\)

-

(30)

\(\llbracket \text{Sal} \text{ might } {\mathbf{P}}_{\mathbf{7}} \text{ have } \text{ killed } \text{Fischer} \rrbracket^{c,g_c,w}\) = 1 iff \(\bigcap (g_c(7)(w) \cup \{k\}) \ne \emptyset\)

Using ‘Sal might \({\mathbf{P}}_{\mathbf{7}}\) have killed Fischer’ in the context in (7) assumes that the context determines an assignment \(g_c\) that maps the (typed) index 7 to a premise frame P encoding the information in the filing cabinet, and asserts that \(g_c(7)(w)\) is compatible with the proposition k that Sal killed Fischer. Such an assignment represents that P encodes the salient information provided in the filing cabinet.

Expressive uses of epistemic modals, I suggest, call for a premise frame variable that represents information endorsed in the context. For expository purposes I will write ‘P e ’ for the variable invoked in expressive uses of epistemic modals, with the index e simply to indicate the intended assignment and interpretation of the variable. In the unembedded case P e typically corresponds to the discourse common ground—the set of propositions taken for granted for purposes of conversation (Stalnaker 1974, 1978; complications will follow shortly). This reflects the paradigmatic role of epistemic modals in communal inquiry. There are various ways of formalizing these points. One option is to introduce the endorsement condition as a feature or presupposition on premise frame variables:

-

(31)

\(\llbracket {\mathbf {P_{e8}}} \rrbracket^{c,g_{c},w}\) = \(g_c(8)(w)\) if \(g_c(8)\) is a body of information endorsed in c, undefined otherwise

Generally speaking, an expressive use of epistemic ‘Might (/Must) \(\phi\)’ presupposes a value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\), \(P_{c}\), and is true at w iff \(\phi\) is compatible with (/follows from) \(P_{c}(w)\).Footnote 13 The expressive use presupposes that the verifying information \(P_{c}\) is endorsed in the context.

With the above formal semantics at hand, let’s return to the objections from Sect. 2.

3.2 First-order states of mind

The first objection was that contextualism incorrectly treats attitude ascriptions like (11) as ascribing higher-order attitudes about a body of information.

(11) | Alice thinks the butler might be the killer. | ||

First, note that on the semantics from Sect. 3.1 there is no reference to the discourse context or “the relevant information,” considered de dicto, in the content of the attitude ascribed. Common characterizations of contextualism notwithstanding,Footnote 14 on the present semantics epistemic modal sentences aren’t fundamentally about an individual or group; they make logical claims given an epistemic premise set. (11) ascribes to Alice the belief that a certain set of propositions is compatible with the proposition b that the butler is the killer. But how does treating (11) as ascribing to Alice this sort of logical belief capture the intuition that (11) characterizes Alice’s first-order belief state?

It’s well-known that many embedding environments introduce local (derived, subordinate) contexts. In (32) the presupposition associated with ‘Ursula’ (‘it’, ‘the unicorn’) that a suitable discourse referent exists isn’t “globally satisfied,” i.e. implied by the discourse common ground; the presupposition is, however, satisfied in the expression’s local context, i.e. the context representing Fred’s beliefs (Stalnaker 1988, 2014; Heim 1992; Geurts 1998).

(32) | There are no unicorns, but Fred thinks there are. He thinks he has a pet unicorn named ‘Ursula’. He thinks Ursula (/it, /the unicorn) can fly. | ||

Call readings such as the felicitous reading of (32) local readings. I use this label descriptively for readings in which, intuitively speaking, a presupposition is interpreted as contributing to the local (truth-conditional) content.Footnote 15 Local interpretation (in this more-or-less pretheoretic sense) not only allows one to use ‘Ursula’ (‘it’, ‘the unicorn’) in (32) without presupposition failure. It also guides how the expression is interpreted.

I suggest that we capture the intuition that (11) characterizes Alice’s first-order state of mind in terms of the communicative upshot of locally interpreting the embedded epistemic modal. Expressive uses of epistemic modals presuppose a value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\); they presuppose a body of information endorsed in the context. With epistemic attitude ascriptions the relevant context is the local context of the attitude state; the locus of endorsement is the attitude subject. In locally satisfying the presuppositions of ‘might’ in (11), one assumes that Alice’s state of mind characterizes a value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\), \(P_A\), that makes the belief ascription true. Ascribing to Alice the belief that \(P_A\) is compatible with b via (11) communicates something about Alice’s information state because of how the presuppositions of the epistemic premise frame variable are assumed to be locally satisfied.

A natural move is to identify the locally supplied value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) with a premise frame representing the subject’s beliefs, which determines the attitude verb’s quantificational domain.Footnote 16 But this implementation isn’t forced upon us. Consider the following modification of (7):

-

(33)

[Context: You are standing in front of a locked filing cabinet. You don’t have access to its contents, but you know that it contains the complete evidence about Fischer’s murder and narrows down the set of suspects. You have partial amnesia, and although you remember that you had a grudge against Fischer, you can’t remember if you ended up taking matters into your own hands. I ask you whether it’s possible that you did it. You say:]

I don’t know. I don’t know whether I might have killed him.

Intuitively, ‘might’ is interpreted with respect to the information provided in the filing cabinet. But the use is “expressive” in the sense that you treat this information as authoritative and would accept it if you were explicitly presented with it. One way of capturing this is as follows. Which premise set is relevant for evaluating a modal sentence can depend on how things are, or on how things could be or could have been. That is why premise sets are world-indexed and what context supplies, reflecting the modal’s intended reading, is treated as a function from worlds to premise sets. The information endorsed by the subject, hence value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\), is represented by a premise frame—in (33), one which maps each world w to a set of propositions P(w) encoding (among other things) the information in the filing cabinet in w. Given your amnesia, what information is provided varies across your epistemic alternatives. Roughly, (33) says that for some u, v in your epistemic alternatives, P(u) is incompatible with your being the killer, and P(v) is compatible with your being the killer.

