Abstract

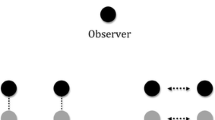

Ordinary human perceivers know that visual objects are perceivable from standpoints other than their own. The aim of this paper is to provide an explanation of how perceptual experience equips perceivers with this knowledge. I approach the task by discussing a variety of action-based theories of perception. Some of these theories maintain that standpoint transcendence is required for shape perception. I argue that this standpoint transcendence must take place in the phenomenal present and that it can be explained in terms of the experience of perceivers who jointly attend to an object. Joint perceivers experience objects as being perceived from standpoints other than their own. They operate in what I call “social space”, in which they single out objects by triangulating targets’ locations relative to their co-perceivers’ standpoints on these targets. It is then possible to explain the public character of the objects of individual experience by appeal to what I call “public space”. This is a spatial framework whose locations are presented as standpoints whence joint attention to the target would ensue, were they occupied by co-perceivers. If shape perception requires standpoint transcendence, then shape perceivers operate in public space and are thus capable of singling out targets by triangulating their locations from standpoints other than their own. If it doesn’t, then the introduction of a public spatial framework is an additional step whose introduction explains how perceivers come to experience objects as perceivable from standpoints other than their own.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

By “ordinary objects” I mean three-dimensionally extended visible space occupiers. Thus, your sofa is an ordinary object but a hallucination of your sofa is not.

Throughout this paper, I take perceptual objects to be “presented” rather than “represented” in experience. This is because of my commitment to a social form of epistemological disjunctivism (Seemann, 2019, pp. 67–72), the view that only joint experiences justify common knowledge claims about their objects; and because this form of disjunctivism is not obviously compatible with representationalism about experience.

A qualifier is in order: the object would be jointly perceived if currently unoccupied standpoints in a perceiver’s visual space were occupied by a co-perceiver and if a range of conditions are met. These include the absence of a visual barrier between the location of the co-perceiver and that of the target object, the object’s having the right size (it neither being too small nor too big to be visible in its entirety), the perceiver’s eyesight being sufficient, amongst others. Throughout this paper, I assume that these conditions are met.

I should highlight the somewhat speculative nature of this proposal. The notions of social space and of public space are hypotheses that are in need of further substantiation (though see Seemann (2019, chs. 10&11) for an extended discussion of social space). The viability of the present proposal depends on whether these hypotheses can be defended.

My use of the notion of “allocentric space” follows Grush (2001, p. 80): it is a space that “has another object, person, or perhaps just location as its origin.”

A reviewer wondered what the difference was between a centre of action and perception in egocentric space and a standpoint. An egocentre is an origin of perception and action—a point in space relative to which the location of various objects can be described indexically (“to my left”, “to my right”, etc.); see Section 8. It need not itself be specified relative to other objects in allocentric space. By contrast, a standpoint is a location that can be specified relative to other objects and happens to be occupied by a perceiver. This location therefore also serves as but is nevertheless not identical to an egocentre, You cannot occupy an egocentre other than your own, but you can change your standpoint on a target object by moving relative to it. This difference matters because it follows that standpoints but not egocentres can be transcended.

There are at least two ways in which standpoints can be transcended. First, you can transcend your standpoint on a perceptual object individually, by moving around it while keeping track of it or by encountering it for a second time while remembering that you have seen it from a different standpoint before. Secondly, and as I shall argue, you can also transcend your standpoint by jointly attending to an object with another perceiver.

This interpretation of the notion of joint attention is not neutral relative to all possible accounts. For instance, on a “lean” account of joint attention (Racine, 2011) there is no experiential dimension to joint attention. I follow Campbell (2002, 2011) in treating joint attention as an experiential phenomenon. Discussion is not possible here.

