Abstract

Research has shown that people can respond both self-defensively and pro-socially when they experience shame. We address this paradox by differentiating among specific appraisals (of specific self-defect and concern for condemnation) and feelings (of shame, inferiority, and rejection) often reported as part of shame. In two Experiments (Study 1: N = 85; Study 2: N = 112), manipulations that put participants’ social-image at risk increased their appraisal of concern for condemnation. In Study 2, a manipulation of moral failure increased participants’ appraisal that they suffered a specific self-defect. In both studies, mediation analyses showed that effects of the social-image at risk manipulation on self-defensive motivation were explained by appraisal of concern for condemnation and felt rejection. In contrast, the effect of the moral failure manipulation on pro-social motivation in Study 2 was explained by appraisal of a specific self-defect and felt shame. Thus, distinguishing among the appraisals and feelings tied to shame enabled clearer prediction of pro-social and self-defensive responses to moral failure with and without risk to social-image.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Reliabilities were calculated using the pooled data with items centered around their mean within each sample, as described subsequently.

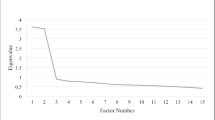

Although the small sample sizes speak against a CFA, we tested our measurement model separately in the data from each study. In both samples, the model fit was acceptable (Study 1 χ 2 [55] = 130.42, p < .001, CFI = .901, SRMR = .086; Study 2 χ 2 [55] = 127.43, p < .001, CFI = .925, SRMR = .061) and all items loaded substantially (standardized λ’s > .50) and significantly (p < .001) on their predicted factors. To confirm whether it was appropriate to pool the data across the two samples, we tested for metric invariance within our measurement model by comparing two multi-group models so that we could validly compare correlational patterns across samples (Chen 2008). A first model estimating factor loadings and intercepts freely within each sample showed acceptable fit, χ 2 (110) = 257.85, p < .001, CFI = .914, SRMR = .073. We then computed a second model, in which we constrained the factor loadings to be equal across the two samples. If the fit of the constrained model remains acceptable, it can be preferred to the unconstrained model because it is more parsimonious, and the hypothesis of invariance can be considered tenable (e.g., Little et al. 2007). The constrained model showed an acceptable fit to the data, χ 2 (118) = 290.03, p < .001, CFI = .900, SRMR = .091, indicating that the assumption of metric invariance across the two samples was tenable.

In our original study design, a further forty-three participants were assigned to a moral failure with damage to social-image condition. The instructions here were identical to those of the moral failure with risk to social-image condition, except that participants were told that their story had been selected to be read to the group and that they would be identified. Thus, social-image was clearly going to be damaged in this condition, rather than risked. This strong threat appeared to lead to reactance, whereby participants gave very low average ratings on all of our measures. Moreover, six participants (i.e. 14 % of this condition) left the study before completing the substantive measures. Given our uncertainty about the validity of participants’ responses, as well as the threat to internal validity posed by the high drop-out rate, we decided not to analyze the moral failure with damage to social-image control condition. Note that this condition does not relate directly to our theoretical predictions, which focus on how people respond to risks to their social image, rather than certain damage.

Further analysis showed that felt shame was a unique predictor of the pro-social motivation to make restitution even when controlling for felt guilt. We conducted a hierarchical Multiple Regression analysis predicting restitution, rather than avoidance. To ensure that the pro-social effects of felt shame were not in fact attributable to guilt (cf. Tangney and Dearing 2002), we additionally included a measure of felt guilt (α = .80: “I feel guilty because of this”, “I feel responsible because of this”, “I feel guilty when I think about what I did towards my family member”). In Step 1, we controlled for gender and risk to social-image. In Step 2, felt shame significantly predicted restitution (β = .47, p < .001) and explained a substantial amount of additional variance, ΔF (1, 78) = 22.09, p < .001, ΔR 2 = 21.5 %. In Step 3, felt guilt did not explain significant additional variance, ΔF (1, 77) = 1.83, p = .180, ΔR 2 = 1.8 %, and felt shame remained a significant predictor of restitution (β = .35, p = .009), whereas felt guilt was not (β = .18, p = .180). In Step 4, felt rejection, felt inferiority, and appraisals of individual defect and concern for condemnation did not explain significant additional variance, ΔF (4, 73) = 1.81, p = .135, ΔR 2 = 6.7 %, whereas felt shame remained a significant predictor of restitution (β = .28, p = .044).

We checked the multi-collinearity diagnostics in our regression analyses. None of the Variance Inflation Factors was above 5, and none of the tolerances was below .2.

References

Ahmed, E., Harris, N., Braithwaite, J., & Braithwaite, V. (2001). Shame management through reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Allpress, J. A., Barlow, F. K., Brown, R., & Louis, W. R. (2010). Atoning for colonial injustices: Group-based shame and guilt motivate support for reparation. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 4, 75–88.