So, the contextualist can avoid the seemingly implausible claim that “an embedded epistemic claim is always about the current investigation of the actual context” (Yanovich 2014: 92). The relevant context with respect to which epistemic modals (and other context-sensitive expressions) are interpreted can be the local context characterizing an embedding environment. This doesn’t imply that the discourse context plays no role in interpreting embedded epistemic modals. Consider a third-person analogue of (33) in which Rudolf is the amnesiac, we’re investigating the murder, and our question is whether to rule out Rudolf on the basis of his testimony. In this context we might say:

(34) | Rudolf thinks he might have done it. | ||

How the value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) is determined in the local context, and whether it is identified in terms of the subject’s attitude state, can depend on what issues are relevant in the global discourse context.

3.3 Obligatory shifting

The treatment of epistemic attitude ascriptions in Sect. 3.2 reframes the worry from Sect. 2.2: Even if presuppositions associated with context-sensitive expressions can be locally satisfied, they don’t have to be. The contextualist semantics developed thus far doesn’t itself exclude interpreting embedded epistemic modals with respect to the information endorsed in the global context. However, I think this is a feature, not a bug. Differences among epistemic modals and various other expressions vis-à-vis preferences for local/global readings can be explained, at least in part, in terms of the sentences’ specific contents and general features of concrete discourses.

First consider an example from Jennifer Saul (1998: 366). We’re talking about people’s views on Bob Dylan’s singing abilities. I know that Glenda, one of his childhood friends, knows him only under the name ‘Robert Zimmerman’. Yet, since you know him only under the name ‘Bob Dylan’, I can felicitously use ‘Bob Dylan’ to characterize Glenda’s belief, as in (35), even though she “wouldn’t put it that way.”

(35) | Glenda thinks Bob Dylan has a beautiful voice. (Saul 1998: ex. 7) | ||

This is because (a) what matters for our purposes is Glenda’s belief about the individual with whom we associate ‘Bob Dylan’, (b) it doesn’t matter for our purposes what, if anything, Glenda associates with ‘Bob Dylan’, and (c) we have reason to express the content that Bob Dylan has a beautiful voice using ‘Bob Dylan’ because it’s a convenient way of talking about the individual we want to talk about.

This observation suggests the following analogous conditions for context to make available a global reading of an epistemic belief ascription:

-

(a) What matters for our purposes is the subject’s belief about the logical claim in question, as determined by the information endorsed in the discourse.

-

(b) It doesn’t matter for our purposes what the subject’s information is.

-

(c) Nevertheless, we have reason to express the content of the subject’s belief using an epistemic modal.

With epistemic modals, unlike (e.g.) names, it’s highly unusual for context to satisfy these conditions. Names provide a way for speakers to bring attention to entities in order to communicate something about them. Felicitously using a name thus typically requires that everyone in the conversation associates the same thing with the name. Felicitously using epistemic modals, by contrast, often doesn’t require having explicitly settled on a specific body of information. Indeed, a principal feature of epistemic modals often regarded as problematic for contextualism is their role in managing speakers’ assumptions about what possibilities to treat as live.Footnote 17 But if there isn’t an agreed-upon body of information salient in the discourse, uttering a non-subject-linked epistemic attitude ascription runs the risk of failing to clearly characterize the subject’s beliefs. Explicitly specifying this information—‘S thinks such-and-such information implies/is compatible with ϕ’—would make the intended interpretation more readily retrievable. So, using a bare epistemic modal instead would be dispreferred. Even so, I think we can construct contexts which satisfy conditions (a)–(c) and license global readings.

Suppose we’re stuck in the lab with no access to windows, phones, internet, etc., and we’re wondering what the weather is like outside. Earlier we saw Harry and Ingrid with what appeared to be wet rain jackets, and Harry seemed more glum than usual. We’re terrible at figuring out what the weather is like given this sort of indirect evidence, but we know Georgina is excellent at it. So we send Jerry to her office to ask what she thinks. We don’t know whether Georgina herself would accept our apparent evidence as reliable—she is a cautious character—but we accept it. When Jerry gets back, we ask him what Georgina thinks about what the weather must be like, given our evidence. Jerry says:

-

(36)

She thinks it must be raining. The sprinklers never come on on Fridays. Ingrid never wears a jacket unless it’s raining. And Harry hates the rain; it’s the only thing that could get him down after his team wins, which they did yesterday.

Jerry’s utterance seems felicitous. The (a)-condition is met since what we’re interested in is Georgina’s belief about whether our evidence about Harry and Ingrid licenses inferring that it’s raining. The (b)-condition is met since it doesn’t matter for our purposes whether Georgina accepts our testimony about this evidence. It’s explicit in the conversation that we accept it, and that Georgina tends to be more skeptical. And the (c)-condition is met since we treat Georgina’s belief about the logical properties of our evidence as relevant to what we should infer about the weather, and since our mutual acceptance of this evidence is already contextually salient. So, there is no potential confusion about the intended interpretation of ‘must’ or about what belief is being ascribed.

It’s a commonplace that conversational factors can affect what readings are available for sentences with lexically underspecified content. Although context typically leaves global readings of epistemic attitude ascriptions unavailable, exceptions may be possible in principled types of circumstances. We can provide a unified semantics for epistemic attitude ascriptions like (10b)/(11) and (36) along with a conversational explanation for their differences.

It’s worth pausing to reflect on the theoretical import of examples such as (36). I grant that global readings of epistemic attitude ascriptions are typically marked, and that even if global readings are possible, they require substantial contextual setup. One might wonder whether it would theoretically preferable to introduce non-contextualist semantic mechanisms that predict obligatory subject-linking with epistemic modals—e.g., an informational parameter in the index which is systematically shifted by attitude verbs (Sect. 4)—and then explain away examples like (36), perhaps like cases of coercion. I would like to make two points in reply.Footnote 18

First, note that a conversational explanation of the preference for local readings is compatible with this preference’s having become conventionalized. Even if it has, it remains open whether the conventionalized subject-linking is best captured within a contextualist or non-contextualist framework. For a contextualist, it might be captured as a substantive constraint in the lexical semantics—e.g., that the value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) be given by the assignment characterizing the immediate local context (cf. Truckenbrodt 2006 for a cross-linguistic precedent). Such a rule needn’t amount to a stipulation. Indeed our discussion provides a basis for the relative infrequency of global readings of epistemic attitude ascriptions—i.e., for why it would be relatively rare for speakers to characterize subjects’ beliefs about the logical properties of a body of globally endorsed information by using a bare epistemic modal, rather than by (e.g.) explicitly specifying the information. Given this infrequency, and general principles of cooperative conversation, we should expect speakers typically not to use bare epistemic modals to communicate such claims, and expect hearers typically not to assume global readings—highly artificial contexts such as in (36) notwithstanding (cf. Grosz 2014).Footnote 19 It might not be surprising if such interpretive patterns were eventually conventionalized in a lexical rule.