I sometimes say, in the interest of brevity, that in public space locations are standpoints whence joint attention to a target would ensue, were they occupied by co-perceivers. Given my definition of co-perceivers as perceivers with whom one jointly attends to an object, this description is, strictly speaking, circular. What I mean by it is this: locations in public space are standpoints whence, if they are occupied by other perceivers who enter in a deictic communication about a target object with the perceiver and if the conditions laid out in ft. 3 are met, joint attention to the target will ensue.

It can, on some views at least, in principle turn out that what looks to be your public sofa is your private hallucination of the sofa. See the essays collected in Macpherson and Platchias (2013) for discussion.

See Briscoe and Grush (2020) for an overview of action-based theories of perception.

Having a conception of space in Evans’s (1982, p. 162/163) sense requires that one be able to locate one’s egocentre on a cognitive map, so as to be able to generate counterfactual hypotheses about what one would observe from locations one is not currently occupying. Though the onset of counterfactual thinking in children is debated, the earliest evidence for implicit reference to counterfactuals is at 2.5 years of age (Beck et al., 2011) and thus significantly later than the early stages of joint attention.

By “phenomenal present” I mean an experience that the perceiver would describe as occurring “now”, in the present. I say more about this notion in Section 4.

As already noted, this experiential view of joint attention is not the only possible one. I adopt it here without further discussion. For an extended discussion that includes the connection between joint attention, experience, and shared forms of practical and theoretical knowledge, see Seemann (2019).

The locution “which object” is imprecise. For present purposes, the object in question is the thing at the location identified by the participants in an episode of joint attention through social triangulation. For a treatment of the question how this definition deals with distinct objects occupying the same location and distinct objects overlapping at one location, see Seemann (2019, ch. 5).

See Avramides (2001) for an overview.

One possibility is that infants can directly perceive others as minded in social interaction (e.g., Gallagher, 2008). As a reviewer of this paper pointed out, it is of course also possible that full-fledged, adult joint attention is phenomenally and cognitively quite different from the early triadic interactions that one-year olds begin to engage in. Discussion is beyond the scope of this paper.

See Seemann (2019), ch. 11, for a discussion of the empirical findings that support the hypothesis of social space.

I am not suggesting that this account exhausts the phenomenology of joint attention. One important family of views suggests that it is the sharing, or attunement, of feelings or emotions between perceivers that distinguish the experience of joint attention from other forms of object perception (e.g., Hobson & Hobson, 2005; Seemann, 2011a; Trevarthen, 1980). The current proposal does not deny the relevance of intersubjectivity for a complete account of the phenomenology of joint attention. I am concerned here only with spatial awareness in joint attention, since it is that aspect of the experience of joint perceivers that can help explain the public character of the objects of shared attention.

See Schwenkler (2014) for an argument to the contrary.

References

Avramides, A. (2001). Other minds. Routledge.

Beck, S., Riggs, K., & Burns, P. (2011). Multiple developments in counterfactual thinking. In C. Hoerl, T. McCormack, & S. Beck (Eds.), Understanding counterfactuals, understanding causation: Issues in philosophy and psychology. Oxford University Press.

Briscoe, R. (2008). Vision, action, and make-perceive. Mind & Language, 23(4), 457–497.

Briscoe, R., & Grush, R. (2020). Action-based Theories of Perception. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/action-perception. Accessed 8 July 2022.

Campbell, J. (1994). Past, space, and self. MIT Press.

Campbell, J. (2002). Reference and consciousness. Oxford University Press.

Campbell, J. (2011). An object-dependent perspective on joint attention. In A. Seemann (Ed.), Joint attention: new developments in psychology, philosophy of mind, and social neuroscience (pp. 415-430ß). MIT Press.

Carrasco, L. (2011). Visual attention: The past 25 years. Vision Research, 51, 1484–1525.

De Vignemont, F. (2018). Peripersonal perception in action. Synthese, 198, 4027–4044.

De Vignemont, F. (2021). A minimal sense of here-ness. The Journal of Philosophy, 118(4), 169–187.