Allpress, J. A., Brown, R., Giner-Sorolla, R., Deonna, J. A., & Teroni, F. (2014). Two faces of group-based shame moral shame and image shame differentially predict positive and negative orientations to ingroup wrongdoing. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40, 1270–1284. doi:10.1177/0146167214540724.

Berndsen, M., & Gausel, N. (2015). When majority members exclude ethnic minorities: The impact of shame on the desire to object to immoral acts. European Journal of Social Psychology,. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2127.

Berndsen, M., & McGarty, C. (2012). Perspective taking and opinions about forms of reparation for victims of historical harm. Personality and Social Psychological Bulletin,. doi:10.1177/0146167212450322.

Boomsma, A. (1982). The robustness of LISREL against small sample sizes in factor analysis models. In K. G. Jöreskog & H. Wold (Eds.), Systems under indirect observation: Causality, structure, prediction (Part 1 (pp. 149–173). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: vol 1. Attachment.. New York: Basic Books.

Chen, F. F. (2008). What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks? The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1005–1018. doi:10.1037/a0013193.

de Hooge, I. (2014). The general sociometer shame: Positive interpersonal consequences of an ugly emotion. In K. G. Lockhart (Ed.), Psychology of shame: New research (pp. 95–109). Hauppauge: Nova Publishers.

de Hooge, I. E., Breugelmans, S. M., & Zeelenberg, M. (2008). Not so ugly after all: When shame acts as a commitment device. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 933–943. doi:10.1037/a0011991.

de Hooge, I. E., Zeelenberg, M., & Breugelmans, S. M. (2010). Restore and protect motivations following shame. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 111–127. doi:10.1080/02699930802584466.

Ferguson, T. J. (2005). Mapping shame and its functions in relationships. Child Maltreatment, 10, 377–386. doi:10.1177/1077559505281430.

Ferguson, T. J., Brugman, D., White, J. E., & Eyre, H. L. (2007). Shame and guilt as morally warranted experiences. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 330–348). New York: Guilford Press.

Fischer, R., & Fontaine, J. (2011). Methods for investigating structural equivalence. In D. Matsumoto & F. J. R. van de Vijver (Eds.), Cross-cultural research methods in psychology (pp. 179–215). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Frijda, N. H., Kuipers, P., & ter Schure, E. (1989). Relations among emotion, appraisal, and emotional action readiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 212–228. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.2.212.

Gausel, N. (2006). Gravity keeps my head down, or is it maybe shame? The effects of Essence and Reputation in Shame on defensive responses, anger, blame and pro-social emotions. Unpublished Master Thesis, University of Sussex.

Gausel, N. (2013). Self-reform or self-defense? Understanding how people cope with their moral failures by understanding how they appraise and feel about their moral failures. In M. Moshe & N. Corbu (Eds.), Walk of shame (pp. 191–208). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Publishers.

Gausel, N. (2014a). What Does “I Feel Ashamed” Mean? Avoiding the pitfall of definition by understanding subjective emotion language. In K. G. Lockhart (Ed.), Psychology of Shame: New research (pp. 157–166). Hauppauge: Nova Publishers.

Gausel, N. (2014b). It’s not our fault! Explaining why families might blame the school for failure to complete a high-school education. Social Psychology of Education, 17, 609–616. doi:10.1007/s11218-014-9267-5.

Gausel, N., & Brown, R. (2012). Shame and guilt—do they really differ in their focus of evaluation? Wanting to change the self and behaviour in response to ingroup immorality. The Journal of Social Psychology, 152, 1–20. doi:10.1080/00224545.2012.657265.

Gausel, N., & Leach, C. W. (2011). Concern for self-image and social-image in the management of moral failure: Rethinking shame. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 468–478. doi:10.1002/ejsp.803.

Gausel, N., Leach, C. W., Vignoles, V. L., & Brown, R. (2012). Defend or repair? Explaining responses to in-group moral failure by disentangling feelings of shame, inferiority and rejection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 941–960. doi:10.1037/a0027233.

Gausel, N., & Salthe, G. (2014). Assessing natural language: Measuring emotion-words within a sentence or without a sentence? Review of European Studies, 6, 127–132. doi:10.5539/res.v6n1p127.

Gerber, J., & Wheeler, L. (2009). On being rejected. A meta-analysis of experimental research on rejection. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 468–488. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01158.x.

Gilbert, P., & Andrews, B. (Eds.). (1998). Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 78–98). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118.

Imhoff, R., Bilewicz, M., & Erb, H.-P. (2012). Collective regret versus collective guilt: Different emotional reactions to historical atrocities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 729–742. doi:10.1002/ejsp.1886.

Iyer, A., Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2007). Why individuals protest the perceived transgressions of their country: The role of anger, shame, and guilt. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. doi:10.1177/0146167206297402.

Keltner, D., & Harker, L. A. (1998). The forms and functions of the nonverbal signal of shame. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 78–98). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaption. New York: Oxford University Press.

Leach, C. W. (2010). The person in political emotion. Journal of Personality, 78, 1827–1859. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00671.x.