Moreover, there are positive reasons for preferring a contextualist implementation of the hypothesis that subject-linking with epistemic modals has become conventionalized. Tendencies for local versus global readings vary among context-sensitive expressions—both among paradigm context-sensitive expressions and expressions which have figured in recent contextualism/relativism/expressivism debates. For instance, we noted in Sect. 2.2 that perspectival expressions like ‘local’ naturally receive local readings. Likewise for the prestate presupposition of change-of-state verbs, as with ‘stop’ in (37):

-

(37)

Bert has never smoked, but Alice thinks he used to in college. She thinks he stopped smoking last week.

On the flip side, many positive form gradable adjectives exhibit distinctive discourse properties like those seen with epistemic modals, which has led some theorists to give them analogous non-contextualist semanticsFootnote 20; however, the conditions discussed above for the availability of global readings are more easily satisfied. Suppose that yesterday we were discussing with Alice how many hairs are on Harry’s head. It turns out she counted: 114. Now we’re at a party, and Bert, who wasn’t party to yesterday’s (all-too-lively) conversation, says he just saw “a bald man” across the room, but he isn’t sure if the man’s name is ‘Harry’ or ‘Gary’. Bert thinks that Alice, unlike us, is well acquainted with Harry. So he asks us, as a way of discovering the man’s identity, whether she thinks Harry is bald. Knowing that Bert accepts a high standard, and hence that having 114 hairs wouldn’t suffice for baldness by his lights, we say:

(38) | Alice thinks Harry isn’t bald. The man you saw must’ve been Gary. | ||

We can use Bert’s high standard, which we have accepted for purposes of conversation, to characterize Alice’s beliefs about the state of Harry’s head: (a) what matters for our purposes is Alice’s belief about Harry’s degree of baldness, and the relation between this degree and the standard for baldness (how bald one must be to count as bald) that is accepted in the discourse; (b) it doesn’t matter for our purposes what standard for baldness Alice accepts; (c) we have reason to describe Alice’s belief using ‘bald’ for the same reason we usually have to use vague language—greater specificity is unnecessary for addressing Bert’s question concerning the man’s identity. So, there is no risk of confusion about the intended interpretation of ‘bald’ or about what belief is being ascribed. These observations support the conversational explanation in this section for the apparent constraint against non-subject-linked readings with epistemic modals.

It’s beyond the scope of this paper to provide a general account of variations among context-sensitive expressions in preferences for local/global readings.Footnote 21 My point here is simply that there is a spectrum along which context-sensitive expressions fall in the extent to which they exhibit phenomena often thought problematic for contextualism.Footnote 22 On one side is (e.g.) gender presuppositions of pronouns, which typically receive global readings, as reflected in (39) (Sudo 2012).

(39) | #\({\hbox {Alice}}_i\) thinks \({\hbox {Sue}}_j\) is a man. \({\hbox {She}}_i\) thinks \({\hbox {he}}_j\) is kind. | ||

On the other side is epistemic modals, which typically receive local readings. But many expressions fall in between. Even if subject-linking has become conventionalized with epistemic attitude ascriptions, a strategy like the one pursued in this section promises a more explanatory account than existing (contextualist and non-contextualist) accounts which stipulate subject-linking in the lexical or compositional semantics, and a more theoretically unified account than non-contextualist accounts which capture the various embedding data via distinct compositional semantic mechanisms.

3.4 Epistemic contradictions

I think the literature has been too quick to grant the data concerning embedded “epistemic contradictions”—sentences such as ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ embedded in suppositional environments. First, as may be expected, examples with non-expressive uses are coherent: the possibility entertained in (40) is one where the police’s evidence, which we don’t endorse, is compatible with Lara’s having killed Fischer even though she didn’t.

(40) | [Context: Same as in (7).] |

If Lara didn’t kill Fischer but she might have, there’s a chance she’ll get screwed by the police. |

The more dialectically relevant observation is that there are also felicitous examples with expressive uses (Sect. 1)—the sorts of uses characteristic of inquiry and planning, those not readily paraphrasable with an ‘according to’-type phrase. Intuitively, the possibility entertained in (41) is one in which one’s evidence leaves open the possibility that a tiger is in the bushes even though there is actually no tiger there.

-

(41)

If a tiger might be in the bushes but there isn’t one, you should still run away. One can never be too careful.

Retrospective examples are also possible:

-

(42)

If there wasn’t a tiger in the bushes but there might have been, you still should have run away. You need to be more careful.

In (43) the evidence for interpreting ‘might’ is even endorsed in the discourse (Sect. 3.2).

-

(43)

[Context: Same as in (33). You, the amnesiac, say:]

I’m not sure whether I might have killed him. But if I might have killed him and I didn’t, there’s a chance I’ll get screwed.

I will continue to use ‘epistemic contradiction’ for sentences such as ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’, but we can now see that the label is tendentious. Though such sentences frequently give rise to a “phenomenology of contradiction” (Dorr and Hawthorne 2013)—hence the label—there needn’t be anything contradictory (infelicitous, incoherent) about embedded “epistemic contradictions.” Further, examples like (41)–(43) cannot be dismissed by a semantic theory. Unlike global readings of epistemic attitude ascriptions, felicitous embedded epistemic contradictions are available even with little-to-no contextual setup. Such examples pose a problem for any theory that treats accepting ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ as semantically incoherent. This includes not only Yalcin’s semantics but also various relativist and dynamic semantics.Footnote 23

Merely pointing out felicitous examples like (41)–(43) doesn’t suffice for a response to Yalcin’s puzzle. As Dorr and Hawthorne (2013) note, felicitous embedded epistemic contradictions raise a puzzle, not only for contextualists. All types of theories grant that epistemic modals sometimes receive (what I’m calling) non-expressive, descriptive readings (see n. 5). Yet when a sentence has multiple readings, some but not all of which are vacuously true/false, our typical response is to focus on coherent possible interpretations rather than judge the sentence infelicitous,Footnote 24 as we often do with epistemic contradictions. We need to explain how the (in)felicity of embedded epistemic contradictions depends on context, and why, if (say) a contextualist semantics is correct, embedded epistemic contradictions are often anomalous in “out-of-the-blue” contexts and often worse than examples where an information state is explicitly specified.