Eilan, N., Hoerl, C., McCormack, T., & Roessler, J. (Eds.). (2005). Joint attention: Communication and other minds. Oxford University Press.

Evans, G. (1982). The varieties of reference. Oxford University Press.

Gallagher, S. (2008). Direct perception in the intersubjective context. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 535–543.

Gallagher, S., Martinez, S., & Gastelum, M. (2017). Action-space and time: Towards an enactive hermeneutics. In B. Janz (Ed.), Place, space and hermeneutics (pp. 83–96). Springer International Publishing.

Grush, R. (2001). Self, world and space: The meaning and mechanisms of ego- and allocentric spatial representation. Brain and Mind, 1, 59–92.

Grush, R. (2004). The emulation theory of representation” motor control, imagery, and perception. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 377–442.

Grush, R. (2007). Skill theory v2.0: Dispositions, emulation, and spatial perception. Synthese, 159, 389–416.

Hobson, P., & Hobson, J. (2005). What puts the jointness into joint attention? In N. Eilan, C. Hoerl, T. McCormack, & J. Roessler (Eds.), Joint attention: Communication and other minds (pp. 185–204). Oxford University Press.

Kelly, S. D. (2004). Seeing things in Merleau-Ponty. In T. Carman & B. N. Hansen (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Merleau-Ponty (pp. 74–110). Cambridge University Press.

Macpherson, F., & Platchias, D. (2013). Hallucination: Philosophy and psychology. MIT Press.

Matthews, W., & Meck, W. (2016). Temporal cognition: Connecting subjective time to perception, attention, and memory. Psychological Bulletin, 142(8), 865–907.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1963). The structure of behaviour. Beacon Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945/2002). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge.

Mundy, P., Block, J., Delgado, C., Pomares, Y., Vaughan Van Hecke, A., & Parlade, M. V. (2007). Individual differences and the development of joint attention in infancy. Child Development, 78(3), 938–954.

Noe, A. (2004). Action in perception. MIT Press.

Noe, A. (2005). Real presence. Philosophical Topics, 33(1), 235–264.

Racine, T. (2011). Getting beyond rich and lean views of joint attention. In A. Seemann (Ed.), Joint attention: New developments in psychology, philosophy of mind, and social neuroscience (pp. 21–42). MIT Press.

Rizzolatti, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., & Gallese, V. (1997). The space around us. Science, 277, 190–191.

Schellenberg, S. (2007). Action and self-location in perception. Mind, 116(463), 603–632.

Schwenkler, J. (2014). Vision, self-location, and the phenomenology of the ‘Point of View.’ NOUS, 48(1), 137–155.

Seemann, A. (2011a). Joint attention: Toward a relational account. In A. Seemann (Ed.), Joint attention: New developments in psychology, philosophy of mind, and social neuroscience (pp. 183–202). MIT Press.

Seemann, A. (Ed.). (2011b). Joint attention: New developments in psychology, philosophy of mind, and social neuroscience. MIT Press.

Seemann, A. (2019). The shared world: Perceptual common knowledge, demonstrative communication, and social space. MIT Press.

Trevarthen, C. (1980). The foundations of intersubjectivity: Development of Interpersonal and Cooperative understanding in infants. In D. Olson (Ed.), The social foundations of language and thought: Essays in honor of J.S. Bruner (pp. 316–342). Norton.

Zahavi, D. (2011). The experiential self: Objections and clarifications. In M. Siderits, A. Thompson, & D. Zahavi (Eds.), Self, no self? Perspectives from analytical, phenomenological, and Indian traditions (pp. 56–79). Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my reviewers and the editors of this special issue for their extremely constructive and helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

There is no conflict of interests that would need to be declared.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seemann, A. The public character of visual objects: shape perception, joint attention, and standpoint transcendence. Phenom Cogn Sci (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-022-09842-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-022-09842-6