Leach, C. W., Bilali, R., & Pagliaro, S. (2014). Groups and morality. In J. Simpson & J. Dovidio (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 2: Interpersonal relationships and group processes. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: The importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 234–249. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234.

Leach, C. W., & Spears, R. (2008). “A vengefulness of the impotent”: The pain of in-group inferiority and schadenfreude toward successful out-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1383–1396. doi:10.1037/a0012629.

Leary, R. M. (2007). Motivational and emotional aspects of the self. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 317–344. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085658.

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International Universities Press.

Lewis, M. (1992). Shame, the exposed self. New York: Free Press.

Lickel, B., Kushlev, K., Savalei, V., Matta, S., & Schmader, T. (2014). Shame and motivation to change the self. Emotion, 14, 1049–1061. doi:10.1037/a0038235.

Lickel, B., Schmader, T., Curtis, M., Scarnier, M., & Ames, D. R. (2005). Vicarious shame and guilt. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 8, 145–157. doi:10.1177/1368430205051064.

Little, T. D., Card, N. A., Slegers, D. W., & Ledford, E. C. (2007). Representing contextual effects in multiple-group MACS models. In T. D. Little, N. A. Bovaird, & J. A. Card (Eds.), Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies (pp. 121–147). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fairchild, A. J., & Fritz, M. S. (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralising Hu & Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modelling, 11, 320–341. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). MPLUS user’s guide, 6th Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Niedenthal, P. M., Tangney, J., & Gavanski, I. (1994). “If only I weren’t” versus “If only I hadn’t”: Discriminating shame and guilt in counterfactual thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 585–595. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.585.

Otten, M., & Jonas, K. J. (2014). Humiliation as an intense emotional experience: Evidence from the electro-encephalogram. Social Neuroscience, 9, 23–35. doi:10.1080/17470919.2013.855660.

Retzinger, S., & Scheff, T. J. (2000). Emotion, alienation, and narratives: Resolving intractable conflict. Mediation Quarterly, 18, 71–85. doi:10.1002/crq.3890180107.

Robinson, M. D., & Clore, G. L. (2001). Simulation, scenarios, and emotional appraisal: Testing the convergence of real and imagined reactions to emotional stimuli. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 1520–1532. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.934.

Rodriguez Mosquera, P. M., Fischer, A. H., Manstead, A. S. R., & Zaalberg, R. (2008). Attack, disapproval, or withdrawal? The role of honour in anger and shame responses to being insulted. Cognition and Emotion, 22, 147–1498. doi:10.1080/02699930701822272.

Rodriguez Mosquera, P. M., Manstead, A. S. R., & Fischer, A. H. (2002). The role of honour concerns in emotional reactions to offences. Cognition and Emotion, 16, 143–163. doi:10.1080/02699930143000167.

Roseman, I. J., Wiest, C., & Swartz, T. S. (1994). Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 206–221. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.2.206.

Scheff, T. J. (2000). Shame and the social bond: A sociological theory. Sociological Theory, 18, 84–99. doi:10.1111/0735-2751.00089.

Scherer, K. R., Schorr, A., & Johnstone, T. (2001). Appraisal processes in emotion: Theory, methods, research. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schmader, T., & Lickel, B. (2006). The approach and avoidance function of guilt and shame emotions: Comparing reactions to self-caused and other-caused wrongdoing. Motivation and Emotion, 30, 43–56. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9006-0.

Shaver, P., Schwartz, J., Kirson, D., & O’Connor, C. (1987). Emotion knowledge: Further exploration of a prototype approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1061–1086. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.6.1061.

Shepherd, L., Spears, R., & Manstead, A. S. (2013). ‘This will bring shame on our nation’: The role of anticipated group-based emotions on collective action. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 42–57. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.011.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi:10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422.

Smith, R. H., Webster, J. M., Parrot, W. G., & Eyre, H. L. (2002). The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 138–159. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.138.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford.

Tangney, J. P., & Fischer, K. W. (1995). The self-conscious emotions: Shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride. New York: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Miller, S. R., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1256–1269. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Martinez, A. G. (2014). Two faces of shame: The roles of shame and guilt in predicting recidivism. Psychological Science,. doi:10.1177/0956797613508790.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behaviour. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2004). Putting the self into self-conscious emotions: A theoretical model. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 103–125. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli1502_01.

Tracy, J. L., & Robins, R. W. (2006). Appraisal antecedents of shame and guilt: Support for a theoretical model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32, 1339–1351. doi:10.1177/0146167206290212.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the three coders of Study 1—Kristin Enge, Cristine Rekdal and Bodil Skåland. We would also like to thank David A. Kenny and the students and faculty at the International Graduate College, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany, for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Nicolay Gausel, Vivian L. Vignoles and Colin Wayne Leach have contributed equally to this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gausel, N., Vignoles, V.L. & Leach, C.W. Resolving the paradox of shame: Differentiating among specific appraisal-feeling combinations explains pro-social and self-defensive motivation. Motiv Emot 40, 118–139 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9513-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9513-y