Start with an unembedded epistemic contradiction:

-

(19)

#The butler is the killer, but he might not be.

Updating with the first conjunct restricts the context set to b-worlds in which the butler is the killer. However, the second conjunct assumes a value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) that is compatible with \(\lnot b\). Given the conceptual connection between \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\), which represents a body of endorsed information, and the discourse common ground, these constraints are incompatible.

Analogous points hold with epistemic contradictions embedded in suppositional environments. It’s well known that conditional antecedents and suppositional verbs, like attitude verbs, establish subordinate information states.Footnote 25 In (44) ‘suppose’ sets up a local context which includes the information that there is a thief. This licenses using the pronoun even though its existence presupposition isn’t satisfied by the discourse common ground.

(44) Suppose a thief breaks in. He would take the silver. | (cf. Roberts 1989: ex. 13) |

Linking the epistemic modal to the local suppositional information state predicts the incoherence of embedded epistemic contradictions, as in (20):

-

(20)

#Suppose that [the butler is the killer but he might not be].

The truth-conditional content of the non-modalized conjunct requires that this local context imply b. However, the modalized conjunct presupposes a value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) that is compatible with \(\lnot b\). Given the conceptual connection between the locally supplied value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) and the suppositional information state, these demands are inconsistent.

This account avoids problems with saying that epistemic contradictions are anomalous because ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ is a literal contradiction. ‘\(\phi\)’ and ‘might \(\lnot \phi\)’ can both be true at a point of evaluation. The incoherence in anomalous uses of epistemic contradictions derives from the presuppositional effects of the epistemic modal on the context in which the non-modal conjunct is proposed for acceptance: Updating with the truth-conditional content of ‘\(\phi\)’ requires restricting the context to \(\phi\)-worlds, but accommodating a suitable value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) associated with ‘might \(\lnot \phi\)’ requires that the context include some \(\lnot \phi\)-worlds. Just as (19) places incompatible constraints on the global context, (20) places incompatible constraints on the local suppositional context. For embedded examples, given the conceptual connection between the suppositional state and a locally accommodated value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\), it is natural in an “out-of-the-blue” context to resolve \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) to the body of information characterizing the local suppositional context. This, along with the descriptive fact that epistemic modal verbs are typically used expressively,Footnote 26 helps explain the general infelicity of embedded epistemic contradictions in discourse-initial contexts. However, we have seen that context can sometimes call for alternative ways of determining the value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) in expressive uses, and alternative epistemic premise frame variables in non-expressive uses. This correctly predicts the felicity of embedded epistemic contradictions in such contexts, as we saw with (40)–(43).

First, the non-expressive use in (40) calls for a premise frame variable representing the information in the filing cabinet. More interesting are the expressive uses, interpreted with respect to the variable \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) representing a body of endorsed information. The deliberative/retrospective contexts in (41)–(42) makes evident why one is being asked to entertain a state of mind that doesn’t fully track the facts: in (41) we are planning for the possibility that our information is compatible with a tiger being in the bushes, though there is in fact no tiger there; in (42) we are evaluating courses of action taken in such a possibility. The specific contents of the suppositions suggest natural ways of readily accommodating a suitable body of information—perhaps we hear rustling, catch a glimpse of black stripes, etc. Third, (43) shows that coherent embedded epistemic contradictions are possible with a globally supplied value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\). You endorse the information provided in the filing cabinet, though you don’t know what it consists of (Sect. 3.2). The possibility being entertained is one where this information is compatible with your having killed Fischer even though you didn’t actually kill him. Embedded epistemic contradictions will be anomalous to the extent that there isn’t a relevant, readily retrievable premise frame that yields a coherent interpretation in one of these types of ways.

Dorr and Hawthorne (2013) also aim to provide a contextualist-friendly explanation of the variety of data involving epistemic contradictions. Dorr and Hawthorne (D&H) explain the bias toward anomalous readings of embedded epistemic contradictions—on my reconstruction of their discussion—in terms of four general claims about conversation and interpretation:

-

(i)

Hereditary Constraint: Most uses of epistemic modals are about the knowledge of the speaker or a relevant group. However, epistemic modals sometimes receive “constrained” readings, which mix further contextual information—e.g., in conjunctions (disjunctions, conditional consequents) where the modal inherits a constraint from the non-modalized conjunct (disjunct, conditional antecedent): sentences of the form ‘\(\phi\) and might/must \(\psi\)’ are often given a “hereditarily constrained” interpretation truth-conditionally equivalent to ‘\(\phi\) and in some/all epistemically possible worlds in which \(\phi\), \(\psi\)’ (with epistemic possibility understood narrowly in terms of a relevant subject’s knowledge).Footnote 27

-

(ii)

Transparency: We typically assume that people know what they know.

-

(iii)

Ignorance Implicatures: Conditionals with conjunctive antecedents typically implicate that one doesn’t know either conjunct.

-

(iv)

Preference for Explicitness: In certain types of circumstances, sentences with implicit contextually supplied arguments are generally dispreferred to sentences which linguistically specify those arguments.

Very roughly: Given Ignorance Implicatures, uttering ‘If \(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)...’ typically implicates that the speaker doesn’t know whether ‘might \(\lnot \phi\)’ is true. Because of Transparency, we thus avoid interpreting ‘might’ simply in terms of the speaker’s knowledge. Absent a salient alternative interpretation, we may then focus on a hereditarily constrained interpretation, as per Hereditary Constraint. But ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ is inconsistent on such an interpretation. Further, we won’t then seek some coherent narrowly epistemic interpretation—on which ‘might \(\lnot \phi\)’ is interpreted with respect to some other subject S’s knowledge (\(\approx\)‘S doesn’t know that \(\phi\)’)—since, from Preference for Explicitness, using ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ would be a bad way of expressing any such interpretation. Hence the general anomalousness of ‘If/Suppose \(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)...’.

There are important differences between D&H’s contextualist account and the account in this paper—both in the semantics, concerning the specific truth-conditions, and in the pragmatics, concerning the interpretive mechanisms and conversational factors responsible for generating the posited interpretations. Briefly canvassing some of these differences, even if only briefly, will help clarify certain distinctive features of the contextualist account developed here.

First, concerning D&H’s diagnosis of anomalous epistemic contradictions: D&H may be correct that epistemic modals in conjunctions often receive something like a “hereditarily constrained” interpretation. Yet no account is given of the mechanisms which generate the “hereditary” constraint, or of why the constrained interpretations are typically so prominent (n. 27). The account in this paper avoids appealing to hereditarily constrained interpretations, as D&H understand them. Expressive uses of epistemic modals are treated as presupposing a body of information endorsed in the context. Anomalous readings of ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ are diagnosed, not in terms of truth-conditional inconsistency, but in terms of incoherence in accepting \(\phi\) and presupposing information compatible with \(\lnot \phi\).

Second, concerning D&H’s account of the general bias toward anomalous readings of epistemic contradictions: Their central claim here is Preference for Explicitness; this claim, D&H argue, explains why speakers dont fall back on coherent interpretations of ‘might \(\phi\)’ about a subjects/group’s knowledge. As D&H note, the preference for linguistically specifying arguments cannot be fully general; we felicitously leave arguments implicit all the time (indeed, in many cases, even when no specific contextual resolution is especially salient; cf. Silk 2016a: Sect. 4.4 and references therein). Crucial, then, is to specify the circumstances in which the posited interpretive preference holds. D&H suggest the importance of contrast. For instance, in (45) it seems dispreferred to indicate the contrast in locations while leaving one location implicit.

(45) | a. | It’s not raining over there but it’s raining here. | |

b. | It’s not raining over there but it’s raining. | ||

(Dorr and Hawthorne 2013: ex. 40) | |||

Likewise, D&H suggest, ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ introduces a contrast between reality and a subject’s knowledge of it; hence the infelicity of (46b) as a way of communicating the content of (46a), even in discourses which make Sally’s knowledge especially salient.

(46) | a. | Fred isn’t on that bus and Sally doesn’t know it. | |

b. | Fred isn’t on that bus and he might be. | ||

(Dorr and Hawthorne 2013: ex. 49) | |||

Two concerns: First, more needs to be said about the relevant notion of contrast. The examples in (47) intuitively introduce contrasts—in comparison classes, locations, and domain restrictions, respectively; yet they are felicitous despite leaving the arguments implicit.

(47) | a. This mouse is big [for a mouse], but this rhino isn’t big [for a rhino]. | |

b. The keys are there [\(l_1\)], not there [\(l_2\)]. | ||

c. Every sailor [on ship a] waived to every sailor [on ship b]. | ||

(cf. Stanley 2005: ch. 3) | ||

Felicitous examples where only one argument is pronounced are also possible (contrast (45)):

(48) | a. | This mouse is big for a mouse, but this rhino isn’t big. |

b. | The keys are there on the table, not there. | |

c. | Every sailor on that ship waived to every sailor. |

We need an explanation for why the alleged “contrast...between reality and Sally’s knowledge of it” (2013: 36) in (46) triggers the Preference for Explicitness, but the contrasts in (47)–(48) don’t.

Second, even if such an explanation were provided, I am skeptical that any appeal to contrast will capture “epistemic contradiction”-style phenomena with other types of expressions. Recall (25)–(26) with ‘tasty’ and ‘tall’ from Sect. 2.3. D&H might say the “tastes/standards contradictions” in (25a)–(26a) introduce contrasts between our tastes/standards and the tastes/standards of another relevant subject. But saying this would fail to explain the contrast between (25b)–(26b), which are infelicitous, and (49)–(50), which presumably also introduce contrasts, namely in evaluative attitudes, and yet are felicitous.

(49) | Suppose the Botticellis are beautiful but we don’t like them. (Then we should take an art appreciation class.) |

(50) | Suppose infanticide is wrong but we’re all for it. |

I won’t attempt a diagnosis of these broader examples here (see Silk 2016a: Sects. 5.3.2, 7.5). Suffice it to say that an explanation in terms of contrast, and an alleged Preference for Explicitness, is unlikely to do the trick.

Finally, the contextualist account in this paper provides a different way of understanding the puzzle posed by the broader epistemic contradictions data. Expressive uses of epistemic modals aren’t treated as claims about a relevant individual’s or group’s information (Sects. 3.1–3.2). Given that epistemic modals are typically used expressively (n. 26), it’s no surprise that hearers tend not to “rescue” epistemic contradictions by accommodating some third-party’s information.Footnote 28 What is needed is for context to provide a relevant way of determining the value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\) other than in terms of the common ground or suppositional information state, as in (41)–(43). Absent such an alternative (e.g., in many “out-of-the-blue” contexts), epistemic contradictions will be anomalous for the reasons explained above.

4 Conclusion

I have argued that we can derive various embedding phenomena with epistemic modals from a particular contextualist implementation of a standard framework for modals, general principles of interpretation, broader patterns of use, and typical features of discourse contexts. In closing I would like to briefly compare the contextualist treatment of embedding in this paper with certain relativist accounts. This may help clarify what is at-issue in debates about contextualism, and clarify some of the advantages/burdens of developing a contextualist account.Footnote 29

Contextualism, in the sense of Sect. 1, treats epistemic modals as semantically context-sensitive in the same general kind of way as paradigm context-sensitive expressions. What has been at-issue in this paper is a question of shifting: how to capture how the information intuitively relevant for interpreting an epistemic modal seems to shift from the discourse context in certain embedded linguistic environments. I offered empirical and methodological motivations for pursuing an approach which captures shifting phenomena with epistemic modals via the same interpretive mechanisms as shifting phenomena with various paradigm context-sensitive expressions. An alternative approach—call it relativism—is to posit distinct mechanisms for the two kinds of shifting phenomena: the information relevant for interpreting an epistemic modal is provided by an added parameter in the index—the sequence of parameters, like a world parameter, that can be shifted by linguistic operators, like modals and attitude verbs.Footnote 30 No particular body of information figures in the semantic content—unlike on a contextualist semantics—just as no particular world does:

-

(51)

\(\llbracket{\text{might }}\phi \rrbracket ^{c} = \left\{ \langle w, s\rangle :s \cap \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{c} \ne \emptyset \right\}\)

Locating the relevant information in the index predicts a systematic shift in the interpretation of epistemic modals under (e.g.) attitude verbs and suppositional operators: (52a) is true iff Alice’s beliefs are compatible with \(\phi\); the anomalousness of embedded epistemic contradictions derives from their placing incompatible truth-conditional constraints on the informational parameter shifted by the suppositional operator (n. 23).

(52) | a. | Alice thinks might \(\phi\) |

b. | \(\llbracket (52a)\rrbracket ^{c;\,w,s}\) = 1 iff \(\forall u \in Dox_{A, w}:Dox_{A, w} \cap \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{c} \ne \emptyset\) iff \(Dox_{A, w} \cap \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{c} \ne \emptyset\) |

However, first, attention to the broader spectrum of examples shows this generalization to be incorrect. Second, various distinctive phenomena exhibited by epistemic modals can be observed to varying extents with other types of context-sensitive expressions (n. 22). This undercuts some of the motivations for going relativist in the first place. The burden of proof shifts onto the relativist to motivate utilizing distinct semantic mechanisms for the array of cases. What initially seemed to be a cost of contextualism turns out to be a feature. The varieties of expressive and non-expressive uses, both with epistemic modals and other types of context-sensitive expressions, are treated as semantically context-sensitive in the same general kind of way. The goal is then to derive certain patterns/differences in their interpretation via the expressions’ conventional meanings—truth-conditional and presupposed—and general principles of interpretation and features of context. Even if certain embedding phenomena with epistemic modals are due partly to distinctive conventionalized constraints, such restrictions may have a conversational basis given a contextualist semantics.

There is much more to be said in comparing various contextualist and non-contextualist theories. The embedding phenomena considered here aren’t the only challenges raised by epistemic modals (n. 1). More thorough comparisons among context-sensitive expressions—including different types of paradigm context-sensitive expressions, additional categories of epistemic vocabulary, and other recalcitrant expressions that have figured in (non-)contextualism debates—is essential. Our broadly conversational account of embedding phenomena with epistemic modals has raised difficult empirical and theoretical questions about conventionalization, the varieties of context-sensitive language, and the roles of context in interpretation. I leave subsequent progressions of the dialectic to future research.

Notes

See Silk (2016a: ch. 7) for extensions to epistemic adjectives. See also Silk (2016a: Sects. 4.2.4–4.2.5) for discussion of epistemic modals in factive attitude contexts (cf. Weatherson 2008; Lasersohn 2009) and inferences (cf. Schroeder 2009; Braun 2013). See Klinedinst and Rothschild (2012), Yalcin (2012b), Moss (2015) for additional challenges from embedding.

Sometimes what body of information is relevant for interpreting an epistemic modal is explicitly specified, as in (i).

-

(i)

In view of Alice’s evidence, the butler might be the killer.

One might treat the modal words themselves as indexicals (like ‘here’) whose semantic contents depend on context. Alternatively one could treat the lexical items as having invariant semantic values and having argument places which may be filled by contextual parameters. Officially I remain neutral on these options. We will address details of the formal semantics in Sect. 3.1.

-

(i)

Following Yalcin (2014), there may be reasons to avoid using ‘(semantic) content’ as a label for a compositional semantic value in context. I use ‘content’ for this type of object simply for familiarity; my usage makes no assumptions about its potential broader theoretical role.

This distinction has been noted under various descriptions in a range of areas. See also, e.g., Hare (1952), von Wright (1963), Lasersohn (2005), Stephenson (2007), Narrog (2005), Verstraete (2007). For discussion in the literature on epistemic modals, see Yalcin (2007: 1012–1013), MacFarlane (2010: 13–16, 21–22; 2014: 155–156, 259–261, 272–277, 298), Egan (2011: 236), and Moss (2013: 7n.6; 2015: 41–43). For critical discussion, see Silk (2012, 2015b, 2016a) and Swanson (2016b). I use ‘endorsement’ as a general cover term for acceptance attitudes of various kinds, not simply deontic/evaluative; one can “endorse” (accept) evidence, information, norms, goals, etc. The present notion of an expressive use shouldn’t be confused with the category of linguistic expressives (e.g., interjections, expressive attributive adjectives, etc.); it is an open question, on my terminology, whether expressive uses are to be analyzed on the model of linguistic expressives.

See DeRose (2005, 2009), Cappelen and Hawthorne (2009), Dowell (2011), von Fintel and Gillies (2011), Finlay (2014: 236–245), Yanovich (2014). Remember that we are focusing only on expressive uses—uses in which the speaker/subject is presented as endorsing the information with respect to which the modal is interpreted. Some authors have claimed that epistemic modals disallow non-expressive uses in attitude contexts (Stephenson 2007; Weatherson 2008). That isn’t what is at-issue here. Hence pointing to examples, like (9), involving apparently non-expressive uses of epistemic modals in attitude ascriptions won’t suffice for responding to the present objection (e.g., Dowell 2011: 21–22).

For the descriptive claim that epistemic modals are disallowed in conditional antecedents, see, e.g., Leech (1971), Coates (1983), Drubig (2001). I will bracket any differences between examples with conditionals and examples with suppositional verbs (see Dorr and Hawthorne 2013 for discussion). See Verstraete (2007), Hacquard and Wellwood (2012), Anand and Hacquard (2013) for corpus studies on the distribution of epistemic modals in embedded contexts.

See Silk (2016a) for developments of a more general framework for implementing contextualism, which includes discussion of discourse dynamics with unembedded uses, as well as applications to epistemic adjectives and various other types of expressions which have figured in recent contextualism/relativism debates.

See esp. Kratzer (1977, 1981, 1991); also van Fraassen (1973), Lewis (1973), Veltman (1976), Lewis (1981), Goble (2013). Kratzer’s (1981, 1991) semantics uses two premise sets: a “modal base” premise set F(w) that describes some set of relevant background facts in w, and an “ordering source” premise set G(w) that represents the content of some ideal in w. This complication won’t be relevant here; I will treat modal sentences as evaluated with respect a single finite, consistent premise set. For simplicity I will sometimes suppress the world-indexing on premise sets; talk about a proposition p “following from (/being compatible with) P” can be understood as short for saying that p follows from (/is compatible with) P(w), for any relevant world w. (For a possible-worlds proposition p and set of propositions S, p follows from S (S implies p) iff \(\bigcap S \subseteq p\), and p is compatible with S iff \(\bigcap \left( S \cup \left\{ p\right\} \right) \ne \emptyset\).) I will use boldfaced type for parameters/variables, and italics for their values in context. I treat ‘ϕ’, ‘\(\psi\)’, etc. as schematic letters to be replaced with declarative sentences. For convenience I sometimes refer to the possible worlds proposition expressed by ‘ϕ’ by dropping the single quotes—e.g., writing ‘\(s \cap \phi\)’ as short for ‘\(s \cap \llbracket \hbox {`}\phi \hbox {'} \rrbracket^{c}\)’, where \(\llbracket \hbox {`}\phi \hbox {'} \rrbracket^{c} = \{w:\llbracket \hbox {`}\phi \hbox {'} \rrbracket^{c,w} = 1\}.\)

Differences in which epistemic relation is relevant won’t matter in what follows. To reiterate, I am not claiming that the general Kratzer-inspired framework for modals calls for contextualism about epistemic modals (Sect. 1). All types of theories can accept that the modal verbs are context-sensitive in the sense that the context of utterance determines what type of reading the modal receives. (For instance, a relativist or expressivist might treat what context supplies for interpreting a modal as a function from an evaluation world and judge to premise sets; what would be special about epistemic readings is that the contextually supplied function non-trivially depends on the value of the judge (cf., e.g., Stephenson 2007).

The subscripts are included simply for expository purposes to indicate the intended assignment and interpretation of the variable. My occasional talk about context supplying values for variables can be understood as short for talk about contextually determined assignment functions. For additional formal semantic details see Silk (2016a: esp. Sects. 3.3.5–3.3.6, 3.5.1, 5.6).

Whether this intuitive characterization provides a proper theoretical characterization of the phenomena is another matter (see also, e.g., Stalnaker 1974; Heim 1990; Schlenker 2009, 2010). What is important for our purposes is simply that concrete states of mind are like concrete discourses in being representable by abstract objects which supply semantic values for variables and other context-sensitive expressions.

The move would be to treat the value for \({\mathbf {P}} _{\mathbf {e}}\), P, as being such that \(\bigcap P(w) = Dox_{x, w}\), where \(Dox_{x, w}\) is the set of worlds compatible with x’s beliefs in w. Compare the relativist/expressivist accounts in Yalcin (2007), Hacquard (2010), MacFarlane (2011, 2014), Rothschild (2012), Silk (2013), Swanson (2016a); see also Stalnaker (2014: chs. 6–7) for critical discussion.

Thanks to Daniel Rothschild for discussion.

See Grosz (2014), drawing on Lewis (1969), for a game-theoretic derivation of a general conventionalized principle Utilize Cues!, which enjoins speakers to speakers to add explicit elements to make a marked (infrequent) use of an ambiguous utterance more salient, unless the intended interpretation is independently salient in the discourse context. It would be interesting to compare the conversational treatment of embedding phenomena in this section with discourse-based accounts of logophoricity (Kuno 1987; Pollard and Sag 1992). See note 9 for corpus studies on embedded epistemic modals.

E.g., Veltman (1996), Stephenson (2007), Hacquard (2010), MacFarlane (2011), Willer (2013). On Yalcin’s domain semantics, ‘\(\phi\) and might \(\lnot \phi\)’ is semantically incoherent in the following sense: when embedded, it places incompatible constraints on an information state parameter in the index; when unembedded, it places incompatible constraints on the context set. See Dorr and Hawthorne (2013: Sect. 3) for critical discussion of alternative ways of explaining the epistemic contradictions data within a broadly relativist framework.

Though not always. It would be instructive to compare the account in this section of (in)felicity patterns involving embedded epistemic contradictions in terms of preferences for local readings of epistemic modals, with (e.g.) discussions of (in)felicity patterns involving embedded gendered pronouns in terms of preferences for global readings of gender presuppositions (e.g. Sudo 2012: 30–34).

It’s in terms of the notion of constrained readings that D&H understand examples like (33): the information relevant for interpreting ‘might’ would be treated as combining the speaker’s knowledge (the narrowly epistemic considerations) with the information in the filing cabinet (the non-epistemic considerations, on their understanding). In the case of hereditarily constrained interpretation, D&H reject an implementation in terms of modal subordination, which treats the embedded epistemic modal’s quantificational domain in ‘\(\phi\) and might/must \(\psi\)’ as directly restricted to \(\phi\)-worlds (2013: 883–886), instead favoring an approach which treats the embedded modal claims as equivalent to ‘in some/all epistemically possible worlds that are accurate with regard to whether \(\phi\), \(\psi\)’.

Such a response is of course also available to non-contextualist theories. The present account predicts that making a third-party salient may improve judgments about epistemic-contradiction-style examples with expressions that more readily receive non-expressive readings. This prediction seems to be borne out, as reflected in (i) with ‘tasty’: the embedded ‘this cat food is tasty’ simply describes what tastes good to cats.

-

(i)

Suppose this cat food is tasty but we all hate it, and it’s the only food left on the planet. Then the cat will be happy, and we’ll probably starve to death.

-

(i)

Thanks to Daniel Rothschild and Paolo Santorio for discussion.

Relativism thus construed subsumes a variety of broadly relativist and expressivist accounts in the literature (see n. 16); see Silk (2016a: Appendix) for a more fine-grained taxonomy which draws on issues beyond semantic shifting (e.g., regarding the definition of truth-in-a-context, and the relation between compositional semantic value and asserted content). I ignore other potential parameters of the index, such as a time parameter. See Stalnaker (1970), Lewis (1980), Kaplan (1989) on the standard two-dimensional semantic framework; I bracket potential differences between a Lewisian index and a Kaplanian circumstance of evaluation.

References

Anand, P., & Hacquard, V. (2013). Epistemics and attitudes. Semantics and Pragmatics, 6, 1–59.

Barker, C. (2002). The dynamics of vagueness. Linguistics and Philosophy, 25, 1–36.

Bittner, M. (2011). Time and modality without tenses or modals. In M. Rathert & R. Musan (Eds.), Tense across languages (pp. 147–188). Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Björnsson, G., & Finlay, S. (2010). Metaethical contextualism defended. Ethics, 121, 7–36.

Braun, D. (2013). Contextualism about ‘might’ and says-that ascriptions. Philosophical Studies, 164, 485–511.

Brogaard, B. (2008). Moral contextualism and moral relativism. Philosophical Quarterly, 58, 385–409.

Cappelen, H., & Hawthorne, J. (2009). Relativism and monadic truth. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cappelen, H., & Lepore, E. (2005). Insensitive semantics: A defense of semantic minimalism and speech act pluralism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coates, J. (1983). The semantics of the modal auxiliaries. London: Croom Helm.

Crabill, J. D. (2013). Suppose Yalcin is wrong about epistemic modals. Philosophical Studies, 162, 625–635.

DeRose, K. (2005). The ordinary language basis for contextualism and the new invariantism. Philosophical Quarterly, 55, 172–198.

DeRose, K. (2009). The case for contextualism: Knowledge, skepticism, and context (Vol. 1). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dorr, C., & Hawthorne, J. (2013). Embedding epistemic modals. Mind, 122, 867–913.

Dowell, J. (2011). A flexible contextualist account of epistemic modals. Philosophers’ Imprint, 11, 1–25.

Dowell, J. (2012). Contextualist solutions to three puzzles about practical conditionals. In R. Shafer-Landau (Ed.), Oxford studies in metaethics (Vol. 7, pp. 271–303). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Drubig, B. (2001). On the syntactic form of epistemic modality. Tüebingen: University of Tüebingen.

Egan, A. (2011). Relativism about epistemic modals. In S. D. Hales (Ed.), A companion to relativism (pp. 219–241). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Egan, A., & Weatherson, B. (Eds.). (2011). Epistemic modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Finlay, S. (2009). Oughts and ends. Philosophical Studies, 143, 315–340.

Finlay, S. (2014). Confusion of tongues: A theory of normative language. New York: Oxford University Press.

Foley, W., & Van Valin, R. (1984). Functional syntax and universal grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frank, A. (1996). Context dependence in modal constructions. Ph.D. thesis, University of Stuttgart.

Geurts, B. (1998). Presuppositions and anaphors in attitude contexts. Linguistics and Philosophy, 21, 545–601.

Goble, L. (2013). Prima facie norms, normative conflicts, and dilemmas. In D. Gabbay, J. Horty, X. Parent, R. van der Mayden, & L. van der Torre (Eds.), Handbook of deontic logic and normative systems (pp. 241–352). Milton Keynes: College Publications.

Grosz, P. G. (2014). Optative markers as communicative cues. Natural Language Semantics, 22, 89–115.

Hacquard, V. (2010). On the event relativity of modal auxiliaries. Natural Language Semantics, 18, 79–114.

Hacquard, V., & Wellwood, A. (2012). Embedding epistemic modals in English: A corpus-based study. Semantics and Pragmatics, 5, 1–29.

Halliday, M. (1970). Functional diversity in language as seen from a consideration of modality and mood in English. Foundations of Language, 6, 322–361.

Hare, R. (1952). The language of morals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heim, I. (1990). On the projection problem for presuppositions. In S. Davies (Ed.), Pragmatics: A reader (pp. 397–405). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heim, I. (1992). Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics, 9, 183–221.

Heim, I., & Kratzer, A. (1998). Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kaplan, D. (1989). Demonstratives. In J. Almog, J. Perry, & H. Wettstein (Eds.), Themes from Kaplan (pp. 481–563). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Karttunen, L. (1974). Presupposition and linguistic context. Theoretical Linguistics, 1, 181–194.

Klinedinst, N., & Rothschild, D. (2012). Connectives without truth tables. Natural Language Semantics, 20, 137–175.

Kölbel, M. (2004). Indexical relativism versus genuine relativism. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 12, 297–313.

Kölbel, M. (2009). The evidence for relativism. Synthese, 166, 375–395.

Kratzer, A. (1977). What ‘must’ and ‘can’ must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy, 1, 337–355.

Kratzer, A. (1981). The notional category of modality. In H.-J. Eikmeyer & H. Rieser (Eds.), Words, worlds, and contexts: New approaches in word semantics (pp. 38–74). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (1991). Modality/Conditionals. In A. von Stechow & D. Wunderlich (Eds.), Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research (pp. 639–656). New York: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, A. (2012). Modals and conditionals: New and revised perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kuno, S. (1987). Functional syntax: Anaphora, discourse, and empathy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lasersohn, P. (2005). Context dependence, disagreement, and predicates of personal taste. Linguistics and Philosophy, 28, 643–686.

Lasersohn, P. (2009). Relative truth, speaker commitment, and control of implicit arguments. Synthese, 166, 359–374.

Leech, G. (1971). Meaning and the English verb. London: Longman.

Lewis, D. (1969). Convention: A philosophical study. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lewis, D. (1980). Index, context, and content. In S. Kanger & H. Ohman (Eds.), Philosophy and grammar (pp. 79–100). Holland: D. Reidel.

Lewis, D. (1981). Ordering semantics and premise semantics for counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 10, 217–234.

Lyons, J. (1977). Semantics (Vol. 2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lyons, J. (1995). Linguistic semantics: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacFarlane, J. (2010). Epistemic modals: Relativism vs. Cloudy Contextualism. MS, Chambers Philosophy Conference on Epistemic Modals, University of Nebraska.